Pancreaticoduodenectomy in Elderly Adults: Is It Justified in

Terms of Mortality, Long-Term Morbidity, and Quality of Life?

Fabian Gerstenhaber, MD,*

†Julie Grossman, MD,* Nir Lubezky, MD,*

†Eran Itzkowitz, MD,*

†Ido Nachmany, MD,*

†Ronen Sever, MD,*

‡Menahem Ben-Haim, MD,*

†Richard Nakache, MD,*

†Joseph M. Klausner, MD,*

†and Guy Lahat, MD*

†OBJECTIVES: To evaluate long-term morbidity, mortal-ity, and quality of life (QoL) after pancreaticoduodenecto-my (PD) in elderly adults.

DESIGN: Retrospective cohort study.

SETTING: Tel-Aviv Sourasky Medical Center, Tel-Aviv, Israel.

PARTICIPANTS: One hundred and sixty-eight individuals aged 70 and older who underwent PD between 1995 and 2010.

MEASUREMENTS: A prospective pancreatic surgery

database was analyzed for postoperative morbidity; mor-tality; intensive care unit (ICU), hospital, and rehabilita-tion facility stay; and readmissions after surgery. QoL was assessed using a validated questionnaire completed 3, 6, and 12 months after surgery.

RESULTS: Seventy-two percent of the participants had an American Society of Anesthesiologists score of 3 or greater. There was no intraoperative death. Thirty- and 60-day postoperative mortality rates were 5.9% and 6.5%, respectively. Median ICU stay was 2 days, and median hospital stay was 22 days. Sixty-four participants (37.5%) were discharged to a rehabilitation facility. The first-year readmission rate was 31%. One- and 2-year overall survival rates were 58% and 36%, respectively. Global QoL scores 3 and 12 months after surgery were 68% and 73%, respectively. Scores were lower yet compa-rable with those of matched individuals undergoing lapa-roscopic cholecystectomy.

CONCLUSION: Most elderly adults with pancreatic can-cer survive longer than 1 year after PD; 36% survive longer than 2 years. These individuals are likely to have acceptable long-term morbidity and overall good QoL, corresponding with their age.J Am Geriatr Soc 61:1351–1357, 2013.

Key words: pancreaticoduodenectomy; elderly; mortal-ity; long-term morbidmortal-ity; quality of life

P

ancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) is being performed in increasing numbers for various malignant and prema-lignant pathologies in all age groups and in the presence of considerable comorbidity.1–4 The significant reduction in perioperative morbidity (40%) and mortality (2%), mostly attributed to the growing experience in high volume referral centers for pancreatic surgery, can explain this trend.5–9Because of demographic changes in the United States, the proportion of the elderly population is rapidly increas-ing. By 2025, 20% of all Americans will be aged 65 and older, compared with 12% of the current population.10 Given that the incidence of cancer increases with age, the burden of cancer is anticipated to increase as well,11so the number of elderly adults diagnosed with and surgically treated for pancreatic cancer is also likely to increase.

It was recently shown that, regardless of their perfor-mance status, significant comorbidities, and how aggressive their disease is, properly selected elderly adults with pancreatic cancer benefit from surgery.12,13 These results support previous data.9,13–17 Two studies demonstrated that, even in individuals aged 80 and older, PD can be per-formed safely and that age alone should not be a contrain-dication to pancreatic resection.9,18 Overall, long-term survival of elderly adults after PD for pancreatic cancer significantly exceeds estimated median survival by approxi-mately 6 months over that of those who do not undergo surgery.17–19 Nevertheless, there are no data concerning long-term morbidity and quality of live (QoL) in this pop-ulation. Given their poor physiological and psychosocial reserves, the aim of the current study was to evaluate the rehabilitation process of elderly adults and their QoL after PD. The a priori hypothesis, based on clinical experience, was that, although the rehabilitation process is longer for this population, their QoL is very good.

From the *Department of Surgery, Tel-Aviv Sourasky Medical Center,

†Sackler School of Medicine, Tel-Aviv University, and‡Department of

Orthopedic Surgery, Tel-Aviv Sourasky Medical Center, Tel-Aviv, Israel. Address correspondence to Fabian Gerstenhaber, Department of Surgery, Tel-Aviv Sourasky Medical Center, 6 Weitzman Street, Tel-Aviv, Israel. E-mail: fabian.ger@gmail.com

DOI: 10.1111/jgs.12360

JAGS 61:1351–1357, 2013

©2013, Copyright the Authors

METHODS

Participants and Methods

The Sourasky Medical Center institutional review board approved the study. A waiver of consent was granted for the proposed patient record review. Searching the pancreatic surgery database, individuals aged 70 and older who underwent PD from January 1995 to March 2010 were identified (n=190), and their medical records were reviewed. Individuals with metastatic disease or incomplete data were excluded (n =22). The final study cohort consisted of 168 participants. All participants remained in active clinical follow-up through the outpatient clinic.

Evaluation methods for clinical determinations of inter-est included various radiographic (e.g., computed tomogra-phy, magnetic resonance imaging, positron emission tomography, ultrasound) and clinical examinations. Some participants were treated with systemic chemotherapy with or without radiation in accordance with the physician rec-ommendations of the multidisciplinary planning conference. The recommendations for surgical, chemotherapeutic, and radiation treatments were based on an evaluation of clinical prognostic factors. Surgical technique was standardized with systematic lymphadenectomy. Individuals who had partial resection of the superior mesenteric vein, portal vein, or both were included in the study cohort. Pyloric preserva-tion was performed in the minority of cases (n= 10), in accordance with the individual surgeon’s preference. The individuals who underwent pyloric preserving were not included in the QoL study cohort.

Quality of life was evaluated using the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Quality of Life Questionnaire-Core 36 (QLQ-C30), a standardized cancer-specific questionnaire20 that includes functional scales, symptom scales, a global health and general QoL scale, items assessing symptoms that indi-viduals with cancer commonly report (dyspnea, loss of appetite, insomnia, constipation, diarrhea), and the per-ceived financial effect of the disease. All EORTC QLQ-C30 items have response categories with four levels, rang-ing from not at all (score = 1) to very much (score = 4), apart from the two items for overall physical condition and overall QoL, which have 7-point response categories ranging from very poor to excellent. High functional scale scores represent good or healthy levels of functioning, and high symptom scores represent high levels of symptoms or problems. The results are expressed as percentages and means. The EORTC QLQ-C30 was administered over the telephone 3, 6, and 12 months after surgery. Elderly adults who underwent PD who had malignant or premalignant pathology with recurrent disease during the first year after surgery were excluded from the QoL data analysis.

Quality of life of the two main participant groups was compared: individuals who underwent PD versus matched (sex, age, and comorbidities included within the Charlson Index) individuals who underwent laparoscopic cholecys-tectomy (LC) who had an uneventful postoperative course. Individuals who underwent PD were further categorized into those who had surgery for benign or premalignant pathology and those who had malignant pathology, and QoL was similarly compared in all domains.

Clinical and demographic characteristics, QoL physi-cal domain, psychologiphysi-cal domain, global health, and glo-bal QoL of the main groups and the subgroups were compared.

The following preoperative clinical and pathological features were included in the analysis: sex, age, ASA score, clinical presentation, preoperative diabetes mellitus, preoperative anemia, and type of diagnostic evaluation. All participants were evaluated using at least one imaging modality before surgery (ultrasound, computed tomogra-phy, endoscopic ultrasound, or endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreaticography). Intraoperative findings eval-uated were type of pancreatic resection, number of packed red blood cell units consumed, and length of operation.

Postoperative characteristics assessed were postopera-tive complications, perioperapostopera-tive mortality, length of inten-sive care unit (ICU) stay, length of hospital stay, discharge to rehabilitation facility, rehabilitation length of stay, and hospital readmission. Postoperative complications like sepsis, pancreatic fistula, major bleeding, renal failure, and reoperation were included in the analysis. Pancreatic fistula was defined as the occurrence of more than 30 mL of amylase-rich fluid from drains on Postoperative Day 7 or upon discharge with surgical drains in place regardless of amount. Perioperative mortality was defined as in-hospital death within 30 days after surgery.

Data concerning microscopic margins of resection, histological type, tumor grade, and lymph node involve-ment were obtained from the pathology reports.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS for Windows version 17 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL). Distributions and frequencies of medical data were compared. Scoring of the EORTC QLQ-C30 and the pancreatic cancer module scales were performed according to the EORTC-QLQ-C30 scoring manual.21 Raw scores were transformed linearly to give a range from 0 to 100; a score of 1 to 15 represented very poor overall QoL or global health, and a score of 85 to 100 represented excellent overall QoL or global health.22 Scales were calculated if the participant completed at least half of the items. Because the QoL data were not normally distributed, nonparametric methods were used for statisti-cal analysis. QoL analysis comparing two groups was performed using the Mann–Whitney U test. A global two-tailedP>.05 was considered to be statistically signifi-cant, and a mean difference of at least 10 points on the QoL scales was considered clinically relevant.23 Survival analyses were performed using the Kaplan–Meier method. RESULTS

Participant and Tumor Characteristics

One hundred and sixty-eight individuals aged 70 and older who underwent PD between 1995 and 2010 were included in this study cohort. Participant and tumor characteristics are depicted in Table 1.

Median age at the time of diagnosis was 75 (range 70–87); there were 69 men (41%) and 99 women (59%).

One hundred and twenty-four participants (74%) had an American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score of 3 or higher; cardiovascular comorbidities (hypertension, ische-mic heart disease, previous myocardial infarction, and previous cerebrovascular accident) accounted for 62% of the total documented conditions, whereas significant respiratory or renal insufficiency accounted for less than 15%. Preoperative anemia (hemoglobin <11 g/dL) was found in 11% of participants. Jaundice was the presenting symptom in 101 participants (60%); 57 participants (34%) were stented using endoscopic retrograde cholangi-ography before surgery. One hundred and twenty-eight participants (76%) had PD for invasive cancer, and pan-creatic ductal adenocarcinoma was the most common histology (n=82, 49%); 36 of these (44%) had lymph node metastases, and positive margins were documented in 12 (15%).

Treatment and Outcome Characteristics

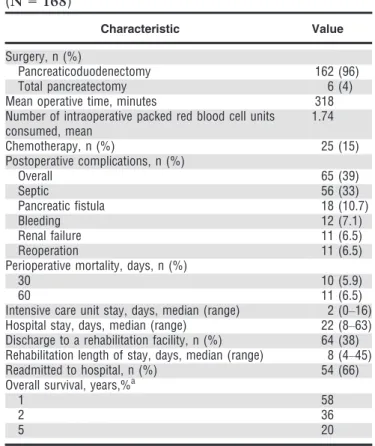

All 168 participants included in the study cohort had com-plete macroscopic resection at the Tel-Aviv Sourasky Med-ical Center. Table 2 depicts their treatment and outcomes. One hundred and sixty-two participants (96%) underwent PD and six (4%) underwent total pancreatectomy. Ten of the individuals who underwent PD (6%) underwent pylo-rus-preserving PD.

Mean operative time was 318 minutes (standard error (SE) 67 minutes), and mean number of packed red blood cell units consumed during the operation was 1.74 (SE 2.2). There were no intraoperative deaths; 30- and 60- day post-operative mortality rates were 5.9% (n=10) and 6.5% (n =11), respectively. Seven participants developed multi-organ failure after septic complications, three died from pulmonary embolism and one from hemorrhagic shock followed by acute myocardial infarction and multiorgan failure.

Ninety-four participants (56%) were admitted to the ICU after surgery, some because of surgeon preference and some because of surgical complications; their median ICU stay was 2 days (range 0–16 days). Median postoperative hospital length of stay was 22 days (range 8–63 days). Overall complication rate was 39% (n =65), most of which was from sepsis (33%, n =56); other complications included were intraabdominal abscess formation, anasto-motic leak, deep wound infection, pneumonia, and line sepsis. Eleven participants (6.5%) were reoperated, seven because of bleeding. Sixty-four participants (38%) were discharged to a rehabilitation facility and had a median length of stay of 8 days (range 4–45 days).

Fifty-four participants (32.1%) were readmitted to the hospital during the first year after surgery, and 14 of these (25.9%) were readmitted more than once. The most common reason for hospital readmission during the first year was disease progression (n =21, 38.9%); 17 partici-pants (31.4%) were readmitted for surgery-related compli-cations. Median follow-up for the entire cohort was 32 months; overall 1-, 2-, and 5-year survival of partici-Table 1. Clinical and Pathological Characteristics

(N = 168)

Characteristic Value

Age, median (range) 75 (70–87)

Sex, n (%)

Male 69 (41)

Female 99 (59)

American Society of Anesthesiologists score, n (%)

1–2 37 (22)

≥3 124 (74)

Unknown 7 (4)

Jaundice, n (%) 101 (60)

Preoperative diabetes mellitus, n (%) 52 (31) Diagnostic evaluation, n (%)

Tomography 143 (85)

Ultrasound 64 (38)

Endoscopic ultrasound 91 (54)

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography 57 (34) Preoperative anemia (hemoglobin<11 g/dL), n (%) 18 (11)

Invasive cancer, n (%) 128 (76)

Histology

Ductal adenocarcinoma, n (%) 82 (49)

Tumor size, cm, mean (standard error) 2.9 (0.33)

Well differentiated, n (%) 10 (12)

Moderate differentiated, n (%) 60 (74)

Poorly differentiated, n (%) 12 (14)

Positive lymph nodes, n (%) 36 (44)

Positive margins, n (%) 12 (15)

Papillary carcinoma, n (%) 30 (18)

Cholangiocarcinoma, n (%) 10 (6)

Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm, n (%) 25 (15)

Mucinous cystic neoplasm, n (%) 6 (4)

Neuroendocrine tumor, n (%) 2 (1)

Other, n (%) 13 (7)

Table 2. Treatment and Outcome Characteristics

(N = 168)

Characteristic Value

Surgery, n (%)

Pancreaticoduodenectomy 162 (96)

Total pancreatectomy 6 (4)

Mean operative time, minutes 318

Number of intraoperative packed red blood cell units consumed, mean 1.74 Chemotherapy, n (%) 25 (15) Postoperative complications, n (%) Overall 65 (39) Septic 56 (33) Pancreatic fistula 18 (10.7) Bleeding 12 (7.1) Renal failure 11 (6.5) Reoperation 11 (6.5)

Perioperative mortality, days, n (%)

30 10 (5.9)

60 11 (6.5)

Intensive care unit stay, days, median (range) 2 (0–16)

Hospital stay, days, median (range) 22 (8–63)

Discharge to a rehabilitation facility, n (%) 64 (38) Rehabilitation length of stay, days, median (range) 8 (4–45)

Readmitted to hospital, n (%) 54 (66)

Overall survival, years,%a

1 58

2 36

5 20

pants who underwent PD for ductal adenocarcinoma were 58%, 36%, and 20%, respectively.

Quality of Life

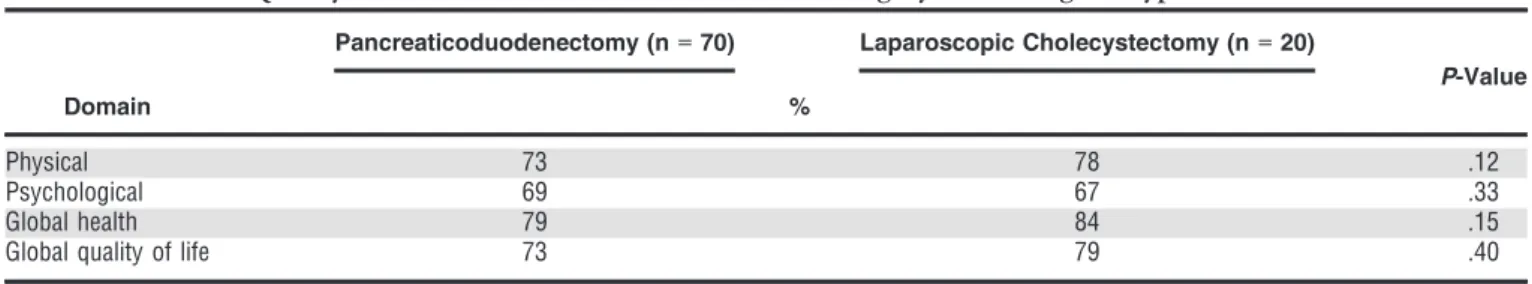

Quality of life was assessed in 70 elderly adults who underwent PD who were free of disease in the first year after surgical resection; 53 of these (75.7%) had surgery for malignant tumors and 17 (24.3%) for premalignant or benign pathology. QoL scores of all individuals who underwent PD were compared with those of 20 matched individuals who underwent LC. Overall QoL scores 6 months or more after surgical resection of both study groups are shown in Table 3. QoL scores in the physical and psychological domains of individuals who underwent PD were 73% and 69%, respectively. Global health and global QoL scores were 79% and 73%, respectively. These scores did not significantly differ from scores in the LC group: 78% (P=.12), 67% (P= .33), 84% (P= .15), and 79% (P=.40), respectively, although over the first 3 months, individuals who underwent PD reported more fatigue (75% vs 13%, p =.02), loss of efficiency (70% vs 20%, P= .05), weight loss (51% vs 0%, P=.02), pain (35% vs 10%, P= .05), nausea and vomiting (68% vs 10%,P=.01), and diarrhea (29% vs 5%,P=.04).

When evaluating functional, symptom, and global QoL scales from day of discharge to 12 months after surgery, individuals who underwent PD showed constant improvement in all three categories. Owing to the large number of items included in the QoL questionnaires, only selected scales are graphically presented (Figure 1). Unlike emotional functioning, which improved gradually over 12 months and did not reach a plateau, role functioning improved rapidly over the first 3 months, reaching a plateau 6 months after surgery (Figure 1A). Fatigue was the most common symptom that participants who under-went PD reported; it was a highly significant symptom throughout the first 6 months after surgery and improved significantly thereafter (Figure 1B).

Figure 1C illustrates that global health and global QoL improved considerably over the first 3 months after surgery, although global health reached a plateau after 6 months, whereas global QoL scores did not.

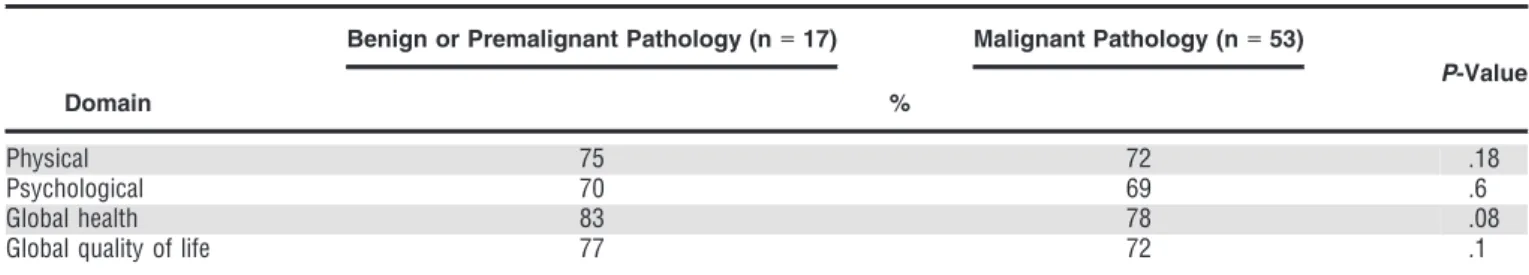

QoL Assessment According to PD Subgroup

Individuals who underwent PD were subcategorized into those who had surgery for malignant pathology (n=53) and those who had surgery for benign or premalignant

pathology (n=17). Their QoL scores 6 months or more after surgical resection are shown in Table 4.

Quality of life score was 72 for the malignant pathol-ogies and 69 for the benign or premalignant patholpathol-ogies in the physical domain and 75 for the malignant pathologies and 70 for the benign or premalignant in the psychosocial domain (P>.05). As shown in Table 4, global health and global QoL scores did not differ significantly between the PD subgroups.

DISCUSSION

Long-term outcomes and survival for individuals with pancreatic cancer are poor.10,11,19 Nevertheless, an aggres-sive multidisciplinary therapeutic approach including radical surgical resection and systemic chemotherapy for select individuals is the only potentially curative treatment, albeit with high risk of perioperative morbidity and mortality.2,13,15,16Perioperative mortality ranges from 4.3% to 6%. In the present series, 30- and 60-day postoperative mortality were 5.9% and 6.5%, respectively; morbidity was 39%. These rates are higher than post-PD mortality reported in younger cohorts,6,24–26although this is concor-dant with the advanced age (median 75 vs 61 and 64.3) and high proportion of participants with an ASA score of 3 or greater (74% vs 9–34%) included in the current study.13,15,16 More than half of participants undergoing PD stayed in a surgical ICU after surgery, and their median ICU length of stay was 2 days (range 0–16 days). In a subset analysis, elderly adults were more likely than those younger than 70 to be admitted to the ICU even if the surgery was uneventful. This trend reflects individual surgeon preference, rather than adherence to clear clinical institutional guidelines.

In contrast to previous reports,9 elderly adults who underwent PD included in the present series had a long hospital stay (mean 22 days, range 8–63); practice varia-tion oriented toward a long hospital stay and individual surgeons’ predilection for a more-conservative, prudent approach may similarly explain this, although there is an additional explanation. The data show that almost two-thirds of these individuals were not discharged to a reha-bilitation facility for various reasons (e.g., patient prefer-ence, declination by institutional or external rehabilitation programs), so the majority continued their postoperative recovery process in the surgical department before discharge home.

These data support recent reports12,15,17,18 showing that mortality and morbidity after PD in elderly adults are

Table 3. Overall Quality of Life Assessment>6 months After Surgery According to Type of Procedure

Domain

Pancreaticoduodenectomy (n=70) Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy (n=20)

P-Value %

Physical 73 78 .12

Psychological 69 67 .33

Global health 79 84 .15

Global quality of life 73 79 .40

Figure 1.Quality of Life Questionnaire-Core 36 (QLQ-C30) scales for functional (A), symptom (B), and global health and qual-ity of life (C). High scores present represent good or healthy levels of functioning, whereas high symptom scores represent high

levels of symptoms or problems. EORTC=European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer.

Table 4. Quality-of-Life Assessment According to Pancreaticoduodenectomy Subgroup>6 Months After Surgery

Domain

Benign or Premalignant Pathology (n=17) Malignant Pathology (n=53)

P-Value %

Physical 75 72 .18

Psychological 70 69 .6

Global health 83 78 .08

Global quality of life 77 72 .1

acceptable and that surgical resection can usually be per-formed safely. In spite of these repetitive observations, pri-mary care physicians and gastroenterologists may hesitate to refer their elderly patients for surgery. Such hesitation may also be because of the physician’s and the individual’s desire to preserve quality of life rather than to prolong life. Evidence showing recovery to normal QoL after PD in elderly adults may simplify the decision to recommend sur-gery for this frail population.

There are few comprehensive QoL studies of individu-als who have undergone PD, and these were based on younger cohorts and therefore may not represent results in older adults. In a cross-sectional survey comparing 25 indi-viduals who underwent PD, with 25 age- and sex-matched individuals undergoing LC, QoL was assessed using six instruments, all of which indicated near-normal well-being, and no instrument revealed significant differences between the individuals who underwent PD and control partici-pants.27 An additional aspect of this study found normal nutritional status and a return to preoperative body weight in the individuals who underwent PD. Furthermore, the largest single-institution experience assessing QoL after PD found that, as a group, individuals who survived surgery had near-normal QoL scores.25 Most participants had QoL scores comparable with those of control participants and could perform daily activities independently.

To the best of the knowledge of the authors of the current study, this study is the first to report QoL after PD in the elderly population. The present cohort represents the current population of elderly undergoing PD in a high-volume referral center for pancreatic surgery.

The data analysis included three subgroups: elderly adults undergoing PD for malignant pathology (n=53) and for benign or premalignant pathology (n=17) and a control subgroup of elderly adults undergoing LC (n=20). Elderly adults undergoing LC recovered faster than those undergoing PD, although the data show that, within 3 months after surgery, QoL scores of individuals who underwent PD in all domains were comparable with those of their matched LC controls. Individuals who underwent PD who had surgery for malignant pathology did worse with respect to global health and global QoL than those with benign or premalignant pathology. Most were not treated with chemotherapy, so adjuvant systemic treatment is not a potential explanation. It was presumed that an emotional effect may play a role, although QoL scores in the psychological domain were similar in both PD groups. It is possible that elderly adults who underwent PD for malignant pathology had lower physiological reserves to begin with than their counterparts with nonmalignant pathology, but such data were not included in the database. In concordance with expectations, a gradual rather than rapid recovery process was found in all elderly adults who underwent PD included in this study. According to observations, most participants reported normal or near-normal global health and global QOL 3 months after surgery. Similarly, within this time period, elderly adults who underwent PD were likely to have normal role functioning, experience less pain, and have normal bowel movements. Despite normal role functioning, fatigue was common in these participants, lasting for 3 to 6 months after surgery. Also, in contrast to the quick return to normal role

functioning, it seems that emotional recovery after PD in elderly adults is longer and almost linear through the first year after surgery, at which time, most participants reported full return to normal emotional functioning. A higher prevalence of postoperative depression observed in the elderly population after major surgery than in individu-als younger than 70 can explain this phenomenon.28,29

The present study has some methodological limita-tions. Although the data were collected prospectively, the analysis was made retrospectively, and there was no infor-mation on preoperative QoL. These data were collected over a long period of time, during which there were changes in clinical care, new techniques, and new medica-tions. In terms of participant selection, the exclusion of individuals who had recurrent disease during the first year after surgery and the selection of the subgroups of partici-pants to assess QoL could have led to selection bias, which needs to be recognized as a limitation of the study. CONCLUSION

Despite significant comorbidities and low physiological reserves, elderly adults with pancreatic cancer benefit from surgery. Despite higher rates of postoperative morbidity and mortality and lower overall survival rates, PD in elderly adults prolongs life with a quick return to normal functioning and normal QoL. This study should encourage physicians to consider PD as a mainstay of therapy in elderly adults. Additional studies incorporating preopera-tive and serial postoperapreopera-tive QoL assessment in this popu-lation are needed.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was presented at the Society of Surgical Oncol-ogy’s 64th Annual Cancer Symposium, March 2–5, 2011, San Antonio, Texas.

Conflict of Interest: The editor in chief has reviewed the conflict of interest checklist provided by the authors and has determined that the authors have no financial or any other kind of personal conflicts with this paper.

Author Contributions: Study concept and design: Fabian Gerstenhaber, Julie Grossman, Nir Lubezky, Eran Itzkowitz, Ido Nachmany, Menahem Ben-Haim, Richard Nakache, Joseph M. Klausner, Guy Lahat. Acquisition of subjects and data: Fabian Gerstenhaber, Eran Itzkowitz, Ronen Sever, Joseph M. Klausner, Guy Lahat. Analysis and interpretation of data: Fabian Gerstenhaber, Eran Itzkowitz, Joseph M. Klausner, Guy Lahat. Preparation of manuscript: Fabian Gerstenhaber, Julie Grossman, Eran Itzkowitz, Menahem Ben-Haim, Richard Nakache, Joseph M. Klausner, Guy Lahat.

Sponsor’s Role:There was no sponsor for this paper. REFERENCES

1. Kawai M, Yamaue H. Analysis of clinical trials evaluating complications after pancreaticoduodenectomy: A new era of pancreatic surgery. Surg Today 2010;40:1011–1017.

2. Billings BJ, Christein JD, Harmsen WS et al. Quality-of-life after total pan-createctomy: Is it really that bad on long-term follow-up? J Gastrointest Surg 2005;9:1059–1066; discussion 1066–1057.

3. Conlon KC, Klimstra DS, Brennan MF. Long-term survival after curative resection for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Clinicopathologic analysis of 5-year survivors. Ann Surg 1996;223:273–279.

4. Sohn TA, Yeo CJ, Cameron JL et al. Resected adenocarcinoma of the pancreas-616 patients: Results, outcomes, and prognostic indicators. J Gastro-intest Surg 2000;4:567–579.

5. Kotwall CA, Maxwell JG, Brinker CC et al. National estimates of mortal-ity rates for radical pancreaticoduodenectomy in 25,000 patients. Ann Surg Oncol 2002;9:847–854.

6. Diener MK, Knaebel HP, Heukaufer C et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of pylorus-preserving versus classical pancreaticoduodenecto-my for surgical treatment of periampullary and pancreatic carcinoma. Ann Surg 2007;245:187–200.

7. Strasberg SM, Drebin JA, Soper NJ. Evolution and current status of the Whipple procedure: An update for gastroenterologists. Gastroenterology 1997;113:983–994.

8. Yeo CJ, Cameron JL, Sohn TA et al. Six hundred fifty consecutive pancrea-ticoduodenectomies in the 1990s: Pathology, complications, and outcomes. Ann Surg 1997;226:248–257; discussion 257–260.

9. Makary MA, Winter JM, Cameron JL et al. Pancreaticoduodenectomy in the very elderly. J Gastrointest Surg 2006;10:347–356.

10. Muss HB. Cancer in the elderly: A societal perspective from the United States. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2009;21:92–98.

11. Altekruse SF, Kosary CL, Krapcho M et al. Seer Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2007, National Cancer Institute [on-line]. Available at http://Seer. Cancer.Gov/Csr/1975_2007/ Accessed February 13, 2011.

12. Lahat G, Sever R, Lubezky N et al. Pancreatic cancer: Surgery is a feasi-ble therapeutic option for elderly patients. World J Surg Oncol 2011;9:10.

13. Brachet D, Lermite E, Vychnevskaia-Bressollette K et al. Should pancreati-coduodenectomy be performed in the elderly? Hepatogastroenterology 2012;59:266–271.

14. Brozzetti S, Mazzoni G, Miccini M et al. Surgical treatment of pancreatic head carcinoma in elderly patients. Arch Surg 2006;141:137–142. 15. Ballarin R, Spaggiari M, Di Benedetto F et al. Do not deny pancreatic

resection to elderly patients. J Gastrointest Surg 2009;13:341–348. 16. Scurtu R, Bachellier P, Oussoultzoglou E et al. Outcome after

pancreatico-duodenectomy for cancer in elderly patients. J Gastrointest Surg 2006;10:813–822.

17. Ito Y, Kenmochi T, Irino T et al. The impact of surgical outcome after pancreaticoduodenectomy in elderly patients. World J Surg Oncol 2011; 9:102.

18. Khan S, Sclabas G, Lombardo KR et al. Pancreatoduodenectomy for ductal adenocarcinoma in the very elderly: Is it safe and justified? J Gastrointest Surg 2010;14:1826–1831.

19. Shore S, Vimalachandran D, Raraty MG et al. Cancer in the elderly: Pancreatic cancer. Surg Oncol 2004;13:201–210.

20. Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: A quality-of-life instru-ment for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst 1993;85:365–376.

21. Fayers PM, Aaronson NK, Bjordal K et al. The EORTC QLQ-C30 Scoring Manual, 3rd Ed. Brussels: European Organisation for Research and Treat-ment of Cancer, 2001.

22. Scott NW, Fayers PM, Aaronson NK et al. EORTC QLQ-C30 Reference Values. Brussels: European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer, 2008.

23. Osoba D, Rodrigues G, Myles J et al. Interpreting the significance of changes in health-related quality-of-life scores. J Clin Oncol 1998;16: 139–144.

24. Fitzmaurice C, Seiler CM, Buchler MW et al. Survival, mortality and qual-ity of life after pylorus-preserving or classical Whipple operation. A system-atic review with meta-analysis. Chirurg 2010;81:454–471.

25. Huang JJ, Yeo CJ, Sohn TA et al. Quality of life and outcomes after pan-creaticoduodenectomy. Ann Surg 2000;231:890–898.

26. Nguyen TC, Sohn TA, Cameron JL et al. Standard vs. radical pancreatico-duodenectomy for periampullary adenocarcinoma: A prospective, random-ized trial evaluating quality of life in pancreaticoduodenectomy survivors. J Gastrointest Surg 2003;7:1–9; discussion 9–11.

27. McLeod RS, Taylor BR, O’Connor BI et al. Quality of life, nutritional sta-tus, and gastrointestinal hormone profile following the Whipple procedure. Am J Surg 1995;169:179–185.

28. Pignay-Demaria V, Lesperance F, Demaria RG et al. Depression and anxi-ety and outcomes of coronary artery bypass surgery. Ann Thorac Surg 2003;75:314–321.

29. Lyness JM, Yu Q, Tang W et al. Risks for depression onset in primary care elderly patients: Potential targets for preventive interventions. Am J Psychi-atry 2009;166:1375–1383.