Clinical Profile of Alcoholic Liver Disease in

a Tertiary Care Centre and its Correlation

with Type, Amount and Duration of Alcohol

Consumption

Nitya Nand

1, Parveen Malhotra

2, Dipesh Kumar Dhoot

3Various studies have shown different results about the role of drinking pattern including amount, duration and type of alcohol in the pathogenesis of disease. A few of them showed a dose-dependent effect on the risk of developing ALD, while others showing a threshold effect, above which the risk of development of cirrhosis was not further influenced by the amount of alcohol.1-3 South Asian race and female sex are more prone to develop liver disease with lesser alcohol consumption and in shorter duration of time than their counterparts.3-7 Illicitly brewed liquor has been found to be more toxic than licit drinks despite low level of alcohol in a study.8 The extent of protein calorie malnutrition may also play an 1Senior Professor and Unit Head, 2Associate Professor, 3Resident, Department of Medicine, Pt. B. D. Sharma Post-Graduate Institute of Medical Sciences, Rohtak, Haryana

Received: 25.04.2013; Revised: 13.09.2013; Re-revised: 12.02.2014; Accepted: 28.03.2014

O r i g i n a l a r t i c l e

Abstract

Introduction: Alcoholic liver disease (ALD) is a major cause of mortality and morbidity worldwide. Various studies show contradictory results about the role of amount, type and duration of alcohol exposure in determining the risk to develop ALD with ethnic variations in susceptibility to develop ALD and South Asians are shown to be more prone to develop ALD. This study was carried out to evaluate clinical profile of ALD in Indian population and to find out the correlation of disease severity and outcome with alcohol intake.

Material and Methods: 201 patients of ALD were evaluated to correlate their clinical complications, biochemical parameters, prognostic markers (Discriminant function [DF] score, Model for end-stage liver disease [MELD] score and Child-Pugh score) and in-hospital mortality with their alcohol intake data in form of type, amount and duration of alcohol intake.

Results: Hepatic encephalopathy, neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio (NLR)

and all three prognostic scores showed a dose-dependent relation

with the amount of alcohol intake (p <0.05). However, the mortality rate didn’t show a significant relation with amount. Further the type of alcohol intake didn’t show any relation with disease severity; however, the duration of alcohol intake showed a positive relation with mortality rate. NLR emerged as a useful bedside marker of disease severity which correlates well with all prognostic markers (p <0.05 for NLR’s Spearman correlation with DF score and Child-Pugh Score), more so with MELD score (p <0.0001); and complications like hepatic encephalopathy and hepato-renal syndrome. NLR also correlated with mortality rate but it was not statistically significant.

Editorial Viewpoint

• ALD is a major health p r o b l e m a c r o s s t h e country at all the levels of healthcare systems • T h i s s t u d y s h o w s

c o r r e l a t i o n b e t w e e n a l c o h o l i n t a k e a n d prognostic scores.

• Type of alcohol did not show correlation with the severity of ALD.

Introduction

A

lcoholic liver disease (ALD) and its complications are major causes of mortality and morbidity worldwide. However, every person consuming alcohol does not develop the disease and a number of factors determine the overall risk of developing thedisease in a given patient. These may include amount, duration and type of the alcohol consumed, nutritional status, co-morbid conditions, race, sex and genetic factors etc.

important role in determining the outcome of patients with ALD.9,10

Since there are considerable variations among different studies and most of these studies have been done more than a decade ago in Western population. Western data from research done on Caucasian population can’t be applied blindly to Indian population in view of the ethnic differences, and very few studies have been carried out in Indians. Hence we planned this study to get a detailed profile of alcoholic liver disease patients in Indian population, including their alcohol consumption data, disease severity and outcome.

Material and Methods

Two hundred one adult patients of chronic liver disease with a significant history of alcohol c o n s u m p t i o n d e t e r m i n e d b y AUDIT-C score ≥4 were selected for study. HIV, hepatitis B or C positive and hemodynamically unstable patients were excluded from the study. A pre-informed written consent was obtained from each participant (or attendant if patient was unconscious).

A detailed alcoholism history and clinical history was taken from each patient and complete physical examination was done. Various biochemical and ultrasonographic findings were recorded on a specially designed performa. Alcoholism history included four measures – type, duration (years), amount (units per day) and frequency (days per month). We arbitrarily divided the amount of alcohol intake as light when alcohol intake was <360 units per month, moderate 360-719 units per month and heavy 720 unit or more per month.

A unit of alcohol was defined as amounts of liquor equivalent to 10 gram of pure alcohol. This amount equates roughly to 30 ml of spirits (concentration 40% by volume, e.g. whisky, vodka, gin), 100 ml of wine or 250 ml of beer.11

Alcohol concentration in local country-made spirits have no fixed standards, ranging from 25% to 50% by volume. Hence in present study, a unit of country liquor was also taken as 30 ml, equivalent to branded spirits.

The duration was defined as short when it was up to 10 years, moderate when it was 11-20 years and long if it was more than 20 years. Average amount per month was calculated by multiplying daily amount with frequency. Patients were divided according to their type (country, whiskey and variable drinkers), amount and duration. Based upon these clinical and biochemical data, various prognostic markers (Maddrey’s Discriminant function score [DF] score, Model for end-stage liver disease [MELD] score and Child-Pugh score) were calculated for each participant. All the admitted p a r t i c i p a n t s w e r e o b s e r v e d during hospitalization for any complications of alcoholic liver disease. Disease outcome in terms of either death or improvement was noted and in-hospital mortality rate was calculated.

All these data were compared and correlated to each other to determine –

1. Comparison of complication rate, prognostic scores and mortality rate among different groups according to type, a m o u n t a n d d u r a t i o n o f alcoholism.

2. C o r r e l a t i o n o f d i f f e r e n t biochemical and hematologic parameters with complication rate, prognostic scores and mortality rate.

3. Comparison of mortality rates between low risk and high risk groups of different prognostic scores.

Statistical Analysis: All the statistical comparisons were done with GraphPad Instat Version 3.0 software and p values were obtained. Categorical data were compared with Fisher’s Exact test

for 2 groups and Chi-square test for ≥3 groups and Odds ratio with 95% confidence interval was calculated. Quantitative data were compared with analysis of variance (ANOVA) test. Various prognostic markers were correlated to each other and with NLR by Spearman’s non-parametric correlation test.

Results

The study comprised of 201 male alcoholic patients with mean age of 46.2±9.86 years and mean weight of 58±6 kg. Majority of them have been consuming country-made spirits (79%), other consuming branded spirits like whisky (6.5%) and variable drinkers (14%) while only 1 patient (0.5%) was consuming beer. Country-drinkers consumed more amount (499 units per month) as compared to whisky (328 units/ month) and variable consumers (381 units/month). Average duration of alcohol intake was 17 years which was not significantly different among various liquor groups. Abdominal pain (55%), distension (78%) and jaundice (60%) were the most common symptoms while ascites (72%), pedal edema (60%) and icterus (62%) were the most common clinical signs, followed closely by splenomegaly (57%). Hepatic failure, parotid swelling (20%) and alopecia (17%) were most common amongst the peripheral signs followed by clubbing (9%) and spider nevi (9%). Ultrasound revealed hepatomegaly (42%) to be more common than small shrunken liver (13%) in alcoholic liver patients. Splenomegaly (57%) was common and it was mild (42%) in most of the patients. Ascites (72%) was most common among the markers of portal hypertension; followed by splenomegaly and dilated portal vein (53%) where as the portal venous collaterals (3.5%) were least common.

Basic biochemical investigations showed anemia in 87% of patients and leukocytosis in 36% patients, d i f f e r e n t i a l c o u n t s s h o w e d polymorphonuclear predominance

(as evidenced by mean N/L Ratio of 5.5±3.4). Liver function tests revealed elevated transaminases with mean AST/ALT ratio of 2.15±0.88. Hyperbilirubinemia was seen in 85% patients (mean bilirubin 5.28±6.03 mg/dL). However serum bilirubin >3 mg/dL was found in around 52% of patients. Mean albumin levels were 2.79±0.62 g/dL and severe hypoalbuminemia ( < 3 g / d L) wa s s e e n i n 6 5 % , and coagulopathy (mean INR 2.08±0.89) were also common biochemical findings. However

none of biochemical abnormalities correlated with type, amount or duration of alcohol intake. Risk of upper gastrointestinal bleed didn’t correlate with coagulopathy (INR levels) or with portal hypertension (PVD ≥13 mm); probably because of relative collapse of varices after bleed, thus showing relatively normalized portal vein diameter (PVD).

Common complications were ascites (72%), hepatorenal syndrome (35%), hepatic encephalopathy ( 5 9 % ) a n d g a s t r o i n t e s t i n a l

bleeding (59%). Patients with encephalopathy and HRS had a higher in-hospital mortality rate which showed a significant linear correlation with derangement of mental status (in encephalopathy) and serum creatinine (in HRS). However mortality rates were not seen to be higher in ascites and gastrointestinal bleed patients, which can be due to our biased selection of patients (massively bleeding patients were excluded due to hemodynamic instability). None of these complications except for hepatic encephalopathy correlated with type (Table 1), amount (Table 2), or duration (Table 3) of alcohol consumption. Hepatic encephalopathy correlated well with amount (more common in heavy drinkers) but not with type or duration (Table 1, 2, 3).

NLR correlated well with all three prognostic scores by Spearman’s non-parametric correlation and the correlation coefficient ‘ρ’ was found to be 0.164 (p <0.05) with Maddrey DF score; 0.279 (p <0.001) with MELD score and 0.169 (p <0.05) with Child-Pugh score. Thus the correlation was significant with all three prognostic markers but it was extremely significant with MELD score (Figure 1). NLR also correlated well with amount of alcohol consumption (ρ 0.172, p <0.05) but not with duration of alcohol intake. When patients were divided into low (<2.5), medium (2.5 - 4.5) and high (>4.5) risk group based upon NLR and these groups were compared for complication rate, mean prognostic scores and mortality rate. All the three prognostic markers as well as hepatorenal syndrome were found to be significantly higher in high NLR group as compared to low and medium NLR groups (Figure 2). Hepatic encephalopathy and mortality rate were also higher in high N/L ratio group, although difference couldn’t reach the limit of statistical significance (Table 4). Hepatic transaminases and serum albumin were not found Table 1: Comparison of patients drinking different alcoholic beverages –

complication rates, prognostic markers and outcome

Country Whisky Variable P-value

(N=159) (N=13) (N=28) Complications Encephalopathy 93 (58.5%) 7 (53.8%) 18 (64.3%) 0.785 Ascites 116 (72.9%) 8 (61.5%) 20 (71.4%) 0.676 HRS 56 (35.2%) 5 (38.5%) 9 (32.1%) 0.917 GI bleed 95 (59.7%) 6 (46.2%) 17 (60.7%) 0.62 N/L ratio 5.74 4.62 4.60 0.168 Prognosis and

outcome DF scoreMELD score 55.4020.83 50.2218.61 52.0819.77 0.860.66

Child-Pugh 10.9 10.38 11.14 0.64

Mortality 20% 18.2% 21% 0.982

Table 2: Effect of amount of alcohol exposure – complication rates, prognostic markers and outcome

Unit / Month <360 360 – 719 >720 P-value

(N=55) (N=75) (N=71) Complications Encephalopathy 28 (50.91%) 39 (52%) 51 (71.83%) 0.020 Ascites 37 (67.27%) 56 (74.67%) 52 (73.24%) 0.628 HRS 17 (30.9%) 26 (34.67%) 27 (38%) 0.707 GI bleed 36 (65.45%) 39 (52%) 44 (62%) 0.256 N/L ratio 4.64 5.44 6.21 0.035 Prognosis and

outcome DF scoreMELD score 44.1217.97 53.4920.06 63.5522.89 0.0350.014 Child-Pugh 10.29 10.79 11.48 0.017

Mortality 17.5% 18.9% 22.4% 0.814

Table 3: Effect of duration of alcohol exposure – complication rates, prognostic markers and outcome

Duration Upto 10 yr 11-20 yr >20 yr P-value

(N=51) (N=98) (N=52) Complications Encephalopathy 24 (47.1%) 60 (61.2%) 34 (65.4%) 0.13 Ascites 39 (76.5%) 73 (74.5%) 33 (63.5%) 0.26 HRS 17 (33.3%) 36 (36.7%) 17 (32.7%) 0.856 GI bleed 33 (64.7%) 57 (58.2%) 29 (55.8%) 0.63 N/L ratio 5.59 5.15 6.02 0.32 Prognosis and

outcome DF scoreMELD score 19.2954.5 58.3521.78 47.1419.23 0.300.18 Child-Pugh 10.33 11.37 10.56 0.02 Mortality 5.26% 27.8% 19.5% 0.019 HRS: Hepatorenal syndrome; GI: Gastrointestinal; N/L ratio: Neutrophil:Lymphocyte ratio; DF score: Discriminant function score; MELD: Model for end-stage liver disease

Fig. 1: Correlation of NLR with MELD score

Fig. 2: Correlation of NLR with complications prognosis and outcome to be significantly associated

with incidence of complications. Bilirubin and INR were found to be significantly associated with incidence of complications. Encephalopathy and death rate was higher in hyperbilirubinemic patients although the difference was not much significant (p = 0.0578 and 0.0687, respectively). The incidence of ascites and encephalopathy were higher in patients with higher INR values (p-value 0.0089 and 0.0342, respectively).

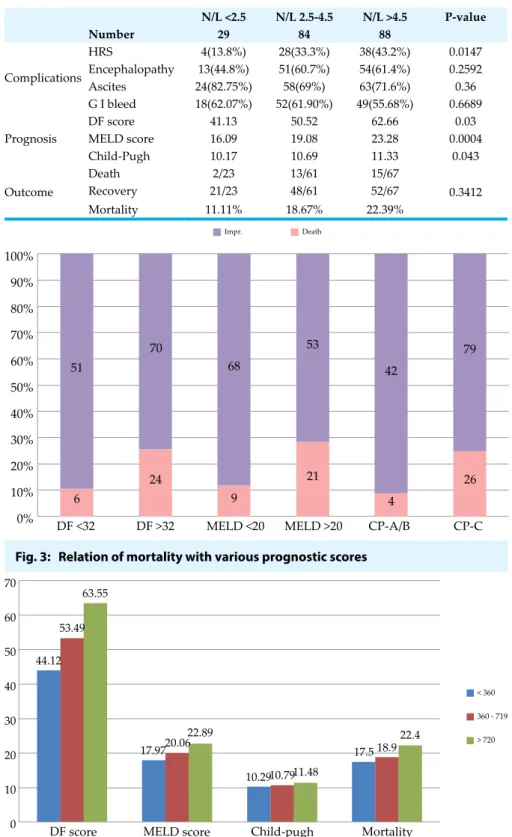

The three prognostic scores i.e. Maddrey DF, MELD and Child-Pugh scores were calculated and

mortality rates were found to be significantly higher in the high risk groups of all three markers (Figure 3). Child-Pugh score was the most sensitive in detecting high risk (0% mortality in low risk group A) while DF and MELD scores were found to be more specific. Mortality rates also differed among different age groups, with significantly higher rates in older age groups.

W h e n c o r r e l a t e d w i t h alcohol consumption data; the complications, prognostic markers or mortality rate didn’t vary amongst various types of alcohol intake (Table 1). However all the

three prognostic markers correlated well with amount of alcohol intake (Table 2) but mortality rate didn’t show any correlation with it (Figure 4). On the contrary, none of the complications and prognostic markers (except child-Pugh score) varied significantly amongst patients drinking for different durations but mortality rate was significantly higher in those drinking for >10 yrs (Table 3). This difference however could probably be due to presence of age as a confounding factor in these groups as the groups were not comparable in their mean age.

Discussion

The association of alcohol with cirrhosis was first recognized by Matthew Baillie in 1793. Despite considerable research since the 1950s, many important facets of this disease have yet to be resolved. One of these important questions is: Why does cirrhosis develop in only a small fraction of heavy alcohol abusers? What are the factors that predispose someone to the development of liver disease? The explanation of the apparent predisposition of certain people to develop alcoholic cirrhosis is unknown, although recent studies showing role of genetic polymorphisms have attempted to explain these differences between alcoholic cirrhotics and healthy alcoholics, complete molecular pathogenic mechanisms are yet to be proven.

Quantity and duration of alcohol intake are considered the most important risk factors involved in the development of alcoholic liver disease. The ideal, but unfeasible, study design for estimation of the risk function is a prospective monitoring of alcohol consumption and recording of the rate of development of cirrhosis per unit of time. Hozo et al in their study of alcoholic liver disease patients in Croatia proved by mathematical model that the occurrence of liver cirrhosis increases exponentially

MELD score 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 0 50 100 NLR 150 200 250 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 13.8 33.3 43.2 41.13 50.52 62.66 16.0919.08 23.28 10.17 10.69 11.33 11.11 18.6722.39 N/L <2.5 N/L 2.5-4.5 N/L >4.5 HRS DF score MELD score

Child-Pugh score Mortality

Table 4: Correlation of N/L Ratio with various complications, prognostic markers and outcome N/L <2.5 N/L 2.5-4.5 N/L >4.5 P-value Number 29 84 88 Complications HRS 4(13.8%) 28(33.3%) 38(43.2%) 0.0147 Encephalopathy 13(44.8%) 51(60.7%) 54(61.4%) 0.2592 Ascites 24(82.75%) 58(69%) 63(71.6%) 0.36 G I bleed 18(62.07%) 52(61.90%) 49(55.68%) 0.6689 Prognosis DF score 41.13 50.52 62.66 0.03 MELD score 16.09 19.08 23.28 0.0004 Child-Pugh 10.17 10.69 11.33 0.043 Outcome Death 2/23 13/61 15/67 0.3412 Recovery 21/23 48/61 52/67 Mortality 11.11% 18.67% 22.39%

that above a rather low level of alcohol consumption, the risk of development of cirrhosis was not further influenced by the amount of alcohol consumed.2 Thus it is clear that many different studies have given different cut-off levels of “safe drinking” though it has been recognized that no level of alcohol amount is absolutely safe.

Narawane et al studied 328 patients from a public hospital in Mumbai and found that liver disease was more common in those who consumed illicitly-brewed as compared to licit liquor.8 Daily drinking, volume of alcohol consumption >200 ml per day, and duration of drinking >14 years were significantly more common in those with liver disease. A cumulative intake of >2000 ml. years, calculated as the product of volume (ml per day) and duration (years), was a reliable cut-off level for association with liver disease. The content of alcohol in these liquors, estimated in 23 samples, ranged from 23-36.1 g/100 ml, being lower in the illicit liquors. Thus, in Mumbai, they suggested the alcoholic liver disease occurred more commonly with consumption of illicit liquor (despite its lower alcohol content) and liver involvement appeared earlier and with lower consumption levels than in the West.8

In our study, most of the patients were consuming local country-made liquor (79%) but no significant difference was found between the disease severity in country liquor consumers and branded whisky consumers. Incidence of complications, various prognostic markers and mortality rate were similar in country liquor and branded liquor consumers.

I n n o n - b r a n d e d a l c o h o l , concentration of alcohol is usually lower than branded alcohol but the effect is more or less similar. No significant difference was noted in the complications, prognostic scores and mortality rates between branded and non-branded alcohol in our study. The exact difference Fig. 3: Relation of mortality with various prognostic scores

Fig. 4: Correlation of alcohol amount with prognosis and outcome with the increase of the amount

of alcohol consumed.1 Becker et al in their large population-based prospective cohort study in Copenhagen also observed similar dose-dependent rise in the risk.3 The

level of alcohol intake above which the relative-risk was significantly greater than 1 was observed at 7 to 13 beverages per week for women and 14 to 27 beverages per week for men. Savolainen et al suggested

Impr. Death 100% 90% 80% 70% 60% 50% 40% 30% 20% 10% 0% 51 70 68 53 79 26 4 21 9 24 6

DF <32 DF >32 MELD <20 MELD >20 CP-A/B CP-C 42 70 60 50 40 30 20 10

0 DF score MELD score Child-pugh Mortality 44.12 53.49 63.55 17.9720.06 22.89 10.2910.7911.48 17.5 18.9 22.4 < 360 360 - 719 > 720

in the concentration or amount of alcohol between branded and non-branded alcohol could not be determined because we didn’t test the samples for the concentration of alcohol or other toxins/impurities. However, previous studies have shown the role of impurities in the higher incidence of ALD in country liquor drinkers.

S i m i l a r l y t h e d u r a t i o n o f alcoholism also didn’t affect the incidence of complications and prognostic markers (except Child-Pugh score) but Child-Child-Pugh score and overall mortality rate was significantly lower in patients with alcohol exposure of less than 10 years as compared to those with alcohol history of more than 10 years. Although this difference in mortality rate was found to be statistically significant, age remained a confounding factor in this analysis as the groups were not comparable in their mean age. Patek et al had found in their study that only 34% of cirrhotic patients had been drinking for <20 years12 while in the Indian study done by Narawane et al 86% of the cirrhotic patients were drinking for <20 years.8 In our study 149 patients (74%) had been drinking for ≤20 yrs which is close to the previous Indian study and it further consolidates the fact that Indians develop liver disease in lesser duration than Western population.

The higher incidence of cirrhosis in South Asians than Caucasians, despite lesser amount of alcohol and in lesser duration of alcohol intake, has been thought to be due to genetic polymorphisms of genes responsible for alcohol metabolism like ADH, ALDH and CYP2E1 and genes responsible for inflammatory cytokine production like TNF-α and IL-10. Most of these studies have been done in western population and oriental population and these studies show significant difference in prevalence of these gene alleles between Caucasians and Asians. A recent

study including 175 alcoholic cirrhotic patients, 140 non-alcoholic cirrhotic patients, 255 non-alcoholic controls and 140 alcoholic controls; done in Lucknow revealed that the ADH1C*1/*1 genotype exhibited s i g n i f i c a n t a s s o c i a t i o n w i t h alcoholic liver cirrhosis while ADH1B genotypes did not show any significant association.14 A much higher risk to alcoholic liver cirrhosis was observed in patients carrying a combination of wild genotypes of ADH1C (ADH1C*1/*1) and variant genotype of ADH1B (ADH1B*2/*2) or CYP2E1 (CYP2E1*5B) or null genotype of glutathione s-transferases M1 (GSTM1). Another study done at AIIMS including 174 alcoholics showed that hepatic transaminases were significantly increased, age of onset of alcohol dependence was significantly lesser and duration of dependence was significantly higher in those with ALDH2*1/*1 a s c o m p a r e d t o A L D H 2 * 2 / * 2 genotype, suggesting protective role of the latter genotype from alcoholism as well as alcoholic liver disease.15 Although it is worth mentioning that average alcohol consumption of these groups was also not comparable (4-8 times more alcohol consumption in ALDH2*1/*1 group as compared to ALDH2*2/*2 group). Thus it can be concluded that effect of genetic polymorphism on alcoholic liver disease may probably be indirect due to higher alcohol consumption due to higher tolerance. The genotypic frequencies of these two alleles were found to be 73% and 11% respectively. The ADH1B*2 allele, which is known to confer protection against alcoholism and is relatively common in East Asian populations, was found to be present at very low frequency (0.001) in their study. Another study done by Bhaskar et al in 397 healthy individuals from six tribal populations from various parts of India reported that ALDH2*2/*2 allele was absent in Indians.16 Thus both of the protective genotypes

have been shown to be rare in Indian population which provides a possible explanation for their predisposition to develop alcoholic liver disease with lesser amount and lesser duration of alcohol intake.

When correlating with amount of alcohol consumption, hepatic encephalopathy was significantly more common in heavy drinkers than light and moderate drinkers. Comparatively non-significant difference between light and moderate group and significant difference between moderate and heavy groups suggests the threshold to be near 720 units/month or approximately 24 units per day. A positive correlation was also seen between alcohol amount and all three prognostic scores, which were found to be significantly higher in the heavy drinkers but other three complications (HRS, GI bleed and ascites) and overall mortality rate were not significantly higher in heavy drinkers (Figure 4). Previous study of Narawane et al didn’t comment about the complications or mortality rate but they found s i g n i f i c a n t l y h i g h e r a l c o h o l consumption in the patients with liver disease than the alcoholics without liver disease. Among those with liver disease, cirrhotics were found to drink more alcohol than non-cirrhotics. Thus this study and the previous study by Narawane et al, both show a significant correlation between alcohol amount and disease progression.

P h y s i c a l e x a m i n a t i o n a n d imaging findings in this study s h o w e d s i m i l a r r e s u l t s a s seen in the pioneer study of Mendenhall CL (jaundice 60%, ascites 57%, splenomegaly 26%, and hepatomegaly 87%).13 Two remarkable differences are higher incidence of splenomegaly and a lower incidence of hepatomegaly in this study as compared to that of Mendenhall. This difference was probably because the study group of Mendenhall predominantly contained alcoholic hepatitis

patients while this study consists of whole spectrum of alcoholic liver disease including cirrhotics. Similarly, Mendenhall showed higher level of bilirubin in moderate alcoholic hepatitis than mild and severe hepatitis and their average levels were higher (1.6, 13.5 and 8.7 mg/dL in mild, moderate and severe disease respectively) than this study. This difference could also probably be due to the same reason.

Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio (NLR) has been recently used as a non-invasive marker to assess the severity and to determine the probability of NASH in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. It has also been used as a predictor o f b a c t e r e m i a i n m e d i c a l emergencies and to predict the recurrence of HBV-associated hepatocellular carcinoma after liver transplantation. Apart from this, prognostic value of NLR in patients presenting with ST-elevation myocardial infarction undergoing primary percutaneous coronary interventions has also been proven in some studies. Till date, there is no study about its role in alcoholic liver disease as a prognostic marker. It is a simple, easy and commonly available bedside diagnostic tool which can be easily used in the most peripheral areas to assess the disease severity. Hence in this study we evaluated the utility of NLR as a prognostic marker in ALD and we correlated NLR with three well-established prognostic markers i.e. Maddrey DF, MELD score and Child-Pugh score by spearman’s non-parametric correlation and we found a positive correlation of NLR with all three well-established prognostic markers i.e. Maddrey DF score, MELD score (Figure 4) and Child-Pugh score with a significant p-value <0.05 (Figure 2, Table 4).

A higher NLR (>4.5) in our study was also found to be associated with higher risk of developing complications like HRS (43.2% in

NLR >4.5 vs. 13.8% in NLR <2.5 and 33.3% in NLR 2.5-4.5; p-value 0.0147) (Figure 2). It also showed positive correlation with hepatic encephalopathy and mortality rate although p-value couldn’t reach statistical significance (Figure 2, Table 4). NLR also correlated well with amount of alcohol consumption, with significant rise in heavy drinkers. Thus it can be concluded that NLR can be used as a simple bedside prognostic marker to assess disease severity in alcoholic liver disease.

Conclusions

O u r s t u d y c o n c l u d e s t h a t t h e r e i s a d o s e d e p e n d e n t relation of complications (hepatic e n c e p h a l o p a t h y ) , p r o g n o s t i c markers (DF score, MELD score and Child-Pugh score) and NLR with amount of alcohol intake but type of alcohol exposure don’t have much effect on the complications, prognostic markers and mortality. Duration of alcohol didn’t have an effect on most of the disease severity markers except Child-Pugh score and overall mortality, though age-related bias could not be ruled out when comparing for duration. NLR emerged as a useful bedside marker of disease severity which correlates well with all three prognostic markers, complications like HE and HRS. NLR also correlated with mortality rate although not found to be statistically significant. Further studies with age-matched larger sample may probably throw more light on the effect of alcohol duration and NLR on mortality rates.

References

1. Hozo I, Mirić D, Ljutić D, Giunio L, Andelinović S, Bojić L. Relation between the quantity, type and duration of alcohol drinking and the development of alcoholic liver cirrhosis. Med Arh 1995; 49:5-8. 2. Savolainen VT, Liesto K, Mannikko A, Penttila

A, Karhunen PJ. Alcohol consumption and alcoholic liver disease: evidence of a threshold level of effects of ethanol. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 1993; 17:1112-7.

3. Becker U, Deis A, Sørensen TI, Grønbaek M,

Borch-Johnsen K, Müller CF, et al. Prediction of Risk of Liver Disease by Alcohol intake, Sex, and Age: A prospective population study. Hepatology 1996; 23:1025-9. 4. Sato N, Lindros KO, Baraona E, Ikejima

K, Mezey E, Jarvelainen HA, et al. Sex difference in alcohol-related organ injury.

Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2001; 25:40S– 45S. 5. Furube M, Sugimoto M, Asakura I, Mizukami

H, Akita H, Hatori T, et al. Sex difference in alcoholic liver disease: with special reference to the severity of alcoholic hepatitis. Arukoru Kenkyuto Yakubutsu Ison

1989; 24:135-43.

6. Douds AC, Cox MA, Iqbal TH, Cooper BT. Ethnic differences in cirrhosis of the liver in a british city: Alcoholic cirrhosis in south Asian men. Alcoholism 2003; 38:148-50. 7. Wickramasinghe SN, Corridan B, Izaguirre

J, Hasan R, Marjot DH. Ethnic differences in the biological consequences of alcohol abuse: a comparison between South Asian and European males. Alcoholism 1995; 30:675-80.

8. Narawane NM, Bhatia S, Abraham P, Sanghani S, Sawant SS. Consumption of ‘country liquor’ and its relation to alcoholic liver disease in Mumbai. J Assoc Phys Ind

1998; 46:510-13.

9. Mendenhall C, Roselle GA, Gartside P, Moritz T. Relationship of protein calorie malnutrition to alcoholic liver disease: a reexamination of data from two Veterans Administration Cooperative Studies.

Alcohol Clin Exp Res 1995; 19:635-41. 10. Leevy CM, Moroianu SA. Nutritional aspects

of alcoholic liver disease. Clin Liver Dis 2005; 9:67-81.

11. Sherlock S, Dooley J. Alcohol and the liver. In: Sherlock S, Dooley J, editor. Diseases of the Liver and Biliary System. 11th ed. Oxford: Blackwell science; 2001:381-98. 12. Patek AJ, Toth IG, Saunders MG, Castro

GAM, Engel JJ. Alcohol and dietary factors in cirrhosis. An epidemiological study of 304 alcoholic patients. Arch Intern Med

1975; 135:1053-7.

13. Mendenhall CL. Alcoholic hepatitis. Clin Gastroenterol 1981; 10:417-41.

14. Khan AJ, Husain Q, Choudhuri G, Parmar D. Association of polymorphisms in alcohol dehydrogenase and interaction with other genetic risk factors with alcoholic liver cirrhosis. Drug Alcohol Depend 2010; 109:190-7.

15. Vaswani M, Prasad P, Kapur S. Association of ADH1B and ALDH2 gene polymorphisms with alcohol dependence: a pilot study from India. Hum Genomics 2009; 3:213-20.

16. Bhaskar LVKS, Thangaraj K, Osier M, Reddy AG, Rao AP, Singh L et al. Single nucleotide polymorphism of the ALDH2 gene in six Indian populations. Ann HumBiol 2007; 34:607-19.