BY

STEPHEN CHEGE WAIRURI (M.ENVS.) N85/13320/2009

A THESIS SUBMITTED IN FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN THE SCHOOL OF ENVIRONMENTAL STUDIES OF KENYATTA UNIVERSITY

DECLARATION

This thesis is my original research work and has not been presented for a degree in any other university or any other award. Where reference has been made to the work of others, credit has been given appropriately. This work should not be reproduced in part or whole without prior permission of the author and /or Kenyatta University.

Signed:... Date:... Stephen Chege Wairuri

Department of Environmental Studies and Community Development

SUPERVISORS

We confirm that the work reported in this thesis was carried out by the candidate under our supervision.

Signed:... Date:... Prof. James Biu Kung’u

Department of Environmental Sciences Kenyatta University

Signed:... Date:... Dr. Stephen Njoka Nyaga

DEDICATION

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

First and above all, glory and praise to Jehovah, the Almighty God for the opportunity and granting me the strength to proceed victoriously. Apart from years of study, this thesis reflects valuable relationships with many kind and resourceful people I have met. Their assistance and guidance have enabled this thesis to be in its current form. I would therefore like to sincerely thank all of them.

I am grateful to the Department of Environmental Studies and Community Development, Kenyatta University for giving me an opportunity to conduct this study. I am greatly indebted to my Supervisors, Professor James Kung’u and Dr Stephen Nyaga: thank you for accepting me as a Ph.D student. I am greatly indebted to your encouragement, thoughtful guidance, critical comments, and correction of the thesis. The trust, the insightful discussions, valuable advice, steadfast support during the whole period of the study, and especially for your patience and guidance during the writing process that made this thesis a reality. I cannot forget Dr Judy Wambui who provided important guidance and academic critique of my work during proposal development stage before she left Kenyatta University.

My thanks go to the Director, Kenya Forest Service (KFS) for the permission to interview staff from KFS. Many KFS personnel generously contributed their time and operational expertise to answering questions about conflicts in forest management. They include: Mathinji, Zonal Forest Manager, Kamau (Forester) Nanyuki Forest Station and Urbanus Katiwa. Thanks to Members of the Mount Kenya West-Nanyuki Community Forest Association and Meru Forest Environment Conservation & Protection Association (MEFECAP) for their assistance during data collection.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

DECLARATION ... i

DEDICATION ... ii

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ... iii

TABLE OF CONTENTS ... v

LIST OF TABLES ... ix

LIST OF FIGURES ... x

LIST OF PLATES ... xi

ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ... xii

ABSTRACT ... xv

CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION ... 1

1.1 Background to the Study ... 1

1.2 Problem Statement ... 7

1.3 Justification ... 7

1.4 Research Questions ... 8

1.5 Hypotheses ... 8

1.6 Objectives of the Study ... 9

1.7 Significance and Expected Outputs ... 9

1.8 Conceptual Framework ... 11

1.9 Scope and Limitations of the Study ... 14

1.10 Definition of Terms and Concepts ... 15

CHAPTER TWO: LITERATURE REVIEW ... 17

2.1 Introduction ... 17

2.2 Main Types of Natural Resource Conflicts ... 17

2.3 Decentralisation in Perspective ... 18

2.4 An Overview of Decentralised Forest Management Framework... 20

2.5 Forest Conflicts in the Context of Decentralisation ... 23

2.6 Evolution of Forest Management Framework in Kenya ... 27

2.6.1 Pre-colonial Period (Before-1895) ... 27

2.6.2 Colonial Period Forestry (1895-1962) ... 28

2.6.3 Post Colonial (1963 to Present) ... 29

2.7 Other Laws Affecting Forest Governance in Kenya ... 30

2.9 Literature Gaps... 35

CHAPTER THREE: RESEARCH METHODOLOGY ... 38

3.1 Introduction ... 38

3.2 Study Area ... 38

3.2.1 Meru County ... 38

3.2.2 Nyeri County ... 39

3.3 Research Design ... 40

3.4 Types of Data Collected ... 41

3.5 Study Population ... 41

3.6 Sample Size Determination and Sampling Procedure ... 42

3.7 Research Instruments ... 45

3.7.1 Documents Analysis ... 45

3.7.2 Semi-structured Interviews ... 45

3.7.3 Observation ... 46

3.7.4 Household Questionnaires ... 47

3.7.5 Focus Group Discussion (FGDs) ... 47

3.8 Instruments Validity and Reliability ... 48

3.9 Data Analysis and Presentation ... 48

3.10 Ethical Considerations ... 50

CHAPTER FOUR: RESULTS AND DISCUSSION ... 52

4.1 Introduction ... 52

4.2 Socio-demographic Characteristics of the Respondents ... 52

4.2.1 Gender of Respondents ... 53

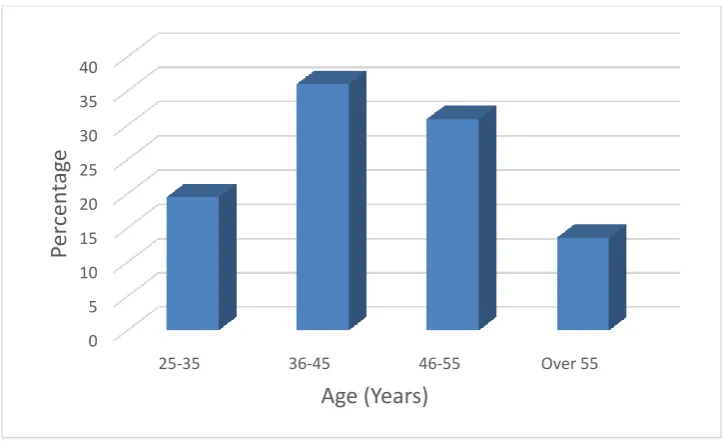

4.2.2 Age of Respondents ... 54

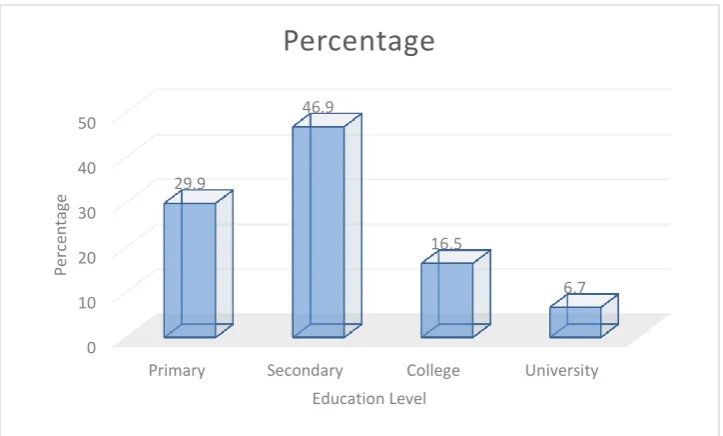

4.2.3 Education Level of the Respondents ... 55

4.2.4 Residing Distance from the Forest ... 57

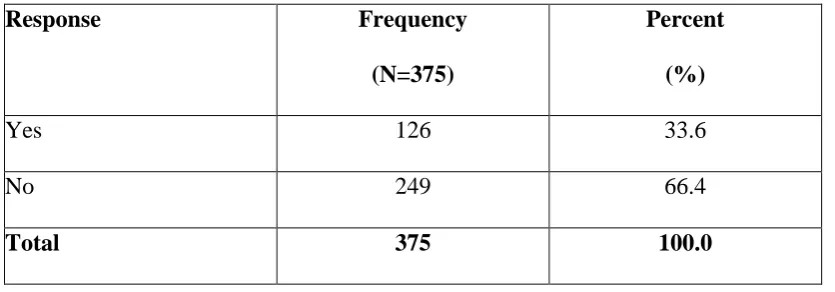

4.2.5 Membership of Respondents to Forest User Group (FUG) ... 58

4.2.6 Main Forest User Groups and Membership ... 59

4.2.7 Time of Stay by Respondents in the Study Area ... 60

4.3 Main Types of Conflicts in Mount Kenya Forest ... 61

4.3.1 Conflicts Before and After Decentralization of Forest Management ... 62

4.3.3 Conflict by Gender ... 79

4.4 Dynamics of Conflict and Decentralisation ... 85

4.4.1 Capacity Building ... 86

4.4.2 Legal Pluralism and Piecemeal Enactment of Rules ... 87

4.4.3 Governance of Community Forest Associations... 89

4.4.4 Trust Dynamics and Conflict in Decentralised Forest Management ... 91

4.5 Forest Access, Use and Management by FAC Before Decentralisation ... 97

4.5.1 Access and Use of Forest by Gender ... 99

4.5.2 Access and use of Forest by Forest User Group Membership ... 100

4.5.3 Participation in Forest Management ... 102

4.6 Conflict Management Styles Applied in Mount Kenya Forest ... 104

4.6.1 Forcing Conflict Management Strategy ... 105

4.6.2 Accommodating Conflict Management Strategy in Mt Kenya Forest ... 108

4.6.3 Avoiding Conflict Management Strategy in Mt Kenya Forest ... 109

4.6.4 Compromising Conflict Management Strategy in Mt Kenya Forest ... 113

4.6.5 Collaborating Conflict Management Strategy in Mt Kenya Forest ... 114

4.7 Comparison on Use of the Five Conflict Styles ... 117

CHAPTER FIVE: SUMMARY, CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS ... 120

5.1 Introduction ... 120

5.2 Summary of the Main Findings ... 121

5.3 Conclusions ... 123

5.4 Recommendations ... 125

5.5 Suggestions for Further Study ... 127

REFERENCES ... 128

APPENDICES ... 143

Appendix 1: Oral Informants ... 143

Appendix 2: Study Area Location ... 144

Appendix 3: Household Questionnaire ... 145

Appendix 4: Focus Group Discussion Guide ... 152

Appendix 5:In-depth Interview Guide ... 153

Appendix 6: Conflicts Experienced Before Forest Decentralisation ... 154

Appendix 7: Conflicts Experienced After Forest Decentralisation ... 155

Appendix 8: Impacts of Conflict Before and After Forest Decentralisation... 156

Appendix 10: Forcing Conflict Management Strategy Before and After Decentralisation of

Forest Management ... 158

Appendix 11: Accommodating Conflict Management Style in Mount Kenya Forest ... 159

Appendix 12: Avoiding Conflict Management Style in Mount Kenya Forest ... 160

Appendix 13: Compromising Conflict Management Style in Mount Kenya Forest... 161

Appendix 14: Collaborating Conflict Management style in Mount Kenya Forest ... 162

Appendix 15: Research Authorisation from Kenyatta University ... 163

Appendix 16: Research Permit from NACOSTI ... 164

Appendix 17: Research Permit from Kenya Forest Service ... 165

Appendix 18: Ruling on Forest Concessions Advertised by the Kenya Forest Service .... 166

Appendix 19: The Wildlife (Conservation and Management)(Mt Kenya National Reserve) Order 2000 ... 170

Appendix 20: Documents Analysed ... 172

LIST OF TABLES

Table 3.1: Human Population in Study Area ... 40

Table 4.1 Membership of respondents to Forest User Group ... 58

Table 4.2 Main Forest User Groups ... 59

Table 4.3: Conflict experienced in Mount Kenya Forest ... 62

Table 4.4: Change in forest user fees over time in the study area ... 70

Table 4.5: Inter organization conflicts ... 77

Table 4.6: Conflict mean scores... 78

Table 4.7: Paired Samples T-Test results for frequency of conflicts ... 78

Table 4.8: Gender differences in conflicts experienced ... 79

Table 4.9: Impacts of conflict before and after decentralisation ... 80

Table 4.10: Impacts of conflicts before and after decentralization by Gender. ... 81

Table 4.11: Forest Access, Use and Management by FAC ... 98

Table 4.12 Access and use of forest by local Community ... 99

Table 4.13: Access to forest benefits by membership to Forest User Groups ... 100

Table 4.14: Participation in forest management ... 102

Table 4.15: Participation in forest management across membership to FUGs ... 103

Table 4.16: Forcing conflict management style in Mount Kenya forest ... 106

Table 4.17 Application of Accommodation Conflict Management Strategy ... 109

Table 4.18: Avoiding conflict management style in Mount Kenya forest ... 110

Table 4.19: Compromising conflict management style in Mount Kenya forest ... 114

Table 4.20: Collaborating conflict management style in Mount Kenya forest ... 115

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure 1 Conceptual Framework ... 12 Figure 4.1 Gender Distribution of Respondents

LIST OF PLATES

ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ADR Alternative Dispute Resolution

CFA Community Forest Association CDTF Community Development Trust Fund DOC Document

EMCA Environmental Management and Coordination Act EWW Enterprise World Wide

FAC Forest Adjacent Community FAO Food and Agriculture Organization FD Forest Department

FGD Focus Group Discussion

FINNIDA Finnish Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Department of International Development

FMA Forest Management Agreement FMP Forest Management Plan FUG Forest User Group

FWG Forest Watch Ghana GOK Government of Kenya

IFAD International Fund for Agriculture and Development IMF International Monetary Fund

KEFRI Kenya Forest Research Institute KFS Kenya Forest Service

KII Key Informants Interviews KWS Kenya Wildlife Service LWF Laikipia Wildlife Forum

MEA Millenium Ecosystem Assessment

MEFECAP Meru Forest Environment Conservation & Protection Association MENR Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources

NACOFA National Alliance of Community Forest Associations

NACOSTI National Commission for Science, Technology and Innovation NAWASCO Nanyuki Water and Sewerage Company

NEMA National Environment Management Authority NGO Non-Governmental Organisation

NTFP Non Timber Forest Products NRM Natural Resource Management

NRWUA Nanyuki River Water Resource Users Association NWCPC National Water Conservation and Pipeline Corporation PELIS Plantation Establishment Livelihood System

PFM Participatory Forest Management PFMP Participatory Forest Management Plan SPSS Statistical Package for Social Sciences UNEP United Nations Environment Programme

UNESCO United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organisation USAID United States Agency for International Development

ABSTRACT

Many developing countries have been decentralizing some aspects of natural resource management. Governments justify decentralization as a means of increasing access, use, management, and decision making on natural resources. In Kenya, decentralisation

CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background to the Study

The term conflict has been contested due to some cultural underpinnings. As a result it is not uncommon to find an issue which is conflictual in one setting treated as quite normal in another setting. Conversely, the meaning of conflict is the product of complications and litigations that characterise our societies (Weeks, 1994). These confusions and complications aside, scholars have advanced various definitions; Putnam and Wondolleck (2003), Mayer (2003) and Peck (1996). These definitions converge at the point where they argue that inconsistent and incompatible actions, interests, behaviour norms and values among people form nerve centre of all conflicts. In other words one party is frustrating the other’s attempt to achieve something.

From a natural resource perspective conflict denotes divergent aims, methods or behaviour that emanate power differentials between stakeholders. The intensity of a conflict is a function of the breadth of the chasm between the main parties to a conflict. According to Krishnarayan (2005), conflicts are definite differences that exist between or among parties who have a certain type of relationship.

centralised governance. It was hoped that it would answer to the aforementioned crises. Examples from Asia, America, Africa and Europe illuminate the gusto with which decentralisation had swept natural resource management regimes the world over (Oyono, 2004).

The ‘Future We Want’, the key outcome of the Rio + 20 highlighted the social, economic and environmental benefits of forests to people and the contributions of sustainable forest management to realisation of Sustainable Development Goals (United Nations, 2012). The conference made a commitment to improving the livelihoods of people and communities. The improvement was to be achieved by creating the conditions needed for them to sustainably manage forests, strengthening cooperation arrangements in the areas of finance, trade, transfer of environmentally sound technologies, capacity-building and governance. In addition, focus is to be made in promoting secure land tenure and benefit-sharing, in accordance with national legislation and priorities.

reforestation globally” UN (2015:21). Realisation of such goals on a global level calls for actions of individual countries to formulate and implement innovative policies.

Nepal was an early leader in involving local communities in forest management programs (Agrawal, 1997). This came after the feudal tenure system was eliminated. The Nepalese Forest Act of 1961 made provisions for Community Forestry by providing recognition for village (panchayat) forests, Gautam and Devoe (2002). Towards the end of the 1980s the national government admitted that forest communities were the most suitable institutions for sustainable forest management and to take up forest management responsibilities (Singh and Kafle, 2000).

In Africa, as political reforms took place, so did natural resource governance. For instance, decentralisation of forestry management in Cameroon was launched in 1994, (Karsenty, 2002). After years of domination by the state (Diaw & Oyono, 1998), Forestry Code was revised in the year 1994. This revision paved way for the management and access of forest by the forest adjacent communities (FACs). The FACs started to reap more forest benefits without undue restrictions.

In Uganda, reforms in the forest sector were initiated in 1993 as part of the devolution policy of the government (Muhereza, 2003). However, the decentralisation has been criticised heavily as “The shift of powers through decentralization”. The results of decentralization in Uganda’s forestry were not evenly spread. The state held on to most forest management powers while limited powers were handed to district and sub-county councils. The Uganda Forest Department maintained control over the prized and bigger forest reserves (Muhereza, 2003).

On the other hand, the decade of the 80s in Kenya was also characterised by a deep economic recession and many internal imbalances. As a consequence the government implemented the structural adjustment programme imposed by the IMF (Timberlake, 1994). From the recession of the 80s, waves of protest marked the early 1990s.

These protests were aimed against the political regime which was accused of being corrupt, repressive, and socially unjust. These vices had permeated into all aspects of national life including the forestry sector management. As such every sector was crying out for reform if a total collapse was to be avoided. To save the forest sector, actors embarked on a process of reform as outlined in the Forestry Master Plan of 1994 (Mugo, et al. (eds) 2010). Thus, a convergence of factors were at the centre of decentralisation

of forest management in Kenya. These are political, economic, prompting from development partners, weakness of the central government and the wind of change blowing in other parts of developing world.

Looking at the policy and legal environment, Kenya can be considered a young entrant to forest decentralization league. Explicit legal and policy frameworks relevant to decentralisation of forest management did not exist until 2005 and 2007 respectively with the Act preceding the Policy. These have institutionalized decentralized forest management in Kenya with a widened stakeholder base. Decentralization and forest based conflicts have been researched on widely albeit independently.

Given that conflict is part of every society and is likely to increase with entry of more actors, it is important to ask questions like: How has entry of decentralisation affected conflict dynamics in forest use? Is there a change in the nature and frequency of conflicts in forestry? And lastly, what conflict management mechanisms are commonly used given the multiplicity of actors?

1.2 Problem Statement

The purpose of forest management decentralisation in Kenya is to improve forests through participation of forest adjacent communities and other interested actors in making management decisions. Decentralisation has altered the power relations among these actors. These altered relationships have a bearing on forest conflicts in the study area. Thus, the relationships between decentralisation and forest resource conflicts require scholastic attention. Considering the value of forest resources, the conflicts deserve examination. The study therefore fills this theoretical and empirical gap on the relationship between decentralisation and conflicts in forest management in Mount Kenya.

This study sought to analyse how forest management conflicts forest have been affected by forestry decentralization reforms in Kenya. How has decentralised forest management generated, exacerbated, or otherwise influenced conflict. The study identified whether since the advent of a decentralised forest management regime, conflicts have increased or decreased. It explored the dynamics of conflicts being experienced under the new system, impacts of these conflicts and conflict management strategies being used. In other words, the study investigated what has been the result of the intersection between decentralised forest management and conflicts in Mount Kenya forest.

1.3 Justification

stakes. These actors include among others Kenya Forest Service (KFS), Kenya Wildlife Service (KWS), Water Resources Management Authority (WRMA), Nanyuki River Water Users Association (NRWUA), small scale farmers, large scale farmers, and pastoralists. There is also a large population that sees the forest as their only source of livelihood. Lastly various conflicts over management and utilisation of resources have played out in the recent past between stakeholders. Kieni East and Meru Central were selected because in the recent past conflicts between actors have been reported.

1.4 Research Questions

The following questions guided the study:

1. Which are the main conflicts experienced in Mount Kenya forest?

2. How do conflict dynamics link with decentralization of forest management in Mount Kenya forest?

3. What are the strategies for managing conflicts in Mount Kenya forest?

4. How has decentralisation policy affected local communities’ access, use and management of Mount Kenya forest?

1.5 Hypotheses

1. Decentralisation of forest management has significantly reduced conflicts in Mount Kenya Forest.

2. Forest decentralisation has led to significant increase in access, use and management of Mount Kenya Forest by the local community.

1.6 Objectives of the Study 1.6.1 General Objective

The general objective of this study was to analyse how conflict dynamics in Mount Kenya Forest have been influenced by decentralized forest management regime. 1.6.2 Specific Objectives

Specifically the study sought to:

1. To identify and evaluate the main types of conflicts arising in the implementation of decentralised forest management policy in Mount Kenya forest.

2. To assess conflict dynamics and the link to decentralisation in Mount Kenya Forest.

3. To assess preferred conflict management strategies employed in Mount Kenya forest.

4. To identify the impact of decentralisation policy related conflicts on local communities’ access, use and management of Mount Kenya forest.

1.7 Significance and Expected Outputs

The study is thus significant to the society and the scientific community. With regards to societal significance, the study revealed how stakeholders interact, especially the reasons behind emergence of cooperation and conflict in the context of decentralisation. Participation has brought mixed outcomes.

In some cases it has resulted in cooperation while in others conflict has emerged. Understanding these responses will enable a better implementation of decentralisation processes and sustainable management of the forests. The study is relevant scientifically because it contributed knowledge in the field of conflict in decentralised forest management.

It has developed a conflict management framework for Mount Kenya Forest. This is based on the preferred conflict management approaches by the different actors. Conflict frames were essential to this end. Lastly, the study has highlighted need for harmonisation of policies for the Lead Agencies. These are KFS, KWS and WRMA to avert destructive conflicts.

This research has provided valuable information for reflection and action. It is hoped that this will encourage and help organisations and individuals involved in forest policy decisions to manage forest related conflicts and resolve them productively. This will however depend on whether there will be political will.

1.8 Conceptual Framework

Figure 1.1Conceptual Framework: (Researcher, 2013)

According to Walker and Daniels (1997) and Daniel’s and Walker (2001), every conflict consists of substantive, relational and procedural dimensions. A substantive dimension denotes the “tangible” aspects of a conflict situation (Walker, 2003). Relationship between or among parties to a conflict is addressed by the relational dimension. The relationship dimension is centred mostly around the history of the parties touching on trust, power, respect, legitimacy and influence.

DECENTRALISED FOREST MANAGEMENT

Relationship

Devolution Delegation Deconcentration

Substance

Procedure

Conflict Management Strategies

Force.

Withdrawal.

Compromise

Avoidance

Procedural dimension includes conflict management and decision making. Within it are various rules and regulations which the parties have committed themselves to observe. (Walker, 2003).

The changes brought about by decentralisation of forest management under Forest Act 2005 affected the three dimensions of the Conflict Progress Triangle. Consequently, the dynamics of conflicts and access to benefits have been altered. To address these conflicts, various strategies are employed by the actors. The choice of strategy is dependent mainly upon the power and interest a party has on the contested matter. Five “conflict-handling modes,” include competing, collaborating, compromising, avoiding, and accommodating. These modes can be described either as assertive or cooperative. Assertive strategies describe the extent to which a party seeks to satisfy his/her own concerns while cooperative strategies refers to the extent to which a party tries to satisfy the concerns of another party (Thomas & Kilman, 2004).

conceptual framework guided the crafting of sub-themes for the study objectives. Finally, the conceptual framework helped in synthesising and crafting summary, conclusions and recommendations.

The conceptual framework was found adequate for investigating and understanding the main issues that the research sought to understand. It proved effective in exploring the types of conflicts being experienced in the study area; levels of conflict and causes of conflict. Most importantly, it shed light on strategies being employed to address the conflicts. The shortcoming of the conceptual framework was its inability to answer questions regarding the intensity, duration and the likely future scenario should the circumstances continue unfolding with the current trend. Such issues could be answered by frameworks borrowing from political ecology theories and new institutionalism. However these (intensity, duration and future scenarios) were not the subject of the study. Thus, the study questions were answered and objectives met with this conceptual framework.

1.9 Scope and Limitations of the Study

The information sought by the study was sensitive in nature. Thus not all respondents’ were willing to give information in detail.

Thus the findings hold for the gazetted Mount Kenya forest study area. While generalisation can be made to other gazetted forests, caution is called for.

The respondents were drawn from Kenya Forest Service (KFS) staff, Forest Adjacent Community (FAC) members, and Community Forest Association (CFA) members. This is because they have a direct stake in the forest. They are also key in decision making with respect to the Mount Kenya forest.

1.10 Definition of Terms and Concepts

Community Forestry: Abranch of forestry where the local community and other actors including, government and non-government organisations (NGO’s) plays a pivotal role in forest management and land use decision making.

Conflict: Incompatibility between or among parties due to differences of interests, values, behaviour and attitudes

Conflict Management: It denotes the various ways by which people handle

grievances—upholding what is considered to be right and against what they consider to be wrong.

Decentralisation: The ceding of certain powers and accompanying authority from the central government to low tier units such as counties, districts or provinces. Legal pluralism: A situation where more than one legal regime is operating in a social

field.

Stakeholder: Any party interested in the utilisation and management of natural resources located in a place. There are primary, secondary and tertiary stakeholders.

Structural conflict: Embedded social, cultural, economic, legal and political hierarchies that predispose people to negative consequences.

CHAPTER TWO: LITERATURE REVIEW 2.1 Introduction

This chapter presents reviewed literature related to the study’s focus of conflict dynamics in implementation of forest decentralisation policy. Analysed literature is guided by themes addressed by the study’s objectives. Specifically, the chapter analyses literature under four main themes; namely, conflicts over natural resources; the intersection of decentralisation and natural resources conflicts; natural resources access; factors affecting access, use and management by local communities and conflict management approaches. These themes are further hinged on the elements of the conceptual framework that guided the study.

2.2 Main Types of Natural Resource Conflicts

As noted earlier, conflicts are definite differences between related parties. Krishnarayan (2005) contends that the root of all conflict can be traced in power differentials among stakeholders involved in the utilisation and management of natural resources. The power differentials result from difference in wealth, gender, social class,and race, among others. Existing rules and regulations have vested authority (a form of power) vested on some stakeholders. The ways in which any players uses power can generate conflict if it is unacceptable to others.

Most often it has been assumed that a conflict involves just two parties. However, practical experience shows that underneath the visible parties are other interests involved (Krishnarayan, 2005).

Power imbalances inform most if not all human relationships including natural resource use. However, if those imbalances are unarticulated, the conflict is latent. Emergent or open conflict is characterised by among other things, physical confrontation, and violence between or among resource users, walkouts, boycotts and in some cases full scale war. Formal or informal mechanisms, for managing power differences include systems of permits, harvesting quotas, patrols and collaboration among users in an agreed forum. If these mechanisms fail or breakdown due to whatever reason, conflict becomes inevitable (Krishnarayan, 2005).

Grimble and Wellard (1997) argue that categorisation of conflicts can be based on the level at which they manifest. Thus, they can be categorised in terms of whether they occur at the micro-micro or micro-macro levels. Micro-micro conflicts can further seen as either those within the group utilising a particular resource or between this group and those not directly involved (Conroy et al. 1998).

2.3 Decentralisation in Perspective

“Devolution” or “substantive decentralisation”.

In all its forms, there is consensus that decentralisation must involve some ceding of power by the central authority to a peripheral entity. However, most accepted definition of decentralisation was coined by Rondinelli et al. (1983). They defined decentralization as the transfer of various powers from the central government to other legal entities. The power transferred include planning, decision making and administrative powers. The four forms of decentralisation are defined depending on the amount and type of power ceded to the peripheral entity.

Manor (1999) and Ribot (2003) contend that democratic decentralisation (devolution) is the most suitable form of decentralisation. Under devolution, entities representing local populations are elected and have contractual obligations to electorate thus are accountable to them (Ribot, 1999). In earlier years, the theoretical debate in decentralisation centred on local government and on ‘politics’. However, there is a notable shift and now it is increasingly echoed in natural resources management (Fisher, 1999; Larson, 2002; Ribot, 2003)

(Mukandala, 2000) which are prone to conflict. To realise environmental sustainability, decentralisation is therefore a necessity (Fiszbein, 1997; Ribot, 2002).

It is worth noting that most developing countries have decentralised their governance

structures. Studies by Schreckenberg et al. (2006) found that many of these countries

have decentralized various aspects of natural resource management. Motivations for

decentralizing vary greatly across jurisdictions. Donors and governments cite

increasing actor’s power in the management of natural resources as the cornerstone for

decentralisation. It should be appreciated that decentralisation alters the institutional

landscape for natural resource management at the local level (Ribot, 2002). This

consequently affects stakeholders albeit in different ways.

2.4 An Overview of Decentralised Forest Management Framework

Over the years, there has been a global shift in the way forest resources are managed. Natural resource management has been greatly devolved to local institutions, both public and private. According to Edmunds and Wollenberg (2004) and Arnold (2001), policies guiding this decentralisation trends have been driven by: desires to reduce the control and costs incurred by the state in the conservation of forests; perception that local control can be a livelihood guarantee for the masses; a belief that decentralisation responds more to local needs while utilising skills available at the local level and commitment to people’s participation in matters that concern them.

decentralised forest management programmes in Nepal and India were conceived when state institutions failed to manage and protect the forests.

In Nepal and India, Leasehold Forestry and Joint Forest Management respectively were further driven by the desire to alleviate poverty and consequently improve livelihoods (Thomas et al. 2003; Khare et al. 2000). Governmental decentralisation programmes has increased local communities’ involvement in forest management in developing countries. For instance, in Honduras and Bolivia, municipal authorities are responsible for forest management (Nygren, 2005).

In other jurisdictions, PFM programmes have been developed with the assistance of development partners, political organisations and NGO’s. These programmes have resulted from recognition of local people’s rights to natural resources (Djeumo, 2001). The international community supported decentralisation and public sector reform in a bid to achieve sustainability and efficiency. This international support has been highly ranked as a key promoter of PFM according to Hobley, (1996).

which because of its direct link with FACs, has often been assumed to be positively correlated with poverty reduction.

According to Brown and Schreckenberg (2001), a host of management arrangements and objectives are subsumed under PFM. These arrangements depend on the type of forest and the benefits being pursued. For example community consultations are conducted prior to industrial logging operations in high value forest in the tropical areas. In others, communities must be fully involved in operations such as logging and timber transformation.

On the other hand, biomass regeneration, fuel wood production, commodity chain and community plantations are common place in lower value tropical dry forests (Coleman et al. (2007). Other benefits include Non-Timber Forest Products (NTFPs) and bush meat. The range of partnerships has expanded considerably to include plantation and out-grower schemes, carbon sequestration programmes, forest based ecotourism and other forest enterprises such as conservation-linked production schemes (Underwood, 1999).

whether power was devolved; the degree of participation, ownership and control; and what characterised management before introduction of PFM.

2.5 Forest Conflicts in the Context of Decentralisation

Top-down approach management of natural resources was pursued throughout the last century. In most cases, states owned natural resources which were managed through strict laws which excluded local populations (Stoll-Kleemann et al. 2010). This strict exclusive approach was counterproductive in several ways. It adversely affected the living conditions of the local communities since the natural resources were critical for their livelihoods. Worse still this fortress approach achieved very little in terms of conservation (Masozera et al. 2006). To reverse this destructive trend, involvement of local communities in natural resources management was recognized as critical for its success (Torquebiau and Taylor, 2009; Rodriguez-Izquierdo et al. 2010). If sustainable management of natural resources is to be realised, involvement of public is not optional (Leskinen, 2004).

Pragmatic arguments, hold that participation legitimises policy while enhancing the effectiveness of governance (Leeuwis, 2004; Coenen, 2009). It further argues that participation creates an avenue for accessing vital information, insights and skills. It also illuminates likely problems and their possible solutions (Leeuwis, 2004). As a result, this lessens the chance of policies being contested while enhancing the value of the resolutions arrived at (Stirling, 2006).

Normative arguments of participation are anchored on moral entitlement and civic duty of citizens to be involved in the formulation of policies that affect them (Leeuwis, 2004). Normative arguments assert that citizens are always ready and willing to engage with bureaucrats in appropriate platforms provided the bureaucrats will listen and take action (Corn-wall and Coelho, 2007). This involvement of the public in decision-making should increase awareness and ultimately cause behaviour change by the participants (Coenen, 2009).

In natural resource management, active participation of stakeholders in treasured. This is because it enhances accountability of those in charge of projects implementation.

Participation increases the stakeholders’ degree of control over how finances will be spent and what will take precedence. Consequently, accountability is enhanced. This increases effectiveness and legitimacy from an ethical perspective (Leeuwis, 2004). When the constituents exercise accountability as a countervailing power, participation is likely to be effective (Agrawal and Ribot, 1999; Ribot, 2001).

Scholars (Buckles and Rusnak, 1999; Castro and Nielson, 2003; Hares, 2009) argue that in management of natural resources, conflicts are inevitable and persistent. In the participatory management of natural resources, power relations among actors have often been cited as the epicenter of conflicts. Critics of participation blame power relations between and among stakeholders as the key source of conflicts (Chambers, 1997; Cooke and Kothari, 2001; Parfitt, 2004; and Arrts and Leuwis, 2010).

According to Aarts and Leeuwis (2010), effective citizen participation is consistently thwarted by lack of clarity about the government’s role and its power in participatory policymaking. They argue that in situations where people mobilise themselves to work towards a certain goal, power differentials, shows of power and power strife’s, will be present. Parfitt (2004) holding to Chambers’ perspective, maintains that power is a negative influence which is misused by the powerful to trample upon the weak.

Conflicts are the result of meaning and interpretation people attach to events and happenings in which they are party to. How people construct meanings and make sense of what is taking place (events and actions) are associated with framing (Entman, 1993; Gray, 2003; Dewulf, 2006; Dewulf et al. 2009).

2.6 Evolution of Forest Management Framework in Kenya

Evolution of forest management in Kenya can be traced to the pre- colonial, colonial and post-colonial stages. The social, economic and political realities of each of these epochs is reflected in the policies. The policy outcomes in each phase were tailored to meet specific objectives in line with the epoch in question.

2.6.1 Pre-colonial Period (Before-1895)

Before Kenya was declared a protectorate of the British Empire, management of forest resources, was through indigenous rules and rights. The rules were enforced by councils of elders. Sustainability of forests was ensured through sanctions and fines. The traditional management systems had a bias towards religious and cultural underpinnings of the communities (Castro, 1988; Luke and Robertson, 1993 and Ongugo and Mwangi, 1996).

Amongst the Luhya in Kakamega, forests were owned collectively by the community but management was vested upon clans living in proximity to the forest (Ongugo and Mwangi, 1996). Conversely, among the Kikuyu and Embu communities, forest land up to two miles into the forest was owned by clans (Castro, 1988). The other land beyond this line was owned by the community.

Bringing new forest land under cultivation was only possible after community members had consulted and reached an agreement. These examples testify of a functional natural resource management system prior to colonization. This system was devoid of unilateralism which characterized the colonial era administration and that was perpetuated in the post-colonial era.

2.6.2 Colonial Period Forestry (1895-1962)

According to Logie and Dyson (1962), Ukamba Woods and Forest Regulation of 1897 was enacted as the first colonial forest law in Kenya. This regulation was crafted to primarily ensure that fuel supplies for railway locomotives were guaranteed. Under this law, all forests within one mile of the railway line were controlled by the railway authority. Other forests outside the railway authorities were administered by the District Officers.

The FACs were now required to have permits in order to access forest resources. The policies resulted to: displacement of populations, alienation of settlers, and acrimony between Forest Department and local population (Mwangi, 1998).

2.6.3 Post Colonial (1963 to Present)

After independence, forest management in Kenya was provided by the Forest Act, Chapter 385 of the Laws of Kenya of 1942. This Forest Act was thus a colonial relic. The Act was enacted by Parliament to provide for "the establishment, control and regulation of central forests, and forest areas in the Nairobi area and any unalienated government land. The Act gave the Minister in charge of forests far reaching powers including degazettement of forests and declaring forest land. It also stipulated that the Minister should give a 28 –day notice prior to degazettement of any public forest (GOK, 1982). This prior notice was meant to provide an avenue for participation but it achieved very little in deterring destructive forest activities.

The results of this policy were felt greatly by early 1990s. The forest sector was tottering on the brink of complete breakdown. Low or no-existent participation of stakeholders and political interference in management were twin evils that led to massive forest losses in Kenya. With assistance by FINNIDA, the Kenya Forestry Master Plan Project (KFMP) recommended far reaching reforms in legislation, policy, institutions, and programmes (Ogweno, et al. 2009).

These reforms culminated in Forest Act 2005 and Forest Policy 2007 later. A notable inclusion in this Draft Policy was the role of community participation. Enactment of the Forest Policy, 2007 has greatly altered the forest management landscape in Kenya. The centralized command and control approach has been replaced by the decentralized participatory forest management (MENR, 2007 A), a subject of this study.

2.7 Other Laws Affecting Forest Governance in Kenya

The 1974 Water Act was revised in the year 1999 and 2002. The result was Water Act 2002 whose main focus was decentralisation of water services and separating water policy formulation from regulation and services provision. Services were decentralised to the regional level with creation of Water Services Board (WSB), Water Service Providers (WSP), and Water River Users Associations (WRUA) (Republic of Kenya, 2002). There are also Catchment Area Advisory Committees (CAACs) created under the Water Act. The mandate of CAACs somehow infringes on KFS roles. These institutions especially the WRUAs have been in constant contentions with the CFAs on who is superior.

The Wildlife Conservation and Management Act, 2013 provides for: protection, conservation and sustainable use and management of wildlife in Kenya and for connected purposes. The Act vests wildlife (flora and fauna) conservation to the Kenya Wildlife Service (KWS) and far reaching powers in so far as conservation of biodiversity is concerned. This places it on a collision course with KFS which is the custodian of the forests where the biodiversity thrives. The KWS is also the focal point of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Flora and Fauna (CITES). The endangered species are to be found in various ecosystem with the KFS managed forests being a major reservoir.

(EMCA, 1999). The constitutional elevation of this right came with current constitution of Kenya which was promulgated in the year 2010.

The new constitution is awash with environmental provisions. Thus if enforced, the country will reap great dividends in environment and natural resources conservation. Environmental provisions are found in Chapter Four, which is titled, ‘Rights and Fundamental Freedoms’, Chapter Five, under ‘Environment and Natural Resources’, and Chapter Ten, under ‘Judicial Authority and Legal System’. The Fourth Schedule also has environmental provisions under ‘Distribution of functions between National and County governments’ and Fifth Schedule titled ‘Legislation to be enacted by Parliament’.

The Constitution presents environmental rights and freedoms Article 42 where it states that every person has the right to a clean and healthy environment (Republic of Kenya, 2010). Chapter Five of the Constitution of Kenya is titled ‘Land and Environment’ consists of two parts. The first part is dedicated to land and the second to environment and natural resources. Individual citizens are committed with the role of environmental management by the constitution in the second part of Article 69 of the constitution. The constitution requires every person to cooperate with state organs and other persons to protect and conserve the environment and ensure ecologically sustainable use of natural resources (Republic of Kenya, 2010).

environmental legislation in Kenya is the Environmental Management and Coordination Act of 1999 (EMCA 1999). Subsidiary legislations have also been enacted to support EMCA.

The constitution of Kenya provides for two levels of government. That is the National and County governments. Each government has been assigned distinct responsibility over the environment and natural resources as spelt out in the Fourth Schedule. The National Government protect the environment and natural resources with a view to establish a durable and sustainable system of development (Republic of Kenya, 2010).

Thus, the national government has macro-level of influence on environmental conservation and management. On the other hand, the County Governments are responsible for with the responsibility of implementing specific national government policies on natural resources and environmental conservation, including soil and water conservation and forestry (Republic of Kenya, 2010).

2.8 Management Strategies for Natural Resource Conflicts

On the other hand, various strategies for conflict management have been crafted. Khun and Poole's (2000) model consists of the distributive and integrative sub-models. The distributive sub-model aims to have each party win some concessions. It builds up confidence in the individuals and make each think that they are benefiting. The integrative sub-model try to integrate the needs of both parties and meet halfway. Integrative sub-model has been shown to be more effective than the distributive model (Khun and Poole, 2000).

The DeChurch and Mark's (2001) Meta-Taxonomy Model, posits two viewpoint in regard to conflict strategy. The first viewpoint is activeness and involves a party’s directness in solving a problem. Actors are direct and assertive with what they want out of negotiations or they are passive and unpleasant. The other viewpoint is agreeableness, where the parties are judged depending on their temperaments. Consequently, parties who are more hostile to each other are might take, longer to reach a compromise or they may not compromise at all.

Compromising involves a give and take solution where both parties attempt to relinquish some goal that they may have in order to gain in another aspect of the negotiation. These approaches work well in different conflict situations.

According to Thomas and Kilmann (2004), an individual’s behavior in conflict situations can be described as either assertive or cooperative. Assertiveness denotes “self-focusing” strategies the actor seeks to satisfy his or her own concerns while cooperativeness is the “other-focusing” strategy where the actor works to satisfy the other person’s concerns. Like the Rahim approach, five methods of dealing with conflict are derived. Thus an actor in conflict can either: avoid, accommodate, compete, compromise or collaborate. Avoiding strategy orients toward neglecting conflict while accommodating lean towards concession.

Conversely, competing strategy is based on gaining favourable outcomes by using power and authority, whereas compromising strategy seeks for sharing. Finally, collaborating strategy orients towards integration. This approach compares well with Rahim’s. Each of the strategy has different outcomes especially on the relationship between the conflicting parties.

2.9 Literature Gaps

resources. Decentralisation of forest management is one such change and it has been as a result of policy change. Decentralisation has been labelled differently in different parts of the world. It has been called Joint Forest Management; Participatory Forest Management or Community Based Forest Management. In Kenya, it has been referred to as Participatory Forest Management. Are these conceptualisations one and the same? Are their outcomes similar or are the outcomes context specific especially with regard to conflicts? Available literature is yet to answer these questions sufficiently.

Literature also reveals that much has been done as far as NRM conflicts are concerned. Decentralisation has also been commented on extensively. However, how conflicts in NRM are affected by decentralisation and vice versa are still a grey area. In Kenya, numerous studies have focused on PFM in general terms. However, the extent to which it has affected or is affected by conflicts remains quite open. The enduring question is: what happens when conflict meets decentralisation and vice versa? This is the gap that this current study endeavours to contribute in filling.

Finally, existing literature acknowledges the diverse conflict management strategies. It also acknowledges their use in different contexts. However, literature falls short of showing how the use of different conflict management strategies has been affected by decentralisation of forest management. This means that an opportunity has been lost for improving what has been found to be working by borrowing best practices.

CHAPTER THREE: RESEARCH METHODOLOGY 3.1 Introduction

This chapter presents information on methodology used in the study. It begins with a description of the area where the study was conducted. It exemplifies the research design that guided the study. The chapter also explains how the sample size was determined and how respondents were picked. The chapter further provides information on techniques used to collect both primary and secondary data and shows how the data was analysed. The chapter also sheds light on methods used to analyse data obtained through the use of techniques above. In a compendium therefore, the chapter presents and discusses the steps adhered to in understanding the dynamics of conflict in decentralised forest management.

3.2 Study Area

The study focused on the geographic area covered by two Sub-Counties in Mount Kenya Forest namely: Kieni East in Nyeri County and Meru Central in Meru County (Appendix 2). The forest occupies part of Laikipia, Nyeri and Kirinyaga Counties to the West and Embu, Tharaka Nithi and Meru Counties to the East. The area around the slopes of Mount Kenya is densely populated. This is due to availability of arable soils and high reliable rainfall that favours rain fed agriculture. The two study sites in Meru and Nyeri Counties were purposively selected for the study.

3.2.1 Meru County

south west, Tharaka/Nithi to the east and Isiolo to the North. It straddles the equator lying within 00 6’ North and about 00 1’ South, and latitudes 370 West and 380 East. The county has a total area of 6,936.2 KM2 out of which 1,776.1 KM2 is gazetted forest.

In Meru County, close to one-third of land is suitable for agriculture and this ranks highly in Kenya’s food production. The County has four agro ecological zones (GOK, 2002; Jaetzold and Schmidt, 2009). Small land holders control economy of the area mainly through mixed farming (i.e. crop cultivation and animal husbandry (Jaetzold and Schmidt, 2009; County Government of Meru, 2013).).

3.2.2 Nyeri County

On the other hand, Nyeri County is located in the central region of the country. It covers an area of 3,337.2 Km2 and is situated between longitudes 36038” east and 37020”east and between the equator and latitude 00 380 south. It borders Laikipia County to the north, Kirinyaga County to the east, Murang’a County to the south, Nyandarua County to the west and Meru County to the northeast (County Government of Nyeri, 2013).

Table 3.2: Human Population in Study Area

County Population Land Area in km2 Population Density

Meru 1,356,301 6,936.2 196

Nyeri 693,558 2,558.9 368

Source: Kenya National Bureau of Statistics-National Population Census, 2009.

3.3 Research Design

The study used the descriptive survey research method. This design was found to be the most appropriate for the study because it allows for pre-planning and structuring so that the information collected can be statistically inferred on a population. In addition, it enables a researcher to better define an opinion, attitude, or behaviour held by a group of people on a given subject. The subject of conflict and decentralisation which was under investigation thus rendered itself suitable for investigation with this design.

3.4 Types of Data Collected

The study used both secondary and primary data. The specific data sets that were collected include: Types of stakeholder conflicts, Effects of decentralisation policy on conflicts, preferred conflict management approaches, and access and use of forest resources.

3.5 Study Population

The target population for the study comprised of all the inhabitants of Kieni East and Meru Central sub-Counties. They were 324,659 and 141,769 persons respectively (Republic of Kenya, 2009). Thus, giving a total population of 466,427. Key Informants for the study were drawn from the Lead Agencies represented by Kenya Forest Service and Kenya Wildlife Service; Civil Society Organisations represented by Laikipia Wildlife Forum and National Coalition of Forest Associations, (NACOFA), and Community Forest Associations, Forest User Groups, and Water Resource Users Associations.

The last category of respondents were the “Reformed illegal loggers”. These are among members of the FACs but has in the past been accused of illegal activities in the forest. Some have even been arraigned in court. The researcher was able to interview six such people.

3.6 Sample Size Determination and Sampling Procedure

From the target population, a representative sample was determined using the formula by Krejcie and Morgan (1970), which is used to calculate a sample size (s), from a given finite population (P) such that the sample will be within plus or minus 0.05 of the population proportion with a 95 percent level of confidence. This formula is presented below.

Where:

X2 = table value of Chi-Square for 1 degree of freedom at the desired confidence level (in this case 3.84)

N = the population size, in this case 466,427

P = the population proportion (assumed to be 0.5 since this would provide the maximum sample size)

d – the degree of accuracy expressed as a proportion (0.05) X2NP(1 – P)

s

Computing the desired sample size using this formula gave 384 as the minimum number of respondents that should be selected from the population. Therefore, the sample size for the household heads was 384 respondents. The sample was proportionately distributed to the two study sites depending on the overall population size. Nyeri North was allocated 70% (269 respondents) of the sample while Meru Central was allocated 30% (115 respondents) of the total sample. During data cleaning, 9 questionnaires were found to be improperly filled and so they were discarded. Thus, the final tally of questionnaires that were analysed was 375. In addition, 14 Key Informants were interviewed and four FGD’s (two in Nyeri and Two in Meru) conducted (Appendix 22).

The study used different sampling techniques in respondent’s selection. This was needful so that the array of actors could be represented in the final sample. Apart from that, this was necessitated by the study approach. Household heads were randomly selected using simple random sampling. This allowed all the household heads an equal chance of being picked for the final sample. A sampling frame was developed with the help of village elders who know household heads in the sub locations that adjoin the forest. Then applying the lottery method, individual households were selected. The household closest to the forests were first to be picked.

individuals, or activities selected. Second, purposive sampling can be used to capture adequately the heterogeneity in the population. Third, a sample can be purposefully selected to allow for examination of cases that are critical for the theories that the study began with. Finally, purposive sampling can be used to establish particular comparisons to illuminate the reasons for the differences between settings or individuals, a common strategy in multi-case qualitative studies.

Purposive sampling was appropriate in the study because it stresses in-depth investigation in a small number of communities. The emphasis was in quality not quantity, the objective was not to maximise numbers but to become “saturated” with information on the topic (Padgett, 1998).

3.7 Research Instruments

Data collection methods were dependent upon the type of data to be collected which in turn was dependent upon specific study objectives. The following research instruments were also important so as to address the matters of depth, breadth, reliability and validity.

3.7.1 Documents Analysis

The use of documents is a major source of data in social sciences (Sapsford and Jupp, 1996). Documents drawn on in this research included official documents such as the Mt Kenya Ecosystem Management Plan, Participatory Management Forest Plans for Nanyuki and Meru Forests, Court rulings on various disputes, Letters, Minutes of CFA meetings, and Newspapers (Appendix 8). Documents revealed, among other things, how CFA and FUG have managed conflicts in the past. It also helped to capture reported cases of conflicts over the years.

Patton (2002) points out that documents provide the researcher with information about things that cannot otherwise be observed or about which the researcher was unaware. They may uncover events that took place before the research began and have endured across time. They can also provide evidence that confirms or supports data gathered from other sources.

3.7.2 Semi-structured Interviews

(Appendix 5). This method offered participants the opportunity to explore issues of conflict in the era of decentralised forest management. The interviewees, were afforded a leeway to explore the subject in as much depth as they pleased (Longhurst, 2009). The method was also useful for collecting a range of opinions on the topic. Semi-structured, in-depth interviews were useful for investigating issues, which informants found difficult to discuss in a Focus Group Discussions (Appendix 4).

The semi structured interviews elicited data on types of conflicts (inter micro-micro; intra micro-micro, inter macro-micro, and intra macro-macro). They also captured data on decentralisation dynamics.

3.7.3 Observation

Proceedings of key CFA events were observed. In Upper Imenti, the Researcher observed two CFA meetings deliberating pertinent issues. In Nanyuki, the Researcher observed one CFA General meeting and CFA Elections. Non participant observation was used to capture data on groups’ conflict management strategies. All the information from observation was recorded through note taking and used to support the research objectives. The researcher also took photographs in the course of observation of the scenes that had relevant information to support the research objectives.

interpersonal interactions and organizational processes that were part of observable human experience (Patton, 2005).Observation served as a check against participants reporting in the household questionnaire and FGDs. The observations enhanced further probing during the interviews.

3.7.4 Household Questionnaires

A questionnaire is a method through which responses are gathered in a standardized way and therefore are more objective. In addition they are fast to administer thus, quick collection of information. The household questionnaire used in the study (Appendix 3) was divided into six sections each focusing on a different item. The questions adopted the Likert type items. This is because conflict is more of a perception and is best explained rather than quantified. Thus the tool allowed the respondents to freely express what they felt on this matter.

3.7.5 Focus Group Discussion (FGDs)

3.8 Instruments Validity and Reliability

The validity of a test is a measure of how well a test measures what it is supposed to measure (Kombo and Tromp, 2006). Pre-test for the household questionnaire was carried out in Kabaru Forest. The pre-test assisted in determining the accuracy of the tools. The pre-test involved 40 respondents from the Kabaru village in Nyeri. They constituted 10% of the total sample. The correlation coefficient was 0.89. Content validity was applied in this case. On the other hand, reliability enhances the dependability, accuracy and adequacy of the instruments. Mugenda and Mugenda, (1999) observe that reliability is a measure of degree to which a research instrument yields consistent results often on a repeated trial.

3.9 Data Analysis and Presentation

Interview data was analysed qualitatively with narrative correlation being used in corroborating the results with questionnaire and documents analysis. The patterns, themes and categories of analysis were not imposed prior to data analysis. This conforms to arguments by scholars such as Bowen (2005) and Coffey and Atkinson (1996). Focus Group Discussion data which was in the form of field notes was transcribed and typed into “ms-word”. Themes and sub-themes were created guided by the objectives of the study.

Critical reading of the data sources was done in order to pick out relevant information relating to the created themes and sub-themes. Cutting and pasting of relevant information into sub-themes was done. This information was later described to give meaning as per objectives of the study. The approach is supported by authorities in research such as Glaser and Strauss (1967) Glaser (1978) and Goulding, 1998). If a theme was identified from the data that did not fit the existing codes, a new code would be created. Open coding postulated by Strauss and Corbin (1998) was employed.

3.10 Ethical Considerations

According to Israel and Hay (2006) as cited by Creswell (2009), researchers need to protect respondents, develop a rapport with them, and promote the integrity of research. Ethical issues in this study were ensured by taking some deliberate actions as outlined by Miles and Huberman (1994). These are Informed consent; Harm and risk; Honesty and trust; Privacy, confidentiality, and anonymity; Intervention and advocacy. These issues were observed during data collection and analysis.

Informed consent: Respondents were informed of the purpose of the research as outlined in the Research Authorisation from Kenyatta University (Appendix 15), the Research Permit issued by the National Council for Science, Technology and Innovation (NACOSTI) (Appendix 16), and Permit from the KFS (Appendix 17). Interviews were conducted only after the interviewees agreed participate.

Researcher made appointments with interviewees and interviewed them at their convenient place and time. The researcher only took photographs after permission was granted by the interviewees.

There are respondents who asked for the final research report. These include KFS, KWS and the CFAs. A copy of the thesis will also go to National Commission for Science, Technology and Innovation (NACOSTI). Upon examination of the thesis, copies will be availed to them as agreed.

Permission to carry out the research was sought and granted by different relevant authorities. First, the Research Authorisation was given by the Graduate School of Kenyatta University (Appendix 15). Clearance was then sought and given by the National Commission for Science, Technology and Innovation (Appendix 16). Permission was also sought and granted from the Kenya Forest Service (Appendix 17).

CHAPTER FOUR: RESULTS AND DISCUSSION 4.1 Introduction

This chapter focuses on the results of the study and accompanying discussions. These are founded upon the data gathered using household questionnaires, key informant interviews, documents analysis, focus group discussions and field observations. The general objective of this study was to examine how conflict dynamics in Mount Kenya forest have been influenced by the implementation of decentralized forest management regime.

The results are presented in four sections aligned to the specific objectives of the study. These sections begin by showing demographic characteristics of respondents (gender, age, education level, residing distance from forest, membership to forest user groups and period of stay in the study area), types of stakeholder conflicts, decentralisation dynamics and the link to forest conflicts in Mount Kenya Forest and prevalence of the different conflict management approaches. Ultimately, the chapter discusses the results of the study on link of decentralisation to access, use and management of Mount Kenya Forest.

4.2 Socio-demographic Characteristics of the Respondents