MARTIN, SARAH ELIZABETH. Part-time Community College Faculty Perceptions of Assessment. (Under the direction of Dr. Susan Barcinas).

This instrumental case study explores how part-time faculty perceive and navigate assessment and the assessment environment within their community college. Part-time faculty comprise 67% community college faculty in an era of accountability, and their engagement with assessment should be understood. Cultural Historical Activity Theory (CHAT) is the theoretical framework for this study as it offers a systems perspective on the ways part-time faculty,

perceive and engage with assessment in their environment. CHAT is a learning theory and following these subjects through an assessment environment helps understand how they learn to engage with assessment at their institution. The research questions used to explore this

environment are: 1) how do part-time community college faculty perceive and describe the assessment environment within their community college? And 2) how do part-time faculty perceive and describe the nature of their engagement with assessment initiatives at their

a focus student learning outcomes assessment as well as how pay structures inform assessment. Finally, implications for practice in the community college are discussed in the areas of

by

Sarah Elizabeth Martin

A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty of North Carolina State University

in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of

Doctor of Philosophy

Educational Research and Policy Analysis

Raleigh, North Carolina 2019

APPROVED BY:

_______________________________ _______________________________ Dr. Susan Barcinas Dr. Diane Chapman

Committee Chair

DEDICATION

BIOGRAPHY

My career spans many areas – from the design and implementation of routed/switched networks to librarianship to leading a team of educators, process improvement educators, and instructional designers in healthcare. I have worked for non-profits, banks, technology firms, as well as in higher education. The common thread through these positions is a desire to teach, mentor, and learn from my colleagues – something I continue to do in all my endeavors.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

TABLE OF CONTENTS

CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION ... 1

Background and History ... 1

Statement of the Problem ... 3

Purpose and Guiding Research Questions ... 8

Research Methodology ... 9

Theoretical Framework ... 9

Significance of Study ... 11

Definition of Terms ... 15

Summary ... 15

CHAPTER 2: LITERATURE REVIEW ... 17

A Brief History ... 17

Community Colleges: Mission and Vision ... 19

Open access: Who attends Community College ... 21

Governance ... 25

Community College Pay and Tenure ... 27

Professional Development ... 30

Faculty ... 33

Part-time faculty ... 34

Assessment in Higher Education ... 36

History ... 37

Post-secondary education and Voluntary Systems of Accountability ... 38

Culture and Faculty ... 41

Neoliberalism and Accountability ... 42

Assessment Activities ... 43

Performance of Assessment in Post-secondary education ... 47

Socio Cultural Systems, Frameworks, and Theories ... 48

Culture and Assessment ... 48

Distributed Cognition ... 49

Communities of Practice ... 50

Actor-Network Theory ... 51

Cultural Historical Activity Theory ... 53

Theory and Theorists: History of CHAT ... 54

First Generation ... 54

Second Generation ... 55

Third generation ... 58

CHAT application to adult education ... 60

Discussion ... 62

CHAPTER THREE: METHODOLOGY ... 66

Qualitative Research ... 66

Case Study ... 67

Theoretical Framework ... 68

Data Gathering and Site Selection ... 70

Recruitment Process ... 71

Data source: Interviews ... 73

Subjectivity ... 76

Positionality ... 78

Rigor ... 79

Limitations and Strengths ... 80

Limitations ... 80

Strengths ... 80

Ethics and IRB ... 81

Conclusion ... 81

CHAPTER 4: RESEARCH FINDINGS ... 83

Introduction ... 83

Activity System ... 83

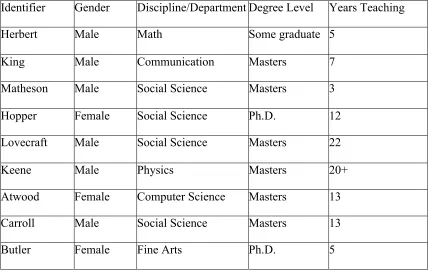

Participants ... 84

Herbert ... 85

King ... 89

Matheson ... 92

Hopper ... 96

Lovecraft ... 101

Keene ... 105

Atwood ... 109

Carroll ... 112

Butler ... 114

Dick ... 117

Study Findings ... 121

Thematic Findings ... 122

The Subject: Part-time Faculty ... 122

Tools and Instruments ... 125

Rules ... 130

Community ... 135

Division of Labor ... 139

The Object: Assessment ... 142

Summary ... 147

CHAPTER 5: CONCLUSIONS, IMPLICATIONS, AND RECOMMDATIONS ... 149

Research Questions ... 149

How do part-time community college faculty perceive and describe the assessment environment within their community college? ... 149

How do part-time community college faculty perceive and describe the nature of their engagement with assessment initiatives at their community college? ... 155

Discussion ... 161

Implications ... 168

Theory ... 168

Practice ... 170

Research ... 174

Closing Remarks ... 175

REFERENCES ... 176

APPENDICES ... 200

Appendix A ... 201

LIST OF TABLES

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure 1: Vygotsky’s first-generation action triangle ... 55

Figure 2: Second generation activity triangle ... 57

Figure 3: Third generation CHAT model ... 59

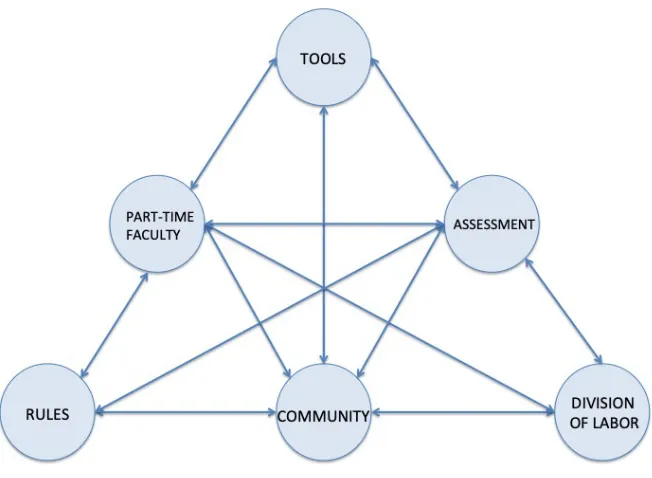

Figure 4: The CHAT Activity system ... 84

Figure 5: CHAT Subject ... 122

Figure 6: CHAT Tools ... 125

Figure 7: CHAT Rules ... 131

Figure 8: CHAT Community ... 136

Figure 9: CHAT Division of Labor ... 139

Figure 10: CHAT Object ... 143

Figure 11: CHAT Institutional Assessment System ... 150

Figure 12: CHAT Engagement with Institutional Assessment Environment ... 156

CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION Background and History

accreditation but also for internally motivated reasons such as strategic planning, benchmarking, and curriculum modifications (2014). Despite this trend, community colleges still report that achieving faculty buy-in, a crucial aspect of formative assessment, is difficult for many

assessment initiatives (Kuh et al., 2014). In addition, the report found that most institutions are not using their assessment results effectively – especially in the area of student learning

outcomes (Kuh et al., 2014) – which illustrates the need to address institutional culture regarding assessment. Institutional support, from faculty and administrators, is key to creating assessment programs that provide data-informed decisions that support the changing needs of higher

education.

Community college activities include not just degree transfers to four-year institutions, but also early college high school programs, professional development, personal development, vocational, and career and technical programs that have unique assessment needs that cannot be solely measured through standard persistence and completion metrics (Cohen et al., 2013). Practice-based or apprenticeship environments rely much more on authentic assessments such as portfolios, which are excellent tools for these non-curricular areas of study as they show that the student can accomplish the goals of the practice (Kvale, 2007). Student learning outcomes and other types of classroom assessment are of vital importance to the community college but given that 67% of community college faculty are part-time (Bickerstaff & Chavarin, 2018) they often do not have the capacity to complete a variety of assessments. Part-time faculty often have other jobs or situations that limit the amount of time they can spend on assessment activities

faculty, students, and outside interests. This study explores the community college assessment environment through the vantage point of the of part-time community college faculty. It investigates the system or systems that include the actors, institutions, tools, and other cultural aspects that influence assessment initiatives for this particular group.

Statement of the Problem

Assessment is an ever-present reality in higher education and encompasses everything from institutional and student success to classroom pedagogy. While assessment has always been a part of learning, the 1970’s brought about a change in assessment discourse that stemmed from a neoliberal economic philosophy (Ambrosio, 2013; Olssen & Peters, 2005). The trend toward a market-driven philosophy gave rise to the accountability movement in higher education which led to a greater emphasis on standardized testing and student learning outcome assessment (Ambrosio, 2013; Olssen & Peters, 2005).

In 2006, then Secretary of Education, Margaret Spellings, formed a commission to explore higher education and make recommendations for its future. The Spellings commission, as it became known, embraced the accountability movement that was said to “care little about the distinctions that sometimes preoccupy the academic establishment…instead they care – as we do – about results” (“A Test of Leadership: Charting the Future of U.S. Higher Education,” 2006, p. xi). The Spellings report references business methods throughout the document with a particular emphasis on job preparation.

professional development (Mundhenk, 2004). Success also means different things to different students since not all students go to community college to graduate instead they go to “acquire skills relevant to the careers they will pursue either directly out of community college or by way of a four year school” (Wyner, 2014, p. 3). These varying definitions of success are often related to obtaining a job upon completing their courses or how long it takes to obtain a degree.

Organizations such as The Aspen Institute and Achieving the Dream recognizes these different understandings of success. The Aspen Institution awards the Aspen Prize for

The importance of accountability data is also addressed through the Voluntary Framework of Accountability (VFA). The VFA is an initiative developed by the American Association of Community Colleges (AACC) to provide an accountability framework for community colleges (“About VFA,” 2019). The VFA framework helps community colleges measure student outcomes, progress, workforce outcomes, and completion and transfer measures – the data can drive benchmarking and strategic planning initiatives (“About VFA,” 2019).

Given the variety of student needs and success measures in a community college it is important to understand assessment and accountability within the specific community college context. The uniqueness of community colleges can be seen in many different areas – the first of which is in their commitment to open access and equity. Bailey et al. (2015) discusses the history of open access in this way - “access was important from two perspectives. The first perspective is the growing economic need for more educated workers – the need to find employment for the millions of returning veterans after World War II and the rise of the Baby Boomer generation” (p. 4). The second perspective is equity “in particular, in 1947 the Truman Commission noted the desirability of severing the strong link between socioeconomic

background and education achievement, advocated for increased education for African

Americans, and recommended an expansion of community colleges” (Bailey et al., 2015, p. 4). Community colleges focus on serving their community – everyone in the community - at an affordable cost. To serve this community the college not only offers associate degrees and two-year college transfer programs, but technical/vocational job training and certificates. There is also a focus on programs that provide life-long learning opportunities, which includes a range from one-shot classes all the way to degree programs.

from other higher education institutions (Bailey & Cho, 2010; Bailey et al., 2015; Mellow & Heelan, 2008). Community colleges also differ from other higher educational institutions in their demographics. For example, Mellow and Heelan state that “on average, community college students are older, poorer, more likely to be part-time and working, and more likely to be the first member of their family in college than students at four-year universities.” (2008, p. xv). North Carolina is one of the states that offers opportunity programs that entice younger college students – such as early college or college promise. These efforts are indicative of the wide ranging needs of community college students and the efforts made to meet those needs (“Career & College Promise | NC Community Colleges,” 2019; “Federal Grants Boost N.C.’s ‘Early College’ High School Push - Education Week,” 2016).

These unique aspects of the community college require a unique set of assessment plans and tools to understand their institutional needs and to understand the growing assessment environment as it is experienced by administrators, faculty, and students. The emphasis on student learning outcomes places faculty at the forefront of campus assessment, as the faculty are the ones who determine if students are meeting the expected outcomes of a specific course or curriculum. Classroom assessment is an integral part of higher education and with the

community college emphasis on teaching, it is an imperative. This is, however, not the only type of assessment done at the community college.

assessment efforts (Boser, 2010). Because of this, faculty should be aware of how to engage in the campus assessment environment – this participation makes them a part of the conversation. However, in practice the conversation often occurs without faculty, and in particular without part-time faculty input. Part-time faculty are often sidelined from the campus conversations due to their limited available time and indefinite institutional status, which can lead to overall faculty reluctance or inability to participate in the conversations (Contingent commitments: Bringing part-time faculty into focus, 2014; Danley-Scott & Tompsett-Makin, 2013a). Further, there is

little sharing of information and what occurs often trickles down through department meetings, emails and website notifications (Kuh et al., 2014). There is a lack of empirical research on this topic as well as a gap in the practice literature on how community colleges navigate the issue of part-time faculty and assessment. Understanding how part-time faculty, who are arguably the largest proportion of community college faculty, navigate their assessment environment will provide community colleges with insight on this particular group and how their interactions within the system may be or potentially could be influencing campus assessment environment and activities.

assessment – instead they are seen as transient and not invested in the learning process (Haviland, Turley, & Shin, 2011; Wang & Hurley, 2012).

Part-time faculty rarely have the time or institutional support to conduct authentic student assessments such as portfolios so the traditional multiple-choice tests are still the most prevalent choice (Danley-Scott & Tompsett-Makin, 2013a) even when they may not be the most

appropriate method. While there is research to show that teaching performance of part-time faculty is similar to that of full-time faculty, the ability to participate in an assessment

environment or perform assessment lags behind (Danley-Scott & Tompsett-Makin, 2013a). This gap in the literature, and in the areas of both research and practice, renders the part-time faculty invisible at a time when community colleges are performing significant assessment activities and developing institutional structures and protocol based upon an assessment environment ethos. Given the reliance on part-time faculty in the community college system it is important that community college leaders understand how this large population influences and is influenced by community college assessment practices.

Purpose and Guiding Research Questions

The purpose of this study is to better understand how part-time faculty perceive and navigate assessment and the assessment environment within their community colleges.

The research questions are:

1. How do part-time community college faculty perceive and describe the assessment environment within their community college?

Research Methodology

Qualitative research allows for unique community voices and experiences to be studied, and in this case a study exploring how part-time community college faculty perceive their environment is well suited for qualitative empirical work. There is a lack of qualitative studies that examine the ways in which part-time community college faculty perceive and engage with assessment in terms of attitude or perception and behaviorally. Assessment is an increasingly large part of the community college and as such the attitudes and perceptions that inform the community is an important area to explore. The research uses an instrumental case study

approach (Stake, 1995) that allows for in-depth interviews to provide a deeper understanding of the community college context – in this case an urban community college in the Southeast. Instrumental case studies allow researchers to explore questions by focusing on a particular bounded case (Stake, 1995) – such as part-time community college curriculum faculty. This research is considered a bounded case study or a “bounded system that exists independent of the research” (Hesse-Biber & Leavy, 2010, p. 263); therefore, the research does not purport

generalizability, instead the research seeks to provide particular information within a given system. Yin discusses binding the case as a way to manage the scope and keeping the study focused on a real-life situation and not an abstraction. (Yin, 2014, p. 34). Using a bounded study allows the research to maintain focus not just through the theoretical framework but through the study design itself. The study design will be outlined in greater detail in Chapter 3.

Theoretical Framework

organizational process and culture can be studied from the differing aspects as the subject navigates through the four CHAT areas of instruments/tools, rules, community, and division of labor to enact the object. Instruments, or tools, are the artifacts actors use to complete activities and reach desired goals. Within CHAT, rules are the cultural norms – both written and unwritten – that guide the actors in a given dynamic or context. These norms may be implicit – embodied in the actors in a subconscious manner or as subtext in a community – or explicit where the actors are conscious of the norms. The community is comprised of actors who work at different points in the system – roles that are exposed by exploring how actions occur within a system. The CHAT framework also allows for socio-cultural theories to be a part of the analysis – theories that impact the evolving social or relational dynamics of an evolving community.

Through CHAT researchers can explore the distributed nature of community knowledge or distributed cognition (Hutchins, 1993), the various communities of practice that are created in situated learning environments (Lave & Wenger, 1991), and how actors engage with the socio-material (Fenwick & Edwards, 2011; Latour, 1987). The CHAT framework allows the

discern and examines collective human behavior, focusing on members of a system, as a group, in learning a process or program is significant to this research.

CHAT focuses on objects or outcomes, which means a CHAT framework can follow a subject or subjects through to the completion of the outcome (or perceived completion). The choice of CHAT as a theoretical framework will allow an examination of an assessment

environment through the entirety of intersecting areas and the practices that shape these systems into a complex assessment environment. Thus, assessment can be conceptualized as a learning process that is influenced by a working set of explicit and implicit rules and norms, shared understandings, strategies by stakeholders for navigation of the ‘learning system’, and by better understanding how those elements converge into an outcome. The research questions will be addressed by CHAT in two different ways: one by examining the assessment environment as a whole through the perceptions of the faculty, two by examining how faculty engage with

assessment in this environment. The environment is explored through the policies, instruments, community,division of labor, and is seen as part-time faculty move through each of these areas as they engage of assessment.

Significance of Study

The Community College assessment environment is evolving and increasing in intensity. Faculty members, as the professionals who interact most directly with community college

students, are essential to any meaningful assessment in the community college. Given the predominance of part-time community college faculty members, it is essential to better understand how they discover and engage with assessment in their roles. Understanding how part-time community college faculty perceive and navigate assessment can impact future

meaningful ways in the assessment process. The study of part-time faculty involvement in assessment is vital in part because they account for 67% of community college faculty

(Bickerstaff & Chavarin, 2018). Part-time faculty engage in a significant portion of classroom work and student interaction which includes a variety of assessment initiatives. The nature of part-time faculty positions; however, means that part-time faculty may be less involved in the institution or professional opportunities. Some of these professional opportunities include attending faculty meetings, receiving institutional announcements, professional development courses, or meaningful participation in college initiatives. Missing these opportunities may lead to a disconnect between how assessment is understood, performed, and used in the institution at large. While there is some very good research on part-time faculty there is little on their place in the assessment environment.

Federal, state and local agencies as well as stakeholders want to understand how the community college is meeting its obligations to the larger community. Holistic research that looks at what is driving the data implementation and collection– the assessment environment – will help the community college gather the best possible metrics. As assessment continues to be an important factor in community colleges it is essential to understand how those who make assessment happen interact with their larger community as well as within the smaller contexts that comprise the community college environment. A cultural understanding can help everyone see how the community norms may influence assessment in ways both positive and negative. Using this information, assessment communities can then focus their endeavors using the voices of everyone involved in the system and better create assessment programs that do allow for data-informed decision making as opposed to performing assessment for assessment’s sake. This type of study can influence the perceived negative connotation of assessment to one that displays how it can work for all stakeholders and positively influence student, departmental, and institutional outcomes.

There is little empirical research in the literature on part-time community college faculty member’s engagement with assessment practices. Instead, existing research on community college assessment focuses on the general practice of assessment – best practices and how to guides (Alexander, Karvonen, Ulrich, Davis, & Wade, 2012; Andrade, 2011; Banta & Palomba, 2014; Boarer Pitchford, 2014; Bresciani, 2011; Friedlander & Serban, 2004; Haviland et al., 2011; Middaugh, 2010; Nunley et al., 2011). The research that does exist is primarily

members perceive, engage with, and understand assessment – it can help situate the part-time faculty in an assessment environment.

There are also a number of studies that explore faculty involvement with assessment practices but, again, with little emphasis on part-time faculty. The available studies explore how part-time faculty are (or are not) assessed at their institutions, how they view the act of

assessment, or how they do or do not participate in assessment. There is no research on the ways that part-time faculty perceive and actually engage with the assessment environment at a

community college – this is a crucial part of understanding and working to refine assessment environment and practice.

Higher education is being directed to provide data-informed reasons to show their return on investment – market forces and policies are pushing higher education into a neoliberal understanding of their place in our society (“A Test of Leadership: Charting the Future of U.S. Higher Education,” 2006; Ambrosio, 2013). Full-time faculty worry that the accountability movement may impact their academic freedom as well as require their work on items that are not in their purview. Policy makers express concerns that there are not enough educated graduates entering the workforce and not enough coherence or guided pathways that lead a student

efficiently from ‘entry’ to ‘employed’ (Bailey et al., 2015; Banta & Palomba, 2014; Boser, 2010; Ewell, 2008; Jin, Li, & Jian Chang, 2004; Shepard, 2000); however, part-time faculty are a minimal presence in the conversation.

better understanding their unique institutional culture and to enact meaningful changes to the assessment process. An assessment environment is dynamic and comprised of many moving parts and therefore must be explored as a living system. CHAT provides a holistic and realistic understanding of how actors participate in and navigate through an assessment environment by looking at the instruments, rules (implicit and explicit), community, and division of labor of the system.

Definition of Terms

For the purposes of this study it is important to define some key terms.

• Activity system – a bounded system that is comprised of community, rules,

instruments, and division of labor all acting with and against each other to reach a desired outcome. (Engestrom, 1987; Engestrom & Miettinen, 1999)

• Authentic assessment – assessment techniques that require students to

demonstrate understanding through the application of course content. These types of assessment include papers, presentations, and portfolios to name a few.

(Boarer Pitchford, 2014)

• Objective or traditional assessment – assessment technique used to evaluate

students factual knowledge about course content. A multiple choice exam is indicative of this type of assessment. (Boarer Pitchford, 2014)

• Part-time faculty – faculty hired to teach at the community college without

benefits and academic protections. This group is limited to the number of classes they can teach and are paid per class.

Summary

(CHAT) as a framework to explore and analyze the research problem. CHAT provides a

framework to explore the system – in this case the assessment environment - through the lens of part-time faculty. In particular how part-time faculty react to the rules and norms, artifacts, tools, and division of labor at work in the system. This research explores part-time faculty at a large, urban, Southeastern community college, and how they perceive, engage with, and understand the assessment environment.

Chapter Two provides a review of the literature including a brief history of higher education assessment and, in particular, assessment on community colleges. In addition, it will provide an overview of community college history as well as contemporary contexts. Next, the literature review presents a discussion on part time faculty in community colleges. Finally, Chapter Two provides an overview and explains the theory of CHAT, as well as, its strengths and weaknesses as a tool to understand activity systems and learning communities. Chapter Three describes the case study methodology used in this study and why it is appropriate for this project. The chapter also provides an account of the interview process, transcription process, coding, and analysis of the interviews. Chapter Four describes the participant stories as well as thematic findings based on the CHAT model. The thematic findings are based on off of the CHAT and free coding process. Chapter Five answers the research questions based on the

CHAPTER 2: LITERATURE REVIEW

The term community college is imbued with multiple meanings that reflect the varied nature, history, and philosophy of this particular type of educational institution. Terms such as junior college, technical college, and technical institution are all terms used to describe the community college. In this one type of institution community members can attend programs that prepare them to transfer to four-year institutions, allow them to gain a particular skill that may help them in the job market or take a class that fulfills an intrinsic need. The goal of a

community college is to meet the varied needs of the community it serves. A Brief History

In the latter 19th and early 20th century educators at prominent universities decided to leave the teaching of freshman and sophomore students to new institutions known as junior colleges (Cohen et al., 2013; Ratcliff, 1994). This shift allowed the traditional universities to emphasize research and theory as opposed to the “lower-division preparatory work” (Cohen et al., 2013, p. 6). During this same time period other educators envisioned a system where universities would offer “higher-order scholarship, while the lower schools would provide general and vocational education to students through age nineteen or twenty” (Cohen et al., 2013, p. 7). The mix of two-year college preparatory work and vocational education are evident in today’s community college institutions.

pragmatic and specific educational needs of people entering the workforce precisely because they could admit anyone into the school (Cohen et al., 2013; Gleazer Jr., 1994; Ratcliff, 1994). The mission to accept all community members shaped the curriculum to cover general academic education as well as vocational programs that would provide skills-based learning for the work place.

Community needs keep changing; however, and some contemporary community colleges have started granting baccalaureate degrees all-the-while offering high school completion and remedial classes. This “vertical expansion – the stretching of the community college curriculum down towards grades 11 and 12 and up toward the baccalaureate” (Cohen et al., 2013, p. 24) is an example of the ever-changing role of post-secondary education. Discussions on this vertical stretch center around the historical functions of community colleges versus their possible new role in the community (Cohen et al., 2013; McKinney, Scicchitano, & Johns, 2014). Teacher education is an excellent example of this aspect of the community college in that it can open up teaching programs to historically underrepresented groups (Park, Tandberg, Shim, Hu, & Herrington, 2018) which is in line with the community college meeting community needs. Proponents of the expansion say that community colleges are meeting community needs by offering affordable baccalaureate degrees that are otherwise not available to their community members while opponents hold concerns that this expansion will limit funding to the core curriculum and marginalize many community members (Cohen et al., 2013).

and the community college is in a unique position to fill this role. The mission to provide open access to all community members also gives the community college an important place in the education system.

Community Colleges: Mission and Vision

A significant part of the community college is their commitment to open access – the opportunity for anyone who desires an education to attend. The American Association of Community Colleges derives the community college mission from George B. Vaughn’s The Community College Story (1995), which states that:

The community college’s mission is the fountain from which all of its activities flow. In simplest terms, the mission of the community college is to provide education for

individuals, many of who are adults, in its service region. Most community college missions have basic commitments to:

• Serve all segments of society through an open-access admissions policy that

offers equal and fair treatment to all students; • A comprehensive educational program;

• Serve its community as a community-based institution of higher education;

• Teaching;

• Lifelong learning (p. 3).

George Vaughn’s description allows for community college missions to evolve to meet the changing community needs. The community college focus may include all or the majority of the following: career education, general education, collegiate or transfer education, remedial

education (Lorenzo, 1994; Townsend & Dougherty, 2006). These competing agendas may cause the organization to appear schizophrenic at times as leaders must ensure that the needs of various constituencies are met.

North Carolina has a strong history of community college activity starting with the person known as the founder of the North Carolina community college system Dr. W. Dallas Herring. Dr. Herring - a twenty-year North Carolina State Board of Education chair and creator of the first plan for industrial education - was from rural North Carolina and had a strong belief in education. In the book What Has Happened to the Golden Door, Dr. Herring noted that North Carolina needed educational institutions that provided alternatives to the University system, diverse institutions that were available at a reasonable price for the community (Herring, 1992, p. 11). This belief helped him recognize a need for vocational education for North Carolina

citizens – something that was lacking in the early 1950’s (“Oral History Interview with William Dallas Herring: Interview C-0034,” 1987). The governor during this time was bringing in more industry but there were still a preponderance of agricultural workers who would need training – and learn to work within a very different culture (“Oral History Interview with William Dallas Herring: Interview C-0034,” 1987). He believed that everyone should have access to an

the North Carolina Community College System, 2011). Herring wanted educators to understand

that “power, prestige, and quality” (“Oral History Interview with William Dallas Herring: Interview C-0034,” 1987) are no substitute for meeting student and community needs.

Open access: Who attends Community College

The American Association of Community Colleges 2018 fact sheet reports 12 million students are enrolled in community colleges (“Fast Facts - AACC,” 2018). The enrollment numbers display the diverse characteristics of community college students. The American Association of Community Colleges using data gathered from the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS) provides current information about the enrollment in

community colleges. The 2018 data shows that 37% of community college attendees are full-time, 56% are female, 47% are White, 13% are Black, and 24% are Hispanic (“Fast Facts - AACC,” 2018) The remaining percentages are divided among Asian/Pacific Islander, Native American, Non-resident Alien, Other/Unknown, or 2 or more races (“Fast Facts - AACC,” 2018). North Carolina community colleges align with national data showing that 37% of attendees are enrolled full-time, 59% of attendees are female, 56% of attendees are White, 21% percent of attendees are Black, and 10% are Hispanic (“IPEDS Data Center,” 2017).

However, the numbers do not tell the complete story, as Cohen et al. (2013) state: the community colleges reached out to attract those who were not being served by traditional higher education: those who could not afford the tuition; who could not take the time to attend a college full time; whose racial or ethnic background had constrained them from participating; who had inadequate preparation in the lower schools (p. 35) The students are very different from other post-secondary institutions in that they may be in certificate programs, non-credit classes, or vocational classes, among other learning

institution. Community colleges offer degrees, licensure, certificates, and the one-off classes that are a part of ongoing professional development. In essence, the students who enroll in a community college are as varied as the community itself.

A dominant theme that addresses the difference between traditional college students and those who attend community colleges is that of “citizen” (Vaughn, 1995, p. 17). Traditional students give their role as a student a priority over other roles which Vaughn describes as

“student-as-citizen” (1995, p. 17). The student-as-citizen role places scholarship and completing an education as the center of their life at that given time. Community college students are described as citizens first or “citizen-as-student” (Vaughn, 1995, p. 17) which suggests that the role of student is secondary to other responsibilities such as work and family. Current

information from the American Association of Community colleges also show that 62% of full-time and 72% of part-full-time community college students work which has an impact on the institution (“Fast Facts - AACC,” 2018). These differing roles have an impact on a number of factors such as when and what classes are taught as well as what student services and extra-curricular activities are offered.

projects location in Labor as opposed to Education. The emphasis is on education as a way to encourage job growth through skill development as much as through traditional curricular activities.

While workforce development is a large part of the community college mandate there is also a large demand for opportunities to transfer to four-year institutions. Some community colleges are looking at a reverse view of the transfer system – students will earn an associates in a specific area then transfer to a four year school to complete their studies (Mellow & Heelan, 2008, p. 188). This helps students because while many institutions will transfer in community college credits they are often counted as electives which means that transfer students may take longer to graduate than students who began at the four-year institution (Mellow & Heelan, 2008, p. 188). Another aspect of reverse transfer is used in North Carolina – students can credits from their four-year institution with those credits already earned at a community college – if the appropriate requirements are met then the students are given an associate’s degree (“Reverse Transfer | NC Community Colleges,” 2016). Community colleges are also creating guided pathways – a way for students to create, maintain, and complete a plan to lead them to the appropriate outcome. Guided pathways focus on “career and transfer outcomes” determined by the student and the institution (AACC, 2016). North Carolina also updated the Comprehensive Articulation Agreement (CAA) that governs the credit transfer between NC community colleges and NC public universities (“Comprehensive Articulation Agreement | NC Community

Bailey et al in their 2015 book Redesigning America’s Community Colleges discusses the current state of community college and suggests ways to improve various aspects of their current organizational structure. The authors describe the current model as a “cafeteria or self-service college because students are left to navigate often complex and ill-defined pathways mostly on their own” (Bailey et al., 2015, p. 13). This cafeteria style of education does not lend itself to in depth learning as students are jumping from course to course “unbundled” (Bailey et al., 2015, p. 19) without a lot of guidance from the institution. While the unbundled model may be more cost effective the authors suggest using a guided pathway approach as it is “likely to result in lower cost per successful completion” (Bailey et al., 2015, p. 19) per student. A guided pathway is an approach that will:

Engage faculty and student services professionals in creating more clearly structured, educationally coherent program pathways that lead to students’ end goals, and in rethinking instruction and student support services in ways that facilitate students’ learning and success as they progress along these paths (Bailey et al., 2015, p. 3). Crisp and Taggart (2013) discuss organizational programs that are designed to improve student success but found that there is not much “empirical evidence that demonstrates best practices or how to effectively implement these programs “ (p. 124). Other organizational “practices exist in a variety of forms and include learning communities, student success courses, and supplemental instruction” (Crisp & Taggart, 2013, p. 115) and these changing practices are rippling through community colleges.

defined high-demand classes as though that the business community thinks are appropriate (“Transforming Education | NC Governor McCrory,” 2015). The GPS or Guided Pathways plan takes a more nuanced view by using a networked improvement community (NIC) that is focused on a variety of aspects of student needs such as completion and transfer as well as employment (NC Student Success Center: NC GPS Network Overview, 2018). Dr. R. Scott Ralls, former President of the North Carolina State Board of Community Colleges and current President of Wake Technical Community College reported that “more than 40 percent of the wage earners in our state have been a student at one of our 58 community colleges in the past ten years” (2015, p. 1). This shows the impact the community college has on the state as well as offers some

influence on the future of the North Carolina community college curriculum. Governance

George Vaughn defines governance as “the process through which institutional decisions are made” (1995, p. 23) and those involved in governance explore the rules, regulations, policies, and other structures that govern the community college. Essentially community colleges consist of a president, vice-presidents, deans, department chairs, and other administrators while faculty serve on committees and councils (Vaughn, 1995). However, governance may be distributed or divided in a variety of ways including by department, support services, teaching faculty,

administrators with limited communication among the groups (Bailey et al., 2015, p. 145). Community colleges were not initially formed with shared governance in mind, instead they were “administered by leaders with seemingly unlimited authority reinforced by a board of trustees” (Alfred, 1994, p. 247). The community college president is historically tasked with administrative issues while the board of trustees influence institutional policy (Carlsen &

boards are more involved than others and their choice of president reflect the board’s role and power (Carlsen & Burdick, 1994; Vaughn, 1995). Boards can be appointed or elected depending on the state and appointed officials are often chosen by governors or other political leaders (Vaughn, 1995). There are also community colleges with state-level governing boards who are appointed by the governor although there is some concern that state-level control will

marginalize the differing needs of the disparate communities across the region (Vaughn, 1995). Over time more stakeholders became involved with community colleges such as state agencies, community members, and the faculty and staff. Changes in the community college system required faculty to take on more than teaching roles as they tackle assessment and planning in their institutions and these changes indicate a need for greater faculty governance (Alfred, 1994). In the 1990’s “students and stakeholders became more vocal in making their expectations for service and quality known” (Alfred, 2008, p. 81) while faculty and

administrators were in conflict over decision making responsibilities in the institution (Alfred, 1994, 2008). While faculty, staff, and students still push for inclusion in decision making there is still a “reliance on informal networks to interpret and communicate the why and how of decisions continues to be strong” (Alfred, 2008, p. 82) because many decisions are still made at the executive level. As community colleges grow and attempt to address the expanding and ever-changing needs of their communities “leaders will need to find ways to prevent size and complexity from turning institutions into educational bureaucracies and dispirited workplaces” (Alfred, 2008, p. 88). In addition it is important for governing bodies to be allowed to be proactive instead of reactive and encourage a “more collaborative approach to governance” (Bailey et al., 2015, p. 149) to better serve the institution and its stakeholders.

military service areas; establishing and closing colleges; providing individual Board of Trustees the laws and procedure they need to govern over program accountability, fiscal accountability and satisfaction of state priorities; establishing pay rates (“State Board of Community Colleges Code | NC Community Colleges,” 2018). Local boards have authority over personnel policies, educational guarantee, evaluation of presidents, and ensuring faculty meet the standards of the accrediting body among other duties (“State Board of Community Colleges Code | NC

Community Colleges,” 2018). While each community college in North Carolina does have its own governing body, they are answerable to the state board and work under the auspices of the state. North Carolina, now through the State Board, determines the path of the community college system as a whole and has had this role since 1963 (“Mission & History | NC

Community Colleges,” 2019). There are 58 colleges in the North Carolina system and it is the third largest community college network in the nation (“Mission & History | NC Community Colleges,” 2019) – their prominence both local and nationally is indicative of the strong state support and governance for community colleges.

Community College Pay and Tenure

The American Association of University Professors discussed faculty salaries in the 2018 Annual Report (The Annual Report on the Economic Status of the Profession, 2017-2018, 2018). The report states that the average salaries at Associate Degree granting institutions

are as follows:

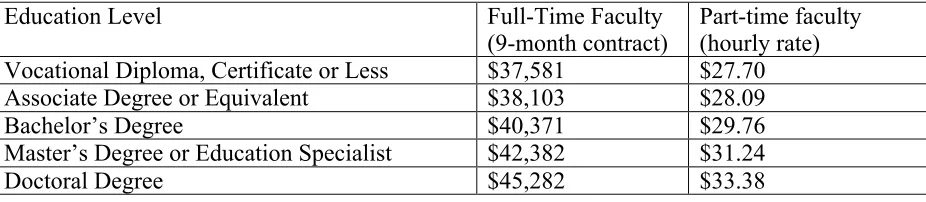

Table 1: Community College Faculty Average Salaries.

Category Average Salary

Professor 85,233

Associate 70,403

Assistant 60,728

Instructor 56,008

Lecturer 51,724

The same study found that the average pay per part-time faculty members is $16,215 at institutions with ranks and $12,863 at institutions without ranks (The Annual Report on the Economic Status of the Profession, 2017-2018, 2018).

North Carolina determines pay based on the following education levels of faculty: vocational diploma, certificate or less; associate degree or equivalent; bachelor’s degree; master’s degree or education specialist; doctoral degree (“NC Community College FY 2018-19 state aid allocations and budget,” 2018). Part-time faculty are paid based on educational levels as well, but their pay is designated as hourly or the “contact hour” – the contact hour is supposed to recognize work done outside of the classroom (“NC Community College FY 2018-19 state aid allocations and budget,” 2018). In March of 2015 the President of the North Carolina State Board of Community Colleges stated that our community college instructors “are among the worst paid in the country…and rank among the bottom third of states in the Southeast” which is also the lowest paid region (Ralls, 2015, p. 2). Table 2 shows the minimum salary faculty for North Carolina FY 2018-19.

Table 2: North Carolina Faculty Salary by Educational Level.

Education Level Full-Time Faculty

(9-month contract) Part-time faculty (hourly rate) Vocational Diploma, Certificate or Less $37,581 $27.70

Associate Degree or Equivalent $38,103 $28.09

Bachelor’s Degree $40,371 $29.76

Master’s Degree or Education Specialist $42,382 $31.24

Doctoral Degree $45,282 $33.38

Tenure or tenure track positions are desired but hard to come by in any institution; but in community colleges it is even more difficult. The American Association of University

faculty are tenured and approximately 5% are tenure track (Part-Time and Graduate Teachers, 2018). This places the majority of community college faculty in the part-time or adjunct status. North Carolina does not offer tenure to its community college instructors – they may work under one-year contracts for the first three years of service; however, this can vary by location given that governance is decentralized across the system. After three years some faculty members may receive longer contracts while others have their contracts terminated. This allows the college to hire more faculty with one-year contracts who have minimal job security – in addition some schools only offer one-year contracts to their faculty and that has significant consequences for institutional/departmental planning.

years over time. This means that faculty may not have the same protections in North Carolina as they would in states that favor unions.

Academic freedom in particular is hard to come by in the community college – even for full-time faculty members. Wake Technical Community College brought in industry

representatives to discuss what they expected their employees to learn and the college then built a curriculum around their needs; however, this was seen in part by faculty as diminishing their role as teachers and removing their freedom from the classroom (“The Casualties of the Twenty-First-Century Community College | AAUP,” 2010). Another aspect of this diminished role is seen in the lack of tenure offered to community college professors in most institutions. Job stability is lessened without tenure and it impacts a faculty members ability to pursue

controversial topics since academic freedom is not ensured. David Ayers (2010) suggested that community colleges have a greater emphasis on vocational education and job training – so much so that a community college initiative recommended by President George W. Bush was to be administered by the Department of Labor instead of the Department of Education. The mix of educational objectives – vocational and college transfer – causes competing demands between the ideals of higher education faculty, the business community, and the needs of the community as a whole.

Professional Development

Communities (FLC) and mentoring programs both of which provide faculty a person or group to help them navigate their roles (Banasik & Dean, 2016; Diegel, 2013; Meixner, Kruck, &

Madden, 2010). Professional Development is important for all faculty and in terms of part-time faculty “it is incumbent upon it (the institution) to provide the support structures and evaluation processes to ensure contingent faculty effectiveness” (Umbach, 2007, p. 111). Bailey et al. builds on Umbach by stating that “if colleges want to improve teaching and learning, they cannot afford to exclude adjuncts from the process” (Bailey et al., 2015, p. 169). Given the mission of community colleges as primarily teaching institutions then “the quality, preparation, and

pedagogical skills of the faculty have to be central” (Twombly & Townsend, 2008, p. 20). Bailey et al (2015) identified three critical areas for community college professional development: team facilitation; advising skills, and designing assessments (pp. 159–160). Designing assessments will help them ”measure complex learning outcomes (such as critical thinking), and that will help them think through how to use the results of learning assessments to improve instruction” (Bailey et al., 2015, p. 160).

Faculty may also have different professional development needs based on where they are in their career. Some faculty may need more classroom development where others may need to learn about growth opportunities – this means that any professional development opportunity should take into account faculty diversity (Williams-McMillan & Hauser, 2014, p. 625). The differing needs of instructors is also highlighted in Bickerstaff and Cormier’s (2015) research that shows “it may be difficult to meet the needs” (p. 79) of various faculty. Another study found that a key aspect to professional development is both formal and informal communication while stating that:

informal gatherings can be powerful for adjunct faculty. Participants enjoyed sharing teaching ideas and asking advice because these exchanges gave them more confidence to teach, established collegiality, and offered adjunct faculty an opportunity to feel like an important part of the department (Diegel, 2013).

Another aspect of informal learning is seen in the way faculty members share artifacts such as syllabi and other course materials (Bickerstaff & Cormier, 2015, p. 78). Sharing artifacts is another way to learn the expectations of an institution and to have models to use when developing their own materials. Informal communication via hallway interactions and

institutional events can help faculty members get to know each other as well as learn about the institution.

faculty experienced was connected to their lack of participation in institutional service activities through which they could learn about the institution, their program, and academic practice” (p. 548).

In the cafeteria model system professional development initiatives “are often top-down, designed and offered by the college’s administration with little input or feedback from the faculty themselves” (Bailey et al., 2015, p. 89) which may not meet the needs of faculty. This top down approach also feeds the isolated nature of faculty which doesn’t lead to job satisfaction. Instead a learning facilitation model may be more helpful to faculty just as it is for students. Learning facilitation allows them to “build and organize their conceptual understanding” (Bailey et al., 2015, p. 87) through discussions and activities.

Faculty

The demographics of community college faculty show that approximately two-thirds of all community college instructional faculty 54% are female and 79% are white (Gender, Race, and Ethnicity of Instructional Faculty Members, by Rank - The Chronicle of Higher Education,

2017). In addition only 2.7% of full-time and 2% of part-time faculty have a multi-year contract, while 18.1% of full time and 6.3% of part-time faculty have an annual contract (“Contract Lengths of Non-Tenure-Track Faculty Members - The Chronicle of Higher

Education,” 2015). The Chronicle Data also shows that North Carolina ranks 41 among the 50 states and the District of Columbia in faculty pay at two-year public institutions (“Compare the States - The Chronicle of Higher Education,” 2017). The data also shows that North Carolina is not investing in faculty in the same way as other states (“Compare the States - The Chronicle of Higher Education,” 2017).

one academic career coach told a new Ph.D. who wanted a research job but was considering a community college job that she may end up “ ‘trapped’ at the community college because of the workload” then the author goes on to state that “many people have had fulfilling careers in those environs – once they adjusted their own expectations, of course” (“The Professor Is In: Can a Community-College Gig Be a Launch Pad? | Vitae,” 2014). Popular culture, higher education magazines and websites, and career sites tend to marginalize the community college as

something you do as a last resort. Susan Twombly and Barbara Townsend (2008) echoed this sentiment in their research on community college faculty and why they receive little attention in the literature. They found that “not only do some 4-year college and university faculty members typically question the quality of community college courses and therefore the faculty members who teach them, they also tend to hold a general sense of arrogance about the status of 2-year college faculties relative to the status of university faculties” (Twombly & Townsend, 2008, p. 7). It is important to understand what it is like being a community college faculty member and in particular how reality, perception, and expectations impact their work. Community college faculty are not only faced with marginalization from their higher-education colleagues; many must also contend with their further marginalization as part-time faculty.

Part-time faculty

orientation, learning communities or the first-year experience (Contingent commitments:

Bringing part-time faculty into focus, 2014). At least half of part-time faculty work more than 50

hours a week (Jacobs, 2004) and they have limited access to professional development and rarely attend their faculty meetings (Contingent commitments: Bringing part-time faculty into focus, 2014; Jolley, Cross, & Bryant, 2013).

Full-time faculty have greater access to mentors, colleagues and administrators than their part-time counterparts – these relationship allow for engagement with an institution something that part-time faculty are missing (Danley-Scott & Tompsett-Makin, 2013a; Jolley et al., 2013; Thirolf, 2013). One study found that part-time faculty recognize the importance of the students education and success but feel that they are overlooked as a playing a part in student success (Jolley et al., 2013). Part-time faculty are often hired at the last minute and cannot plan on teaching future classes – it is a semester by semester existence (Jolley et al., 2013). Part-time faculty who complain about last minute decisions – or many other decisions – often find

themselves pushed out as there are others who need the work (Jolley et al., 2013; “The Casualties of the Twenty-First-Century Community College | AAUP,” 2010). These faculty members report feelings of isolation and marginalization – they feel they are separate from the full-time faculty (Jolley et al., 2013; Thirolf, 2013). In addition they are rarely evaluated in the classroom so they receive little support for the pedagogical practices – they are also at a disadvantage in student evaluations as they are often hard to reach outside of class due to their situation (Jolley et al., 2013).

accessibility impacts student success as well, as one study found that “a 10% increase in overall exposure to part-time faculty members resulted in a 1% reduction in the students likelihood of earning an associate degree” (Jaeger & Eagan, 2009, p. 186). Long hours, little job stability and little interaction with the institution all impact the part-time community college faculty member.

The lack of job stability and interaction may have an impact on student learning. Bailey et al (2015) describes the impact of part-time faculty on student learning in this way:

If colleges want to improve teaching and learning, they cannot afford to exclude adjuncts from the process…if the larger institution wants to be inclusive and respectful of adjunct faculty, the college’s leadership needs to work with departmental chairs to develop policies for part-time faculty employment. These might indicate the resources to which adjunct faculty are entitled (including office space, administrative support staff, and professional development) (p. 169).

The authors also found the inclusive spaces create a better workplace for part-time faculty which in turn enhances the student experience.

The community college faculty have a large impact on student success no matter the program area but given the large percentage of community college faculty that are part-time their input may be hard to acquire. However, the renewed emphasis on data-informed decisions at the community college require a renewed emphasis on assessment in these institutions, which makes the input of part-time faculty even more relevant given their large numbers in the institutions.

Assessment in Higher Education

History

Assessment is a broad category that encompasses not just student learning and

development but the “entire process of evaluating institutional effectiveness” (Banta & Palomba, 2014, p. 2). The earliest work on assessment is documented in the early 1930s and focuses on student learning as well as student maturation (Ewell, 2002). Program evaluation is another key moment in the assessment tradition with applications for “strategic planning, program review, and budgeting” (Ewell, 2002, p. 3). A significant part of the assessment history is in the area of mastery learning which is learning “based on agreed upon outcomes, assessing and certifying individual student achievement” (Ewell, 2002, p. 4). Mastery learning was useful in adult and professional education and gave rise to the idea of prior learning assessment (Ewell, 2002, p. 4). Mastery learning paved the way for Alverno College which implemented a student learning outcome survey for their alumni that would explore how their alumni were performing after graduation (“Assessment at Alverno College.,” 1978; Banta & Palomba, 2014). The “assessment as learning” (Banta & Palomba, 2014, p. 4) that Alverno created is driven by their mission

statement in that they want to ensure that they stay on track with their desired goals.

Peter Gray (2002) discussed the philosophies behind assessment that includes rationalist, positivist, scientific, objectivist, and subjectivist models that influence the way assessment is performed. He continues by discussing how these models influence student learning, educational practice and experiences, evaluation and decision making (Gray, 2002). Historically assessment has changed as these philosophies change which takes us up through the accountability

synonymous, with the latter usually thought of as summarizing student test performance and assigning grades” (Fitzpatrick et al., 2011, p. 41). It was in the 1950’s and 1960’s that education saw “considerable efforts…by teaching educators how to state objectives in explicit, measurable terms” (Fitzpatrick et al., 2011, p. 42). Evaluation essentially became a career in the 1970’s and 1980’s with more research and implementation which leads to the present where it is now embedded in education (Fitzpatrick et al., 2011).

Post-secondary education and Voluntary Systems of Accountability

Assessment in post-secondary education takes many forms from the macro (instructional) level to the micro (classroom) level (Anderson, 2004). At the macro level assessment is

designed to drive decisions on enrollment practices, engagement, productivity, retention, and benchmarking to name a few (Anderson, 2004; Banta & Palomba, 2014; Ewell, 2002). Micro level assessment can be seen in student learning outcomes and teacher evaluations – assessment that can impact classroom practices and student performance (Banta & Palomba, 2014; Boarer Pitchford, 2014; Ewell, 2002). Assessment is an incredibly helpful formative tool for

community colleges; however, assessment in post-secondary institutions is driven by outside factors such as accreditation and performance funding. These macro and micro level

Do,” 2015). Prior learning assessments allow students to earn college credit for “college-level learning acquired from other sources, such as work experience, professional training, military training, or open source learning from the web” (“CAEL - Prior Learning Assessment,” 2015) while competency based education is based on the demonstration of learned skills (“CAEL - Competency-Based Education,” 2015). The focus of these programs is adult education and a recognition of lifelong learning focused on the workplace – something that aligns with many views of post-secondary education.

Foundations often work and help support community colleges with programs such as Achieving the Dream (ATD) – a national initiative put together by the Lumina Foundation in 2004 (“History | Achieving the Dream,” 2019). ATD has a strong focus on data-driven decision making, teaching and learning, and pathways coaching that is designed to “accelerate and advance your student success agenda” (“Our Services | Achieving the Dream,” 2019). In North Carolina, Central Piedmont Community College (CPCC), Davidson County Community College, Gaston College, and Stanly Community College among several others are or were members of the “Achieving the Dream: Community Colleges Count! Initiative designed to identify new strategies to improve student success, close achievement gaps, and increase retention rates” (“What is Achieving the Dream? (ATD) — Central Piedmont Community College,” 2015). Davidson County Community College won the 2018 Community College Financial

competency-based instruction in a particular program and provide data on its success (“ETA News Release: Vice President Biden announces recipients of $450M of job-driven training grants,” 2013). ATD and other foundations offer significant awards to community colleges, but these awards and others are often based on institutional assessment and accountability data.

Accountability data is an important part of institutional assessment and the Voluntary Framework of Accountability (VFA) is an initiative developed by the American Association of Community Colleges (AACC) to provide accountability framework for community colleges (“About VFA,” 2019). The VFA framework helps community colleges measure student outcomes, progress, workforce outcomes, and completion and transfer measures – in addition, the data is shared and can drive benchmarking and strategic planning initiatives (“About VFA,” 2019). The Aspen Institute, which offers a $1 million dollar prize to community colleges based on their publicly available data, models their data definitions after the VFA (“Selection Process - The Aspen Institute’s College Excellence Program,” 2019). The impact of measurable

assessment data cannot be overstated for the success of community colleges; however, assessment environment and attitudes can often be a hurdle for institutions.

This data is also imperative for accreditation purposes as accrediting bodies depend on assessment to certify an institution. The Southeastern Association of Colleges and Schools (SACS) requires institutions to provide a compliance certification that includes institutional self- assessments as well as a Quality Enhancement Plan (QEP) that includes assessment (The

Principles of Accreditation: Foundations for Quality Enhancement, 2017). The QEP in

particular must have

initiate, implement, and complete the QEP; and (e) includes a plan to assess achievement (The Principles of Accreditation: Foundations for Quality Enhancement, 2017, p. 19). This means that institutions must also show that they designed, implemented and acted upon assessment initiatives that impact student learning.

Post-secondary institutions use assessment in different ways – for example regional or specialized programs drive some types of assessment while accreditation is a driver across institutions (Kuh et al., 2014). Studies also found that a variety of assessment are used to

evaluate students such as national surveys, rubrics, and employer surveys (Kuh et al., 2014). The variety and implementations of assessment have an impact on how faculty address the issue in their institution.

Culture and Faculty

Faculty often consider assessment from an instrumentalist point of view – they fear that the assessment is performed with little to no regard for those being assessed and the goal is to complete the assessment, not to actually impact learning or to make day to day work life easier (Falchikov & Boud, 2007). There are also contradictions in what assessment means for higher education and what it means for vocations, which has a large impact on how community colleges assess their classroom practices as well as assessing their learners (Kvale, 2007). Assessment is often viewed as a top-down initiative something that is much more desired by administrators and funders than faculty (Anderson, 2004; Banta & Palomba, 2014).

aspects from the macro to the micro level are ignored in the accountability movement – aspects that impact every part of the institution (Billett, 2004; Boser, 2010; Fenwick, 2009; Shepard, 2000).

Neoliberalism and Accountability

Assessment as an educational necessity was created from a neoliberal economic

philosophy that champions policies that requires schools to be subject to the same market-driven forces as business (Ambrosio, 2013; Levin et al., 2006; Olssen & Peters, 2005). Subsequently, they must provide data that shows the schools are meeting the market demand. Administrators started asking higher education institutions to show a measurable impact on student learning and as such created an emphasis on standardized testing and student learning outcome assessment (Ambrosio, 2013; Olssen & Peters, 2005).

The Spellings commission, a 2006 assessment initiative, embraced the discourse of neoliberalism as seen in report passages that state that consumers “care little about the

distinctions that sometimes preoccupy the academic establishment…instead they care – as we do – about results” (“A Test of Leadership: Charting the Future of U.S. Higher Education,” 2006, p. xi). The Spellings report references business methods throughout the document with an