Racial Differences in Choice of Dialysis Modality for Children With

End-stage Renal Disease

Susan L. Furth, MD*‡; Neil R. Powe, MD, MPH, MBA‡§i¶#; Wenke Hwang, MS¶#; Alicia M. Neu, MD*; and Barbara A. Fivush, MD*

ABSTRACT. Objective. Black-white disparities in the use of specific medical and surgical services have been reported in adult populations. Such disparities are not well documented in children. We sought to determine whether racial disparities in the use of medical services exist among children with chronic illness who have sim-ilar health insurance, specifically the choice of dialysis modality for individuals with end-stage renal disease.

Design. National cross-sectional study.

Setting. Outpatient dialysis facilities throughout the United States.

Patients and Participants. All Medicare-eligible chil-dren (age, 19 years) undergoing renal replacement ther-apy in 1990 in the United States, using data from the Medicare ESRD registry.

Outcome Measures. The odds of receiving hemodialy-sis versus peritoneal dialyhemodialy-sis according to race. Adjust-ment was made for differences in age, gender, cause, and duration of end-stage renal disease, income, education, and facility chracteristics using multiple logistic regres-sion.

Results. In 1990, 870 white and 368 black children received chronic (>1 year) renal replacement therapy in the United States. In bivariate analysis, blacks were two times (odds ratio [OR], 2.2; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.7, 2.8) more likely than whites to receive hemodialysis versus peritoneal dialysis. After controlling for other pa-tient and facility characteristics in multivariate analysis, black children were still significantly more likely than white children to receive hemodialysis (OR, 2.4; 95% CI, 1.7, 3.5).

Conclusions. Black race is strongly associated with the use of hemodialysis in children. Family, patient, or pro-vider preferences could account for the difference in choice of therapy by race. Pediatrics 1997;99(4). URL: http://www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/99/4/e6; chronic renal failure, children; racial disparities, perito-neal dialysis, health insurance.

ABBREVIATIONS. ESRD, end-stage renal disease; HD, hemodi-alysis; PD, peritoneal dihemodi-alysis; RRT, renal replacement therapy.

In 1990, the Council on Ethical and Judicial Affairs of the American Medical Association called for the elimination of racial disparities in medical treatment decisions in the United States.1 They urged physi-cians to examine their own practices and for the profession to “increase the awareness of racial dis-parities in medical treatment decisions through broad discussion of the issue.”1 While black-white disparities in treatment options have been previously documented in adults, particularly in nephrology,2,3 cardiology,4cardiac surgery,5obstetrics,1and general internal medicine,6this issue has not been explored fully in populations cared for by general or subspe-cialty pediatricians.7Black-white disparities in use of medical services can be confounded by differences in health insurance status making this issue difficult to examine. One population in which primary health insurance differences do not exist is in end-stage renal disease (ESRD) patients covered by Medicare insurance.

Recently, lower rates in initiation of peritoneal dialysis (PD) for black versus white adult patients with ESRD have been reported in a cohort from the Southeastern United States.2 Although transplanta-tion remains the preferred treatment modality for children with ESRD,8many children with ESRD un-dergo a period of chronic maintenance dialysis9 be-fore transplantation or after a failed transplant. Un-fortunately, because of multiple complicating factors, some children may not be candidates for transplan-tation, or may spend years waiting for a suitable organ. Although the ideal method of dialysis for the pediatric age group is subject to debate, and few studies have compared the morbidity and mortality of hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis in an objec-tive and rigorous fashion, home peritoneal dialysis is widely regarded as the optimal form of renal replace-ment therapy (RRT).10In a prior observational study in which patients were allowed to choose their own treatment modality, PD was associated with better growth than hemodialysis.11 Improved metabolic control and more liberal diets have also been cited as benefits of PD in observational studies.12 Opportu-nity for improved school attendance has also been cited as a benefit of PD.10,12 Ultimate rehabilitation may also be more favorable, as children on PD dem-onstrate improved psychosocial coping skills and less depression.13,14

A recent report from a selected group of pediatric nephrologists9showed that while 73% of white chil-From the *Division of Pediatric Nephrology, Department of Pediatrics;

‡Renal Disease Epidemiology Training Program, §Department of Medicine;

iDepartments of Epidemiology, and ¶Health Policy and Management, Johns Hopkins School of Hygiene and Public Health, and the #Welch Center for Prevention, Epidemiology and Clinical Research, Johns Hopkins Medi-cal Institutions, Baltimore, Maryland.

Presented at the 28th annual meeting of the American Society of Nephrol-ogy, San Diego, CA.

Received for publication Apr 15, 1996; accepted Aug 27, 1996.

Reprint requests to (S.L.F.) Johns Hopkins Hospital, 600 N Wolfe St, Park 327, Baltimore, MD 21287–2535.

dren and adolescents utilized PD as their first mo-dality, only 60% of black children and adolescents were initiated on this therapy. In light of this initial observation, we chose to explore whether this racial disparity persisted in the broader total population of children with ESRD, and to examine whether poten-tial confounding factors beyond health insurance coverage such as age, cause and duration of ESRD, or socioeconomic status could explain the racial differ-ences seen in the choice of RRT for the pediatric population.

METHODS Study Design

We performed a national cross-sectional study of patients aged 0 to 19 years who had ESRD requiring RRT. Patients were in-cluded if they were#19 years old, if they were enrolled in the Medicare ESRD program (entitled to Medicare Part A services) at any time between January 1, 1989 and December 31, 1990 and they did not have a functioning transplant during the entire year. Patients were excluded if they did not receive their care at a single facility for more than 6 months, or if they were not on a single dialysis modality for at least 6 months of the year.

Data Sources and Variable Definition

Data from the Medicare ESRD Program Management and Med-ical Information System (PMMIS), which are assembled and main-tained by the Health Care Financing Administration (HCFA), were used to identify all prevalent pediatric patients (age,#19 years) enrolled in the United States ESRD program in 1990.

Our analysis used the PMMIS enrollment file containing the beneficiary identification code, date of first ESRD service, date of birth, sex, race (white, black, Asian, Native American, or other), cause of ESRD assigned by the patient’s nephrologist (Internation-al Classification of Diseases, Ninth revision, Clinic(Internation-al Modification codes [ICD-9-CM]), date of kidney transplantation, primary treat-ment facility (providing the majority of ESRD services), treattreat-ment facility ownership (for-profit or not-for-profit), facility affiliation (hospital based or free-standing), and facility ESRD network mem-bership. ICD-9-CM codes were grouped into 13 categories consist-ing of: (1) hypertension (410, 403, 404), (2) diabetes mellitus (250), (3) glomerulonephritis (GN), including categories of nephritis/ nephropathy, nephrotic syndrome, rapidly progressive and acute GN (580, 581, 582, 583), (4) polycystic kidney disease (753.1),(5) infectious (eg, chronic pyelonephritis 590), (6) lupus nephritis (695.4, 710), (7) metabolic (including disorders of amino acid trans-port and carbohydrate transtrans-port), (8) unknown cause, (9) other immune-mediated disorders including Henoch-Schonlein pur-pura, Wegener’s granulomatosis, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura, (10) hemolytic uremic syndrome, (11) congenital anom-alies, (12) urologic/obstructive abnormalities, and (13) all other causes (including acute tubular necrosis, AIDS, transplant compli-cations, and so forth). It should be noted that the categories of renal disease available in the database may be more appropriate for adult than pediatric ESRD patients, as causes of ESRD such as diabetes and hypertension, although common in adults, are rarely seen in children.

We also used quarterly dialysis records from the PMMIS con-taining data on the location and modality of dialysis treatment (in-center hemodialysis [HD], in-center PD, home HD, and home PD). Quarterly records were grouped by patient ID to identify patients who spent at least 6 months during 1990 on a single dialysis modality at a single facility.

The above data files were linked through the beneficiary’s zip code of residence to data from the 1990 national census. From the census, we obtained zip code-specific data on median household income, and race-specific education levels.

Patient age and ESRD duration were categorized as follows: age#4 years,.4 to#9 years,.9 to#14 years, and.14 to#19 years; duration ESRD#1 year,.1 and#2 years,.2 and#5 years, and.5 years. Zip code-specific median household incomes were grouped as #$20 000, .$20 000 and #$40 000, .$40 000 and #$60 000, and.$60 000, and were linked to the patient’s benefi-ciary identification as a marker of economic status. Similarly, the

percentage of residents of the same race, residing in the same zip code as the patient who achieved at least a high school education, was used as a measure of educational status.

The ESRD network in which patients received care were grouped geographically into Northeast (networks 1 to 5), South-east (6 to 8), Midwest (9 to 12), Southwest (13 to 15), and West (16 to 18).

Statistical Analysis

We examined the relationship between race and dialysis mo-dality for children with ESRD who were Medicare beneficiaries in 1990. Because patient characteristics other than race (eg, age, du-ration, assigned cause of ESRD, and socioeconomic factors) and facility traits (eg, hospital-based versus free-standing, for-profit or not-for profit status) may be associated with dialysis modality choice, we compared the HD group and the PD group with regard to each of these factors. For each independent variable, we con-structed 232 tables of the number of HD or PD patients with that particular trait, to calculate odds ratios and 95% confidence inter-vals for the association. This permitted us to examine associations among the independent variables to assess for the possibility of confounding. Possible confounders were then adjusted for by using multiple logistic regression analysis to examine the inde-pendent association of race with dialysis modality selection. Mul-tivariate analysis was performed using SAS statistical software.15

RESULTS Characteristics of Patients

There were 2387 children (#19 years) enrolled in the United States ESRD program in 1990. Dialysis data was available from the quarterly dialysis records on 1404 of these children, adolescents, and young adults. The 983 patients for whom dialysis information was missing were either preemptive transplant patients or patients still in the 3 month waiting period for Medicare eligibility.

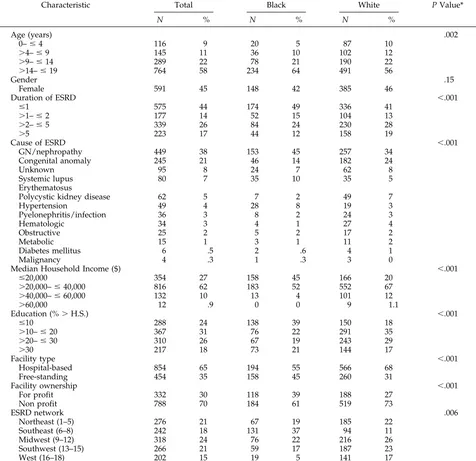

Of the 1404 children with dialysis data available, 1256 received their care at a single facility and on a single modality for more than 6 months in 1990. Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of all patients by racial group. Black children with ESRD were older than whites, and had ESRD for a shorter duration than whites. The mean household incomes of the zip codes in which black children lived were far lower than those of their white counterparts. The number of children who lived in zip codes where fewer than 10% of people of their race achieved greater than a high school education was greater for black children than for white children. Assigned cause of ESRD also differed by race, with blacks over-represented in the glomerulonephritis, lupus, and hypertension groups and whites over-repre-sented in categories of congenital renal anomalies and polycystic kidney disease. There were no differ-ences between black and white children in gender.

Facility characteristics also differed by race of the beneficiary. Whites were more likely than blacks to receive RRT at hospital-based and not-for-profit fa-cilities. As might be expected, a higher percentage of the black patients received care in the Southeastern United States.

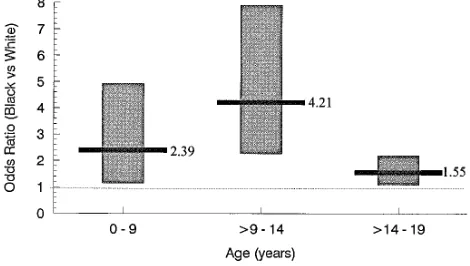

children to be on HD rather than PD. Children be-tween the ages of 9 to 14 years were more than four times more likely to be on HD than PD if they were black. In the 14 to 19 year age group, blacks were still 50% more likely to be maintained on HD rather than PD.

Because the association of race and modality choice may be confounded by additional patient chracteristics (Table 1) other than age, we also per-formed multivariate analysis. The results of multi-variate analysis of HD versus PD are presented in Table 2. Older age groups were increasingly likely to be on HD over PD as reflected in the bivariate anal-ysis. Patients who had ESRD for longer than 5 years were 50% more likely to be on HD rather than PD. Even after controlling for patient age, gender, dura-tion and assigned cause of ESRD, socioeconomic

fac-tors, and facility characteristics, black children with ESRD were almost two and one-half times more likely to be on HD than were white children.

DISCUSSION

Our study describes significant differences in dial-ysis modality choice for children with ESRD by racial group. These disparities persist even after important demographic and socioeconomic differences are taken into account. These findings are consistent with reports of racial differences in RRT in adults, but appear more striking because PD in children is widely regarded, although not proven, to be the preferred form of RRT.

Before our study, racial differences in age were thought to explain the racial discrepancies in modal-ity choice, since older children are more likely to be TABLE 1. Characteristics of Dialysis-dependent Children With ESRD: Overall and by Race

Characteristic Total Black White P Value*

N % N % N %

Age (years) .002

0–#4 116 9 20 5 87 10

.4–#9 145 11 36 10 102 12

.9–#14 289 22 78 21 190 22

.14–#19 764 58 234 64 491 56

Gender .15

Female 591 45 148 42 385 46

Duration of ESRD ,.001

#1 575 44 174 49 336 41

.1–#2 177 14 52 15 104 13

.2–#5 339 26 84 24 230 28

.5 223 17 44 12 158 19

Cause of ESRD ,.001

GN/nephropathy 449 38 153 45 257 34

Congenital anomaly 245 21 46 14 182 24

Unknown 95 8 24 7 62 8

Systemic lupus 80 7 35 10 35 5

Erythematosus

Polycystic kidney disease 62 5 7 2 49 7

Hypertension 49 4 28 8 19 3

Pyelonephritis/infection 36 3 8 2 24 3

Hematologic 34 3 4 1 27 4

Obstructive 25 2 5 2 17 2

Metabolic 15 1 3 1 11 2

Diabetes mellitus 6 .5 2 .6 4 1

Malignancy 4 .3 1 .3 3 0

Median Household Income ($) ,.001

#20,000 354 27 158 45 166 20

.20,000–#40,000 816 62 183 52 552 67

.40,000–#60,000 132 10 13 4 101 12

.60,000 12 .9 0 0 9 1.1

Education (%.H.S.) ,.001

#10 288 24 138 39 150 18

.10–#20 367 31 76 22 291 35

.20–#30 310 26 67 19 243 29

.30 217 18 73 21 144 17

Facility type ,.001

Hospital-based 854 65 194 55 566 68

Free-standing 454 35 158 45 260 31

Facility ownership ,.001

For profit 332 30 118 39 188 27

Non profit 788 70 184 61 519 73

ESRD network .006

Northeast (1–5) 276 21 67 19 185 22

Southeast (6–8) 242 18 131 37 94 11

Midwest (9–12) 318 24 76 22 216 26

Southwest (13–15) 266 21 59 17 187 23

West (16–18) 202 15 19 5 141 17

* Difference in characteristic between black and white patients fromx2. For ordered categories,x2test for trend was utilized. GN5

treated with HD, and black children with renal fail-ure are on the whole, older than whites.9However, using multivariate techniques, we were able to doc-ument that the racial differences in modality choice persisted even after controlling for age. In addition, controlling for differences in clinical characteristics, geography, socioeconomic status, and facility factors potentially associated with the race of the patient, did not lessen the association between black race and the use of HD in children with ESRD.

The observation by Held and colleagues16that dif-ferences in access to kidney transplantation among different sociodemographic groups exist has led to several studies establishing the fact that access to organ transplantation is not completely separable from the income, race, and other sociodemographic characteristics of the recipient.17,18Prior studies have also highlighted differences in the use of invasive procedures for ischemic heart disease by race.4 A recent report on ethnic differences in the use of PD for ESRD in adults2revealed that black-white differ-ences in initial PD use could not be explained by many demographic, socioeconomic, or co-morbid factors. The authors suggested that cultural differ-ences in health care beliefs or self-perception might explain varying patient preferences in dialysis mo-dality choice by race. The possibility of systematic bias on the part of providers could not be ruled out as playing a role in the observed association. The consistent finding of an association between treat-ment decisions and race across these studies across several medical disciplines argues against the asso-ciation being spurious.

Our study has many strengths. First, the study population was national, including all pediatric pa-tients enrolled in the Medicare ESRD program dur-ing one calendar year, regardless of provider affilia-tion. Second, study of the Medicare ESRD program allows a unique opportunity to examine ethnic dif-ferences in health care received under conditions where the effect of health insurance on access to care is less of an issue than it might be for other diseases. Because of the availability of Medicare to pay for renal replacement therapy in children with ESRD, it is unlikely that ability to pay for dialysis could have accounted for our results. Furthermore, the linkage of data from the 1990 census allowed us to utilize

national zip code-based demographic information to adjust for income and education, important potential socioeconomic confounders in examining the effect of race on choice of therapy.

Our study also has several limitations. Perhaps most importantly, we were unable to capture the effect of prior switches in dialysis modality. For ex-ample, if a patient’s initial RRT modality was PD but membrane failure or recurrent peritonitis necessi-tated conversion to HD before 1990, that patient would be categorized as a HD patient. If these clin-ical factors are more commonly associated with black race even after adjustment for socioeconomic status, our results would not account for these differences. We also were unable to adjust for co-existing mor-bidity, as this may also impact on dialysis modality choice. This is an important factor in adult studies of dialysis modality choice; however, it may not be as crucial in pediatrics, as there are few conditions other than abdominal wall defects and membrane failure that are absolute contraindications to the use of PD in children.19

In addition, adjusting for socioeconomic status on the basis of zip code-based census data may not be as desirable as using patient specific income or educa-tion. However, recent studies have provided evi-dence that zip code-based measures of socioeco-nomic status are robust and reliable proxies for patient socioeconomic conditions.20

Our study may not be generalizable to a particular segment of children who are not eligible for Medi-care. If neither parent has worked and contributed to social security, a child cannot become a Medicare beneficiary. In addition, for the first 18 months of dialysis, a patient’s primary insurance is responsible for payment. After this time period, Medicare be-comes the primary health insurer. Patients with Medicare as primary insurance are responsible for approximately 20% of payments, since Medicare cov-ers 80% of outpatient services. However, this is un-likely to have affected our results, since this 80% Figure. Association of black race with use of hemodialysis

ver-sus peritoneal dialysis by age group. Black line represents point estimate, shaded bar represents 95% confidence interval.

TABLE 2. Association of Patient Characteristics With Dialysis Modality (Hemodialysis vs Peritoneal Dialysis)

Characteristic Unadjusted Odds Ration (95% CI)

Adjusted* Odds Ratio (95% CI)

Race

White 1.0 (reference) 1.0 (reference) Black 2.2 (1.7, 2.8) 2.4 (1.7, 3.5) Age (years)

#4 1.0 (reference) 1.0 (reference)

.4–#9 1.1 (.8, 1.3) .9 (.4, 1.9)

.9–#14 2.8 (1.7, 4.6) 1.8 (1.0, 3.4)

.14–#19 5.8 (3.6, 9.2) 3.9 (2.2, 6.9) Gender

Female 1.0 (reference) 1.0 (reference) Male 1.0 (.8, 1.3) 1.1 (.9, 1.5) Duration of ESRD

#1 1.0 (reference) 1.0 (reference)

.1–#2 .9 (.6, 1.2) .9 (.6, 1.4)

.2–#5 .9 (.7, 1.2) .9 (.6, 1.3)

applies for both PD and HD services and we ad-justed for duration of ESRD.

In this analysis, although we adjusted for the ESRD network of the provider as a geographic indi-cator, the distance from a patient’s home to their dialysis center and the modalities offered at that center were not taken into account. Living in a rural or urban center may certainly impact dialysis modal-ity choice, and the geographic distribution of black and white ESRD patients may impact modality choice in ways unmeasured by our study.

A final limitation of this cross-sectional study uti-lizing existing administrative data, is that individual patient and family preferences and their impact on dialysis modality choice could not be measured. In-deed, there may be distinct advantages for certain patient groups in choosing in-center versus home dialysis treatments. In addition, it is interesting to note that more blacks are treated at free-standing, for-profit facilities. This may reflect more for-profit dialysis facilties locating in urban centers, where larger numbers of black patients live. More informa-tion on patient and family preferences and the set-tings in which dialysis care is provided might en-lighten us on why differential access to PD exists by race.

Why do disparities in the use of HD and PD persist in black and white patients? Possible explanations include unmeasured differences in socioeconomic status, differences in co-morbid conditions or modal-ity switches, cultural differences in attitudes toward or preferences for peritoneal and hemodialysis, dif-ferences in access to care, or systematic racial bias. Any or all of these factors may contribute to the difference in dialysis modality choice which we observed.

The extent to which subtle provider preconcep-tions about race affect dialysis modality choice in children is unclear. Determining whether provider bias, patient or family preference, co-morbid condi-tions or residual socioeconomic or geographic con-founders are responsible for the preponderant use of HD in black children with ESRD will require studies which address these possible confounders more pre-cisely, and directly examine the interactions and “participatory decision making”21 between patients and their physicians. Our cross-sectional analysis could lay the groundwork for a prospective study to examine more precisely clinical, cultural or socioeco-nomic factors responsible for the discrepancy in ac-cess to care for children with ESRD.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Supported in part by grant #HS08365 from the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, Rockville, MD, grant #DK07732– 01 from the National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive

and Kidney Disorders, and a mini-grant from the National Kidney Foundation of Maryland. Computational assistance was received from the COMAS of the General Clinical Research Center and the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, sponsored by NIH grants RR00035 and RR00722.

REFERENCES

1. Council on Ethical and Judicial Affairs. Black-white disparities in health care. JAMA. 1990;263:2344 –2346

2. Barker-Cummings C, McClellan W, Soucie JM, Krisher J. Ethnic differ-ences in the use of peritoneal dialysis as initial treatment for end stage renal disease. JAMA. 1995;274:1858 –1862

3. Kjellstrand CM. Age, sex and race inequality in renal transplantation.

Arch Intern Med. 1988;148:1305–1309

4. Whittle J, Conigliaro J, Good CB, Lofgren RP. Racial differences in the use of invasive cardiovascular procedures in the Department of Veter-ans Affairs medical system. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:621– 627

5. Goldberg KC, Hartz AJ, Jacobsen SJ, Krakauer H, Rim AA. Racial and community factors influencing coronary artery bypass graft surgery rates for all 1986 Medicare patients. JAMA. 1992;267:1473–1477 6. Eisenberg JM. Sociologic influences on decision-making by clinicians.

Ann Intern Med. 1979;90:957–964

7. Levy DR. White doctors and black patients. Influence of race on the doctor patient relationship. Pediatrics. 1985;75:639 – 643

8. US Renal Data System. USRDS 1995 Annual Data Report. The National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, Bethesda, MD. Am J Kidney Dis. 1995;26:S112–S128 9. Avner ED, Chaver B, Sullivan EK, Tejani A. Renal transplant and

chronic dialysis in children and adolescents: the 1993 annual report of the North American Pediatric Renal Transplant Cooperative Society.

Pediatr Nephrol. 1995;9:61–73

10. Fine RN, Salusky IB, Ettenger RB. Therapeutic approach to the infant, child, and adolescent with ESRD. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1987;34: 789 – 801

11. Kaiser BA, Polinsky MS, Stover J, Morgenstern BZ, Baluarte HJ. Growth of children following the initiation of dialysis: a comparison of three modalities. Pediatr Nephrol. 1994;8:733–738

12. Baum M, Powell D, Calvin S, McDaid T, McHenry K, Mar H, Potter D. Continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis in children. N Engl J Med. 1982;307:1537–1542

13. Brem AS, Brem FS, McGrath M, Spirito A. Psychosocial characteristics and coping skills in children maintained on chronic dialysis. Pediatr

Nephrol. 1988;2:460 – 465

14. Brownbridge G. Fielding DM. Psychosocial adjustment to end stage renal failure: comparing hemodialysis, chronic ambulatory peritoneal dialysis and transplantation. Pediatr Nephrol. 1991;5:612– 616

15. SAS Institute Inc. SAS Procedures Guide: Version 6.03 Edition. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc; 1988

16. Held PJ, Pauly MV, Bovberg RR, Newman J, Salvaterra O. Access to kidney transplantation: has the US eliminated income and racial differ-ences? Arch Intern Med. 1988;148:2594 –2600

17. Kasiske BL, Neylan JF, Riggio RR, Danovitch GM, Kahasas L, Alexander SK, White MG. The effect of race on access and outcome in transplan-tation. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:302–307

18. Gaylin DS, Held PJ, Port FK, Hunsicker LG, Wolfe RA,Kahan BD, Jones CA, Agodoa LYC. The impact of comorbid and sociodemographic factors on access to renal transplantation. JAMA. 1993;269:603– 608 19. Harvey E, Secker D, Braj B, Picone G, Balfe JW. The team approach to

the management of children on chronic peritoneal dialysis. Adv Renal

Replacement Ther. 1996;3:3–13

20. Krieger N. Overcoming the absence of socioeconomic data in medical records: validation of a census-based methodology. Am J Public Health. 1992;82:703–710

21. Kaplan SH, Greenfield S, Gandek B, Rogers WH, Ware JE. Character-istics of physicians and participatory decision making styles. Ann Intern

DOI: 10.1542/peds.99.4.e6

1997;99;e6

Pediatrics

Susan L. Furth, Neil R. Powe, Wenke Hwang, Alicia M. Neu and Barbara A. Fivush

Disease

Racial Differences in Choice of Dialysis Modality for Children With End-stage Renal

Services

Updated Information &

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/99/4/e6

including high resolution figures, can be found at:

References

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/99/4/e6#BIBL

This article cites 20 articles, 1 of which you can access for free at:

Permissions & Licensing

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/Permissions.xhtml

entirety can be found online at:

Information about reproducing this article in parts (figures, tables) or in its

Reprints

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/reprints.xhtml

DOI: 10.1542/peds.99.4.e6

1997;99;e6

Pediatrics

Susan L. Furth, Neil R. Powe, Wenke Hwang, Alicia M. Neu and Barbara A. Fivush

Disease

Racial Differences in Choice of Dialysis Modality for Children With End-stage Renal

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/99/4/e6

on the World Wide Web at:

The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is located

American Academy of Pediatrics. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 1073-0397.