ABSTRACT: Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is characterized by abdominal pain or discomfort, bloating, and constipation or diarrhea; the pain is typically relieved by defecation. The diagnosis is not one of exclusion; it can be made based on the answers to a few key questions and the absence of “alarm” symptoms. Judicious use of fiber supplements, the elimination of particular foods, and regu-lation of bowel function can help relieve symptoms. Polyethylene glycol or lubi-prostone can be used to treat IBS with constipation. Loperamide (and if symp-toms are severe, alosetron) are of bene-fit in IBS with diarrhea (although alose-tron carries a small risk of ischemic colitis and severe constipation). Antidepres-sants (both tricyclics and selective sero-tonin reuptake inhibitors) may be used to treat IBS. Probiotic therapy or rifaximin may help reduce IBS symptoms including bloating.

Key words: irritable bowel syndrome, diarrhea, constipation, abdominal pain, fiber therapy, alosetron, rifaximin, probiotics

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) was once considered a psychosomatic condition,1 but early views appear to be incorrect. IBS is clearly not just part of a somatization syndrome, and the symptoms are not imagined. Ac-cumulating evidence indicates that there is an organic gut component to IBS, and that the disease can sub-stantially impair the health and well-being of affected patients.1,2

Recent research, in addition to shedding new light on the patho-physiology of IBS, has also suggest-ed new treatments. In this article, I present the latest thinking about this common problem, and I will discuss the pros and cons of the many thera-peutic options now available.

SYMPTOMS AND SIGNS

The principal symptoms of IBS are abdominal discomfort or pain, bloating, and constipation or diar-rhea (which can be represented by the simple mnemonic “ABCD” [Table 1]).1 Stool consistency in the disease varies, and individual cases of IBS are typically classed as 1 of the following 4 types:

•IBS with constipation, in which stools are usually firm and hard (as a result of slow intestinal transit). •IBS with diarrhea, in which stools are usually loose or water y (as a result of rapid intestinal transit).2 •Mixed IBS pattern, in which pa-tients have both types of stool form (sometimes within as short a period as a single day).

•IBS with alternating stool pattern, in which patients have a prolonged period of constipation or diarrhea before a different stool consistency predominates.

The feelings of bloatedness that are common in patients with IBS are sometimes associated with visible abdominal distention. Increased ab-dominal girth has been objectively identified using plethysmography.3 A few may even appear temporarily

Irritable Bowel Syndrome:

Rational Therapy

Dr Talley is pro-vice chancellor and professor, University of New-castle, Australia, and adjunct profes-sor of medicine at Mayo Clinic, and University of North Carolina.Dr Talley is a consultant for AccreditEd, ARYx, Astellas Pharma Inc. US, Astra Zeneca, Care Capitol, Edusa Pharma, Eisai, Inc., Elsevier, Focus Medical, In2MedEd, Johnson & Johnson, Meritage Pharma, NicOx, Novartis, Ocera, Salix, Sanofi-Aventis, Spire Learning, Theravance, and XenoPort. He has received financial support from GlaxoSmithKline, Dynogen, and Tioga.

Irritable Bowel Syndrome: Rational Therapy

pregnant. Distention typically occurs later in the day or after meals.

In addition, patients may com-plain of other GI symptoms, especial-ly heartburn and nausea. However, these do not usually dominate the clinical presentation unless another problem is present.1 Extra-bowel symptoms also occur (see Table 1).

CAUSES

Although IBS is still not fully understood, some facts about its ori-gins and pathophysiology have been established.1,2 In addition, there are a number of intriguing theories for which some supporting evidence is available.

Genetic basis. IBS probably has a genetic component.4 The dis-ease runs in families, and this famil-ial clustering is not fully explained by the learning of abnormal behav-ior from parents or others. However, the exact genes involved remain to be identified. There is some evi-dence to suggest that the culprit genes may be ones that affect multi-ple systems, such as those that regu-late the inflammatory process or se-rotonin reuptake; this might explain both the intestinal and extraintesti-nal manifestations of the disease.

Infectious origins. IBS can occur after infection.5,6 In about 10% of patients, a clear-cut bacterial, viral, or parasitic-induced gastroenteritis seems to have precipitated their chronic symptoms.

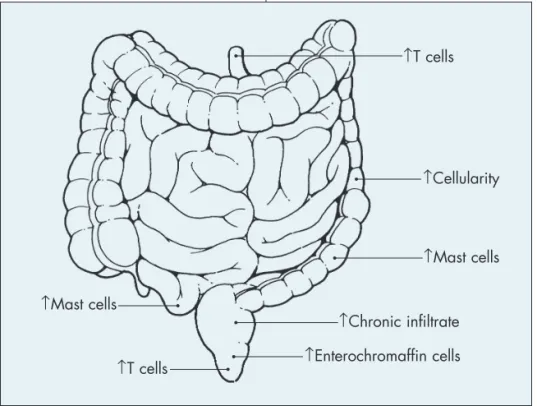

Role of inflammation. Activa-tion of the immune system is seen in a subset of patients with IBS, which suggests an ongoing low-grade in-flammatory disease process.7 Subtle inflammatory changes—increases in the number of mast cells in the colon and small bowel, and in the number of lymphocytes8 (Figure)—are seen in at least some patients with IBS.1,8 The mast cells seem to localize close to nerves; this phenomenon has been correlated with the abdominal pain associated with IBS.9 Inflammation can affect GI motor and sensory func-tion, both of which are known to be

disturbed in IBS. Thus, disturbed gut motility, which accounts at least in part for the symptoms of constipation and diarrhea in the syndrome,10 may be secondary to subtle inflammation.

Gut hypersensitivity to balloon distention. This has been suggested as a biologic marker for IBS. Howev-er, gut hypersensitivity to distention is relatively difficult to test in clinical practice.10 It is also uncertain wheth-er gut hypwheth-ersensitivity is a direct cause of symptoms. Inflammation might induce gut hypersensitivity.

Small-bowel bacterial over-growth. Recent research has focused on the possibility that small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) may be a factor in IBS.11 It is hypothesized that slowed intestinal transit predis-poses to increased numbers of nor-mal bacteria, with the possibility that abnormal flora may then colonize the gut as well. Bacterial fermenta-tion of food products may release gas that can cause distention of the bowel, with bloating and discomfort or pain in those with a hypersensi-tive gut.

Table 1 – The ABCs of irritable bowel syndrome

A bdominal pain or discomfort—typically in the lower abdomen but could be anywhere

Bloating or visible distention

Constipation: hard, difficult-to-evacuate, or infrequent stools

Diarrhea: loose, watery, or frequent stools

E xtra-bowel symptoms such as fatigue, headache, backache, muscle pain, urinary frequency, and sleep disturbance

Figure – Biopsy studies in patients with irritable bowel syndrome have revealed a number of markers of a low-grade inflammatory process.

↑Mast cells

↑T cells ↑Enterochromaffin cells

↑Chronic infiltrate

↑T cells

↑Cellularity

testing are more likely to be abnor-mal in patients with IBS, but this may just be the result of fast intesti-nal transit. Trials of antibiotic thera-py for IBS have shown positive re-sults, with up to one third of patients responding; however, no data from long-term trials are available.12,13

Neurologic component. The brain plays a central role in the per-ception of pain.1 The brain can heighten or diminish the sensation of pain originating in the gut or any-where else. Positron emission to-mography and MRI show that key pain signaling areas in the brain are activated more often in patients with IBS than they are in controls.14

In addition, psychological factors may amplify pain sensations. This may explain why patients with IBS are more likely than others to be anxious or depressed.1 However, anxiety or depression in patients with IBS might be secondary to living with a chronic disease. Alternatively, intriguing data suggest that inflammation may itself induce anxiety or depression.15 Final-ly, it is possible that any genetic pre-disposition to IBS may also genetically predispose to the development of anx-iety or depression.4 Not every patient with IBS is clinically anxious or de-pressed; thus, the relationship be-tween IBS and psychological distur-bances is likely complex.

DIAGNOSIS

The diagnosis of IBS can be sim-ply and safely made by taking a short history. IBS is not a diagnosis of ex-clusion.1,16 The answers to the follow-ing questions determine whether the patient meets the Rome III criteria2: •Is your pain or discomfort often re-lieved by defecation?

If the patient answers yes to 2 of the 3 questions listed above, the pro-visional diagnosis is IBS until proved otherwise.

In addition to evaluating for the Rome III criteria, always ask about “alarm” symptoms or signs (Table 2)

that can signal the presence of an im-portant structural disease.2 If any of these are present, prompt investiga-tion to exclude serious disease is warranted. If none are present, confi-dence in the diagnosis of IBS is in-creased and further workup is sel-dom needed.16

In the past, it was recommend-ed that patients with suspectrecommend-ed IBS be screened for a number of condi-tions, including thyroid disease, ane-mia, and structural disease of the colon. However, evidence indicates that a diagnostic test panel is no more likely to show significant ab-normalities in a patient with typical

In the patient who is 50 years of age or older and has not had a screening colonoscopy, it is reason-able to evaluate the structure of the colon with a colonoscopy to exclude colon cancer. However, in younger patients in whom no alarm features

are present, a structural evaluation of the colon is usually unrevealing.16 If the patient has diarrhea and is scheduled for colonoscopy, micro-scopic colitis should be ruled out by taking random biopsies, as this dis-ease can mimic IBS.17

If findings in the histor y or physical examination suggest anoth-er disease, appropriate testing is war-ranted. For example, celiac disease may present with IBS-like features (even constipation). Although such a presentation of celiac disease is un-common, measurement of tissue transglutaminase antibody should be routine if you suspect this possibility

Table 2 – “Alarm” symptoms and signs that require

prompt investigation

•First onset in an older patient (≥ 50 years)

•Weight loss

•Progressive dysphagia

•Evidence of bleeding or dehydration

•Evidence of steatorrhea

•Recurrent vomiting

•Fever

•Elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate or C-reactive protein level

•Anemia or leukocytosis

•Blood or pus in stool

•Hypokalemia or persistent diarrhea during fasting

• Strong family history of colon cancer, inflammatory bowel disease, or celiac disease

(eg, in all those with diarrhea or mixed IBS–like symptoms).16,18

If a patient responds well to an initial trial of treatment for IBS, fur-ther testing is not needed. On the other hand, if alarm symptoms or signs are present or develop or if the patient fails to respond to standard therapies, fur ther evaluation and consideration of referral to a gastro-enterologist are indicated.

TREATMENT

Providing patients with a positive diagnosis and an explanation for their symptoms is important to the success of any treatment. Although IBS is still not fully understood, you can discuss with patients the information in the section on causes. I always empha-size to patients that, in my view, IBS is a real disease of the gut that we are just beginning to understand.

Keep in mind that there is a ro-bust placebo response (about 30%) in patients with IBS.19 Reassurance, ed-ucation, and a positive diagnosis (Table 4) probably help maximize the placebo response.1 Encourage physical activity, which may help symptoms.

Avoid unnecessary surgery. Pa-tients with IBS often are referred to

surgeons and as a result may have surgery (eg, cholecystectomy, hyster-ectomy) that usually does not address the cause of pain in the long term.20

Patients may experience temporary relief after such procedures, but IBS symptoms almost invariably return.

General treatments. A number of conser vative measures can help ameliorate symptoms. These include fiber therapy, other dietary interven-tions, and other measures to regu-late bowel function.

Fiber. Fiber can help regulate bowel function.21 Adding fiber to the diet can be particularly helpful in pa-tients who have IBS with constipa-tion. A daily intake of 20 to 30 g of fiber is considered healthy; however, most Americans consume only about half of this. Supplementation with unprocessed wheat bran is often rec-ommended, but there is no evidence that it actually helps with most IBS symptoms (and it may worsen symp-toms in some cases).16 Commercial fiber supplements containing psylli-Irritable Bowel

Syndrome: Rational Therapy

Table 3 – Prevalence of organic disease in patients who met

symptom-based criteria for irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)

Patients General

Organic GI disease with IBS (%) population (%)

Inflammatory bowel disease 0.51 - 0.98 0.3 - 1.2

Colorectal cancer 0 - 0.51 0 - 6 (varies with age)

Celiac sprue 4.7 0.25 - 0.5

GI infection 0 - 1.5 NA

Thyroid dysfunction 6 5 - 9

Lactose malabsorption 22 - 26 25

From Am J Gastroenterol. 2009.16

Table 4 – Management pearls for irritable bowel syndrome

• Make a positive diagnosis based on symptoms and the absence of “alarm” features.

• Establish the effect of the illness on the patient and on the patient’s psychosocial resources (eg, family supports).

• Determine whether the patient has a comorbid psychiatric disease or an unresolved major loss or trauma.

• Assess the patient’s expectations and hidden fears (eg, find out why he or she has presented now despite long-standing symptoms) and try to address all concerns.

• Provide education, including an understandable explanation of why symptoms might arise, emphasizing that the patient is not alone in his suffering and that the prognosis is benign.

• Avoid giving mixed messages (eg, by reassuring the patient and then ordering extensive tests without an adequate explanation).

• Avoid repeated tests unless there is a new development that suggests structural disease (eg, presentation with new alarm features).

•Base treatment on the principle of patient-based responsibility for care.

•Set realistic treatment goals; consider suggesting a patient support group.

•Organize a continuing care strategy if symptoms are chronic or disabling.

• Consider psychological treatment for patients with moderate to severe symptoms.

so start low and go slow.

Other dietary interventions. Ad-vise patients who have IBS with diar-rhea to avoid artificial sweeteners, which can cause osmotic diarrhea. Avoiding high-fat foods may also prove helpful to some patients, since these can increase gas and cause dys-pepsia, as well as aggravate diarrhea. Some patients with IBS are lac-tose-intolerant and may benefit from limiting their consumption of milk products. A 2-week trial of a lactose-free diet will usually reveal whether lactose has been a contributing factor in a particular patient’s IBS symp-toms and whether he or she will ben-efit from avoiding milk products.21 A hydrogen breath test with a substrate such as lactose can also be used to diagnose lactose intolerance. Keep in mind that most patients who are lac-tose-intolerant can usually drink a glass of milk or the equivalent daily without experiencing any symptoms.

Many patients with IBS report that other specific foods seem to ag-gravate their symptoms. In part, this may reflect their gut hypersensitivi-ty. However, there is evidence that food-elimination diets may help some patients, par ticularly those with diar rhea-predominant IBS. FODMAPs are poorly absorbed sug-ars that are fermented by intestinal bacteria. A randomized trial ob-served that a low FODMAP diet im-proved IBS symptoms.22 Similarly, a gluten-free diet in patients with IBS free of celiac disease was superior to a placebo diet, suggesting gluten in-tolerance may precipitate symptoms in a subset with IBS.23

Regulation of bowel function. Most patients feel better when they are able to move their bowels

regu-ecate, not hurrying to have a bowel movement, and avoiding excessive straining may help some patients with constipation.

Patients who strain excessively, who feel as though there is a block-age in the anal area, or who self-digi-tate may have dyscoordinated evacu-ation. This phenomenon is charac-terized by contraction—rather than relaxation—of the exter nal anal sphincter during straining (a mal-function known as pelvic floor dys-synergia or pelvic outlet obstruc-tion); the result is obstruction of defecation.24 Dyscoordinated evacua-tion can be identified by anorectal manometry testing; in about 75% of patients, it responds to biofeedback training.24

Treatments for IBS with con-stipation. Useful medications used to treat constipation in IBS include polyethylene glycol (PEG), although it is not FDA-approved for IBS. The dose can be titrated to response, and this approach seems safe.16 Another drug approved for constipation-pre-dominant IBS is lubiprostone, a chlo-ride channel activator; it can induce nausea but is otherwise well tolerat-ed, although the efficacy is modest.25

Treatments for IBS with diar-rhea. In patients who have IBS with diarrhea, the best initial treatment for the diarrhea is loperamide.16 Ti-trate the dose until diarrhea is con-trolled (this may require reasonably high doses taken regularly before diarrhea occurs). If loperamide ther-apy fails and the patient clearly has only severe IBS with diarrhea, alos-etron may be tried.16,26 Alosetron, which is FDA-approved specifically for women with severe diarrhea-pre-dominant IBS, is superior to placebo

cian agreement and monitor her regularly. A tricyclic antidepressant, which can slow intestinal transit, is another option for the treatment of diarrhea in IBS.

Off-label use of rifaximin, a non-absorbable antibiotic, for IBS with diarrhea is supported by two large randomised placebo-controlled tri-als.27 Overall, the benefit was modest (10% therapeutic gain above placebo) in the 10 weeks of follow-up after completing the antibiotic.27 Relapse is probably universal, and the bene-fits of re-treatment are unknown.

Treatments for abdominal pain. This is often the symptom of most concern to patients. Pepper-mint oil may provide some relief.16 In patients with coexisting heartburn or dyspepsia, consider a trial of acid suppression therapy. Fiber supple-ments may help abdominal pain, in part by relieving constipation.

To treat the pain of IBS effective-ly, antispasmodic medications (which are anticholinergic) probably need to be given in doses that induce dr y mouth; however, most patients can-not tolerate such high doses. I do try them, but clinical trials have not pro-vided very convincing evidence that these drugs are better than placebo for the treatment of pain in IBS.16

If these simple measures fail, the next step to consider is either an agent specifically for IBS (eg, alose-tron for the patient who has IBS with diarrhea) or a centrally acting agent that may be helpful for pain.

Low-dose tricyclic antidepres-sants can be used to treat pain in IBS. Here they are not prescribed to treat depression, but as a direct treatment for IBS. There is evidence that pa-tients who tolerate these medications

Headline Goes Here To Fill Space: Deck Goes Here to Fill This Space Please Add

and take them as prescribed can ben-efit.28 I generally use an agent, such as desipramine or imipramine, that is least likely to induce anticholinergic side effects. I usually start at the low-est dosage (eg, 10 mg/d, taken at night) and build up slowly, in weekly 10- to 25-mg increments, to a nightly dose of 50 to 75 mg. Drugs in this class may be most useful in patients who have IBS with diarrhea, but in low doses, these agents do not usu-ally worsen constipation significantly. If a patient has a good response, I continue treatment for 6 months and then stop the medication in the hope that a long symptom-free period will ensue before therapy is required again. Data supporting long-term use

of antidepressant therapy in IBS are not available. Warn patients about the potential toxicity of tricyclic anti-depressant therapy.

An alternative approach is to use a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI).16 Because SSRIs speed up intestinal transit, this class of drugs would theoretically be most useful in patients with constipation-predominant IBS, although all sub-groups may benefit.

Treatments for bloating, belch-ing, and flatus. If bloating is a major component of a patient’s abdominal discomfort, consider dietar y treat-ments to reduce gas (see above). A low-fiber diet may be helpful in this setting (because fiber aggravates

gas). In addition, try to reduce any excessive air swallowing by having the patient eat more slowly and avoid chewing gum and smoking.21 Si-methicone and charcoal are proba-bly of little benefit.16

There is some evidence that probiotic therapy may help reduce bloating.29 The strongest evidence is for Bifidobacterium infantis.29 The proposed mechanism of action for probiotics is replacement of existing intestinal flora with the ingested “good” bacteria. Another option is to give a short course of a nonabsorb-able antibiotic such as rifaximin in the setting of IBS with diarrhea.27 However, the long-term benefit of this type of drug is unclear.

For patients in whom belching is a concern, recommend that they try to reduce air swallowing by the means outlined above. Some patients with repeated belching have a ner-vous habit of swallowing air exces-sively (aerophagia). Training in dia-phragmatic breathing can be helpful for such patients.30

If the patient has excessive flatus, consider recommending a diet that avoids flatus-producing foods, such as meat, fowl, fish, and eggs.21 Products that contain chlorophyll or a charcoal cushion can reduce the odor from fla-tus if this is a major problem.21

Other treatment options. Anx-iolytics are probably of only limited benefit in IBS and can be habituat-ing. Thus, long-term use of agents in this class is not recommended in pa-tients with IBS.16 Never prescribe narcotics for IBS pain; these drugs can paradoxically worsen symptoms and lead to narcotic dependence or the narcotic bowel syndrome.31

The benefits of anti-inflammato-ry drugs (eg, 5-aminosalicylic acid) and drugs that target mast cells re-main to be established.

Melatonin, 3 mg/d, taken at bed-time for 2 weeks seemed to be of some benefit in patients with IBS; the Irritable Bowel

Syndrome: Rational Therapy

CLINICAL HIGHLIGHTS

❑ Testing is not needed to diagnose irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) unless an “alarm” sign or symptom that may signal more serious structural disease is present. Examples of such symptoms include disease onset at age 50 years or later; recurrent vomiting; fever; and evidence of blood, pus, or excess fat in the stool.

❑ Keep in mind that there is a robust placebo response (about 30%) in patients with IBS. Reassurance, education, and a positive diagnosis help maximize the placebo response.

❑ Adding fiber to the diet can be particularly helpful in patients who have IBS with constipation. Consider prescribing a commercial fiber supplement at a starting dosage of about 3 g/d, which can be increased every 1 to 2 weeks until a dosage of about 15 g/d is reached. Keep in mind that fiber may worsen gas and bloating.

❑ Advise patients who have IBS with diarrhea to avoid artificial sweeteners, which can cause osmotic diarrhea. Avoiding high-fat foods may also prove helpful to some patients, since these can increase gas and cause dyspepsia, as well as aggravate diarrhea. Some patients with IBS are lactose-intolerant and may benefit from limiting their

consumption of milk products. A low FODMAP diet (reduce fructose, fructans, sorbitol, and raffinose) may help a subset.

❑ There is some evidence that peppermint oil can help relieve abdominal pain in IBS and that probiotic therapy can help reduce bloating. The role of other alternative therapies in IBS is unclear. ❑ Patients with IBS often are referred to surgeons and as a result may end up having unnecessary operations, such as a cholecystectomy, appendectomy, or hysterectomy. Patients may experience temporary relief after such procedures, but IBS symptoms almost invariably return.

products may be effective, as was shown in one trial of Chinese herbal medicine.34 Relaxation therapy—in-cluding progressive relaxation, mas-sage, and yoga—might help, but data are lacking.21

Psychological treatments, in-cluding hypnotherapy, cognitive be-havioral therapy, and psychotherapy, do seem to be of benefit to patients with IBS, including improving gen-eral well-being.16,35 Unfor tunately, the availability of such therapies spe-cifically targeting IBS is limited.

CREATING A

MANAGEMENT PLAN

Good management plans for IBS have clear and realistic goals to which both the patient and clinician are com-mitted. Such agreed-on goals might include symptom reduction (but not elimination) and improved well-being. Some patients need little besides good dietary advice and general health tips (see Table 4). Because no FDA-approved drug is disease-modifying, use medications judiciously to treat symptom exacerbations.

Some patients may want to seek more information on the Internet. Both good and very bad information on IBS can be found on the World Wide Web. For those who wish to avail themselves of this resource, I explain during a consultation the dif-ference between testimonials and evi-dence and I strongly encourage them to discuss their search with me.

Patient self-help groups such as the International Foundation for Functional Gastrointestinal Disor-ders (IFFGD) (www.IFFGD.org) are a great resource. Some excellent books are also available. The Func-tional Gastrointestinal Disorders

is written for patients and available

on Amazon.21 ■

REFERENCES:

1. Talley N, Spiller RC. Irritable bowel syndrome: A little understood organic bowel disease? Lancet. 2002;360:555-564.

2. Longstreth GF, Thompson WG, Chey WD, et al. Functional bowel disorders. Gastroenterology.

2006;130:1480-1491.

3. Schmulson M, Chang L. Review article: the treatment of functional abdominal bloating and dis-tension. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33(10): 1071-86.

4. Saito Y. The role of genetics in IBS. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2011;40(1):45-67.

5. Rey E, Talley NJ. Irritable bowel syndrome: novel views on the epidemiology and potential risk factors. Dig Liver Dis. 2009;41(11):772-80.

6. Ghoshal UC, Ranian P. Post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome: the past, the present and the future.

J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;26(suppl 3):94-101.

7. Ohman L, Simren M. Pathogenesis of IBS: role of inflammation, immunity and neuroimmune interactions. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;7(3):163-73.

8. Walker MM, Talley NJ, Prabhakar M, et al. Duodenal mastocytosis, eosinophilia and intraepi-thelial lymphocytosis as possible disease markers in the irritable bowel syndrome and functional dyspepsia. APT. 2009;29:765-73.

9. Barbara G, Stanghellini V, De Giorgio R, et al. Activated mast cells in proximity to colonic nerves correlate with abdominal pain in irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:693-702.

10. Camilleri M, Talley NJ. Pathophysiology as a basis for understanding symptom complexes and therapeutic targets. Neurogastroenterol Motil.

2004;16:135-142.

11. Choung RS, Ruff KC, Malhotra A, et al. Clinical predictors of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth by duodenal aspirate culture. APT. 2011;33:1059-67

12. Pimentel M, Chow EJ, Lin HC. Normalization of lactulose breath testing correlates with symptom improvement in irritable bowel syndrome. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study.

Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:412-419.

13. Pimentel M, Park S, Mirocha J, et al. The effect of a nonabsorbed oral antibiotic (rifaximin) on the symptoms of the irritable bowel syndrome.

Ann Intern Med. 2006;145:557-563.

14. Naliboff BD, Berman S, Suyenobu B, et al. Longitudinal change in perceptual and brain activa-tion response to visceral stimuli in irritable bowel syndrome patients. Gastroenterology. 2006;131: 352-365.

15. Elenkov IJ, Iezzoni DG, Daly A, et al. Cytokine dysregulation, inflammation and well-being.

Neuroimmunomodulation. 2005;12:255-269.

16. An Evidence-Based Position Statement on the Management of Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:S1-S35.

17. Limsui P, Pardi PS, Camilleri M, et al. Symp-tomatic overlap between irritable bowel syndrome and microscopic colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis.

2007;13:175-181.

surgery in irritable bowel syndrome: time to stem the flood now? Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1899-1903.

21. Talley NJ. Conquering Irritable Bowel Syndrome.

Lewiston, NY: BC Decker Inc; 2005.

22. Shepherd SJ, Parker FC, Muir JG, Gibson PR. Dietary triggers of abdominal symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome: randomized placebo-controlled evidence. Clin Gastro Hep.

2008;6:765-771.

23. Biesiekierski JR, Newnham ED, Irving PM, et al. Gluten causes gastrointestinal symptoms in subjects without celiac disease: a double-blind ran-domized placebo-controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol.

2011;106:508-514.

24.Chiarioni G, Salandini L, Whitehead WE. Biofeedback benefits only patients with outlet dys-function, not patients with isolated slow transit constipation. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:86-97.

25. Schey R, Rao SS. Lubiprostone for the treat-ment of adults with constipation and irritable bowel syndrome. Dig Dis Sci. 2011 (in press).

26. Chang L, Chey WD, Harris L, et al. Incidence of ischemic colitis and serious complications of constipation among patients using alosetron: sys-tematic review of clinical trials and post-marketing surveillance data. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101: 1069-1079.

27. Pimentel M, Lembo A, Chey WD, et al. Rifaximin Therapy for Patients with Irritable Bowel Syndrome without Constipation. N Engl J Med.

2011;364:22-32.

28. Drossman D, Toner BB, Whitehead WE, et al. Cognitive-behavioral therapy versus education and desipramine versus placebo for moderate to severe functional bowel disorders. Gastroenterology. 2003; 125:19-31.

29. Whorwell PJ, Altringer L, Morel J, et al. Efficacy of an encapsulated probiotic Bifidobacterium infantis

35624 in women with irritable bowel syndrome.

Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1581-1590.

30. Chitkara DK, Bredenoord AJ, Talley NJ, Whitehead WE. Aerophagia and rumination: recog-nition and therapy. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol.

2006;9:305-313.

31. Choung RS, Locke GR, Zinmeister AR, et al. Opioid bowel dysfunction and narcotic bowel syn-drome: a population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol.

2009;104:199-204.

32. Song GH, Leng PH, Gwee KA, et al. Melatonin improves abdominal pain in irritable bowel syndrome patients who have sleep disturbances: a randomised, double blind, placebo controlled study. Gut. 2005;54:1402-1407.

33. Saito YA, Rey E, Almazar-Elder AE, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of St John’s wort for treating irritable bowel syn-drome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:170-177.

34. Bensoussan A, Talley NJ, Hing M, et al. Treatment of irritable bowel syndrome with Chinese herbal medicine: a randomized contolled trial. JAMA. 1998;280:1585-1589.

35. Gonsalkorale WM, Whorwell PJ. Hypnotherapy in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;17:15-20.

36. Talley NJ, ed. Clinical Gastroenterology. 3rd ed. Sydney, Australia: Elsevier 2010.