A Content Analysis of E-mail Communication Between Primary Care

Providers and Parents

Shikha G. Anand, MD*; Mitchell J. Feldman, MD‡; David S. Geller, MD‡; Alice Bisbee, MPH§; and Howard Bauchner, MD*

ABSTRACT. Background. E-mail exchange between

parents of patients and providers has been cited by the Institute of Medicine as an important aspect of contem-porary medicine; however, we are unaware of any data describing actual exchanges.

Objective. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the content of e-mails between providers and parents of patients in pediatric primary care, as well as parent atti-tudes about e-mail.

Design/Methods. Over a 6-week period, all e-mail ex-changes between 2 primary care pediatricians and their patients’ parents were evaluated and coded. An exchange was defined as the e-mails between parent and primary care provider about a single inquiry. Parents also com-pleted a questionnaire regarding this service.

Results. Of 55 parents, 54 (98%) agreed to have their e-mails with their pediatrician reviewed. The 54 parents generated 81 mail exchanges; 86% required only 1 e-mail response from the pediatrician, and the other 14% required an average of 1.9 responses. E-mail inquiries were all for nonacute issues (as judged by S.G.A.) and included inquiries about a medical question (nⴝ 43), medical update (nⴝ20), subspecialty evaluation (nⴝ9), and administrative issue (nⴝ 9). The 81 exchanges re-sulted in 9 appointments, 21 phone calls, 4 subspecialty referrals, 34 prescriptions or recommendations for over-the-counter medications, 11 administrative tasks, and 1 radiograph. Of 91 pediatrician-generated e-mails, 39% were sent during the workday (9AMto 5PM, Monday to Friday), 44% were sent on weeknights, and 17% were sent on weekends. During the study period, the 2 physicians estimated an average of 30 minutes/day spent responding to e-mail. Of the 54 parents, 45 (83%) returned the survey; 93% were mothers and 86% had completed college. Nine-ty-eight percent were very satisfied with their e-mail experience with their pediatrician. Although 80% felt that all pediatricians should use e-mail to communicate with parents and 65% stated they would be more likely to choose a pediatrician based on access by e-mail, 63% were unwilling to pay for access.

Conclusions. This is the first study to describe actual e-mail exchange between parents and their providers.

Exchanges seem to be different from those generated by the telephone, with more e-mails related to medical ver-sus administrative issues and more resulting in office visits. Approximately 1 in 4 exchanges result in multiple e-mails back and forth between parent and provider. Parents who have actually exchanged e-mails with their providers overwhelmingly endorse it, although they are reluctant to pay for it.Pediatrics2005;115:1283–1288;

e-mail, computers, primary care.

ABBREVIATION. IOM, Institute of Medicine.

T

he Institute of Medicine (IOM), in its report Crossing the Quality Chasm, articulates 6 specific aims for a 21st-century health care system.1 Care should be safe, effective, efficient, equitable, timely, and patient centered. As part of patient-cen-tered care, the IOM specifically includes e-mail ex-changes between care providers and patients as an important ingredient in a modern health care system. In addition to the IOM, many other leading health care experts have echoed the importance of e-mail.2–8 Benefits include improved patient-physician com-munication, enhanced patient-centered care, reduced cost, and continuous monitoring of clinical status, especially for patients with chronic conditions. Unique features of e-mail include its asynchronous nature, allowance for essentially continuous access to the health care system, full written record of com-munication with patients, and the ability to embed written and Internet resources for additional medical information when addressing a medical question.E-mail stands in contrast to the telephone. Cur-rently, the vast majority of nonvisit care is conducted by telephone. However, physicians spend an average of 60 minutes/day on the telephone, with much of this being “wasted time” (on hold or failing to make contact [M.J. Feldman, MD, written communication, May 25, 2004]). Patients also have complaints about telephone communication, with virtually all patients having difficulty reaching their doctors by telephone and many having given up trying.9

Despite numerous surveys and editorials,5,10–14we are unaware of any published study that has de-scribed e-mail exchanges between parents and pri-mary care pediatricians. The purpose of this study was to document and analyze all e-mail communi-cation between 2 private pediatricians and the par-ents of their patipar-ents over a 6-week period and to From the *Division of General Pediatrics, Boston University School of

Medicine, ‡Harvard Medical School, and §Boston University School of Public Health, Boston, Massachusetts.

Accepted for publication Sep 7, 2004. doi:10.1542/peds.2004-1297

This work was presented in part at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies; May 2, 2004; San Francisco, CA.

No conflict of interest declared.

Address correspondence to Shikha G. Anand, MD, Boston Medical Center, 91 E Concord St, Maternity Building, Boston, MA 02118. E-mail: shikha. anand@bmc.org

survey parents regarding their actual experiences with e-mail use in this context.

METHODS

This study was conducted in a pediatric private practice in suburban Massachusetts in which 2 of 3 pediatricians allow par-ents to communicate with them by e-mail. Both physicians allow e-mail access to every parent from the first visit onward. The 2 pediatricians included in the study are male and between the ages of 35 and 45 years. The practice is a general pediatric private practice that currently includes⬃4700 patients. Parents of patients are mostly white, privately insured, and well educated.

The study was conducted from October 1, 2003, to November 14, 2003. During that time, each e-mail from parent to physician generated a standardized response from the physician requesting study participation. Once consent was obtained, all e-mail com-munication between parent and provider, including the initial e-mail, was forwarded to the principal investigator of the study. In addition, a 45-item questionnaire was e-mailed to each parent enrolled in the study after documentation of consent. Reminders were sent to nonresponders by e-mail at 3 and 6 weeks after initiation of an encounter.

An encounter was defined as the group of e-mail exchanges between pediatrician and parent surrounding a single medical issue. Each e-mail exchange consisted of a single parent e-mail and a single provider response. Groups of issues were only coded as a single encounter if they were mentioned together in the initial parent e-mail. Each encounter was coded as a single unit consist-ing of multiple e-mails. Documentation of consent and expres-sions of thanks were omitted from the total number of e-mails per encounter.

E-mail outcomes were categorized based on the nomenclature developed by Poole and Glade14in a content analysis of telephone

use in pediatric primary care. Medical updates were defined as information on a clinical condition previously discussed. Subspe-cialty updates were used by the parent to alert the pediatrician on the progress of care by pediatric subspecialists. Medications in-cluded both prescription and over-the-counter medications rec-ommended by the pediatrician. Physician health questions in-cluded those regarding specific medical questions and those addressing child behaviors and safety. Administrative issues were defined as those resulting in letters from the pediatrician on behalf of the patient to third parties such as insurance providers and adoption agencies.

This study was approved by the institutional review boards of Boston University School of Medicine and the Boston Medical Center.

RESULTS E-mails

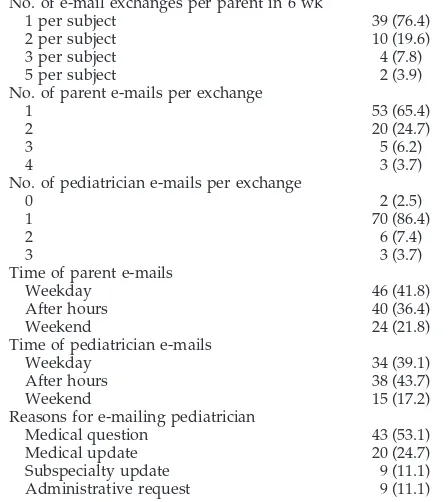

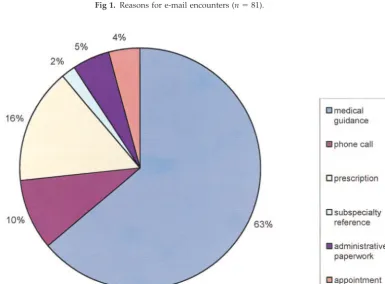

Of 55 parents, 54 (98%) agreed to have the e-mails with their pediatrician reviewed. The 54 parents gen-erated 81 e-mail exchanges (Table 1). Seventy (86%) required only 1 e-mail response from the pediatri-cian, whereas the other 11 (14%) required an average of 1.9 responses from the pediatrician (see Fig 1). (E-mail inquiries were all for nonacute issues [as judged by S.G.A.] and included medical questions [n ⫽ 43] and queries about medical updates [n ⫽ 20], subspecialty evaluations [n⫽9], and administrative issues [n⫽9]). One parent included a digital photo-graph of her child’s rash, which prevented an office visit for examination of the rash. The 81 exchanges resulted in 9 appointments (including 6 for the influ-enza vaccine), 21 phone calls, 4 subspecialty refer-rals, 34 prescriptions or recommendations for over-the-counter medications, 11 administrative tasks, and 1 radiograph (see Fig 2). In addition, 8 of the provider e-mails contained an embedded selection from practice guidelines or the literature or an Inter-net link to additional information. Of 91

physician-generated e-mails, 39% were sent during the work-day (9:00 am to 5:00 pm, Monday to Friday), 44% were sent on weeknights (5:01pm to 8:59am, Mon-day to ThursMon-day), and 17% were sent on weekends (5:01 pm Friday to 8:59 am Monday). During the study period, the 2 physicians estimated an average of 30 minutes/day spent responding to e-mail.

Survey

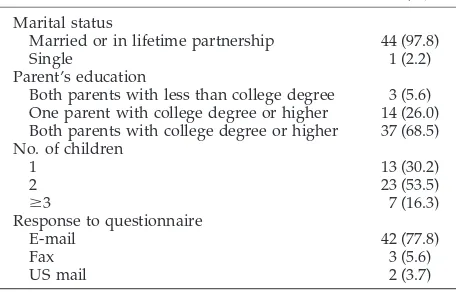

Of the 54 parents, 45 (83%) returned the survey, with 78% of surveys returned by e-mail (see Table 2). The majority of respondents were mothers (93%), married or in a lifetime partnership (98%), and in families with at least 1 parent having completed college (94%) (see Table 2). Almost half of the moth-ers had access to e-mail at both home and work. Most used e-mail daily, 75% estimated that they e-mailed their pediatrician 1 to 3 times during the past month, and ⬃1 of 3 e-mailed their pediatrician ⬎7 times in the past year (Table 3). Ninety-eight percent of re-spondents stated that their experience e-mailing their pediatricians had been very good or great (Table 4). When asked, parents stated that the majority of e-mail contact with pediatricians was surrounding medical issues (81%), with only 14% e-mailing for administrative requests and 5% for prescription re-quests. Although 80% felt that all pediatricians should use e-mail to communicate with parents and 65% stated they would be more likely to choose a pediatrician based on access by e-mail, 63% were unwilling to pay for access (Table 4).

DISCUSSION

We believe that this is the first study to examine the actual content of e-mail exchanges between par-ent and pediatrician in the primary care domain.

TABLE 1. Characteristics of E-mail Encounters

n(%)

No. of e-mail exchanges per parent in 6 wk

1 per subject 39 (76.4)

2 per subject 10 (19.6)

3 per subject 4 (7.8)

5 per subject 2 (3.9)

No. of parent e-mails per exchange

1 53 (65.4)

2 20 (24.7)

3 5 (6.2)

4 3 (3.7)

No. of pediatrician e-mails per exchange

0 2 (2.5)

1 70 (86.4)

2 6 (7.4)

3 3 (3.7)

Time of parent e-mails

Weekday 46 (41.8)

After hours 40 (36.4)

Weekend 24 (21.8)

Time of pediatrician e-mails

Weekday 34 (39.1)

After hours 38 (43.7)

Weekend 15 (17.2)

Reasons for e-mailing pediatrician

Medical question 43 (53.1)

Medical update 20 (24.7)

Subspecialty update 9 (11.1)

Others have previously reported on e-mail consulta-tion in a pediatric gastroenterology practice6 and internal medicine practice.15,16 Although pediatric primary care e-mails are analyzed in 1 of these stud-ies, analysis is combined with that of internal medi-cine e-mails.17 The majority of e-mails between a pediatrician and parent in our study were answered in 1 exchange between them. This is reassuring

be-cause of the concern that e-mail may lead to a con-tinuous dialogue of exchanges. In addition, most inquires focused on medical issues rather than ad-ministrative issues, which is in sharp contrast to telephone calls coming into a practice. E-mail was thought by parents to prevent both telephone calls and appointments, possibly indicating an impact on health care utilization.

Fig 1. Reasons for e-mail encounters (n⫽81).

Numerous national surveys of physicians and pa-tients have shown that although papa-tients favor e-mail communication with physicians, physicians are reluctant to oblige.17–19Reasons most often cited in-clude an increased workload, nonreimbursed time, and lack of security in Internet communication with patients. We found that the majority of parents en-dorse mail. However, despite their desire for e-mail access to physicians, nearly two thirds were unwilling to pay for the service. It was surprising that few were concerned with issues related to con-fidentiality.

The major content difference between the Poole and Glade analysis14of telephone content in pediat-ric practice and the results of our study is that, unlike telephone calls, the majority of e-mails concerned a health issue (89% of e-mails vs 15% of phone calls). The vast majority of e-mail encounters surrounded a single parent concern or request. In addition, a surprisingly large percentage of encounters were initiated to update the pediatrician, with a total of 36% providing information from the parent with no request for assistance from the pediatrician. These updates consisted primarily of new information re-garding the progression of a previously discussed medical problem or its response to therapy. Preexist-ing problems ranged from chronic illnesses such as asthma and food allergies to episodes of otitis media and thrush. This illustrates the benefits of e-mail in providing ongoing communication from the parent to the clinician. The IOM and other proponents have cited this as a possible benefit of e-mail.

Two other studies have examined the e-mail con-tent between providers and patients in primary care. A study done at Kaiser Permanente in Portland, Oregon, analyzed the e-mails of 5 primary care phy-sicians (3 internists and 2 pediatricians) and their patients over a 1-month period. Similar to our study, patients communicated directly with physicians. Re-sults were similar to ours: 77% of e-mails from pa-tients contained only 1 request, and the majority of inquiries concerned requests for specific medical in-formation (26% about medication and 22% about specific symptoms or diseases). However, 20% of the e-mails were regarding actions related to medica-tions such as requests for refills (our total was 11%).15

In a second study, White et al analyzed e-mail con-tent between 103 attending and resident physicians practicing in an academic medical center and their patients. Once again, the majority of these e-mails addressed a single issue (83%). There were large numbers of inquiries for medical updates (42%) and health questions (13%), although there were many more inquiries (57%) that did not require the re-sponse of a physician.16 Some of the differences found in these 2 studies may be due to the intrinsic difference between pediatric and internal medicine. Additionally, in the White et al study, patients were told that e-mails would be triaged to the appropriate personnel (nurses, administrative support personnel, physicians), whereas in our study, parents were aware that their e-mails would go directly to their pediatrician and thus did not include many requests that were directed at other office staff. This high-lights the impact that providing instructions to pa-tients about the use of e-mail may have on e-mail content.

The 2 physicians involved in this study exchanged e-mails directly with the parents of their patients. We have argued previously that physicians should re-frain from such exchanges and establish a central e-mail address so that incoming e-mails can be tri-aged similarly to telephone calls.3 This concept of e-mail triage may not be necessary. Unlike telephone calls, it seems that the vast majority of e-mails re-quire a physicians’ response. At least in this study, parents were aware of the “privilege” of direct con-tact with their physician and limited inquiries to those that pertained to the clinician. A few surveyed parents went so far as to state that pediatricians should not provide e-mail to their parents if parents were to abuse the privilege.

This study has a number of limitations. Only 2 pediatricians from a suburban private practice were involved in the study. Parents in this study were well-educated and had a high degree of experience with e-mail. How these results would generalize to other parents and pediatric practices is uncertain. Although there was no use of e-mail for an acute

TABLE 2. Demographic Characteristics of Subjects

n(%)

Marital status

Married or in lifetime partnership 44 (97.8)

Single 1 (2.2)

Parent’s education

Both parents with less than college degree 3 (5.6) One parent with college degree or higher 14 (26.0) Both parents with college degree or higher 37 (68.5) No. of children

1 13 (30.2)

2 23 (53.5)

ⱖ3 7 (16.3)

Response to questionnaire

E-mail 42 (77.8)

Fax 3 (5.6)

US mail 2 (3.7)

TABLE 3. E-mail Use of Study Participants

n(%)

Mother’s e-mail access

Work 17 (37.8)

Home 6 (13.33)

Both work and home 21 (46.7)

Work, home, and portable device 1 (2.2) Frequency of e-mail use

Daily or more frequently 41 (91.1)

Less than daily 4 (8.9)

E-mail encounters with pediatrician per month

1–3 33 (75.0)

3–5 8 (18.2)

5–7 1 (2.3)

⬎7 2 (4.5)

E-mail encounters with pediatrician per year

1–3 10 (22.2)

3–5 14 (31.1)

5–7 4 (8.9)

medical problem, such a situation remains a concern of many physicians. This lack of acuity may reflect the small sample size of this study.

This study represents an initial exploration of the use of e-mail in pediatric primary care. To date, studies regarding pediatric primary care e-mail cor-respondence have mostly been limited to descrip-tions of attitudes, knowledge, and behavior toward e-mail exchange but have not described actual e-mail content. Although Sittig15 did analyze e-mails be-tween pediatricians and parents, he also included the results of e-mail between internists and patients in the same analysis and thus was unable to tease out issues unique to primary care. Additional studies should be performed in a broad array of pediatric ambulatory care delivery systems, including both specialty and primary care. Particular attention should be paid to the use of e-mail to monitor and coordinate the care of patients with chronic condi-tions. Ultimately an experimental design will be nec-essary to assess the benefits of e-mail in pediatric practice.

The IOM has called for an increased use of nonvisit care in response to patients’ needs. E-mail may be the most efficient venue for the provision of such care.

In addition, e-mail documentation is a superior alternative to transcription of telephone care, ad-vancing the IOM’s goal of the elimination of most handwritten clinical data by the end of the decade. Through the facilitation of parent-physician commu-nication and provision of more efficient care, e-mail is an essential ingredient in the improvement of pe-diatric health care quality in the 21st century.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Financial support was provided by National Institute of Health grants 1 K24 HD 042489-01A2 and 2 T32 HP10014 10.

REFERENCES

1. Institute of Medicine. Crossing the Quality Chasm. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001

2. Delbanco T, Sands DZ. Electrons in flight— e-mail between doctors and patients.N Engl J Med.2004;350:1705–1707

3. Bauchner H, Adams W, Burstin H. “You’ve got mail”: issues in com-municating with patients and their families by e-mail.Pediatrics.2002; 109:954 –956

4. Mandl KD, Kohane IS, Brandt AM. Electronic patient-physician communication: problems and promise. Ann Intern Med. 1998;129: 495–500

5. Moyer CA, Stern DT, Dobias KS, Cox DT, Katz SJ. Bridging the elec-tronic divide: patient and provider perspectives on e-mail communica-tion in primary care.Am J Manag Care.2002;8:427– 433

6. Borowitz SM, Wyatt JC. The origin, content, and workload of e-mail consultations.JAMA.1998;280:1321–1324

7. Kassirer JP. The next transformation in the delivery of health care.

N Engl J Med.1995;332:52–54

8. Berry LL, Seiders K, Wilder SS. Innovations in access to care: a patient-centered approach.Ann Intern Med.2003;139:568 –574

9. Sittig DF, King S, Hazlehurst BL. A survey of patient-provider e-mail communication: what do patients think?Int J Med Inform.2001;61:71– 80 10. DeVille K, Fitzpatrick J. Ready or not, here it comes: the legal, ethical, and clinical implications of e-mail communications.Semin Pediatr Surg.

2000;9:24 –34

11. Katz SJ, Moyer CA, Cox DT, Stern DT. Effect of a triage-based e-mail system on clinic resource use and patient and physician satisfaction in primary care: a randomized controlled trial.J Gen Intern Med.2003;18: 736 –744

12. Baker L, Wagner TH, Singer S, Bundorf MK. Use of the Internet and e-mail for health care information: results from a national survey.

JAMA.2003;289:2400 – 406

13. Spielberg AR. On call and online: sociohistorical, legal, and ethical implications of e-mail for the patient-physician relationship.JAMA.

1998;280:1353–1359 TABLE 4. Parents Attitudes Toward E-mailing Their Child’s Pediatrician

n(%)

Parent satisfaction with e-mailing pediatrician

Great 34 (75.6)

Very good 10 (22.2)

Fair 1 (2.2)

E-mail prevents telephone calls (as viewed by parent) 1 (2.2)

Usually 26 (57.8)

Most of the time 13 (28.9)

Sometimes 6 (13.3)

E-mail prevents appointments (as viewed by parent) 6 (13.3)

Usually 12 (27.9)

Most of the time 11 (25.6)

Sometimes 14 (32.6)

Not usually 6 (14.0)

All pediatricians should provide e-mail access to parents of their patients

Yes 35 (79.6)

No 5 (11.4)

Unsure 4 (9.1)

More likely to choose a pediatrician who provides e-mail access

Yes 28 (65.1)

No 9 (20.9)

Unsure 7 (16.3)

Concerned with e-mail confidentiality

Greatly concerned 4 (9.8)

Very concerned 3 (7.2)

Somewhat concerned 15 (36.6)

Not at all concerned 19 (46.3)

Price respondent is willing to pay per e-mail encounter with physician

Not willing 26 (63.4)

$5 6 (14.6)

$10 4 (9.8)

$15 1 (2.4)

14. Poole SR, Glade G. Cost-efficient telephone care during pediatric office hours.Pediatr Ann.2001;30:256 –267

15. Sittig DF. Results of a content analysis of electronic messages (email) sent between patients and their physicians.BMC Med Inform Decis Mak.

2003;3:11

16. White CB, Moyer CA, Stern DT, Katz SJ. A content analysis of e-mail communication between patients and their providers: patients get the message.J Am Med Inform Assoc.2004;11:260 –267

17. Kleiner KD, Akers R, Burke BL, Werner EJ. Parent and physician attitudes regarding electronic communication in pediatric practices.

Pediatrics.2002;109:740 –744

18. Hobbs J, Wald J, Jagannath YS, et al. Opportunities to enhance patient and physician e-mail contact.Int J Med Inform.2003;70:1–9

19. Harris Interactive. Patient/physician online communication: many pa-tients want it, would pay for it, and it would influence their choice of doctors and health plans.Health Care News.2002;2:1–13

NEW RULES MAY DAMAGE NIH

“The Taxpayer-Funded National Institutes of Health has long been a magnet for some of the world’s top scientists, drawn to its state-of-the-art laboratories, intel-lectual freedom, high-powered peers and good pay.

Now the federal government wants to treat these government employees more like, well, government employees. That is causing an uproar at the NIH, with some senior scientists predicting long-term damage to the organization’s recruiting and employee-retention goals.

The griping stems from stringent new ethics rules announced last month by NIH director Elias Zerhouni to combat complaints from Congress and watchdog groups that some NIH scientists had lucrative outside activities that might be conflicts of interest. The new rules ban all 18,000 NIH staffers from consulting for the drug industry and other biomedical-related organizations. Dr. Zerhouni also announced that about 6,000 NIH employees would be barred from holding stock in pharma-ceutical or biotechnology companies and must sell their current holdings. The rules restrict holdings of drug or biotech stocks by other NIH employees and sharply curtail honoraria. . . . The new rules have also angered NIH lifers on a deeper level: Their pride is hurt. Internal NIH scientists—who have included five Nobel Lau-reates—tend to want to be treated more like academic rock stars, not as function-aries in the bowels of the federal work force. To many of them, the new rules reek of diminished status.

Even worse, the rules, which go further than previous restrictions imposed over the past few years, give many scientists the feeling that they aren’t trusted. One rule: a ceiling of $200 on honoraria. The implication ’is that I can be bought for $200,’ says Edward Korn, chief of the laboratory of cell biology at the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute and 50-year NIH veteran. ’Many of us think it’s a personal insult.’ Like many colleagues, Dr. Korn says he believes in tough ethics rules, but thinks the new ones ’overreach.’ . . . Scientists also complain of a steady increase in what they call petty rules and bureaucratic procedures.”

Wysocki B Jr.Wall Street Journal.March 3, 2005

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2004-1297

2005;115;1283

Pediatrics

Bauchner

Shikha G. Anand, Mitchell J. Feldman, David S. Geller, Alice Bisbee and Howard

and Parents

A Content Analysis of E-mail Communication Between Primary Care Providers

Services

Updated Information &

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/115/5/1283

including high resolution figures, can be found at:

References

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/115/5/1283#BIBL

This article cites 18 articles, 2 of which you can access for free at:

Subspecialty Collections

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/professionalism_sub

Professionalism

_management_sub

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/administration:practice

Administration/Practice Management following collection(s):

This article, along with others on similar topics, appears in the

Permissions & Licensing

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/Permissions.xhtml

in its entirety can be found online at:

Information about reproducing this article in parts (figures, tables) or

Reprints

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/reprints.xhtml

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2004-1297

2005;115;1283

Pediatrics

Bauchner

Shikha G. Anand, Mitchell J. Feldman, David S. Geller, Alice Bisbee and Howard

and Parents

A Content Analysis of E-mail Communication Between Primary Care Providers

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/115/5/1283

located on the World Wide Web at:

The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is

by the American Academy of Pediatrics. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 1073-0397.