Case Report

Composite angioimmunoblastic T cell/diffuse large

B-cell lymphoma treated with reduced-intensity

conditioning HLA-haploidentical allo-HSCT: a

case report and review of the literature

Ruimin Hong, Lixia Sheng, Guifang Ouyang

Department of Hematology, The Affiliated Ningbo Hospital of Zhejiang University, Ningbo 315000, Zhejiang, China

Received September 21, 2018; Accepted October 25, 2018; Epub November 1, 2018; Published November 15, 2018

Abstract: Cases of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) occurring together with angioimmunoblastic T cell lym-phoma (AITL) are rare. Treatments for AITL and DLBCL composite lymlym-phoma include chemotherapy, targeted thera-py, immunomodulatory therapy and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, but no standard treatment for this

ag-gressive disease has yet been defined. There are no case reports on AITL/DLBCL composite lymphoma treated with

allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HSCT). Herein, we report a case of AITL/DLBCL composite lymphoma treated with reduced-intensity conditioning HLA-haploidentical allo-HSCT, and the patient still remains in complete remission (CR) after a year of regular follow-up.

Keywords: Angioimmunoblastic T cell lymphoma, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, composite lymphoma, allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation

Introduction

Angioimmunoblastic T cell Lymphoma (AITL) is an aggressive type of peripheral T cell lym-phoma (PTCL), accounting for 18.5% of PTCL, and 1%-2% of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), respectively [1]. AITL is clinically characterized by lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, or associated with B symptoms (fever, weight loss, night sweats), and rash in up to 50% of patients. Other clinical manifestations include arthritis, arthralgia, hydrothorax, ascites, pneumonia, neuropathies, and gastrointestinal involvement [2]. AITL has a poor prognosis, with a relapse rate of 56%, a median survival of 36 months, and a 5-year survival of 36% [3]. AITL originates from the helper T cells of the lymphoid follicles. The pathological features of the lymph nodes of patients with AITL include small lymphocytes with cytological atypia clustered around high endothelial venules, and CXCL 13 as well as PD-1 are expressed in most malignant cells of these patients [4, 5]. AITL is commonly accom-panied by a proliferation of B cell and EBV infec-tions [6]. In rare cases, diffuse large B-cell

lym-phoma (DLBCL) occurs together with AITL. Treatments for AITL and DLBCL composite lym-phoma include chemotherapy, targeted thera-py, immunomodulatory therathera-py, and hemato-poietic stem cell transplantation, but no st- andard treatment for this aggressive disease have yet been defined [7]. Herein, we report a case of AITL/DLBCL composite lymphoma treated with reduced-intensity conditioning HLA -haploidentical allo-HSCT, and the patient still remains in complete remission (CR) after a year of regular follow-up.

Case presentation

platelet count of 77*10^9/L; a sedimentation rate of 84 mm/h; a lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) level of 318 U/L; an EBV-DNA copy of 3.43*10^4/ml; an ultrasound examination suggested generalized lymphadenopathy; a computed tomography (CT) revealed no en- larged lymph nodes in either the mediastinum

[image:2.612.93.524.70.167.2]or the abdominal cavity. A biopsy sample of the left neck lymph node showed the disappear-ance of the normal structure of a lymph node, as well as the unobvious lymphoid follicles and lymphatic sinuses, which were infiltrated by dysplastic moderated large cells with mitosis (Figure 1). An immunohistochemical analysis

Figure 1. Histopathological and morphological findings of the lymph node biopsy.

Figure 2. Immunohistochemical findings of the lymphoma node biopsy that were positive for CD2, CD3, CD4, CD8,

[image:2.612.90.523.209.591.2]determined that the small to medium-sized lymphoid cells were strongly positive for CD2, CD3, CD4, CD5, CD8, TIA-1; the large cells rep-resented immunoreactive for BCL-6, BCL-2, C-myc, MUM-1, CD20, CD79A, PAX-5, and were scattered EBER positive with a 80% rate of Ki-67; in addition, the proliferation of follicular dendritic cells expressing CD21 were remark-able in the node (Figure 2). According to the clinical presentation combined with the histo-logical results, we made a primary diagnosis of AITL composite with DLBCL.

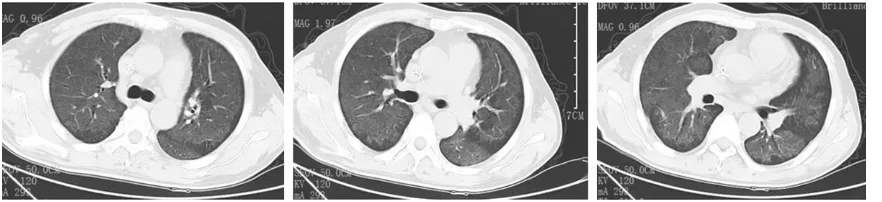

After that, the patient returned to a local hospi-tal for further treatment. In January 2016, he received CHOP-L (cyclophosphamide, doxorubi-cin, vincristine, prednisone, and pegaspargase) for one cycle. Unfortunately, he experienced a severe infection caused by myelosuppression. Then the second cycle of chemotherapy was modulated to half the CHOP regimen. However, he suffered from fever, cough and sputum, chest tightness and dyspnea 5 days later. His chest CT scan indicated a severe pneumonia caused by pneumocystis carinii infection (Fig- ure 3). For more specialized therapy, he imme-diately returned to our department. After treat-ment with caspofungin, sulfamethoxazole, and methylprednisolone, he recovered, since his symptoms of fever, cough, sputum, and chest

tightness disappeared, and his chest CT imag-es showed obviously alleviated pneumonia (Figure 4).

Meanwhile, we performed a further molecular pathologic examination of the patient’s lymph nodes and identified the clonal rearrangement of the IGH, IGK and TCRβ genes. Finally, the diagnosis of AITL composite with DLBCL was further confirmed. In order to design a precise treatment, we evaluated his condition again in May 2016. At that time, newly developed, enlarged lymph nodes in the mediastinal and hilar, retroperitoneum, and mesenteric spaces were displayed by CT scan. And a bone marrow biopsy and immunohistochemistry showed lym-phoma had infiltrated the bone marrow. All these findings indicated disease progression. Since the neoplastic cells were positive for CD20, we suggested that he follow the R-CHOP protocol. He refused because of the high expense of Rituximab. Eventually, the patient received CHOP + L (cyclophosphamide, doxoru-bicin, vincristine, prednisone, and pegasparga-se), CEOP + Lenalidomide (cyclophosphamide, etoposide, vindesine, methylprednisolone, le- nalidomide), Lenalidomide + ECHOP (lenalido-mide, cyclophospha(lenalido-mide, epirubicin, vincris-tine, dexamethasone, and vincristine), DICE (dexamethasone, ifosfamide, cisplatin and

[image:3.612.88.526.71.178.2]eto-Figure 3. Chest CT images with the diagnosis of severe pneumonia.

[image:3.612.89.530.216.317.2]Table 1. Summary of patients with AITL-developed secondary EBV-associated B cell lymphoma

Case No. Age/Sex Diagnosis Interval Biopsy site IgH TCR EBER Treatment Outcome Ref

1 66/F AITL LN – – – Withdraw Methotrexate Spontaneous remission [12]

DLBCL 9 m SK – – +

2 73/M DLBCL LN – – – CHOP*1 R-CHOP*5 Disease progressed [13]

AITL 6 m LN – – – GEM + L-ASP + Lobaplatin Died, 2 months

3 59/F AITL LN – + – CHOP*6/AUTO-HSCT CR [14]

DLBCL 5 m Adrenal gland – – – R CR

4 65/M AITL LN – – + CHOP*6 NR [15]

DLBCL 19 m SK – – + R-CHOP*1 PR

5 75/F AITL/DLBCL CLs Ascites/gallbladder + – – Five courses of chemo-therapy Died of cholecystitis [16]

– – +

6 65/F AITL LN – + +/– IHOP*9 + Radiotherapy CR [17]

DLBCL 26 m LN + – + R-CHOP PR

7 77/M AITL LN – + – ND Died of respiratory failure, 3 months [18]

DLBCL 8 m LN – – + ND

8 80/M AITL LN – + +/– Prednisone 50 mg qd [19]

DLBCL 4 m Cerebellum + – + R/R + MTX + VCR Died, 4 months

9 62~90 AITL/DLBCL CLs (23 cases) LN 66.7% 70.6% 72% 7 deaths [20]

10 36/F AITL LN ND ND ND FED + Auto-HSCT CR [21]

DLBCL 13 m LN ND ND ND R-CHOP + Allo-HSCT CR

11 55/M PITL LN – – – CHOP*8 CR [22]

AITL 12 m LN + + + ESHAP*2 + BEAM + Auto-HSCT CR

DLBCL 3 m LN + – – MTX + 6-MP + R*6 CR

12 69/F AITL LN – + – CHOP*7 CR [23]

DLBCL 56 m SK + – + Responded temporarily, Died, 53 months

13 48/F AITL/DLBCL CLs LN + – + CHOP*6 + ESHAP + Auto-HSCT CR [24]

14 66/F AITL LN – + – THPCOP + CHASE*2 Relapse, 19 months [25]

DLBCL 18 m Small intestine + – + / Died of respiratory failure, 2 months

15 59/M AITL LN – – – (FAC + Lemtrada)*2 + CHOP*2 CR [26]

DLBCL 11 m Stomach – – + / Died, 2 weeks

poside), ESHAP (etoposide, ifosfamide, mer-captopurine, and cytarabine) for a total of 5 courses successively, but he achieved a poor response. Given his resistance to chemothera-py and bone marrow involvement, it was unsuit-able to undertake auto-HSCT. Therefore, a reduced-intensity conditioning (RIC-mbucyflu-ATG) allo-HSCT was conducted in October 2016. The conditioning protocol consisted of cytarabine (8 g/m2 for two days), busulfan (9.6

mg/kg for three days), cyclophosphamide (2.0 g/m2 for two days), fludarabine (150 mg/m2 for

five days), MECCNU (2.0 g/m2 for one day),

anti-thymocyte globulin (10 mg/kg for four days). After that, we transfused bone morrow stem cells from his sibling brother to him, containing a total of 3.17*108/kg MNCs and 5.8×106/kg

CD34+ cells. In addition, peripheral blood stem cells mobilized by G-CSF were also infused into his body, including MNCs of 8.14×108/kg and

CD34+ cells of 5.8×106/kg. The following day,

he received third party umbilical cord blood with 0.88×108 of MNC and 38.08×105 of

CD34+ cells. Meanwhile, short-term methotrex-ate with cyclosporine and mycophenolmethotrex-ate mofetil were carried out to prevent graft versus host disease (GVHD). Thereafter, the implanta-tion of the granulocytic and platelets took place in +15 d and +17 d after transplantation, respectively. In March 2017, we reassessed his condition using bone marrow biopsy and immu-nochemistry. The results indicated his propor-tion of B cells, T cells and plasma cells were about normal, and his expression of EBER was negative. Promisingly, the patient remains in CR a year of regular follow-up.

Discussion

Composite lymphomas (CLs) are defined as two or more different morphological types of malig-nant lymphomas rising in the same issue or organ, and account for 1-4.7% of all lymphomas [8]. CLs containing both T- and B-cell compo-nents (CTBLs) is especially rare. AITL/DLBCL composite lymphoma needs to be differentiat-ed from AILT complicatdifferentiat-ed by polyclonal B cell proliferation, T- and B-cells of the former are all tumorous, while B-cells of the latter are reac-tive hyperplasias. So the diagnosis of CTBLs depends on morphology, immunohistochemis-try, and molecular biology techniques. Now- adays, the pathogenesis of AITL/DLBCL com-posite lymphoma remains uncertain, but here are several hypotheses [9]: CLs were

trans-formed from pluripotent hematopoietic stem cells which have the potential to differentiate into T- and B-cell lymphoma; simultaneous evo-lution of both B- and T-cell leads to CLs; lym-phoma-associated immune dysfunction also plays a pivotal role which is closely related to EBV infection. Since EBV preferentially infects B cells and can transform quiescent B cells into permanent cells, otherwise EBV can also infect other lymphoblastoid cells [10]. In a hypotheti-cal model proposed by Dunleavy et al. [11], through MHC class II molecules, EBV-infected B cells provide stimulatory signals for helper T cell activation and CXCL 13 production by pre-senting EBV antigen proteins (EBNA-1) and latent membrane protein (LMP-1) to them. These proteins can up-regulate the expression of CD28 ligands. In turn, CXCL 13 might moti-vate further B cell activation, creating a co-stimulatory loop. This complex interaction be- tween EBV-infected B cells and helper T cells provides a possible pathogenetic mechanism for the EBV-mediated coexistence of the two lymphomas. Here we summarized the cases of AITL-developed secondary EBV-associated B cell lymphoma and AITL/DLBCL CLs in Table 1. Among the patients mentioned above, the male to female ratio was 1.17:1, with their ages rang-ing from 36 to 90 years. Most of them were middle-aged and elderly people. The lesions were mainly in the lymph nodes, while a few happened in the gastrointestinal tract and skin. 25 patients among them had AITL/DLBCL composite lymphoma, and the rest were sec-ondary lymphoma, and the time interval between the two tumors ranged from three to fifty-six months. EBER was detected in 68.5% of all cases (25/36), and it shows the signifi-cant role EBV infection plays in the develop-ment of this disease, but it is clinically impracti-cal to biopsy all enlarged lymph nodes to increase the detection rate of EBER [15]. Among the 23 cases reported by QX et al. [17], clonal IgH gene rearrangement was positive in 66.7% (15/23) of them, while it counted for 70.6% (16/23) in yhr clonal TCR gene rear-rangement. So the molecular pathologic exami-nation combined with immunohistochemistry and morphological analysis were indispensable in the diagnosis of this disease.

chemo-therapy, targeted chemo-therapy, immunomodulatory therapy, and hematopoietic stem cell trans-plantation, but no standard treatment for this aggressive disease have yet been defined [7]. Chemotherapy based on anthracycline is the front-line treatment currently. AITL has a good response to chemotherapy, but it still has a high rate of early relapse, and the five-year overall survival (OS) rate is 32%-33%. The com-bined regimen consists of chemotherapy, tar-geted therapy, and immunomodulation, which can promote disease remission to permit hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

High-dose therapy with autologous stem cell transplantation (HDT-ASCT) is a salvage thera-py for AITL. Kyriakou et al. [27] reported their experiences with 19 patients diagnosed with AITL and subjected to HDT-ASCT., This group reported a complete remission (CR) rate of 79% after HDT-ASCT, and the OS at 5-year was 55%, but, unfortunately, the relapse rate (RR) after ASCT is exceedingly high (50% at 2 years). Rodriguez et al. [28] retrospectively reviewed AITL patients who were treated with HDT-ASCT from 1992 to 2004. The results showed that more than 50% of the patients achieved a dis-ease-free survival (DFS) of over 3 years after ASCT. The timing of the transplantation and the sensitivity of the patient to chemotherapy were two major factors influencing the outcome of the transplantation. Patients who received ASCT at the stage of either disease recurrence or when lymphoma affected the bone marrow would have a poor outcome. In addition, CR at 4 years in patients who were sensitive to che-motherapy was 30%, but it was only 23% in patients who were resistant to chemotherapy [27]. Accordingly, allo-HSCT was applied to patients who failed with ASCT, and the OS rate at 3 years was 64%, while the non-relapse mor-tality (NRM) within 1 yr was 25%, which was higher in patients with a poor physical status [29]. In our case, the patients failed to achieve CR after undergoing 5 courses of multiple che-motherapy and developed a rapid disease pro-gression of bone marrow infiltration; all these indicated a poor prognosis with ASCT. There- fore, a reduced-intensity conditioning HLA-haploidentical allo-HSCT should be carried out. Promisingly, the patient still remains CR after a year of regular follow-up.

In conclusion, we presented a rare case of AITL/DLBCL composite lymphoma in a patient

who underwent reduced-intensity conditioning HLA-haploidentical allo-HSCT and finally ac- hieved a satisfactory result. This case empha-sizes the interaction between immune dysfunc-tion and EBV infecdysfunc-tion, and EBV is etiologically related to this uncommon composite lympho-ma; in addition, allo-HSCT should be recom-mended to chemotherapy-insensitive patients as early as possible. AITL/DLBCL composite lymphoma is a rare tumor, which needs further studies to develop effective regimens and improve the clinical outcome for the patients diagnosed with it.

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

Address correspondence to: Guifang Ouyang, De-

partment of Hematology, The Affiliated Ningbo

Hos-pital of Zhejiang University, No. 59 Liuting Street, Haishu District, Ningbo 315000, Zhejiang, China. Tel: 13968710405; Fax: 0574-87291583; E-mail: nbougf@163.com

References

[1] Swerdiow SH, Campo E, Harris NL. World

health organization classification of tumours

of heamatopoietic and lymphoid tissues. 4th edition. Lyon: IARC Press; 2008; pp. 243-244. [2] Mosalpuria K, Bociek RG, Vose JM.

Angioim-munoblastic T-Cell lymphoma management. Semin Hematol 2014; 51: 52-58.

[3] Yachoui R, Farooq N, Amos JV, Shaw GR. Angio-immunoblastic T-Cell lymphoma with polyar-thritis resembling rheumatoid arpolyar-thritis. Clin Med Res 2016; 14: 159-162.

[4] Kim CH, Lim HW, Kim JR, Rott L, Hillsamer P, Butcher EC. Unique gene expression program of human germinal center T helper cells. Blood 2004; 104: 1952-1960.

[5] Yang HS, Zhang TH, Chen LL. EBV positive an-gioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma: clinico-pathological analysis of one case. Chin J Clini-cians (Electionic Edition) 2016; 10: 1774-1779. [6] Tokunaga T, Shimada K, Yamamoto K, Chihara

D, Ichihashi T, Oschima R, Tanimoto M, Iwasaki T, Isoda A, Sakai A, Kobayashi H, Kitamura K, Matsue K, Taniwaki M, Tanashima S, Saburi Y, Masunari T, Naoe T, Nakamura S, Kinoshita T. Retrospective analysis of prognostic factors for angioimmunoblastic T cell lymphoma: a multi-center cooperative study in Japan. Blood 2012; 119: 2837-2843.

of angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma: one case report and literatures. Chin J Hematol 2016; 37: 620-623.

[8] Suefuji N, Niino D, Arakawa F, Karube K, Kimu-ra Y, Kiyasu J, Takeuchi M, Miyoshi H, Yoshida M, Ichikawa A, Sugita Y, Ohshima K. Clinico-pathological analysis of a composite lym-phomacontaining both T- and B-cell lympho-mas. Pathol Int2012; 62: 690-698.

[9] Campidelli C, Sabattini E, Piccioli M, Rossi M, De Blasi D, Miraglia E, Rodriguez-Abreu D, Franscini LL, Bertoni F, Mazzucchelli L, Cavalli F, Zucca E, Pileri SA. Simultaneous occurrence

of peripheral T-cell imphomaun specified and

B-cell small lymphocytic lymphoma. Report of 2 case. Hum Pathol 2007; 389: 787-792. [10] Zhou Y, Rosenblun Mk, Dogan A, Jungbluth AA,

Chiu A. Cerebellar EBV-associated diffuse large B cell lymphoma following angioimmuno-blastic T cell lymphoma. J Hematop 2015; 8: 235-241.

[11] Dunleavy K, Wilson WH, Jaffe ES. Angioimmu-noblastic T cell lymphoma: pathobiological in-sights and clinical implications. Curr Opin He-matol 2007; 14: 348-353.

[12] Ishibuchi H, Motegi S, Yamanaka M, Amano H, Ishikawa O. Methotrexate-associated lymphop-roliferative disorder: sequential development of angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma-like lymphoproliferation in the lymph nodes and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in the skin in the same patient. Eur J Dermatol 2015; 25: 361-362.

[13] Wang Y, Xie B, Chen Y, Huang Z, Tan H. Devel-opment of angioimmunoblastic T-cell lympho-ma after treatment of diffuse large B-cell lym-phoma: a case report and review of literature. Int J Clin Exp Pathol 2014; 7: 3432-3438. [14] Smeltzer JP, Viswanatha DS, Habermann TM,

Patnaik MM. Secondary epstein-barr virus as-sociated lymphoproliferative disorder develop-ing in a patient with angioimmunoblastic t cell lymphoma on vorinostat. Am J Hematol 2012; 87: 927-928.

[15] Yang QX, Pei XJ, Tian XY, Li Y, Li Z. Secondary cutaneous epstein-barr virus-associated dif-fuse large B-cell lymphoma in a patient with angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma: a case report and review of literature. Diagn Pathol 2012; 7: 7.

[16] Tabata R, Tabata C, Yasumizu R, Kojima M. In-dependent growth of diffuse large B cell lym-phoma and angioimmunoblastic T cell lympho-ma originating from composite lympholympho-ma. Ann Hematol 2014; 93: 1801-1803.

[17] Huang J, Zhang PH, Gao YH, Qiu LG. Sequential development of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in a patient with angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma. Diagn Cytopathol 2012; 40: 346-351.

[18] Lee MH, Moon IJ, Lee WJ, Won CH, Chang SE, Choi JH, Lee MW. A case of cutaneous epstein-barr virus-associated diffuse large B-cell phoma in an angioimmunoblastic T-cell lym-phoma. Ann Dermatol 2016; 28: 789-791. [19] Zhou Y, Rosenblum MK, Dogan A, Jungbluth

AA, Chiu A. Cerebellar EBV-associated diffuse large B cell lymphoma following angioimmuno-blastic T cell lymphoma. J Hematop 2015; 8: 235-241.

[20] Suefuji N, Niino D, Arakawa F, Karube K, Kimu-ra Y, Kiyasu J, Takeuchi M, Miyoshi H, Yoshida M, Ichikawa A, Sugita Y, Ohshima K. Clinico-pathological analysis of a composite lym-phomacontaining both T- and B-cell lympho-mas. Pathol Int2012; 62: 690-698.

[21] Skugor ND, Peric Z, Vrhovac R, Radic-Kristo D, Kardum-Skelin I, Jaksic B. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in patient after treatment of angio-immunoblastic T-cell lymphoma. Coll Antropol 2010; 34: 241-245.

[22] Shinohara A, Asai T, Izutsu K, Ota Y, Takeuchi K, Hangaishi A, Kanda Y, Chiba S, Motokura T, Kurokawa M. Durable remission after the ad-ministration of rituximab for EBV-negative, dif-fuse large B-cell lymphoma following autolo-gous peripheral blood stem cell transplantation for angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma 2007; 48: 418-420.

[23] Hawley RC, Cankovic M, Zarbo RJ. Angioimmu-noblastic T-cell lymphoma with supervening epstein-barr virus-associated large B-cell lym-phoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2006; 130: 1707-1711.

[24] Xu Y, McKenna RW, Hoang MP, Collins RH, Kroft SH. Composite angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma and diffuse large B-T-cell lympho-ma: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Clin Pathol 2002; 118: 848-854. [25] Takahashi T, Maruyama R, Mishima S, Inoue

M, Kawakami K, Onishi C, Miyake T, Tanaka J, Nabika T, I shikura H. Small bowel perforation caused by epstein-barr virus-associated B cell lymphoma in a patient with angioimmunoblas-tic T-cell lymphoma. J Clin Exp Hematop 2010; 50: 59-63.

[26] Weisel KC, Weidmann E, Anagnostopoulos I, Kanz L, Pezzutto A, Subklewe M. Epstein-barr virus-associated B-cell lymphoma secondary to FCD-C therapy in patients with peripheral T-cell lymphoma. Int J Hematol 2008; 88: 434-440.

the european group for blood and marrow transplantation. J Clin Oncol 2008; 26: 218-224.

[28] Rodriguez J, Conde E, Gutierrez A, Arranz R, Gandarillas M, Leon A. Prolonged survival of patients with angioimmunoblastic T-cell lym-phoma after high-dose chemotherapy and au-tologous stem cell transplantation. The GEL-TAMO experience. Eur J Haematol 2007; 78: 290-296.