Accessing information sharing and information quality

in supply chain management

Suhong Li

a, Binshan Lin

b,⁎

aComputer Information System Department, Bryant University, 1150 Douglas Pike, Smithfield, RI 02917-1284, United States bCollege of Business Administration, Louisiana State University in Shreveport, Shreveport, LA 71115, United States

Received 8 November 2004; received in revised form 1 February 2006; accepted 8 February 2006 Available online 27 March 2006

Abstract

This paper empirically examines the impact of environmental uncertainty, intra-organizational facilitators, and inter-organizational relationships on information sharing and information quality in supply chain management.

Based on the data collected from 196 organizations, multiple regression analyses are used to test the factor impacting information sharing and information quality respectively. It is found that both information sharing and information quality are influenced positively by trust in supply chain partners and shared vision between supply chain partners, but negatively by supplier uncertainty. Top management has a positive impact on information sharing but has no impact on information quality. The results also show that information sharing and information quality are not impacted by customer uncertainty, technology uncertainty, commitment of supply chain partners, and IT enablers.

Moreover, a discriminant analysis reveals that supplier uncertainty, shared vision between supply chain partners and commitment of supply chain partners are the three most important factors in discriminating between the organizations with high levels of information sharing and information quality and those with low levels of information sharing and information quality. © 2006 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

Keywords:Information sharing; Information quality; Supply chain management

1. Introduction

As competition in the 1990s intensified and markets became global, so did the challenges associated with getting a product and service to the right place at the right time at the lowest cost. Organizations began to realize that it is not enough to improve efficiencies within an organization, but their whole supply chain has to be made competitive. The understanding and practicing of Supply Chain Management (SCM) has become an

essential prerequisite for staying competitive in the global race and for enhancing profitably[12,44,51].

Information sharing is a key ingredient for any SCM system[37]. Many researchers have suggested that the key to the seamless supply chain is making available undistorted and up-to-date marketing data at every node within the supply chain [12,54]. By taking the data available and sharing it with other parties within the supply chain, an organization can speed up the information flow in the supply chain, improve the efficiency and effectiveness of the supply chain, and respond to customer changing needs quicker. Therefore, information sharing will bring the organization compet-itive advantage in the long run.

⁎ Corresponding author.

E-mail addresses:sli@bryant.edu(S. Li),blin@lsus.edu(B. Lin). 0167-9236/$ - see front matter © 2006 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved. doi:10.1016/j.dss.2006.02.011

The advantage of information sharing in SCM has been intensively discussed [10]. Information sharing improves coordination between supply chain processes to enable the material flow and reduces inventory costs. Information sharing leads to high levels of supply chain integration [24] by enabling organizations to make dependable delivery and introduce products to the market quickly. Quality information sharing contributes positively to customer satisfaction[48]and partnership quality [30]. Information sharing impacts the supply chain performance in terms of both total cost and service level[63]. According to Lin et al.[33], the higher level of information sharing is associated with the lower total cost, the higher order fulfillment rate and the shorter order cycle time.

While information sharing is important, the signifi-cance of its impact on the performance of a supply chain depends on what information is shared, when and how it is shared, and with whom[13,22]. Literature is replete with example of the dysfunctional effects of inaccurate/ delayed information, as information moves along the supply chain[35]. Divergent interests and opportunistic behavior of supply chain partners, and informational asymmetries across supply chain affect the quality of information[17]. It has been suggested that organiza-tions will deliberately distort information that can potentially reach not only their competitors, but also their own suppliers and customers[35]. It appears that there is a built-in reluctance within organizations to give away more than minimal information [6] since infor-mation disclosure is perceived as a loss of power and companies fear that information may leak to potential rivals.

To facilitate quality information sharing across supply chains, an understanding of the factors influenc-ing information sharinfluenc-ing is needed so that a strategy may be developed to overcome the barriers preventing information sharing and encourage seamless informa-tion flow in supply chains. Previous studies have addressed the importance of certain factors in informa-tion sharing and informainforma-tion quality in SCM but few studies have considered simultaneously the impact of environmental factors, intra-organizational factors, and inter-organizational factors on information sharing and information quality in SCM.

To fill this gap, this paper first identifies a set of factors, including environmental uncertainty (customer uncertainty, supplier uncertainty, and technology uncer-tainty), intra-organizational facilitators (top manage-ment support and IT enablers), inter-organizational relationships (trust in supply chain partners, commit-ment of supply chain partners, and shared vision

between supply chain partners), that may impact information sharing and information quality in SCM. The rationale to select the above factors are illustrated as follows: past researchers consider environmental uncer-tainty an important driver for information sharing and information quality and organizations will build strate-gic partnerships with their trading partners to reduce the risk when the environmental uncertainty is high [2,11,28]. Within an organization, on one hand, top management is needed in providing vision, guidance, and support for quality information sharing[30]. On the other hand, the implementation of information technol-ogy enables organizations to share information effi-ciently and securely [32,58]. Moreover, a good inter-organizational relationship based on trust, commitment and shared vision is necessary to encourage information sharing and to overcome the fear of information disclosure and the loss of power over competitor[7,46]. Based on the data collected from 196 organizations of various sizes and industries, multiple regression analyses are used to test the factors impacting information sharing and information quality in SCM, followed by a discriminant analysis testing the relative importance of each of eight factors in discriminating between organizations with high levels of information sharing and information quality and those with low levels of information sharing and information quality. It is found that supplier uncertainty and inter-organiza-tional relationships (trust, commitment and shared vision) are most critical factors in determining the level of information sharing and information quality in SCM and in distinguishing organizations with high levels of information sharing and information quality and those with low levels of information sharing and information quality.

2. Theoretical framework and hypothesis development

Fig. 1 presents a framework displaying the factors impacting information sharing and information quality in SCM and Table 1 summarizes the impact of each factor on information sharing and information quality. It should be pointed out that the antecedents of informa-tion sharing and informainforma-tion quality identified in this paper can not be considered complete. Other factors, such as firm size, order size, industry type and supply chain structure may impact information sharing and information quality. Though these factors are of great interest, they are not included due to the length of the survey and the concerns regarding the parsimony of this research.

This section will discuss each variable in the framework and the hypothesized relationships briefly. 2.1. Information sharing and information quality

Information sharing refers to the extent to which critical and proprietary information is communicated to one's supply chain partner[38]. Many researchers have emphasized the importance of information sharing in SCM practice. Lalonde [27] considers sharing of information as one of five building blocks that characterize a solid supply chain relationship. Accord-ing to Stein and Sweat[49]supply chain partners who exchange information regularly are able to work as a single entity. Together, they can understand the needs of the end customer better and hence can respond to market change quicker. Moreover, Yu et al.[62]point out that the negative impact of the bullwhip effect on a supply chain can be reduced or eliminated by sharing information with trading partners. The empirical find-ings of Childhouse and Towill[12]reveal that simplified material flow, including streamlining and making highly visible all information flow throughout the chain, is the key to an integrated and effective supply chain.

Information quality includes such aspects as the accuracy, timeliness, adequacy, and credibility of information exchanged[38]. While information sharing is important, the significance of its impact on SCM depends on what information is shared, when and how it is shared, and with whom [13]. Jarrell [24]notes that sharing information within the entire supply chain can create flexibility, but this requires accurate and timely

information. It is well known that information notori-ously suffers from delay and distortion as it moves up the supply chain[17,35]. Moreover, as a consequence of the traditional culture, organizations can deliberately distort order information to mask their intent to competitors, and also to their own suppliers and customers [35]. Organizations usually perceive infor-mation disclosure as a loss of power. This will likely lead to further distortion as orders are passed along the chain. To reduce information distortion and improve the quality of information shared, information shared has to be as accurate as possible and organizations must ensure that it flows with minimum delay and distortion. 2.2. Environmental uncertainty

Environmental uncertainty is a critical external force driving information sharing in SCM. In today's competitive environment, markets are becoming more international, dynamic, and customer driven; customers are demanding more variety, better quality, higher reliability and faster delivery[53]; product life cycle is shortening and product proliferation is expanding; technological developments are occurring at a faster pace. To respond to such uncertain environment, organizations have increased their level of outsourcing and cooperation with their customers and suppliers[26]. Environmental uncertainty can be classified in terms of source of uncertainty. For example, Gupta and Wilemon[19]consider perceived environmental uncer-tainties coming from the following four factors: 1) in-creased global competition, 2) continuous development Environmental Uncertainty

Customer Uncertainty Supplier Uncertainty Technology Uncertainty

Intra-Organizational Facilitators

Top Management Support IT enablers

Inter-Organizational Relationships

Trust in Supply Chain Partner

Commitment of Supply Chain Partner

Shared Vision between

Information Sharing Information Quality H1a H1b H2a H2b H3a H3b

of new technologies that quickly cause existing products to be obsolete, 3) changing customer demand needs and requirements which truncate product life cycles, and 4) increasing need for involvement of external organiza-tions such as suppliers and customers. Ettlie and Reza [15] view perceived environmental uncertainty as unexpected changes of customers, suppliers, and

technology. Consistent with this perspective, environ-mental uncertainty in this study is defined as including the uncertainty from customers, suppliers, and technol-ogy. The following section will discuss each of these three uncertainties respectively.

Customer uncertaintyis defined as the extent of the change and unpredictability of the customer's demands

Table 1

Information sharing and information quality impacts Independent variables Dependent variables

Information sharing Information quality Environmental

uncertainty

Customer uncertainty

•Increasing unpredictability of the customer's demands leads an organization to share more information with its supply chain partners in order to respond to customers' changing needs[18,56].

•Increasing unpredictability of the customer's demands leads an organization to share accurate information in a timely way[18,56].

Supplier uncertainty

•Unreliable suppliers will impact the whole supply chain and an organization will build partnership with a few suppliers to share information in order to reduce supplier uncertainty[41,62].

•Supplier uncertainty makes it necessary to share quality information in order to reduce uncertainty from suppliers and the impact of such uncertainty on whole supply chain[41,62].

Technology uncertainty

•The development of IT provides numerous opportunities for organizations to increase the level of information sharing[13,55].

•The development of IT enables organizations to share information in a timely and effective way[13,55].

•Today's rapid technology change forces organizations to share information in order to keep up with such change[26]. Intra-organizational

facilitators

Top management support

•Top management is needed in providing vision, guidance, and support in sharing information[36,60].

•Top management needs to understand the importance of sharing quality information and make sure information is shared without any delay and distortion[17].

•Top management is needed to overcome the reluctance of information sharing and create an organizational culture conducive to

information sharing[30].

IT enablers •IT enables organization to increase the level of information sharing[13,24,48].

•IT enables organization to share information simultaneously across the supply

chain[13,24,48].

•IT enables organization to open up new possibilities for increasing value through information sharing[9].

•IT supports secured information sharing[32].

•IT enables an organization to share information timely, accurately and reliably[32,58,43]. Inter-organizational

relationships

Trust in supply chain partners

•Lack of trust has been considered as a common cited obstacle to information sharing[39,47].

•Trust stimulates favorable attitudes and behaviors to ensure the quality of information shared[45].

•Trust reduces the fear of information disclosure and loss of power in relation to the information sharing.

•Allowing an outside organization to view transaction-level data places a premium on trust[45]. Commitment of

supply chain partners

•Commitment has been identified as the variable that discriminates between relationships that continue and that break down[59].

•Commitment“ups the ante”and makes it more difficult for partners to act in ways that might adversely affect the quality of information shared.

•Commitment can involve trusting the partners with proprietary information and other sensitive information, an indicator of high level of information sharing.

Shared vision between supply chain partners

•The lack of shared vision between supply chain partners will lead to less information sharing[7,36].

•The lack of shared vision (such as the cultural and other differences between the parties) will receive more resistance and encourage negative behaviors, thus reducing the quality of information sharing.

•Collaboration within a supply chain (such as information sharing) can be achieved only to the extent that trading partners share a common

and tastes. The traditional seller market, where demand outstripped supply, has been replaced by fast moving, sophisticated, customer-led competition. The customer demands for products and services are becoming in-creasingly volatile and uncertain in terms of volume, mix, timing, and place. Customers today want more choice, better service, higher quality, and faster delivery [9,56]. Moreover, competitive pressure in a global marketplace has greatly altered the traditional nature of the customer choice.

Supplier uncertainty is defined as the extent of change and unpredictability of the suppliers' product quality and delivery performance. There are many sources of supplier uncertainties: supplier's engineering level, supplier's lead-time, supplier's delivery depend-ability, quality of incoming materials, and so on [29]. Uncertainty caused by suppliers, such as delayed or broken materials, will postpone or even stop an organization's production process. Furthermore, these uncertainties will propagate through the supply chain in the forms of amplification of ordering variability, which leads to excess safety stock, increased logistics costs, and inefficient use of resources [62]. A manufacturer with key suppliers that have poor quality and delivery records will find it very difficult to provide high levels of customer service even in a stable environment. If placed in a rapidly changing environment, this manu-facturer will be eliminated from participation in the competitive game[41].

Technology uncertainty is defined as the extent of change and unpredictability of technology development in an organization's industry. The development of IT provides numerous opportunities for organizations. For example, the breakthroughs in IT have fueled the movement toward supply chain and business process integration[13], brought out many benefits to an organi-zation and made true supply chain integration possible [55]. The advanced information systems reduce the tran-saction costs associated with the control of goods flow and make a quick response to customer orders.

Technology development provides not only oppor-tunities, but also threats, for individual organizations. For example, the development of IT will increase the competition base through easy access to global organizations of suppliers; hence, competition is no longer local but international [16]. Given the quick obsolescence of components in the computer industry, organizations need to periodically invest in new systems [42]. In addition, IT is changing the level of customer intimacy within the supply chain and increasing customer and consumer expectations, for example, from “during business hours with a two to three day

business delivery” has become “24 h by 7 days with immediate or same day delivery”. Therefore, IT is accelerating the shift in power from producers to the consumer's demands for responsiveness and flexibility [52].

2.2.1. The impact of environmental uncertainty on information sharing and information quality

Many researchers have considered environmental uncertainty an important driver for information sharing and information quality in SCM [2,11]. In a highly uncertain environment with changing markets, organiza-tions tend to build strategic partnership with their supply chain members to share information, increase organiza-tional flexibility, and reduce the risk associated with the uncertainty. Lambe and Spekman [28] suggest that uncertain industry structure and market environment encourage the formation of strategic supplier part-nership. Mentzer et al.[36]agree that high technology uncertainty will drive organizations to form strategic partnerships with suppliers and to share information with their trading partners as technology change is largely uncontrollable by individual organizations. The threat from competitors will impel organizations to increase customer satisfactions and loyalty by sharing timely information with customers. Grover [18]suggests that environmental uncertainty is an important factor influ-encing information sharing and cooperation within supply chain partners. The above arguments lead to: Hypothesis 1a. The higher the level of environmental uncertainty (including customer uncertainty, supplier uncertainty and technology uncertainty), the higher the level of information sharing in SCM.

Hypothesis 1b. The higher the level of environmental uncertainty (including customer uncertainty, supplier uncertainty and technology uncertainty), the higher the level of information quality in SCM.

2.3. Intra-organizational facilitators

This paper considers top management support and IT enablers as the intra-organizational facilitators for information sharing and information quality in SCM.

Top management supportis defined as the degree of top manager's understanding of the specific benefits of and support for quality information sharing with supply chain partners. A number of researchers [5,20] have regarded top management support as the most important driver for any successful change in the organization. Top management vision plays a critical role in shaping an organization's values and orientation. To implement

information sharing in supply chains, top management must understand and embrace the significant operational and market impacts of partnering and develop a good understanding of their potential partners and their top management[36].

IT enablersare defined as the information technology used to facilitate information sharing and information quality in SCM. Developments in information technol-ogy have fueled the movement toward supply chain and business process integration[13]. Organizations cannot effectively manage cost, provide superior customer service, and be leaders in SCM without leading-edge information systems[55]. The transaction cost perspec-tive can be used to explain the impact of IT on the creation of inter-organizational information sharing and coordination [14]. Transaction costs involve costs of writing, monitoring, and enforcing contracts, as well as costs of locating potential trading partners. If these coordination costs are directly influenced by IT capabilities, actual transaction costs can be significantly lowered and economies of“outsourcing”can be more favored over that of“vertical integration”.

The broad adoption of core IT enablers, such as electronic data interchange (EDI), Internet, and extra-nets, have helped many organizations achieve opera-tional excellence and competitive advantage [25]. By reviewing relevant literature, five IT enablers are iden-tified as influencing information sharing and informa-tion quality in SCM and are listed below:

1) Electronic Data Interchange (EDI). The transfer of data in an agreed upon electronic format from one organization's computer program to one or more organizations' programs.

2) Electronic Fund Transfer (EFT). The transfer of a certain amount of money from one account to another through value added network (VAN) or Internet.

3) Internet. A public and global communication net-work that provides direct connectivity to anyone over a local area network (LAN) or Internet service provider (ISP).

4) Intranet. A corporate LAN or wide area network (WAN) that uses Internet technology and is secured behind an organization's firewalls. The intranet sup-ports and promotes more effective internal informa-tion sharing and an organizainforma-tion's internal business processes.

5) Extranet. A collaborated network that uses Internet technology to link businesses with their supply chain and provides a degree of security and privacy from competitors.

2.3.1. The impact of top management support on information sharing and information quality

Information sharing and information quality must have the support of top management. Top management has to share an understanding of the specific benefits of information sharing to overcome the inevitable diver-gence of interests between participating organizations [30]. Top management support is needed in integrating information sharing strategy in SCM into an organiza-tion's overall business strategy and getting the resources required for the implementation of information sharing [9,60]. Top management must understand the impor-tance of information sharing and provide vision, guidance, and support for its implementation. As described previously, information is generally viewed as providing an advantage over competitors which may cause organizations to resist sharing with their partners. To overcome this reluctance of information sharing, top management must understand its benefits and create an organizational culture conducive to information sharing and make sure information is shared without delay and distortion. The above arguments lead to:

Hypothesis 2.a1. The higher the level of top manage-ment support, the higher the level of information sharing in SCM.

Hypothesis 2.b1. The higher the level of top manage-ment support, the higher the level of information quality in SCM.

2.3.2. The impact of IT enablers on information sharing and information quality

Many researchers consider IT a great enabler for information sharing and information quality in SCM [13,23,48]. IT enables coordination across organization-al boundaries to achieve new levels of efficiency and productivity [34] and opens up new possibilities for increasing value through better communication and information sharing [9]. The adoption of different IT will facilitate information sharing and quality in SCM. For example, the usage of EDI can support secured information sharing between trading partners[32] and contribute to partnership satisfaction, success, and longevity [57]. Internet extends the scope of SCM practice by providing a cost effective communication backbone so that information can be shared efficiently and effectively between supply chain partners [58], while intranet can be used to support and promote more effective internal information sharing[58]. Meanwhile, information and process changes can be communicated to the business partners faster and more accurately through extranet [43]. Without the support of IT

enablers, the quality information sharing is impossible in SCM. It is hypothesized that:

Hypothesis 2.a2. The higher the usage of IT enablers, the higher the level of information sharing in SCM. Hypothesis 2.b2. The higher the usage of IT enablers, the higher the level of information quality in SCM. 2.4. Inter-organizational relationships

Inter-organizational relationship refers to the degree of trust, commitment, and shared vision between supplier partners. IT can be used to easily link physical supply chain processes, but not inter-organizational relationships. Without a foundation of effective inter-organizational relationship, any effort to manage the flow of the information or materials across the supply chain is likely to be unsuccessful [21]. Trust and commitment are needed to build long-term cooperative relationships between supply chain partners[48,50].

Achrol et al. [1] identify commitment, trust, group cohesiveness, and motivation of alliance participants as critical to inter-organization strategic alliances. Bucklin and Sengupta[8]consider organizational compatibility as one of the key predictors of effective inter-organizational relationships. This study considers inter-organizational relationship as including three sub-dimensions: trust in trading partners, commitment of trading partners, and shared vision between trading partners.

Trust in trading partnersis defined as the willingness to rely on a trading partner in whom one has confidence [38,48]. Trust is conveyed through faith, reliance, belief, or confidence in the supply chain partner, viewed as a willingness to forego opportunistic behavior[48]. Trust has been considered by many researchers to be the essential factor in most productive partner relationships [59]. Parties who trust one another can find ways to work out difficulties such as power, conflict, and lower profitability. Trust stimulates favorable attitudes and behaviors[45]. Moreover, allowing an outside organi-zation to view transaction-level data places a premium on trust between trading partners because of the competitive risks associated with this type of access [61].

Commitment of trading partners refers to the willingness of buyers and suppliers to exert effort on behalf of the relationship [38,48]. Commitment is an enduring desire to maintain a valued relationship. It incorporates each party's intention and expectation of continuity of the relationship, and willingness to invest resources in SCM[36]. Commitment has been identified

as the variable that discriminates between relationships that continue and that break down [59]. Commitment can involve trusting the suppliers with proprietary information and other sensitive information. To a large degree, commitment“ups the ante”and makes it more difficult for partners to act in ways that might adversely affect overall supply chain performance.

Shared vision between trading partnersis defined as the degree of similarity of the pattern of shared values and beliefs between trading partners [1,30]. Shared vision is therefore the extent to which partners have beliefs in common about what behaviors, goals, and policies are important or unimportant, appropriate or inappropriate, and right or wrong[4]. It is obvious that supply chain members with similar organizational cultures should be more willing to trust their partners. Spekman et al. [48] even suggest that collaboration within a supply chain can be achieved only to the extent that trading partners share a common“world view”of SCM. Organizational incompatibilities between allied organizations, in terms of reputations, job stability, strategic horizons, control systems, and goals, will lead to less information sharing[36].

2.4.1. The impact of inter-organizational relationships on information sharing and information quality

As pointed out by many researchers, information technology is only part of the solution to information sharing and information quality in SCM. Without good inter-organizational relationships based on such intan-gibles as trust, commitment, and shared vision, organizations will be reluctant to share information with their supply chain partners because of the fear of information disclosure and the loss of power over competitor. Lack of trust among suppliers and manu-facturers has prevented them from establishing partner relationships[46]. Boddy et al.[7]explore empirically partnership between suppliers and customers through an interaction model and find that lack of shared vision (such as the cultural and other differences between the parties) causes difficulty in cooperation at first. Actions are then taken to improve cooperative behaviors that support further co-operation between the organizations. The above arguments lead to:

Hypothesis 3a. The higher the level of inter-organiza-tional relationship (including trust in trading partners, commitment of supply chain partners, and shared vision between supply chain partners), the higher the level of information sharing in SCM.

Hypothesis 3b. The higher the level of inter-organiza-tional relationship (including trust in trading partners,

commitment of supply chain partners, and shared vision between supply chain partners), the higher the level of information quality in SCM.

3. Research methodology

This section describes the research methodology employed to test the hypothesized framework presented inFig. 1. The background for the empirical study is first described, followed by a description of the research instrument used for data analyses.

Empirical data for testing the research framework was collected via a field survey. Six constructs were measured in this study: information sharing, information quality, environmental uncertainty, top management support, IT enablers, and inter-organizational relation-ships. All constructs were developed and tested using four phases: (1) item generation, (2) pre-pilot study, (3) pilot study, and (4) large-scale data analysis. The items for each construct were generated through a compre-hensive literature review. In the pre-pilot study, these items were reviewed by six academicians and re-evaluated through structured interviews with three prac-titioners who were asked to comment on the appro-priateness of the research constructs. Based on the feedback from the academicians and practitioners, re-dundant and ambiguous items were either modified or eliminated. New items were added wherever deemed necessary.

In the pilot study stage, the three round Q-sort method was used to pre-assess the convergent and discriminant validity of the scales. Purchasing/produc-tion managers were requested to act as judges and sort the items into the respective construct. To assess the reliability of the sorting conducted by the judges, three different measures were used: the inter-judge raw agreement scores, Cohen's Kappa, and item placement ratios. In the third round, the inter-judge raw agreement scores averaged 0.92, the initial overall placement ratio of items within the target constructs was 0.97, and the Cohen's Kappa score averaged 0.90. At this stage the statistics suggested an excellent level of inter-judge agreement indicating a high level of reliability and construct validity.

3.1. Large-scale methods

This study sought to choose respondents who can be expected to have the best knowledge about the operation and management of the supply chain in his/her organization. Based on literature and recommendations from practitioners, it was decided to choose managers

who are at higher managerial levels as respondents for the current study.

Mailing lists were obtained from two sources: the Society of Manufacturing Engineers (SME) and the at-tendees at the Council of Logistics Management (CLM) conference in New Orleans, 2000. Six SIC codes were covered in the study: 25 “Furniture and Fixtures”, 30 “Rubber and Plastics”, 34“Fabricated Metal Products”, 35 “Industrial and Commercial Machinery”, 36 “ Elec-tronic and Other Electric Equipment”, 37“ Transporta-tion Equipment”. The final version of the questionnaire, measuring all the items on a five point scale, was administrated to 3137 target respondents. The survey was sent in three waves. There were 196 complete and usable responses, representing a response rate of approximately 6.3%.

A significant problem with organizational-level re-search is that senior and executive-level mangers receive many requests to participate and have very limited time. Because this interdisciplinary research collects informa-tion from several funcinforma-tional areas, the size and scope of the research instruments must be large and time consuming to complete. This further contributes to the low response rate. While the response rate was less than desired, the makeup of respondent pool was considered excellent. Among the respondents, almost 20% of the respondents are CEO/President/Vice President/Director. About half of the respondents are managers, some identified them as supply chain manager, plant manager, logistics manager or IT manager in the questionnaire. The areas of expertise were 30% purchasing, 47% manufacturing production, and 30% distribution/trans-portation/sales. It can be seen that respondents have covered all the functions across a supply chain from purchasing, to manufacturing, to distribution and transportation, and to sales. Moreover, about 30% of the respondents are responsible for more than one job function, and they are expected to have a broad view of SCM practice in their organization.

This research did not investigate non-response bias directly because the mailing list had only name and addresses of the individuals and not any organizational details. Hence, a comparison was made between those subjects who responded after the initial mailing and those who responded to the second/third wave[2,38]. Using the

χ2

statistic andpb0.05, it was found that there were no significant differences between the two groups in em-ployment size, sales volume, and respondent's job title. An absence of non-response bias is therefore inferred.

Based on 196 responses, all construct were validated with the following objectives in mind: purification, uni-dimensionality, reliability, convergent and discriminant

validity. The final list of items for each construct is listed in Appendix A. All constructs except IT enablers were estimated using multiple items, fully anchored, five-point Liker scales ranging from“Strongly disagree”to “Strongly agree.” The items for IT enablers were estimated based on five-point Liker scale ranging from “Not at all”to“To a great extent.”Except for customer uncertainty, at least three items were included per individual construct for adequate reliability as recom-mended by Nunnally[40].

Table 2 shows the correlation matrix of the independent variables. It can be seen that there exist strong correlations between each sub-construct of environmental uncertainty and inter-organizational rela-tionships, indicating good convergent validity of those two construct. No significant relationship is found be-tween top management support and IT enablers. Obviously, they represent two independent factors and thus will be treated as independent construct in the following validation of discriminant validity. Discrim-inant validity can be assessed by comparing the minimum inner-scale item-to-item correlation with the correlations of items to outer-scale-items. If the number of “violations”(i.e., cases where correlation of item to outer-scale-items being higher than the minimum inner-scale item-to-item correlation) is less than half of all comparisons, we determine that the scale has discrim-inant validity. An examination of the correlation matrix to assess discriminant validity reveals a total of 3 vio-lations out of 44 comparisons. None of the counts for each item exceed half of the potential comparisons. Therefore, they exhibit good discriminant validity. 4. Data analysis and discussion of results

First, information sharing and information quality, and the factors impacting information sharing and

information quality are discussed based on the means. Next, regression analyses were used to see which factors have significant impact on information sharing and information quality, followed by a discriminant analysis to test the importance of each factor in distinguishing between organizations with high levels of information sharing and information quality and those with low levels of information sharing and information quality. 4.1. The means of information sharing, information quality and the influencing factors of information sharing and information quality

Composite score is used to represent each factor by taking the average score of all items for that dimension. Table 3shows the mean and standard deviation of each factor. It can be seen that the levels of information sharing and information quality in organizations are 3.31 and 3.33 respectively (on a scale of 1–5). In terms of environmental certainty, the levels of customer and technology uncertainty in surveyed organizations are high, represented by means of 3.60 and 3.59 respec-tively, while the level of supplier uncertainty is low with a mean of 2.87. For intra-organizational factors, the level of top management support for SCM is high in surveyed organizations (3.66), while the level of IT enablers is low with a mean of 2.47, indicating organizations have not used IT in information sharing and information quality to a great extent. For inter-organizational relationships, organizations rate commit-ment of supply chain partners as higher (3.75) compared with trust in supply chain partners (3.65) and shared vision between trading partners (3.60).

The IT enablers have the lowest mean among all the constructs and represent five e-business infrastructure solutions. A separate table (Table 4) is used to show the mean and standard deviation of each IT enablers. The

Table 2

Correlation matrix for independent variables

CU SU TU TMS IT TRU COM SV CU 1.00 SU 0.22⁎⁎ 1.00 TU 0.19⁎⁎ 0.16⁎ 1.00 TMS −0.05 −0.11 0.04 1.00 IT −0.15⁎ −0.17⁎ 0.22⁎ 0.07 1.00 TRU −0.08 −0.16 0.14 0.27⁎⁎ 0.11 1.00 COM −0.08 −0.22⁎ 0.08 0.22⁎⁎ 0.15⁎ 0.55⁎⁎ 1.00 SV −0.12 −0.09 0.10 0.38⁎⁎ 0.07 0.53⁎⁎ 0.57⁎⁎ 1.00 # of violation 0 2 1 0 0 0 0 0

CU:customer uncertainty, SU:supplier uncertainty, TU:technology uncertainty, TMS:top management support, IT:IT enablers, TRU:trust in supply chain partner, COM:commitment of supply chain partner, SV:shared vision between supply chain partner.

top three IT enablers used by organizations are Internet, intranet, and EDI, with a mean of 3.24, 3.18, 2.86 respectively, while the usage of EFT and extranet receives the less attention in the organization, indicated by their low means scores of 1.94 and 1.88 respectively. 4.2. Regression analysis of the factors impacting information sharing and information quality in SCM

To test the factors impacting information sharing and information quality, two linear regression analyses are conducted, using the eight influencing factors as independent variables and information sharing and information quality as dependent variable respectively. The results are shown inTable 5.

It can be seen that the level of information sharing and information quality is influenced positively by trust in supply chain partners and shared vision between supply chain partners, but negatively by supplier uncertainty. The higher the level of trust in supply chain partners and shared vision between supply chain partners and the lower the level of supplier uncertainty, the higher the level of information sharing and information quality. In one hand, the results indicate the importance of inter-organizational relationships in information sharing and information quality. On the other hand, the results reveal that a low level of supplier uncertainty is associated with high levels of information sharing and information quality. This can be true since

organizations may find it too risky to share information with suppliers with high uncertainty, such as unpredict-able engineering level, product quality and delivery time.

The results also show that top management support positively impact information sharing but has no significant impact on information quality. This finding is valuable. Without any doubt, top management support is important in initiating and implementing information sharing in SCM. Top management must understand the importance of information sharing in SCM and provide vision, guidance, and resources for its implementation. But top management may not be effective in ensuring the quality of shared information. A good inter-organizational relationship is needed in improving information quality in SCM.

Another finding from Table 5 is that information sharing and information quality is not influenced by customer uncertainty, technology uncertainty, commit-ment of supply chain partners, and IT enablers. 4.3. Discriminant analysis of organizations with high and low levels of information sharing

A discriminant analysis is used to explore the factors that contribute to the information sharing in SCM. Using discriminant analysis, a weighted liner combination of all the influencing factors is used to classify organizations into two groups: the high information sharing group and

Table 3

Descriptive statistics for influencing factors, information sharing and information quality

SCM practice Mean Std. deviation Information sharing 3.31 0.71 Information quality 3.33 0.63 Customer uncertainty 3.60 0.95 Supplier uncertainty 2.87 0.81 Technology uncertainty 3.59 0.84 Top management support 3.66 0.86

IT enablers 2.47 0.99

Trust in supply chain partners 3.65 0.63 Commitment of supply chain partners 3.75 0.57 Shared vision between supply chain partners 3.60 0.66

Table 4

Descriptive statistics for each IT enabler

IT enablers Mean Std. deviation

EDI 2.86 1.38 EFT 1.94 1.19 Internet 3.24 1.17 Intranet 3.18 1.49 Extranet 1.88 1.18 Table 5

Regression analysis of information sharing and information quality in SCM

Independent variables Dependent variables

IS IQ Standardized coefficients Sig. Standardized coefficients Sig. Customer uncertainty 0.027 0.670 −0.070 0.253 Supplier uncertainty −0.187 0.004 −0.142 0.023 Technology uncertainty 0.082 0.205 −0.072 0.249 Top management support 0.140 0.031 0.105 0.094 IT enablers 0.091 0.153 −0.064 0.300 Trust in supply chain

partners

0.204 0.008 0.240 0.001

Commitment of supply chain partners

0.116 0.142 0.126 0.100 Shared vision between

supply chain partners

0.178 0.026 0.254 0.001

R 0.58 0.153

R2 0.34 0.38

F-statistics 12.05 14.43

the low information sharing group. First, the mean of information sharing is calculated by summing up all the items of information sharing and divided it by the number of the items. The sample was then classified into the high and low information sharing group on the basis of high and low values for the information sharing compared to the sample mean for the information sharing.

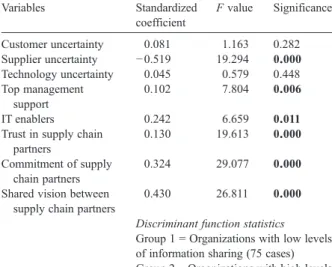

Table 6 presents the results of the discriminant analysis. The table provides information on (1) stan-dardized discriminant function coefficients and their significance, (2) the size of the group, and (3) the sig-nificance level of the discriminant function. The discri-minant function developed in this study has a chi-square value of 50.418 (8 degrees of freedom) which is significant at pb0.000 level. This provides strong support for the discriminate function's ability to discriminate group membership on the basis of the var-iables used. The results further show that all but two of the factors (customer uncertainty and technology uncer-tainty) are significant at the 0.01 level.

The standardized discriminant coefficients provide useful information on the relative contribution of their associated variables to the overall discriminate function. The high the absolute value of the standardized coefficient the greater is its contribution to the function. On this basis, supplier uncertainty emerges as the most important variable in its contribution to the discriminant function, followed by shared vision between supply chain partners, commitment of supply chain partners and IT enablers, in that order. Trust in trading partners and top management

support is less important. Table 7 presents, for each influencing factor, its mean value within each group and its overall mean. It can be seen that organizations with higher information sharing have a lower level of environmental uncertainty (in terms of customer, supplier, and technology uncertainty), a higher level of inter-organizational relationship (indicated by trust, commit-ment, shared vision) and a higher level of top management support and IT usage in their organizations.

To check further the informativeness of the model, the discriminant function's accuracy in classification was assessed. The classification results from the discri-minate model indicating a “hit rate” of 73.0%. This means that approximately 73.0% of the organizations were classified correctly by the discriminate model. This result further suggests that the influencing factors identified in this paper are able to successfully dis-tinguish between organizations having high levels of information sharing and those having low levels of information sharing.

Even though previous regression analyses reveal that commitment of supply chain partners and IT enablers do not significantly influence information sharing in SCM. But the discriminant analysis indicates both factors are significant in distinguishing between organizations with high levels of information sharing and those with low levels of information sharing.

4.4. Discriminant analysis of organizations with high and low levels of information quality

Again, a similar discriminant analysis is used to explore the factors that contribute to information quality in SCM.Table 8presents the results of the discriminant

Table 6

Discriminant analysis of organization with a high and low level of information sharing Variables Standardized coefficient Fvalue Significance Customer uncertainty 0.081 1.163 0.282 Supplier uncertainty −0.519 19.294 0.000 Technology uncertainty 0.045 0.579 0.448 Top management support 0.102 7.804 0.006 IT enablers 0.242 6.659 0.011

Trust in supply chain partners

0.130 19.613 0.000

Commitment of supply chain partners

0.324 29.077 0.000

Shared vision between supply chain partners

0.430 26.811 0.000

Discriminant function statistics Group 1 = Organizations with low levels of information sharing (75 cases) Group 2 = Organizations with high levels of information sharing (121 cases) Wilks' Lambda: 0.767, Chi-square: 50.418, significance: 0.000

Table 7

Group means of organization with a high and a low level of information sharing

Group means Low information sharing group High information sharing group Overall Customer uncertainty 3.69 3.54 3.60 Supplier uncertainty 3.17 2.68 2.87 Technology uncertainty 3.53 3.62 3.59 Top management support 3.45 3.80 3.66 IT enablers 2.24 2.61 2.47

Trust in supply chain partners

3.41 3.80 3.65

Commitment of supply chain partners

3.49 3.91 3.75

Shared vision between supply chain partners

analysis. The discriminant function has a chi-square value of 67.036 (8 degrees of freedom) which is significant atpb0.000 level. The results further show that all but two of the factors (technology uncertainty and IT enablers) are significant at the 0.05 level.Table 5also shows that shared vision between trading partners is the most important variable in its contribution to the discriminant function, followed by supplier uncertainty, commitment of supply chain partners and trust in supply chain partners, in that order. Customer uncertainty and top management support are less important. From Table 9, it can be seen that organizations with higher information quality have a lower level of environmental uncertainty (in terms of customer, supplier, and tech-nology uncertainty), a higher level of inter-organization-al relationship (indicated by trust, commitment, shared vision) and a higher level of top management support and IT usage in their organizations.

The classification accuracy of the discriminate model is 74.5%, suggesting that the influencing factors are able to successfully distinguish between organizations hav-ing high levels of information quality and those havhav-ing low levels of information quality.

Even though previous regression analyses indicate that information quality is not impacted by customer

uncertainty, top management support and commitment of trading partners, the discriminant analysis indicates those factors are significant in distinguishing between organizations with high levels of information quality and those with low levels of information quality.

In summary, supplier uncertainty, top management support, trust in supply chain partners, commitment of supply chain partners, and shared vision between supply chain partners are important in distinguishing between organizations with high levels of information sharing and information quality and those with low levels of information sharing and information quality. Among all the factors, supplier uncertainty, shared vision between supply chain partners and commitment of supply chain partners are three most important factors in their con-tribution to the discriminant function. It is also found that IT enablers are able to distinguish between organizations in terms of the level of information sharing, but not information quality. In contrast, customer uncertainty is able to distinguish between organization in terms of information quality, but not information sharing.

The study focuses on the impacts of independent variables (environmental uncertainty, inter-organization-al facilitators and inter-organizationinter-organization-al relationships) on dependent variables (information sharing and informa-tion quality) and ignores the possible relainforma-tionship bet-ween dependent variables. It is possible that there exists a strong association between information sharing and in-formation quality. A further analysis found that Pearson correlation between IS and IQ is 0.48 and significant at 0.0l level. A high level of information quality (repre-sented by timely and accurate information exchange) may encourage an organization to increase the level of information sharing with its supply chain partners.

Table 8

Discriminant analysis of organization with a high and low level of information quality Variables Standardized coefficient Fvalue Significance Customer uncertainty −0.095 4.359 0.038 Supplier uncertainty −0.421 18.551 0.000 Technology uncertainty −0.203 1.571 0.212 Top management support 0.030 7.647 0.006 IT enablers −0.176 0.002 0.968 Trust in supply chain

partners 0.292 31.800 0.000 Commitment of supply chain partners 0.334 39.486 0.000 Shared vision between supply chain partners 0.463 40.866 0.000

Discriminant function statistics

Group 1 = Organizations with low levels of information sharing (87 cases)

Group 2 = Organizations with high levels of information sharing (109 cases) Wilks' Lambda: 0.703, Chi-square: 67.036, significance: 0.000

Table 9

Group means of organization with a high and a low level of information quality

Group means Low information quality group High information quality group Overall Customer uncertainty 3.76 3.47 3.60 Supplier uncertainty 3.13 2.65 2.87 Technology uncertainty 3.67 3.52 3.59 Top management support 3.47 3.81 3.66 IT enablers 2.47 2.47 2.47

Trust in supply chain partners

3.39 3.86 3.65

Commitment of supply chain partners

3.49 3.96 3.75

Shared vision between supply chain partners

Likewise, increased information sharing activities will improve the quality of information by encouraging more complete and frequent information flow.

5. Conclusion and future research

The goal of this paper was to assess the antecedents of information sharing and information quality in SCM. Toward that goal, multiple theories from diverse referent disciples were synthesized to propose a research framework and six hypotheses were suggested (Fig. 1). The results partially support the hypotheses. It is found that information sharing is impacted positively by top management support, trust in supply chain partners and shared vision between supply chain partners, and negatively by supplier uncertainty. Those findings partially support 2.a1, 2.a2, and 3a. Moreover, we ini-tially hypothesized a positive relationship between environmental uncertainty and information sharing (Hypothesis 1a) but found a negative relationship between one of environmental uncertainty dimension (supplier uncertainty) and information sharing. The results also show that information quality is impacted by supplier uncertainty, trust in supply chain partners and shared vision between supply chain partners, which partially support Hypotheses 1b and 3b. Hypotheses 2.b1 and 2.b2 is disapproved since no significant relationship is found between intra-organizational facilitators and information quality. Moreover, a discriminant analysis reveals that supplier uncertainty, commitment of supply chain partners and shared vision between supply chain partners are the most important factors in discriminating between the organizations with high levels of informa-tion sharing and informainforma-tion quality and those with low levels of information sharing and information quality.

Generally, organizations with high levels of infor-mation sharing and inforinfor-mation quality are associated with low level of environmental uncertainty, high level of top management support and IT enablers, and high level of inter-organizational relationships. Furthermore, supplier uncertainty and inter-organizational relation-ships, instead of top management and IT enablers, are most critical factors in determining information sharing and information quality and in distinguishing organiza-tions with high levels of information sharing and information quality and those with low levels of information sharing and information quality.

The results of this study have the important im-plications for practitioners. First, both regression anal-ysis and discriminant analanal-ysis highlight the importance of inter-organizational relationships (build on trust, commitment and shared vision) in facilitating

informa-tion sharing and informainforma-tion quality. Frequently, organi-zations have tended to focus on the applications of IT on SCM, they have not given enough attention to the de-velopment of inter-organizational relationships. This phenomenon may reflect the nature of IT and inter-organizational relationships. Compared with inter-orga-nizational relationships, IT can be more easily imple-mented, and its benefits are more tangible and meazsurable. While the establishment of good inter-organizational relationships (such as trust, commitment, and shared vision) is much more difficult and time-consuming than the installation of SCM software, its impact on overall performance is mostly invisible. The results of this study demonstrate to the practitioners that to achieve higher levels of information sharing and information quality, an effective inter-organizational relationship is a must. Therefore, it would be worthwhile for organizations that are contemplating sharing infor-mation to spend time and effort to build good relation-ships with their supply chain partners. Second, the findings indicate a low level of supplier uncertainty is associated with high level of information sharing and information quality. To ensure quality information sha-ring, an organization must select its suppliers with caution.

It should be noted that information sharing and information quality may be influenced by contextual factors, such as the type of industry, firm size, a firm's position in the supply chain, supply chain length, and type of supply chain, which are ignored in this study. For example, the larger organizations may have higher levels of information sharing since they usually have more complex supply chain networks necessitating the need for more frequent and effective information ex-change with its partners . The level of information quality may be influenced negatively by the length of a supply chain. Since information suffers from delay and distortion as it travels along the supply chain, the shorter the supply chain, the less chances it will get distorted. Future research can expand this research by adding the contextual factors as an additional independent variable. This study indicates that partner relationship plays an important role in implementing SCM practice and improving SCM performance. There are several issues regarding the establishment of good partner relation-ship (such as trust, commitment, and shared vision). For example, how does one get trading partners to trust each other? What tools and procedures can be used to establish a shared vision between trading partners? What skills are necessary to develop commitment and credibility in the relationship of trading partners? How should an organization identify

channel partners who participate in trust-creating behaviors? What is the role of channel conflict in partner relationship? There are to be addressed in future research. The future study can also expand the model by considering the independence between information sharing and information quality. More-over, the data for the study consisted of responses from single respondents in an organization which may be a cause for possible response bias. The results have to be interpreted taking this limitation into account. The use of single respondent may generate some measurement inaccuracy. Future research should seek to utilize multiple respondents from each participating organization to enhance the research findings.

This study suffers from methodological limitations typical of most empirical surveys. First, this study employed only several possible theoretical lenses that can explain causal relationships among the antecedents of information sharing and information quality. Appli-cation of any theory to a research problem automatically places constraints on variables, relationships, assump-tions, and boundary conditions that can be examined, which may lead to a biased interpretation of the problem in practice. Second, our survey constructs do not consider future potential value in information sharing and information quality. The incorporate future potential value of information sharing and information quality, panel information is needed which was not available. In future research, a longitudinal research can be developed.

Appendix A. Items for environmental uncertainty, intra-organizational facilitators,

inter-organizational relationships⁎

⁎All the items for each construct except IT enablers are measured on a 1–5 Likert scale from “Strongly Disagree”to“Strongly Agree”. The items for IT enablers are measured based on a 1–5 Likert scale from“Not at all”to“To a great extent”

Information sharing and information quality Information sharing(α= 0.72)

We inform trading partners in advance of changing needs.

Our trading partners share proprietary infor-mation with us.

Our trading partners share business knowledge of core business processes with us.

Information quality(α= 0.86)

Information exchange between our trading partners and us is timely.

Information exchange between our trading partners and us is accurate.

Information exchange between our trading partners and us is complete.

Information exchange between our trading partners and us is adequate.

Information exchange between our trading partners and us is reliable.

Environmental uncertainty Customer uncertainty(α= 0.79)

Customers order different product combina-tions over the year.

Customers' product preferences change over the year.

Supplier uncertainty(α= 0.81)

The properties of materials from suppliers can vary greatly within the same batch.

Suppliers' engineering level is unpredictable. Suppliers' product quality is unpredictable. Suppliers' delivery time can easily go wrong. Technology uncertainty(α= 0.82)

Technological changes provide opportunities for enhancing competitive advantage in our industry.

Technological breakthrough results in many new product ideas in our industry.

Improving technology generates new products frequently in our industry.

Top management support and IT enablers Top management support(α= 0.90)

Top management considers the relationship bet-ween us and our trading partners to be important. Top management supports SCM with the resources we need.

Top management regards SCM as a high priority item.

Top management participates in SCM and its optimization.

IT enablers(α= 0.74)

The extent of usage of EDI in your firm. The extent of usage of EFT in your firm. The extent of usage of Internet in your firm. The extent of usage of Intranet in your firm. The extent of usage of Extranet in your firm.. Inter-organizational relationships

Trust in trading partners(α= 0.80)

Our trading partners have been open and honest in dealing with us.

Our trading partners respect the confidentiality of the information they receive from us. Our transactions with trading partners do not have to be closely supervised

Commitment of trading partners(α= 0.78) Our trading partners have made sacrifices for us in the past.

We have invested a lot of effort in our rela-tionship with trading partners.

Our trading partners abide by agreements very well.

We and our trading partners always try to keep each others' promises.

Shared vision between trading partners(α= 0.85) We and our trading partners have a similar understanding about the aims and objectives of the supply chain.

We and our trading partners have a similar understanding about the importance of collab-oration across the supply chain.

We and our trading partners have a similar understanding about the importance of improvements that benefit the supply chain as a whole.

References

[1] R.S. Achrol, L.K. Scheer, L.W. Stern, Designing Successful Trans-Organizational Marketing Alliances, Report, vol. 90-118, Marketing Science Institute, Cambridge, MA, 1990.

[2] D. Alvarez, Solving the puzzle of industry's rubic cube-effective supply chain management, Logistics Focus 2 (4) (1994) 2–4. [4] R.H. Ballou, S.M. Gillbert, A. Mukherjee, New managerial

challenge from supply chain opportunities, Industrial Marketing Management 29 (2000) 7–18.

[5] P.W. Balsmeier, W. Voisin, Supply chain management: a time-based strategy, Industrial Management 38 (5) (1996) 24–27. [6] D. Berry, D.R. Towill, N. Wadsley, Supply chain management in

the electronics products industry, International Journal of Physical Distribution and Logistics Management 24 (10) (1994) 20–32. [7] D. Boddy, D. MacBeth, B. Wagner, Implementing collaboration

between organizations: an empirical study of supply chain part-nering, Journal of Management Studies 37 (7) (2000) 1003–1017.

[8] L.P. Bucklin, S. Sengupta, Organizing successful co-marketing alliances, Journal of Marketing 57 (April 1993) 32–46. [9] R. Burgess, Avoiding supply chain management failure: lessons

from business process re-engineering, International Journal of Logistics Management 9 (1) (1998) 15–23.

[10] G.P. Cachon, M. Fisher, Supply chain inventory management and the value of shared information, Management Science 46 (8) (2000) 1032–1048.

[11] C. Chandra, S. Kumar, Supply chain management in theory and practice: a passing fad or a fundamental change, Industrial Management and Data Systems 100 (3) (2000) 100–113. [12] P. Childhouse, D.R. Towill, Simplified material flow holds

the key to supply chain integration, OMEGA 31 (1) (2003) 17–27.

[13] S.A. Chizzo, Supply chain strategies: solutions for the customer-driven enterprise, Software Magazine, Supply Chain Manage-ment Directions SuppleManage-ment (January 1998) 4–9.

[14] T.H. Clark, H.G. Lee, Performance, interdependence and coordi-nation in business-to-business electronic commerce and supply chain management, Information Technology and Management 1 (2000) 85–105.

[15] J.E. Ettlie, E.M. Reza, Organizational integration and process innovation, Academy of Management Journal 35 (4) (1992) 795–827.

[16] G.N. Evans, M.M. Naim, D.R. Towill, Dynamic supply chain performance: assessing the impact of information systems, Lo-gistics Information Management 6 (4) (1993) 15–25.

[17] M. Feldmann, S. Mrller, An incentive scheme for true informa-tion providing in supply chains, OMEGA 31 (2) (2003) 63–73. [18] V. Grover, An empirically derived model for the adoption of customer-based inter-organizational systems, Decision Sciences 24 (3) (1993) 603–639.

[19] A.K. Gupta, D.L. Wilemon, Accelerating the development of technology-based new products, California Management Review 32 (2) (1990) 24–44.

[20] G.D. Hamel, C.K. Prahalad, Collaborate with your competitors and win, Harvard Business Review (January–February 1989). [21] R.B. Handfield, E.L. Nichols Jr., Introduction to Supply Chain

Management, Prentice Hall, Upper Saddler River, New Jersey, 1999.

[22] S. Holmberg, A systems perspective on supply chain measure-ments, International Journal of Physical Distribution and Logistics Management 30 (10) (2000) 847–868.

[23] P.K. Humphreys, M.K. Lai, D. Sculli, An inter-organizational information system for supply chain management, International Journal of Production Economics 70 (2001) 245–255. [24] J.L. Jarrell, Supply chain economics, World Trade 11 (11) (1998)

58–61.

[25] C. Jones, Moving beyond ERP: making the missing link, Logistics Focus 6 (7) (1998) 2–7.

[26] D.R. Krause, R.B. Handfield, T.V. Scannel, An empirical investi-gation of supplier development: reactive and strategic processes, Journal of Operations Management 17 (1) (1998) 39–58. [27] B.J. Lalonde, Building a supply chain relationship, Supply Chain

Management Review 2 (2) (1998) 7–8.

[28] C.J. Lambe, R.E. Spekman, Alliances, external technology acquisition and discontinuous technological change, Journal of Product Innovation Management 14 (2) (1997) 102–116. [29] H. Lee, C. Billington, Managing supply chain inventories:

pit-falls and opportunities, Sloan Management Review 33 (3) (1992) 65–73.

[30] J. Lee, Y. Kim, Effect of partnership quality on IS outsourcing: conceptual framework and empirical validation, Journal of Management Information Systems 15 (4) (1999) 26–61. [32] D. Lim, P.C. Palvia, EDI in strategic supply chain: impact on

customer service, International Journal of Information Manage-ment 21 (2001) 193–211.

[33] F. Lin, S. Huang, S. Lin, Effects of information sharing on supply chain performance in electronic commerce, IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management 49 (3) (2002) 258–268.

[34] J. Magretta, The power of virtual integration: an interview with Dell computers' Michael Dell, Harvard Business Review 76 (2) (1998) 72–84.

[35] R. Mason-Jones, D.R. Towill, Information enrichment: designing the supply chain for competitive advantage, Supply Chain Management 2 (4) (1997) 137–148.

[36] J.T. Mentzer, S. Min, Z.G. Zacharia, The nature of interfirm partnering in supply chain management, Journal of Retailing 76 (4) (2000) 549–568.

[37] C.R. Moberg, B.D. Cutler, A. Gross, T.W. Speh, Identifying antecedents of information exchange within supply chains, International Journal of Physical Distribution and Logistics Management 32 (9) (2002) 755–770.

[38] R.M. Monczka, K.J. Petersen, R.B. Handfield, G.L. Ragatz, Success factors in strategic supplier alliances: the buying company perspective, Decision Science 29 (3) (1998) 5553–5577.

[39] D. Noble, Purchasing and supplier management as a future competitive edge, Logistics Focus 5 (5) (1997) 23–27. [40] J.C. Nunnally, Psychometric Theory, McGraw-Hill, New York,

1978.

[41] D.J. Power, A. Sohal, S.U. Rahman, Critical success factors in agile supply chain management: an empirical study, International Journal of Physical Distribution and Logistics Management 31 (4) (2001) 247–265.

[42] S. Prasad, J. Tata, Information investment in supply chain management, Logistics Information Management 13 (1) (2000) 33–38.

[43] S. Reda, Internet-EDI initiatives show potential to reinvent supply chain management, Stores 81 (1) (1999) 26–27. [44] Z. Rahman, Use of Internet in supply chain management: a study

of Indian companies, Industrial Management and Data Systems 104 (1) (2004) 31–41.

[45] P.H. Schurr, J.L. Ozanne, Influences on exchange processes: buyers' preconceptions of a seller's trustworthiness and bargain-ing toughness, Journal of Consumer Research 11 (4) (1985) 939–953.

[46] J. Sheridan, Bonds of trust, Industry Week 246 (6) (1997) 52–62. [47] J.H. Sheridan, The supply-chain paradox, Industry Week 247 (3)

(1998) 20–29.

[48] R.E. Spekman, J.W. Kamauff, N. Myhr, An empirical investigation into supply chain management: a perspective on partnerships, Supply Chain Management 3 (2) (1998) 53–67.

[49] T. Stein, J. Sweat, Killer supply chains, InformationWeek 708 (9) (1998) 36–46.

[50] K.C. Tan, V.R. Kannan, R.B. Handfield, Supply chain manage-ment: supplier performance and firm performance, International Journal of Purchasing and Materials Management 34 (3) (1998) 2–9.

[51] K.C. Tan, S.B. Lyman, J.D. Wisner, Supply chain management: a strategic perspective, International Journal of Operations and Production Management 22 (6) (2002) 614–631.

[52] L. Tattum, Staying at the cutting edge of supply chain practice, Chemical Week 161 (11) (1999) s10–s12.

[53] D. Thomas, P.M. Griffin, Coordinated supply chain management, European Journal of Operational Research 94 (1) (1996) 1–15. [54] D.R. Towill, The seamless chain the predator's strategic

advantage, International Journal of Technology Management 13 (1) (1997) 37–56.

[55] J.R. Turner, Integrated supply chain management: what's wrong with this picture, Industrial Engineering 25 (12) (1993) 52–55. [56] R.I. Van Hoek, Postponement and the reconfiguration challenge

for food supply chains, Supply Chain Management 4 (1) (1999) 18–34.

[57] L.W. Walton, Partnership satisfaction: using the underlying dimensions of supply chain partnership to measure current and expected levels of satisfaction, Journal of Business Logistics 17 (2) (1996) 57–75.

[58] A.G. White. Supply chain link up manufacturing systems. 14 (10) (1996) 94–98.

[59] D.T. Wilson, R.P. Vlosky, Inter-organizational information system technology and buyer–seller relationships, Journal of Business and Industrial Marketing 13 (3) (1998) 215–234. [60] W.Y. Wu, C.Y. Chiag, Y.F. Wu, H.F. Tu, The influencing factors

of commitment and business integration on supply chain management, Industrial Management and Data Systems 104 (4) (2004) 322–333.

[61] D. Young, H.H. Carr, R.K. Rainer, Strategic implications of electronic linkages, Information Systems Management (Winter 1999) 32–39.

[62] Z.X. Yu, H. Yan, T.C.E. Cheng, Benefits of information sharing with supply chain partnerships, Industrial Management and Data Systems 101 (3) (2001) 114–119.

[63] X. Zhao, J. Xie, W.J. Zhang, The impact of information sharing and order-coordination on supply chain performance, Supply Chain Management: an International Journal 7 (1) (2002) 24–40.

Dr. Suhong Li is assistant profes-sor of Computer Information Sys-tems at Bryant University. She earned her PhD from the Univer-sity of Toledo in 2002. She has published in academic journals includingJournal of Operations Management, OMEGA:the Inter-national Journal of Management Science, Journal of Computer Information Systems and Interna-tional Journal of Integrated Sup-ply Management. Her research interests include supply chain management, electronic commerce, and adoption and implementa-tion of IT innovaimplementa-tion.

Dr. Binshan Lin is the BellSouth Corporation Professor at College of Business Administration, Louisiana State University in Shreveport. He received his Ph. D. from the Louisiana State Uni-versity in 1988. He is a seven-time recipient of the Outstanding Faculty Award at LSUS. Dr. Lin receives the Computer Educator of the Year by the International Association for Computer Infor-mation Systems (IACIS) in 2005, Ben Bauman Award for Excellence in IACIS 2003, Outstanding Educator Award by the Southwest Decision Sciences Institute (SWDSI) in 2004, and Emerald Literati Club Awards for Excellence in 2003. He has published over 140 articles in refereed journals, and currently serves as Editor-in-Chief of the following nine academic journals:Industrial Management and Data Systems,International Journal of Mobile Communications, International Journal of Innovation and Learning, International Journal of Management and Enterprise Development, Electronic Government:An Interna-tional Journal, InternaInterna-tional Journal of Electronic Healthcare, International Journal of Service and Standards, International Journal of Electronic Finance,andInternational Journal of Manage-ment in Education.