Evaluation of the Repayment of Teachers’ Loans Scheme

Patrick Barmby and Robert Coe

Curriculum, Evaluation and Management Centre

University of Durham

Research Report No 576

Evaluation of the Repayment of Teachers’ Loans Scheme

Patrick Barmby and Robert Coe

Curriculum, Evaluation and Management Centre

University of Durham

The views expressed in this report are the authors’ and do not necessarily reflect those of the Department for Education and Skills.

© University of Durham 2004 ISBN 1 84478 312 X

Table of Contents

Executive Summary...i

1. Introduction...1

(a) Introduction ...1

(b) Teacher recruitment...2

(i) Reasons for entering teaching ...2

(ii) Reasons for not entering teaching...3

(iii) Recommendations to improve teacher recruitment ...4

(c) Teacher retention ...5

(i) Reasons for leaving the profession ...6

(ii) Job satisfaction, teacher morale and motivation ...8

(iii) Tackling teacher retention issues ...9

(d) Recent financial incentives...9

(i) Repayment of Teachers’ Loans Scheme ...10

(ii) Teacher Bursaries...10

(iii) Golden Hellos ...11

(iv) Success of financial incentives...11

(e) Summary...13

2. Methodology for the Study...14

(a) Introduction ...14

(b) Methodology ...14

(c) Sampling...15

(d) Interviewing Teachers ...18

3. Findings on Teacher Recruitment...19

(a) Introduction ...19

(b) Background to recruitment issues ...19

(c) Reasons for entering teaching and dissuading factors...20

(d) The relative impact of different financial incentives on teacher recruitment...21

(e) The impact of the Repayment of Teachers’ Loan Scheme on recruitment ...23

(f) Summary ...26

4. Findings on Choosing a Shortage Subject ...27

(a) Introduction...27

(b) Background issues for recruitment into shortage subjects ...27

(c) Improving recruitment into shortage subjects ...28

(d) The relative impact of different financial incentives on recruitment into shortage subjects ...29

(e) The influence of the Repayment of Teachers’ Loan Scheme on the decision to teach a shortage subject rather than a non-shortage subject. ...31

(f) Retaining teachers in shortage subjects...33

5. Findings on Teacher Retention...35

(a) Introduction ...35

(b) Leaving teaching ...35

(c) Suggestions for improving teacher retention...37

(d) The impact of the Repayment of Teachers’ Loans Scheme on teacher retention ...38

(e) Summary...40

6. General Findings Concerning the Scheme ...42

(a) Introduction ...42

(b) How the scheme worked ...42

(c) Areas for improvement...43

(d) The Student Loans Company ...45

(e) Summary...47

7. Conclusions and Future Considerations...48

(a) Introduction ...48

(b) The impact of the Repayment of Teachers’ Loans Scheme ...48

(c) How the scheme worked for teachers...51

(d) General findings concerning teacher recruitment and retention...52

8. References...53

Appendix A: Methodology for the Literature Review...56

Appendix B: Interview Script for the Evaluation...57

Appendix C: Summary of Results...70

(a) Teacher recruitment ...72

(b) Teaching a shortage subject...84

(c) Retaining teachers...92

(d) General views on the Repayment of Teachers’ Loans Scheme ...99

Executive Summary

Introduction1. The Repayment of Teachers’ Loans Scheme was introduced as a pilot initiative by the UK Government in 2002. Designed to attract and to retain teachers in the profession, the scheme is available to Newly Qualified Teachers (NQTs) in both schools and Further Education institutions in England and Wales, qualifying from initial teacher training in 2002, 2003 and 2004.

2. This initiative is paid to teachers once they take up their post in schools. The scheme allows the government to repay the student loans of teachers over a ten-year period. One-tenth of the student loan is repaid for each year that a teacher remains in the profession. If a teacher leaves the profession before ten years, they have only a portion of their loan paid off according to how long they have taught.

3. The evaluation of the Repayment of Teachers’ Loans Scheme was carried out by the University of Durham during January to June 2004. The study was designed to answer the following evaluation questions:

• To what extent were teachers’ decisions to enter teaching influenced by the prospect of having their student loans written off by the scheme?

• Where teachers had a choice of subjects that they could teach, did they choose a shortage subject to enable them to join the scheme?

• Is the prospect of having their loans written off likely to be an important factor in any future decisions on whether to stay in teaching?

4. The evaluation included a literature review of studies involving teacher recruitment and retention, a pilot study, and a main study involving the telephone interviews of 276 teachers about the Repayment of Teachers’ Loans Scheme.

Literature Review

5. A review of literature was carried out in the areas of recruitment and retention. This examined recent studies (1999 onwards) and evolved to encompass 40 sources of information.

6. In general, the literature on teacher recruitment can be divided into three areas:

• reasons why people take up teaching as a career,

• reasons why people are deterred from entering teaching,

• suggestions for improving recruitment into teaching.

In addition, the success or otherwise of financial incentives in terms of recruitment and retention can also be examined.

7. Looking at why people take up teaching in the first place, the most common reasons emerging from the literature were intrinsic or altruistic in nature (e.g. wanting to work with children, perceived job satisfaction, enjoyment of subject and positive experiences of teaching in the past). However, if we look at reasons why people might have been deterred from entering teaching, external considerations appear to have played a more important part (e.g. pay, workload, image and status of teaching, stress, long hours, excessive paperwork and relatively low remuneration and student behaviour).

8. Recommendations from the literature to improve recruitment focused on tackling these extrinsic issues that dissuade people from teaching, for example improving teachers’ pay, improving the image of teaching and tackling workload/paperwork. 9. Workload, pupil behaviour, government initiatives, salary, stress, status/recognition

and career prospects were highlighted in the literature in terms of teachers decisions to leave the profession. School leadership was also highlighted as a key attitudes-influencing factor.

10.Suggestions for tackling teacher retention focused on these various reasons, e.g. reduce workload, improve pupil behaviour and better salary, as well as looking at management and communication issues within schools/colleges.

11.Studies have also been carried out to specifically look at the impact of available financial incentives on recruitment and retention. We can generally conclude from these studies that the training bursary, the Golden Hello and the Repayment of Teachers’ Loans Scheme (although the last two only examined by one study each) appear to have some impact on attracting teachers into the profession.

12.In terms of retention, the Repayment of Teachers’ Loans Scheme seemingly has the potential to persuade teachers to stay in the profession.

Methodology for the Evaluation

13.For the main part of the evaluation, a telephone survey was carried out with a sample of teachers taking part in the Repayment of Teachers’ Loans Scheme, specifically those teaching English, Maths or Science. Teachers of other shortage subjects were not included in this study. The sample included teachers working in Further Education (4% of sample) and also primary specialist teachers (2%) eligible for the scheme.

14.It was intended that at least 200 teachers take part with the sample weighted so that 25% of these were from London. The problem of teacher shortages is more acute in London so this weighting ensured a larger number of teachers from there. 800 letters were sent out to teachers, eliciting a response rate of 39%. Additional sampling was then carried out because the response from teachers had been greater than expected. A reduction in the numbers, in order to carry out the study within the allocated time, resulted in 276 teachers being selected.

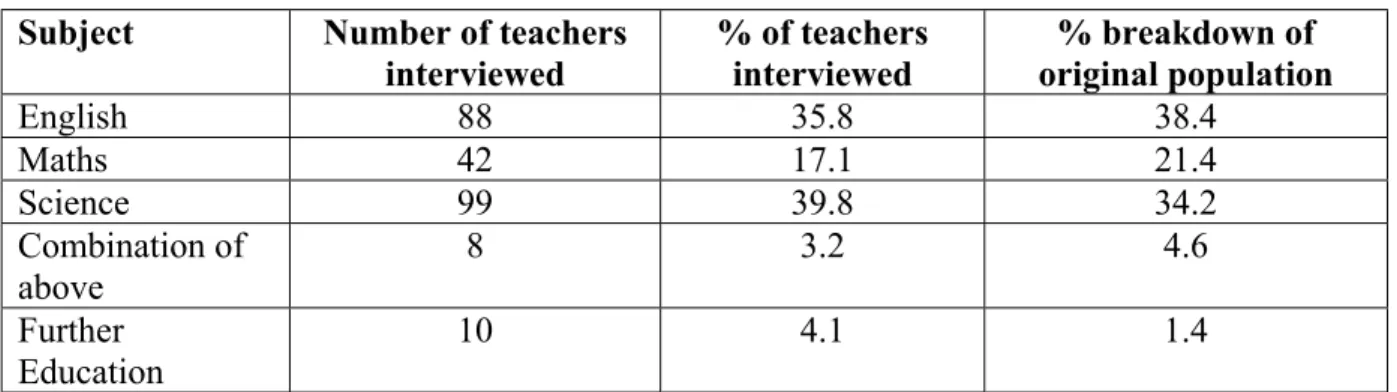

out between 15th March and 23rd April 2004. Of the 276 teachers selected, 26 teachers could not be contacted and 4 teachers withdrew from the study. In total therefore, 246 interviews were successfully completed. This sample of teachers, taking part in the Repayment of Teachers’ Loans Scheme and chosen to take part in the study, had a similar breakdown to the original population of teachers in the scheme, in terms of female/male split and location around the country (including the 25% weighting towards London).

16.The interviews with teachers addressed the following key questions:

• The impact of the scheme, and of financial incentives, on their decision to enter teaching.

• The impact of the scheme, and of financial incentives, on their decision to teach a shortage subject rather than other subjects.

• The likely influence of the scheme, and of other financial incentives, on future decisions on whether to remain in teaching.

• Their general views on the Repayment of Teachers’ Loans Scheme.

In examining these areas, both quantitative (e.g. rating the importance of the scheme in one of the above areas) and qualitative responses (e.g. explanation of reasons for the success or otherwise of the scheme) were elicited from teachers.

Teacher Recruitment

17.Examining teachers’ reasons for entering teaching in the first place, the findings of the present study were largely in line with the other studies described in the literature review, concurring that the reasons for going into teaching were largely altruistic or intrinsic in nature. When asked to rate the importance of different motivating factors in attracting them into teaching, reasons such as ‘Helping children to succeed’, ‘Mentally stimulating work’, ‘Job satisfaction’ and ‘Imparting knowledge to pupils’ were rated as the most important by teachers. Reasons associated with finances (‘Financial incentives’ and ‘Salary’) were rated as less important by teachers.

18.When teachers were asked separately in a more open-ended question why they went into teaching in the first place, the most frequent responses were the same intrinsic/altruistic reasons as above. However, additionally, teachers also stated that they ‘always had it in mind’ to go into teaching or had enjoyed their previous experiences of teaching.

19.When asked what might have dissuaded them from entering teaching, financial considerations such as salary and cost of training were third and fourth in terms of the number of times they were cited by teachers. The most often cited issues however concerned pupil behaviour and workload/marking.

20.Asked to rate the importance of different financial incentives in attracting them into teaching, 84% of teachers rated teaching bursaries as ‘quite important’ or ‘very important’, compared with 49% for Golden Hellos and 38% for the Repayment of Teachers’ Loans Scheme. Furthermore, in answer to the question ‘to what extent do you think this scheme has influenced your decision to enter teaching?’, 78% of the

teachers stated that it had not influenced them at all and 19% of the teachers stated that it had influenced them to some degree.

21.Examining the details of these responses, the main problem was found to be that teachers did not know about the Repayment of Teachers’ Loans Scheme before they had entered into teaching. As a result, when asked whether they still would have entered teaching if the scheme had not been available, only 9% of the teachers stated that they would not have entered or that the scheme had had some influence.

22.The difference in this figure of 9% to the previous figure of 19% (point 20) is because some of the influence of the scheme in the 19% figure took the form of reducing worries for teachers or the scheme being a bonus. In terms of specifically influencing teachers to enter the profession therefore, we take the second figure of 9% as being more accurate.

23.Conversely though, when teachers were asked whether the scheme was generally a good idea for recruiting teachers, only a small number (7%) disagreed that this might be the case. Teachers highlighted that the scheme helped reduce financial worries, especially for recent graduates leaving university with large debts.

24.Some concerns were raised though that the scheme could attract people into teaching for the wrong reasons. Also, teachers highlighted the fact that the scheme needed advertising more. We therefore concluded that if the drawbacks of the scheme are tackled, especially in the way it is publicised, the scheme does have the potential to attract teachers into the profession.

Choosing a Shortage Subject

25.Examining the choice made by teachers to go into shortage subjects specifically, only 46 out of the 246 teachers interviewed (19%) stated that they had a choice of whether or not to teach a shortage subject in the first place. Therefore, in considering the impact of financial incentives on making this choice, we must bear in mind that only a small proportion of teachers were in a position to choose in the first place.

26.10 out the 46 teachers who had a choice (22%) said that they had made a choice influenced by financial incentives generally (rather than specifically the Repayment of Teachers’ Loans Scheme).

27.When teachers were asked how recruitment into shortage subjects could be improved, salaries and financial considerations were still the most frequently mentioned suggestions, indicating that incentives could be a relatively successful way of attracting people into shortage subjects.

28.When asked to rate the importance of various financial incentives in attracting people into shortage subjects, the percentages of teachers rating schemes as ‘quite important’ or ‘very important’ were 82% of teachers for Golden Hellos, 82% again for the Repayment of Teachers’ Loans Scheme and 89% for financial incentives generally. Furthermore, in answer to the question ‘do you think that the Repayment of Teachers’ Loans Scheme is a successful way for attracting people into shortage subjects?’, only

11% of the teachers disagreed.

29.However, when the 46 teachers who had a choice of teaching a shortage subject were asked whether the Repayment of Teachers’ Loans Scheme specifically had influenced their decision, only 6 teachers (13%) stated that it had been of some influence. Once again, the issue of not knowing about the scheme to begin with was highlighted by teachers.

30.Teachers were also asked whether the scheme had been an important consideration in deciding whether to continue to teach a shortage subject, as opposed to moving into other subjects to teach. Taking into account problems with the phrasing of the questions to teachers, we estimated that 15% of those surveyed were influenced by the scheme in this way.

Teacher Retention

31.When asked to rate the importance of possible suggestions for persuading teachers to remain in teaching, reasons such as ‘Support on pupil discipline’ and ‘Reduce teacher workload’ were rated the most important. Financial incentives, although felt to be ‘quite important’ for improving teacher recruitment, were not perceived to be as important as other suggestions.

32.Asked to rate the importance of the Repayment of Teachers’ Loans Scheme specifically in retaining them into teaching, 35% of teachers rated the scheme as ‘quite important’ or ‘very important’. One might recall that 38% and 82% of the teachers previously gave similar ratings to the impact of the scheme on recruitment generally and the choice of shortage subjects.

33.In answer to the question ‘was the scheme an important consideration for you in deciding whether or not to stay in teaching?’, 44% of the teachers disagreed. Of those disagreeing, teachers highlighted that the ‘debt was not large enough to be a consideration’, that they ‘could see myself leaving anyway’, that they ‘would leave if I was unhappy’ and that the scheme was ‘not the most important consideration’.

34.Amongst those interviewed, 68 teachers (28%) stated that they thought that they would be leaving teaching sometime in the next ten years. Of the 175 teachers that planned to stay in teaching, 26 teachers stated either that they would not have decided to stay in teaching or were not sure whether they would have stayed if the scheme had not been available. Therefore, we made the assumption that the scheme persuaded 26 out of the total of 246 teachers, or 11% of teachers, to remain in teaching. As we cannot attribute this small degree of influence to lack of prior knowledge about the scheme, we concluded that the scheme seemed to have the least impact in this area of teacher retention.

General Comments

35.When asked to generally comment on the Repayment of Teachers’ Loans Scheme, the majority of the teachers surveyed were positive about the scheme, stating that it had

worked well or that it was a good scheme. However, there were a number of suggestions made by teachers to improve the scheme overall:

• Advertise the scheme more and target potential teachers.

• Provide clearer and more accessible information about the scheme.

• Simplify the application process and forms.

• Clarify and speed up the acceptance process so that teachers do not need to make payments.

• The Student Loans Company to examine how it can improve the service it provides to teachers e.g. provide more and clearer statements of how much of the loans have been paid off, simplify the annual renewal process and job-changing process.

Conclusions and Future Considerations

36.Overall, if we take into account the overlap of those influenced by the scheme in terms of recruitment, choosing shortage subjects and retention (e.g. one teacher can be influenced to go into teaching and to stay in teaching by the scheme), we estimate that the scheme impacted in some way on 76 of the 246 teachers surveyed, or 30% of the teachers. This was despite the shortcomings of the promotion of the scheme. We can therefore take this figure as an indication of the overall influence of the scheme on those surveyed.

37.Based on the findings of the evaluation therefore, the following issues are put forward for consideration by the DfES:

• Further consideration should be given to the marketing strategy to ensure that it is advertised and promoted effectively, and reaches key audiences. The DfES should re-evaluate the impact of the scheme on recruitment when this has been addressed.

• It is proposed that financial incentives in general are an important way of attracting teachers, particularly into shortage subjects.

• The present scheme was least effective though in its impact on retention (although the scheme did have an impact on 11% of the teachers with regards to retention). It is recommended that the DfES continues to explore other ways to tackle the issue of teacher retention.

• That the DfES and the Student Loans Company examine the operational issues highlighted in this report, to try and reduce the difficulties experienced by some teachers taking part in the scheme.

1. Introduction

In this chapter, we examine• The general background to teacher recruitment and retention.

• The findings of previous studies on teacher recruitment.

• The findings of previous studies on teacher retention.

• The background to and perceived success of recent financial incentives.

(a) Introduction

A shortage of teachers, especially in particular areas of the country and in particular subjects, continues to be a major issue for the UK education system. At the beginning of the 1990s, Grace (1991), in her discussion of the problems faced by the education system in England and Wales, highlighted the concerns of the Select Committee for Education (1990) that the number and quality of applicants for teaching posts had been declining. In particular, ‘many schools have difficulty providing properly qualified teaching in mathematics, physics, design and technology and modern languages, and also in religious education, early years education and business studies.’ Also, ‘regional problems in teacher supply were also apparent and “the seriousness of the current situation on London” was noted’. As we approached the end of the decade and moved into the new century, these areas of major concern seemingly remained so. In his comparison of teacher shortages in England and Scotland, Menter (2002) recognised that

“The vacancies and shortages are not evenly spread. Particular geographical regions experience exaggerated shortages (e.g. London), while others may have almost a full complement (e.g. the Yorkshire and Humberside region had a vacancy rate of 0.3 compared with a London rate of 3.3 in 1999/2000). There are also shortages in particular subjects, maths, modern foreign languages, design and technology, science and recently English have all been designated ‘shortage subjects’ by the TTA.”

More recently, the proposed introduction of higher tuition fees by the government has raised the fear that this will further impact on the future supply of teachers (BBC News, 2004). Therefore, the issue of teacher recruitment, and how to tackle it, remains just as important as it has been in the past.

To tackle this long-standing problem, the call was made by Sir Stewart Sutherland (1997) in the Dearing report into Higher Education to ‘undertake an assessment of the effectiveness of the current arrangements for recruitment and the desirability of introducing a wider range of incentive measures to improve recruitment in priority subject areas’. He also suggested that ‘further work should be undertaken to establish more accurately the reasons for, and responses to, wastage.’ Focussing therefore on these two areas of teacher recruitment and teacher retention, there are large amounts of literature on these topics (for example, recent literature review by Spear, Gould and Lee (2000)). In addition, there have been a number of

recent government initiatives to tackle teacher recruitment; for example (from Menter, 2002),

• Financial incentives such as training salaries, Golden Hellos;

• Major advertising campaigns;

• Targeted recruitment drives (e.g. at men and minority ethnic members);

• Promotion of part-time and distance-learning routes into teaching;

• Establishment of the Fast Track Teaching Programme;

• School-centred initial teacher training (ITT) schemes;

• Employment-based training routes, and

• Recruitment Managers based in Local Education Authorities.

Therefore, in this introduction to the report, we begin by highlighting the background and context to the Repayment of Teachers’ Loans Scheme, in particular focusing on recent research that has been carried out into teacher recruitment and retention. We then go on to describe the Repayment of Teachers’ Loans Scheme and other recent financial incentives, discussing whether these initiatives appear to impact on recruitment and retention.

(b) Teacher Recruitment

1Figures published by the DfES (2004) indicate that there has been a recent improvement in teacher vacancy rates (as a percentage of teachers in post) in England. In 2004, the vacancy rate was 0.5 in nursery and primary schools, compared to the high of 1.2 in 2001. In secondary schools, the rate of 0.9 in 2004, compared with 1.4 in 2001, also indicates a reduction in teacher vacancies. However, although the recent rate for nursery and primary schools is the lowest since 1997, the rate for secondary schools remains high compared to the rates of 0.4 to 0.7 occurring in 1997 to 2000.

One of the factors that has impacted on teacher vacancy rates is the number of new entrants into the profession. Once again, figures from the DfES (2003) are encouraging. Looking at the numbers of people that enrolled on Initial Teacher Training courses, there was a steady rise from 13,870 in 1999/2000 to 18,300 in 2003/04. This optimism though must be tempered by the number of teachers leaving the profession. We will examine the issue of teacher retention in due course. However, in this section, we will concentrate on what the recently published literature says on the issue of teacher recruitment.

(i) Reasons for entering teaching

The literature on teacher recruitment has looked at three broad areas; reasons why people took up teaching as a career, reasons why people have been deterred from entering teaching and suggestions for improving recruitment into teaching. Looking firstly at the reasons for entering teaching, we found that these reasons were themselves sub-divided into types of reasons why someone would enter teaching. Kyriacou and Coulthard (2000) identified that

1 The background on teacher recruitment, retention and the success of recent initiatives was collected as part of a

literature review at the beginning of this evaluation. Details of the how the literature review was carried out are provided in Appendix A of this report.

the ‘main reasons for choosing teaching as a career fall into three main areas:

(1) altruistic reasons: these reasons deal with seeing teaching as a socially worthwhile and important job, a desire to help children succeed, and a desire to help society improve;

(2) intrinsic reasons: these reasons cover aspects of the job activity itself, such as the activity of teaching children, and an interest in using their subject matter knowledge and expertise; and

(3) extrinsic reasons: these reasons cover aspects of the job which are not inherent in the work itself, such as long holidays, level of pay, and status.’

Moran et al. (2001) suggested that ‘not all of these three factors may affect the motivation of an individual, that each factor may carry a different emphasis and that there may be gender differences’. Their analysis of relevant literature concluded that ‘the reasons for choosing the teaching profession as a career have been predominantly altruistic and intrinsic, although extrinsic rewards could take precedence’. This conclusion was also born out by other studies. Carrington and Tomlin (2000), in their survey of 289 PGCE students from ethnic minority backgrounds, specifically stated that the ‘trainees tended to stress the importance of intrinsic (rather than extrinsic) considerations when describing their reasons for wanting to teach or, alternatively, emphasised the social dimensions of teaching (e.g. likes working with people, including children)’. Looking at individual reasons for wanting to teach, the most frequently stated reasons in recent studies were indeed intrinsic/altruistic in nature: wanting to work with children (Johnston, McKeown and McEwen, 1999a, Moran et al., 2001, Smithers and Robinson, 2001, Thornton and Reid, 2001, Thornton, Bricheno and Reid, 2002), perceived job satisfaction (Johnston, McKeown and McEwen, 1999b, Thornton and Reid, 2001, Thornton, Bricheno and Reid, 2002), enjoyment of subject (Kyriacou and Benmansour, 1999) and positive experiences of teaching in the past (Hammond, 2002). The only extrinsic reason that emerged from any of the studies as the most cited reason to enter into teaching was ‘long holidays’ (Kyriacou and Coulthard, 2000, Rawlinson et al., 2003), although Donnelly (2000) found during the interviewing of teachers in Yorkshire that ‘no more than 10 per cent of those interviewed had held any long-term intention to enter teaching. The large majority had entered because it had suited their circumstances.’

(ii) Reasons for not entering teaching

Financial considerations such as salary were only ranked within the top few reasons for going into teaching in two studies (Johnston, McKeown and McEwen, 1999b, Rawlinson et al., 2003). Therefore, when considering the reasons why people entered into teaching, we could conclude that financial considerations, and indeed extrinsic reasons in general, did not play an important part. However, this is only half the story. If we instead look at reasons why people did not choose to go into teaching, we see that external considerations play a more important role. In their interviews of 148 prospective primary teachers, Thornton, Bricheno and Reid (2002) found that pay was the thing that could most discourage people from becoming teachers, followed by workload and then the image and status of teaching. Likewise, Carrington and Tomlinson (2000) found in their survey of PGCE students that they ‘perceive the job as involving considerable stress, long hours, excessive paperwork and relatively low remuneration.’ Undergraduate students in geography, in the study by Rawlinson et al. (2003), identified pay, student behaviour, stress, government attitude, low morale and long hours as deterrents to enter into teaching. Another study of undergraduates,

this time at York University by Kyriacou and Coulthard (2000), identified dealing with disruptive pupils, the amount of bureaucratic tasks, school funding, OFSTED inspections, the government’s commitment towards education and the media image of teachers as factors that discouraged people from teaching. When considering the recruitment of teachers into the profession therefore, it is important to consider this tension between largely intrinsic or altruistic factors which are attracting people into teaching, and what appear to be largely extrinsic reasons that dissuade people from entering the profession. This tension was highlighted by Scott, Cox and Dinham (1999) in their study of the motivation and satisfaction of teachers.

“Whilst teachers rate themselves dissatisfied overall with their profession, they remain satisfied with some aspects of it. The ‘core business’ of teaching – working with students and seeing them achieve, and increasing one’s own professional skills and knowledge – remain very satisfying for most teachers. Most dissatisfying in contrast were systematic or societal factors – the pace of educational change and the increase in workload associated with it, and the continuing devaluing and criticism of the teaching service.”

That we have witnessed problems in teacher recruitment may be an indication that these ‘dissuading’ factors are having more of an impact for people than the ‘persuading’ factors to enter into teaching. We see this in the study by Kyriacou and Coulthard (2000) where undergraduates rated the factors ‘a job that I will find enjoyable’, ‘colleagues that I can get along with’ and ‘pleasant working environment’ as the most important factors for a job, although they perceived that these were fairly low down the order when it came to rating whether teaching offered particular factors. Likewise, Kimbell and Miller (2000) in their study of the attitude of potential Design and Technology teachers found that the students’ views of teaching - when contrasted with their ideal job - was that it lacked variety, professional freedom and creativity. It was also poorly paid and lacked career fast tracks (although the DfES subsequently introduced the Fast Track Teaching Programme in 2001).

(iii) Recommendations to improve teacher recruitment

Having identified this tension between reasons to enter and reasons not to enter teaching, what recommendations did the literature provide for tackling the problem of teacher recruitment? It would seem sensible that any recommendations would tackle the largely extrinsic issues that dissuade people from entering teaching, and this is what we found in the literature. Improving teachers’ pay was a frequently made recommendation in recent studies (Kimbell and Miller, 2000, Kyriacou and Coulthard, 2000, Thornton and Reid, 2001, Thornton, Bricheno and Reid, 2002, Rawlinson et al., 2003), as was improving the image of teaching and tackling workload/paperwork (Kimbell and Miller, 2000, Thornton and Reid, 2001, Thornton, Bricheno and Reid, 2002). Better resources for teaching and improvements in the working environment were also suggested (Kyriacou and Coulthard, 2000), as well as increased autonomy and more creativity for teachers (Kimbell and Miller, 2000).

(c) Teacher Retention

Whilst the teacher recruitment figures paint an optimistic picture, there have been ongoing concerns about teacher retention. Past statements made by those associated with the UK Government indicated a serious concern about those teachers leaving the profession during the early stages of their career:

‘The proportion of new teachers leaving within three years has remained fairly constant at around 23% over the last 5 years’. - Parliamentary statement from Estelle Morris (Slater, 2001)

‘Most recently attention has focused on the retention of teachers in the early stages of their careers, with Her Majesty’s Chief Inspector of Schools, Mike Tomlinson, suggesting that 40% of Newly Qualified Teachers (NQTs) have left teaching within three years.’ (Menter, 2002)

This situation may be more serious when we take into account those that do not even make it into the classroom in the first place. Smithers and Robinson (2001) estimated that 12% of those admitted onto teacher training courses did not successfully complete, that 40% of those on the final year of courses did not make it into the classroom and a further 18% left during the first three years of teaching. Recent figures from the DfES (DfES, 2003) showed that of those completing initial teacher training courses in 2001 in England and Wales, 21% of those were not in service by March 2002. There were wide regional variations in these figures as well, varying from 14% not being in service in the East Midlands to 36% in Wales.

The figures for new entrants must therefore be taken in context with the figures for those leaving the profession. Turning once again to recent figures from the DfES (DfES, 2003), we find that the numbers entering the profession (within maintained schools) have in fact exceeded the numbers leaving the profession over recent years:

Table 1.1: Numbers entering the teaching profession and the ‘wastage’ of teachers (in England only)

Year Total Entrants to full-time teaching2

Total Movement away from full-time teaching3

Balance (Entrants – Wastage) 1991-92 24,720 26,540 -1,820 1996-97 27,730 27,330 400 1997-98 29,080 29,470 -390 1998-99 27,550 24,260 3,290 1999-00 29,400 25,230 4,170 2000-01 31,010 25,850 5,160 2001-02 33,220 27,870 5,350

Although the numbers leaving the profession have been less overall than those entering the

2 These figures include Newly Qualified entrants, those new to the maintained sector and those returning to the

maintained sector.

3 This includes those who had retired, and also out of service teachers who were no longer in the maintained

profession, we see once again a regional variation. For example, the wastage rate in London and in the South East in 2000-01 was 9.8%, compared to 6.7% in the North East. Looking at overall vacancy rates (compiled from DfES, 2003, DfES, 2004 and National Assembly of Wales, 2004) in maintained schools in England and Wales,

Table 1.2: Vacancy rates4 in maintained nursery and primary schools by Government Office region

Vacancies as a percentage of teachers in post

Region 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004

North East 0.4 0.4 0.5 0.3 0.6 0.6 0.4 0.3

North West 0.3 0.3 0.3 0.3 0.4 0.5 0.3 0.3

Yorkshire and the Humber 0.1 0.4 0.2 0.3 0.3 0.8 0.3 0.3

East Midlands 0.4 0.5 0.4 0.6 0.7 0.5 0.3 0.3 West Midlands 0.2 0.4 0.7 0.6 0.7 0.8 0.5 0.4 East of England 0.7 0.7 0.8 0.9 1.7 1.6 0.8 0.6 London 1.7 2.5 2.3 2.0 3.3 2.4 1.7 1.0 South East 0.8 0.8 0.8 1.0 1.6 1.1 0.8 0.4 South West 0.5 0.6 0.4 0.7 0.6 0.4 0.3 0.3 Wales 0.5 0.8 0.4 0.2 0.3 0.2 0.3 0.3

Table 1.3: Vacancy rates in maintained secondary schools by Government Office region Vacancies as a percentage of teachers in post

Region 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004

North East 0.3 0.4 0.5 0.4 1.0 0.7 0.9 1.0

North West 0.3 0.2 0.2 0.3 0.6 0.6 0.6 0.7

Yorkshire and the Humber 0.2 0.4 0.1 0.3 0.6 1.0 0.9 0.7

East Midlands 0.2 0.4 0.3 0.4 0.6 1.1 0.6 0.6 West Midlands 0.4 0.5 0.4 0.5 1.1 1.4 1.0 1.0 East of England 0.4 0.7 0.7 0.8 1.7 1.8 1.4 1.0 London 1.0 1.3 1.4 1.8 3.8 2.9 2.2 1.6 South East 0.5 0.6 0.7 1.0 2.1 1.6 1.6 1.0 South West 0.3 0.3 0.3 0.5 0.7 0.5 0.4 0.4 Wales 0.3 0.5 0.7 0.3 0.5 0.6 0.6 0.5

Although in general there has been a reduction in teacher vacancy rates over recent years, the figures for London remain higher than in the other Government Office Regions.

(i) Reasons for leaving the profession

What then are the possible reasons for people leaving the teaching profession and why might retention be more of an issue in areas such as London? The review by Spear, Gould and Lee (2000) provided some background on this and examined this question from two standpoints; why practicing teachers chose to leave teaching and also why teachers chose to take early retirement. The reasons cited in past studies by teachers for leaving the profession or for

4 Advertised vacancies for full-time permanent positions (or appointments of at least one term’s duration),

dissatisfaction with their jobs included

• lack of success in teaching,

• status of teachers,

• pupil motivation/discipline,

• financial reward/salary,

• promotion prospects/career opportunities,

• workload/increased administration,

• resources/work conditions,

• personal satisfaction,

• loss of autonomy,

• teaching outside one’s subject,

• morale of colleagues,

• childcare/domestic commitments,

• change in personal circumstances such as moving to different area, illness or early retirement,

• disillusionment caused by, for example, dissatisfaction, stress, low morale, lack of support.

The reasons cited from past studies for early retirement were

• demands for accountability,

• demands for improved personal performance,

• changes in society’s view of the role of schools,

• workload,

• paperwork,

• lack of support from local authority advisers,

• increased governor power,

• increased parent power,

• increased staff power,

• pupil behaviour,

• changes in the education system.

Spear et al. concluded that all of the above contributed to the rising incidence of stress amongst teachers.

Looking at the reasons put forward in more recent studies for leaving teaching, workload, government initiatives and stress were the three most important reasons highlighted by Smithers and Robinson (2003). In the study of mature students entering teaching by Whitehead, Preece and Maughan (1999), heavy workload, classroom management and insecurity due to possible redundancy were highlighted as issues of concern. Smithers and Robinson (2001) highlighted that the resignation rate amongst younger teachers (6.1% for under 25s to 6.3% for 30 to 34 year olds) was higher than for older age groups (5.1% for 35-39 year olds to 1.8% for 50-59 year olds). MacDonald (1999) further explained this issue:

‘One key variable is the point in teachers’ careers and/or their age when attrition occurs. Literature suggests that attrition rates are highest in the early years of the career when … many teachers are moving from survival and discovery to stabilisation and, in their personal life, involved with

family-related changes such as marriage and child rearing.’

Hutchins et al. (2000) looked specifically at the issue in London. The reasons given in their study of teachers leaving the profession were issues with school management, hours worked and pupil behaviour, followed by lack of promotion prospects, school resources, too many responsibilities and pay.

(ii) Job satisfaction, teacher morale and motivation

In addition to looking at specific reasons why people are choosing to leave the teaching profession, we also considered the related areas of job satisfaction, morale and motivation amongst teachers. We can see from the list of reasons cited above by Spear, Gould and Lee (2000) that these three areas come into consideration when we discuss teacher retention. In fact, the review by Spear, Gould and Lee devoted specific chapters to the areas of job satisfaction and teacher morale.

The following definitions were provided for morale and job satisfaction (Evans, 1997) and motivation (Evans, 2000):

Morale: “A state of mind determined by the individual’s anticipation of the extent of satisfaction of those needs which s/he perceives as significantly affecting her/his total work situation”.

Job satisfaction: “A state of mind determined by the extent to which the individual perceives her/his job-related needs to be being met”.

Motivation: “A condition, or the creation of a condition, that encompasses all of those factors that determine the degree of inclination towards engagement in an activity”. We can see that we have the ‘push’ or the motivation to continue with teaching, how teaching meets the perceived needs of an individual in job satisfaction, and how it is perceived that needs will be met in morale. Based on these definitions, it is easy to see why these considerations would be related to teacher retention.

Evans (2001) found ‘morale, job satisfaction and motivation to be influenced much less by externally initiated factors such as salary, educational policy and reforms and conditions of service, than by factors emanating from the more immediate context within which teachers work: school-specific or, more precisely, job-specific factors. As a result, leadership emerged as a key attitudes-influencing factor. Underpinning this, three factors were highlighted as being influential upon morale, job satisfaction and motivation: realistic expectations, realistic perspective and professionality orientation.’ The expectations that a teacher has, the perspective that they come from and the particular knowledge, skills and procedures that define the professionality of a teacher was used to explain why morale, satisfaction and the motivation of teachers could vary such a lot from case to case (Evans, 2000). For example, issues that could bring about a resignation for one teacher could be minor issues for another teacher. Within this diversity of responses, it was identified that ‘institutional leadership and management can do much to foster positive job-related attitudes by helping to create and sustain work contexts that are conducive to high morale, job satisfaction and motivation’ (Evans, 2001).

Hood (2001) also identified that ‘leadership, through staff empowerment and human resource development, is the means of encouraging the formation of the necessary collaborative cultures which will facilitate the motivation of staff’. Jones (2002) identified ‘paperwork, over-regulation, planning and testing’ as negative issues impacting on teacher morale, while the survey of the quality of working life amongst teachers by NFER (Sturman, 2002) identified the dissatisfaction with salaries for teachers and that job commitment was affected by the levels of job satisfaction and stress amongst teachers.

(iii) Tackling teacher retention issues

What suggestions then does the literature have for tackling the problems associated with teacher retention? As one would expect, the suggestions made in the literature were associated with the reasons given above for leaving the profession or bringing about problems with job satisfaction, morale or motivation. Smithers and Robinson (2001), in their interviews with 102 teachers that had resigned from the profession, found that reduced workload, improved pupil behaviour and better salary were most likely to tempt the teachers back into the profession. These inducements were once again identified in a later study by Smithers and Robinson (2003), although the way the school is run was also identified as a possible suggestion. Davies and Owen also found in their survey of FE staff (Davies and Owen, 2001 and Owen and Davies, 2003) that management/management style and communication/consultation/involvement were the two most important factors that ‘would improve the culture of the college’. In their study of the situation in London, as well as identifying better pay as the most important inducement to return to teaching, Hutchings et al.

(2000) identified availability of appropriate work nearer to home, availability of part-time work, possibility of job share, more effective child care and assistance with housing as other inducements to return to teaching.

(d) Recent Financial Incentives

Having described in detail the recent findings on teacher recruitment and retention, let us now describe the main financial incentives that are being used for recruitment and retention, namely Teacher Bursaries, the ‘Golden Hellos’ and of course the Repayment of Teachers’ Loans Scheme. Training bursaries and Golden Hellos were introduced in March 2000 by the then Education and Employment Secretary David Blunkett, in a move to attract more graduates into teacher training5. The piloting of the Repayment of Teachers’ Loans Scheme was announced in the Schools Green Paper (DfES, 2001).

“We want to make teaching still more attractive, by giving extra support to those who commit to it as a career. For shortage subject and areas of difficulty in recruitment, we will explore a scheme to assist new teachers who enter and remain in employment in the state education sector to pay off, over a set period of time, their student loans.” (p.68, DfES, 2001)

5 DfES press notice “GRADUATES TO GET £150 A WEEK TRAINING SALARIES IN £70m

PROGRAMME TO BOOST TEACHER RECRUITMENT”, available at http://www.dfes.gov.uk/pns/DisplayPN.cgi?pn_id=2000_0140

We describe the details of each of these financial incentives below.

(i) Repayment of Teachers’ Loans Scheme

The Repayment of Teachers’ Loans Scheme was introduced as a pilot initiative by the Government in 2002. Designed to attract and to retain teachers in the profession, the scheme is available to Newly Qualified Teachers (NQTs) in both schools and Further Education institutions in England and Wales, qualifying from initial teacher training in 2002, 2003 and 2004. In order to be eligible for the scheme teachers must be:

• Employed in a teaching post at a maintained school, non-maintained special school, a City Technology College, an Academy or in an FE institution.

• Employed to teach one or more of the designated shortage subjects.

• Employed to work for a minimum period of eight continuous weeks (including full- or part-time teachers).

• Have obtained Qualified Teacher Status (QTS) on or after February 2002.

• Go into a teaching post no later than seven months after obtaining QTS (although maternity concessions made).

• Have a loan with the Student Loans Company.

Priority or shortage subjects, for the purposes of the Repayment of Teachers’ Loans Scheme and also the Golden Hello, are defined to be

• Construction

• Design and technology

• Engineering

• English (including drama)

• Information and communications technology

• Mathematics

• Modern languages

• Science

• Welsh

• Basic Skills – defined as literacy, numeracy or English as a second language (applies to teachers who started their first teaching post on or after 1 September 2003)

This initiative is paid to teachers once they take their post in schools. The scheme allows the government to repay the student loans of teachers over a ten-year period. One-tenth of the student loan is repaid for each year that a teacher remains in the profession. If a teacher leaves the profession before ten years they will have only a portion of their loan paid off according to how long they have taught.

(ii) Teacher Bursaries

Training bursaries (also formerly known as training salaries) are paid to trainee teachers during their period of initial teacher training. This bursary amounts to £6000 during their training and is eligible to those undertaking the following courses:

• One-year full-time postgraduate courses

• Two-year full-time postgraduate courses

• Part-time postgraduate courses

• Flexible postgraduate courses

• Postgraduate courses of School-Centred Initial Teacher Training (SCITT)

Therefore, trainees need to be graduates to be eligible. Those on the Graduate Teacher Programme (GTP), taking an employment-based route into teaching, are not eligible for the bursary. Rather, they receive a salary from their school that is at least equal to the minimum point on the unqualified teacher scale (£13,266).

(iii) Golden Hellos

Golden Hellos are available to Newly Qualified Teachers (NQTs), with a PGCE in eligible priority subjects and who are teaching the subject in which they trained in a maintained school. The incentive is £4,000 (taxable) and is paid to teachers after successfully completing their induction year. Supply teachers are also eligible for Golden Hellos on the same terms as permanent teachers, provided that their contract with a school or LEA is of at least one term’s duration. Teachers who gained Qualified Teacher Status through employment-based routes such as Graduate Teacher Programme are not eligible for this incentive.

(iv) Success of financial incentives

Although the literature is not extensive, there are some studies that have looked at the success of financial incentives in recruiting and retaining teachers.

There is some evidence that training bursaries have an impact on teacher recruitment. The Times Educational Supplement reported that following the introduction of the scheme, applications to teacher training were up by 1,100 compared to the same period the year before (Campbell, 2000). These bursaries also produced a jump in the numbers of enquiries from men and ethnic minorities, two target groups for the teaching profession (Barnard, 2000). Howson (2001), looking at applications to and enrolment onto ITT courses in mathematics, found that ‘the evidence from (the training bursaries’) first full year would seem to be positive, at least as applications are concerned. However, with the transfer of the cost of higher education from the State to the individual, any training course will have to compete both with a student’s desire to minimise their existing levels of debt and their views of teaching as a career’. Menter (2002) also identified limited successes for the scheme, with ‘at least a short term improvement in the number of entrants into training’, but particular shortages in areas such as London being ‘resistant to treatment’. Smithers and Robinson (2001) identified the fact that although applications to ITT courses were up by 17.5% due to financial incentives such as the bursary and the Golden Hellos, admissions to courses were up by only 5.5%. When asked about the training bursary, 15 ICT trainee teachers in the study by Hammond (2002) reported that

“No one in the group had felt that the bursary was large enough in itself to attract them into teaching. Most felt they have still to make sacrifices to take

the course, for example some had had to live with parents or, in the words of one, ‘agree to take one step backwards financially to move two steps forward in the future’. Not surprisingly, all were in favour of the bursary, but its impact was evenly divided. Five said they would have done the course without the bursary, five said they could not have done so and five were unsure. One said they had explicitly chosen to do ICT rather than business studies as that was not a shortage subject and three others felt it had played a part in their decision.”

Hutchings et al. (2000) also reported similar problems for London-based NQTs, facing, with the introduction of student loans, the possibility of large debts proving a disincentive to living in an expensive area.

An evaluation of the Golden Hello initiative amongst Further Education teachers (Hopwood, 2004) concluded that 54% of the teachers surveyed felt more valued and 30% felt more motivated as a result of the initiative. In terms of recruitment and retention, 60% of the FE teachers agreed that ‘Golden Hellos are an effective incentive in improving recruitment and retention’. However, looking at the actual impact of the scheme on teachers themselves, only 10% of the teachers felt that the scheme had influenced them to work in FE, and 31% felt that it had had an effect on them to stay in FE. One of the problems raised in terms of recruitment was that most of the teachers found out about the scheme through ‘word of mouth’, calling into question the marketing of the initiative. In terms of retention, qualitative evidence suggested that the scheme would not tackle existing problems, as there were more important issues such as low pay that needed to be considered.

Finally, moving on to the Repayment of Teachers’ Loans Scheme itself, Ivins (2003) looked at the views of undergraduate students concerning financial incentives, including the Loans Scheme, in the context of teacher recruitment and retention. She found that 31% of the 740 students surveyed felt that both the training bursary and the Repayment of Teachers’ Loans Scheme would be the strongest financial incentive to do a PGCE, compared to 17% who felt that better pay structure was a more important incentive and 8% who felt that the Golden Hellos were more important. About 40% of those surveyed stated that the Repayment of Teachers’ Loans Scheme had some impact on the likelihood of them going on to do a PGCE. Looking at the views of 187 PGCE students concerning the scheme, she also found that 33% of those surveyed felt that if they were thinking of leaving teaching, the Repayment of Teachers’ Loans Scheme would persuade them to stay in place.

Generally then, what we can generally conclude from looking at the recent initiatives is that the training bursary, the Golden Hello and the Repayment of Teachers’ Loans Scheme (although the last two only examined by one study each) appear to have some impact on attracting teachers into the profession. In the case of the Golden Hellos though, the lack of prior knowledge about the scheme reduced its impact. In terms of retention, the Repayment of Teachers’ Loans Scheme seemingly has the potential to persuade teachers to stay in the profession. However, for the Golden Hellos, the incentive was not as important as other issues affecting retention. Therefore, for the present evaluation of the Repayment of Teachers’ Loans Scheme, these issues of knowledge about the scheme and also the consideration of other ‘more important’ factors for retention need to be taken into account.

(e) Summary

In this introductory chapter, we have examined the present situation for teacher recruitment and retention, in particular looking at recent literature published on these issues. We have seen in recent years that the balance in numbers between those entering and those leaving the profession has seen a steady improvement. However, some problem areas such as London see higher vacancy rates in their primary and secondary schools, compared to other areas. The review of literature on teacher recruitment highlighted that although teachers tend to go into the profession for intrinsic or altruistic reasons, people are deterred from the profession by more extrinsic reasons such as pay, workload, image and status of teaching, stress, long hours, excessive paperwork and student behaviour. The literature therefore suggested that these issues be tackled in order to improve teacher recruitment.

With respect to retention, workload, pupil behaviour, government initiatives, salary, stress, status/recognition and career prospects were highlighted in the literature as important issues to be tackled. School leadership was also highlighted as a key attitudes-influencing factor. Suggestions for tackling teacher retention therefore focused on these various reasons, e.g. reduce workload, improve pupil behaviour and better salary, as well as looking at management and communication issues within schools/colleges.

Within this context, financial incentives do appear to impact on teacher recruitment, and also possibly on teacher retention. However, in examining this impact, we also need to consider other issues such as how initiatives are promoted and the importance of other reasons affecting recruitment and retention.

2. Methodology for the Study

In this chapter, we highlight the evaluation methodology, in particular

• The evaluation questions to be answered by the study.

• How the sample of teachers was chosen for the evaluation.

• The actual breakdown of the chosen sample in terms teachers characteristics (e.g. gender and location of teachers).

• How the interviews with teachers were carried out.

(a) Introduction

Having provided some background on teacher recruitment and retention in the previous chapter, we now move on to describe the present evaluation of the Repayment of Teachers’ Loans Scheme. This evaluation was commissioned by the DfES in December 2003. Running from January to June 2004, the evaluation was designed to answer the following evaluation questions:

• To what extent were teachers’ decisions to enter teaching influenced by the prospect of having their loans written off?

• Where teachers had a choice of subjects that they could teach, did they choose a shortage subject to enable them to join the scheme?

• Is the prospect of having their loans written off likely to be an important factor in any future decisions on whether to stay in teaching?

The evaluation looked specifically at the pilot stage of the initiative, in particular seeking the views of teachers that had taken part in the first two years of the initiative (i.e. 2002/03 and 2003/04).

(b) Methodology

This evaluation set out to obtain both quantitative and qualitative data about the Repayment of Teachers’ Loans Scheme. Telephone interviews were chosen as the method for obtaining information from teachers, based on the fact that it would be easier for teachers to give extended responses to questions in interviews rather than in questionnaires. Cost and time implications dictated that these interviews would be carried out by telephone.

The evaluation was carried out in two parts. Firstly, a pilot study was carried out with a small number of teachers, in order to go through the sampling process and find out the response rate that we could expect from the evaluation. The pilot also provided an opportunity to try out the interview procedure and to analyse responses to questions to see whether we obtained the required information. Following the pilot, the main part of the evaluation was carried out with a larger sample of teachers.

(c) Sampling

This evaluation concentrated on teachers taking part in the pilot phase of the scheme, specifically those teaching English, Maths or Science. These included teachers working in Further Education institutions and also specialised teachers in primary schools. Teachers of other shortage subjects were not included in this study. A database of names and addresses of participating teachers in these subjects was provided by the Student Loans Company. After discounting teachers whose home addresses were not in the UK and removing names who appeared more than once in the database, this left an original population of 5,510 teachers to sample from.

For the pilot study, we were looking for 20 teachers to take part. Allowing for a response rate of 30% amongst the sample and for possible further attrition in numbers due to non-availability of interviewees, 100 teachers were selected at random and contacted by letter to take part in the study. 31 teachers subsequently agreed to take part in the pilot, and as this was more than was required for the pilot stage, 7 teachers were subsequently used for the main part of the study, leaving 24 teachers in the pilot study. Of these, 2 teachers could not be contacted during that period so interviews with 22 teachers were successfully completed. For the main part of the evaluation, we wanted at least 200 teachers to take part with the sample weighted so that 25% of the teachers would be from London. The problem of teacher shortages is more acute in the capital so this weighting ensured a larger number of teachers from there (the actual percentage of teachers from London in the original population was 11.4%). Based on the response and attrition rate from the pilot study, 800 letters were sent out to teachers with 200 of these being teachers from London. Subsequently 313 teachers agreed to take part (response rate of 39%) although 12 of these were discounted as the replies were received only after the main sample had been chosen. Together with the 7 teachers carried over from the pilot study, 308 teachers were therefore available for the main part of the evaluation. From these 308 teachers, 276 teachers were then selected to take part. This additional sampling was carried out because the response of teachers had been greater than expected and a reduction in numbers was required so that interviews could be carried out within the allocated time.

Subsequently, of the 276 teachers selected, 26 teachers could not be contacted during that period and 4 teachers withdrew from the study. In total therefore, there was an attrition of 11% in numbers, resulting in 246 interviews being successfully completed. Table 2.1 and

2.2 below summarise the resulting sample and the population in terms of location of the teachers and their gender.

Table 2.1: Breakdown of teacher numbers in terms of location

Region Number of teachers

interviewed

% of teachers interviewed

% breakdown of original population (with weighting)

East Midlands 17 6.9 7.0 East of England 20 8.1 7.6 Inner London 16 6.5 7.5 North East 13 5.3 4.7 North West 31 12.6 12.7 Outer London 44 17.9 17.5 South East 28 11.4 12.1 South West 20 8.1 8.5 Wales 13 5.3 4.7 West Midlands 22 8.9 8.5 Yorkshire & the Humber 22 8.9 9.1 London 60 24.4 25.0 Outside London 186 75.6 75.0

Table 2.2: Breakdown of teacher numbers in terms of gender Gender Number of teachers

interviewed % of teachers interviewed % breakdown of original population Female 170 69.1 68.5 Male 76 30.9 31.4

As we can see, the sample was representative of the original population in terms of the location of teachers and gender.

In addition to the two characteristics of teachers, we also had details of the type of schools in teachers worked (e.g. primary, secondary etc.), when teachers joined the scheme, what subjects they taught and their full- or part-time status. Table 2.3 shows the breakdown we obtained for the sample in terms of the percentages of teachers in the different phases of education.

Table 2.3: Breakdown of teacher numbers in terms of primary, secondary and further education6

Type of Establishment Number of teachers interviewed % of teachers interviewed

Primary 4 1.6 Middle 6 2.4 Secondary 224 91.1 Special 2 0.8 Further Education 10 4.1

6 This data was not available in the same detail for the original population. It was only after the sample was

Table 2.4 below gives a breakdown for the sample and the population in terms of when the teachers joined the scheme.

Table 2.4: Breakdown of teacher numbers in terms of when they joined the Repayment of Teachers’ Loans Scheme

When joined scheme Number of teachers interviewed % of teachers interviewed % breakdown of original population Sep 2002 – June 2003 149 60.6 63.0 July 2003 – Nov 2003 97 39.4 37.0 As stated previously, the evaluation specifically interviewed teachers of English, Maths and

Science only; teachers of other shortage subject (e.g. Modern Foreign Languages) were not included in the original population. A breakdown of teacher numbers, both for the sample and the population, is given in terms of subjects taught in the table below:

Table 2.5: Breakdown of teacher numbers in terms of subject

Subject Number of teachers

interviewed % of teachers interviewed % breakdown of original population English 88 35.8 38.4 Maths 42 17.1 21.4 Science 99 39.8 34.2 Combination of above 8 3.2 4.6 Further Education 10 4.1 1.4

The population and the sample also included full-time and part-time teachers (Table 2.6).

Table 2.6: Breakdown of teacher numbers in terms of full-time/part-time status

Full/Part-time Number of teachers interviewed % of teachers interviewed % breakdown of original population

Full-time 238 96.7 97.8

Part-time 8 3.3 2.2

Finally, when teachers were surveyed, over half of the respondents stated that they had changed careers before coming into teaching. These figures are detailed in Figure 2.7 below.

Table 2.7: Breakdown of numbers in terms of career changers and non-career changers Career change? Number of teachers % of teachers

No 111 45.1

Yes 134 54.5

(d) Interviewing Teachers

Having chosen the teachers to take part in the main part of the evaluation, the 276 selected teachers were allocated to 5 interviewers. The interviewers contacted the teachers during their stated convenient times, making allowances for needing to ring back if the teachers were unavailable. The interviews were carried out between the 15th March and 23rd April 2004.

The interviewers were asked to follow a script whilst carrying out the interviews with teachers. This ensured that the required information was provided to the teachers at the start and the end of the interview and that the interview questions were asked in a consistent way by the different interviewers. Following an introduction by the interviewer, where it was checked that the interviewee was aware that the call was being recorded (this was stated in the original letters to the teachers), the interview consisted of four separate parts:

(a) Questions looking at the teacher’s decision to enter teaching

(b) Questions looking at the teacher’s decision to teach a shortage subject (c) Questions looking at the teacher’s decision to remain in teaching (d) General views on the Repayment of Teachers’ Loans Scheme

A copy of the interview script used in the study is given in Appendix B of this report. In the following four chapters of the report, we highlight separately the findings from each of the above sections of the interviews.

3. Findings on Teacher Recruitment

In this chapter, we highlight the evaluation’s findings concerning teacher recruitment. The key findings of the chapter are

• Teachers’ reasons for entering teaching were largely altruistic or intrinsic in nature. This is in line with other studies examined previously. Teachers’ past perspectives and experience of teaching were also found to be important factors.

• In terms of reasons that might dissuade people from entering teaching, teachers most frequently cited pupil behaviour and workload/marking. The next most common reasons were the financial considerations of salary and cost of training.

• The Repayment of Teachers’ Loans Scheme had limited impact on teacher recruitment for this sample, due to the fact that the teachers were largely unaware of the scheme before they entered the profession. We estimated that around 10% of teachers had been influenced by the scheme to go into the profession.

• Conversely though, when teachers were asked whether the scheme was generally a good idea for recruiting teachers, only a small number disagreed that this might be the case, suggesting that the scheme does have the potential to attract teachers into the profession.

• Consideration therefore needs to be given to the way the scheme is advertised and promoted to ensure that it reaches key audiences.

(a) Introduction

Within the section on teacher recruitment, the interviews carried out as part of the evaluation broadly examined three areas concerning recruitment. Firstly, some of the questions looked at background issues relevant to the recruitment process. Secondly, general reasons for wanting to and not wanting to enter teaching were examined. Finally, specific views on the Repayment of Teachers’ Loans Scheme were gained from teachers. In order to make sense of the large amount of data gained from the interviews, we examine each of these areas separately. In referring to the results of the interviews, we will refer to Appendix C where the results from all the different interview questions are summarised (tables in this appendix referred to as Table C.1, Table C.2 etc.).

(b) Background to Recruitment Issues

When asked when they found out about the Repayment of Teachers’ Loans Scheme (Table C.10), most of the teachers in the sample (68.3%) stated that it was during their teacher training that they found out about it. Only 11.8% of the teachers stated that they had found out about the scheme before going into teaching. In general, people stated that they found out about the scheme through other people or teachers (32.9%), more officially from their lecturers (19.1%) or simply at some point during their course (18.7%) (Table C.9). Only a