AN EVALUATION OF CHANGES IN CAPITAL

INVESTMENT BY AUTOMOTIVE COMPANIES IN

PREPARATION

FOR

THE

AUTOMOTIVE

PRODUCTION

AND

DEVELOPMENT

PROGRAMME (APDP)

B.S. BACELA

ii

AN EVALUATION OF CHANGES IN CAPITAL INVESTMENT BY

AUTOMOTIVE COMPANIES IN PREPARATION FOR THE AUTOMOTIVE

PRODUCTION AND DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME (APDP)

BY

BANDILE SAKHEKILE BACELA

Treatise submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for

the degree Magister in Business Administration at the

Nelson Mandela Metropolitan Business School

December 2012

TABLE OF CONTENTS

DECLARATION ... V ABSTRACT ... VI ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ... VII

CHAPTER 1 ... 1

INTRODUCTION TO THE RESEARCH STUDY ... 1

1.1 INTRODUCTION ... 1

1.2 PROBLEM STATEMENT ... 2

1.3 IMPORTANCE OF STUDY ... 3

1.4 CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK ... 5

1.5 RESEARCH QUESTION ... 6

1.5.1 Primary Research Question ... 6

1.6 RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODOLOGY ... 6

1.6.1 Research Design Objectives ... 6

1.6.2 Research Methodology... 8

1.6.3 Chosen Qualitative Methodology Paradigm ... 8

1.7 SAMPLE ... 9 1.8 MEASURING INSTRUMENT ... 9 1.9 DELIMITATIONS ... 10 1.10 TERMINOLOGY ... 10 1.11 OUTLINE OF THE STUDY ... 12 1.12 SUMMARY ... 12 CHAPTER 2 ... 14 LITERATURE REVIEW ... 14 2.1 INTRODUCTION ... 14

2.2 CHANGES TO GOVERNMENT LEGISLATION ... 15

2.3 THE IMPACT OF LEGISLATION ON CAPITAL INVESTMENT ... 34

2.4 INVESTMENT IN TRAINING AND EDUCATION TO SUPPORT CAPITAL INVESTMENT ... 41

ii

CHAPTER 3 ... 43

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODOLOGY ... 43

3.1 INTRODUCTION ... 43

3.2 RESEARCH QUESTION ... 44

3.2.1 Primary Research Question ... 44

3.3 RESEARCH DESIGN ... 45 3.4 RESEARCH METHODOLOGY ... 46 3.4.1 Research Paradigm ... 47 3.4.2 Chosen Paradigm ... 48 3.5 SAMPLE ... 49 3.6 ETHICS... 51 3.7 MEASURING INSTRUMENT ... 52 3.8 SUMMARY ... 54 CHAPTER 4 ... 55

EMPIRICAL RESEARCH RESULTS AND DISCUSSIONS ... 55

4.1 INTRODUCTION ... 55

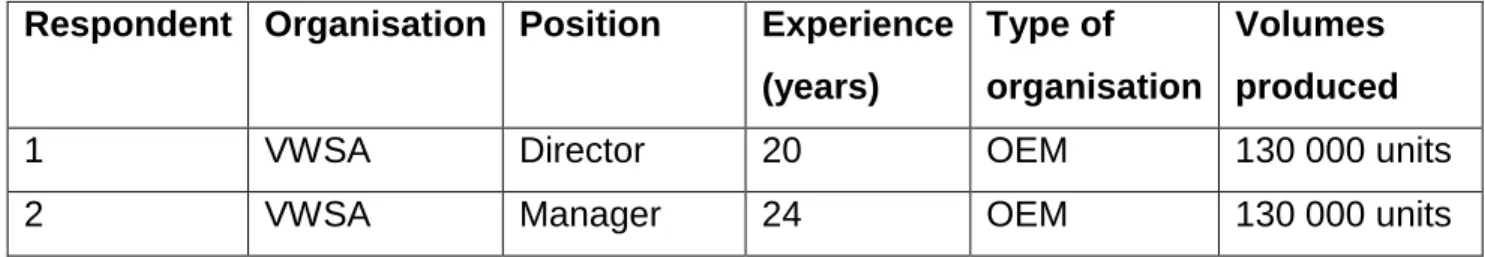

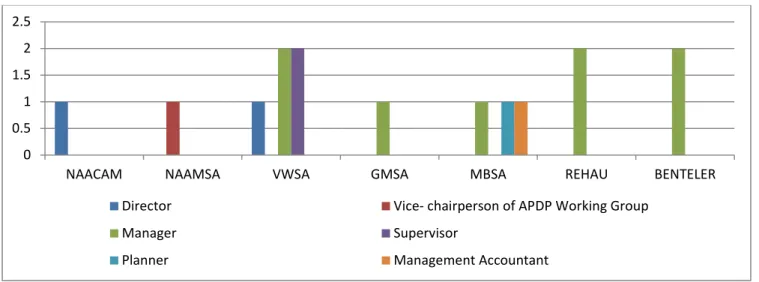

4.2 SAMPLE AND DEMOGRAPHIC SECTION ... 55

4.3 INTERVIEW QUESTIONS ... 58

4.3.1 Understanding Of Government Legislation By Industry ... 58

4.3.2 Investment In Capital In Preparation For Apdp ... 61

4.3.3 Development In People To Support Capital Investment In Preparation For Apdp 64 4.3.4 Supply Chain Management To Support Capital Investment In Preparation For Apdp ... 67

4.4 SUMMARY ... 69

CHAPTER 5 ... 71

RESEARCH SUMMARY, CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS ... 71

5.1 INTRODUCTION ... 71

5.2 RESEARCH SUMMARY ... 71

5.3 CONCLUSION ... 73

iii

REFERENCE LIST ... 80

ANNEXURE 1 - COVER LETTER ... 85

ANNEXURE 2 – INTERVIEW QUESTIONS ... 86

ANNEXURE 3 – INTERVIEW 1 ... 89

ANNEXURE 4 – INTERVIEW 2 ... 94

ANNEXURE 5 – INTERVIEW 3 ... 100

ANNEXURE 6 – INTERVIEW 4 ... 106

ANNEXURE 7 – INTERVIEW 5 AND 6 COMBINED ... 111

ANNEXURE 8 – INTERVIEW 7 ... 116 ANNEXURE 9 – INTERVIEW 8 ... 121 ANNEXURE 10 – INTERVIEW 9 ... 126 ANNEXURE 11 – INTERVIEW 10 ... 131 ANNEXURE 12 – INTERVIEW 11 ... 136 ANNEXURE 13 – INTERVIEW 12 ... 141 ANNEXURE 14 – INTERVIEW 13 ... 146 LIST OF FIGURES Figure 1: Research conceptual framework ... 5

Figure 2: The number of experts interviewed per organisation and position ... 57

Figure 3: The spread and distribution of the experts regarding their experience ... 57

Figure 4: Understanding of government legislation by industry responses ... 59

Figure 5: Responses to the investment in capital in preparation for the APDP theme questions ... 62

Figure 6: Responses to the development in people to support capital investment in preparation for APDP theme questions ... 65

Figure 7: Responses to the supply chain management to support capital investment in preparation for the APDP theme questions ... 68

Figure 8: Graphical representation of the comparison between Capital Expenditure, Domestic Production Output and employment levels represented real number and in percentages over periods 2000 - 2008 ... 75

iv

Figure 9: Projected capital expenditure and growth of total units produced over period of

year 2013 - 2020 ... 77

LIST OF TABLES Table 1: A summary of the changes to government legislation in SA (1910 – 1995) .... 15

Table 2: Import of vehicles between 1995 and 2008 ... 24

Table 3: Vehicles produced in South Africa (units) between 1995 and 2008 ... 25

Table 4: Capital Expenditure on an Annual Basis ... 29

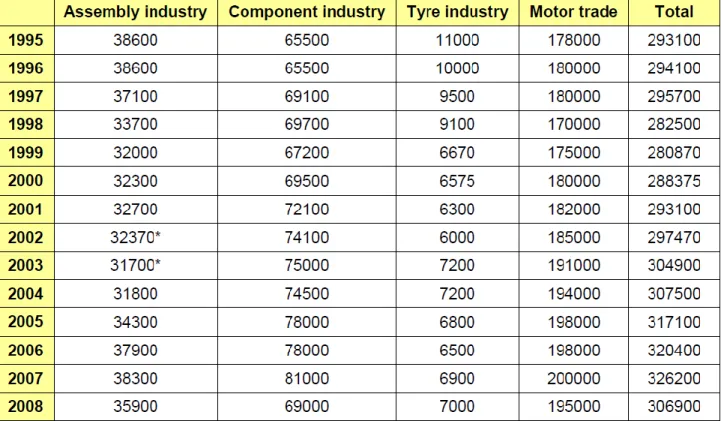

Table 5: South African automotive industry employment levels (number of employees), period year 1995 – 2008 ... 31

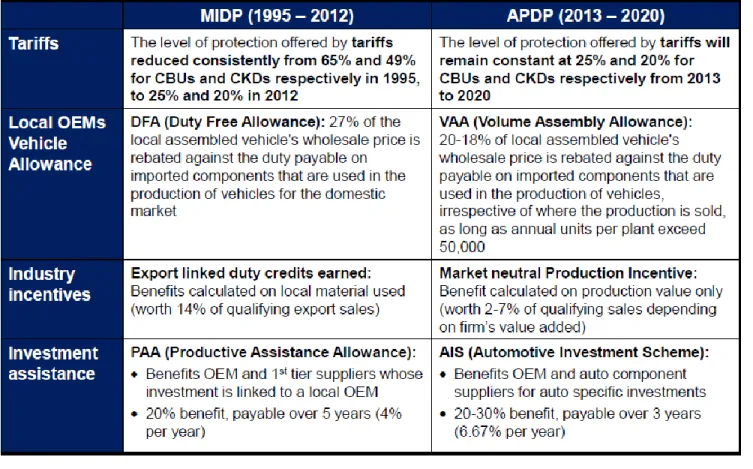

Table 6: A quick comparison between the MIDP and APDP ... 33

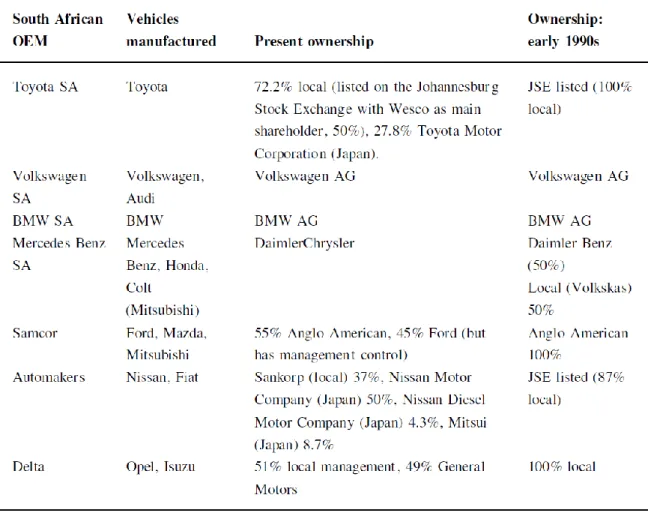

Table 7: Ownership changes at South African OEMs ... 38

Table 8: Demographic details of respondents interviewed ... 50

Table 9: Comparison between Capital Expenditure, Domestic Production Output and employment levels represented real number and in percentages over periods 2000 - 2008 ... 74

Table 10 : Correlation between capital expenditure and vehicles produced over the years 2000 – 2008... 76

v

DECLARATION

This dissertation is submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Masters in Business Administration at the Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University. This work has not been previously submitted for any other degree. The research contained in this document is as a result of my own independent work and investigation and all sources consulted have been appropriately acknowledged and referenced.

Signed:

BS Bacela

vi

ABSTRACT

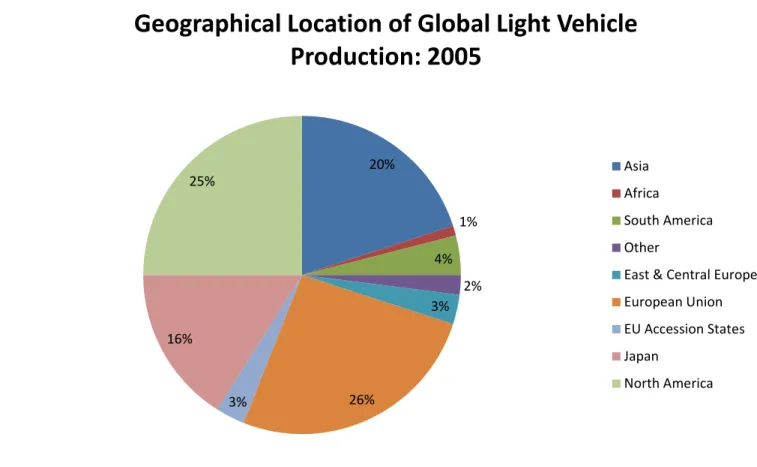

To thrive, developing countries depend on high levels of protection being given to key industries such as manufacturing; specifically the automotive and textile industries. South Africa, as a developing country and especially under the emergence of globalisation, has followed suit in terms of developing policies and structures to protect certain critical industries. During an era (1980 to 1989) of high political instability, South Africa experienced isolation from the rest of the world, which resulted in declines in industrial revenues as well as the country’s automotive industry undergoing a stage of perilous stagnation. It was through a protection regime that the automotive industry realised growth, a regime which started slowly in 1989 and accelerated in 1995 with the introduction of the Motor Industry Development Programme (MIDP) (Black, 2001).

Through this regime the South African government sought to integrate the South African automotive industry into the global market by improving the competitiveness of this industry (The DTI, 2010). This led to the automotive industry becoming one of the most successful export sectors in South African manufacturing and a large net consumer of foreign currency, totalling R20 billion and R10 billion in imports and exports respectively by 1998 (Damoense and Simon, 2004).

Reviews of the government legislation called the MIDP were held in year 1999 and 2002 and in 2008, a successor to the MIDP was named, the Automotive Production Development Programme (APDP) and is set to commence in year 2013 until 2020. Unlike its predecessor, the APDP policy promises to bring greater and more inclusive benefits to the automotive industry as a whole, provided organisations have prepared well to receive it. This study investigated whether organisations have prepared for the upcoming 2013 - 2020 APDP, with specific reference to capital investment in equipment. It determined whether automotive organisations have spent and are going to spend resources in securing equipment and technology in preparation for the introduction of the APDP.

vii

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to acknowledge Dr Siyabonga Simayi for his significant supervision, guidance and support. His patience, prodding and words of encouragement were instrumental to my completion and very much appreciated. I am particularly grateful that he allowed me to take the research direction necessary to achieve my goals and meet my own expectation.

Thanks to the loving and almighty living God who has blessed me so abundantly with family, friends and colleagues.

Special thanks to my partner for understanding when I had to wake up in the early hours to study and also for some weekends for team meetings. My son and daughters, whose presence served as a great motivation to ensure that I finish the studies within three years, thanks to you too.

An additional vote of special thanks to all the MBA colleagues with whom I have had the honour of working and the experts of the automotive industry that agreed to being interviewed, for their support and input during the data collection phase. I would not have made it without you.

I would also like to thank my company, Volkswagen Group South Africa, for sponsoring my studies.

Lastly special thanks also to Mrs Lee Kemp who edited this document, your efforts and professionalism is greatly appreciated.

1

CHAPTER 1

INTRODUCTION TO THE RESEARCH STUDY

1.1 INTRODUCTION

The South African government, having identified the automotive sector as a key driver of economic growth within the manufacturing sector with a contribution of at least 10 percent to manufacturing exports, strategically devised an industry specific policy namely the Motor Industry Development Programme (MIDP). This was done to provide stakeholders of the industry with a long term and encouraging planning horizon by means of pledging stability and certainty within the sector (The DTI, 2010; Naamsa, 2007).

Black (2002) argued that, due to a perception that exports offer great opportunities for employment, the MIDP was mainly geared towards exports, an objective it succeeded in boosting, but not necessarily growth in employment. In support of this notion Damoense and Simon (2004) agree, that even though export growth was realised as a result of this policy, the MIDP was deficient in sustaining domestic production and automotive industry employment. Even though significant gains have been observed through the MIDP, it has proven to have its short comings (Borgenheimer, 2010; Ellis, 2008).

A fundamental factor contributing to the deficiency of the MIDP has been the low levels of local content in the value chain as a result of cost pressures introduced by the liberalisation of the automotive industry. Cost pressures come as a result of foreign manufacturers offering components at prices which limit price increases to below inflation for the local component manufactures (Black, 2001). The Automotive Production Development Programme (APDP), through encouraging an increase in local value adding, seeks to ensure growth in all local levels of the automotive industry and a deepening of the supply chain (Ellis, 2008).

2

What has then become clear is the need for manufacturers (Original Equipment Manufacturers (OEMs) and component suppliers) to adjust and adopt relevant strategies in preparation of or aligning themselves to the APDP initiative. The question that this study aimed to answer was “Have the manufacturers responded in terms of their manufacturing process strategies with specific reference to capital investment in equipment?”

This ought to be done to gain maximum benefit from the introduction of the APDP, where government intends to incentivise the automotive industry to promote domestic production and job creation.

1.2 PROBLEM STATEMENT

According to Ellis (2008), all South African automotive organisations should, after the announcement of the successor to the MIDP, have begun considering and building into their adaptation strategies the implications of the APDP for their businesses. Even though it is claimed to be an improvement on the MIDP, there are fears that the APDP does not incentivise organisations to invest in labour- absorbing processes or technologies (Gaskin, 2010).

South Africa is currently in the process of phasing out the MIDP and introducing the APDP by 2013. Organisations within the automotive industry need to align with the new policy. Non-alignment could lead to non-compliance and a failure to benefit from the incentives as well as create reputational problems for the organisation. Therefore, this study investigated how an organisation can review its manufacturing process strategies with regard to its capital investment in equipment to align to the policy, so that significant benefits from the new policy are realised. The question of this study is:

“Have the players on the field of the automotive industry geared up their manufacturing processes with specific reference to capital investment in equipment, in preparation for the APDP?”

3

This study investigated whether or not introduction of legislation leads to organisations having to alter their manufacturing process strategies with specific reference to equipment. The intention of this is to ensure that manufacturers are geared up to make success a of the APDP policy and assist in sustaining domestic production and reducing unemployment as is intended by the government, through an evaluation of business strategy shifts within the automotive industry.

1.3 IMPORTANCE OF STUDY

The South African automotive industry accounts for about 10 percent of South Africa’s exports within the manufacturing sector, making it a vital player in the economy (Makapela, 2010). The automotive manufacturing industry has had to face the impact of globalisation as has the rest of the national economy, where globalisation in this context is defined as the free movement of products, technology, human resources and information across international borders. Globalisation resulted in a rapidly changing environment that has had far reaching effects on all role players, such as government, industry leaders and labour (Kingsley, 2002).

The South African government, having identified this sector as key to economic growth, in 1995 introduced the Motor Industry Development Plan (MIDP), a programme which sought to aid and support the restoration of this sector into the international value chains, export programmes and improve efficiencies (Gastrow, 2008).

The MIDP was structured in such a manner as to boost exports by enabling local vehicle manufacturers to include total export values as part of their local content total, then allowing them to import the same value of goods duty-free, while also granting a production-asset allowance to vehicle manufacturers which invest in new plants and equipment, giving them 20 percent of their capital expenditure back, in the form of import-duty credits, over a period of five years (Makapela, 2010).

The MIDP was legislated to be in effect until 2009, and to be gradually phased out by 2012. This initiative allowed for the number of base models of passenger and light

4

commercial vehicles produced by local manufacturers to be reduced from 42 prior to 1995 to 18 by 2008.This was done in order for the manufacturers to benefit from economies of scale. The average number of units per model produced went from 11 500 units in 1995 to 29 225 units in 2008 (Lamprecht, 2009).

In September 2008 the South African government announced that it is to be replaced by a programme called the Automotive Production and Development Programme (APDP). The APDP was introduced as a result of an industry review by government on the MIDP, that revealed, despite its successes, that South Africa and the sub-region remained a relatively small market in global terms, isolated from larger markets and shipping routes (Lamprecht, 2009). The government also highlighted challenges of major domestic infrastructure and logistical inefficiencies, together with severe skills shortage, among other things (Black, 2002).

The APDP serves as an affirmation of the commitment made by government through the New Growth Path (NGP) policy, to make employment creation the main criterion for economic policy. The automotive industry has been identified as one of the job drivers in the economy and therefore its policies are designed to ensure the economy becomes both competitive and more employment friendly. The APDP aims to stimulate growth in the automotive vehicle production industry from 600 000 to 1.2-million vehicles per annum by 2020 with associated deepening of the components industry. The new programme will focus on value addition while being consistent with South Africa's existing multilateral obligations (The DTI, 2010).

The Department of Trade and Industry (The DTI) claim that the new support programme will result in more jobs as well as the long-term sustainability of the industry (Makapela, 2010). But this will only be true provided the volumes require more labour and not automation, as when one considers the level of automation in global competition; for example, European OEMs being about 80 percent automated to South Africa’s 20-35 percent automation status (Jeske, 2007). This comes at a time where structural evolution is emerging in the global automotive industry, wherein collaborative engineering and production is taking place with suppliers rather than vehicle

5

manufacturers or OEMs undertaking most of the Research and Development (R&D) and production (Dannenberg & Kleinhans, 2007).

The research question asked was, will the local automotive industry players invest in capital equipment in response to the new legislation in order to become or remain competitive?

1.4 CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK

According to Sturgeon and Florida (2000), there are four areas that affect the manufacturing process in the production of vehicle and component assembly. These areas are indicated below in Figure 1, together with the area that has been considered for investigation in this study, which is denoted by means of amplification.

Figure 1: Research conceptual framework

Manufacturing process strategies Investment in processes Investment in people Supply chain management Investment in Capital

(New Facililties, Equipment and Technologies)

6

1.5 RESEARCH QUESTION

The main research question follows.

1.5.1 Primary research question

This study focused on an analysis of manufacturing process strategies and the changes within the automotive industry in anticipating the APDP. The objective of this study was to show a link between government policy (APDP) and manufacturing process strategies. Manufacturing strategies that were given consideration were with specific reference to capital investment in facilities, equipment and technologies used in manufacturing.

1.6 RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODOLOGY

It is important to be clear about how data is to be collected, thus research design objectives are discussed next.

1.6.1 Research design objectives

Research design is described as a plan according to which researchers use research participants and collect information from them in order to be able to answer questions objectively, accurately and practically. Research design that is properly planned and executed allows the researcher to rely on own observation and inferences (Clarke, 2005). The objective of this research study was to determine firm-level strategic changes in terms of manufacturing process strategies by means of investment in capital equipment as a result of the introduction of the APDP or in preparation thereof.

The first step of this study was to conduct an extensive literature review of manufacturing process strategies to compare and contrast developments, if any, after the announcement of the Motor Industry Development Plan (MIDP) successor, the APDP, towards the end of 2008. According to Ellis (2008) the South African automotive

7

industry manufacturing process strategies should, since the announcement, have indicated a certain level of organisational readiness of industry players towards the implications of APDP for their business. Thus an evaluation of how the industry players have altered their game plan in preparation for the successor (APDP) was conducted, specifically investment in capital.

To collect data, a questionnaire based on the literature review was developed and semi-structured interviews were conducted with various industry experts as respondents. The questions were used to gauge the level of understanding in automotive industry of the MIDP and APDP. Additional questions in line with organisational investment in capital in response to the aforementioned government incentive and policy were also posed.

The semi-structured interview infuses elements from both the structured and unstructured interview approaches (Cachia & Millward, 2011). Semi-structured interviews, as do the structured interviews, have a fixed set of sequential questions, but no prescribed answers. The questions serve as an interview guide allowing for additional questions to be introduced to facilitate further exploration of issues that might emerge during the interview process. This technique allows the researcher and respondent time and scope to explore issues in more depth for better understanding. Though this method may be time consuming it allows a researcher to collect data that is rich, that equips them with an in-depth understanding of interviewees’ opinions and responses which is conducive to analysis using qualitative techniques (Cachia and Millward, 2011; Blumberg, B., Cooper, D.R. and Schindler, P.S., 2008).

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 13 respondents out of a possible fifteen experts/respondents that were sought from OEMs and first and second tier suppliers within the Eastern Cape and the Gauteng Province and Automotive Associations.

The analysis and testing for validity and reliability of data collected was done through descriptive inference and statistical descriptive correlation analysis.

8

Finally an interpretation of the outcome of the study, recommendations and conclusion were given.

1.6.2 Research methodology

The qualitative research method or approach, which was used for this study, is also known as phenomenological or subjectivist or humanistic or interpretivist or new mind-set. The nature of qualitative research is inductive and subjective whereby theories are developed as outcomes. This method of research is used to identify patterns, ideas, describe phenomena as they are and obtain information on the characteristics of an issue or problem. After this the analysis allows the researcher to understand, explain phenomena and be able to apply the findings to solve problems (Blumberg et al., 2008).

1.6.3 Chosen qualitative methodology paradigm

A research paradigm is a set of beliefs or worldview of the researcher that guides action and is informed by an understanding of what and why research is undertaken. The need for research arises when an idea is to be explored or an issue is to be probed or a problem is to be solved (Clarke, 2005).The question of this study was to investigate whether or not organisations invested in capital as a result of the introduction of the Automotive Production and Development Programme (APDP). It is aimed to establish whether or not the APDP will succeed as a strategy for sustaining domestic production and reducing unemployment by evaluating business strategy shifts within the automotive industry. The intention was to assess capital investment by companies in response and preparation for APDP.

This question requires an understanding of business strategies and their link to the economy. The purpose of this study is thus exploratory and the suitable paradigm of the research study is going to be qualitative.(Arnolds, 2011)

9

1.7 SAMPLE

The purpose of sampling is to be able to select a subgroup out of a large group or population as a basis for making inferences about a larger group (Huysamen, 1994). Even though the automotive industry is global in nature, this study was due to constraints of accessibility, directed only at South African respondents. Also the APDP is SA legislation. Interviews were held with thirteen experts from three OEMs, first and second tier suppliers in the Eastern Cape and Gauteng Province, as well as representatives of two Automotive Associations.

The confidentiality and anonymity of respondents were guaranteed in line with the policy of ethics of the Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University Business School and this commitment was declared to the respondents in the form of a covering letter which accompanied the interview questions. This letter also served to inform the respondent of the purpose of the interview, that is, the fact that it the interview was be a data collection tool for an academic research study.

1.8 MEASURING INSTRUMENT

To collect data a questionnaire was developed based on the literature review and semi-structured interviews were conducted, with a recorder to capture the data. The questions asked were to gauge the level of understanding of the MIDP and APDP by industry participants. Additional questions in line with organisational investment in capital in response to the aforementioned government incentive and policy were also posed.

The semi-structured interviews were conducted with thirteen respondents out of a possible fifteen experts/respondents that were sought from OEMs, first and second tier suppliers within the Eastern Cape and the Gauteng Province and Automotive Associations.

10

The analysis and testing for validity and reliability of data collected was done through inference and descriptive analysis.

The collected data were captured on a common information repository and analysed by establishing commonality amongst the views and opinions in responses given by respondents in line with questions gauging the various themes.

Finally an interpretation of the outcome of the study, recommendations and conclusion were given.

1.9 DELIMITATIONS

Even though the automotive industry is global in nature, this study was due to constraints of accessibility, directed only at South African respondents. Also the APDP is SA legislation. Interviews were held with thirteen experts from three OEMs, first and second tier suppliers in the Eastern Cape and Gauteng Province, as well as representatives of two Automotive Associations.

1.10 TERMINOLOGY

The following terminology is frequently used in this study:

APDP: Automotive Production and Development Programme a successor to the MIDP (2013 – 2020), aiming to achieve local production of 1.2 million vehicles by 2020.

Automotive Industry: In this document, industry means vehicle manufacturing companies and institutions

LCP: Local Content Programme was the South African automotive policy between the years 1961 – 1995.

Investment in processes: the adoption of world class manufacturing practices and methods by individual organisations.

Investment in capital: investment in new facilities and technologies by individual organisations.

11

Investment in people: the training and skills development of individuals within an organisation.

NGP: New Growth Path – a policy launched by government (the Ministry of Economic Development) in November 2010, with aims to establish a more labour-absorbing economic growth path.

MIDP: Motor Industry Development Programme an initiative by government to enhance the global competitiveness of the automotive industry by supporting exports (1995 – 2012).

Stakeholders: Government, Automobile Manufacturers Employer’s Organisation (AMEO) and the National Union of Metal Workers of South Africa (NUMSA)

Supply chain management: planning, implementing and controlling of physical flow of materials and finished products from a point of origin to point of use.

First tier supplier: a company that produces components or systems assembled from components and sub-components normally supplied by lower tier suppliers and supply them directly to OEMs even across international borders.

Second tier supplier: lower tier supplier that is restricted to domestic manufacturing and supply of components.

Automotive association: a stakeholder within the automotive industry.

OEM – Original Equipment Manufacturers are vehicle assembling plants or factories. OES – Original Equipment Suppliers are component suppliers supplying vehicle manufacturers with components for manufacturing and assembling.

CBU – Completely Built-up Unit – a vehicle

NAAMSA – National Association of Automobile Manufacturers of South Africa

NAACAM - National Association of Automotive Components and Allied Manufacturers VWSA – Volkswagen Group South Africa

MBSA – Mercedes- Benz South Africa GMSA – General Motors South Africa Rehau – Rehau Polymer South Africa

12

1.11 OUTLINE OF THE STUDY

Chapter one outlines the scope of the study through discussions of the reason for the research and its importance.

Chapter two covers the literature review on strategies within the automotive industry between the years 1995 up to the point in 2008 when the successor of the MIDP was announced and subsequent strategy changes thereafter.

Chapter three covers the research design and methodology which focuses on sampling, data collection, instruments of analysis and interpretations.

Chapter four discusses the research findings and present level at which individual SA companies are geared for APDP.

Chapter five covers a summary of key research findings and reflects on recommendations.

1.12 SUMMARY

An explanation of why the automotive industry is critical to the economy of South Africa and requires government support has been indicated in this chapter. This chapter also outlined the background and the importance of this study pertaining to the South African government and the automotive industry as a whole.

A problem statement which motivated the study, the primary research question to be answered, the design and research methodology, the sampling, data collection technique and measuring instrument to be used were discussed.

Since South Africa is currently in the process of phasing out the MIDP and introducing the APDP by 2013, organisations within the automotive industry need to align with the new policy. Non-alignment could lead to non-compliance and a failure to benefit from

13

the incentives as well as create reputational problems for the organisation. Therefore, this study investigated how an organisation can review its manufacturing process strategies with regard to its capital investment in equipment to align with the policy, so that significant benefits from the new policy are realised. The research question was:

“Have the companies within the automotive industry in South Africa geared up their manufacturing processes, with specific reference to capital investment, in preparation for the APDP?”

Lastly the terminology that has been used in the study was defined and the outline of the study was declared.

14

CHAPTER 2 LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1 INTRODUCTION

The research question of this study was: “Have the companies within the automotive industry in South Africa geared up their manufacturing processes, with specific reference to capital investment, in preparation for the APDP?”

If it were not for globalisation and more specifically foreign direct investment, South Africa (SA) would be lagging international manufacturers by significant margins. This is a view shared by Lorentzen and Barnes (2004) who argue that in order for developing countries such as SA to progress technologically and innovatively, foreign capital and local capability play an important role or at least the compatibility thereof, in that when local and foreign factors complement one another, technology transfer and diffusion, where diffusion refers to the adaptation and modifications done to acquired foreign technology, are easily facilitated and the fruits thereof seen through the level of development in that country.(Lorentzen and Barnes, 2004)

Because of extensive liberisation of trade and investment systems, as a result of policy reforms that took place in the 1980s and 1990sin developing countries, local firms encounter competition from foreign firms and products more readily (Damoense and Simon, 2004). Thus, aggressive growth in the interaction between local technology and imported knowledge became rife, often in the form of foreign direct investments (FDI), interactions in which the results depends heavily on the capabilities of the local firm and host country both at micro and macro level. Capabilities at micro level include the level of desire for new knowledge, skill level and diffusion of internal knowledge within relevant manufacturers. At macro level investment in education, information systems and infrastructure development within host country are key influential factors to successful interaction between local and foreign technology (Lorentzen and Barnes, 2004).

15

In developing countries, success of the automotive industry is taken as an indication of economic growth, a sign of modern and foreign technology mastery. Hence governments deem it as vital to establish strong government policies supporting and promoting the automotive sector. A classic case of where this has worked well is in South Africa (SA) a country that, as a result of state-led intervention, has recorded growth in exports of vehicles and components, as well as FDIs undertaken in the last decade. However this is not a situation peculiar to SA as the automotive sector has attracted much attention across the globe, especially as far as developing economies are concerned (Flatter, 2002).

2.2 CHANGES TO GOVERNMENT LEGISLATION

Government and regulatory agencies play a vital role in ensuring promoting the attractiveness of individual countries to foreign investors. Governments, having realised that FDI offers employment opportunities over and above what domestic investment and resources do, focused on developing investor friendly policies to encourage FDI, which in this context being an acquisition of controlling interest in foreign companies or construction of factories, structures and equipment on foreign soil by an organisation from one country to another (Shendge, 2012).

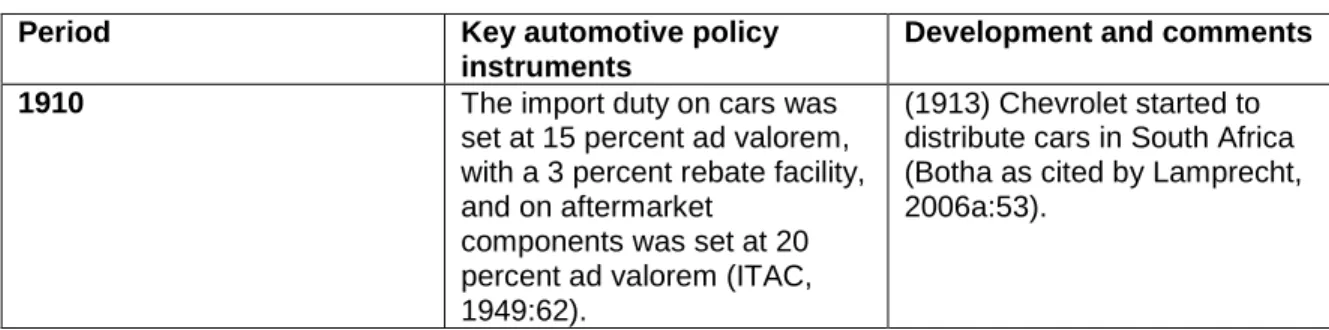

Table 1 below gives a summary of the changes to government legislation and policy in SA between 1910 and 1995:

Table 1: A summary of the changes to government legislation in SA (1910 – 1995)

Period Key automotive policy

instruments

Development and comments

1910 The import duty on cars was

set at 15 percent ad valorem, with a 3 percent rebate facility, and on aftermarket

components was set at 20 percent ad valorem (ITAC, 1949:62).

(1913) Chevrolet started to distribute cars in South Africa (Botha as cited by Lamprecht, 2006a:53).

16

1915 An increase of the import duty on cars to 20 percent ad valorem, with a 3 percent rebate facility (ibid, 1949:62). 1924 An increase in the import duty

on passenger cars to 20 percent, 22 percent and 25 percent ad valorem. The higher duties applied to the higher valued cars. The 3 percent rebate facility was withdrawn on British cars (ibid, 1949:62).

An increase in the import duty on assembled or unassembled trucks from 3 percent ad valorem to 20 percent ad valorem and on chassis for these vehicles, assembled or unassembled, to 5 percent ad valorem (ibid, 1949:69).

(1924) Establishment of Ford Motor Company of South Africa. The coastal location allowed for the easy importation of components (ITAC, 1949:5). Model T assembly comprised 13 000 units in 1924 (Swart, 1974:164).

1926 A reduction of the import duty on chassis for bodies from 20 to 10 percent ad valorem in order to promote domestic body manufacturing (ibid, 1949:63).

The first reference to used cars in the tariff. The import duties on used cars were set at similar rates to those for new cars (ibid, 1949:66). A reduction of the import duty on parts and materials for chassis and bodies for cars to 15 percent ad valorem, subject to certain conditions (ibid, 1949:64).

(1926) Establishment of General Motors South African Limited (ITAC, 1949:5).

1929 A reduction of the import duty on assembled or unassembled chassis on trucks from 5 to 3 percent ad valorem (ibid, 1949:67).

(1929) The South African Bureau for Labour Statistics indicated that the automotive industry showed the greatest instability of employment of all the industries. The changing of models annually, which caused certain plants to close down for a month, the

perception of automotive assembly as low and semi-skilled, as well as low unemployment rates at the time were reasons mentioned for this phenomenon (ibid, 1949:35).

17

1931 Provision made for the first rebate facility for the importation of certain parts and materials for the assembly of cars as well as bodies for cars (ibid, 1949:73, 74). 1932 An increase in the import duty

on cars by an additional 5 percent (ITAC, 1932a:3). The imposition of an exchange dumping duty on cars from the UK and Canada (ibid, 1932b:2).

1934 Various rates of protective duties on identifiable automotive components recommended and implemented based on industry petitions (ITAC, 1949:71–73).

Provision was made for unassembled chassis for cars, set at 10 percent ad valorem, and for bodies, parts and materials, set at 12,5 percent ad valorem (ibid, 1949:65).

(1933) Vehicle assembly by Ford and General Motors increased to 33 000 units per annum (Swart, 1974:164). (1934) Long-term automotive policy was still to encourage domestic manufacturing of automotive components as well as for the import duty difference between assembled and unassembled cars not to be too big (ITAC, 1960:29, 83).

1939 The ad valorem import duties

on cars, chassis and body parts were switched to specific duties at rates equal to the ad valorem duty rates (ibid, 1949:62).

(1939) Establishment of National Motor Assemblers Ltd in Johannesburg. The

company assembled various vehicles on contract for several overseas OEMs. Components such as glass and tyres were being

manufactured both as original equipment and for the

replacement market (Swart, 1974:164). The average South African vehicle age was 5,5 years (ITAC, 1949:13).

1947 The specific import duties

were switched back to ad valorem duties as well as increased to 25 percent and 30 percent ad valorem on cars. The higher duties applied to the higher valued cars (ibid, 1949:63).

(1943 to 1945) Imports and assembly of cars came to a standstill owing to World War II (ITAC, 1960:15).

(1947) Five assembly plants were operational in South Africa with a capacity design of 83 000 units. All plants focused on US brands, except for General Motors, which also

18

assembled the British Vauxhall (ITAC, 1949:6, 7).

(1947) South Africa was ranked seventh out of 141 countries in terms of global vehicle use with a ratio of 26 persons per one car (ibid, 1949:5).

(1948) The first installation of moving production lines took place at General Motors and Ford (ibid, 1949:38).

(1948) A high rate of imports led to problems with the balance of payments. Import control was instituted through the granting of monetary quotas. This limited the number of imported vehicles and CKD kits (Swart, 1974:164)

1956 An excise duty was introduced

on cars based on vehicle mass (ITAC, 1960:59).

(1950–1957) Passenger vehicle sales averaged 36 000 units per annum. When the import quotas were eliminated sales increased to 100 000 units in 1957 (Swart, 1974:164).

(1958) South Africa was ranked ninth in the world’s passenger car parc (number of registered vehicles), above other vehicle-producing countries such as Brazil, India, Japan and various European countries (ITAC, 1960:9). (1958) Eight OEMs operated in South Africa, of which five were foreign owned and assembled 75 percent of total vehicles assembled. Three OEMs assembled vehicles on contract on behalf of other companies. Seven of these firms were situated at the coast with the component manufacturers in close proximity. The increase in the local content of vehicles, from single digit levels to 18 percent, was regarded as a significant process of evolution (ibid, 1960:15, 22).

19

1959 Recommendations were made

to develop the automotive industry in South Africa. These recommendations included an increase in the duty on passenger cars and light commercial vehicles; to levy an excise duty on domestically assembled vehicles and completely knocked down (CKD) kits; to provide additional protection to domestic component

manufacturers; and to create rebate provisions subject to local content requirements (ibid, 1960:85).

1961–1963 Phase I of the local content programme was introduced with the objective to increase local content in mass from 15 to 40 percent (ITAC, 1988:4). The ad valorem duty on imported motor cars was set at 35 percent plus an additional percentage up to a maximum of 100 percent, depending on the value and the weight of the car. The level of excise

rebates on motor cars varied between 15 percent (for a local content of between 25 percent and 30 percent by weight) and 75 percent (for a local content of more than 70 percent). Components generally attracted a duty of 20 percent ad valorem (ITAC, 1965:2).

(1960) South Africa produced 120 000 vehicles, more than any other developing country in the world. The local content level was only 20 percent (Black, 2007:73).

(1963) The main competition for the domestic vehicles did not stem from imported cars but from other domestically assembled vehicles with a lower local content. The position vis-à-vis a competitor was broadly determined by the degree to which the cost premium attached to the higher priced domestically sourced components were offset by the additional excise rebates for the higher local content (ITAC, 1965:2). 1964–1969 Phase II of the local content

programme was introduced to increase the nominal local content in mass from 45 percent in 1964 to 55 percent 1969. This was equivalent to a 50 percent net local content, as redefined. The

determination of the net local content was complicated and required government approval for certain parts,

sub-assemblies or materials, as local content (ITAC, 1988:4; ITAC, 1965:22).

(1964) Record new vehicle sales of 143 373 units was achieved in the domestic market (ibid, 1965:7).

20

1971–1976 Phase III of the local content programme was introduced, with a minimum net local content of 52 percent at the beginning of 1971, to increase to 66 percent on 1 January 1977 (ITAC, 1988:4).

(1975) The 13 OEMs operating plants in South Africa assembled 39 models and were supplied by 300 automotive component manufacturers. The GDP contribution of the automotive sector was 3,3 percent (ITAC, 1977:8, 70).

1977–1978 Phase IV of the local content programme comprised a two-year “standstill” phase. This was to assist industry in consolidating its position after the severe narrowing of profit margins during the previous three years (ibid, 1988:4).

(1979) Disinvestments by General Motors and Ford occurred owing to the

sanctions against South Africa (Gelb, 2004:41–45).

(1976–1986). The number of OEMs decreased from 16 to seven and the number of models produced from 53 to 20. This was owing to recessionary conditions, the significant devaluation of the rand in 1984 and 1985 and escalating domestic inflation. All seven OEMs recorded losses in 1985 (ITAC, 1988:26, 63, 64). 1980–1988 Phase V of the local content

programme was introduced with a minimum net local content of 66 percent by mass, in respect of motorcars, and 50 percent by mass, in respect of light goods vehicles and minibuses (ibid, 1988:7).

(1980–1984) Locally manufactured engines, gearboxes and axles for commercial vehicles were introduced. ADE and ASTAS were accorded the rights to be the sole manufacturers for the engines and gearboxes, respectively, for commercial vehicles. The ADE engine had a price disadvantage of 100 percent against the free on board value of an imported engine. A total of 19 commercial vehicle

assemblers operated in the domestic market (ITAC, 1985:8, 10).

1989–1995 Phase VI of the local content programme was introduced and involved a radical change in the calculation of local content based on value as opposed to mass. Phase VI encouraged local OEMs to increase local content from an industry average estimated at 55 percent at the inception of the programme to 75 percent (including exports) by the year

(1989) A budgetary constraint was placed on Phase VI in that the programme had to be self-funded. Thus the ordinary excise duty and excise duty rebate had to be equal (ITAC, 1992:2).

(1991–1994) Samcor exported vehicles from South Africa in 1991, Volkswagen in 1992 and BMW in 1994 (Damoense and Alan, 2004:264).

21

1997. Phase VI sought to reduce the foreign exchange used by the vehicle

manufacturing industry by about 50 percent over the period 1989 to 1997. Local content was defined as the ex-works price less foreign currency used, including profit and overheads. This meant that pricing could be used to create local content. The import duty on aftermarket parts and components for motor vehicles was increased to 50 percent ad valorem and on passenger cars to 100 percent ad valorem, whether or not assembled. Exports were allowed and accounted to be part of the local content value. An excise duty of 40 percent on the value of locally assembled vehicles applied, of which up to 37,5 percent was rebated based on the local content level (ITAC, 1989:26– 33). The effective rate of protection for the industry was calculated to be in excess of 400 percent (MITG, 1994:31).

(1992) Price comparisons of passenger cars between South Africa and Germany, Japan, the USA, the UK and Australia reflected a South African price disadvantage of up to 72 percent. The lowest-priced car category prices were competitive but in the higher-priced categories the price inelasticity enabled OEMs to achieve higher margins (IDC, 1993:15–17). (1993) The seven OEMs produced 39 different passenger car and light commercial vehicle models (MITG, 1994:35).

In 1994 there was a reduction of the import duty on

passenger cars to 80 percent ad valorem from 1 January 1994 (ITAC, 1994:1).

In 1995 there was a reduction of the import duty to 75 percent ad valorem on passenger cars from 1

January 1995. The payment of a 15 percent surcharge on passenger cars and 5 percent on commercial vehicles was exempted (ibid, 1994:1). Implementation of the MIDP.

Source: Lamprecht (2009: 208-212)

Before 1960, as can be seen in Table 1above, the South African automotive industry was characterised by high levels of protectionism, where there were import substitution policies. The policies that were in place then called for high tariffs on imports and vehicles produced were mainly for the local market. These policies resulted in the

22

industry having many small-scale firms that carried high costs of production, due to the number of different models and makes some of the firms produced. Though the elimination of competition was somewhat profitable to the local manufacturers, the high degree of local competitors had its pressures. In response to rivalry, manufacturers introduced new models, an activity which, due to the relatively small size of the local market, proved costly and thus negated profits earned.

As was common among economies with import substitution policies, South Africa began to experience reduced circulation of foreign exchange and trade deficits. By 1960, prompted by a need to reduce trade deficits that came as a result of vehicles that were predominantly produced locally from imported components, a revision of trade policies was imminent. 1961 saw new policy regime emergence, a policy that introduced a range of local content programmes (LCP) that imposed a requirement for higher local content on the vehicles produced domestically, as opposed to the 20 percent of local content that the vehicles contained in years prior.

1971 saw the end of the second phase of the local content programme which gave rise to a third phase that demanded that products of manufacturers have at least 52 percent local content as measured by the weight of the local components. Even though this policy supported development of local component manufacturing, because of the low scale of production by the manufacturers of vehicles, the operating costs proved high. The demand for local content grew from 52 percent to 66 percent by 1977. The local programmes received reviews until the fifth phase, and then 1989 saw the end of the fifth phase of the programme and birth of the sixth phase (Phase VI).

Phase VI (1989 – 1995) was a policy which sought to abandon import substitution and steer the industry towards exports to be able to improve foreign exchange difficulties. The assumption that was made was that as much as limiting imports caused the problem of reduced foreign currency, exporting would reverse the effect. As per Phase VI the export of vehicles or components constituted local content and manufacturers could reduce the amount of locally produced components used on assembly of their vehicles as local components proved more expensive than imported components.

23

An additional step to incentivise the manufacturer of vehicles or completely built-up (CBU) units to produce more and the component manufacturer to export more, the demand for local content in the manufacturing of vehicles was reduced from 66 percent to 50 percent.

Even though the export of components grew as a result of the policy changes under the Phase VI regime, the export of CBUs remained minimal due to low scales of production and the higher costs associated with such conditions. With manufacturers opting to meet the 50 percent local content requirement rather than pay duties on imported components, this meant that the components industry did not suffer much, but instead had an opportunity to export more of their products and earn more credits. This meant that Phase VI had met its objective of rationalising production in the component sector, but not as far as the vehicle manufacturers were concerned.

So when one of the objectives of Phase VI, which was to rationalise production in the automotive industry, failed as a result of an emergence of an increase to new domestic models rather than the expected higher volumes. A consequence of this failure was a review of Phase VI and the introduction of the MIDP in 1995, a policy which sought to (Black and Shannon, 2002 and Barnes and Morris, 2000):

a) Reduce tariffs on light vehicles and components, with tariffs being phased down even faster than prescribed by the World Trade Organisation (WTO), with a tariff phase down schedule that reduced rates of protection of over 100 percent under phase VI to 40 percent for CBU and 30 percent for CKD by 2002;

b) Abolish local content requirements/ regulations;

c) Introduce a duty- free allowance of up to 27 percent of the wholesale value of the vehicles manufacturers produce;

d) Introduce duty rebate credits to be earned on exports of vehicles and components for redeeming when importing vehicles and/ or components, an import-export complementation (IEC) scheme; and

e) Offer a small vehicle incentive (SVI) in the form of a subsidy for the manufacturer of affordable CBUs functioning via a drawback mechanism of duties to the value contingent upon the ex-factory value of the CBU.

24

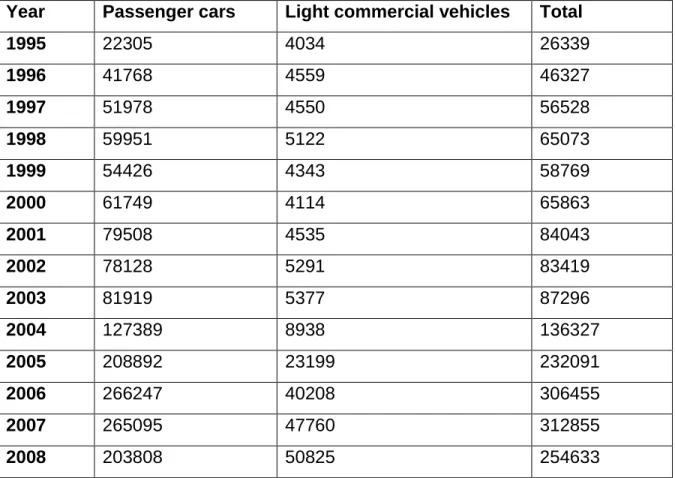

The MIDP was seen as an appropriate response to the challenges and threats which were presented to the South African automotive industry by the regime of the inward oriented LCPs. An outward oriented policy, that would support global integration of the South African industry into international value streams, was deemed necessary by government. The introduction of the MIDP resulted in a dramatic surge of exported and imported vehicles as shown in Table 2 below. This surge was made possible by duty rebate credits earned from the increased exporting of vehicles and components which continued to grow further, even under the new policy, as a result of increased investment in capital. Table 3 below gives an indication of how domestic production grew since year 1995 to 2008 (Black and Shannon, 2002).

Table 2: Import of vehicles between 1995 and 2008

Year Passenger cars Light commercial vehicles Total

1995 22305 4034 26339 1996 41768 4559 46327 1997 51978 4550 56528 1998 59951 5122 65073 1999 54426 4343 58769 2000 61749 4114 65863 2001 79508 4535 84043 2002 78128 5291 83419 2003 81919 5377 87296 2004 127389 8938 136327 2005 208892 23199 232091 2006 266247 40208 306455 2007 265095 47760 312855 2008 203808 50825 254633 Source: Lamprecht (2009: 257)

25

Table 3: Vehicles produced in South Africa (units) between 1995 and 2008

26

Part of the South African government’s success was to ensure at introduction in 1995, that the MIDP was compliant with the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) and the WTO regulations established in Uruguay in 1994. The MIDP itself, as did the LCPs, underwent reviews on numerous occasions to ensure that it remained relevant to the economic conditions of given times. The first phase of the MIDP ran from September 1995 to June 2000 and the second phase from July 2000 till 2007, with the third phase set to run from the end of the second phase till 2012. The reviews which took place served to propose amendments to policy in an attempt to meet challenges of globalisation and rapid technological changes.

The possibility of measuring progress of the MIDP is difficult, but feasible through an evaluation of macro-economic conditions or indicators based on the objectives of the MIDP which included (Damoense and Simon, 2004 and Barnes and Morris, 2000):

a) Developing a globally integrated and competitive SA automotive industry. For this competitiveness indicators depicted on competitiveness reports issued by various research bodies give clear indication that since the introduction of the MIDP the South African automotive industry has enjoyed competitiveness improvements.

b) Stability in long – term employment levels in the industry. Reports by the Department of Trade and Industry (the DTI) indicate that on introduction of the MIDP employment levels in the automotive industry increase, but have in later years declined.

c) Improving the affordability and quality of vehicles. Reports issued by the National Association of Automobile Manufacturers of South Africa indicated a fall of over 12 percent in prices of new vehicles since 1995.

d) Further promoting the expansion of automotive exports and improving the sector’s trade balance. Even though with the introduction of the MIDP the

27

exports grew the imports still exceed the exports by far, which make South Africa a net importer resulting in a negative trade balance.

e) Contributing to the country’s economic activity. The best way to measure this indicator would have been to consider value added, but because of such data being unavailable, the gross domestic growth figures suffice as an indication of growth, and since the introduction of the MIDP the DTI reported a positive trend to the domestic automotive industry. In 1996 R28.7 billion was reported, followed by R 31.2 billion in 1997, results indicative of successes of the MIDP.

Black (2001) states that, based on a survey conducted on component manufacturers or suppliers, it showed that companies were aware of the changes the introduction of the MIDP in 1995 would introduce and that they were clear on how to respond to the new programme. Companies expected an increase in exports, a moderate increase in investment and stable employment hence the successes of the MIDP (Black, 2001).

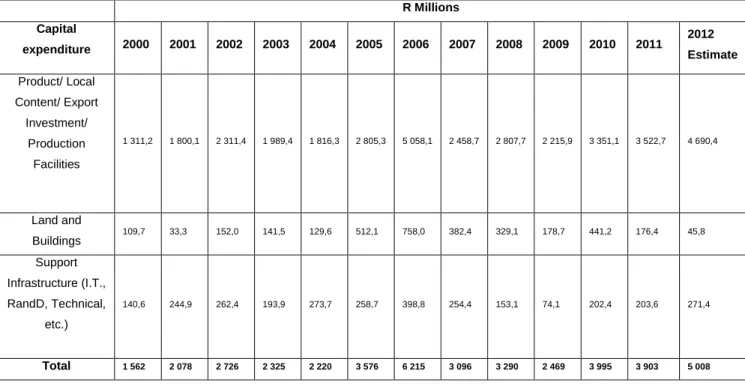

Although there were notable detractors of the MIDP, it certainly proved to be a successful state initiated incentive programme. The programme attracted massive local and foreign investments, as shown in Table 4 below, rationalising the number of locally produced vehicles, vastly improving production capacity utilisation and improving overall operational efficiencies. According to NAAMSA (2011), between the introduction of the MIDP in 1995 and 2005, aggregate production of vehicles rose by 34 percent and light commercial vehicles (LCV) by 29 percent. When compared to the start of 1995, the export of vehicles and LCVs at the end year 2005 improved 13 fold and 402 percent respectively.

The MIDP also achieved successes cutting the complexities in manufacturing plant areas where the LCPs had failed (Black, 2002). The number of base model cars or production lines and LCVs produced domestically had reduced from 42 produced in 1995 to 22 by 2006, such thatit proved an effective manner of improving efficiencies. The average annual volumes of produced vehicles per modelwent up from 8 515 to 22 609 over this period, with high volume production models going from 0 to 5 from 1995 to

28

2005. High volume production models are specific models that get produced in excess of 40 000 units a year (NAAMSA, 2011).

Local manufacturers have had to drastically change the way they conduct their business to capital investments concentrated on new high volume products, more local content, export orientated investment and improved production facilities. Highly automated modern automotive manufacturing factories emerged as a response to the rising and required high volumes of production. Pressures brought on the domestic automotive industry by globalisation led to a focus on reducing costs of producing, improving quality and the reliability of supply and being far from the export markets only meant added costs due to transport and logistics related activities (Damoense & Simon, 2004).

Even though employment levels would not have been expected to change under automation activity, the number of total employees in the automotive industry in South Africa increased from 280 870 in 1999 to 306 300 by the end on 2004. This significant growth is indicative of a healthy and developing automotive industry. The increased competition in the automotive industry as a result of globilisation hashad a positive spin-off on the consumer with prices of vehicles remaining virtually stable and below inflation. That occurence is a direct result of import duties on components and CBUs being drastically decrease, providing consumers with a wide choice of products at competetively affordable prices (Barnes and Morris, 2008).

The investment discussed above, in the automotive industry in SA over the last decade is shown in Table 4 below:

29

Table 4: Capital Expenditure on an Annual Basis

R Millions Capital expenditure 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 Estimate Product/ Local Content/ Export Investment/ Production Facilities 1 311,2 1 800,1 2 311,4 1 989,4 1 816,3 2 805,3 5 058,1 2 458,7 2 807,7 2 215,9 3 351,1 3 522,7 4 690,4 Land and Buildings 109,7 33,3 152,0 141,5 129,6 512,1 758,0 382,4 329,1 178,7 441,2 176,4 45,8 Support Infrastructure (I.T., RandD, Technical, etc.) 140,6 244,9 262,4 193,9 273,7 258,7 398,8 254,4 153,1 74,1 202,4 203,6 271,4 Total 1 562 2 078 2 726 2 325 2 220 3 576 6 215 3 096 3 290 2 469 3 995 3 903 5 008 Source: (NAAMSA, 2011)

Similar to the LCP policies, the MIDP did not perform without reviews for improvement and adaptation. In 2008 after the third review, of all the reviews that took place in1999 and 2002, a successor to MIDP, the Automotive Production and Development Programme (APDP) was named. The reform came as a result of an industry review that revealed, despite its successes, South Africa and the sub-region remained a relatively small market in global terms, contributing less than 1 percent of the global production and remained isolated from larger markets and shipping routes. The reviews also highlighted challenges of major domestic infrastructure and logistical inefficiencies, together with severe skills shortage, among other things.

In response to an announcement by the DTI of this successor to the MIDP, NAAMSA, through Dr Johan Van Zyl the then President of that body, commended this revelation, stating that a finalisation of a future automotive industry policy framework served to strengthen the country’s international trade commitments. The framework covered import duties, a local assembly allowance, a production incentive and an investment

30

allowance which provided the industry with a solid base to rise to the challenges presented by international competition and demands to produce new cars and light commercial vehicles in South Africa. The local assembly allowance supports continued production of vehicles in South Africa, the investment allowance an incentive to stimulate domestic vehicle production and additional localisation (NAAMSA, 2011).

As mentioned in section 1.3 above, the APDP serves as an affirmation of the commitment made by government through the New Growth Path (NGP) policy, to make employment creation the main criterion for economic policy. The automotive industry has been identified as one of the job drivers in the economy and therefore its policies are designed to ensure the economy becomes both competitive and more employment friendly. The APDP aims to stimulate growth in the automotive vehicle production industry from 600 000 to 1.2-million vehicles per annum by 2020 with associated deepening of the components industry. The new programme will focus on value addition while being consistent with South Africa's existing multilateral obligations (The DTI, 2010).

The NGP policy, launched in November 2010 by the Ministry of Economic Development, in its objectives aims to create 5 million new jobs by 2020, reducing unemployment from 25 percent to 15 percent. This it aims to achieve through ensuring that economic policies are designed to enhance economic competitiveness and a more employment friendly climate (The DTI, 2010). Lamprecht (2009) supports this notion, adding that the MIDP promoted sustainable employment opportunities within the automotive industry, and that this industry has a multiplier effect, in that for every job in the manufacture of a vehicle there are two or more jobs created in the rest of the value chain ( component manufacturing, vehicle sales, service, repairs, and so on). The changes in employment in the automotive industry over the period of the MIDP from 1995 to 2008 are shown in Table 5 below:

31

Table 5: South African automotive industry employment levels (number of employees), period year 1995 – 2008

Source: Lamprecht (2009)

The MIDP objectives of improving global competitiveness, enhancing growth through exports, vehicle affordability, improving industry’s skewed trade balance and stabilising employment, were achieved through a series of export-oriented incentives coupled with tariff reductions. The key elements of these export incentives being (Barnes, J., Kaplinsky, R. and Morris, M., 2003);

a) The abolition of a minimum content provision and the introduction of an import export complementation (IEC) scheme, which allowed both OEMs and component manufacturers to earn duty credits from exports:

b) A tariff phase down schedule designed to reduce the nominal rates of protection to 38 percent for completely built-up units (CBU) and 29 percent for completely knocked down (CKD) components by 2003:

32

c) A duty free allowance for assemblers of 27 percent of the wholesale value of the vehicle:

d) A small vehicle incentive (SVI) providing for a subsidy for the manufacturer of more affordable vehicles, and

e) A Productive Asset Allowance (PAA) providing duty equivalent to 20 percent of investments spread over a period of 5 years, but this was applied to investments designed for exports enhancing scales of a particular product line.

The new APDP is also structured into four key elements; namely, tariffs, local assembly allowance, production incentives and automotive investment allowance:

a) The tariffs from the MIDP to the APDP will remain unchanged for the full intended term of this policy, which is up until 2020.

b) The local assembly allowance (LAA) will allow vehicle manufacturers, with a plant volume of at least 50 000 units per annum, to import a percentage of their components duty-free. An allowance realised in the form of duty credits issued to vehicle assemblers based on 18 percent to 20 percent of the value of light motor vehicles produced domestically from 2013.

Manufacturers stand to also to receive value-add support to help encourage increased levels of local value addition along the automotive value chain, with positive spin-offs for employment creation (Makapela, 2010). Indicated below in Table 6 is a brief outline of the differences between the MIDP and APDP.

33

Table 6: A quick comparison between the MIDP and APDP

Source: Barnes (2011)

Amid optimism regarding the APDP, there are concerns and worries about the APDP regarding the lower export incentives it brings for components producers. According to Werbeloff(2011) NAACAM’s Steward Jennings expresses concern about the uncertainty of the APDP which has cost the components industry contracts stating that original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) or vehicle manufacturers use more multinational suppliers, whom in turn, predominantly use imported sub-components in their assembly processes. This is an undertaking which he claims destroys local sub- supplier capabilities and the cost competitiveness of the local component manufacturer as a whole. However, Jennings indicated some of the reasons why the local components industry was under threat under the APDP as follows:

a) Global decision making pertaining to prices on vehicle and component production; b) Increases in electricity, wages, logistics and a strong and volatile rand;