Availableonlineatwww.sciencedirect.com

ScienceDirect

HOSTED BY

EconomiA17(2016)43–55

Taxation,

credit

constraints

and

the

informal

economy

夽

Julia

P.

Araujo,

Mauro

Rodrigues

∗DepartmentofEconomics,UniversityofSãoPaulo,Av.Prof.LucianoGualberto908,SãoPaulo,SP05508-010,Brazil

Received1March2016;accepted17March2016 Availableonline5April2016

Abstract

Thispaper extends Evansand Jovanovic (1989)’s entrepreneurship modelto incorporate the informal sector. Specifically, entrepreneurscanoperateeitherintheformalsector–inwhichtheyhavelimitedaccesstocreditmarketsandmustpaytaxes –orintheinformalsector–inwhichtheycanavoidpayingtaxes,buthavenoaccesstocreditmarkets.Inaddition,technology intheinformalsectorisbothlessproductiveandmorelaborintensivethanthatintheformalsector.Wecalibratethemodeltothe Brazilianeconomy,andevaluatetheimpactofcreditfrictionsandtaxationonoccupationalchoices,aggregateoutputandinequality. Removingalldistortionscanimproveaggregateefficiencyconsiderably,largelybecausethisinducesentrepreneurstoswitchto theformalsector,wherethetechnologyissuperior.Mostofthiseffectcomesfromremovingcreditmarketfrictions,buttaxeson formalbusinessesarealsoimportant.Theeliminationofdistortionscanalsoreduceincomeinequalitysubstantially.

©2016NationalAssociationofPostgraduateCentersinEconomics,ANPEC.ProductionandhostingbyElsevierB.V.Allrights reserved.

JELclassification: E26;L26;O17

Keywords: Informalsector;Creditfrictions;Taxation;Entrepreneurship

Resumo

Estetrabalho incorporaosetor informal aomodelo deempreendedorismo deEvanse Jovanovic(1989). Especificamente, empreendedorespodemoperarnosetorformal-comacessolimitadoaomercadodecréditoesujeitosacobranc¸adeimpostos -ounosetorinformal-evitandoatributac¸ão,massemacessoacrédito.Adicionalmente,atecnologianosetorinformalémenos produtivaemaisintensivaemtrabalho.Omodeloécalibradocombaseemdadosdaeconomiabrasileira.Avaliam-seosefeitos detributosederestric¸õesnomercadodecréditosobreasescolhasocupacionais,produc¸ãoagregadaedesigualdade.Aremoc¸ão detodasasdistorc¸õesmelhoraaeficiênciaagregadademaneiraconsiderável,principalmenteporcontadamigrac¸ãodeagentes paraoempreendedorismoformal,queoperacomumatecnologiasuperior.Arestric¸ãodecréditopossuiomaiorefeito,masos

夽 WethankGabrielMadeira,EnlinsonMattosandVladimirTelesforhelpfulcommentsandsuggestions.FinancialsupportfromFAPESPis

gratefullyacknowledged.

∗Correspondingauthor.Tel.:+551130916069.

E-mailaddress:mrodrigues@usp.br(M.Rodrigues).

PeerreviewunderresponsibilityofNationalAssociationofPostgraduateCentersinEconomics,ANPEC.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.econ.2016.03.003

impostossobreempresasformaistambémtêmpapelimportante.Aeliminac¸ãodedistorc¸õesaindapermitereduzirsubstancialmente adesigualdadederendanomodelo.

©2016NationalAssociationofPostgraduateCentersinEconomics,ANPEC.ProductionandhostingbyElsevierB.V.Allrights reserved.

Palavras-chave:Setorinformal;Restric¸õesdecrédito;Taxac¸ão;Empreendedorismo

1. Introduction

Largeinformal sectorsareadistinctivefeature ofdevelopingeconomies.1Firmsoperateinformallyasameans ofavoidingregulationsandtaxation.However,therearecoststothisaction,suchaslackofaccesstoformalcredit marketsandtothelegalsystem.Moreover,thereisevidencesuggestingthatfirmsintheinformalsectorarealsoless productive(LaPortaandShleifer,2008).

Inthepresentpaper,weexploresomeelementsofthistradeoffbyembeddingastandardentrepreneurshipmodel

(EvansandJovanovic,1989)withaninformal sector.Specifically, thereare twosectors:theformalsectorandthe

informalsector.Intheformalsector,entrepreneurshaveimperfectaccesstocreditmarketsandhavetopaytaxes,while intheinformalsectortheycanevadethepaymentoftaxesbutarebarredfromcreditmarkets.Furthermore,technology islessefficientandmorelaborintensiveintheinformalsector.

Agentsareheterogeneousintheirentrepreneurialtalentandwealth.Basedonthis,theydecidebetweenthree occu-pations:wageworking,entrepreneurshipintheformalsectorandentrepreneurshipintheinformalsector.Differently fromEvansandJovanovic,wealsoallowwagestobeendogenous,whichgivesrisetonontrivialeffectsonincome distribution.2WecalibratethemodeltoapproximatefeaturesoftheBrazilianeconomy,andevaluatetheeffects of taxationandcreditconstraintsonefficiency(aggregateoutput),formalizationandinequality.

Takentogether,the frictionsincluded inthe modelare abletogeneratesubstantial inefficiency.Particularly,in ourbasiccalibration,aggregateoutputis37percentbelowthatofanundistortedeconomy.Mostofthisgapcomes fromcreditconstraintsonformalentrepreneurs:removingthisfriction(holdingtaxesconstant)reducesthelevelof inefficiencytoabout10percent.Taxationonformalbusinessesalsohasanimportantimpactonoutput:inefficiencyis morethanhalvedwhenweequalsuchtaxestozero.Theseeffectscomelargelyfromthemigrationofentrepreneurs fromtheinformaltotheformalsector,whereproductivityishigher.

Wealsoevaluatehowtaxesonlaborincome(uniformacrosssectors)affecttotaloutput.Reducingsuchtaxescan actuallymaketheeconomylessefficient(althoughtheeffectissmallinmagnitude),sinceitlowersgrosswages,thus makingtheinformalsector(whichislaborintensive)moreattractive.

Removingallfrictionsalsoreducesincomeinequalityinthemodel.Bothtaxratesarethemaindriverbehindthis effect.Removingborrowingconstraintsalsocontributestolowerinequality,butthemagnitudeoftheeffectismuch smallerthanthatofeliminatingtaxrates.

Ourworkisrelatedtoalargeliteraturethatevaluatestheeffectofcreditmarketfrictionsonentrepreneurship(see forinstanceEvansandJovanovic,1989;BlanchflowerandOswald,1998;PaulsonandTownsend,2004;Buera,2008). Ourmaincontributionistoaddtwodifferentsectors(formalandinformal)totheclassicmodelofEvansandJovanovic. Thisallowsustoanalyzenotonlytheeffectofcreditconstraints,butalsooftaxation.Moreover,theseeffectscanbe largerthaninamodelwithasinglesector,sincechangesinparametersinduceindividualstoswitchsectorsthathave differenttechnologies.

Thefocusonefficiencyismotivatedbytheliteratureonmisallocation(HsiehandKlenow,2007;Restucciaand

Rogerson,2008),especiallyJeongandTownsend(2007)andBanerjeeandMoll(2010),whichanalyzetheeffectof

creditmarketfrictionsonaggregateproductivity.Regardingtheeffectoninequality,ourworkisparticularlyrelated

toCagettiandDeNardi(2006).Oncemore,consideringtheinformalsectorcanamplifytheeffectofsuchfrictions,

sincetheyinfluencethesector(andthereforetechnology)inwhichindividualschoosetooperate.Thepresentstudyis

1 See,forinstance,Schneider(2005,2012).

alsorelatedtopapersthatmodeltheinformalsector,suchasRauch(1991),AmaralandQuintin(2006),Antunesand

Cavalcanti(2007),D’ErasmoandMoscoso-Boedo(2012),DePaulaandScheinkman(2011)andOrdonez(2014).

Therestofthepaperisorganizedasfollows.Section2describesthemodel.Section3explainshowthemodelwas calibratedtotheBrazilianeconomy.Section4presentssimulationsregardingchangesincreditfrictionsandtaxation, andanalyzestheeffectsonefficiency,occupationalchoiceandinequality.Section5concludes.

2. Model

OurstartingpointisthemodelproposedbyEvansandJovanovic(1989).Specifically,thereisasetofindividuals, heterogeneousintheirwealthandentrepreneurialtalent.Eachofthemchooseseithertobeanentrepreneurorawage worker.Tobecomeanentrepreneur,theindividualmayneedtoborrowresources.Thepresenceofborrowingconstraints thenimpliesthatoccupationalchoicedependsnotonlyonentrepreneurialtalent,butalsoonwealth.

WeaddtoEvansandJovanovic(1989)byintroducingtwodifferentsectorsinwhichtheentrepreneurcanoperate:

theformalsectorandtheinformalsector.Intheformer,theentrepreneurmayborrowalimitedamountofresourcesto financeherbusinessbuthastopaytaxes,whereasintheinformalsectortheindividualcanevadethepaymentoftaxes, buthastorelyexclusivelyonherwealth(shehasnoaccesstocreditmarkets).Weconsiderasmallopeneconomy,so thattheinterestrateisexogenouslyfixed.Nonetheless,differentlyfromEvansandJovanovic(1989),wagesareset accordingtoamarketclearingcondition.

2.1. Technology

Thereisacontinuumofmass1ofindividuals,whichareheterogeneousintwodimensions:entrepreneurialtalent –θ∈[0,∞)–andwealth–z∈ [0,∞).Theyaredistributedinthepopulationaccordingtothepdff(θ,z).Outputis homogeneousandmaybeeitherproducedintheformalsectororintheinformalsector.Anentrepreneuroftalentθ

operatingintheformalsectorcombinescapital(Kf)andlabor(Lf)togenerateoutputusingthefollowingtechnology:

Yf =θ

KαfL1f−α

γ

whereγ ∈(0,1)isthespanofcontrolparameter,asinLucas(1978).Forthissameentrepreneur,productioninthe informalsectorisgivenby:

Yi =ψθ

KβiL1i−β

γ

whereKi andListandfortheamountsofcapitalandlaboremployedbytheentrepreneurinthissector,andψisa parameterthatdoesnotdependonθ.Weassume0<ψ<1andβ<α,thatis,productionintheinformalsectorisboth lessefficientandmorelaborintensive.3

2.2. Theformalsector

Ifapersondecidestobeanentrepreneurintheformalsector,shemayneedexternalfundstofinancehercapital. However,therearecreditconstraints:anagentcanborrowuptoamultipleofherwealth.Specifically,anindividual withwealth zis able toborrow atmost (λ−1)z,whereλ ∈[1, ∞) isa parameterthat measures how lax isthe borrowingconstraint.Theentrepreneurthenhasthisamountplusherownwealth–thatis,(λ−1)z+z=λz–available forinvestment.Thisimpliesthatthecapitalstockemployedbyherfirm(Kf)cannotexceedλz.

Netearningsofaformalentrepreneurwithwealthzandtalentθaregivenby:

πf(θ,z)= max Kf,Lf {(1−τf)θ(KαfL 1−α f ) γ −wLf −r(Kf −z)+T : 0≤Kf ≤λz}

whereτfisthetaxrateonoutput(ifproducedintheformalsector),wisthewagerate,r−1istherealinterestrate andTisalump-sumtransfer.Taxrevenuesaredistributeduniformlyacrossthepopulationinalump-sumfashion.In

otherwords,Tdependsneitherontheperson’scharacteristics,noronheroccupation.Iftheborrowingconstraintdoes notbind(unconstrainedentrepreneur),optimalityconditionsimplythat:

Kfu∗ = ⎡ ⎢ ⎢ ⎢ ⎣ γθ(1−τf) r α 1−(1−α)γ w 1−α (1−α)γ ⎤ ⎥ ⎥ ⎥ ⎦ 1/(1−γ) L∗fu = ⎡ ⎢ ⎢ ⎢ ⎣ γθ(1−τf) r α αγ w 1−α 1−αγ ⎤ ⎥ ⎥ ⎥ ⎦ 1/(1−γ)

whicharetheamountsofcapitalandlaborchosenbyanunconstrainedentrepreneur.Inthiscase,theindividualuses theefficientquantitiesofbothinputs,andherchoicedoesnotdependonwealth.Ontheotherhand,iftheentrepreneur isconstrained,wehavethat:

Kfc∗ =λz L∗fc = γθ(1−τf)(1−α)(λz)αγ w 1/(1−α(1−γ))

Therefore,iftheconstraintbinds,theentrepreneur’swealthaffectsthescaleofherenterprise.Theoptimalchoice ofinputsbyanentrepreneurintheformalsectorcanthenbeexpressedas:

Kf∗ = λz, ifK∗fu>λz Kfu∗ , otherwise L∗f = L∗fc, ifKfu∗ >λz L∗fu otherwise

2.3. Theinformalsector

Theentrepreneurintheinformalsectorhasaproblemanalogoustothatintheformalsectorwithtwokeydifferences: (i)shecanevadethepaymentoftaxes(τf=0),and(ii)shehasnoaccesstocreditmarkets,havingonlyherownwealth touseascapital(λ=1).Netearningsarethusgivenby:

πi(θ,z)=max Ki,Li

{θψ(KiβLi1−β)γ−wLi−r(Ki−z)+T : 0≤Ki ≤z}

Theoptimalchoiceofinputsbyanunconstrainedentrepreneuristhen:

Kiu∗ = ⎡ ⎢ ⎢ ⎢ ⎣ γψθ r β 1−(1−β)γ w 1−β (1−β)γ ⎤ ⎥ ⎥ ⎥ ⎦ 1/(1−γ) L∗iu= ⎡ ⎢ ⎢ ⎢ ⎣ γψθ r β βγ w 1−β 1−βγ ⎤ ⎥ ⎥ ⎥ ⎦ 1/(1−γ)

whileaconstrainedentrepreneurchooses: K∗ic=z L∗ic= γψθ(1−α)zβγ w 1/(1−β(1−γ))

Theoptimaldecisionofanentrepreneurintheinformalsectoristhensummarizedby:

K∗i = z, ifKiu∗ >z K∗iu, otherwise L∗i = L∗ic, ifK∗iu>z L∗iu, otherwise 2.4. Wageworker

Apersonwhodecidestobeawageworkerreceivesthewage(netoftaxes),thelump-sumtransferandintereston herwealth.Eachwageworkersuppliesoneunitoftimeinelastically.Inotherwords,laborincomedoesnotdepend onentrepreneurialtalent.FollowingAmaralandQuintin(2006),wesupposenosegmentationinthelabormarket,so thatwagesareequalizedacrosssectors.Netearningsofawageworkerwithwealthzarethen:

πw(z)=(1−τn)w+rz+T whereτnisthetaxrateonlaborincome.4 2.5. Equilibrium

The decisionof each agent is static. Giventalent andwealth,she chooses the occupationwhichgives herthe highestnetincome:wageworker,entrepreneurintheformalsector,orentrepreneurintheinformalsector.Therefore,

π(θ,z)=max{πf(θ,z),πi(θ,z),πw(z)}arethenetearningsofanindividualwithwealthzandtalentθ.Thefraction ofagentsoptingforeachoccupationj ∈ {f,i,w}is:

Oj=

1{π(θ,z)=πj(θ,z)}f(θ,z)dθdz

wherethesubscriptsf,iandwstandforentrepreneurintheformalsector,entrepreneurininformalsectorandwage worker,respectively.Theequilibriumwageissuchthat:

Of +Oi+Ow=1

andthatthesupplyoflaborfromwageworkers(left-handsideoftheequationbelow)isequaltothedemandforlabor fromformalandinformalentrepreneurs(right-handside):

Ow=

1{π(θ,z)=πf(θ,z)}L∗ff(θ,z)dθdz+

1{π(θ,z)=πi(θ,z)}L∗if(θ,z)dθdz Furthermore,sincetaxrevenuesaretransferredbackuniformlytotheagents,wehavethat:

T = 1{π(θ,z)=πf(θ,z)}τfθ K∗fαL∗f1−α γ f(θ,z)dθdz+Owτnw

wherethetermsontheright-handsidearetheproceedsfromtaxationonformalentrepreneursandonlaborincome, respectively.

4 Inthemodelτ

fdrivesthewedgeacrosssectors.Weassumethatthetaxonlaborincomeisuniformacrosssectors(thatis,ithastobepaid independentlyofthesectortheworkerchooses),sothatτndoesnotcapturethiswedgeaswell.

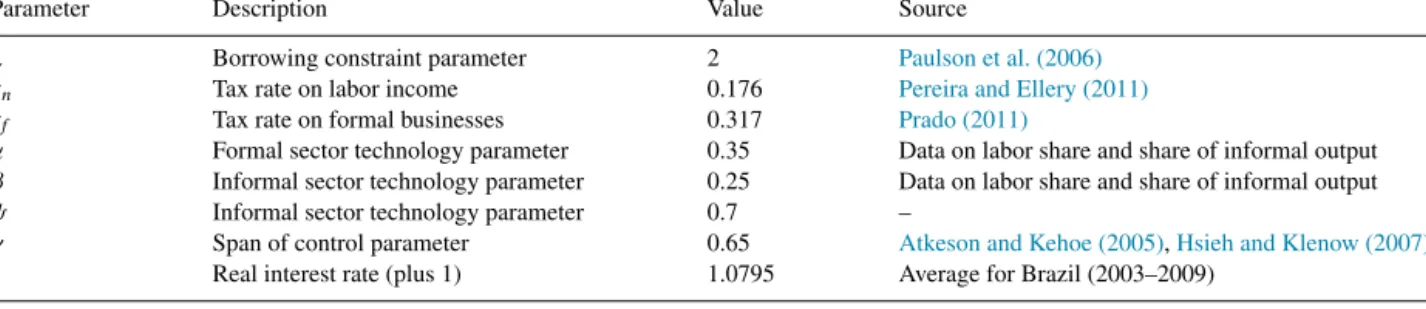

Table1 Parametervalues.

Parameter Description Value Source

λ Borrowingconstraintparameter 2 Paulsonetal.(2006) τn Taxrateonlaborincome 0.176 PereiraandEllery(2011) τf Taxrateonformalbusinesses 0.317 Prado(2011)

α Formalsectortechnologyparameter 0.35 Dataonlaborshareandshareofinformaloutput β Informalsectortechnologyparameter 0.25 Dataonlaborshareandshareofinformaloutput ψ Informalsectortechnologyparameter 0.7 –

γ Spanofcontrolparameter 0.65 AtkesonandKehoe(2005),HsiehandKlenow(2007) r Realinterestrate(plus1) 1.0795 AverageforBrazil(2003–2009)

3. Calibration

Our mainobjective is tounderstand the effects of taxation andborrowing constraintson occupational choice, aggregateefficiencyandinequality,inanenvironmentinwhichasignificantfraction ofoutput isproducedinthe informalsector.Todoso,wecalibratethemodeltoapproximatesomefeaturesoftheBrazilianeconomy.Alongwith valuesforthemodel’sparameters,weneedfunctionalformsforthedistributionsofwealthandentrepreneurialtalent.

3.1. Parametervalues

Table1presentsourbaselinecalibrationforthemodel’sparameters.Someofthesevalueswerechoseninconformity

withtheliterature,whileothersweresettoreplicatefeaturesoftheBrazilianeconomy.Specifically,wechooseλ=2 forourborrowingconstraintparameter,whichmeansthattheamountborrowedbyaformalentrepreneurcannotbe largerthanthevalueofherownwealth.ThisvalueisinlinewithPaulsonetal.(2006)’sstudyontheThaieconomy.

Regardingthespanofcontrolparameter,wechooseγ=0.65,whichistheaverageofthevaluesusedbyHsiehand

Klenow(2007)andAtkesonandKehoe(2005)–respectively,0.5and0.8.Further,wesetα=0.35andβ=0.25.Inthe

model,thelaborshareisgivenby:5

γ(1−α) 1−Yi Y +γ(1−β)Yi Y

whereYi/Yistheshareofinformaloutputontotaloutput,whichisestimatedtobe0.39fortheBrazilianeconomy

(Schneider,2012).Giventhis,ourchoiceofparametersyieldsalaborshareof44.8%.AccordingBrazil’s National

Accounts,compensationofemployeesis41%ofGDP(averagefortheperiod2003–2009).6

Theparameterψissetat0.7.Thisvalueguaranteesthatbothsectors areactiveinourbaselinecalibration.Tax ratesonwagesandformaloutputweresetatτn=0.176andτf=0.317.ThesevalueswereestimatedfortheBrazilian economyrespectivelybyPereira andEllery(2011)andPrado(2011).Finally,basedonthe averageBrazilianreal interestratebetween2003and2009,wesetr=1.0795.7

5 Thelaborshareintheformalsectorisγ(1−α),thatis,theexponentonlaborintheproductionfunctionofthatsector.Analogously,γ(1−β)is thelaborshareintheinformalsector.Theeconomywidelaborshareistheweightedaverageofsectorallaborshares,wheretheweightsaregiven bytheshareofeachsectorintotaloutputY.

6 Laborshareestimatesareusuallyadjustedtoincludeafractionofself-employmentincome,especiallyfordevelopingcountries(seeGollin, 2002).Herewedonotmakesuchadjustment,sinceweviewself-employmentincomeasentreprenuerialincome.

7 Tocalculatetheannualrealinterestrate,weusetheshort-termnominalinterestrate(theSELICrate,whichistargetedbyBrazilianCentral Bankformonetarypolicypurposes)inannualterms,minustheannualrateofCPIinflation(IPCA).

Fig.1.Occupationalchoices(withouttheinformalsector). 3.1.1. Distributionofwealthandentrepreneurialtalent

Wesupposethatwealthandtalentareindependentlydistributed.Regardingwealth,wechoosealog-normal dis-tribution,i.e.,logz∼N(μz,σz2).ThestandarddeviationσzcanbemappedintotheGiniindexthroughthefollowing formula:

Gini=2(σz/

√

2)−1

where(·)isthecdfofthenormaldistribution.ToourknowledgetherearenowealthsurveysinBrazil,whichcould providedirectestimatesofthewealthGiniindex.Daviesetal.(2011)usedatafromcountrieswithwealthsurveysto projectthewealthGinicoefficientofothercountries.ForBrazil,theirestimateis0.784.Weusethisvaluetocalibrate

σz=1.75.

Entrepreneurialtalentisanunobservablevariable.Ourstrategyistoassumeauniformdistribution–θ∼U(0,A)– andcalibratetheparameterA,alongwiththeparameterμzfromthewealthdistribution,toapproximatetwostatistics

Table2

Occupationalchoices(%).

Wageworkers Formalentrepreneurs Informalentrepreneurs

All Constrained Unconstrained All Constrained Unconstrained

Shareinpopulation 65.6 17.9 14.3 3.6 16.5 8.5 8.0

Meantalent 5.9 14.6 14.8 14.3 14.3 15.8 14.0

Meanwealth 5.4 1.8 0.9 2.3 12.5 0.7 15.7

Shareinoutput 59.0 53.4 5.6 41.0 17.0 24.0

Shareinemployment 48.3 45.1 3.2 51.7 16.8 34.9

fromtheBrazilianeconomy:(i)theshareofinformaloutputintotalGDP–39%accordingtoSchneider(2012);and (ii)theshareofwageworkersintotalemployment–63.8%accordingtheBrazilianHouseholdSurvey(averagefor the2003–2009period).8Specifically,wesetμz=0.2andA=17.6,whichproduceashareofinformaloutputintotal GDPof41%andashareofwageworkersinthepopulationof65.6%inthemodel.

4. Simulations

Oursimulationsarebasedonarandomdrawof100,000individualsfromthe distributionsoftalent andwealth describedabove.Beforeturningtothequantitativeimplicationsofthemodel,weprovidesomeintuitiononitsinner workings,particularlyregardingtheeffectsofcreditconstraintsandtaxationonoccupationalchoice.

Fig.1(a)plotsagentsaccordingtotheircharacteristicsandoccupationalchoices,inanenvironmentwithnotaxes (τf=τn=0) andnocreditconstraintsonformalentrepreneurs(λ=∞).Inthiscase, allentrepreneurs operateinthe formalsector.Moreover,occupationalchoicedependsonlyontalent:ifθissufficientlyhigh,theindividualbecomes anentrepreneur;otherwise,shechoosestobeawageworker.

Fig.1(b)introducestheborrowingconstraintonformalentrepreneurs.Wekeeptaxratesatzero,sothatitisstill notoptimaltooperateintheinformalsector.ThisisthecasestudiedbyEvansandJovanovic(theonlydifferencehere isthatwagesareendogenous).Nowoccupationalchoicedependsonwealthaswellastalent.Inparticular,thereare twomarginsofinefficiencyentailedbytheborrowingconstraint:(i)theintensivemargin,thatis,individualswithhigh

θandlowzbecomeconstrainedentrepreneursandhavetooperateatscaleslowerthanoptimal;and(ii)theextensive margin,thatis,someofthesehigh-talentindividualsprefertobecomewageworkers.Theseeffectsalsoreducethe demandforlaborand,therefore,equilibriumwages.

Fig.2 introduces,inadditionto creditconstraints, the secondsource of frictioninthe model:taxes onformal entrepreneursandonlaborincome.Nowtheinformalsectorbecomesprofitableforsomeindividuals,sincetheycan avoidpayingtaxes.In particular, for agivenlevel of wealth,theleast talented individualsopt for wage working. Increasesintalenttheninduceindividualstobecomeinformalentrepreneurs:sincetheirscaleisrelativelylow,they prefertooperateinformallyinspiteofnothavingaccesstocreditmarkets.Furtherincreasesinθ(forthesamelevelof z)arethenrelatedtolargerscale:accesstocreditmarketsbecomesessential,thusinducingsuchindividualstooperate intheformalsector.

Thisreasoningappliestointermediatevaluesofθ,suchasθ=4inFig.2.However,thereisalsoasetofhighlytalented individualsthatoperateinformally,specificallythosewithverylowlevelsofwealth(upperleftcornerofFig.2).Ifthese individualsweretooperateintheformalsector,theywouldraiseaverylimitedamountofresourcesand,therefore, producewithsubstantiallylowcapital.That wouldbeparticularlycostlysincetheformalsectorfeaturesacapital intensivetechnology.Theseindividualsthereforeprefertheinformalsector,inwhichtechnologyislaborintensive (althoughinferior)andtheydonothavetopaytaxes.

Table2 presentssomedescriptivestatisticsaboutourcalibratedeconomy.About65.6percentofallindividuals

arewageworkers,and17.9percentareentrepreneursoperatingintheformalsector.Theinformalsectoremploysthe

8 DatafromtheBrazilianHouseholdSurvey(PesquisaNacionalporAmostradeDomicílio,PNAD),calculatedannuallybytheBrazilianInstitute ofGeographyandStatistics(IBGE).Weuseonlyindividualsthatareemployers,employeesorself-employed,withages10ormore.Theshareof wageworkersisthenumberofemployeesdividedbythesumofemployees,employersandself-employed.

Table3

Effectoftaxesandborrowingconstraintsonefficiency(%).

(1) (2) (3) (4) τn=0 τn=0.176 τn=0 τn=0.176 τf=0 τf=0 τf=0.345 τf=0.345 λ=∞ – 0.3 10.6 10.8 λ=2 17.3 17.4 38.0 37.0 λ=1 24.3 24.4 50.0 51.0

majorityofworkers(51.7%),butproducesonly41percentoftheoutputinthiseconomy.Thisisbecausesuchsector isbothmorelaborintensiveandlessproductivethantheformalsector.Wageworkersaretheleasttalentedindividuals ofthiseconomy,whileformalentrepreneursareslightlymoretalentedthaninformalonesonaverage.Nonetheless, informalentrepreneursarewealthier,especiallythoseunconstrained:sincetheseindividualsdonotneedtoborrowto operateattheoptimalscale,theychoosetheinformalsectorinordertoavoidpayingtaxes.

4.1. Implicationsforefficiency

Tomeasureefficiency,wecompareourmodel’stotaloutput(formalandinformal)tothatofaneconomywithno distortions.Specifically,letY(λ,τf,τn)bethetotaloutputofaneconomywithparametersλ,τfandτn.Outputinthe absenceofdistortionsisgivenbyY(∞,0,0).Wedefineefficiencygapas1−Y(λ,τf,τn)/Y(∞,0,0).

Table3displaystheefficiencygapforselectedcombinationsoftaxratesandborrowingconstraintparameters.In

column(1),bothtaxratesarezero.Column(2)considersthecaseinwhichtaxesonformaloutputarenull,butthetax rateonlaborincomeispositive.Column(3)doestheopposite,i.e.,allowstaxesonformaloutputtobepositive,but keepstaxesonlaborincomeatzero.Finally,incolumn(4)bothtaxratesarepositive.Asfortheborrowingconstraint parameter,alongwithourcalibratedvalue(λ=2),weconsidertwoextremesituations:λ=∞(thatis,withoutsuch constraint)andλ=1(thatis,noaccesstocreditmarkets,evenforformalentrepreneurs).9

The efficiency gapof ourcalibratedeconomy ishighlighted inbold. Thecombination of taxes andborrowing constraintsgeneratesanefficiencylossof37percent,relativetoaneconomywithnodistortions.Mostofthiseffect isattributedtoborrowingconstraints:theefficiencylossisreducedto10.8percent,whenwemakesuchconstraint unimportant(thatis,whenλisincreasedfrom2toinfinity),whilekeepingtaxratesconstant.

Thoughsmallerinmagnitude,theeffectoftaxesontotaloutputisalsosubstantial:theefficiencylossfallsto17.3 percentwhenonemakesbothtaxratesequaltozero,butkeepsλ=2(column(4)versuscolumn(1)).Thiseffectis basicallydrivenbytaxesonformaloutput(column(4) versuscolumn(2)).Whenonereducesonlythetaxrate on laborincometozero(column(4)versuscolumn(3)),theefficiencygapactuallyincreases.Thisisbecausethefall inτnlowersgrosswages,thusmakingtheinformalsector(whichislaborintensive)moreattractive.Inotherwords, someentrepreneursmigratetotheinformalsector,whichisalsolessproductive,leadingtoafallintotaloutput.

Noticethatthisnegativeeffectofτnisabsentintheextremesituationsλ=1andλ=∞.Thereasonisthat,inthese cases,themovementofentrepreneursacrosssectorsisseverelyreduced.Forinstance,whenλ=1,thereisnoincentive tooperateformally,sinceentrepreneursdonothaveaccesstocreditmarketsineithersector(butintheinformalsector theydonotpaytaxes).Therefore,changesinτnwillnotentailmovementsof individualsacrosssectors.Similarly, whenλ=∞,thereislittleincentivetooperateinformally,whichreducesthemassofindividualsreactingtoanincrease inτn.10

In what follows, we provide furtherdetails onthe mechanisms behindthe effects tax rates andthe borrowing constraintparameteronefficiency.

4.1.1. Changesinλ

Wenowanalyzetheimpactsofchangingtheborrowingconstraintparameteronformalizationandefficiency.Table4

displayspercentagechangesintotaloutput(relativetoourbaselinecalibration,i.e.,λ=2)forselectedvaluesofthe

9 Inallexercises,informalentreprenuershavenoaccesstocreditmarkets. 10Inthesecases,ahighτ

Table4

Effectsofchangingtheborrowingconstraintparameter(%).

1.0 1.5 1.75 2.0 2.25 2.5 3.0

Totaloutput −22.2 −16.5 −5.5 – 3.3 6.1 21.3

Intensivemargin −3.3 −4.3 −1.6 – 1.0 2.2 10.4

Extensivemargin −18.9 −12.2 −3.9 – 2.2 3.8 10.9

Shareofinformaloutput 100.0 80.9 52.1 41.0 35.9 32.3 8.8

Occupationalchoices

Wageworkers 66.5 66.2 65.8 65.6 65.6 65.6 65.1

Formalentrepreneurs 0.0 4.1 13.1 17.9 20.3 21.7 31.0

Informalentrepreneurs 33.5 29.7 21.2 16.5 14.1 12.7 3.9

Table5

Effectsofchangingtaxationonformalbusinesses(%).

f(%) 29.7 30.7 31.2 31.7 32.2 32.7 33.7

Totaloutput 23.4 22.5 21.8 – −5.1 −10.4 −22.8

Intensivemargin 0.0 0.1 0.0 – 0.0 −0.0 −0.0

Extensivemargin 23.4 22.4 21.8 −5.1 −10.4 −22.8

Shareofinformaloutput 0.7 1.8 2.7 41.0 52.2 65.0 99.8

Occupationalchoices

Wageworkers 64.5 64.6 64.6 65.6 65.8 65.9 66.0

Formalentrepreneurs 34.8 33.7 33.0 17.9 14.1 9.9 0.5

Informalentrepreneurs 0.7 1.7 2.5 16.5 20.1 24.2 33.5

borrowingconstraintparameter.Wealsoshowtheshareofoutputproducedintheinformalsector,aswellastheshare ofeachoccupationinthepopulation.Taxratesarekeptattheirbaselinevalues.

Increasingλimpliesthatindividualsintheformalsectorhavemoreaccesstocredit.Thissector,asaresult,becomes moreattractive,leadingtoadecreaseininformaloutput.Totaloutputrisesbecauseoftwochannels:(i)theintensive margin,thatis,individualsthatmaintaintheirstatusesofformalentrepreneurs(constrained)andcanexpandtheirscale sincethereismorecreditavailable,and(ii)theextensivemargin,thatis,individualsthatswitchfromtheothertwo occupationsandbecomeformalentrepreneurs.

Table4alsodecomposestheimpactontotaloutputintothesetwomargins.11Forinstance,raisingλfrom2to2.5

leadstoa6.1percentincreaseintotaloutput;theshareofinformalsectordecreasesfrom41to32.3%.Thiseffect comesmostlyfromtheextensivemargin,i.e.,fromindividualsthatbecome formalentrepreneursasaresultof an increaseλ–specificallyfromentrepreneursthatleavetheinformalsector,sincetheshareofwageworkersisrelatively constantacrossdifferentvaluesofλ.

However,theintensivemarginbecomesmoreimportantasλincreasesfurther.Forinstance,forλ=3,thismargin accountsformorethanhalfofthetotaleffectonoutput.Thisisintuitive:forhighvaluesofλmostofentrepreneurs arealreadyintheformalsector.Furtherincreasesinthisparameter,therefore,caninducethemigrationofveryfew extraentrepreneurs,thusreducingtherelativeimportanceoftheextensivemargin.12

4.1.2. Changesinτf

Table5performsasimilarexercise,butforchangesinτf.Asaresultofincreasingtaxesonformalbusinesses,some

individualsfindmoreprofitabletooperateinformally.Therefore,outputintheinformalsectorrisesattheexpenseof

11 Tocalculatetheintensivemargin,weaddthechangeinoutputacrossentreprenuersthatdidnotaltertheiroccupationalchoicesasaresultofa differentvalueforλ.Theintensivemarginisthechangeinproductionfromentreprenuersthatdidaltertheirstatuses.

12 NoticefromTable4thattheintensivemarginincreasesasλrises,exceptwhenλfallsfrom1.5to1.0.Insuchregion,therearefewformal entreprenuers,sothattheircontributiontotheintensivemarginisquitelimited.Ontheotherhand,reducingλfrom1.5to1.0leadstoafallinthe wage(seeSection4.2),whichlowerscostsespeciallyintheinformalsector(whichislaborintensive),allowingexistinginformalfirmstoexpand theirproduction.Asaresult,theintensivemarginriseswhenλfallsfrom1.5to1.0.

Table6

Effectsofchangingtaxationonlaborincome(%).

n(%) 5.6 11.6 14.6 17.6 20.6 23.6 29.6

Totaloutput −1.1 −0.6 −0.3 – 0.7 7.0 20.6

Intensivemargin 0.5 0.6 0.1 – −0.3 −3.5 −8.2

Extensivemargin −1.6 −1.2 −0.4 1.0 10.5 28.9

Shareofinformaloutput 43.9 42.7 41.9 41.0 39.7 26.8 3.6

Occupationalchoices

Wageworkers 67.6 66.7 66.2 65.6 65.0 64.2 62.3

Formalentrepreneurs 16.1 16.9 17.4 17.9 18.6 23.5 34.3

Informalentrepreneurs 16.3 16.4 16.5 16.5 16.4 12.3 3.4

Table7

Effectoftaxesandborrowingconstraintsoninequality.

(1) (2) (3) (4) τn=0 τn=0.176 τn=0 τn=0.176 τf=0 τf=0 τf=0.317 τf=0.317 λ=∞ 0.391 0.417 0.470 0.493 λ=2 0.434 0.458 0.495 0.517 λ=1 0.454 0.477 0.494 0.516

outputintheformalsector.Moreover,nearly100%ofsucheffectcomesfromtheextensivemargin.Noticethatthe modelisquitesensitiveinthisdimension.13Forinstance,ifτfrisesby0.5percentagepoints,theinformalsectorshare intotaloutputjumpsfrom41to52.2%.Totaloutputfallsasaresult,assomeentrepreneursswitchtoalessproductive technologywhentheymovetotheinformalsector.Theshareofwageworkersalsoincreasesinresponsetohigher taxationonformalentrepreneurs.Thisisbecausetheexpansionof theinformalsector(whichislaborintensive)is associatedwithanincreaseinwages.Asaresult,someindividualsswitchtothisoccupation.

4.1.3. Changesinτn

Table6exhibitsresultsregardingchangesinlaborincometaxation.Aspreviouslynoted,anincreaseinτnraises

efficiency,becauseitmakesgrosswageshigherand,asaresult,reducesrelativeprofitabilityintheinformalsector (whichismorelaborintensive).Thisinducessomeentrepreneurstomovetotheformalsector,wherethetechnology ismoreproductive.Sucheffectappearsintheextensivemargin,whichispositiveforincreasesinτn.Theintensive margin,nonetheless,worksintheoppositeway,sinceentrepreneursthatdonotswitchsectorsfacehighercosts,thus reducing theirscale.Moreover,net wagesfall,leadingtoareduction inthe shareof individualsthat optforwage working.

In spite of the efficiency gains, increasing labor taxation worsensincome inequality inthe model, since most individualsarewageworkers.Inthefollowingsubsection,wediscussthedistributionaleffectsofchangesintaxation andintheborrowingconstraintparameter.

4.2. Implicationsforinequality

WemeasureinequalitybytheincomeGinicoefficient,whichisequalto0.517inourbaselinecalibration.Inother words,themodelisabletogenerateconsiderableinequality,despitenotfeaturingdifferencesinlaborproductivity (inthedata,theaverageBrazilianGiniindexisequalto0.562duringthe2003–2009period).Table7isanalogousto

Table3,butshowstheeffectsoftaxratesandtheborrowingconstraintparameteronincomeinequalityinthemodel.

Ifalldistortionswereremoved,theGiniindexwoulddropto0.391.Eliminatingeachdistortionseparatelywouldalso reduceinequalityinthemodel.Thehighestreductionoccurswhenonemakestaxratesequaltozero.

13Forthisreason,wechosevaluesofτ

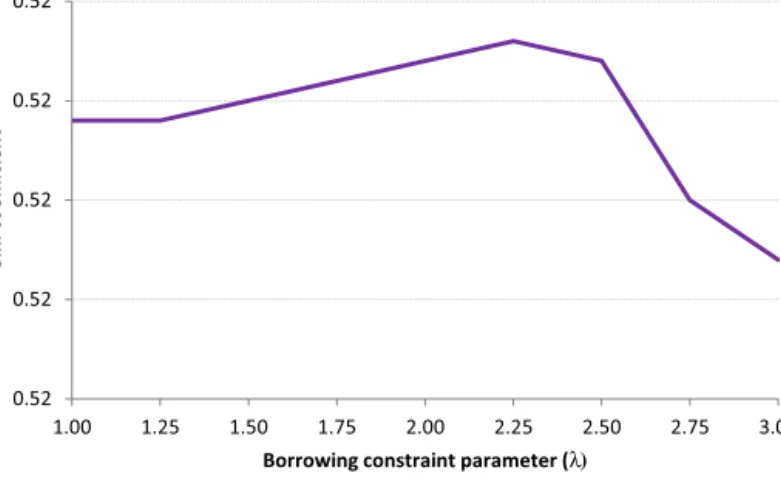

0.52 0.52 0.52 0.52 0.52 1.00 1.25 1.50 1.75 2.00 2.25 2.50 2.75 3.00 G in i c oe ffi ic ie nt

Borrowing constraint parameter (λ)

Fig.3.Effectofborrowingconstraintparameteroninequality.

Furthermore,noticethattheparameterλhasanon-monotoniceffectontheGinicoefficient:raisingλfrom1to2 increasesincomeinequality,butincreasingλfurthertoinfinityreducesthisindex.Fig.3showstheGinicoefficient forseveralvaluesofλ(taxratesremainconstantattheirbaselinevalues).Therelationshipfollowsaninverted“U” shape,whereinequalitypeaksatλroughlyequalto2.25.

Thisoccursbecauseλhastwoeffectsonwages(and,therefore,inequality,sincemostindividualschoose wage workinginthiseconomy),whichworkinoppositeways.Ontheonehand,relaxingborrowingconstraintsboostslabor demand,asfirmsintheformalsectorareabletoreachlargerscalesofproduction.Ontheotherhand,theincreaseinλ

inducesmovementsofentrepreneursfromtheinformaltotheformalsector,whichlowerslabordemandsinceinformal firmsoperatealabor-intensivetechnology.Whenλisclosetoone(andnearlyalloutputisproducedintheinformal sector),thesecondeffectdominates.Asλincreasesfurther,thefirsteffectbecomesmoreimportant.

Asmallertaxrateonlaborincomelowersefficiency,butreducesinequality,sincethenetwageincreasesinresponse toalowerτn.Ontheotherhand,reductionsinτf leadtolowerwages,sincetheystimulatethemigrationfromthe informaltotheformalsector(whichislesslaborintensive).Sucheffectishoweverquantitativelysmall,andafallin

τfendsuploweringinequality.Thisfollowsbecauseentrepreneursmovetotheformalsector,wheretheirincomeis lessdependentontheirwealththanintheinformalsector.

5. Concludingremarks

Thispaperanalyzedtheeffectsoftaxationandcreditmarketfrictionsonoccupationalchoice,aggregateefficiency andincomeinequality,inanenvironmentwherealargefractionofoutputisproducedintheinformalsector.Inparticular, weextendedthemodelofEvansandJovanovic(1989)toconsidertwosectors:theformalsector,inwhichentrepreneurs havelimitedaccesstocreditmarketsandmustpaytaxes;andtheinformalsector,inwhichentrepreneurscanevadethe paymentoftaxes,buthavetorelyexclusivelyontheirwealthtofinancetheircapital.Individualsareheterogeneous intheir wealthandentrepreneurialtalent,anddecidebetweenthreeoccupations:wage worker,entrepreneurinthe formalandentrepreneurintheinformalsector.Inaddition,theinformalsectorisbothlessproductiveandmorelabor intensivethantheformalsector.

ThemodeliscalibratedtoapproximatefeaturesoftheBrazilianeconomyinthe2000s.Forourbaselineparameters, the frictions included in the model are able to generatea considerable degreeof inefficiency: total output is 37 percentbelowthatofaneconomywithnodistortions.Thisislargelyattributedtocreditfrictions,buttaxesonformal businessesarealsoimportant.Relaxingsuchfrictionscanthehavealargeimpactontotaloutput,mostlybecauseit inducesentrepreneurstoswitchtotheformalsector,whichfeaturesasuperiortechnology.Removingallfrictionsalso reducesconsiderablyincomeinequalityinthemodel.

Ourworkleavessomeinterestingquestionsforfutureresearch.Forinstance,weassumedthatinformalentrepreneurs cannotborrowanyresourcestofinancetheircapital.Onecouldarguethat,inreality,theyhavesomeaccesstocredit, althoughatahighercostthanformalbusinesses.MerlinandTeles(2014)supposethatinformalentrepreneursborrow fundsthroughpersonalcreditlines(atsubstantiallyhigherratesthanthroughbusinesscreditlines)toinvestintheir

firms. Incorporatingthisfeature inoursettingwould certainlyreducetheimpactof removingfrictions(especially borrowingconstraintsandthetaxesonformalenterprises),sinceitwouldlowertheincentivestooperateformally.On theotherhand,thiswouldforceustorecalibratethemodel,sothattheshareoftheinformalsectorwouldapproximate thatinthedata.Inotherwords,wewouldhavetoreducetherelativeefficiencyparameterψ,whichwouldprobably increaseaggregateinefficiencyinourbaselinecalibration.

Anotherinterestingextensionistoendogenizewealththroughsavingsdecisions.Theoptiontooperateinformally (andtonotpaytaxes)mayinducesomeentrepreneurstoaccumulatelittlewealth.Thiscouldgiverisetopovertytraps andincreaseevenmorethelevelofaggregateinefficiencyfoundinmodel.

References

Amaral,P.S.,Quintin,E.,2006.Acompetitivemodeloftheinformalsector.J.Monet.Econ.53,1541–1553.

Antunes,A.R.,Cavalcanti,T.V.V.,2007.Startupcosts,limitedenforcement,andthehiddeneconomy.Eur.Econ.Rev.51,203–224.

Atkeson,A.,Kehoe,P.J.,2005.Modelingandmeasuringorganizationcapital.J.Polit.Econ.113,1026–1053.

Banerjee,A.V.,Moll,B.,2010.Whydoesmisallocationpersist?Am.Econ.J.:Macroecon.2,189–206.

Blanchflower,D.,Oswald,A.J.,1998.Whatmakesanentrepreneur.J.LaborEcon.16,26–60.

Buera,F.,2008.Persistencyofpoverty,financialfrictionsandentrepreneurship.Mimeo.

Cagetti,M.,DeNardi,M.,2006.Entrepreneurship,frictionsandwealth.J.Polit.Econ.114,835–870.

Davies,J.B.,Sandstrom,S.,Shorrocks,A.,Wolf,E.N.,2011.Thelevelanddistributionofglobalhouseholdwealth.Econ.J.121,223–254.

DePaula,A.,Scheinkman,J.A.,2011.Theinformalsector:anequilibriummodelandsomeempiricalevidencefromBrazil.Rev.IncomeWealth 57,S8–S26.

D’Erasmo,P.N.,Moscoso-Boedo,H.J.,2012.Financialstructure,informalityanddevelopment.J.Monet.Econ.59,286–302.

Evans,D.,Jovanovic,B.,1989.Anestimatedmodelofentrepreneurshipchoiceunderliquidityconstraints.J.Polit.Econ.97,808–827.

Gasperini,B.O.,(MAthesis)2010.Créditoeempreendedorismo:confrontandoeventosagregadosemicrodados.Department ofEconomics, UniversityofSaoPaulo,Brazil.

Gollin,D.,2002.Gettingincomesharesright.J.Polit.Econ.110,458–474.

Hsieh,C.,Klenow,P.,2007.MisallocationandmanufacturingTFPinChinaandIndia.Q.J.Econ.124,1403–1448.

Jeong,H.,Townsend,R.M.,2007.SourcesofTFPgrowth:occupationalchoiceandfinancialdeepening.Econ.Theory32,179–221.

LaPorta,R.,Shleifer,A.,2008.Theunofficialeconomyandeconomicdevelopment.Brook.Pap.Econ.Activity39,275–363.

Lucas,R.,1978.Onthesizedistributionofbusinessfirms.BellJ.Econ.9,508–523.

Merlin,G.,Teles,V.K.,2014.Financialfrictions,informalityandincomeinequality.SaoPauloSchoolofEconomics,WorkingPaper#374.

Ordonez,J.C.L.,2014.Taxcollection,theinformalsector,andproductivity.Rev.Econ.Dyn.17,262–286.

Paulson,A.L.,Townsend,R.M.,2004.EntrepreneurshipandfinancialconstraintsinThailand.J.Corp.Finance10,229–262.

Paulson,A.L.,Townsend,R.M.,Karaivanov,A.,2006.Distinguishinglimitedliabilityfrommoralhazardinamodelofentrepreneurship.J.Polit. Econ.114,644–671.

Pereira,F.M.,ElleryJr.,R.G.,2011.Políticafiscal,choquesexternosecicloeconômiconoBrasil.Economia12,445–474.

Prado,M.,2011.Governmentpolicyintheformalandinformalsectors.Eur.Econ.Rev.55,1120–1136.

Rauch,J.E.,1991.Modellingtheinformalsectorformally.J.Dev.Econ.35,33–47.

Restuccia,D.,Rogerson,R.,2008.Policydistortionsandaggregateproductivitywithheterogeneousplants.Rev.Econ.Dyn.11,707–720.

Schneider,F.,2005.Shadoweconomiesaroundtheworld:whatdowereallyknow?Eur.J.Polit.Econ.21,598–642.

Schneider,F.,2012.Theshadoweconomyandworkintheshadow:whatdowe(not)know?IZADiscussionPapers6423,InstitutefortheStudy ofLabor(IZA).