Pain Experience of Children With Headache and Their Families:

A Controlled Study

Minna Aromaa, MD*‡; Matti Sillanpa¨a¨, MD, PhD*; Pa¨ivi Rautava, MD, PhD‡; and Hans Helenius, MSc§

ABSTRACT. Objective. This study reports the pain sensitivity of children with headache and their family members, as well as the prevalence of recurring aches, psychosocial life, and family environment of children with headache at preschool age.

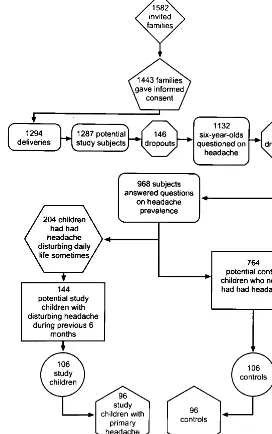

Design. A representative population-based sample of 1443 families expecting their first child were followed over 7 years. A screening questionnaire relating to the child’s headache was sent to parents of a representative sample of 1132 6-year-old children. Of 144 children suf-fering from headache, 106 (76%) were examined and in-terviewed clinically. Ninety-six children with primary headache (58 migraine and 38 tension-type headache children) and matched controls (nⴝ96) were included in further examinations.

Results. Children with headache were more often ex-tremely sensitive to pain according to their parents, were more excited about physical examinations, cried more often during blood sampling or vaccination, avoided play or games more often because they were afraid of hurting themselves, and had recurring abdominal and growing pains more often than did control children. The fathers of children with headache were more often ex-tremely sensitive to pain. Children with headache re-acted with somatic symptoms, usually with pain and functional intestinal disorders in stress situations, felt more tired, and had more ideations of death during the previous month. They had also had more problems in day care and fewer hobbies such as scout or club meet-ings than did control children.

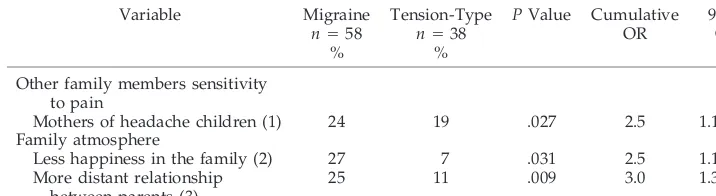

More mothers of tension-type headache children than those of migraine children reported that they were con-siderably sensitive to pain. Tension-type headache chil-dren also had a poorer family environment; the family atmosphere was more often unhappy and the relation-ship between the parents was more often distant than in the families of children with migraines.

Conclusions. In addition to somatic factors, it is impor-tant to consider the child’s pain sensitivity, reaction to var-ious stress situations, and family functioning when study-ing childhood headache. The child’s copstudy-ing mechanisms can be supported by information given by the parents. School entry can be considered a suitable period for careful investigation into possible occurrence of headache and also for giving information about headache and its management.Pediatrics 2000;106:270 –275;headache, child, pain, sensitivity, family.

ABBREVIATIONS. OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; RAP, recurrent abdominal syndrome.

H

eadache is one of the leading chronic condi-tions bothering children.1 Headache, espe-cially migraine, is clearly a familial phenom-enon.2– 4 Psychological components also play a significant role in childhood headache.5,6In addition to genetic and psychological components, a compo-nent of social learning of pain seems to occur in the family. Regardless of the age of the child, the family is central to a child’s life. Family factors are assumed to be involved in the pain experiences of children, because most of the health problems are first dealt within the family. Family model theories of different categories of pain have been proposed.7 The terms sympathetic pain and complaint modeling are some-times used.8The pain of the child may even affect the functioning of the whole family.In the present study, the emphasis was on child-hood headache from the family viewpoint. We inves-tigated the pain experiences of headache children and their family members and the occurrence of other recurrent aches, psychosocial life, and family environment before the child’s school entry.

METHODS

The present study is part of the Finnish Family Competence Study. Subject collection was started in 1986 in the province of Turku and Pori, southwestern Finland, based on stratified, ran-domized cluster sampling. Each cluster consisted of the popula-tion of a health authority area. The mean populapopula-tion density of the municipalities of the sample did not differ significantly from that of all municipalities in the province.9Randomization (drawing by lot) was conducted by selecting 11 of the 35 health authority areas in the province. All public maternity health care clinics (n⫽67) and well-baby clinics (n⫽ 72) of the 11 health authority areas participated in the study. The original study sample consisted of nulliparous women and their spouses starting to expect their first infant and paying their first visit to a maternity health care clinic in 1986. Fig 1 shows the creation of study and control cohorts. Invitations to participate in the study were sent to 1582 families, of which 1443 (91%) accepted the invitation and gave their informed consent. There were 1294 deliveries: 3 of the children died in labor, 8 children died in infancy, 5 children moved abroad, and 146 families dropped out or were lost to the study over the 7 years of follow-up. Thus, the final number of subjects was 1132.

The families were followed up during pregnancy and after the birth of the child until the child was 6 years old. At that age, the parents were asked 2 questions: 1) “Has your child had headache disturbing daily activities in the preceding 6 months?” and 2) “Has your child had headache disturbing daily activities during some period of his/her life (before the last 6 months)?” Nine hundred sixty-eight parents (86%) answered the questions of prevalence. A total of 204 of the 968 children (22%) had previously had headache disturbing their daily activities. Of the 204, 144 From the Departments of *Child Neurology, ‡Public Health, and

§Biosta-tistics, University of Turku, Finland.

Received for publication Dec 6, 1999; accepted Dec 6, 1999.

Address correspondence to Minna Aromaa, MD, Department of Public Health, University of Turku, Lemminka¨isenkatu 1, 20520 Turku, Finland. E-mail: minna.aromaa@tyks.fi

children (71% of headache children and 15% of all children) had suffered from disturbing headache during the preceding 6 months. Children with present headache and control children were invited to Turku University Hospital, Department of Child Neurology, to participate in a clinical pediatric and neurological headache examination conducted by the first author. A suggestion was made that the children should be accompanied by at least 1 parent. Of the 144 children, 106 (74%) with present headache and matched control children participated in the study. The control children were matched for age, sex, and the degree of urbanization of their domicile. After the clinical examination, the classification of different headache types could be conducted. The Classification of International Headache Society10was used. The prevalence of migraine among study subjects was 55% (58/106) and that of tension-type headache was 36% (38/106) of all present headaches. Children with secondary headaches were excluded from subse-quent examinations. Thus, the total number of participants was 96 children suffering from primary headache during the preceding 6 months (later referred to as present headache) and 96 matched controls (Fig 1). The sex distribution of children with present headache was nearly equal (51% boys and 49% girls). Of the children, 56% lived in urban areas, 23% in suburban areas, and 21% in rural areas. The corresponding proportions of all 0- to 14-year-old children living in southwestern Finland are 54% for urban, 17% for suburban, and 29% for rural areas (unpublished data). The average age of the children at the time of examination was 7.0 years old. Ninety-two percent of headache children were

accompanied by the mother (84% of control children), whereas 8% (16% of control children) came with the father.

Pain Sensitivity in Children With Headache and Control Children

Children and parents were asked to estimate whether the child was sensitive to pain, afraid to see a doctor, excited about the clinical examination, and easily crying during blood sampling or vaccination. Questions were asked about any avoidance reactions during play or games for fear of getting hurt and about the occurrence of other recurring ache (stomachache, growing pain, other pain in extremities, toothache, and backaches). The intensity of headache pain and stomachache was assessed using a 10-cm visual analog scale11(0 cm⫽no pain, 10 cm⫽intolerable pain). One or both parents helped the child with this assessment.

Pain Sensitivity in Family Members of Children With Headache and Control Children

Questions were asked about the pain sensitivity of the mother (including questions about menstrual pain and the mother’s as-sessment of her labor pains), the father, and siblings. A question was asked about the reaction of the parents to the child’s pain.

Upbringing of Child

The parents were asked whether they tend to forbid the child to participate in play or games because the child might get hurt and

what typical ways they had of comforting the child in pain. Questions were also asked about the frequency of agreement between parents on the upbringing of the child and about the reactions of the parents to the child’s temper tantrums.

The Family Environment of Children With Headache and Control Children

Questions were asked about how the family reacted to conflicts within the family. Questions were also asked about family rela-tionships as they appeared in matters such as jealousy, quarreling, and indifference among siblings and between parents. The par-ent/parents were asked to assess the degree of happiness of the family and the relationship between parents. The family’s finan-cial situation and possible unemployment of either parent were also assessed in this way.

The Psychosocial Life of Children With Headache and Control Children

The child’s coping mechanisms in stress situations and depres-sive symptoms12were assessed. Questions were asked about any friends, regular hobbies, and the number of daily hours of TV-watching. The families were asked to describe the type of the child’s day care system, to give the number of times that the child had changed day care centers, to tell whether they were satisfied with the child’s day care system, to report whether the child had had any problems there, and to state the child’s opinion about day care. The regularity of meals, regularity of home-cooked meals, as well as sleeping habits and time of going to bed and hours of sleep were analyzed. A question was asked about the number of hours that the child spent outside the home in fresh air.

Comparison Between Migraine Children and Tension-Type Headache Children

Migraine children and tension-type headache children were compared in all above variables.

Statistical Methods

Descriptive analyses of differences in the distribution of vari-ables between children with present headache and control chil-dren were studied by cross-tabulation. Because of the matched case– control design of data, the statistically significant tests of differences in these comparisons were performed applying condi-tional logistic regression analysis.13Differences were quantified

calculating odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The statistical comparisons of migraine and tension-type headache groups within the children with present headache were performed using ordinary logistic models for binary responses and with cumulative logistic models for polytochomous ordinal scaled re-sponses.14APvalue⬍.05 was interpreted as statistically signifi-cant. BMDP90 statistical software was used for statistical compu-tation.15

RESULTS

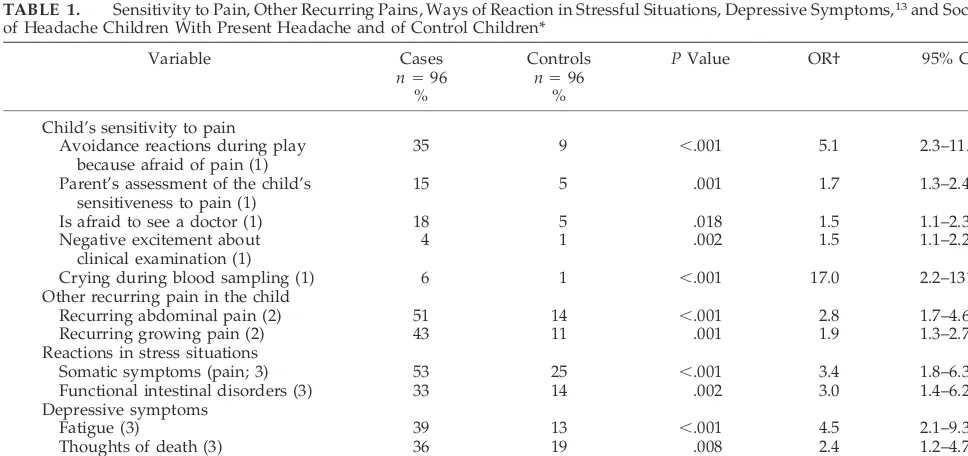

The parents of children with headache assessed their child as extremely sensitive to pain more often than did the parents of control children. Headache children were more often excited about the clinical examination and cried more often during blood sam-pling or vaccination. They also avoided play or games more often for fear of getting hurt. Headache children had more recurring stomach and growing pains than did control children (Table 1; Fig 2).

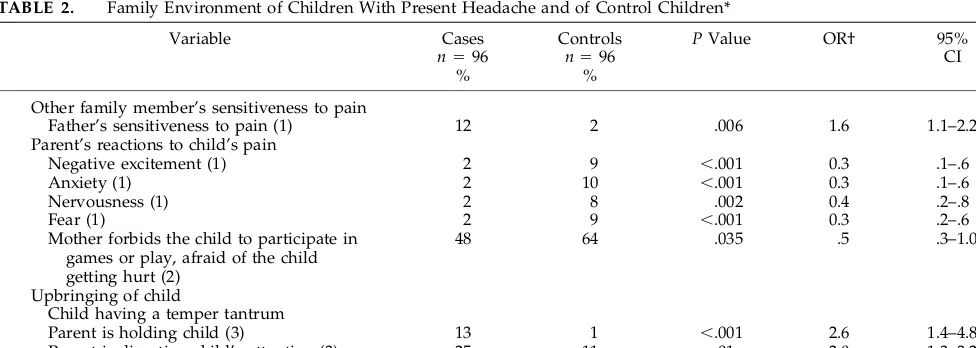

The fathers of headache children were more sen-sitive to pain than were those of control children (Table 2).

When the child complained of pain, the parents of control children talked to them to comfort them more often than did the parents of headache children. They also felt anxious, frightened, excited, and ner-vous in the presence of the child’s pain more often than did the parents of headache children. The moth-ers of control children also forbade their child to participate in play or games more often because they were afraid that the child might get hurt. When the child had a temper tantrum, the parents of headache children tried to hold the child or to divert the child’s attention (Table 2).

Conflicts in the family led to open quarreling (P⫽

.003; OR: 2.3; 95% CI: 1.2– 4.4) and sulking (P⫽.017; OR: 7.3; 95% CI: 1.4 –35.4) in the families of headache children more often than in control families.

Chil-TABLE 1. Sensitivity to Pain, Other Recurring Pains, Ways of Reaction in Stressful Situations, Depressive Symptoms,13and Social Life of Headache Children With Present Headache and of Control Children*

Variable Cases

n⫽96 %

Controls

n⫽96 %

PValue OR† 95% CI

Child’s sensitivity to pain Avoidance reactions during play

because afraid of pain (1)

35 9 ⬍.001 5.1 2.3–11.6

Parent’s assessment of the child’s sensitiveness to pain (1)

15 5 .001 1.7 1.3–2.4

Is afraid to see a doctor (1) 18 5 .018 1.5 1.1–2.3

Negative excitement about clinical examination (1)

4 1 .002 1.5 1.1–2.2

Crying during blood sampling (1) 6 1 ⬍.001 17.0 2.2–131

Other recurring pain in the child

Recurring abdominal pain (2) 51 14 ⬍.001 2.8 1.7–4.6

Recurring growing pain (2) 43 11 .001 1.9 1.3–2.7

Reactions in stress situations

Somatic symptoms (pain; 3) 53 25 ⬍.001 3.4 1.8–6.3

Functional intestinal disorders (3) 33 14 .002 3.0 1.4–6.2

Depressive symptoms

Fatigue (3) 39 13 ⬍.001 4.5 2.1–9.3

Thoughts of death (3) 36 19 .008 2.4 1.2–4.7

Social life of the child

Scout or club meetings (3) 29 48 .018 .4 .2–.9

Problems in day care (3) 32 18 .028 2.1 1.1–4.2

* %⫽percentage of answers of: 1) markedly on the scale: no, slightly, moderately, or markedly; 2) at least once a month on the scale: at least once a month, rarely or hardly ever; 3) yes on the scale: yes or no.

dren with headache reacted with somatic symptoms (usually with pain) and with functional intestinal disorders (diarrhea or constipation) to stress situa-tions more often than did control children. In the depression part ofDiagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, III-Revised12they reported that they had felt tired and had had thoughts of death during the previous month more often than did control chil-dren. They had also had more problems in the day care center than had control children. Headache chil-dren watched television for more hours daily (P ⫽

.021; the mean among headache children was 1.5 hours and among controls was 1.3 hours daily). Con-trol children had social hobbies such as scout or club meetings more often than did children with head-ache (Table 2).

Characteristics of Migraine Children and Tension-Type Headache Children

When migraine children were compared with ten-sion-type headache children the following differ-ences were found: headache pain was significantly more intensive among migraine children (on the

vi-sual analog scale,11 migraine showed a mean of 5.8 cm and tension-type headache showed a mean of 4.6 cm;P⫽.001). The mothers of tension-type headache children were more often extremely sensitive to pain than were mothers of migraine children. The families of tension-type headache children had a worse atmo-sphere. The families felt unhappy and the relation-ship between parents was distant more often in the families of children with tension-type headache (Ta-ble 3).

DISCUSSION

The present study was based on a prospective follow-up of a highly representative sample from an unselected population. The participation rates throughout the follow-up were satisfactory. The fam-ilies of the study children and of the control children did not benefit financially from participation in the study. The basic data of the parents and their chil-dren were collected during the follow-up, with blinded case or control status of the study sub-jects.16 –18 However when the child was 6 years old, classification into cases and controls was conducted

Fig 2. Problems associated with childhood headache.

TABLE 2. Family Environment of Children With Present Headache and of Control Children*

Variable Cases

n⫽96 %

Controls

n⫽96 %

PValue OR† 95%

CI

Other family member’s sensitiveness to pain

Father’s sensitiveness to pain (1) 12 2 .006 1.6 1.1–2.2

Parent’s reactions to child’s pain

Negative excitement (1) 2 9 ⬍.001 0.3 .1–.6

Anxiety (1) 2 10 ⬍.001 0.3 .1–.6

Nervousness (1) 2 8 .002 0.4 .2–.8

Fear (1) 2 9 ⬍.001 0.3 .2–.6

Mother forbids the child to participate in games or play, afraid of the child getting hurt (2)

48 64 .035 .5 .3–1.0

Upbringing of child

Child having a temper tantrum

Parent is holding child (3) 13 1 ⬍.001 2.6 1.4–4.8

Parent is diverting child’s attention (3) 25 11 .01 2.0 1.3–3.2

Parent is directing in a strong voice (3) 48 62 .033 .6 .3–.9

* %⫽percentage of answers of: 1) markedly on the scale: no, slightly, moderately, or markedly; 2) yes on the scale: yes or no; 3) nearly always on the scale: never, nearly always, or always.

based on a question about the occurrence of head-ache. The first author personally invited all children with headache, the controls, and their parents to participate in a clinical examination and interviewed and examined the children (cases and controls). However, questions about the characteristics of headache could naturally only be asked of the head-ache children. Therefore, the author was not blinded to the case– control status, which may limit the gen-eralizability of the results of the study. In contrast, any bias may be decreased by the fact that both case and control subjects were studied and interviewed by the same person in the same manner.

An increased general pain sensitivity proved to characterize children with headache and their par-ents. Similarly, children with headache were more psychosomatically reactive to various short-term and long-term stress situations than were control chil-dren. The atmosphere of the families of tension-type headache children was poorer than the atmosphere of families of migraine children.

In the study by Violin and Giurgea,19chronic adult pain patients had significantly more pain patients in their families. Thus, patients with other family mem-bers suffering from pain may be more sensitive to pain and/or have a greater tendency toward pain behavior themselves. This result was in agreement with the present study. Although the heredity of headache was more often maternal in our study pop-ulation, the fathers were reported to be more sensi-tive to pain. This information may be slightly biased because the mothers usually gave it, because the mother accompanied most of the children to the clinical examination. In contrast, the mothers of ten-sion-type headache children reported that they were sensitive to pain more often than did the mothers of migraine children.

Headache children also seemed to be more cau-tious in play and hobbies, because they were afraid of getting hurt. The parents were aware of this and did not try to forbid the child to participate in play or games. In contrast, the parents of control children were more worried about the child’s pain than were the parents of headache children. The result is ana-logical with and understandable based on the study by Wood et al20 on ⬃40 families with Crohn’s dis-ease, ulcerative colitis, and functional recurrent ab-dominal syndrome (RAP), finding that RAP families

display less overprotection than do Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis families. The authors suggested that this represents a family configuration of en-meshment rigidity, poor conflict resolution, and little protection. Thus, the absence of organic pathology seems to be associated with less protection of the sick child, although the overt symptoms can be as intense and severe in RAP as in organic diseases. Perhaps the lack of pathophysiology allowed the families to view the child as not really sick, thus permitting or even encouraging this kind of family configuration.

In addition to headache pain, other recurring aches occurred in headache children. Headache is some-times a component of periodic syndromes, which commonly include vomiting, abdominal pain, and vertigo in addition to headache.21Children with current abdominal pain often suffer often from re-curring headaches.22

In the present study, headache children reported more tiredness and more thoughts of death during the previous month. Gauvain-Piquard et al23 found in their study of 2- to 6-year-old children with cancer pain that depression-like items were so close to pain items, in terms of their contributions and correla-tions, that they can be considered secondary or gen-eral signs of pain. Although headache is not as dan-gerous as cancer, very severe recurrent headache pain can cause depressive symptoms in young chil-dren.

Because the application of self-reported rating scales is limited to children who can understand the objectives and descriptors of these techniques, the child and his/her parent were asked to mark the intensity of headache pain on the visual analog scale together, in other words, the parent helped the child. Migraine was more intensive according to the results obtained with this scale. This result is in agreement with an earlier Finnish study.24

Headache in children can be an indicator of prob-lems in the life of the child or family. Family mem-bers usually teach each other to respond to painful experiences. If parents often express their pain ver-bally or nonverver-bally, overreact to pain or are anxious or depressed about pain, the child is probably more prone to learning noncoping pain behavior. Al-though migraine has a strong hereditary component, the child’s pain-coping mechanisms can be influ-enced by information given by the parents. Head-TABLE 3. Comparison Between Children With Migraine and Those With Tension-Type

Head-ache*

Variable Migraine

n⫽58 %

Tension-Type

n⫽38 %

PValue Cumulative OR

95% CI

Other family members sensitivity to pain

Mothers of headache children (1) 24 19 .027 2.5 1.1–5.5

Family atmosphere

Less happiness in the family (2) 27 7 .031 2.5 1.1–5.9

More distant relationship between parents (3)

25 11 .009 3.0 1.3–7.1

ache can have many social and psychological conse-quences in the life of a child and family. Therefore, school entry can be considered a suitable time for careful investigation into childhood headache and also a time when information about headache and ways of coping with it can be appropriately dissem-inated.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by the Arvo and Lea Ylppo¨ Foundation.

We thank Simo Merne, MA, for revising the language of this report; Inger Vaihinen for technical assistance; and Olli Kaleva, BSc, for skillful computation of the statistical analysis.

REFERENCES

1. Newacheck PW, Taylor WR. Childhood chronic illness: prevalence, severity and impact.Am J Public Health. 1992;82:364 –371

2. Vahlquist B. Migraine in children.Int Arch Allergy. 1955;7:348 –355 3. Bille B. A 40-year follow-up of schoolchildren with migraine.

Cephalal-gia. 1997;17:488 – 491

4. Mortimer MJ, Kay J, Jaron A, Good PA. Does a history of maternal migraine or depression predispose children to headache and stomach-ache?Headache. 1992;32:353–355

5. Cooper PJ, Bawden HN, Camfield PR, Camfield CS. Anxiety and life events in childhood migraine.Pediatrics. 1987;79:999 –1004

6. Holden EW, Gladstein J, Trulsen M, Wall B. Chronic daily headache in children and adolescents.Headache. 1994;34:508 –514

7. Minuchin S, Baker L, Rosman BL, Liebman R, Milman L, Todd TC. A conceptual model of psychosomatic illness in children.Arch Gen Psy-chiatry. 1975;32:1031–1038

8. Schechter NL. Recurrent pains of children: on overview and an ap-proach.Pediatr Clin North Am. 1984;31:949 –968

9. Rautava P, Sillanpa¨a¨ M. The Finnish Family Competence Study: knowl-edge of childbirth of nulliparous women seen at maternity health care clinics.J Epidemiol Commun Health. 1989;43:253–260

10. International Headache Society. Classification and diagnostic criteria

for headache disorders, cranial neuralgias and facial pain.Cephalalgia. 1988;(suppl 7)8:

11. Price DD, McGrath PA, Rafii A, Buckingham B. The validation of visual analogue scales as ratio scale measures for chronic and experimental pain.Pain. 1983;17:45–56

12. American Psychiatric Association.Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-Revised, III. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1987

13. Breslow NE, Day NE.Statistical Methods in Cancer Research: The Analysis of Case-Control Studies, I. Lyon, France: International Agency of Cancer; 1980

14. Agresti A.Categorical Data Analysis. New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons; 1990

15. Dixon WJ, Brown MB, Engelman L, Jennrich RI.BMDP Statistical Soft-ware Manual, III. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 1990 16. Aromaa M, Sillanpa¨a¨ M, Rautava P, Helenius H. Prevalence of frequent

headache in young Finnish adults starting a family.Cephalalgia. 1993; 13:330 –337

17. Aromaa M, Rautava P, Sillanpa¨a¨ M, Helenius H. Prepregnancy head-ache and the well-being of newborn.Headache. 1996;36:409 – 415 18. Aromaa M, Rautava P, Sillanpa¨a¨ M, Helenius H. Factors of early life as

predictors of headache in children at school entry.Headache. 1998;38: 23–30

19. Violin A, Giurgea D. Familial models for chronic pain.Pain. 1984;18: 199 –203

20. Wood B, Watkins JB, Boyle JT, Nogueira J, Zimand E, Carroll L. The psychosomatic family model: an empirical and theoretical analysis.Fam Process. 1989;28:399 – 417

21. Lanzi G, Balottin U, Cernibori A.Headache in Children and Adolescents. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier Science Publishers; 1989:33–37 22. Alfven G. Preliminary findings on increased muscle tension and

ten-derness, and recurrent abdominal pain in children: a clinical study.Acta Paediatr. 1993;82:400 – 403

23. Gauvain-Piquard A, Rodary C, Rezvani A, Lemerle J. Pain in children aged 2– 6 years: a new observational rating scale elaborated in a pedi-atric oncology unit—preliminary report.Pain. 1987;31:177–188 24. Ha¨ma¨la¨inen ML.Optimal Drug Treatment of Recurrent Headaches and

Migraine in Children—Clinical and Pharmacological Study. Helsinki, Finland: University of Helsinki; 1997. Doctoral thesis

THREE CHEERS FOR BARNEY

In a coverage situation, I was called to the hospital to see a rapidly worsening child with respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and bronchiolitis. He was a former preemie who had had Synergis. At 1 year, he weighed 40 pounds. He was extremely agitated, cyanotic, and resisting treatment. Popping the “Barney Tape” into the VCR, allowed him to sit on father’s lap, a man of some girth. Absorbed by “Barney,” the infant relaxed, allowing oxygen and albuterol while awaiting trans-fer. It was as if there were 3 Barneys; the purple one, the slightly purple one, and the pink one. Thank heaven for Barney!

DOI: 10.1542/peds.106.2.270

2000;106;270

Pediatrics

Minna Aromaa, Matti Sillanpää, Päivi Rautava and Hans Helenius

Study

Pain Experience of Children With Headache and Their Families: A Controlled

Services

Updated Information &

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/106/2/270

including high resolution figures, can be found at:

References

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/106/2/270#BIBL

This article cites 17 articles, 2 of which you can access for free at:

Subspecialty Collections

icine_sub

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/adolescent_health:med

Adolescent Health/Medicine

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/washington_report

Washington Report

following collection(s):

This article, along with others on similar topics, appears in the

Permissions & Licensing

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/Permissions.xhtml

in its entirety can be found online at:

Information about reproducing this article in parts (figures, tables) or

Reprints

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/reprints.xhtml

DOI: 10.1542/peds.106.2.270

2000;106;270

Pediatrics

Minna Aromaa, Matti Sillanpää, Päivi Rautava and Hans Helenius

Study

Pain Experience of Children With Headache and Their Families: A Controlled

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/106/2/270

located on the World Wide Web at:

The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is

by the American Academy of Pediatrics. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 1073-0397.