original article

Early Treatment with Prednisolone

or Acyclovir in Bell’s Palsy

Frank M. Sullivan, Ph.D., Iain R.C. Swan, M.D., Peter T. Donnan, Ph.D., Jillian M. Morrison, Ph.D., Blair H. Smith, M.D., Brian McKinstry, M.D., Richard J. Davenport, D.M., Luke D. Vale, Ph.D., Janet E. Clarkson, Ph.D.,

Victoria Hammersley, B.Sc., Sima Hayavi, Ph.D., Anne McAteer, M.Sc., Ken Stewart, M.D., and Fergus Daly, Ph.D.

From the Scottish School of Primary Care (F.M.S.), Community Health Sciences (P.T.D., F.D.), and Dental Health Servic es Research Unit (J.E.C.), University of Dundee, Dundee; the Department of Oto laryngology (I.R.C.S.) and the Division of Community Based Sciences (J.M.M., S.H.), University of Glasgow, Glasgow; the De partment of General Practice and Primary Care (B.H.S., A.M.) and the Health Eco nomics Research Unit (L.D.V.), Univer sity of Aberdeen, Aberdeen; Community Health Sciences (B.M., V.H.) and the Department of Clinical Neurosciences (R.J.D.), University of Edinburgh, Edin burgh; and St. John’s Hospital, National Health Service Lothian, Livingston (K.S.) — all in the United Kingdom. Address re print requests to Dr. Sullivan at the Scot tish School of Primary Care, Mackenzie Bldg., University of Dundee, Kirsty Semple Way, Dundee DD2 4BF, United Kingdom, or at f.m.sullivan@chs.dundee.ac.uk. N Engl J Med 2007;357:1598607. Copyright © 2007 Massachusetts Medical Society.

Abs tr act Background

Corticosteroids and antiviral agents are widely used to treat the early stages of idio-pathic facial paralysis (i.e., Bell’s palsy), but their effectiveness is uncertain. Methods

We conducted a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized, factorial trial involv-ing patients with Bell’s palsy who were recruited within 72 hours after the onset of symptoms. Patients were randomly assigned to receive 10 days of treatment with pred-nisolone, acyclovir, both agents, or placebo. The primary outcome was recovery of facial function, as rated on the House–Brackmann scale. Secondary outcomes included qual-ity of life, appearance, and pain.

Results

Final outcomes were assessed for 496 of 551 patients who underwent randomization. At 3 months, the proportions of patients who had recovered facial function were 83.0% in the prednisolone group as compared with 63.6% among patients who did not receive prednisolone (P<0.001) and 71.2% in the acyclovir group as compared with 75.7% among patients who did not receive acyclovir (adjusted P = 0.50). After 9 months, these proportions were 94.4% for prednisolone and 81.6% for no pred-nisolone (P<0.001) and 85.4% for acyclovir and 90.8% for no acyclovir (adjusted P = 0.10). For patients treated with both drugs, the proportions were 79.7% at 3 months (P<0.001) and 92.7% at 9 months (P<0.001). There were no clinically significant dif-ferences between the treatment groups in secondary outcomes. There were no seri-ous adverse events in any group.

Conclusions

In patients with Bell’s palsy, early treatment with prednisolone significantly improves the chances of complete recovery at 3 and 9 months. There is no evidence of a benefit of acyclovir given alone or an additional benefit of acyclovir in combination with pred-nisolone. (Current Controlled Trials number, ISRCTN71548196.)

n engl j med 357;16 www.nejm.org october 18, 2007 1599

B

ell’s palsy is acute, idiopathic,uni-lateral paralysis of the facial nerve.1

Vascu-lar, inflammatory, and viral causes have been suggested from paired serologic analyses and studies of the cerebral ganglia, suggesting an as-sociation between herpes infection and the onset

of facial paralysis.2-4 Epidemiologic studies show

that 11 to 40 persons per 100,000 are affected each year, most commonly between the ages of 30

and 45 years.5 Although most patients recover well,

up to 30% of patients have a poor recovery, with continuing facial disfigurement, psychological

dif-ficulties, and facial pain.6,7 Treatment remains

con-troversial and variable.8 Prednisolone and

acyclo-vir are commonly prescribed separately and in combination, although evidence of their

effective-ness is weak.9,10

Two recent Cochrane reviews assessed the ef-fectiveness of corticosteroids and antiviral agents in patients with Bell’s palsy. The analysis of cor-ticosteroid treatment pooled the results of four randomized, controlled trials with a total of 179

patients.11 The review of antiviral treatment

in-cluded three studies involving 246 patients.12 Both

reviews independently concluded that insufficient data exist to support the use of either or both therapies.

Given this lack of evidence, the Health Technol-ogy Assessment Program of the National Institute for Health Research commissioned an indepen-dent academic group to determine whether pred-nisolone or acyclovir used early in the course of

Bell’s palsy improves the chances of recovery.13

Methods

Patients

We established receiving centers at 17 hospitals throughout Scotland, to which potential patients with Bell’s palsy were referred. Eligible patients with a confirmed diagnosis who consented to join the study were randomly assigned to study groups and were followed for 9 months. Complete details of the study design and the analysis plan have been

published previously.14 The complete study

pro-tocol appears in the Supplementary Appendix, available with the full text of this article at www. nejm.org.

We recruited adults 16 years of age or older with unilateral facial-nerve weakness of no identifiable cause who presented to primary care or the emer-gency department and could be referred to a

col-laborating otorhinolaryngologist within 72 hours after the onset of symptoms. Exclusion criteria were pregnancy, breast-feeding, uncontrolled diabetes (glycated hemoglobin level, >8%), peptic ulcer disease, suppurative otitis media, herpes zoster, multiple sclerosis, systemic infection, sarcoidosis and other rare conditions, and an inability to pro-vide informed consent.

All patients provided written informed consent after the aims and methods of the study had been described to them and after they had received an information sheet. The study was approved by the Multicenter Research Ethics Committee for Scot-land and was conducted in accordance with the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice guidelines. Drugs (including pla-cebo) were purchased from Tayside Pharmaceu-ticals, an organization that manufactures special medicines for the National Health Service in Scot-land and for commercial customers.

Study Design

From June 2004 to June 2006, we conducted a two-by-two factorial study across the whole of mainland Scotland (total population, 5.1 million), with re-ferrals mainly from primary care to 17 hospitals serving 88% of the country’s total population. Fol-low-up was continued until March 2007, when the last patients to be recruited underwent their 9-month assessments. Patients were recruited through their family doctors, emergency depart-ments, the national 24-hour medical telephone consultancy service, and dentists’ offices. Patients, recruiters, study visitors, and outcome assessors were all unaware of study-group assignments.

As soon as the senior otorhinolaryngologist who had been trained in the study procedures at the trial site confirmed a patient’s eligibility to participate and consent was obtained, the pa-tient was randomly assigned to a study group by an independent, secure, automated telephone-ran-domization service provided by the University of

Aberdeen’s Health Services Research Unit.15

Ran-domization was performed with the use of a per-muted-block technique, with block sizes of four or eight and no stratification. Patients were in-structed to take the first dose of the study drug before leaving the hospital and the remaining doses at home during the next 10 days.

Patients underwent randomization twice, which resulted in four study groups that each received two preparations: prednisolone (at a dose of 25 mg

Copyright © 2007 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved. Downloaded from www.nejm.org by DANIEL OLAUGHLIN MD on October 18, 2007 .

twice daily) and placebo (lactose), acyclovir (400 mg five times daily) and placebo, prednisolone and acyclovir, and two placebo capsules. Tayside Phar-maceuticals managed the preparation of active and placebo ingredients in cellulose capsules and the drug bottling, labeling, and distribution to clini-cal sites. Only Tayside Pharmaceuticlini-cals and the 17 hospital pharmacies had access to the codes. Thus, each patient received two bottles of odorless cap-sules with an identical appearance.

Within 3 to 5 days after randomization, a re-searcher visited patients at home or, if preferred, at a doctor’s office to complete a baseline assess-ment. Repeat visits to assess recovery occurred at 3 months. If recovery was incomplete (which was defined as grade 2 or more on the House–Brack-mann scale) at this visit, the visit was repeated at 9 months. Researchers analyzed clinical records for 15% of patients to validate primary care and hospital-consultation data, toxic effects, and coex-isting illnesses after the final visit. An independent data and safety monitoring committee performed a review 14 months after recruitment began. Outcome Measurements

The primary outcome measure was the House– Brackmann grading system for facial-nerve

func-tion (see the Supplementary Appendix),16 an easily

administered, widely used clinical system for grad-ing recovery from facial-nerve paralysis caused by damage to lower motor neurons. The scoring sys-tem assigns patients to one of six categories on the basis of the degree of facial-nerve function, with grade 1 indicating normal function. The primary outcome was assessed by documenting the facial appearance of patients in digital photographic im-ages in four standard poses: at rest, with a forced smile, with raised eyebrows, and with eyes tightly closed. (Images of a patient at enrollment are avail-able in the Supplementary Appendix.) The photo-graphs were assessed and graded independently by a panel of three experts — an otorhinolaryn-gologist, a neurologist, and a plastic surgeon — who were unaware of study-group assignments and the stage of assessment. Ninety-two percent of the panel members’ assessments differed by no more than one House–Brackmann grade. Discrepancies of more than one grade were reassessed. The me-dian of the three grades provided a final determi-nation.

Secondary outcomes were health-related qual-ity of life, as measured with the Health Utilities

Index Mark 3; facial appearance, as measured with the Derriford Appearance Scale 59; and pain, as measured with the Brief Pain Inventory. The Health Utilities Index Mark 3 provides a system for the classification of health-related quality of life status in eight dimensions: vision, hearing, speech, ambulation, dexterity, emotion, cognition, and pain, with five or six levels of severity per dimen-sion. A preference-based scoring system is used, and responses are commonly converted into a single score ranging from –0.36 to 1.00, with 1 indicating full health; a negative score indicates a quality of life that is considered by the patient to be worse than death. The questionnaire is de-signed for use in clinical practice and research, health policy evaluation, and general population

surveys.17 The Derriford Appearance Scale

con-tains 59 questions covering aspects of self-con-sciousness and confidence, with scores ranging from 8 to 262 and higher scores indicating a

greater severity of distress and dysfunction.18 The

Brief Pain Inventory measures both the severity of pain and the extent to which pain interferes with normal activities; scores range from 0 to 110, with

higher scores indicating greater severity.19

Adverse Events

Adverse events were reviewed at each study visit. Compliance with the drug regimen was reviewed at the first visit and during telephone calls on day 7 after randomization and within a week after the final day of the study (10 days after randomiza-tion). Patients were instructed to return pill con-tainers and any unused capsules in the container to the study center at the University of Dundee. Statistical Analysis

All analyses were based on the intention-to-treat principle, and specific comparisons were prespec-ified in the protocol. We initially tested the data for any interaction among study groups. If the results were not significant, we compared the primary out-come measure of complete recovery (grade 1 on the House–Brackmann scale) at 3 months and 9 months between patients who did and those who did not receive prednisolone, using a two-sided Fisher’s ex-act test. We repeated this procedure for acyclovir. In addition, we then compared prednisolone with placebo, acyclovir with placebo, and the combina-tion of the two drugs with placebo. Prespecified secondary analyses compared scores on quality of life, facial appearance, and pain with the use of

n engl j med 357;16 www.nejm.org october 18, 2007 1601 t-tests or Mann–Whitney tests in cases in which

the data were not normally distributed. Then we used logistic regression to adjust the analysis for all baseline characteristics that we measured: age, sex, the time from the onset of symptoms to the initiation of treatment, scores on the House–Brack-mann scale, and scores for quality of life, appear-ance, and pain. The significance of baseline fac-tors was assessed with the use of Wald tests, with a P value of less than 0.05 considered to indicate statistical significance.

The results were also assessed for sensitivity to

dropout, assuming that the dropouts were miss-ing at random. A propensity score for dropout at 9 months was estimated with the use of logistic regression, and a further analysis was carried out to weight results according to the reciprocal of the

probability of remaining in the study.20

The relevant Cochrane reviews suggested that 32 to 37% of patients with Bell’s palsy have in-complete recovery without treatment and that this percentage can be reduced to 22% with effective treatment. A between-group difference in the com-plete-recovery rate of at least 10 to 12 percentage

33p9 551 Underwent randomization

752 Patients were screened

201 Were excluded

132 Did not meet inclusion criteria 59 Declined to participate

6 Had enrollment error 4 Received active treatment

272 Were assigned to receive acyclovir

134 Were assigned to receive prednisolone

130 Received prednisolone 4 Received incorrect drug

138 Were assigned to receive placebo

135 Received placebo 3 Received incorrect drug

138 Were assigned to receive prednisolone

135 Received prednisolone 3 Received incorrect drug

141 Were assigned to receive placebo

141 Received placebo 279 Were assigned to

receive placebo

Acyclovir plus prednisolone Acyclovir plus placebo Placebo plus prednisolone Placebo plus placebo

AUTHOR: FIGURE: JOB: ISSUE: 4-C H/T RETAKE SIZE ICM CASE EMail Line H/T Combo Revised

AUTHOR, PLEASE NOTE:

Figure has been redrawn and type has been reset. Please check carefully.

REG F Enon 1st 2nd 3rd Sullivan 1 of 2 10-18-07 ARTIST: ts 35716 124 Completed therapy

10 Were lost to follow-up 2 Withdrew consent 2 Sought active

treat-ment

6 Could not be contacted after first visit

123 Completed therapy 15 Were lost to follow-up

1 Could not be contacted 2 Withdrew consent 1 Sought active

treat-ment

1 Was withdrawn by investigator

9 Could not be contacted after first visit 1 Died

127 Completed therapy 11 Were lost to follow-up

4 Withdrew consent 2 Sought active

treat-ment

1 Did not provide primary-outcome data 4 Could not be contacted

after first visit

122 Completed therapy 19 Were lost to follow-up

3 Could not be contacted 6 Withdrew consent 3 Sought active

treat-ment

1 Was withdrawn by investigator

1 Did not provide primary-outcome data 3 Could not be contacted

after first visit 2 Died

Figure 1. Enrollment and Outcomes.

Copyright © 2007 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved. Downloaded from www.nejm.org by DANIEL OLAUGHLIN MD on October 18, 2007 .

points was considered to be clinically meaning-ful. The randomization of 236 patients per treat-ment (a total of 472 patients) provided a power of 80% to detect such a difference. Since the study design was factorial, the power was the same for each pairwise comparison of treatments (assum-ing there was no interaction between treatments).

R esults

Study Population

Of 752 patients who were referred for participation in the study, 132 were found to be ineligible; of the remaining 620 patients, 551 (88.9%) underwent randomization. Of these patients, 415 had been referred by their family doctor (75.3%) and 41 by an emergency department (7.4%). Since 55 patients dropped out of the study before a final determi-nation of the House–Brackmann grade, a final outcome was available for 496 patients (90.0%) (Fig. 1).

The patients were equally divided between men and women, the mean (±SD) age was 44.0±16.4

years, and the degree of initial facial paralysis was moderate to severe (Table 1). After the onset of symptoms, most patients (53.8%) initiated treat-ment within 24 hours, 32.1% within 48 hours, and 14.1% within 72 hours. A total of 426 patients (86%) returned pill containers; of these patients, 383 (90%) returned empty containers, indicating complete compliance, 32 (8%) returned doses for 5 days or less, and 11 patients (3%) returned doses for 6 days or more.

There was no significant interaction between prednisolone and acyclovir at either 3 months or 9 months (P = 0.32 and P = 0.72, respectively). Ta-ble 2 presents the adjusted outcome data for the 496 patients who completed the study. Of these patients, 357 had recovered by 3 months and did not require a further visit. Of the remainder, 80 had recovered at 9 months, leaving 59 with a re-sidual facial-nerve deficit.

At 3 months, rates of complete recovery dif-fered significantly between the prednisolone com-parison groups: 83.0% for patients who received prednisolone and 63.6% for those who did not,

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of the Patients.*

Characteristic Prednisolone(N = 251) No Prednisolone(N = 245) Acyclovir(N = 247) No Acyclovir(N = 249) (N = 496)Total

Sex — no. (%)

Male 135 (53.8) 118 (48.2) 119 (48.2) 134 (53.8) 253 (51.0) Female 116 (46.2) 127 (51.8) 128 (51.8) 115 (46.2) 243 (49.0) Age — yr 43.2±16.2 44.9±16.6 45.0±16.6 43.0±16.1 44.0±16.4 Score on House–Brackmann scale† 3.5±1.2 3.8±1.3 3.6±1.3 3.7±1.2 3.6±1.3 Score on Health Utilities Index Mark 3‡ 0.80±0.22 0.78±0.21 0.79±0.21 0.78±0.22 0.79±0.22 Score on Derriford Appearance Scale 59§ 71±37 75±41 72±39 74±38 73±39 Score on Brief Pain Inventory¶ 10±18 16±21 12±18 14±21 13±20 Time between onset of symptoms and

start of treatment — no. (%)

Within 24 hr 120 (47.8) 147 (60.0) 137 (55.5) 130 (52.2) 267 (53.8) >24 to ≤48 hr 95 (37.8) 64 (26.1) 75 (30.4) 84 (33.7) 159 (32.1) >48 to ≤72 hr 25 (10.0) 18 (7.3) 25 (10.1) 18 (7.2) 43 (8.7) Unknown (but ≤72 hr) 11 (4.4) 16 (6.5) 10 (4.0) 17 (6.8) 27 (5.4) * Plus–minus values are means ±SD. The subcategories listed in the four columns match the analysis presented in Table 2 rather than that of

the study groups discussed in the text and represented in the figures. Data for the four study groups are available in the Supplementary Appendix. Percentages may not total 100 because of rounding.

† Data are missing for 12 patients on the House–Brackmann scale, which ranges from 1 to 6, with higher grades indicating worse facial paralysis.

‡ Data are missing for 13 patients on the Health Utilities Index Mark 3, which ranges from –0.36 to 1.00 (as assessed by the patient), with 1 indicating full health; negative scores indicate a quality of life that is considered worse than death.

§ Data are missing for 13 patients on the Derriford Appearance Scale 59, which ranges from 8 to 262, with higher scores indicating more dis tress and dysfunction.

n engl j med 357;16 www.nejm.org october 18, 2007 1603 Ta bl e 2. Primary and Secondary Outcomes at 3 Months and 9 Months.* Variable Prednisolone (N = 251) No Prednisolone (N = 245) Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI) P Value Acyclovir (N = 247) No Acyclovir (N = 249) Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI) P Value No./Total No. (%) No./Total No. (%) Primary outcome measure† Grade 1 on House–Brackmann scale‡ At 3 mo 205/247 (83.0) 152/239 (63.6) 2.44 (1.55–3.84) <0.001 173/243 (71.2) 184/243 (75.7) 0.86 (0.55–1.34) 0.50 At 9 mo 237/251 (94.4) 200/245 (81.6) 3.32 (1.72–6.44) <0.001 211/247 (85.4) 226/249 (90.8) 0.61 (0.33–1.11) 0.10 Unadjusted Mean Adjusted Beta§ Unadjusted Mean Adjusted Beta§ Secondary outcome measures¶ Score on Health Utilities Index Mark 3‖ At 3 mo 0.91±0.17 0.91±0.13 −0.01±0.01 0.40 0.90±0.16 0.92±0.14 −0.01±0.01 0.32 At 9 mo 0.84±0.26 0.88±0.16 −0.06±0.03 0.04 0.86±0.21 0.88±0.19 −0.02±0.03 0.38 Score on Brief Pain Inventory** At 3 mo 1.51±6.41 2.04±8.14 −0.12±0.67 0.85 1.83±7.00 1.72±7.62 0.13±0.66 0.84 At 9 mo 1.36±5.29 1.83±6.37 −0.08±1.02 0.94 1.61±5.87 1.72±6.19 0.05±0.96 0.96 Score on Derriford Appearance Scale 59†† At 3 mo 42.4±32.3 43.2±33.4 1.72±2.88 0.55 44.2±35.0 41.4±30.4 3.08±2.85 0.28 At 9 mo 40.0±36.1 49.9±35.5 −2.40±5.71 0.67 49.4±35.2 43.2±36.6 8.53±5.36 0.11 * Plus–minus values are means ±SD, unless otherwise indicated. Odds ratios are for complete recovery of facial nerve function. † For the primary outcome measure, odds ratios and P values have been adjusted for age, sex, the baseline score on the House–Brackmann scale, the receipt or nonreceipt of acyclovir and prednisolone, and the interval between the onset of symptoms and the initiation of a study drug. ‡ The House–Brackmann scale ranges from 1 to 6, with higher grades indicating worse facial paralysis. § Beta regression coefficients were calculated by adjusted multiple regression analysis. Plus–minus values in this category are means ±SE. ¶ For the secondary outcome measures, odds ratios and P values have been adjusted for baseline measurement of age, sex, score on the House–Brackmann scale, the receipt or non receipt of acyclovir and prednisolone, and the time from the onset of symptoms to the initiation of treatment. ‖ Scores on the Health Utilities Index Mark 3 range from –0.36 to 1.00 (as assessed by the patient), with 1 indicating full health; negative scores indicate a quality of life that is consid ered worse than death. ** Scores on the Brief Pain Inventory range from 0 to 110, with higher scores indicating greater severity. †† Scores on the Derriford Appearance Scale 59 range from 8 to 262, with higher scores indicating more distress and dysfunction.

Copyright © 2007 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved. Downloaded from www.nejm.org by DANIEL OLAUGHLIN MD on October 18, 2007 .

a difference of 19.4 percentage points (95% con-fidence interval [CI], 11.7 to 27.1; P<0.001). There was no significant difference between the com-plete-recovery rates in the acyclovir comparison groups: 71.2% for patients who received acyclovir and 75.7% for those who did not, a difference of 4.5 percentage points (95% CI, –12.4 to 3.3; un-adjusted P = 0.30; un-adjusted P = 0.50). At 9 months, the rates of complete recovery were 94.4% for pa-tients who received prednisolone and 81.6% for those who did not, a difference of 12.8 percentage points (95% CI, 7.2 to 18.4; P<0.001) and 85.4% for patients who received acyclovir and 90.8% for those who did not, a difference of 5.4 percentage points (95% CI, –11.0 to 0.3; unadjusted P = 0.07; adjusted P = 0.10). When the analyses were repeated with the results weighted according to the propen-sity of patients to withdraw from the study, there was no appreciable change.

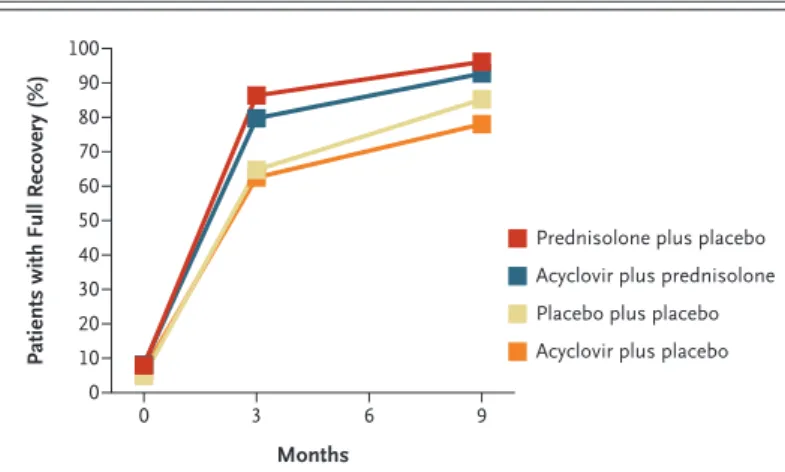

A total of 34 patients (6.9% of those who com-pleted follow-up) were assessed as fully recovered at the time of the first assessment visit (i.e., within at most 8 days after the onset of symptoms). For patients receiving double placebo, 64.7% were fully recovered after 3 months, and 85.2% after 9 months. Table 3 gives comparisons of all four treatment groups relative to each other. Predniso-lone was highly effective, both separately and in combination with acyclovir. Acyclovir was ineffec-tive, both separately and as an addition to pred-nisolone. Figure 2 shows the proportion of pa-tients assessed as having normal facial function at

baseline, at 3 months, and at 9 months in the four study groups.

Generally, there were no significant differences among the groups in secondary measures (Table 2). However, only patients who received predniso-lone had an improvement in the appearance score over time. Also, pain scores tended to be lower in the prednisolone group than in the group that did not receive prednisolone. On the other hand, the quality of life at 9 months was significantly higher for patients who did not receive prednisolone than for those who did (P = 0.04). Given that the sec-ondary measures were obtained only in patients who had not recovered at 3 months and given the problem of multiple testing, this result should be interpreted with caution.

At 3 months, the absolute risk reduction associ-ated with prednisolone treatment was 19%. There-fore, the number needed to treat in order to achieve one additional complete recovery was 6 (95% CI, 4 to 9). At 9 months, the equivalent numbers were an absolute risk reduction of 12% and a number needed to treat of 8 (95% CI, 6 to 14).

Adverse events included the expected range of minor symptoms associated with the drugs used (Table 4). During follow-up, three patients died. All three deaths were deemed to be unrelated to treat-ment: two patients had received double placebo and one had received acyclovir alone. No other major adverse events were reported. There was no need for patients or study personnel to be in-formed about study-group assignments.

Table 3. Complete Recovery at 3 Months and 9 Months, According to Treatment Combination, Adjusted for Baseline

Characteristics.*

Variable Prednisolone No Prednisolone

Odds Ratio (95% CI) P Value† Odds Ratio (95% CI) P Value†

At 3 mo

Patients who received acyclovir 1.73 (0.96–3.12) 0.07 0.85 (0.49–1.47) 0.57 Patients who did not receive acyclovir 2.58 (1.37–4.88) 0.003 1.00

At 9 mo

Patients who received acyclovir 1.76 (0.74–4.16) 0.20 0.58 (0.29–1.16) 0.12 Patients who did not receive acyclovir 3.23 (1.13–9.22) 0.03 1.00

* Odds ratios are for complete recovery, defined as grade 1 on the House–Brackmann scale, which ranges from 1 to 6, with higher scores indicating worse facial paralysis. Odds ratios and P values were adjusted for age, sex, baseline House–Brackmann grade, and the time from the onset of symptoms to the initiation of treatment. Odds ratios were calculated by comparing all three active treatments with double placebo. Significance testing for comparisons at 3 and 9 months had the following results: combination therapy versus prednisolone only, P = 0.18 (3 months) and P = 0.28 (9 months); combination therapy versus acyclovir only, P = 0.004 (3 months) and P = 0.001 (9 months); acyclovir only versus double placebo, P = 0.79 (3 months) and P = 0.19 (9 months); and prednisolone only versus double placebo, P<0.001 (3 months) and P = 0.004 (9 months).

n engl j med 357;16 www.nejm.org october 18, 2007 1605

Discussion

In this large, randomized, controlled trial of the efficacy of treatment for Bell’s palsy, we confirmed the generally favorable outcome for patients receiv-ing double placebo, with 64.7% of patients fully

recovered at 3 months and 85.2% at 9 months.9,10

Early treatment (within 72 hours after the onset of symptoms) with prednisolone increased these rates to 83.0% and 94.4%, respectively. Acyclovir produced no benefit over placebo, and there was no benefit in its addition to prednisolone.

The results of previous trials have been

incon-sistent.21 Our trial included twice as many patients

as were included in the Cochrane systematic

re-views.11,12 We recruited most patients from

pri-mary care practices, thus reducing the selection bias inherent in hospital-based studies. The high rate of acceptance of randomization and the low dropout rate during the study suggest that our re-sults can probably be applied to other settings with similar populations. It is possible that genetic polymorphisms that are prevalent in some popu-lations or environmental factors such as diet could alter the response. We used drugs that are rela-tively inexpensive and are readily available world-wide. The assessment of outcomes with the use of validated study tools was undertaken by observ-ers who were unaware of the assignments to study groups.

We used the House–Brackmann scale to grade facial-nerve function because it reliably assigns patients to a recovery status. The scale has been criticized for insufficient sensitivity to change and difficulty in assigning grades because patients may have contrasting degrees of function in different

parts of the face.22,23 This observation, as well as

rapid recovery between randomization and the home visit in some cases, may explain why 34 pa-tients received grade 1 on the House–Brackmann scale at their baseline assessment. Alternative scales, such as the Sydney and Sunnybrook facial grading systems, are available but are more

dif-ficult to use in clinical practice.24

We did not observe any benefits with respect to our secondary outcome measures (quality of life, appearance, and pain) in any study group, includ-ing patients who received prednisolone. There was some suggestion of a benefit from prednisolone in terms of reduced pain and improved appear-ance, but these differences were not significant. In the subgroup of patients who did not have a

complete recovery at 3 months and who underwent the 9-month assessment, there were reduced qual-ity-of-life scores among patients who were treated with prednisolone and also among those treated with acyclovir. Given the evidently reduced health status of those who required a health assessment at 9 months, this result is perhaps not surprising.

In conclusion, we have provided evidence that the early use of oral prednisolone in patients with Bell’s palsy is an effective treatment. The mecha-nism of action may involve modulation of the im-mune response to the causative agent or direct re-duction of edema around the facial nerve within the facial canal. Treatment with unesterified acy-clovir at doses used in other trials either alone or with corticosteroids had no effect on the outcome. Therefore, we cannot recommend acyclovir for use

in the treatment of Bell’s palsy.25,26 A recent study

in Japan suggested that valacyclovir (a prodrug that achieves a level of bioavailability that is three to five times that of acyclovir) may be a useful

ad-dition to prednisolone.27 However, the Japanese

study was smaller than ours, patients were treat-ed in tertiary centers, and the outcome assessors were aware of the study-group assignments; there-fore, the results of that study should be interpreted with caution.

No data are available regarding how best to treat patients who present more than 72 hours after the onset of symptoms, so all patients with suspected Bell’s palsy should be assessed as early as possible. Since most patients with this

condi-16p6 100

Patients with Full Recovery (%)

80 90 70 60 40 30 10 50 20 0 0 3 6 9

Prednisolone plus placebo Acyclovir plus prednisolone Acyclovir plus placebo Placebo plus placebo

Months AUTHOR: FIGURE: JOB: ISSUE: 4-C H/T RETAKE SIZE ICM CASE EMail Line H/T Combo Revised

AUTHOR, PLEASE NOTE:

Figure has been redrawn and type has been reset. Please check carefully.

REG F Enon 1st 2nd 3rd Sullivan 2 of 2 10-18-07 ARTIST: ts 35716

Figure 2. Patients Who Had a Full Recovery at 3 Months and 9 Months,

According to Study Group.

Full recovery was defined as grade 1 on the House–Brackmann facialnerve grading scale, which ranges from 1 to 6, with higher grades indicating worse facial paralysis.

Copyright © 2007 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved. Downloaded from www.nejm.org by DANIEL OLAUGHLIN MD on October 18, 2007 .

Appendix

In addition to the authors, the following investigators participated in the study. Trial Steering Committee: C. van Weel, University of Nij

megen; I. Williamson, University of Southampton; S. Wyke, University of Stirling; C. Hamilton (patient representative); Temporary Researcher:

D. Gray, University of Aberdeen.Local Principal Investigators: K. Ah-See, Aberdeen Royal Infirmary; N. Balaji, Monklands Hospital, Airdrie; H. Beg, Victoria Hospital, Kirkcaldy; Q. Gardiner, Perth Royal Infirmary; M. Hussain, Ninewells Hospital, Dundee; A. Kerr, Western General Hospital and

Royal Infirmary, Edinburgh; J. Marshall, Southern General Hospital, Glasgow; W. McKerrow, Raigmore Hospital, Inverness; M. Shanks, Crosshouse

Hospital, Kilmarnock; D. Simpson, Stobhill Hospital, Glasgow; G. Vernham, St. John’s Hospital, Livingston; A. White, Royal Alexandra Hospital,

Paisley.Scottish School of Primary Care: L. McCloughan, Scottish Primary Care Research Network; M. Pitkethly, East of Scotland Node; S.

Camp-bell, North of Scotland Node; A. Cardy, North of Scotland Node; C. Fulton, East of Scotland Node; J. McGill, West of Scotland Node; K. Bell, National

Health Service Ayrshire and Arran; B. Rae, North Glasgow Hospitals Trust.Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee: M. Campbell, C. Counsell,

University of Aberdeen; R. Mountain, S. Ogston (statistician), University of Dundee.

tion recover fully without any treatment, withhold-ing treatment will remain an appropriate strategy for some patients. Our study showed that the ad-ministration of prednisolone can increase the probability of complete recovery at 9 months, a finding that should help inform discussions about the use of corticosteroids for patients with Bell’s palsy.

Supported by a grant (02/09/04) from the Health Technology Assessment Programme of the National Institute for Health Research (Department of Health, England). The Scottish School

of Primary Care was funded by the Scottish Executive (Chief Scientist Office and National Health Service Education for Scot-land) during the study. Practices were reimbursed for their con-tributions through national Support for Science mechanisms.

Drs. Sullivan and Donnan report receiving grant support from GlaxoSmithKline for projects unrelated to this trial. No other potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Depart-ment of Health (England).

We thank all the patients, primary and secondary care doc-tors, dentists, and emergency staff members who contributed to this study.

Table 4. Adverse Events.

Event Prednisolone– Placebo PrednisoloneAcyclovir– Placebo– Placebo Acyclovir– Placebo Total number of events Dizziness 5 4 4 5 18 Dyspepsia 2 4 3 1 10 Nausea 1 2 3 3 9 Constipation 3 2 1 0 6 Hunger 1 1 0 2 4 Vomiting 0 2 1 0 3 Insomnia 1 1 1 0 3 Night sweats 2 1 0 0 3 Rash 0 1 0 2 3 Hot flushes 1 1 0 0 2 Depression 0 0 0 1 1 Thirst 0 0 1 0 1 Anorexia 0 1 0 0 1 Diarrhea 0 0 0 1 1 Drowsiness 0 0 1 0 1 Pruritus 0 1 0 0 1

Combinations of minor symptoms* 8 4 3 3 18

Death 0 0 2 1 3

Total 24 25 20 19 88

* Patients with two or more symptoms (e.g., dizziness and vomiting) are listed in this category only and are not duplicat ed in categories corresponding to a separate symptom (i.e., dizziness or vomiting).

n engl j med 357;16 www.nejm.org october 18, 2007 1607

References

Gilden DH. Bell’s palsy. N Engl J Med 2004;351:1323-31.

Adour KK, Bell DN, Hilsinger RL Jr. Herpes simplex virus in idiopathic facial paralysis (Bell palsy). JAMA 1975;233:527-30.

Stjernquist-Desatnik A, Skoog E, Au-relius E. Detection of herpes simplex and varicella-zoster viruses in patients with Bell’s palsy by the polymerase chain reac-tion technique. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 2006;115:306-11.

Theil D, Arbusow V, Derfuss T, et al. Prevalence of HSV-1 LAT in human tri-geminal, geniculate, and vestibular gan-glia and its implication for cranial nerve syndromes. Brain Pathol 2001;11:408-13.

De Diego-Sastre JI, Prim-Espada MP, Fernandez-Garcia F. The epidemiology of Bell’s palsy. Rev Neurol 2005;41:287-90. (In Spanish.)

Peitersen E. Bell’s palsy: the sponta-neous course of 2,500 peripheral facial nerve palsies of different etiologies. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl 2002;549:4-30.

Neely JG, Neufeld PS. Defining func-tional limitation, disability, and societal limitations in patients with facial paresis: initial pilot questionnaire. Am J Otol 1996; 17:340-2.

Williamson IG, Whelan TR. The clini-cal problem of Bell’s palsy: is treatment with steroids effective? Br J Gen Pract 1996;46:743-7.

Grogan PM, Gronseth GS. Practice parameter: steroids, acyclovir, and sur-gery for Bell’s palsy (an evidence-based review): report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology 2001;56:830-6.

Rowlands S, Hooper R, Hughes R, Burney P. The epidemiology and treat-1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10.

ment of Bell’s palsy in the UK. Eur J Neu-rol 2002;9:63-7.

Salinas RA, Alvarez G, Ferreira J. Cor-ticosteroids for Bell’s palsy (idiopathic facial paralysis). Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004;4:CD001942.

Allen D, Dunn L. Aciclovir or valaci-clovir for Bell’s palsy (idiopathic facial paralysis). Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004;3:CD001869.

Scottish Bell’s Palsy Study (SBPS). Dundee, Scotland: SBPS. (Accessed Septem-ber 21, 2007, at http://www.dundee.ac.uk/ bells/.)

McKinstry B, Hammersley V, Daly F, Sullivan F. Recruitment and retention in a multicentre randomised controlled trial in Bell’s palsy: a case study. BMC Med Res Methodol 2007;7:15.

University of Aberdeen Health Servic-es RServic-esearch Unit home page. (AccServic-essed September 21, 2007, at http://www.abdn. ac.uk/hsru/.)

House JW, Brackmann DE. Facial nerve grading system. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1985;93:146-7.

Furlong WJ, Feeny DH, Torrance GW, Barr RD. The Health Utilities Index (HUI) system for assessing health-related quali-ty of life in clinical studies. Ann Med 2001;33:375-84.

Harris DL, Carr AT. The Derriford Ap-pearance Scale (DAS59): a new psycho-metric scale for the evaluation of patients with disfigurements and aesthetic prob-lems of appearance. Br J Plast Surg 2001; 54:216-22.

Keller S, Bann CM, Dodd SL, Schein J, Mendoza TR, Cleeland CS. Validity of the Brief Pain Inventory for use in document-ing the outcomes of patients with non-cancer pain. Clin J Pain 2004;20:309-18. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. 17. 18. 19.

Preisser JS, Lohman KK, Rathouz PJ. Performance of weighted estimating equations for longitudinal binary data with drop-outs missing at random. Stat Med 2002;21:3035-54.

Cave JA. Recent developments in Bell’s palsy: does a more recent single research paper trump a systematic review? BMJ 2004;329:1103-4.

Coulson SE, Croxson GR, Adams RD, O’Dwyer NJ. Reliability of the “Sydney,” “Sunnybrook,” and “House Brackmann” facial grading systems to assess voluntary movement and synkinesis after facial nerve paralysis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2005;132:543-9.

Croxson G, May M, Mester SJ. Grad-ing facial nerve function: House-Brack-mann versus Burres-Fisch methods. Am J Otol 1990;11:240-6.

Ross BG, Fradet G, Nedzelski JM. De-velopment of a sensitive clinical facial grad-ing system. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1996;114:380-6.

Hato N, Matsumoto S, Kisaki H, et al. Efficacy of early treatment of Bell’s palsy with oral acyclovir and prednisolone. Otol Neurotol 2003;24:948-51.

Kawaguchi K, Inamura H, Abe Y, et al. Reactivation of herpes simplex virus type 1 and varicella-zoster virus and therapeutic effects of combination ther-apy with prednisolone and valacyclovir in patients with Bell’s palsy. Laryngoscope 2007;117:147-56.

Hato N, Yamada H, Kohno H, et al. Valacyclovir and prednisolone treatment for Bell’s palsy: a multicenter, random-ized, placebo-controlled study. Otol Neu-rotol 2007;28:408-13.

Copyright © 2007 Massachusetts Medical Society.

20. 21. 22. 23. 24. 25. 26. 27.

powerpointslidesofjournalfiguresandtables

At the Journal’s Web site, subscribers can automatically create PowerPoint slides. In a figure or table in the full-text version of any article at www.nejm.org, click on Get PowerPoint Slide. A PowerPoint slide containing the image, with its title and reference citation, can then be downloaded and saved.

Copyright © 2007 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved. Downloaded from www.nejm.org by DANIEL OLAUGHLIN MD on October 18, 2007 .

n engl j med 357;16 www.nejm.org october 18, 2007 1653 design, methods and preliminary accrual results of the

Canadi-an Cervical CCanadi-ancer Screening Trial (CCCaST). Int J CCanadi-ancer 2006; 119:615-23.

Naucler P, Ryd W, Törnberg S, et al. Human papillomavirus and Papanicolaou tests to screen for cervical cancer. N Engl J Med 2007;357:1589-97.

Noorani HZ, Brown A, Skidmore B, Stuart GCE. Liquid-10.

11.

based cytology and human papillomavirus testing in cervical cancer. Technology report no. 40. Ottawa: Canadian Coordinat-ing Office for Health Technology Assessment, 2003.

Kitchener HC, Almonte M, Wheeler P, et al. HPV testing in routine cervical screening: cross sectional data from the ARTISTIC trial. Br J Cancer 2006;95:56-61.

Copyright © 2007 Massachusetts Medical Society.

12.

Bell’s Palsy — Is Glucocorticoid Treatment Enough?

Donald H. Gilden, M.D., and Kenneth L. Tyler, M.D.Approximately a third of cases of acute peripheral facial weakness are caused by trauma, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, eclampsia, the Ramsay Hunt syndrome (facial palsy with zoster oticus caused by varicella–zoster virus), Lyme disease, sarcoidosis, Sjögren’s syndrome, parotid gland tu-mors, and amyloidosis and may even be a

compli-cation of intranasal influenza vaccine.1 The

re-maining two thirds of cases are idiopathic (Bell’s palsy).

Bell’s palsy occurs in 20 to 32 persons per

100,000 per year2,3 and affects both sexes and all

ages. Fortunately, most patients with Bell’s palsy recover completely, but 20 to 30% may have per-manent, disfiguring facial weakness or

paraly-sis.3,4 Besides the asymmetry evident from

limit-ed retraction of the muscles around the angle of the mouth on one side and an inability to close the eye (Fig. 1), there may be other permanent se-quelae, such as synkinesia, hyperacusis, a loss of taste, and an inability to produce tears. It is this substantial minority of patients with Bell’s palsy on whom early treatment is focused.

The rationale for early and aggressive treatment is based on long-standing observations by sur-geons who have reported the presence of facial-nerve swelling during decompression operations

in patients with Bell’s palsy.5 Edema may be

sec-ondary to ischemia6 or inflammation, as evidenced

by contrast enhancement of the facial nerve seen on magnetic resonance imaging 9 to 23 days after

the onset of Bell’s palsy.7 For years, physicians

have treated patients with Bell’s palsy as early as possible with glucocorticoids. In addition, the de-tection of herpes simplex virus in the endoneurial

fluid of patients with Bell’s palsy8 has led to the

widespread use of antiviral agents along with glu-cocorticoids in the past decade, although the ex-act role of the virus in disease pathogenesis is

un-known. Most, but not all, of the numerous studies that have compared glucocorticoid treatment with placebo in patients with Bell’s palsy have shown

significant improvement with glucocorticoids.9

Glucocorticoids also appear to confer a greater

benefit than acyclovir in these patients.10 Although

the collective data suggest that glucocorticoids de-crease the incidence of permanent facial paralysis, whether antiviral therapy confers additional ben-efits has not been known.

In this issue of the Journal, Sullivan et al.11

re-port on a large study involving the treatment of

09/20/07 Author Fig # Title COLOR FIGURE Version 2 Gilden 1 Bell’s palsy Inability to close eye Asymmetry of mouth

Figure 1. A Patient with Bell’s Palsy Who Has Been

Asked to Close His Eyes.

Typical signs include asymmetry from limited retrac-tion of the muscles around the angle of the mouth and an inability to close one eye.

Copyright © 2007 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved. Downloaded from www.nejm.org by DANIEL OLAUGHLIN MD on October 18, 2007 .

n engl j med 357;16 www.nejm.org october 18, 2007 1654

patients with Bell’s palsy. The study was random-ized, controlled, and double-blind, with pre-defined and specified outcome measures and fol-low-up for 9 months. Patients were recruited within 72 hours after the onset of symptoms from 17 hospitals in Scotland and were randomly assigned to treatment for 10 days with prednis-olone, acyclovir, or both or with placebo. The House–Brackmann scale was used to assess recov-ery of facial function. Assessment of final out-comes at 9 months, which was possible in 496 patients, revealed complete facial-nerve recovery in 85.2% of patients who received placebo,

support-ing earlier reports in untreated patients.12,13

Fur-thermore, 96.1% of patients who received prednis-olone alone recovered completely, an absolute risk reduction of 11%, as compared with those receiv-ing placebo alone. This absolute risk reduction means that 9 patients (95% confidence interval, 6 to 14) would need to be treated to achieve one additional full recovery.

Surprisingly, only 78.0% of patients who re-ceived acyclovir alone had recovered fully at 9 months, a proportion somewhat less than that after placebo treatment, and the percentage of patients who were completely recovered after treat-ment with a combination of acyclovir and pred-nisolone was slightly less (92.7%) than after treat-ment with prednisolone alone (96.1%). Overall, there was no evidence of benefit from acyclovir over placebo or from the combination of acyclo-vir and prednisolone over prednisolone alone.

The lack of benefit from antiviral therapy that is reported by Sullivan et al. conflicts with the re-sults of a recent prospective, randomized,

placebo-controlled study by Hato et al.14 that compared

a combination of valacyclovir (at a dose of 500 mg twice daily for 5 days) and prednisolone with

pla-cebo and prednisolone.14 A complete recovery was

seen in 96.5% of 114 patients who received val-acyclovir and prednisolone, as compared with 89.7% of 107 patients who received placebo and prednisolone (an absolute risk reduction of 6.8%). More striking was the report of the full recovery of 90.1% of patients with complete facial palsy who were treated with valacyclovir and prednis-olone, as compared with 75.0% of those treated with placebo and prednisolone. This finding extrapolates to a need to treat approximately 15 patients among the total group with Bell’s palsy or approximately 7 patients in the subgroup with complete facial palsy to achieve one

addi-tional full recovery. The patients in the study by Hato et al. appear to have had more severe facial palsy than those in the study by Sullivan et al. (The average Yanagihara score in the study by Hato et al. was approximately 15, which falls between House–Brackmann grades 4 and 5, as compared with a mean score of 3.6 in the study by Sullivan et al.). In the study by Hato et al., the benefit of valacyclovir and prednisolone over pla-cebo and prednisolone appeared to correlate with the severity of the facial palsy (an absolute risk reduction of 15.1% in patients with complete palsy and 5.7% in those with severe palsy, as com-pared with no reduction in those with moder-ate palsy). However, there were several methodo-logic limitations in the study by Hato et al. First, the investigators who were administering the treatment and assessing the outcome were aware of study-group assignments. Second, only 75% of patients who were enrolled in the study and underwent randomization were ultimately ana-lyzed, as compared with 91 to 95% in their simi-lar groups in the study by Sullivan et al.

How are the results from these two studies to be integrated into clinical practice? Although most patients with Bell’s palsy improve spontaneously, the use of prednisolone within 72 hours after the onset of symptoms decreases permanent facial disfigurement. In the United States, oral predni-sone (at a dose of 1 mg per kilogram of body weight for 7 to 10 days) is used more often than prednisolone, and the cost of prednisone is less than $11 for a course of 7 to 10 days. Further-more, the number needed to treat (approximately nine) to see one additional complete recovery from facial palsy is small.

The study by Sullivan et al. clearly indicates that the addition of acyclovir provides no addition-al benefit to treatment with glucocorticoids addition-alone. But what about valacyclovir? Valacyclovir is a pro-drug that is nearly completely converted to

acyclo-vir and L-valine and has substantially increased

bioavailability, as compared with acyclovir. Both Hato et al. and Sullivan et al. show no benefit of antiviral therapy in patients with moderate palsy and thus provide no rationale for treating these patients with valacyclovir. The cost of a 5-day course of 500 mg of valacyclovir twice daily is ap-proximately $70, and the number needed to treat for one additional full recovery in patients with complete facial palsy is approximately seven. Al-though the study by Hato et al. was

methodologi-Copyright © 2007 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved. Downloaded from www.nejm.org by DANIEL OLAUGHLIN MD on October 18, 2007 .

cally flawed, the use of valacyclovir in combina-tion with glucocorticoids could still be considered in patients with severe or complete facial palsy.

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

From the Departments of Neurology (D.H.G., K.L.T.), Microbi-ology (D.H.G., K.L.T.), and Medicine (K.L.T.), University of Col-orado School of Medicine; and the Neurology Service, Denver Veterans Affairs Medical Center (K.L.T.) — both in Denver.

Mutsch M, Zhou W, Rhodes P, et al. Use of the inactivated intranasal influenza vaccine and the risk of Bell’s palsy in Swit-zerland. N Engl J Med 2004;350:896-903.

Katusic SK, Beard CM, Wiederholt WC, Bergstralh EJ, Kurland LT. Incidence, clinical features, and prognosis in Bell’s palsy, Rochester, Minnesota 1968-1982. Ann Neurol 1986;20:622-7.

Peitersen E. Bell’s palsy: the spontaneous course of 2,500 peripheral facial nerve palsies of different etiologies. Acta Oto-laryngol Suppl 2002;549:4-30.

Idem. The natural history of Bell’s palsy. Am J Otol 1982;4: 107-11.

Cawthorne T. The pathology and surgical treatment of Bell’s palsy. Proc R Soc Med 1951;44:565-72.

Fowler EP Jr. Medical and surgical treatment of Bell’s palsy. Laryngoscope 1958;68:1655-62. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6.

Yetiser S, Kazkayas M, Altinok D, Karadeniz Y. Magnetic resonance imaging of the intratemporal facial nerve in idiopath-ic peripheral facial palsy. Clin Imaging 2003;27:77-81.

Murakami S, Mizobuchi M, Nakashiro Y, Doi T, Hato N, Yanagihara N. Bell palsy and herpes simplex virus: identifica-tion of viral DNA in endoneurial fluid and muscle. Ann Intern Med 1996;124:27-30.

Gilden DH. Bell’s palsy. N Engl J Med 2004;351:1323-31. De Diego JI, Prim MP, De Sarriá MJ, Madero R, Gavilán J. Idiopathic facial paralysis: a randomized, prospective, and con-trolled study using single-dose prednisone versus acyclovir three times daily. Laryngoscope 1998;108:573-5.

Sullivan FM, Swan IRC, Donnan PT, et al. Early treatment with prednisolone or acyclovir in Bell’s palsy. N Engl J Med 2007;357: 1598-607.

Grogan PM, Gronseth GS. Steroids, acyclovir, and surgery for Bell’s palsy (an evidence-based review): report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurolo-gy. Neurology 2001;56:830-6.

Rowlands S, Hooper R, Hughes R, Burney P. The epidemiol-ogy and treatment of Bell’s palsy in the UK. Eur J Neurol 2002; 9:63-7.

Hato N, Yamada H, Kohno H, et al. Valacyclovir and prednis-olone treatment for Bell’s palsy: a multicenter, randomized, pla-cebo-controlled study. Otol Neurotol 2007;28:408-13.

Copyright © 2007 Massachusetts Medical Society.

7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14.

STAT3 Signaling and the Hyper-IgE Syndrome

David E. Levy, Ph.D., and Cynthia A. Loomis, M.D., Ph.D. The Janus kinase (JAK)–signal transducer andactivator of transcription (STAT) signaling path-way has emerged over the past decade as a major relay between cell-surface receptors and cytokine responses. The human genome encodes four JAK family members — JAK1, JAK2, JAK3, and

tyro-sine kinase 2 (TYK2) — and seven STAT proteins.1

JAKs are protein tyrosine kinases that interact with the intracellular domains of cytokine re-ceptors (Fig. 1) and that have enhanced catalytic activity toward substrate proteins after receptor activation. The primary JAK substrates are STAT proteins — latent transcription factors that re-quire their tyrosine residues, and sometimes ser-ine residues, to be phosphorylated before they can induce the transcription of target genes.

The primary model of JAK-STAT signaling was established by delineation of the interferon pathway — wherein the JAK-STAT

signal-trans-duction system was discovered.2 Oligomerization

of cytokine receptors in response to ligand bind-ing leads to transphosphorylation of associated JAK enzymes, stimulating their ability to phos-phorylate both the cytoplasmic domains of the

cytokine receptors and the subsequently recruit-ed STAT proteins (Fig. 1). Once phosphorylatrecruit-ed, the STAT proteins dimerize through interactions between the phosphotyrosine and SRC homolo-gy 2 (SH2) domains. Active dimers accumulate in the cell nucleus, bind specific DNA target se-quences of gene promoters, and recruit coactiva-tor and transcriptional regulacoactiva-tory proteins that drive gene expression. The requirement of signal-dependent phosphorylation of STAT tyrosine resi-dues, coupled with the sensitivity of STAT to de-phosphorylation by nuclear phosphatases, renders the protein a dynamic, sensitive on–off switch for gene expression.

Molecular genetic analysis of cells from hu-mans and from engineered mice has revealed that STAT proteins usually have highly specific func-tions, dictated both by the specific receptors that serve as activators and by the intrinsic DNA bind-ing preferences of STATs and thus their spectrum of target genes. This inherent specificity is most easily observed in the phenotypes of mice

lack-ing individual Stat genes (Table 1). Mice lacking