The Geology of the Mono Craters, California

Full text

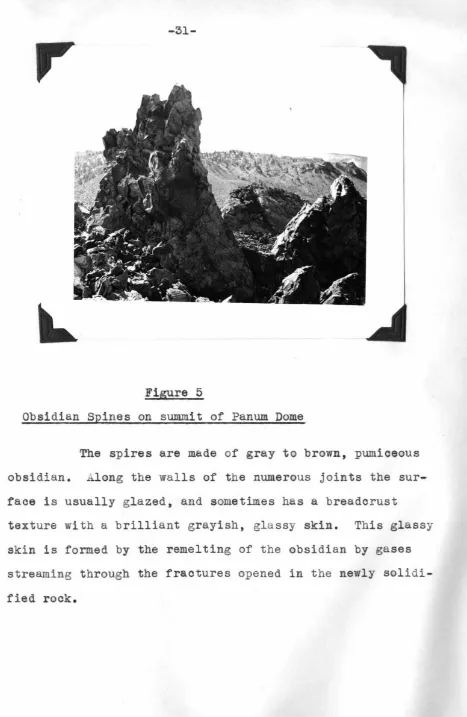

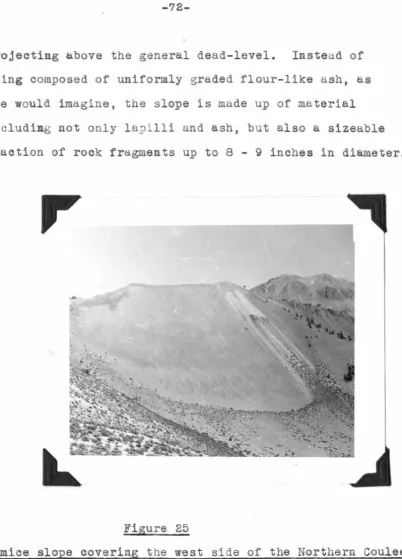

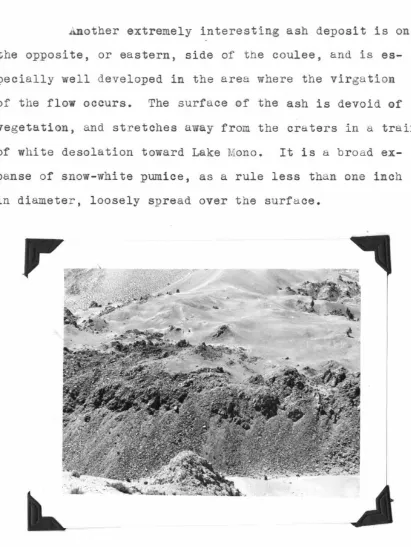

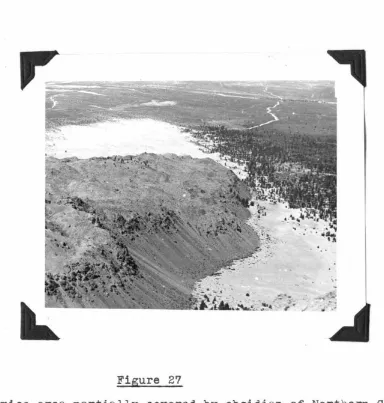

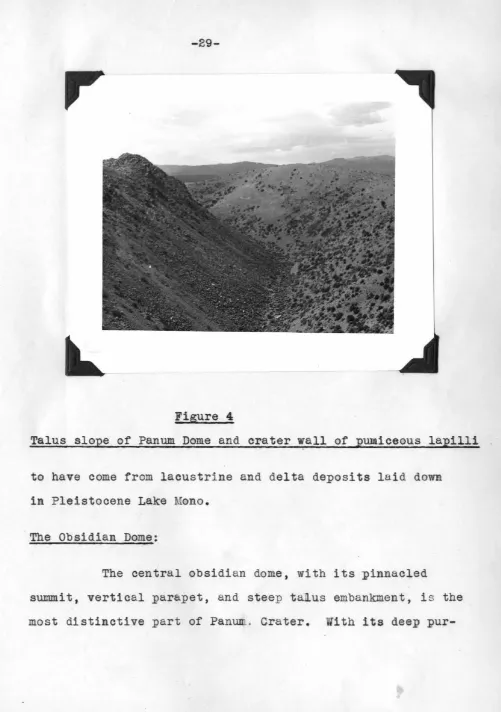

Figure

Related documents

Proprietary Schools are referred to as those classified nonpublic, which sell or offer for sale mostly post- secondary instruction which leads to an occupation..

4.1 The Select Committee is asked to consider the proposed development of the Customer Service Function, the recommended service delivery option and the investment required8. It

However, obtaining bacterial genomic information is not always trivial: the target bacteria may be difficult-to-culture or uncultured, and may be found within samples containing

Results suggest that the probability of under-educated employment is higher among low skilled recent migrants and that the over-education risk is higher among high skilled

Acknowledging the lack of empirical research on design rights, our paper wishes to investigate the risk of piracy and the perceptions of the registered and unregistered design

• Follow up with your employer each reporting period to ensure your hours are reported on a regular basis?. • Discuss your progress with

The corona radiata consists of one or more layers of follicular cells that surround the zona pellucida, the polar body, and the secondary oocyte.. The corona radiata is dispersed

○ If BP elevated, think primary aldosteronism, Cushing’s, renal artery stenosis, ○ If BP normal, think hypomagnesemia, severe hypoK, Bartter’s, NaHCO3,