_____________________________________________________________________________________________________

*Corresponding author: E-mail: bakhiwu@yahoo.com;

(Past name: British Journal of Medicine and Medical Research, Past ISSN: 2231-0614, NLM ID: 101570965)

Giant Extracranial Carotid Artery Pseudo-aneurysm

Causing Acute Airway Obstruction

B. I. Akhiwu

1*, S. D. Peter

2, J. M. Njem

3, E. O. Ojo

2, I. O. Omofuma

2,

A. G. Adewale

2and

A. S. Adoga

41Department of Dental and Maxillofacial Surgery, University of Jos/Jos University Teaching Hospital,

Nigeria.

2Department of Surgery, General Surgery Unit, Jos University Teaching Hospital / University of Jos.

Nigeria. 3

Department of Surgery, Cardiothoracic Unit, Jos University Teaching Hospital/ University of Jos, Nigeria.

4Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Jos University Teaching Hospital/ University of Jos, Nigeria.

Authors’ contributions

This work was carried out in collaboration between all authors. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Article Information

DOI: 10.9734/JAMMR/2018/43733

Editor(s):

(1) Dr. Chan-Min Liu, School of Life Science, Xuzhou Normal University, Xuzhou City, China.

Reviewers:

(1) Priv.-Doz. Slaven Pikija, Paracelsus Medical University, Austria. (2)Manas Bajpai, NIMS Dental College, India. (3)G. H. Sperber, University of Alberta, Canada. (4)Pasqualino Sirignano, “Paride Stefanini” “Sapienza” University of Rome Policlinico Umberto I, Italy. (5)Troupis Theodore, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Greece. Complete Peer review History:http://www.sciencedomain.org/review-history/27318

Received 11 July 2018 Accepted 21 September 2018 Published 20 November 2018

ABSTRACT

Aneurysms of the carotid artery are known to be very rare. When they occur, they can result in upper airway obstruction, vascular embolisation of blood clots, stroke, or other neurologic deficits. Most importantly if they do rupture, it may be fatal. The present study reports a 24-year old male with a carotid artery aneurysm initially misdiagnosed as tuberculous adenitis that later developed dyspnoea, dysphagia and hoarseness. He was managed using a multidisciplinary approach. Intra-operative findings showed a huge pseudo-aneurysmal sac, 14 cm ×12 cm, completely occluding the airway and filled with blood and clots. The sac was communicating with the mid medial aspect

of the common carotid artery via a 0.7 cm longitudinal tear. He had surgery and excision of the aneurysmal sac measuring 12 cm × 14 cm and recovered with neuropraxia of the right hypoglossal nerve which subsequently resolved.

Keywords: False aneurysm; common carotid artery; giant; surgical excision.

1. INTRODUCTION

Extra-cranial carotid artery aneurysms (ECCA) are uncommon, and occurrence of isolated aneurysms of the extra-cranial carotid artery is even rarer. Overall, extracranial carotid artery aneurysm accounts for less than 1% of all arterial aneurysms [1-3]. These aneurysms can be true aneurysms involving all layers of the carotid arterial wall or false aneurysms which represent a collection of blood, held around the vessel by a wall of connective tissue which does not involve the vessel wall [1-3].Most studies have reported the average aneurysmal size of between 3.5-5 cm [2,3], and most of the pseudo-aneurysms are post-traumatic or anastomotic in origin [1-3]. The mortality rate in non-operated patients with carotid artery aneurysm has been reported to be up to 70% [1] while in the operated cases the mortality rate falls to 28% [3].

It has been reported that open surgical repair remains the most appropriate approach for ECCA [3-5].

2. CASE REPORT

A.S was a 24-year old man, who was presented initially to the medical outpatient department (MOPD) with complaints of a 4 months old right- sided neck swelling. The swelling was initially peanut sized and located at the right upper lateral neck region, but progressively increased in size until it became the size of his clenched fist. It did not regress at any time, and no swellings were noticed elsewhere in the body. It was initially painless but later became tense and painful, the pain was throbbing, and severe enough to disrupt his daily activities. There was also associated right sided throbbing headache, which was only slightly relieved by analgesics.

There was no preceding history of trauma, chronic cough or contact with another individual with a cough suggestive of tuberculosis. Neither was any history of fever, night sweats or voice changes prior to swelling and the review of systems were not contributory.

At the presentation to the MOPD, the significant clinical findings were significant cervical lymph node enlargement. The initial diagnosis was a possibility of Tuberculous adenitis. A Mantoux test done was of 14mm, and Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate was 90mm/hr, Full Blood Count was essentially normal. Based on these, he was placed on anti-tuberculous drugs. However, when the swelling continued to increase in size despite treatment, he was referred to the Surgical out Patient Department (SOPD) for a lymph node biopsy and histology.

In the SOPD, Neck examination revealed an oval shaped pulsatile swelling measuring 10cm × 8cm at the right lateral aspect of the neck, extending from just below the right jaw to the mid- neck, the mass was non- tender, with no differential warmth. It was not attached to the skin, but fixed to the underlying structures (see Fig. 1). On examination of the respiratory system, the chest was symmetrical, with the trachea deviated to the left. Other systemic examinations were normal. Common carotid aneurysm, aneurysmal bone cyst were considered as differentials.

Investigations to verify this diagnosis included a Doppler ultrasound scan and a head and neck CT scan with contrast. Doppler US showed dilated right common carotid around its bifurcation (4.4cm in diameter) with turbulent blood flow.

CT scan with IV contrast (see Fig. 2) showed a well- circumscribed hypodense right sided neck mass, extending from below the mandible to the mid- neck region, displacing and compressing the airway. There was extravasation of contrast into the mid portion of the swelling. The result of other tests Liver Function Tests, clotting profile, hepatitis screen were normal.

The patient was admitted for neck exploration. A

multidisciplinary team involving the

patient had emergency tracheotomy with neck exploration via an elliptical skin incision.

Intra-operative findings were those of a huge pseudo-aneurysmal sac, 14 cm × 12 cm completely occluding the airway, with attenuated strap muscles. The sac was filled with blood and clots. The sac was communicating with the mid medial aspect of the common carotid artery via a 0.7 cm ×1.5 cm longitudinal deficit. Proximal and distal control of the jugular vein was achieved. The hematoma cavity was entered and the clots were evacuated, the outer aspect of the sac was excised, a medial arteriography was affected longitudinally with continuous 4.0 polypropylene sutures, which was watertight. Intra-operative blood loss was estimated to be 1.5 Liters, and he was transfused with 4 units of whole blood intra-operatively.

The patient was admitted into the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) postoperatively during which he had reactionary haemorrhage secondary to over heparinisation which was promptly managed with pressure packing and reversal of anticoagulation using 50mg of intravenous protamine sulphate. He was subsequently placed on intramuscular Enoxaparin 40 mg for thrice daily. He was transferred to the ward after 48 hours. The improvised tracheostomy tube was weaned off on the 4th post-operative day.

There was a break down of the surgical wound seven days postoperatively which was managed with daily wound dressing. He was discharged on the 26th day postoperative after the closure of the wound. Repeat Doppler of the neck before

discharge showed normal flow and calibre along the right carotid artery. On discharge, he was noticed to have palsy of the right hypoglossal nerve which was possibly due to neuropraxia injury during dissection. He was seen 6 weeks postoperatively (see Fig. 5) and the palsy of the right hypoglossal nerve had resolved, and the incision site had also healed with a hypertrophied scar.

Informed consent was obtained from the patient and the Institutional review board of the teaching hospital.

3. DISCUSSION

Aneurysms of the common carotid artery are rare and on the average do not usually exceed a size of about 5cm [1-3].The largest reported carotid artery aneurysm was by Danato et al. in 2006 where an aneurysm measured 8.5 cm [6]. However, in this report, the carotid aneurysm observed measured 14 cm × 12 cm.

The typical signs of carotid aneurysms include the presence of a pulsatile latero-cervical mass [6],which was observed in this patient. As the diameter of the aneurysm increases, it usually compresses on the adjacent structures, causing localised symptoms, pain, deviation of the trachea and oesophagus and neurological involvement [2,6]. This was the case in this patient with the deviation of the trachea on examination, and he subsequently developed dysphagia, difficulty in breathing and hoarseness.

Fig. 2. CT scan with IV contrast showing a well- circumscribed hypodense right sided neck mass, extending from below the mandible to mid- neck region, displacing and compressing

the airway

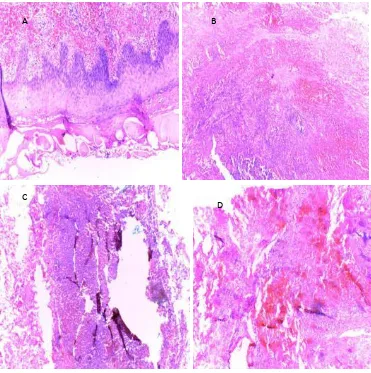

Fig. 4. The histological slide of the excised aneurysm

A Shows an acanthotic epidermis with prominent scale crust. The underlying dermis shows extensive haemorrhage from ruptured vessels deep within the stroma.

B Image shows fibrocollaginous stroma containing area of haemorrhage and necrosis.

C Shows 2 channels created within the underlying stroma. Left channel is a pseudoaneurysmal channel filled with blood.

D Section shows multiple microvenular out pouching into the stroma with associated foci of rupture and haemorrhage.

The major causes of a carotid aneurysm are degeneration and atherosclerosis. It could also be post-traumatic, post-endarterectomy, due to arterial dysplasia or may be related to infections, irradiation or cervical surgery. Currently, atherosclerotic etiologies account for 40% to 70% of cases [7,8]. Other differentials for carotid artery aneurysms include Takayasu Arteritis, aneurysmal bone cyst and Marfans syndrome. Takayasu arteritis is however unlikely in this patient because this is a disease that occurs commonly in women of childbearing age and it manifests as a granulomatous inflammation of the aorta and its branches [9]. These findings

were not supported by this patient’s gender and histology. Marfans syndrome [10] is another known cause of aneurysms, but this is unlikely in this patient because the commonly clinical habitus and presentations (skeletal, cardiac and eye) seen in Marfan’s syndrome are not present in this patient. Aneurysmal bone cyst (ABC) [11] is also another differential to be considered in patients that present like this. ABCs tend to grow rapidly and destroy cortical plates resulting in bony expansion and facial asymmetry. It is a benign tumour-like lesion that is described as "an expanding osteolytic lesion consisting of blood-filled spaces of variable size separated by

A B

C

connective tissue septa containing trabeculae or osteoid tissue and osteoclast giant cells” [12].

Fig. 5. 6 weeks post op with complete wound healing and a hypertrophied scar

In this patient, however, the aetiology of the aneurysm was unknown.

The patient had an exploration of the neck with excision of an aneurysmal sac. According to several authors [3-5,13], open repair remains the method of choice in treating carotid artery aneurysms. With surgical intervention helping to significantly reduce the possible mortality [1].

For this kind of surgery torrential bleedin anticipated. Therefore preparations were made to tackle this. A long incision was made along the anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle to allow for a good exposure of the great vessels, and a maxillofacial surgeon was in attendance in case mandibulotomy became necessary. Both the carotid and the jugular vessels in the carotid sheath easily dissected out proximally. After which gauze was placed snugly over each vessel with vascular clamps over the gauze so that the clamps do not come in dir contact with the vessels at the proximal portion. The distal portion was difficult to assess initially because an aneurysm abutted on the medial surface of the angle of the mandible but during the dissection, the aneurysm inadvertently ruptured and decompressed making it possible to assess the distal portion while digital pressure was maintained by the assistant. Subsequently, connective tissue septa containing trabeculae or

cells” [12].

Fig. 5. 6 weeks post op with complete wound healing and a hypertrophied scar

In this patient, however, the aetiology of the

The patient had an exploration of the neck with sac. According to pen repair remains the method of choice in treating carotid artery aneurysms. With surgical intervention helping to significantly reduce the possible mortality [1].

For this kind of surgery torrential bleeding was anticipated. Therefore preparations were made to tackle this. A long incision was made along the anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle to allow for a good exposure of the great vessels, and a maxillofacial surgeon was in e mandibulotomy became necessary. Both the carotid and the jugular vessels in the carotid sheath easily dissected out proximally. After which gauze was placed snugly over each vessel with vascular clamps over the gauze so that the clamps do not come in direct contact with the vessels at the proximal portion. The distal portion was difficult to assess initially because an aneurysm abutted on the medial surface of the angle of the mandible but during the dissection, the aneurysm inadvertently ompressed making it possible to assess the distal portion while digital pressure was maintained by the assistant. Subsequently,

the aneurysmoplasty was carried out in such a way that the common carotid artery was in direct communication with the internal carotid vessel.

It is, however, important to note that where available, Endovascular treatment using stents is also a viable option [14,15]. Unfortunately in this case, endovascular treatment which is technique sensitive and requires facilities was not av There have been reports of preoperative, and postoperative complications of surgically treated carotid artery aneurysm and these have been known to include hematoma, transient neurological deficits and fatal stroke [9]. This patient was noticed to develop palsy of the right hypoglossal nerve which subsequently resolved. The palsy was probably due to the neuropraxic injury.

4. CONCLUSION

In conclusion, the study has described the presence of a very large carotid artery pseudoaneurysm, problems encountered and how they were managed.

CONSENT

Informed consent was obtained from the patient and the Institutional review board of the teaching hospital.

ETHICAL APPROVAL

As per international standard or university standard ethical permission has been collected and preserved by the authors.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Research reported in this publication was supported by the Fogarty International Centre (FIC) of the National Institutes of Health and also the Office of the Director, National Institutes ofHealth (OD), National Institute of Nursing Research (NINR) and the National Institutes of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) under award number D43TW010130. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the

views of the National Institutes of Health”

COMPETING INTERESTS

Authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

the aneurysmoplasty was carried out in such a way that the common carotid artery was in direct

carotid vessel.

It is, however, important to note that where available, Endovascular treatment using stents is also a viable option [14,15]. Unfortunately in this case, endovascular treatment which is technique sensitive and requires facilities was not available. There have been reports of preoperative, and postoperative complications of surgically treated carotid artery aneurysm and these have been known to include hematoma, transient neurological deficits and fatal stroke [9]. This develop palsy of the right hypoglossal nerve which subsequently resolved. The palsy was probably due to the neuropraxic

In conclusion, the study has described the presence of a very large carotid artery encountered and

Informed consent was obtained from the patient and the Institutional review board of the teaching

As per international standard or university been collected

Research reported in this publication was supported by the Fogarty International Centre (FIC) of the National Institutes of Health and also the Office of the Director, National Institutes alth (OD), National Institute of Nursing Research (NINR) and the National Institutes of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) under award number D43TW010130. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health”

REFERENCES

1. Pourier VEC, van Laarhoven CJH,

Vergouwen MDI, Rinkel GJE, de Borst GJ. Prevalence of extracranial carotid artery aneurysms in patients with an intracranial aneurysm. PLoS One. 2017; 12(11):e0187479.

2. Argenta R, Braun SK. Surgical repair of an extra-cranial carotid aneurysm. J Vasc Bras. 2015;14(1):84-87.

3. Garg K, Rockman CB, Lee V, Maldonado TS, Jacobowitz GR, Adelman MA, et al. Presentation and management of carotid artery aneurysms and pseudoaneurysms. J Vasc Surg. 2012;55(6):1618-22.

4. Longo GM, Kibbe MR. Aneurysms of the carotid artery. Semin Vasc Surg. 2005;18: 178-8.

5. El-Sabrout R, Cooley DA. Extracranial carotid artery aneurysms: Texas heart institute experience. J Vasc Surg. 2000; 31(4):702-12.

6. Donato GD, Giubbolini M, Chisci E, Setacci F, Setacci C. Giant external carotid aneurysm: A rare cause of dyspnoea, Dysphagia and Horner’s syndrome. EJVES Extra. 2006;11:19–22.

DOI: 10.1016/j.ejvsextra.2005.10.003 Available:http://www.sciencedirect.com 7. De Luccia N, da Silva ES, Aponchik M,

Appolonio F, Benvenuti LA. Congenital external carotid artery aneurysm. Ann Vasc Surg. 2010;24(3):418.e7-10. 8. Gralla J, Remonda L, Schmidll J, Kohll S,

Do DD, Schroth G. Mycotic aneurysm of

the external carotid artery as a complication of bacterial endocarditis: Endovascular exclusion with an uncovered stent. EJVES Extra. 2004;8(2):37-8. 9. Jennette JC, Falk RJ, Andrassy K, Bacon

PA, Churg J, Gross WL. Nomenclature of systemic vasculitides. Proposal of an international consensus conference. Arthritis Rheum. 1994;37(2):187-92.

10. Keane MG, Pyeritz RE. Medical

management of marfan syndrome.

Circulation. 2008;117(21):2802–13. 11. Bajpai M, Pardhe N, Vijay P. Aneurysmal

bone cyst of mandible with classical histopathological presentation. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2018;28(2):174. 12. Schajowicz F. Aneurysmal bone cyst.

Histologic typing of bone tumours. Berlin: Springer-Verlag. 1992;37.

13. De Borst GJ, Pourier VEC. Treatment of aneurysms of the extracranial carotid artery: Current evidence and future perspectives. J Neurol Neuromed. 2016; 1(6):11-14.

14. Yamamoto S, Akioka N, Kashiwazaki D, Koh M, Kuwayama N, Kuroda S. Surgical

and endovascular treatments for

extracranial carotid artery aneurysm: report of six cases. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2017;26:1481-1486.

15. Welleweerd JC, den Ruijter HM, Nelissen BGL, Bots ML, Kappelle LJ, Rinkel GJE. Management of extracranial carotid artery aneurysm. European Journal of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery. 2015;50:141-147.

_________________________________________________________________________________ © 2018 Akhiwu et al.; This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License

(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly cited.

Peer-review history: