Climate Change

and the Historic

Environment

May Cassar

... the spring, the summer,

The chiding autumn, angry winter, change Their wonted liveries, and the mazèd world By their increase, now knows not which is which: And this same progeny of evils comes

From our debate, from our dissension; We are their parents and original.’

A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Act II Scene I

Cover photograph © English Heritage: National Monuments Record. Ringbrough Coastal Battery, Humberside

Coastal erosion presents a major threat to many sites of 20th century archaeology. Built between 1941–2, this Coastal Artillery Battery which includes cast concrete munitions trackways and ancillary buildings is now in immediate threat of complete destruction.

Designed and typeset by Boldface Typesetters, London EC1 Printed by The Russell Press, Nottingham

ISBN 0-9544830-6-5

Published by the Centre for Sustainable Heritage, University College London with support from English Heritage and the UK Climate Impacts Programme

Copyright © 2005 UCL

All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without the written permission of the publishers, save in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency.

In 2002, the Centre for Sustainable Heritage was commissioned by English Heritage to carry out a scoping study on climate change and the historic environment, including buried archaeology, historic buildings, parks and gardens (Archaeology Commissions PNUM 3167). The start of the study coincided with the publication of the current UKCIP02 climate change scenarios. The final report has been prepared by Professor May Cassar, while the original research was carried out by Dr Robyn Pender. However, such a report is never the product of one or two individuals. There were numerous other collaborators in the study including Professor Bill Bordass (William Bordass Associates), Jane Corcoran (Museum of London Archaeology Service), Professor Lord Julian Hunt (UCL), Taryn Nixon (Museum of London Archaeology Service), Professor Tadj Oreszczyn (UCL) and Professor Phil Steadman (UCL). English Heritage’s interests were represented by Mike Corfield and latterly by Bill Martin. UKCIP through Dr.Richenda Connell provided scientific advice during the editing of the report. The study could never have been carried out without strong regional participation from heritage managers in the East of England and the North West of England as well as scientists and policy makers.

It is intended that this report will make a contribution to the debate on the impact of climate change on the historic environment. Its recommendations and the gaps in information and research that it has identified should be the focus of discussion and timely resolution.

31 August 2005

Table of contents

1. Key recommendations 1

2. Description of the English Heritage climate change scoping study 4

2.1 Context of the scoping study 4

2.2 Climate change prediction and policy 8

3. Sources of climate change information, advice, and research 11

3.1 Advice and research 11

3.2 Critical bibliography 12

3.3 Available information: conclusions 19

4. Determining heritage susceptibility to climate change 20

4.1 Questionnaire 21

4.2 Site visits 34

4.3 Regional workshops 37

4.4 Key factors determined by the scoping study 42

5. Demonstration maps of climate change vulnerability 44

5.1 Demonstration maps 45

6. Implications for policy 62

6.1 Policy-makers’ workshop 62

6.2 Conclusions 63

7. Gaps in information and research 65

7.1 Background 65

7.2 Short-term actions 65

7.3 Medium-term actions 66

Annex 1: Climate change questionnaire 68

List of respondents 86

Results of questionnaire 89

Annex 2: Site visits 91

Annex 3: Regional workshops 92

List of participants 92

Handouts for breakout sessions 93

Discussion wheels 96

Summary of results from breakout sessions 97

English Heritage in its annual report on the state of England’s historic environment Heritage Counts[www.heritagecounts.org.uk] acknowledges that ‘long-term climate change . . . threatens to impact upon all aspects of daily life, not least the survival of heritage assets’ (Heritage Counts 2004, 5.5 Environmental Sustain ability). This report provides essential background information necessary to address one of the key questions in the first State of the Historic Environment Review in 2002 namely, ‘identifying ways of measuring the impact of climate change and the historic environment’ (SHER02, Challenge 5).

Whether or not there is universal acceptance of the level of climate change impact described in this report, these recommendations deserve careful consideration because they are based on evidence of a fragile heritage which could be damaged by much less than a catastrophic event.

Recommendation 1:Sector leadership on climate change

English Heritage should maintain sector leadership on climate change it has established by commissioning this study, by leading on the development of climate change impact indicators, by disseminating information on climate change to historic environment stakeholders and by promoting the inclusion of climate change impact on the historic environment in wider agendas.

Recommendation 2:

Monitoring, management and maintenance

Climate change often highlights long standing preservation issues, rather than discovering new problems. The issue that English Heritage needs to address is how to streamline current monitoring, management and maintenance practices to improve the stability of the historic environment, no matter how weak or strong is the impact of climate change.

It is important that English Heritage promotes and supports local decision-making in maintenance and emergency response. To do this effectively, local cross-disciplinary training programmes in basic maintenance procedures for its own staff and contractors should be considered. Good maintenance could also be promoted by shifting the emphasis from grants for repair to grants for maintenance.

Key recommendations

Recommendation 3:

Value and significance in managing

climate change impacts

The ‘save all’ approach to the historic environment needs to be re-evaluated. It is not realistic to conserve anything forever or everything for any time at all. Conservation planning pioneered by English Heritage, stems from a consideration of value and significance of the historic environment. Value and significance have also been considered in the Designation Review which has looked at what is conserved and why, and the value of the commonplace. Value and significance must also be part of future planning of the historic environment faced by a changing and worsening climate. Both English Heritage and the National Trust are already facing up to difficult decisions on how to manage the coastal heritage in the face of sea level rise induced by climate change.

Recommendation 4:

Participation in the planning of other agencies

English Heritage needs to raise its profile outside the heritage sector by participating and contributing fully to the measures being developed by agencies responsible for addressing climate change impacts in other sectors such as the Environment Agency and the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra). English Heritage is in a strong position to do so because of its natural affinity with long-term planning.

Recommendation 5:

Fully functional heritage information system

There is an urgent need to overcome the weaknesses of paper maps and disparate databases and to transform all existing information to a single standard. A fully functioning and fully integrated heritage information system should replace individual project mapping with a comprehensive digital map base that integrates currently separate data-sets and links them to images such as photographs and plans. It should also be able to capture, display and analyse heritage data in context with other geographic data and appropriate information from climate change models. It should have the capability of continuous upgrading and refinement and be available as an on-line facility.

Recommendation 6:

Emergency preparedness

government, and staffed largely by trained volunteers, one of their key functions is the immediate protection of storm-damaged property to reduce the risk of further damage. With extreme weather being predicted for the UK, and with the major storms of 1990, 1998 and 2000 in the UK, costing the insurance industry in excess of £3 billion (data source: Ecclesiastical Insurance Group), English Heritage and other heritage organisations together with the Environment Agency should lead on the establishment of a similar service.

Recommendation 7:

Adaptation strategies and guidelines for

historic buildings, archaeology, parks and gardens

There is little published on conservation and directed adaptation of the historic environment in response to climate change. This is an important gap that English Heritage should aim to fill. This process can begin by integrating climate change impacts in the revision of English Heritage’s ‘Practical Conservation’ series, making use of the results from recent research such as the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC)/United Kingdom Climate Impacts Programme (UKCIP) Engineering His toric Futures project [www.ucl.ac.uk/sustainableheritage/research/Historic Futures/] and the EC project on Global Climate Change Impact on Built Heritage and Cultural Landscapes (Noah’s Ark)(http://noahsark.isac. cnr.it/). An important focus of attention should be adaptation of drainage and rainwater goods, and the discreet provision of irrigation and water storage. The latter makes sense in any circumstances, as too much water is being drawn from aquifers and groundwater sources. Opportunities should be identified to roll out and integrate these issues into existing or planned projects in buildings, archaeology, parks and gardens.

Recommendation 8:

Buried archaeology and prediction maps

‘Climate change is an acknowledged threat to both the natural and the historic environment. For example, changes in the intensity and frequency of storm events will pose a challenge to a wide spectrum of the historic environment from coastal sites to veteran trees. Can we measure the likely impact and cost the necessary mitigation?’

State of the Historic Environment Report, English Heritage, 2002.

English Heritage, recognising the need for information about the likely impact of climate change on the historic environment of the

UK, commissioned University College London (Centre for Sustainable Heritage) to produce a scoping study designed to investigate likely risks and suitable strategies of mitigation and adaptation. This is the report of that study.

2.1

Context of the scoping study

Introduction

Climate change has been a much-debated issue for some years, but it is now widely accepted that well-established climate patterns are indeed changing. It is becoming a matter of urgency not only to mitigate the level of future change by reducing greenhouse gas emissions, but also to develop plans to adapt our societies and economies to cope with the climate changes that will occur.

The Third Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [IPCC] – the UN’s scientific advisory committee on climate change effects – notes: ‘Adaptation has the potential to reduce adverse effects of climate change and can often produce immediate ancillary benefits, but will not prevent all damages.’ [p.12] They further observe that ‘ . . . well-founded actions to adapt to... climate change are more effective, and in some circumstances may be cheaper, if taken earlier rather than later.’ [p18] Even so, it has proved difficult to convince many planners of the need to incorporate climate change into their strategies. For this there appear to be two main reasons: firstly a time-scale much longer than most planning horizons, and thus seemingly less urgent, and secondly the uncertainty implicit in climate predictions.

Description of the English Heritage

climate change scoping study

Predictions must incorporate not only the scientific uncertainties inherent in trying to model complex weather systems, but also the much less quantifiable uncertainties in future emissions, and so the temptation arises to ‘wait until the situation is certain.’

There is, however, one sector that operates on long term planning, and for which the climate instability has particularly serious implications: the historic environ ment. Dealing day-to-day with the conservation of sites that may be thousands of years old makes heritage managers see problems 50 or 80 years hence (as given in the UK Climate Impact Programme (UKCIP)’s pub lished climate change scenarios and in Table 1) as a current issue. They are well aware, too, of the complex inter action between their sites and the local climate, and con cerned about any forces which may disrupt equilibrium conditions under which the sites have been preserved for so long.

It is therefore not surprising that heritage organisa tions in the UK have been active in trying to assess the impacts of climate change which will need to be integrated into their planning. The National Trust, for example, has been actively considering future policy in this light since the mid 1990s. English Heritage com -missioned this broad-based scoping study to look at the impacts of climate change on the historic environment, and propose strategies for adapting to the new risks and problems, and it has also proposed a policy on climate change (March 2005).

Specification for the scoping study

Old buildings, archaeological sites, and historic parks and gardens are put at risk by the same dangers to the wider environment – flooding, coastal erosion, subsidence and possibly increased storminess – which have already been identified by other climate change studies. However, they present in addition a number of complexities that suggest they may be especially imperiled.

Changes in rainfall patterns and temperatures, even where these may not be perceived as a major threat to modern buildings, are likely to have dramatic effects on

‘Global temperature has risen by about 0.6˚C over the last 100 years, and 1998 was the single warmest year in the 142-year global instrumental record . . . The UK climate has also changed over the same period, and many of these changes are consistent with the warming of global climate. . . . Much of the change in climate over the next 30 to 40 years has already been determined by historic emissions and because of the inertia in the climate system. We are likely, therefore, to have to adapt to some degree of climate change however much future emissions are reduced.’

buried or exposed archaeological sites. Parks, gardens and historic landscapes will be faced not only with changed climates, but very possibly with shortages of water and other resources that could make maintenance increasingly troublesome. It may become difficult to propagate even endemic species. For old buildings and their preserved contents the problems are also likely to prove acute; it has long been understood that fluctuations in the local microclimate present the main danger to continued survival. Historic building materials are extremely permeable to the environment of air and soil; changes in moisture content can occur rapidly, and these can activate damaging cycles of salt crystallisation. Old rainwater goods may be unable to cope with changed patterns of rainfall, and acute events such as flooding have much worse and longer-term effects on historic than on modern buildings.

Expensive protection and adaptation strategies may be necessary to cope with these greatly increased dangers, and these will therefore require careful planning based on a controlled assessment of risk.

Methodology

In response to English Heritage’s brief for scoping the likely impacts of climate change on the historic environment, the Centre for Sustainable Heritage at University College London has used a diverse range of information sources. Climate change and adaptation literature together with expert views from climate and heritage specialists were reviewed and assessed. A detailed questionnaire gathered responses from man agers and advisers in organisations including English Heritage and the National Trust, as well as from field officers, and from local authority officers responsible for archaeology and listed properties. Current views, future plans and possible conflicts of interest between different aspects of the historic environment were elaborated during regional meetings which focussed on prioritising issues as well as gathering expert views. Information was also gathered from local managers and field officers during a number of site visits. Finally a work shop for policy makers was presented with the results. This meeting successfully distilled a

‘Climate change decision making is essentially a sequential process under general uncertainty. Decision making has to deal with uncertainties including the risk of nonlinear and/or irreversible changes, entails

balancing the risks of either

insufficient or excessive action, and involves careful consideration of the consequences (both environmental and economic), their likelihood, and society’s attitude towards risk.’

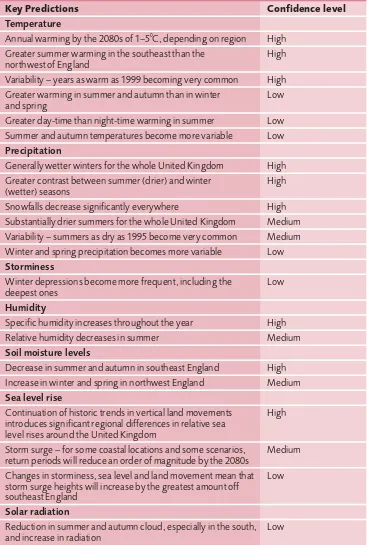

Table 1: Projections from the UKCIP02 climate change scenarios

showing relative confidence levels (H = high; M = medium; L = low)

Key Predictions Confidence level

Temperature

Annual warming by the 2080s of 1–50

C, depending on region High Greater summer warming in the southeast than the High northwest of England

Variability – years as warm as 1999 becoming very common High Greater warming in summer and autumn than in winter Low and spring

Greater day-time than night-time warming in summer Low Summer and autumn temperatures become more variable Low

Precipitation

Generally wetter winters for the whole United Kingdom High Greater contrast between summer (drier) and winter High (wetter) seasons

Snowfalls decrease significantly everywhere High

Substantially drier summers for the whole United Kingdom Medium Variability – summers as dry as 1995 become very common Medium Winter and spring precipitation becomes more variable Low

Storminess

Winter depressions become more frequent, including the Low deepest ones

Humidity

Specific humidity increases throughout the year High

Relative humidity decreases in summer Medium

Soil moisture levels

Decrease in summer and autumn in southeast England High Increase in winter and spring in northwest England Medium

Sea level rise

Continuation of historic trends in vertical land movements High introduces significant regional differences in relative sea

level rises around the United Kingdom

Storm surge – for some coastal locations and some scenarios, Medium return periods will reduce an order of magnitude by the 2080s

Changes in storminess, sea level and land movement mean that Low storm surge heights will increase by the greatest amount off

southeast England

Solar radiation

number of important recommendations, as well as producing some general directions for adapting the historic environment to a changing climate.

This integrated and broad methodology was made feasible by concentrating the study on the risks to cultural heritage in two English regions: the East of England and North West of England. These were chosen to coincide with the areas already studied by Cranfield University’s ‘Regional Climate Change Impact Response Studies in East of England and North West England’ (RegIS) project (from which information is already available) and to provide contrasts in crucial factors such as flood risk, accessibility and urbanisation, climate, and type of buildings, archaeology, and gardens.

The study tried to scope useful ways of assessing and adapting to possibly unpredictable climate change risks. This report details these suggestions and sup -port ing information. It includes a number of demonstration risk maps for the East of England and the North West, which are presented to compare the susceptibility of local heritage sites to the patterns of climate change projected by Regional Climate Models for the UK. The report also clearly identifies future areas of research and the policy implications to meet the needs of cultural heritage in a changing climate.

2.2

Climate change prediction and policy

Modelling future climates

Climate predictions are based on climate models, which in turn are constructed from studies of the current climate system, and the factors which influence it. The UK Meteorological Office [Met Office] defines the climate system as shown below.

such Regional Climate Models (RCMs). The projections on which this Scoping Study is based are taken from the output of HadRM3, available through the Climate Impacts LINK Project [www.cru.uea.ac.uk/link/] and published by UK Climate Impacts Programme [UKCIP] [www.ukcip.org.uk/]. Resolution for the projections released in 2002 is 50 km over Europe, with the model run over the periods 1961-90 and 2070-99 for a range of emissions scenarios. Refinement of global models is ongoing and the next set of UKCIP scenarios will be published in 2007/08.

Using climate models to plan ahead

Having such a state-of-the-art tool as the 2002 regional predictions from HadRM3 allows initial responses to the threat of climate change to take place, and set in motion long-term adaptation processes. It is not only important for heritage managers to decide their own response: statutory bodies such as the Environment Agency are also using these new tools to plan ahead, and – since plans such as flood defences crucially impact on the historic environment – it is important that a considered heritage response is developed and communicated across public decision-making as an integrated response will be ultimately more effective at safeguarding against damage.

The willingness of heritage managers to plan ahead could see them emerge as leaders: they have direct access to the general public through their work, and could help to articulate concerns over loss to what is historically significant from climate change. Knowledge of past climatic variations and their impacts on the environment and on human activities may help to guide planning of responses to future climate changes. The following is an assessment of the issues of

particular concern to the historic environment which arise out of climate change. Many potential problems have been identified, and indeed there are few aspects of con ser va -tion and preserva-tion practices that will not be affected by future changes. This Scoping Study also questions our attitude to the historic environ ment and our approach to its conservation and preservation and the priority that should be given to climate change adaptation.

‘ . . . well-founded actions to adapt to climate change are more effective, and in some circumstances may be cheaper, if taken earlier rather than later.’

Sources of climate change

information, advice and research

3

There is an overwhelming amount of information available: in print, in electronic format, and as advice from different organisations. Some is frequently updated, so it is almost impossible to dip into the information and obtain a quick snapshot of developments. Consequently in sourcing information for this report, rather than attempting to be comprehensive, the aim has been to clearly identify the key sources of information and advice, and to create a guide to the most generally important and useful information.

3.1

Advice and research

The organisations undertaking these activities can be conveniently grouped under two headings: global and UK-focused.

The single most important global organisation is the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [IPCC], ‘established by the World Meteorological Organization [WMO] and the United Nations Environment Programme [UNEP] to assess scientific, technical and socioeconomic information relevant for the understanding of climate change, its potential impacts and options for adaptation and mitigation’.

its impact on humanity; the course and causes of climate change during the present century and prospects for the future’, and the Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research which intends ‘to develop sustainable responses to climate change through trans-disciplinary research and dialogue on both a national and international level’.

3.2

Critical bibliography

The following is a guide to some of the most useful literature and other information sources currently available. It includes web-based guidance and data as well as publications, as much of use appears in this form. This literature can be roughly divided into three categories, which are: Climate Systems, Approaches to Mitigation, and Impact/Adaptation Studies. Most literature considers all three, but as a rule tends to emphasise one theme, with the other categories being given secondary consideration. In the following discussion, literature is classed by its category of main reference, and within this it is grouped by whether the primary scope of the study is global/international, UK, sectoral, or regional/local.

䡵Climate Systems

These include studies that address the evidence for and mechanics of climate change, the climate and social models (scenarios) that underlie predictions of future climate, and studies presenting the predictions generated by such models. Since climate systems are studied at a global / international and national levels, and not at a sectoral or regional / local level, the literature originates from these sources.

䡵Global/International Reports

● It presents in a straightforward and easy-to-consult manner the background to climate change prediction.

● It provides an excellent summary of the meaning and development of futures scenarios and the global view of chance, mitigation, and adaptation.

● It discusses the assumptions and boundary conditions of the various climate models.

● It compares the results of different models.

This publication can be consulted online at [www.ipcc.ch/pub/SYRspm.pdf] (Policy-Makers Summary). The four volumes are available at [www.ipcc.ch/pub/ SYRtechsum.pdf].

The IPCC regularly publishes proceedings of workshops on the latest developments in climate science [www.ipcc.ch/pub/pub.htm]. For example, a workshop in 2002 discussed the best approaches to predicting extreme weather events [www.ipcc.ch/pub/extremes.pdf]. The proceedings note that small-scale climate events have associated high costs: ‘In one important example, land subsidence losses from two droughts during the 1990s in France resulted in losses of US$2.5 billion – a cost on a par with large hurricanes. Subsidence losses have been observed to triple during drought years in the UK, with a cost approaching $1 billion annually.’ The IPCC Fourth Assessment Report is due for publication in 2007.

There are a number of internationally recognised climate modelling centres and the results of their work can be obtained through the IPCC Data Distribution Centre [http://ipcc-ddc.cru.uea.ac.uk/].

䡵National Reports

At a national level, the most important tool for future planning in the UK is the UKCIP02 climate change scenarios presented in ‘Climate Change Scenarios for the United Kingdom: The UKCIP02 Scientific Report’ [UKCIP02] [www.ukcip.org.uk/]. This report provides some of the data generated by the Hadley Centre’s Regional Climate Model, HadRM3, as 26 parameters of monthly data on a 50km grid. The full set of data can be obtained directly from UKCIP.

of future temperature and rainfall can be calculated by adding these changes to the UKCIP02 baseline dataset. UKCIP02 includes details of seasonal average changes and some information on changes in extreme events though this is less robust. This report gives the ‘best guesses’ for future UK climate predictions in an accessible way.

䡵Approaches to climate change mitigation

In climate change science, ‘mitigation’ is given a very precise meaning: the limiting of the scale of future climate change by addressing greenhouse gas emissions (this strict meaning is used throughout this report, to prevent confusion). Mitigation lies largely within the political/industrial sphere, as it deals with preventive measures on a geopolitical level. The purpose of this study was to scope the current and future impact on the historic environment of the climate change which is already taking place. The topic of climate change mitigation lies therefore outside this study and is not covered in this report.

䡵Impact/Adaptation Studies

This category includes both literature that addresses the implications of climate change, and that which discusses the economic, social and practical measures that will be needed in response.

The study addressed the predictions for climate change in the UK and how specifically management of the historic environment needs to be adapted in response; this report therefore does not discuss detailed measures. Nevertheless, it is perhaps useful to note that much information can be found throughout the recommended impact/adaptation reading material.

䡵Global/International Reports

䡵National Reports

Nationally, Defra is the UK Government Department responsible for the official UK response to its climate change treaty commit ments. It regularly publishes ‘National Commu nications’ the latest being ‘The UK’s Third National Communication under the Framework Convention on Climate Change’ [www.defra.gov.uk/ environment/climatechange/3nc/pdf/climate_3nc. pdf]. Defra has also published ‘The Impacts of Climate Change: Implications for Defra’ [www.defra.gov.uk/ environment/climatechange/impacts2/index.htm] which sets out the policy challenges the department faces in response to climate change.

For a useful synopses of all the research conducted under the umbrella of the UKCIP see ‘Measuring progress: Preparing for climate change through the UK Climate Impacts Programme’ [www.ukcip.org.uk/].

The publication by Defra’s predecessor, MAFF of ‘Flood and Coastal Defence Project Appraisal Guidance’, addresses coastal flooding and loss and the likelihood of adaptation strategies endangering the historic environment [www.defra.gov.uk/ environ/fcd/pubs/pagn/fcdpag1.pdf]. This makes it a critical reference document for English Heritage’s input into the crucial area of coastal planning. More recently the Government’s Foresight Programme has published the ‘Future Flooding’ report which assesses the change in flood risk caused by climate change and socio-economic change over the 21st century [http://www.foresight.gov.uk/previous_projects/ flood_and_coastal_defence/ index.html].

The Environment Agency’s publications are usually published online. The Agency has devised a programme of research aimed at incorporating climate change considerations within policy, processes and regulations. Jointly with Defra, it runs a research programme focusing on flood management [www.defra.gov.uk/environ/ fcd/research/].

UKCIP’s ‘Climate Change and Local Communities – How prepared are you?’ [www.ukcip.org.uk/] and the Environment Agency’s ‘The climate is changing: time to get ready’ [www.environment-agency.gov.uk/] though useful, are less strategically important than the above.

‘We believe that further research on climate change impacts is needed but that work on adaptation should not wait until such research is complete, given that many of the options will have a positive impact

regardless of climate considerations and are worth doing anyway.’

䡵Sectoral Reports

A number of published sectoral reports are useful to highlight for different reasons: some provide useful information in their own right; others will provide English Heritage with useful examples of how other sectors are responding to climate change impacts. The reports most worthy of note are discussed in some detail below.

The EPSRC and UKCIP are supporting a portfolio of projects, which will produce reports under the banner ‘Building knowledge for a changing climate’ (BKCC). The projects which include Engineering Historic Futures(page 3) and Betwixt(page 45) are investigating the impacts of climate change on the built environment, transport and utilities, including historic buildings, urban planning, urban drainage and slope stability [www.ukcip.org.uk].

The Construction Research and Innovation Strategy Panel (CRISP) has produced a report ‘CRISP Consultancy Commission 01/04, A Review of Recent and Current Initiatives on Climate Change and its Impact on the Built Environment: Impact, Effective -ness and Recommendations’ containing a very useful critical review of various climate change initiatives and programmes.

The Foundation for the Built Environment published a report ‘Potential Implications of Climate Change in the Built Environment’ (Graves H M and Phillipson M C, 2000, ISBN 1 86081 447 6) which contains technical assessments of potential impacts and adaptation strategies based on the UKCIP98 scenarios. Though these have been superseded by the UKCIP02 scenarios the results still stand.

The Construction Industry Research and Information Association (CIRIA) has published a review of the implications of climate change and practical guidance on assessing and managing the associated risks, such as ground movement, rain penetra -tion and wind loading. ‘Climate change risks in building – an introduc-tion (C638)’ can be obtained from CIRIA [http://www.ciria.org/acatalog/C638.html].

The Chartered Institution of Building Services Engineers (CIBSE) has published ‘Climate Change and the Indoor Environment: Impacts and Adaptation’ (CIBSE TM36: 2005) which provides building simulation case studies including one on a 19th century semi-detached house with suggested adaptation to avoid overheating.

The RegIS report was the basis for selecting the East of England and the North West for detailed regional examination in this study [www.ukcip.org.uk/]. It provides an integrated assessment of climate impacts on agriculture, biodiversity, water resources and the coastal zone.

The MONARCH report ‘Climate Change and Nature Conservation in Britain and Ireland: Modelling natural resource responses to climate change (the MONARCH project)’ focuses on biodiversity impacts [www.ukcip.org.uk/].

The National Trust has taken the lead on climate change impacts in a number of areas. The web-based ‘National Trust Climate Change: A Paper presented by the Head of Nature Conservation and the Environmental Practices Adviser on behalf of the Chief Agent’ is the Trust’s foundation document on its response to Climate Change [www.nationaltrust.org.uk/environment/html/env_iss/papers/envissu2.htm]. ‘The National Trust Soil Policy’ was the first of its kind; it presents the National Trust’s approach to climate change issues and as such is an important publication [www. nationaltrust.org.uk/environment/html/env_iss/pdf/soil01.pdf]. The ‘National Trust PPS14: Climate Change’ is the National Trust’s relevant Planning Position Statement [www.nationaltrust.org.uk/environment/html/land_use/pdf/pps14.pdf]. The National Trust has recently undertaken a coastal risk assessment for the next 100 years [http://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/coastline/save/coastal_policy.html].

The National Trust was also the major contributor to a study by Reading University, published recently by UKCIP titled ‘Gardening in the Global Greenhouse: The Impacts of Climate Change on Gardens in the UK’ [www.ukcip.org.uk/].

[Eds. B. Coles and A. Olivier, EAC 2001]. The proceedings of the two national con fer -ences on Preserving Archaeological Remains in Situ (1996, 2001) – jointly organised by English Heritage and the Museum of London Archaeology Service [MoLAS] – are noteworthy. [MoLAS, 1998 (ISBN 901992-02-0) and MoLAS, 2004 (ISBN 1-901992-36-5)] These conferences sought to identify strategies for under standing the physical, chemical, and biological environment of buried archaeology. This is the necessary foundation for comprehending the potential impacts of climate change.

The Country Land & Business Association’s ‘Climate Change and the Rural Economy’ published in 2001 is a very focused report, with a useful Executive Summary [www.cla.org.uk].

䡵Reports from the English regions and devolved governments of the UK

All the English regions as well as Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland (Table 2) have carried out scoping studies and published reports on the impact of climate change. These can be found on the UKCIP website at www.ukcip.org.uk.

Table 2 Summaries of scoping study reports produced by the English regions and

devolved governments of the United Kingdom

Location Scoping study report

South West Warming to the idea: Meeting the challenge of climate change in the South West South East Rising to the challenge: The impacts of climate change in the South East

London London’s warming. The impacts of climate change on London East of England Living with climate change in the East of England

East Midlands The potential impacts of climate change in the East Midlands West Midlands The potential impacts of climate change in the West Midlands

North West Changing by degrees – The impacts of climate change in the North West

Yorkshire & Humber Warming up the region: The impacts of climate change in the Yorkshire and Humber Region

North East And the weather today is …

Scotland Climate change: Scottish implications scoping study

Northern Ireland Implications of climate change for Northern Ireland: informing strategy development Wales Wales: Changing climate, challenging choices: the impacts of climate change in Wales

3.3

Available information: conclusions

Excellent information is now available on the background to climate change, especially through IPCC and UKCIP. A good range of policy-makers’ advice exists on general issues, but there are very few guidelines on directed adaptation.

There is little published on preservation of the historic environment and climate change impact. This is a task in which English Heritage could lead. Climate change often highlights long standing preservation issues rather than creating new problems. The fundamental issue that needs to be addressed by everyone is how to streamline current management and maintenance practices, which will improve the historic environment whether or not the impact of climate change proves as severe as predicted under the worst case scenarios.

‘The Trust is presently concerned with many aspects of environmental change, such as land use, agriculture, transport and water resources. The Trust will need to

understand the short and long term

interrelationships between these issues and climate change issues; and may have to adjust conservation practices to account for different types and rates of change than have previously been experienced.’

Of the many predicted changes to the UK climate, which are likely to be of greatest importance to preserving the historic environment? To determine this central question of the Scoping Study, the methodology described below was devised:

● Establish climate-related factors of concern– In consultation with the project team, the widest possible list of likely climate-related problems for the preservation of the historic environment was drawn up.

● Establish impact of climate change on these factors– The 2080s predictions of UKCIP02 and other sources were used to establish the likely climate change effects on these problematic factors, for the study areas of the East of England and the North West.

● Design questionnaire – This information was refined into text form, and incorporated into a questionnaire. This was then disseminated to a wide crosssection of heritage professionals – including local council officers – again concen -trating on (though not restricted to) the areas of the East of England and the North West.

● Site visits– Buildings, archaeological sites, and parks and gardens were visited and area managers, advisers, and field officers asked to comment on the climate change predictions.

● Regional workshops – The results of the questionnaire and site visits were compiled and presented at a Regional Workshop in each of the study areas.

● List of factors of concern refined– On the basis of the questionnaire results and the discussions held at the Regional Workshops, the original list of climate-related problems was refined to five issues central to the historic environment.

● Policy-makers' workshop – These issues were presented at a Policy-Makers' Workshop for detailed discussion and prioritisation.

● Report to English Heritage

Each of these steps is discussed in detail in the following sections.

Determining heritage susceptibility

to climate change

4.1

Questionnaire

A central part of the scoping study was a questionnaire designed to determine the level of concern felt about climate change by heritage managers (managers, field workers, local council advisers, and researchers). It was recognised, however, that questionnaires can easily lose focus, or become too difficult for busy respondents to complete satisfactorily; for this reason both the approach and the format of the questionnaire were designed in a very different way to, for example, those disseminated for the CRISP and National Trust Gardens studies.

In the report ‘The Impact of Climate Change: Implications for the DETR’ carried out by In-House Policy Consulting, Thomson noted a gap between climate change prediction, and its translation into practical guidance to help shape policy development and operational management. Talking with heritage managers during the design of the questionnaire, it became clear that this gap persists despite the efforts of UKCIP in publishing the recent scenarios. While this raises a side issue of how to attract media attention to important releases of information such as the UKCIP02 projections, the central problem remains that the exact data needed by individual planners is often difficult to extract from published data without considerable time and effort. This may be a result of publications being designed to appeal to a broad audience: there can be no single clear message.

It was clear that this questionnaire could be designed to serve also as an information document for heritage workers, thereby encouraging more focused and less generalised responses.

The questionnaire, the list of respondents and the results can be found in Annex 1. The following is a synopsis of the responses.

䡵Questionnaire results

Respondents were given a wide choice of planning time frames for future protection of the historic environment from which to select, from 0–5 years to greater than 100 years. Most ticked this latter option (Figure 1), even if they also noted that their budget horizons were much shorter. Repeatedly, respondents commented on the obligation to preserve for future generations.

䡵Buildings and Contents Rainfall

The greatest concern for respondents from the buildings sector was the predicted increases in heavy rainfall. ‘This is a huge concern as much damage is already due to faulty or inadequate water disposal systems, and many of the historic rainwater goods are not capable of handling heavy rains, and are often difficult to access, maintain, and adjust.’ It was noted that, although often rainwater goods have been over-designed, close monitoring would be needed to ensure that they were successfully coping with the changing climate.

This raises the problem of how rainwater disposal systems might be adjusted on listed buildings. ‘It may be difficult to increase the number or diameter of down pipes in order to cope with increased or heavier rainfall, because of the effect on the appearance of the buildings. Some buildings already have inadequate rain -water disposal systems, and we will have to look at unobtrusive ways of improving them.’ ‘Since dispersed water drainage systems in most rural historic buildings are very badly designed and poorly understood by their specifiers, a rush to redesign them could be harmful both to the buildings and the archaeology.’

Almost every respondent flagged the need

Figure 1: Heritage managers’ questionnaire responses on planning time-scales 25 20 15 10 5 0

0-5 6-10 11-25 26-50 51-100 >100 in years

for thorough maintenance: ‘Our experience is that most water ingress is due to lack of maintenance (for example blocked gullies and downpipes) rather than failure of materials.’

Flooding and soil moisture content

Fluvial flooding was identified as a major problem, requiring directed repairs and upgrading to drainage (it was noted that this has important implications for any surrounding archaeology). It was felt to be of great importance that disaster plans were reassessed and upgraded to cope with flood risks. Post-flood drying is critical, with buildings and excavated archaeology at great risk from subsidence.

Ground heave and subsidence as water recedes were identified as the major issues arising from projected changes in the water table height.

Coastal flooding and storm surge were also identified as extremely worrying, at least for sites in high-risk areas. ‘Storm surges are likely to have same effect as overall sea level rise, i.e. inexorable.’

It was in the context of the irrevocable and dramatic loss of coastal sites that one particular conservation theme raised by this study first arose: ‘We'll never save everything, so hard decisions are needed as to which to “let go”’. Coastal loss also raised the issue of heritage input into broader planning: ...I presume that major sea level rises will be a non-heritage issue (i.e. of such wider concern that it will be dealt with by other authorities).’

Extreme weather

The level of anxiety expressed over high winds by building respondents is the only case where the questionnaire results proved quite different from those arising from other aspects of the study, such as the site visits and the regional meetings, with only 17% expressing ‘great concern’. By contrast, direct discussions flagged this as a climate change issue of major importance, with wider ramifications for general emergency planning. Problem areas noted by questionnaire respondents include windows as well as roofs, awnings and verandas, and large trees close to buildings. Ruined buildings and excavated archaeology in particular would be in great danger of wind throw, indicating that more careful thought may have to be given to the stabilisation of such sites.

reveal any problems with maintenance: ‘Increased frequency of building inspections and attention to repair of defects in roof coverings will be increasingly essential.’

Temperature and relative humidity

The projected temperature changes were felt to be of most importance for visitor comfort; although winter heating would decrease, it was expected that there would be a corresponding push to install air-conditioning and cooling systems in summer. This should encourage further research into the environmental behaviour of traditional constructions and the design of passive systems including natural ventilation systems.

Rising temperature was also observed to be a risk for deterioration of materials and contents, since it would increase the rate of chemical reactions.

The outcome of changes in relative humidity was felt to be unpredictable, and therefore requiring of close monitoring. ‘The size and rate of fluctuations in relative humidity are at least as important as the mean levels, and it is hard to know how these may be affected. Since climate change is a gradual process, it is hoped that vulnerable materials will accommodate to these changes.’ ‘Broadly, this may be an improve -ment . . . However, the issue is the transition from current to future values and the re-equilibration of the porous materials. I think it would be folly to try to reproduce 'past' conditions by humidification etc. Rather, undertake the necessary monitoring and remedial interventions to make the [object] safe under the new prevailing conditions.’ However, it should be noted that ‘if the wet gets wetter and the dry drier, then both the absolute levels and the fluctuations could be more damaging,’ Humidity may rise problematically after intense rainfalls. As one correspondent noted that for efficient monitoring it will be necessary to establish clear standards and protocols for measuring and recording, and a set of baseline values.

Pests and diseases

Human comfort, health and safety

Human comfort, health and safety issues would have implications for climate control: ‘We would resist the introduction of intrusive climate control equipment, preferring if possible to use passive or minimally intrusive methods.’ Meticulous maintenance was again flagged as obligatory, to prevent dangers such as falling masonry.

Water table chemistry

If changes in water table chemistry result from a fall in water table height, or from sea-water incursion, certain areas may see a change in the pattern of damage from rising damp. Monitoring was felt to be a necessity, especially for sites already known to suffer from rising damp problems.

Solar radiation

Some concern was expressed for the impact of increased solar radiation on contents (rather than on the buildings themselves). It was however generally believed that current practices should be sufficient to cope, with relatively few refinements. ‘We are already investigating neutral density window films for light control, and introducing shutters and blinds even where there is no historical precedent.’ One correspondent noted that the introduction of filters does require an increased commitment to maintenance. ‘Sometimes excessive damp (e.g. from driving rain) followed by solar radiation can drive moisture and salts to the inside of walls. The incidence of this type of thing could be increased in climates which are warmer, damper and/or windier.’

Lightning

Lightning risk was another area where respondents felt current practice was probably adequate: ‘Efficient lightning conductors and fire precautions are already a priority.’

Plant physiology and distribution

Changes in plant physiology and distribution were of limited concern, except where plant roots may cause damage to foundations leading to subsidence of the whole

‘Climate control will be very problematic, as there is often a great rift between the needs of the occupant and the best interest of the fabric. Also, historic systems

structure. However, one correspondent noted that ‘the use of vegetation as a means of addressing the other conditions (such as wind or sunlight exposure) could be an interesting new consideration.’

䡵Buried Archaeology

Soil chemistry and moisture content

Unanimously, archaeologists expressed their great concern for soil moisture and due chemistry due to the projected changes in equilibrium conditions which have preserved the sites until now.

For wetlands sites, archaeologists are expecting ‘a very serious loss of certain data types which are only preserved in waterlogged/anaerobic/anoxic conditions.’ ‘Archaeology presently preserved close to the ground surface (i.e. especially in rural areas, or post-medieval archaeology in more urban situations) is likely to be destroyed before it is excavated and recorded.’

Drying of the soil has indirect effects on the archaeological record as well: ‘Sites will lose stratigraphic integrity if they crack and heave due to changes in sediment moisture.’ ‘Strong changes between water levels for summers and winters will have a tremendous effect on those sites which are situated in the area of dry-wet cycles.’

Repeatedly, respondents noted a significant gap in knowledge: the exact effects of chemical changes on preservation are poorly understood. ‘We do not know much about how chemicals affect artefacts in the plough soil which is a matter of great interest to those who identify and record portable antiquities.’ ‘Eutrophication could accelerate microbial decomposition of organics, and might also influence corrosion of metals.’ ‘We have little data on nitrates and artefact corrosion... further research is required.’

Flooding

Many sites will be endangered by sea level rise and storm surge: ‘600 to 1800 good sites are vulnerable to coastal erosion.’ Although this threat is already recognised – and, indeed, already active in many places – management practices do not yet take sufficient account of the problem: ‘Flood protection/ managed retreat plans tend to consider only scheduled ancient

monuments, although we are trying to change this attitude to include other archaeological sites, including those below the current low tide level...’ Inevitable loss will probably require approaches to rapid investigation and recording.

Here too, the issues of chemical disturbance were of concern: ‘Coastal floods will introduce intermittently large masses of ‘strange’ water to the site, which may disturb the metastable equilibrium between artefacts and soil.’ Not all sites will be endangered as a matter of course: ‘Some Fenland rivers are already under tidal influence. Many prehistoric and Roman fenland sites were built and decayed in salt-rich environments.’

Some of the effects on archaeology are likely to be indirect. Buried archaeology may be at risk not only from flooding but also from ill-considered flood risk alleviation schemes.

The predicted changes in rainfall are also likely to cause flooding, and associated erosion. Again, it was felt that many sites would inevitably be lost: ‘River side/intertidal archaeology will have to be recorded – this sort of thing cannot be protected in such large tracts of land/river.’ Erosion could be slowed down, it was noted, by appropriate planting.

Plant physiology and distribution

Plant physiology and distribution changes were also a cause for concern. ‘Changes in vegetation cover will greatly affect the survival of buried sediments and artefacts and ecofacts. Deep root penetration is very damaging to structures and sediment boundaries.’ There is also the problem of dewatering by transpiration, and loss of vegetation cover through drought could also exacerbate erosion. Here the issue of mitigation came up briefly: ‘New energy crops (e.g. shortcycle coppice and Mis -canthus) may be planted over sites.’

Human comfort, health and safety

Of the three heritage categories, it was archaeologists who expressed the greatest concerns over the possible health and safety issues raised by climate change. ‘Archaeological excavation and survey is often very arduous. More extreme conditions would only make them more so for fieldworkers.’ The actual conditions for

excavation were unlikely to be improved: ‘harder, drier ground, increased sun, heat and insects will all make the job more difficult, uncomfortable and risky.’ ‘Piped water will be required to make excavation/recording of archaeological sites possible.’

Temperature

Fears were expressed that increased temperatures will exacerbate deterioration. However, as one respondent noted, ‘seasonal changes in deposit temperatures are detectable. This must have some effect on bio-activity, but is probably not a limiting factor for decomposition.’ One respondent noted a possible advantage: an increase in crop marks.

Wind

The effects of high wind on buried archaeology were generally felt to be restricted to barrows, and sites in very dry or sandy subsoil conditions with the exception that tree throw could cause damage to archaeological sites in woodland or plantations. One correspondent noted that wind was another factor increasing the risk and expense of excavation.

Pests and diseases

Increased pests and diseases could disturb wetland sites in particular, ‘and we are very ignorant about long term effects.’

Other factors

Little concern was expressed for other climate changes. Increased solar radiation was felt unlikely to cause problems for buried material, although exposed material – especially painted surfaces – could be at risk. Solar radiation could certainly help desiccate uncovered soil.

䡵Parks, Gardens and Landscapes Wind

designs, and the changes in climate may make replacement difficult or impossible. Since the gale of 1987, this has been an action issue for gardeners: ‘Shelter belt redesign is being considered in places (though the land acquisition required to extend belts will give rise to costs).’

Temperature

The predicted changes in temperature may be of some advantage in protecting tender plants, but less favourable impacts will be seen on species needing frost to germinate or set seed (such as daffodils and apples). Greater choice of tender plants must be offset against the dilution of historic design interest and accuracy. Warmer temperatures will require changes to staff and visitor arrangements; they may also increase opportunities for revenue-raising outdoor events.

Plant physiology and distribution

The potential changes in plant physiology and distribution are already well recognised in this sector, with the emphasis being on active management: ‘there are too many variables to plan ahead.’

Pests and diseases

Warmer conditions were recognised as greatly increasing the risks from pests and diseases: particularly for plant collections and structural planting. Historical integrity may prove difficult to maintain for this reason alone. Recent attempts at designing less-intrusive care regimes may have to be reconsidered: ‘The National Trust is attempting to move away from use of chemicals, but this situation may force an increase.’

Rainfall

Soil moisture content

Future difficulties in maintaining soil moisture contents were felt to require improvements in soil and land husbandry practices.

Water table height and chemistry

Water table height and chemistry changes may also provoke ‘problems with maintaining levels of ornamental lakes, and with the bore holes and water supplies from wells and springs on which gardens and water features depend.’ Corres pon -dents noted that regular soil analysis and testing will become vital, especially for historic plant collections.

Fluvial flooding

A likely outcome of heavy rain is a significant increase in fluvial flooding. This is not only directly damaging, but also of concern for erosion. Correspondents noted that runoff flooding has been exacerbated by changes in land cover such as the building of roads and hard stands for car parking replacing front gardens.

Coastal flooding

Coastal properties may also be at risk from flooding associated with sea level rise and storm surges. For these sites, the after effects of floods are exacerbated by the salinity of the flood water; all these problems are currently seen in the National Trust gardens at Westbury Court, and a number of other sites around the country such as Fountains Abbey and Alfriston. ‘Wider catchment management is needed to minimise impact. The cost of flood protection/drainage channel diversions onto surrounding land is likely to be very high. We need to plan ahead financially for these situations, which we have not done so far.’ As for buildings and archaeology, coastal loss was generally considered to be unavoidable: ‘It is against National Trust policy to protect land from coastal erosion.’

Other factors

issue for parks and gardens: ‘Other landscape features, such as heath and scrub or unmanaged sites, are much more likely to be a fire risk.’

In summary, correspondents noted that the opportunities for a more diverse choice of plants must be offset against losses of historical integrity, and likely increases in maintenance costs. ‘English Heritage is unlikely to support reconstruction of a historic park and garden.’

䡵General Issues raised by the Questionnaire Respondents

From the responses and the additional comments offered, it is clear that certain issues emerged as of prime importance.

Recognition and status of the historic environment:

• The historic environment has an ambiguous status within central, regional and local government and various other agencies.

• It is peripheral to the activities of both cultural and environmental sectors, instead of being properly integrated into both.

• A more integrated approach to the management of the historic environment is needed if the necessary measures to moderate the effects of climate change are to materialise. • Governments do not take the longer-term view, and although climate change is crucial

and critical, it is not a high priority.

Conflict between planning guidance and ‘preservation in situ’ of archaeological remains:

• Climate change could have serious implications for the current practice of archaeology and the planning process.

Factors affecting the official response to the effects of longer-term change: • Lack of understanding of longer-term change means that existing resources for

management are expected to go further.

• There are insufficient incentives for land owners to manage the historic environment in a beneficial way, compared to land stewardship.

• Most pro-active conservation measures are more easily directed towards areas that are under least threat. It is, for example, easier to implement conservation schemes on dry earthwork sites of minimal quality, than to secure the beneficial management of vastly more valuable buried wet (or semi-wet) sites, which are also under much greater threat. • Fenland archaeology poses particular problems: most survives in areas under cultivation

which do not fall within areas of wider environmental protective designations.

• Specific development proposals attract disproportionate resources to archaeological sites even when the quality of the site is not high.

• Coastal sites are under the very highest level of threat: there is no management strategy at present, and it is unrealistic to expect that development funding will be available for investigation and recording. Developers, unsurprisingly, are not willing to purchase land that is about to be eroded away by the sea. Without a developer to take responsibility for the demise of an archaeological site, there is no one to call upon presently to pay for recording prior to destruction.

Research and monitoring

• There is a lack of good data on the effects of natural and artificial environmental change. More fundamental data is needed regarding the effects of climate change, as well as synthesising existing data from the natural heritage.

• There has been no monitoring of representative samples of archaeological sites for a long enough period, since the ‘preservation in situ’ strategy is relatively recent.

• The understanding of the behaviour of the materials is poor; with climate goal posts being shifted, this will worsen.

• Resources need to be devoted to understanding how materials will respond to change in marine, coastal and terrestrial environments (and both above and below ground).

Management and funding issues:

• Changes are needed to prioritise and coordinate available funding.

• Grant-giving bodies need to make crucial adjustments to their approach to encourage an increase in regular, well-considered maintenance.

• There is a need for appropriate and feasible management/conservation plans for historic sites, and for these to address nationally standardised issues.

• Local government is effectively powerless in implementing positive change, preventative measures, or even rescue measures without extra funding. Furthermore, most of the issues appear to be the remit of central rather than local government.

• In terms of physical losses to archaeology (as distinct from buildings) in the East of England, arable agriculture has always been, and seems likely to continue to be, the major cause.

• Virtually no control over losses to agricultural destruction exist even in the case of Scheduled Ancient Monuments.

4.2

Site visits

From the outset it was clear that climate change will present unique local management and maintenance challenges. It was therefore important to obtain the views of staff actively engaged in the protection of historic houses and contents, archaeological sites and ruins, and parks and gardens. To get a clear sense of how climate change might impact on local stewardship decisions, a number of short site visits took place, with the aim of meeting those responsible to discuss problems in situ.

Sites in the East of England and the North West were chosen in consultation with English Heritage experts to cover as wide a range of issues as possible likely to arise from the impact of climate change on the historic environment. While most of these sites were the responsibility of English Heritage, sites cared for by other organisations were also visited. These were Sutton Hoo (National Trust), Flag Fen Bronze Age Site (Fenland Archaeological Trust), and Birkenhead Park on the Wirral (Metropolitan Borough of Wirral). A list of sites and site characteristics may be found in Annex 2.

Dilemmas facing those responsible for the historic environment:

• The biggest decision will probably be over which sites to ‘let go’. There will never be the money to save everything. Decisions on the value and significance of a site may need to be made upfront before money is spent on short-term or no-real-hope projects.

• We should be planning for climate change and not trying to hold the cultural heritage in stasis, and this should be communicated to the public.

• If climate change means that deposits begin to deteriorate if not excavated (and thus preserved by recording), the current strategy of preserving in situ may lead to the destruction rather than the preservation of the archaeological heritage. If this is the case, then preservation by record should be favoured wherever possible.

Issues raised during site visits

The important issues arising from the site visits are summarised below.

䡵Climate change effects are already being felt on all types of site

Almost all managers had already noted progressive changes in the climate patterns of sites, and associated increases in deterioration. Some of these were:

● increased erosion, especially associated with increased storminess (Sutton Hoo)

● problems with local flooding (Audley End)

● problems with sustaining turf (Birkenhead Park, Furness Abbey)

● changing patterns of pests and diseases (such as the year-round presence of Canada geese at Birkenhead Park)

● problems with rainwater disposal (Audley End, Beeston Castle).

䡵Coastal loss

A visit to Dunwich in the East of England, where most of a large medieval town has been lost to the sea, illustrated that while loss has always been a critical issue for coastal sites, the situation is being made worse by climate change. It may be possible in certain circumstances to save some sites. However, the choice must include an assessment of the value and significance of not only the sites being targeted for protection, but also of neighbouring sites since localised defences disrupt natural coastal processes. Endangered sites of less than first importance – such as Languard Fort, near Folkestone – may have to be recorded and abandoned, despite the care and cost already spent on their conservation.

䡵Competition with surrounding land use

This issue, already of crucial importance for many sites, is likely to be exacerbated by climate change. For example, Sutton Hoo is neighboured by turf farms that increase the risk of erosion. Summer water shortages, too, are likely to see sites competing with farming for limited resources (this would impact not only on parks and gardens, but critically on wetlands archaeology such as Flag Fen).

䡵Presentation of ruins

ruins, such as those of Furness Abbey in Cumbria, at risk of wind throw, or increased erosion. Novel methods of protection should be considered: for example, using planting as shelter belts. This of course has implications for the buried archaeology of the site, raising again the issue: what aspects of heritage are we prepared to sacrifice in order to save the rest?

A side issue is the popular use of turf as a ‘green carpet’ around monuments. This cover acts also as a dust control measure, but if it is to be retained as a feature it will be necessary to find more robust grass species. Already lawns are becoming difficult and expensive to maintain, and many may prove to be unsustainable in the long term.

䡵Maintenance

Meticulous maintenance and monitoring of condition, always central to successful preservation will become more critical as climate changes take effect. For example, drainage and rainwater disposal systems may prove unable to cope with extreme rainfalls: problems will have to be recognised and dealt with immediately, if they are not to become chronic. Historic buildings such as Audley End combine large expanses of roof with complex, often concealed rainwater goods. To date the approach has been to only make concealable changes to down pipes and guttering, but site managers and advisers felt that this approach might not be enough in the future.

䡵Funding issues

There is insufficient funding for maintenance, despite its critical importance for preservation. Grants are given for capital works, but not for day-to-day management, and budgeting well in advance – crucial for forward planning – is almost impossible. For example, Birkenhead Park has been granted £11.4 million by the Heritage Lottery Fund and others to restore the park and install a visitor centre, yet it is difficult to find a source of funding that secures maintenance beyond the next ten years. It is clearly unsustainable to invest large sums in restoration schemes without including provision for long-term upkeep, especially in the light of a changing climate.

It is arguable, indeed, that the current funding structures may reward poor maintenance.

䡵Lack of local input into planning

managers and maintenance staff. Decision-making needs to utilise staff with local knowledge of planning issues. Although consistent policies are crucial, they should not be implemented in a way that prevents routine maintenance or emergency decisions being made by local management.

䡵Internal links

The English Heritage intranet was considered to be an under utilised resource. Its potential role as a central clearing-house for information and as a link between managers of remote sites and the centre and to each other was emphasised. Another example of how internal links might be improved is given in the case study of Beeston Castle.

Beeston Castle is an isolated site, and the most regular work there is undertaken by the gardeners, who trim turf and remove aggressive wall plants. The gaps in the mortar made by the removal of these plants remain however until

maintenance staff can be called in to fill them with approved mortar. Here there would be not only a clear cost saving, but also a significant improvement in care, if the gardeners could be given pre-prepared mortar and taught to make the appropriate small repairs themselves.

Case Study: