Fear of Obesity

Among

Adolescent

Girls

Nancy

Moses,

MNS,

RD, Mansour-Max

Banilivy,

PhD,

and

Fima

Lifshitz,

MD

From the Department of Pediatrics and Department of Child Psychiatry, North Shore University Hospital, Manhasset, New York, and the Departments of Pediatrics and of Psychiatry, Cornell University Medical College, New York

ABSTRACT. The perceptions concerning weight, dieting practices, and nutrition of 326 adolescent girls attending an upper middle-class parochial high school were studied in relation to their body weight. Underweight or over-weight students were those with greater than 10% body weight differential for height. The high school students reported an exaggerated concern with obesity regardless of their body weight or nutrition knowledge. Under-weight, normal weight, and overweight girls were dieting to lose weight and reported frequent self-weighing prac-tices. As many as 51% (n = 60) of the underweight

adolescents described themselves as extremely fearful of being overweight and 36% (n = 43) were preoccupied

with body fat. A distorted perception of ideal body weight was documented, particularly among the underweight students; the greater the underestimation of perceived ideal body weight, the greater the actual deficit in ideal body weight for height ofthe students (r = .73; P < .001). Normal weight and overweight girls had better concord-ance between their actual and perceived ideal body weight for height. The frequency of bingeing and vomiting be-haviors was similar among the three weight categories. The data suggest that fear of obesity and inappropriate eating behaviors are pervasive among adolescent girls regardless of body weight or nutrition knowledge.

Pedi-atrics 1989;83:393-398; eating disorder, adolescent, body

weight, nutrition knowledge, malnutrition.

Inappropriate eating behaviors and attitudes have often been recognized among the adolescent population. Dissatisfaction with body weight and appearance and unhealthy approaches toward weight reduction such as fad diets are commonly reported among our youth.13 In a recent study, 13% of tenth-grade students reported performing various types of purging behavior such as

self-Received for publication Nov 3, 1987; accepted March 29, 1988. Reprint requests to (F.L.) Department of Pediatrics, North Shore University Hospital, Manhasset, NY 11030.

PEDIATRICS (ISSN 0031 4005). Copyright © 1989 by the American Academy of Pediatrics.

induced vomiting and use of laxatives and diuret-ics.4 These maladaptive behaviors seem to be oc-curring in younger adolescents than was previously reported.57 Additionally, a variety of eating disor-ders have also been described during adolescence that result in poor growth and delayed sexual de-velopment.’2 One such syndrome, fear of obesity, was defined as self-induced malnutrition due to an exaggerated concern about becoming fat. The fear of obesity was not associated with overt psycho-pathology and was, therefore, considered to be dis-tinctly different from anorexia nervosa.’2

The reason for the apparent high prevalence of inappropriate eating behaviors and eating dis-orders among adolescents remains unclear. The social and cultural ideal of thinness has often been

blamed,’3’7 and perhaps it is this influence that has resulted in a fertile environment for the devel-opment of eating disorders and, in extreme cases, anorexia nervosa and bulimia. Lack of nutrition knowledge and misinformation regarding appropri-ate nutrition has also received attention as a con-tributing factor in the etiology of eating disor-ders.4’18”9 A positive influence of a nutrition edu-cation program on the dietary intakes of sixth- and seventh-grade students has been described,#{176} and

greater nutrition knowledge among 12- to 14-year-old girls has been related to good eating practices.2’ Other investigations have not shown this associa-tion between adolescents’ nutrition and health knowledge, and their behaviors, however.22’23

SO.

50

40

30

20

10

METHODS

The subjects of this study were 326 adolescent girls (13 to 18 years of age) who were attending an all girls Catholic parochial high school located in

an upper middle-class suburban area of Long Is-land, New York. Written permission to perform

this study was obtained by the high school admin-istrators and by the hospital research and publica-tion committee.

The questionnaire was precoded to preserve

con-fidentiality and was administered to 326 high school students during a 45-minute homeroom period. Standardized oral instructions for the test instru-ments were provided by the classroom teachers. In the questionnaire, students’ perceptions of their present weight and their ideal body weight for

height, frequency of self-weighing, and dieting prac-tices were evaluated. Those who were dieting were asked to define their dieting habits in one of four

categories; these included dieting to lose weight, dieting to gain weight, dieting to maintain weight, and dieting for specific medical purposes. The time

of dieting was also specified as either ongoing at the time of the survey and/or having taken place in the recent past. Additionally, in the question-naire the presence of disturbed eating behaviors and attitudes were explored, including extreme anx-iety concerning being overweight, preoccupation with body fat, uncontrollable eating binges, impulse

to vomit after meals, and vomiting behavior. The adolescents’ nutrition knowledge also was ascer-tamed by a multiple choice questionnaire pretested for content accuracy with a Kuder Richardson-20 reliability coefficient of .80 as described by Byrd-Bredbenner.24

Height and weight measurements were collected at the high school by the investigators within 2 weeks after the administration of the questionnaire. The students wore school uniforms and were weighed without shoes on a standard balance beam scale. Students were measured for height without shoes by means of a square level against a wall with a tape measure. The measurements were compared with growth standards established by the National Center for Health Statistics for age and sex.25 For each student, the percentage of ideal body weight for height at the 50th percentile was calculated and three weight categories were defined: (1) under-weight-<90% of ideal weight for height, (2) nor-ma! weight-90% to 110% of ideal body weight for

height, and (3) overweight->110% of ideal body weight for height. Further evaluation regarding the students’ degree of weight deficits or excesses were

also determined based on deviations from normal ideal body weight for height.

The

x2

test of independence was computed tocompare the frequency of dieting behavior, self-weighing, bingeing, vomiting, and inappropriate at-titudes regarding body weight among the three weight categories. Regression and correlation

analysis was used to study the relationship between the students’ perceptions of their ideal body weight and their actual body weights. According to the Goodness of Fit test, the criteria for normality were not met on the distribution of nutrition knowledge

test scores. Therefore, nonparametric statistics, in-cluding Kruskal-Wallis one-factor analysis of var-iance by ranks and the Mann-Whitney U test (rank sum test),26 were used for comparison of these test scores with body weight categories and eating be-haviors and attitudes.

RESULTS

Anthropometric assessment was used, and 36% of the girls were underweight, 47% were of normal weight, and 17% were overweight for their height. Of the 118 underweight students, 43% (n = 51) had

a body weight that was 20% or more less than their ideal body weight for height and 16% (n = 19) were

30% or more underweight. In contrast, of the 56 overweight students, only 39% (n = 22) were more

than 20% overweight for height.

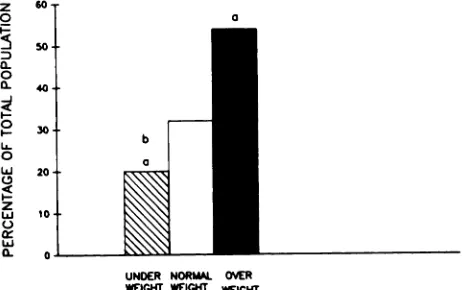

Dieting at the time of the survey was reported by the students regardless of whether they were

un-derweight, normal weight, or overweight (Fig 1). As many as 20% (n = 24) of the underweight girls were

dieting. Even four of the 19 students who were 30% or more less than their ideal body weight for height were dieting to lose weight. Almost one third of the girls of normal weight were dieting to lose weight (32%; n = 51). In contrast, only 54% (n = 30) of

the overweight girls in whom weight loss might be desirable were dieting at the time of the survey. A

z 0

UNDER NORMAL OVER

WEIGHT WEIGHT WEIGHT

Fig 1. Percentage of underweight (n = 118), normal

weight (n = 152), and overweight (n = 56) adolescent

20

0

0 0

0 0

0

S

0

S

0

U

>

U

I.

1)

Percent Ideal Body Weight

Fig 2. Significant overall positive correlation between distorted perception of idea! body weight (IBW) and percentage of IBW for all weight categories was noted (r

= .73; P < .001). Underweight () students had most distorted perceptions of their ideal body weight (r = .68;

P < .001), whereas norma! weight (0) and overweight (0) girls showed weaker but statistically significant cor-relations: r = .43; P < .001 and r = .27; P < .05, respectively.

50 00 #{149}0 $0 I#{243}Oho 120 130 140 150 ISO

I00#{149}

90

eo

70

-60#{149}

50-z

I

UNDERWEIGHT

=

NORMAL WEIGHT-

O#tRWEIGHTb

20-10

#{182}MffW4C UL TO WINO PEE- TLRflLD

r aNcEs

m soar FAT CHT

Fig 3. Proportion of inappropriate eating attitudes such as fear of obesity and ma!adapt-ive eating behaviors among 326 high school girls varies according to their body weights. Significant differences (P < .05) from normal weight group (a) and from overweight group (b) as determined by 2 test of independence.

recent history of dieting reported by the girls was

impressive; 72% of all students had made such

attempts to lose weight regardless of their body weight.

The concerns and anxieties of these adolescent girls regarding body weight were further seen in the frequency of self-weighing practices they reported. Girls who were underweight and normal weight weighed themselves as often as did overweight girls. The same applied to the 19 girls with severe body weight deficits for height. Of these adolescent girls,

55% (n = 179) weighed themselves at least every other week. The other 45% of the students also weighed themselves but at greater intervals. Of

those who practiced more frequent self-weighing,

21% (n = 37) weighed themselves every other week, 42% (n = 76) every week, 15% (n = 27) every other day, 18% (n = 32) every day, and 4% (n = 7)

reportedly weighed themselves more than once a

day.

Many adolescents had a distorted perception of their ideal body weight. Underweight and normal weight girls reported a distorted perception of their ideal body weight for height more often than did the overweight girls. In fact, the greater the under-estimation of perceived ideal body weight for height, the greater the deficit in ideal body weight of the students (r = .73; P < .001) (Fig 2). Those

students whose perceived ideal body weight for

height was less than actual ideal body weight for height were, indeed, underweight. The perceptions of ideal body weight of the students who were of normal weight and overweight appeared to be more

40-

30-appropriate, however. They had better concordance between their actual and their perceived ideal body weight.

Disturbed attitudes and eating behaviors were reported by the girls regardless of their body weight

deficits or excesses. As many as 51% (n = 60) of

the underweight adolescents reported extreme anx-iety about being overweight and 36% (n = 43) were

preoccupied with body fat. Norma! weight and over-weight girls expressed these concerns more

and vomiting behaviors were similar among the

three weight categories, including the severely un-derweight students.

General nutrition knowledge appeared to be in-dependent of the adolescents’ attitudes, eating be-haviors, and body weights. A similar level of nutri-tion knowledge was noted regardless of the

stu-dents’ body weight, and no differences in nutrition knowledge were demonstrated with relationship to reported dieting practices, frequency of self-weigh-ing, fear of being overweight or preoccupation with body fat, bingeing, impulse to vomit, or vomiting

behavior.

DISCUSS1ON

We described a fear of becoming obese among high school students that manifested itself regard-less of body weight or nutrition knowledge. Under-weight, normal weight, and overweight students were dieting and had frequent self-weighing prac-tices as common expressions of this fear of obesity. Additionally, the distorted perceptions of ideal body weight appeared to influence the student’s actual body weight. Those who perceived a low ideal body weight did indeed have a reduced weight. These distorted perceptions of ideal body weight were more common in thin students.

The prevalence of fear of obesity among adoles-cent girls in a suburban upper middle-class area in New York was similar to that reported by other investigations performed in a variety of ethnic and socioeconomic student populations.”3’27 In these previous studies, however, information regarding

the adolescents’ actual body weight or their weight in accordance to their height was not provided. Therefore, no relationship between the students’ perceptions, attitudes or behaviors, and their actual weights could be made. In contrast, in this study it was clearly demonstrated that fear of obesity and its related behaviors occur in students regardless of their body weight.

The desire for thinness as described in these adolescents does not appear to be a new phenome-non. As many as 20 years ago, a great prevalence of dieting to lose weight even among lean females was described by Dwyer et al.’ Bingeing and purging appear to be increasing among our adolescent pop-ulation as an inappropriate method of weight con-trol, however. Episodes of binge eating have been reported in 57% of 1,268 adolescent girls and self-induced vomiting in as many as 16%.27 However, when a weekly or greater frequency criterion for binge eating and vomiting was employed, these behaviors were reported in only 16% and 4% of the

girls, respectively. Among tenth-grade girls in Cal-ifornia, a 10.6% incidence of vomiting behaviors was described.4 In contrast, 26% of the girls sur-veyed in our study were bingeing and only 2% were vomiting. The discrepancy in the reported preva-lence of these behaviors may, in part, be due to the

lack of criteria for defining a “binge.” Because bulimia has been described as a continumun of behaviors and attitudes,28 in surveys such as ours in which rigid, all-or-none types of definitions of bingeing and vomiting are used, only the most severe cases may be identified; these may not rep-resent the entire spectrum of the problem. Recent

conservative estimates of the prevalence of bulimia among young women in western industrialized

countries are 1% to 3%#{149}2930 In those surveys27’31’32 in which a broader definition of purging behaviors is used, a more common problem among adolescents may be being described.

Regardless of the cause or type of eating disorder, the medical consequences of inappropriate eating practices such as dieting, bingeing, and vomiting can be quite severe. In our study, 36% of the ado-lescent girls weighed less than 90% of their ideal body weight for height and 16% had severe body weight deficits of more than 20% . Although this degree of undernutrition has been associated with growth retardation and nutritional dwarfing,8’33’34 the lack of growth records concerning these adoles-cent girls precludes stating whether the weight def-icits influenced the linear growth and development

of the girls surveyed.

Consistent with our observations, a high mci-dence of low-weight female students was also de-scribed in another study in which the growth rec-ords of 1,017 high school students from a similar

socioeconomic status and area of New York were reviewed. Of 503 girls studied, 25% were less than 90% of their ideal body weight for height and 1.8% exhibited linear growth retardation associated with poor weight gain.35 This type of growth pattern reflecting nutritional dwarfing was also described in patients with short stature and delayed pu-berty.8’36 Fear of obesity and other health concerns were often the reason for inadequate nutrition lead-ing to poor growth in such patients.8’37 In addition to nutritional dwarfing, excessive dieting, bingeing, and purging may lead to other medical complica-tions, including electrolyte disturbances, dental en-amel erosion, acute gastric dilation, esophagitis, enlargement of the parotid gland, aspiration phen-umonitis, and pancreatitis.38

REFERENCES

1. Storz NS, Greene WH: Body weight, body image, and per-ception of fad diets in adolescent girls. J Nutr Educ 1983;15:15-18

2. Dwyer JT, Feldman JJ, Seltzer C, Mayer J: Adolescent attitudes toward weight and appearance. J Nutr Educ 1969;1:14-19

3. Dwyer JT, Feldman JJ, Mayer J: Adolescent dieters: Who are they? Physical characteristics, attitudes and dieting practices of adolescent girls. Am J Clin Nutr 1967;20:1045-1056

4. Killen JD, Taylor B, Teich MJ, et al: Self-induced vomiting and laxative and diuretic use among teenagers: Precursors of the binge-purge syndrome? JAMA 1986;255:1447-1449 5. Mitchell JE, Pyle RL: The bulimic syndrome in normal

weight individuals: A review. mt J Eating Disord

1981;1:61-73

6. Johnson C, Stuckey M, Lewis L, et al: Bulimia: A descriptive survey of 316 cases. mt Eating D&sord 1982;2:3-16

7. Pyle RL, Mitchell JR, Eckert ED, et al: The incidence of bulimia in freshman college students. mt Eating Disord

1983;2:75-85

8. Lifshitz F, Moses N, Cervantes C, et al: Nutritional dwarfing in adolescents. Semin Adolesc Med 1987;3:255-266

9. Button EJ, Whitehouse A: Subclinical anorexia nervosa.

Psychol Med 1981;11:509-516

10. Davis R, Apley J, Fill F, et al: Diet and retarted growth. Br Med J 1978;1:539-542

11. Smith NJ: Excessive weight loss and food aversion in ath-letes simulating anorexia nervosa. Pediatrics 1980;66:139-142

12. Pugliese MT, Lifshitz F, Grad G, et a!: Fear of obesity: A cause of short stature and delayed puberty. N Engi J Med

1983;309:513-518

13. Garner DM, Garfinkel PE, Schwartz D, Thompson M: Cul-tural expectations of thinness in women. Psychol Rep 1980;47:483-491

14. Andersen AE: Anorexia nervosa and bulimia: Biological, psychological, and sociocultural aspects, in Galler JR (ed): Nutrition and Behavior. New York, Plenum Press, 1984, pp 305-338

15. Schwartz DM, Thompson MG, Johnson CL: Anorexia ner-vosa and bulimia: The sociocultural context. mt J Eating Disord 1982;1:20-36

16. Crisp AH: Anorexia Nervosa: Let Me Be. New York, Grune

& Stratton, 1980

17. Carino CM, Chmelko P: Disorders of eating in adolescence: Anorexia nervosa and bulimia. Nurs Gun North Am

1983;18:343-352

18. Searles RH, Terry RD, Amos RJ: Nutrition knowledge and dieting had greater nutrition knowledge than those

nondieting girls, whereas overweight girls had bet-ter nutrition knowledge related to weight control than normal weight girls. Even girls with anorexia nervosa have been shown to score higher on a nutrition knowledge questionnaire than matched

control girls with regard to questions concerning caloric content of food, dieting, and fiber, but their knowledge in other more general areas of nutrition was poor.39 Therefore, nutrition education during adolescence may not ameliorate the concerns of adolescents regarding their body weight. On the contrary, students may seek nutrition knowledge to combat their fears about being overweight and re-structure their eating habits to achieve their poten-tially inappropriate weight goals.

This problem of fear of obesity appears to be deeply engrained in our society as a result of the cultural preoccupation with obesity and the value placed on being slim. Television, magazines, and even the classroom promote the goal of thinness with regard to both beauty and health. Even in medical recommendations and in a number of other expert sources, a “healthier” dietary intake is pro-moted.40’4’ These recommendations appear to in-tensify concerns and rationalizations for self-in-duced dietary restrictions.8”6 This social phenome-non has an impact not only on adult and adolescent

eating habits but may also influence the eating habits of young children. Concepts regarding body weight and appearance are formed very early in life. In fact, elementary school children have been

shown to perceive obesity as being worse than being handicapped or disabled.42’4’

SPECULATION

AND

RELEVANCE

From a practical standpoint, it is important for physicians and other health professionals who are caring for adolescents to evaluate eating attitudes and practices as well as to identify the medical complications that may be associated with the types

of inappropriate eating behaviors described by ad-olescent girls in this study. With careful assessment of height and weight progression, those children who are not gaining in weight and growing appro-priately will be clearly identified.8 The pediatrician should also keep in mind that underweight adoles-cents may be dieting and have a distorted percep-tion of what their ideal body weight for height should be. Adolescents, regardless of their body weight, may frequently engage in inappropriate eat-ing behaviors such as bingeing and vomiting to combat their fears of becoming obese. To allow for adequate nutritional intakes, the adolescents’ con-cerns regarding obesity must be addressed.

SUMMARY

In summary, fear of obesity was a common phe-nomenon among the population of adolescent girls

body image satisfaction of female adolescents. J Nutr Educ

1986;18:123-127

19. Dwyer JT, Feldman JJ, Mayer J: Nutritional literacy of high school students. J Nutr Educ 1970;2:59-66

20. Whitehead FE: How nutrition education can affect adoles-cents’ food choices. J Am Diet Assoc 1960;37:348-356 21. Hinton MA, Eppright ES, Chadderdon H, et a!: Eating

behavior and dietary intake of girls 12 to 14 years old. J Am

Diet Assoc 1963;43:223-227

22. Radius SM, Dillman TE, Becker MH: Adolescent perspec-tives on health and illness. Adolescence 1980;15:375-383 23. Story M, Resnick MD: Adolescents’ views on food and

nutrition. J Nutr Educ 1986;18:188-192

24. Byrd-Bredbenner C: The Interrelationship of Nutrition

Knowledge, Attitudes Towards Nutrition, Dietary Behavior

and Committment to the Concern for Nutrition Education, thesis. Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA, 1980

25. National Center for Health Statistics growth charts. Monthly Vital Statistics Report, National Center for Health Statistics, vol 25, No. 3 (suppl), 1976

26. Zar JH: Biostatistical Analysis, ed 2. Englewood Cliffs, NJ,

Prentice-Hall, 1984

27. Johnson CL, Lewis C, Love S, et al: A descriptive survey of dieting and bulimic behavior in a female high school popu-lation, in Understanding Anorexia Nervosa and Bulimia: Report of the Fourth Ross Conference on Medical Research. Columbus, OH, Ross Laboratories, 1983, pp 14-20 28. Zuckerman DM, Colby A, Ware NC, et a!: The prevalence

of bulimia among college students. Am J Public Health

1986;76:1135-1137

29. Pyle RL, Halvorson PA, Neuman PA, et al: The increasing prevalence of bulimia in freshman college students. mt J Eating Disord 1986;5:631-647

30. Pyle RL: The epidemiology of eating disorders. Pediatrician

1985;12:102-109

31. Halmi KA, Falk JR, Schwartz E: Binge-eating and vomiting:

A survey of a college population. Psychol Med

1981;11:697-706

32. Johnson C, Lewis C, Hagmann J: The syndrome of bulimia: Review and synthesis. Psychiatr Clin North Am

1984;7:247-272

33. Viteri FE, Torun B: Protein-calorie malnutrition, in Good-hart RS, Shils ME (eds): Modern Nutrition in Health and

Disease, ed 6. Philadelphia, Lea & Febiger 1980, pp 697-720

34. Keller W, Fillmore CM: Prevalence of protein-energy mal-nutrition. World Health Stat Q1983;36:129-169

35. Pugliese M, Recker B, Lifshitz F: A survey to determine the prevalence of abnormal growth patterns in adolescence. J Adolesc Health Care 1988;9:181-187

36. Lifshitz F: Nutrition and growth, in Lifshitz F (ed): Clinical Nutrition and Growth Clinical Nutrition Supplement. St Louis, MO, CV Mosby Co, 1985, vol 4, pp 40-47

37. Lifshitz F, Moses N: Nutritional dwarfing: Growth, dieting, and fear of obesity. J Am Coil Nutr 1988;7:367-376

38. Herzog DB, Copeland PM: Eating disorders. N EngI J Med

1985;313:295-303

39. Beumont PJV, Chambers TL, Rouse L, et a!: The diet composition and nutritional knowledge of patients with anorexia nervosa. J Hum Nutr 1981;35:265-273

40. Weidman W, Kwiterovich P, Jesse MJ, et al: Diet in the healthy child: Task force committee by the Nutrition Com-mittee and the Council of Cardiovascular Disease in the Young Council, American Heart Association. Circulation 1983;67:1414A

41. National Institutes of Health Consensus Conference: Low-ering blood cholesterol to prevent heart disease. JAMA 1985;253:2080-2086

42. Brownell KD, Wadden TA: Confronting obesity in children: Behavioral and psychological factors. Pediatric Ann 1984; 13:473-480