Effects of the Balanced Satisfaction of

the Need for Autonomy, Relatedness,

and Competence Across Education

and Family on Well-Being in

Students

Faculty of Behavioural Management and Social Sciences

Study program: Psychology B. Sc.

Department: PPT

Alisa Kloppenborg

Bachelor´s Thesis

June 25, 2019

1

stSupervisor: Noortje Kloos

1

Abstract

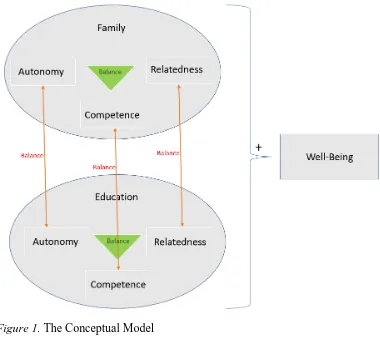

Background and Objectives. The current study is based on the Self-Determination Theory and the balance hypothesis. The Self-Determination Theory says that the three basic psychological needs autonomy, relatedness, and competence have to be satisfied to attain a good well-being. The balance hypothesis says that these three basic needs do not only have to be satisfied to achieve a good well-being, but they need to be balanced. Following this, the current study has the purpose of investigating whether a balanced need satisfaction of autonomy, relatedness, and competence positively relates to student´s well-being. This idea is taken further by deliberating whether a balance between contexts, in this case family and education, may also positively relate to student´s well-being.

Research Design and Methods. In this cross-sectional study, 76 students (Mage = 21.47 years)

took part by filling out an online survey. Through this study, relationships of the balance between autonomy, relatedness, and competence in both family and education on well-being were tested, and the relationship between these psychological needs across the contexts family and education on well-being. By calculating and summing absolute difference scores, balance scores of need satisfaction for both between the three needs and between the two contexts were created.

Results. The three needs in both contexts were positively related to well-being. However, none of the balance scores showed significant positive relations to well-being. Considering the hypotheses, relations of these balance scores to well-being were then tested by three hierarchical multiple regressions in total. All regression analysis showed non-significant effects. Thus, both hypotheses were not supported. Still, some correlations, (i.e., between most psychological needs separately and well-being) were found.

Discussion. The results did not show a relationship of the balance between the basic needs in education and family separately to well-being and no relationship of the balance between the needs across the two contexts to well-being. This may be explained by the current study´s focus on two contexts that were standardized for all participants without looking at individual differences on important life domains, or by differences in correlations between the psychological needs and well-being in both family and education.

2

Effects of the Balanced Satisfaction of the Need for Autonomy, Relatedness,

and Competence Across Education and Family on Well-Being in Students

Well-being is an important aspect of life. Especially in the ages between adolescence and adulthood, achieving and maintaining a good well-being is of high importance because of a high vulnerability to stress and mental illness in this period (e.g., Schulenberg, Sameroff, & Cicchetti, 2004). That is, for example, the case for students, on which this research will focus. Especially students are at risk for developing a lower well-being, which is highly due to the distress that they are confronted with, for instance, through their education (Adlaf, Gliksman, Demers & Newton-Taylor, 2001). When a good well-being is achieved, this may have further positive effects, such as on an individual´s educational performance (Edgar, Geare, Halhjem, Reese & Thoresen, 2015). Consequently, research focusing on students´ psychological health in terms of their education, and on reasons and theories that may predict their general well-being is needed. While there are many different definitions of well-well-being, in this paper, it is referred to as the hedonistic tradition of subjective well-being, i.e., happiness in terms of the absence of any negative affect and presence of positive affect on the affective component, and satisfaction with the overall life at the cognitive-evaluative component (Diener, 2000).

Based on earlier research about how well-being and the satisfaction with life might be achieved through fulfilling specific fundamental needs, Deci and Ryan (2000) entitled their associated theory as the Self-Determination Theory (SDT). This theory states that there are three fundamental psychological needs – namely, autonomy, relatedness, and competence – that have to be satisfied to achieve psychological health (Deci & Ryan, 2000). Autonomy refers to the need to own and control one´s behavior and to be able to act independently, which is satisfied when an individual can voluntarily introduce, execute, and control one´s own behavior.

3

the case, as found by a study on eight different cultures by Church and his colleagues (2012). The happiest individuals are found to be those that strive and succeed to satisfy all the three needs.

Following the Self-Determination Theory, research on this relation between basic psychological needs and well-being has been extended by the balance hypothesis, which was first introduced by Seldon and Niemiec (2006). This hypothesis argues that not only satisfying each of these needs separately is essential but also maintaining a balance between these needs. That means that it is not the sum of the satisfaction of the three basic needs that counts alone, but also the within-person balance of the satisfaction of these needs (Sheldon & Niemiec, 2006). Consequently, this balanced need satisfaction positively affects well-being. This was confirmed by other research, such as through a study on Nigerian and Indian students (Sheldon, Abad & Omoile, 2009). As Sheldon and Niemiec (2006) found, this balance between the needs is essential for everyone, no matter if a person scores high or low on the overall satisfaction scale. Thus, even if a person has a low sum score but a balance between the single scores on each need, this person has a higher well-being than someone with a high sum score but an imbalance between single scores. That is why this hypothesis argues that the focus should not be put on the three individual needs, but on the overall balance of these.

Research on these effects of a balanced need satisfaction on well-being was further expanded by Church et al. (2012), representing the same effects of the balance hypothesis in college students through multiple cultures – Australia, China, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, the Philippines, the United States, and Venezuela –, showing that this balance hypothesis holds true on a universal level. Recent research confirms this hypothesis in different studies and contexts, indicating that this hypothesis can be applied to different settings, such as to nursing homes (Kloos, Trompetter, Bohlmeijer, Westerhof, 2018) or volleyball players (Mack, Wilson, Oster, Kowalski, Crocker & Sylvester, 2011).

Moreover, in connection with the Self-Determination theory, another kind of balance was found to affect well-being. This other necessary type of balance is the balance across

4

Indeed, the original theory does not take into account different contexts and, until now, existing research on the Self-Determination Theory that considers specific contexts, has often been conducted in single contexts separately, such as sports (e.g., Wallhead, Hagger & Smith, 2010; Wilson, Mack, & Grattan, 2008), health care (e.g., Williams, Minicucci, Kouides, Levesque, Chirkov, Ryan & Deci, 2002; Kloos, Trompetter, Bohlmeijer, Westerhof, 2018), workplace (e.g., Chan & Hagger, 2012; Gómez-Baya & Lucia-Casademunt, 2018), and education (e.g., Guay, Ratelle, & Chanal, 2008; Hagger, Sultan, Hardcastle & Chatzisarantis, 2015). Then, the higher the satisfaction of the basic psychological needs in a specific context is, the higher is the healthy adaption and development in this context (Deci & Ryan, 2000). Still, there are some contexts, e.g., family, for which only little research is existing.

However, research that focused on more than one life domain similarly has given some significant insights. Results on a study of adolescents showed that not only high levels of need satisfaction in total in different contexts, e.g., friends, school, and home, are essential, but also the balance across these various contexts play a crucial role, which may characterize adolescents´ lives (Milyavskaya, Gingras, Mageau, Koestner, Gagnon, Fang & Boiché, 2009; Milyavskaya & Koestner, 2011). Thus, the original idea of the Self-Determination Theory has been expanded by saying that not only the psychological needs in general but also a balance across different life domains predicts a higher well-being than if there is an imbalance between these contexts, independent of how high the total satisfaction of the needs in each context is. Still, only a few studies about the balance across contexts focus on students specifically.

The Current Study

5

Is the balance between the three basic psychological needs autonomy, relatedness, and competence across the life domains education and family related to well-being, independently of the amount of need satisfaction?

Taking the discussed literature and knowledge into account, two hypotheses can be concluded. The first hypothesis is formulated to replicate the balance hypothesis of Sheldon and Niemiec (2006) specifically in family and education:

H1: There is a positive relationship between the balance of the three psychological needs and well-being in both education and family.

The second hypothesis focuses on both types of balances (between needs and across contexts):

H2: There is a positive relationship between the balance between each of the psychological needs autonomy, relatedness, and competence across the life domains education and family and well-being.

6 Figure 1. The Conceptual Model

Methods

Design

The current study had a quantitative, cross-sectional design in the form of an online survey. The questionnaire consisted of only one condition, i.e., every participant was supposed to answer the same questions. The methodology of the study was approved by the BMS ethics committee of the University of Twente (request-no. 190263). Additionally, this research was part of a bigger study in collaboration with another researcher.

Participants

7

from Taiwan and one from South Africa. Lastly, answers on the living arrangements of the participants showed that 19.7% lived alone, 15.8% at home with their family, and 64.5% together with roommates, friends, or partners.

Procedure

The sampling method was convenience sampling because participants were approached and requested to take part directly. Participants were obtained by sending the link to a questionnaire to students and requesting them to fill out that questionnaire. For developing the questionnaire and acquiring a link to that questionnaire, the online program “Qualtrics” was used, which was provided by the University of Twente. The survey started with the welcoming and the informed consent (see Appendix C). This gave information to the participants about the study, anonymity, the possibility to withdraw at any time, and whom to refer to or email with any questions. After reading the informed consent, participants could click on the further-button, which was an arrow at the end of the page, if they agreed to the informed consent and wanted to go on with the questionnaire. Then, the questionnaire followed with 95 items and one extra optional item, which asked the subjects to add any questions or remarks that they have left. After answering all items and the demographic questions, participants were thanked again for their participation, and the end of the procedure was reached. Participation took approximately 15 minutes.

Materials

To test the hypotheses, multiple scales were used testing well-being, need satisfaction in the domains family and education, and demographic information. Also, the domain “friends” was included in the questionnaire by the collaborating researcher, which will not be discussed in this research because it is not relevant here. To view the questionnaire and adjustments, see Appendix B.

8

2008). The Cronbach´s Alpha of the SWLS in the current sample was α = 0.73, meaning that the reliability of the scale was good.

Further, the Positive Affect Negative Affect Scale (PANAS) was used to measure the affective component of well-being. This scale contained 20 items asking the participants to indicate to what extent they had certain feelings over a specific time frame, e.g., “alert”, “strong” (Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, 1988). In this case, the time frame was specified to the past month. From the 20 total items, ten items concerned positive affect, e.g., “proud”, and ten items concerned negative affect, e.g., “afraid”. Answers ranged from 1 (= very slightly or not at all) to 5 (= extremely). Previous tests on the psychometric properties showed high reliability, for example, test-retest reliability, and validity on various measures of the PANAS (e.g., Watson et al., 1988; Crawford & Henry, 2004). In the current sample, the reliability of the scale was good, with a Cronbach´s Alpha of α = 0.81.

In order to receive one overall score for subjective well-being from the two separate scales, the scores of the items of positive affect from the PANAS and the scores on the SWLS items were added, and the scores of the items of negative affect from the PANAS were subtracted, based on the strategy of Sheldon and Niemiec (2006). The resulting scale score had a possible range between 7 and 35, with higher scores indicating higher well-being.

9

of these subscales were good. For education, it was α = 0.62 for autonomy, α = 0.70 for relatedness, and α = 0.68 for competence, meaning that the reliabilities of these subscales were acceptable.

Data Analysis

The data of all participants that were taken into consideration for the data analysis and the results were respondents that were students and filled out every item. From the original number of 93 participants, the data of 17 participants could not be included because they did not fit these inclusion criteria, i.e., were non-students (n = 3) or did not fill out the questionnaire until the end (n = 14). To analyze the data, IBM SPSS Version 24 was used. Since there was a missing value for one participant in the subscale of relatedness in the family context, the subscale score of this participant was computed by using the remaining seven items of that subscale. For the descriptive statistics, a correlation of r ≤ ±0.30 was considered weak, a correlation of r ≤ ±0.60 was considered as being moderate, and a correlation of r ≥ ±0.70 was considered strong (Akoglu, 2018). An alpha level below 0.05 was assumed as being significant.

Considering the first hypothesis, which was about the expectation of a positive relation to a balance between the three psychological needs and well-being in education and family, a balance of the need satisfaction in both education and family was calculated. This was done by computing three absolute difference scores between all possible pairs of the subscales (i.e., autonomy-relatedness, relatedness-competence, and competence-autonomy). After that, these three difference scores were summed up to one balance score, in accordance with the method of Sheldon and Niemiec (2006). Given the 7-point Likert-scale, 0 indicated a complete imbalance and 12 indicated a complete balance, after transforming the balance scores by subtracting them from the maximum possible score of 12. Once having computed the balance score for each participant, two hierarchical multiple regression analyses were conducted for each context with two steps. Here, well-being was the dependent variable. As a first step, the satisfaction of each of the three needs for the first context, which is family, was taken as the independent variable. As the second step, the balance scores of these needs within the context were added. This procedure was repeated for the second context of education.

10

in education and family, i.e., the absolute difference scores of autonomy in both contexts, relatedness in both contexts, and competence in both contexts. Given the 7-point Likert-scale, 0 indicated a complete imbalance, and 6 indicated a total balance, after subtracting the balance scores from 6. An overall balance score was calculated by computing three absolute difference scores of all possible pairs between the contexts of each psychological need, namely, the difference score of autonomy, the difference score of relatedness, and the difference score of competence. Then, the three absolute difference scores were added to one overall balance score and were subtracted by 12. This score had a possible range from 0, indicating a complete imbalance, to 12, indicating a complete balance. As the next step, relations to well-being were tested by conducting one multiple regression analysis, hierarchically done in three steps. Here again, well-being was the dependent variable. As the first step, all six separate satisfaction scores (i.e., autonomy, relatedness, and competence in the context of family, and autonomy, relatedness, and competence in the context of education) were taken as the independent variables. Second, the three difference scores of the two contexts for each psychological need were added as additional independent variables, which were three scores in total. As the last step, the balance score of the three difference scores was added as one independent variable.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

11

Table 1. Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlations of the Need Satisfaction and Balance Scores

Scale M SD 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Family

1.Autonomy 1-7 5.01 0.90 - 2.Relatedness 1-7 5.64 0.85 0.65** -

3.Competence 1-7 5.24 1.13 0.67** 0.67** -

4.Family 0-12 9.84 1.22 0.41** -0.12 -0.36** - Education

5.Autonomy 1-7 3.89 0.78 -0.05 -0.16 -0.11 0.09 -

6.Relatedness 1-7 4.81 0.72 0.05 0.06 -0.08 -0.08 0.52** -

7.Competence 1-7 4.79 0.84 0.20 0.10 0.16 0.05 0.48** 0.42** -

8.Education 0-12 9.28 1.26 -0.08 -0.20 -0.06 0.17 0.53** -0.21 -0.13 - Balances

9.Autonomy 0-6 4.60 0.88 -0.42** -0.19 -0.32** -0.28* 0.64** -0.44** 0.29* 0.32** -

10.Relatedness 0-6 4.91 0.81 -0.16 -0.36** -0.22 0.18 0.45** 0.62** 0.35** -0.03 0.53** -

11.Competence 0-6 4.90 0.82 -0.11 -0.02 -0.01 0.10 0.17 0.19 0.24* 0.01 0.26* 0.25* -

12.Overall 0-12 9.67 1.29 -0.11 -0.02 0.12 0.20 0.17 0.19 -0.04 0.23 0.37** 0.27* 0.34** -

Well-Being 7-35 33.43 13.42 0.30** 0.20 0.29* 0.18 0.35** 0.35** 0.46** -0.05 0.17 0.35** 0.09 0.05 -

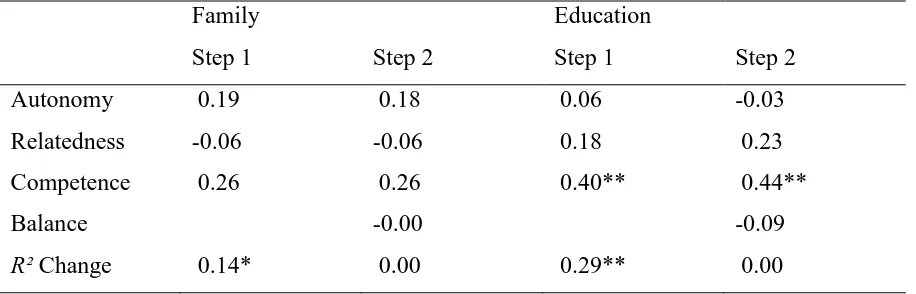

12 Testing Hypothesis 1

First, it was hypothesized that for both education and family, a balanced need satisfaction of autonomy, relatedness, and competence positively relates to well-being independent of the amount of need satisfaction. A hierarchical multiple regression was made for each context with well-being as the dependent variable.

Family. As the table below shows (Table 2), all three predictors of the model in the first and the second step of the analysis were not significant. So, these predictors did not explain unique variance of well-being. Thus, this also means that the balance score of family did not have a significant relationship to the dependent variable of well-being (for numbers, see Table 2). Further, the explained variance of the first step of the analysis of 14% showed significance, but the R² change score in the second step was not significant. This means that the regression analysis did not show significance of the balance score predicting well-being beyond autonomy, relatedness, and competence.

13

Table 2. Beta´s and Additional Explained Variance of the Hierarchical Multiple Regression Models (Hypothesis 1)

Family

Step 1 Step 2

Education

Step 1 Step 2

Autonomy 0.19 0.18 0.06 -0.03

Relatedness -0.06 -0.06 0.18 0.23

Competence 0.26 0.26 0.40** 0.44**

Balance -0.00 -0.09

R² Change 0.14* 0.00 0.29** 0.00

Note: *p < .05. **p < .01 (two-tailed).

Testing Hypothesis 2

14

Table 3. Beta´s and Additional Explained Variance of the Hierarchical Multiple Regression Models (Hypothesis 2)

Step 1 Step 2 Step 3

Autonomy Family 0.08 0.04 0.04

Relatedness Family -0.04 0.13 0.11 Competence Family 0.31* 0.27 0.31 Autonomy Education 0.13 0.16 0.15 Relatedness Education 0.20 0.04 0.05 Competence Education 0.31** 0.27* 0.23

Balance Autonomy 0.05 0.01

Balance Relatedness -0.29 -0.29

Balance Competence -0.01 -0.03

Overall Balance 0.08

R² Change 0.40** 0.03 0.00

Note: *p < .05. **p < .01 (two-tailed).

Discussion

The aim of the research was testing whether a balance between the three basic psychological needs autonomy, relatedness, and competence in both family and education positively relate to well-being and whether there is a positive relation of the balance among each of these psychological needs across family and education to well-being. In this study, no relationships were found between the balances of the psychological needs and well-being in either of the contexts on well-being. Further, no relationships were found between the balance among each of the psychological needs across the two contexts and well-being.

15

only report results with small effects (e.g., Mack, Wilson, Oster, Kowalski, Crocker & Sylvester, 2011). So, it may be the case that a general balance between the needs and contexts is essential for well-being, but a balance within the two specific contexts may not.

Another possible reason considers the correlations that were found in the results of the current study and the models that were tested. The current results show varying correlations of the three needs in both contexts to well-being, and not all psychological needs in the tested models seemed to predict well-being. This means, for the context of family, that autonomy and competence were found to be related to well-being, but relatedness was not. Thus, it may be the case that autonomy and competence are much more substantial in the context of family than relatedness. These findings may be explained by other research stressing the importance of autonomy or competence alone. Several studies focused on autonomy solely, for example, by researching autonomy support from educational institutions or family members, and the effects on well-being. Since autonomy support was found to influence well-being and the associated motivation of students positively, it may mean that autonomy needs to have a high satisfaction independent of the other two psychological needs (e.g., Williams & Deci, 1996; Black & Deci, 2000; Chirkov & Ryan, 2001; Joussemet, Landry & Koestner, 2008). Future research is needed to test the importance of competence alone and the effects on well-being in the family context. In the context of education, competence had a higher relation to well-being than autonomy and relatedness did and was the only need that uniquely related to well-being in the regression analysis. Therefore, it may be the case that competence in education has a higher value for students than autonomy and relatedness. In line with these results, a study of Tian, Chen, and Huebner (2014) showed that in education, especially competence is of high importance for student´s well-being and should be a key aim. Especially in terms of student´s educational motivation, competence was found to be a crucial need compared to autonomy and relatedness (e.g., Faye & Sharpe, 2008). On the other hand, other research, which is also in line with the current results, suggest that autonomy may not be as crucial for student´s well-being in their educational context and relatedness may only be necessary for student´s satisfaction with teachers but not with their educational courses generally (Filak & Sheldon, 2003; León & Núñez, 2013).

16

this may add up to a similar relevance for all psychological needs, leaving the balance in a student´s overall life with much higher importance. More specifically, if each need is the most important one in some life domain, each of these needs may be as important as the others in an overall picture of a student´s life. Still, more research is needed here to find out about the balance between the needs in specific contexts and requirements for the effects of this balance on well-being.

Considering the second hypothesis, not finding support for the balance between contexts was not in line with existing research that did support this theory (e.g., Milyavskaya et al., 2009; Milyavskaya & Koestner, 2011). Similar to the first hypothesis, a reason for this may be the differences in correlations of each psychological need in context to well-being. Correlations between the psychological needs and well-being vary across the contexts. Consequently, a balance between these contexts may not be necessary as long as the satisfaction is high for each need in those contexts, in which their satisfaction mostly predicts well-being, (e.g., satisfaction of competence mostly predicts well-being in education). Looking at the correlations that were found in existing studies on other contexts, these variations of the importance of the psychological needs for well-being are also visible, such as in cases of sports (Podlog, Lochbaum & Stevens, 2010) or work (Gomez-Baya & Lucia-Casademunt, 2018). An overall balance across family and education for all needs, then, may not be as important as having a high need satisfaction for those needs that most predict well-being in one specific context. This would be comparable to the mentioned possible explanations for not finding support for the first hypothesis.

Additionally, it may be the case that the participants in this study did not personally consider the two used contexts family and education as the most important ones. In other words, it may be that for these students, other life domains than family and education may be more important in their lives and that a balance between these other important life domains may actually have effects on the student´s well-being, e.g., sports and music. Overall, it is indeed possible that the current two contexts are two of the most important contexts for students, but it still varies for each individual separately (Blais et al., 1990).

17

similar research is needed with another sample, that is more representative. Still, the current findings are useful when looking at need satisfaction in German women.

Secondly, there was a noteworthy final remark of a participant that was indicated in the optional space at the end of the questionnaire. The indication was that for the scale of need satisfaction in family, there was no explanation of whether only parents and siblings are meant by “family” or also more distant relatives, e.g., uncles or grandparents. Leaving this interpretation open for the participants may have altered the results in that the definition of family influences the participants´ answers. Thus, when replicating this study, a specific definition for family needs to be indicated at the beginning of the need satisfaction scale.

As the last limitation, this study was a cross-sectional one without testing longitudinal effects, which means that answers on this questionnaire are only indicated at a specific point in time without a follow-up questionnaire. Therefore, although this study was useful in that it tested the relationships of the concepts to well-being, there cannot be any conclusions drawn on the causation of these, i.e., whether need satisfaction affects well-being, because no direction of causation was tested and unknown third variables may cause or affect these relationships. Additionally, although the participants may have a good well-being without having a balanced need satisfaction, this may be due to short-term effects of heightened well-being after an increased satisfaction of only one psychological need (Sheldon & Niemiec, 2006). After having had a balanced need satisfaction, students may achieve higher well-being in the short-term, e.g., because of happiness about an increased competence at one point, but may make that student have a lowered well-being in the long run. To further test causality and long-term effects, future research is needed conducting a similar study in terms of a longitudinal study.

18

Next to the implications for future research that were already discussed above, another may be a combination of qualitative and quantitative research similar to the study conducted by Milyavskaya and Koestner (2011) but associated with the current findings and focused on students. The idea is that students are first individually asked to indicate all important personal life domains to later find out about students´ balanced need satisfaction in both within these personal life domains and across these. Such a semi-standardized study may give further insights into current results and discussions on whether individually relevant life domains may show other results for student´s well-being than standardized contexts such as family and education.

Conclusion

19

Appendix

Appendix A: References

Adlaf, E. M., Gliksman, L., Demers, A., & Newton-Taylor, B. (2001). The Prevalence of Elevated Psychological Distress Among Canadian Undergraduates: Findings from the 1998 Canadian Campus Survey. Journal of American College Health, 50(2), 67-72. doi:10.1080/07448480109596009

Akoglu, H. (2018). User´s Guide to Correlation Coefficients. Turkish Journal of Emergency Medicine, 18(3), 91-93. doi:10.1016/j.tjem.2018.08.001

Black, A. E., & Deci, E. L. (2000). The effects of instructors' autonomy support and students' autonomous motivation on learning organic chemistry: A self‐ determination theory perspective. Science Education, 84(6), 740–756. doi:10.1002/1098-237X(200011)84:6<740::AID-SCE4>3.0.CO;2-3

Blais, M. R., Vallerand, R. J., Brière, N. M., Gagnon, A., & Pelletier, L. G. (1990). Significance, structure, and gender differences in life domains of college students. Sex Roles, 22(3-4), 199-212. doi:10.1007/bf00288192

Chan, D. K. C., & Hagger, M. S. (2012). Autonomous forms of motivation underpinning injury prevention and rehabilitation among police officers: An application of the trans-contextual model. Motivation and Emotion, 36(3), 349-364. doi:10.1007/s11031-011-9247-4

Chirkov, V. I., & Ryan, R. M. (2001). Parent and teacher autonomy-support in Russian and U.S. adolescents: Common effects on well-being and academic motivation. Journal of Cross Cultural Psychology, 32(5), 618–635. doi:10.1177/0022022101032005006

Church, A. T., Katigbak, M. S., Locke, K. D., Zhang, H., Shen, J., & de Jesús Vargas-Flores, J., … Ching, C. M. (2012). Need Satisfaction and Well-Being: Testing Self-Determination Theory in Eight Cultures. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 44(4), 507-534. doi:10.1177/0022022112466590

Crawford, J. R., & Henry, J. D. (2004). The Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS): Construct validity, measurement properties and normative data in a large non-clinical sample. British Journal Of Clinical Psychology, 43(3), 245-265. doi:10.1348/0144665031752934

20

Deci, E. L., Ryan, R. M., Gagné, M., Leone, D. R., Usunov, J., & Kornazheva, B. P. (2001). Need satisfaction, motivation, and well-being in the work organizations of a former eastern bloc country: A cross-cultural study of self-determination. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 27(8), 930-942. doi:10.1177/0146167201278002

Diener, E. (2000). Subjective well-being: The science of happiness and a proposal for a national index. American Psychologist, 55(1), 34-43. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.34 Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The Satisfaction With Life

Scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(1), 71-75. doi:10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13

Edgar, F., Geare, A., Halhjem, M., Reese, K., & Thoresen, C. (2015). Well-being and performance: measurement issues for HRM research. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 26(15), 1983-1994. doi:10.1080/09585192.2015.1041760

Faye, C., & Sharpe, D. (2008). Academic motivation in university: The role of basic psychological needs and identity formation. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science/Revue canadienne des sciences du comportement, 40(4), 189-199. doi:10.1037/a0012858

Filak, V. F., & Sheldon, K. M. (2003). Student Psychological Need Satisfaction and College Teacher-Course Evaluations. Educational Psychology, 23(3), 235-247. doi:10.1080/0144341032000060084

Gómez-Baya, D., & Lucia-Casademunt, A. M. (2018). A self-determination theory approach to health and well-being in the workplace: Results from the sixth European working conditions survey in Spain. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 48(5), 269-283. doi:10.1111/jasp.12511

Gómez-Baya, D., Lucia-Casademunt, A. M., & Salinas-Pérez, J. A. (2018). Gender differences in psychological well-being and health problems among European health professionals: Analysis of psychological basic needs and job satisfaction.

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(7). doi:10.3390/ijerph15071474

Guay, F., Ratelle, C., F. & Chanal, J. (2008). Optimal learning in optimal contexts: The role of self-determination in education. Canadian Psychology, 49(3), 233-240. doi:10.1037/a0012758

21

educational and out-of-school contexts is related to mathematics homework behavior and attainment. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 41, 111-123. doi:10.1016/j.cedpsych.2014.12.002

Joussemet, M., Landry, R., & Koestner, R. (2008). A self-determination theory perspective on parenting. Canadian Psychology,49(3), 194-200. doi:10.1037/a0012754

Kloos, N., Trompetter, H. R., Bohlmeijer, E. T., & Westerhof, G. J. (2018). Longitudinal Associations of Autonomy, Relatedness, and Competence with the Well-being of Nursing Home Residents. The Gerontologist, 0, 1-9. doi:10.1093/geront/gny005 León, J. & Núñez, J. L. (2013). Causal Ordering of Basic Psychological Needs and Well-Being.

Social Indicators Research, 114(2), 243-253. doi:10.1007/s11205-012-0143-4

Mack, D. E., Wilson, P. M., Oster, K. G., Kowalski, K. C., Crocker, P. R. E., & Sylvester, B. D. (2011). Well-being in volleyball players: Examining the contributions of independent and balanced psychological need satisfaction. Psychology of Sport & Exercise,12(5), 533-539. doi:10.1016/j.psychsport.2011.05.006

Milyavskaya, M., Gingras, I., Mageau, G. A., Koestner, R., Gagnon, H., Fang, J., & Boiché, J. (2009). Balance Across Contexts: Importance of Balanced Need Satisfaction Across Various Life Domains. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 35(8), 1031-1045. doi:10.1177/0146167209337036

Milyavskaya, M., & Koestner, R. (2011). Psychological needs, motivation, and well-being: A test of self-determination theory across multiple domains. Personality and Individual Differences, 50(3), 387-391. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2010.10.029

Pavot, W., & Diener, E. (2008). The Satisfaction With Life Scale and the emerging construct of life satisfaction. Journal of Positive Psychology, 3(2), 137–152. doi:10.1080/17439760701756946

Podlog, L., Lochbaum, M., & Stevens, T. (2010). Need satisfaction, well-being, and perceived return-to-sport outcomes among injured athletes. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology,22(2), 167-182. doi:10.1080/10413201003664665

Reis, H. T., Sheldon, K. M., Gable, S. L., Roscoe, J., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). Daily Well-Being: The Role of Autonomy, Competence, and Relatedness. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 26(4), 419-435. doi:10.1177/0146167200266002

22

Sheldon, K. M., Abad, N., & Omoile, J. (2009). Testing Self-Determination Theory via Nigerian and Indian adolescents. International Journal of Behavioral Development,

33(5), 451-459. doi:10.1177/0165025409340095

Sheldon, K. M., & Niemiec, C. P. (2006). It's not just the amount that counts: Balanced need satisfaction also affects well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,

91(2), 331-341. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.91.2.331

Tian, L., Chen, H., & Huebner, E. S. (2014). The longitudinal relationships between basic psychological needs satisfaction at school and school-related subjective well-being in adolescents. Social Indicators Research, 119(1), 353-372. doi:10.1007/s11205-013-0495-4

Tian, L., Tian, Q., & Huebner, E. S. (2016). School-related social support and adolescents’ school-related subjective well-being: The mediating role of basic psychological needs satisfaction at school. Social Indicators Research, 128(1), 105-129. doi:10.1007/s11205-015-1021-7

Vlachopoulos, S. P., Asci, F. H., Cid, L., Ersoz, G., González-Cutre, D., Moreno-Murcia, J. A., & Moutão, J. (2013). Cross-cultural invariance of the basic psychological needs in exercise scale and need satisfaction latent mean differences among Greek, Spanish, Portuguese and Turkish samples. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 14(5), 622-631. doi:10.1016/j.psychsport.2013.03.002

Wallhead, T. L., Hagger, M., & Smith, D. T. (2010). Sport education and extra-curricular sport participation: An examination using the trans-contextual model of motivation.

Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 81(4), 442-455. doi:10.1080/02701367.2010.10599705

Watson, D., Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(6), 1063–1070. doi:10.1037//0022-3514.54.6.1063

Williams, G. C., & Deci, E. L. (1996). Internalization of biopsychosocial values by medical

students: a test of self-determination theory. Journal of Personality and Social

Psychology, 70(4), 767–779. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.70.4.767

23

Wilson, P. M., Mack, D. E., & Grattan, K. P. (2008). Understanding motivation for exercise: A self-determination theory perspective. Canadian Psychology, 49(3), 250–256. doi:10.1037/a0012762

Appendix B: Questionnaire

Type Item Answers/Scale

SWLS In most ways my life is close to my ideal. The conditions of my life are excellent. I am satisfied with my life.

So far, I have gotten the important things I want in life. If I could live my life over, I would change almost nothing.

7-point Likert-scale (1 = strongly disagree; 7 = strongly agree) PANAS Interested

Distressed Excited Upset Strong Guilty Scared Hostile Enthusiastic Proud Irritable Alert Ashamed Inspired Nervous Determined Attentive Jittery Active Afraid 5-point Likert-scale (1 = very slightly or not at all; 5 = extremely) Basic Psychological Need Satisfaction Scale “Family”

I feel like I can make a lot of inputs to deciding how things get done in my family.

I really like my family.

I do not feel very competent when I am with my family. People in my family tell me I am good at what I do. I fell pressured by my family.

I get along with the people in my family.

I pretty much keep to myself when I am with my family. I am free to express my ideas and opinions in my family. I consider the people in my family to be my friends.

I have been able to learn interesting new skills from my family. When I am with my family, I have to do what I am told. (Most days I feel a sense of accomplishment with my family.) Most days I feel capable and effective with my family. My feelings are taken into consideration by my family.

With my family, I do not get much of a chance to show how capable I am. My family cares about me.

There are not many family members that I am close to. I feel like I can pretty much be myself with my family. The people in my family do not seem to like me much. When I am with my family, I often do not feel very capable.

24

There is not much opportunity for me to decide for myself how to go about something with my family.

People in my family are pretty friendly towards me.

Basic Psychological Need Satisfaction Scale “Friends” (not used in the current analysis)

I feel like I can make a lot of inputs to deciding how things get done with my friends.

I really like my friends

I do not feel very competent when I am with my friends. My friends tell me I am good at what I do.

I feel pressured by my friends. I get along with my friends.

I pretty much keep to myself when I am with my friends.

I am free to express my ideas and opinions when I am with my friends. I consider the people I regularly interact with to be my friends. I have been able to learn interesting new skills from my friends. When I am with my friends, I have to do what I am told. Most days I feel a sense of accomplishment with my friends. Most days I feel capable and effective with my friends.

With my friends, I do not get much of a chance to show how capable I am. My friends care about me.

There are not many friends that I am close to. I feel like I can pretty much be myself with my friends. My friends do not seem to like me much.

When I am with my friends, I often do not feel very capable.

There is not much opportunity for me to decide for myself how to go about something with my friends.

My friends are pretty friendly towards me.

7-point Likert-scale (1 = not at all; 7 = very true) Basic Psychological Need Satisfaction Scale “Education”

I feel like I can make a lot of inputs to deciding how my work gets done at my university.

I really like the people at my university.

I do not feel very competent when I am at my university. People at my university tell me I am good at what I do. I feel pressured at my university.

I get along with the people at my university.

I pretty much keep to myself when I am at my university. I am free to express my ideas and opinions at my university. I consider the people I work with at my university to be my friends. I have been able to learn interesting new skills at my university. When I am at my university, I have to do what I am told. (Most days I feel a sense of accomplishment from studying.) Most days I feel capable and effective when I am studying. My feelings are taken into consideration at my university.

At my university I do not get much of a chance to show how capable I am. People at my university care about me.

There are not many people at my university that I am close to. I feel like I can pretty much be myself at the university. The people at my university do not seem to like me much. When I am studying, I often do not feel very capable.

There is not much opportunity for me to decide for myself how to go about my work at my university.

People at the university are pretty friendly towards me.

7-point Likert-scale (1 = not at all; 7 = very true)

Demographics What is your nationality? German; Dutch; Other (text box)

25

What is your gender? Male; Female;

Other; Prefer not to answer

Are you currently enrolled at a university? If you are, for how many years have you been enrolled at that university?

Yes (text box); No

What is the name of the University that you are currently enrolled at? (optional)

(text box)

What degree do you expect to achieve from your current study program? Bachelor´s Degree; Master´s Degree; Staatsexamen; Other (text box)

Please indicate your current living arrangement. I live at home with

my family; I live on my own; I live with roommates, frineds or a partner in a shared flat

In case you have some final remarks (for example, if you did not understand a question), you can write them down in the text box below.

(text box)

You have reached the end of our questionnaire. Thank you again for participation.

If you have any questions regarding the questionnaire or our research, don't hesitate to contact us or our supervisor.

Furthermore, if you would like to learn about our study's result, you can write us an email as well.

Alisa Kloppenborg (a.kloppenborg@student.utwente.nl) Carina Kühne (c.kuhne@student.utwente.nl)

Noortje Kloos (supervisor) (n.kloos@utwente.nl)

Appendix C: Informed Consent

Dear participants,

Thank you for participating in our study! You are helping a lot with our graduation process! With this research we want to gather knowledge about how students perceive the choices that they have in life (autonomy), the connections they feel (relatedness), and how competent they feel (competence) in various areas of their life. Here, the contexts in life that are considered are family, education, and friends. Then, connections between this and well-being are tested.

26

confidential, and data will be used only in combination with the answers of all participants. The questionnaire will take approximately 15 minutes.

The participation is fully voluntary, which means that you can withdraw from the study any time without consequences. Withdrawing means that your answers will not and cannot be used for the research. There are no probable consequences of you taking part in this study. The data and results of the study will only be published and stored anonymously and confidentially to third parties. The data may also be used for other future research, but still anonymously. If you still have any questions left, you can either just ask us or write an email to a.kloppenborg@student.utwente.nl or c.kuhne@student.utwente.nl (or our supervisor n.kloos@utwente.nl).