THIS PLACEMENT HANDBOOK CONTAINS INFORMATION SPECIFIC TO THE DOCTORATE IN COUNSELLING PSYCHOLOGY. IT MUST BE READ IN CONJUNCTION WITH THE CURRENT FACULTY OF HUMANITIES POSTGRADUATE STUDENT HANDBOOK PROVIDED ON ENROLMENT AND THE PROGRAMME HANDBOOK..

DOCTORATE IN COUNSELLING PSYCHOLOGY

(D.Couns.Psych.)

PRACTICE PLACEMENT HANDBOOK –

Information for trainees, practice placement educators and supervisors

Address:

Manchester Institute of Education Ellen Wilkinson Building

The University of Manchester Oxford Road

Manchester M13 9PL

Tel: 0161 275 3466

2

CONTENTS LIST PAGE

Welcome 3

Background to the Programme:

How does the placement link with work at the University? Information for the practice placement educator

Arrangements whilst the trainee is on placement Supervision Appendices 4 12 35 53 68 77

3

WELCOME

Many thanks for agreeing to work as a practice placement educator or supervisor with one (or more!) of our trainee counselling psychologists. We appreciate your commitment to their work and training, and the time that you are devoting to learning about your roles with us. The intention of this handbook is to give you an overview of the Programme that the trainee is undertaking with us and identify further information in relation to the programme should you require it. We also list contact numbers of main staff involved in the programme should you need to get in touch with us and finally we outline the roles and responsibilities of the practice placement educator and supervisor alongside those of the University and the trainee psychologist.

The Doctorate in Counselling Psychology (D.Couns.Psych.) is validated by the Health and Care Professions Council (HCPC) and accredited by the British Psychological Society (BPS), as an initial professional training programme for Counselling Psychologists. As such, it is expected that each successfully completing student will be eligible to begin working as a confident and competent practitioner, who has the ability to operate successfully in relation to consultation, assessment, intervention, training and research, and also contribute to the development of the profession of counselling psychology.

Although we outline issues in relation to the Health and Care Professions Council Standards of Education and Training and Standards of Proficiency, the following documents might be helpful to you for future reference alongside documentation from the British Psychological Society.

HCPC

Standards of Proficiency: Practitioner Psychologists. Standards of conduct, performance and ethics. Guidance on conduct and ethics for students. BPS

Code of Ethics and Conduct.

The Division of Counselling Psychology’s Professional Practice Guidelines. Guidelines for minimum standards of ethical approval in psychological research.

This year has seen a number of exciting new developments to the Programme, Clare has moved on to a new post with the Fire Fighters Charity and we welcome our new colleagues Tony Parnell and Laura Cutts to the team alongside Terry.

Finally, the D.Couns.Psych. are delighted that you have agreed to work alongside us in supporting the training of our students and we look forward to our work together. We have identified a number of ways in which we seek your feedback regarding this work, but please feel free to contact any one of us at any point.

Dr Terry Hanley CPsychol AFBPsS Programme Director

4

BACKGROUND TO THE PROGRAMME:

INTRODUCTION TO COUNSELLING PSYCHOLOGY

The following content is taken from the Standards for Doctoral programmes in Counselling Psychology published by the British Psychological Society (2010). It has been included to provide students with a broad introduction to the developing profession of Counselling Psychology and to outline the overarching aims of such a programme. These provide a foundation to the more programme specific introduction provided in the next section.

The profession of counselling psychology is a distinctive profession within psychology whose specialist focus links most closely to the allied professions of psychotherapy and counselling. counselling psychology pays particular attention to the meanings, beliefs, context and processes that are constructed both within and between people and which affect the psychological well-being of the person.

The Programme Philosophy:

The University of Manchester’s Doctorate in Counselling Psychology is a pluralistic therapeutic training programme that acknowledges that “any substantial question admits of a variety of plausible but mutually conflicting responses” (Rescher, 1993, p.79; see also Cooper and McLeod [2011] for a discussion of pluralistic counselling and psychotherapy). It adopts a stance that values the social and political contexts in which the profession of counselling psychology has developed and in which therapeutic work is undertaken. Furthermore it values the phenomenological intersubjective experience of those involved in the therapeutic process. With this in mind, the person seeking support is viewed as an active agent of psychological change with whom any intervention should be centred (see Bohart and Tallman [1999] and Duncan et al [2004] for more discussion on client agency within therapy). Such a collaborative view values the scientist-practitioner model of professional practice (e.g. Lane & Corrie, 2006) and is increasingly supported by the research exploring the effectiveness of psychological therapies (e.g. Wampold, 2001; Cooper, 2008).

The Skilled Helper framework (Egan, 2010) is used as a harnessing feature to the programme. This is a three stage problem management and opportunity development framework that emphasises (1) exploration, (2) insight, and (3) action. In doing so it embraces the notion that there are common factors to successful therapeutic relationships. In particular, it aims to sensitise trainees to the three components conceptualised by Edward Bordin (1994) within their work as counselling psychologists. These are that a therapeutic alliance will consist of:

(1) a mutual agreement between the therapist and client on the goals of therapy, (2) a mutual agreement between the therapist and client on the tasks of therapy, and (3) an emotional bond between the therapist and client.

In such a framework, the agreement between both (or all) parties upon the therapeutic activity becomes paramount when considering the overall effectiveness of any intervention. This framework acts as scaffolding for trainees to make sense of the numerous tensions that are present within the core therapeutic models that are presented within the programme. Within the first year of the programme, trainees are supported in understanding the key postulates of humanistic psychology (Bugental, 1964) and the core competencies of humanistic counselling (Roth, Hill & Pilling, 2009). This approach has its foundation in the

5 person-centred approach (e.g. Gillon, 2007) and introduces trainees to the model of psychological change first proposed by Carl Rogers (1951; 1959) and subsequently developed by contemporary thinkers (e.g. Cooper, 2007). Fundamentally, the emphasis of this year is upon the importance of the relationship within therapeutic work.

Within the second year, trainees will consider the core competencies of cognitive behavioural therapy (Roth & Pilling, 2007). Trainees will be encouraged to reflect upon therapeutic interventions and models of personality development in line with the original proponents of the approaches (e.g. Beck, 1976; Beck et al. 1979; Ellis, 1962) and more contemporary thinking (e.g. Ost, 2008; Trower et al, 2011). These models of change will be considered in relation to those presented within the first year of the programme and the differences and similarities between them reflected upon in relation to the Skilled Helper framework.

In addition to input around the above therapeutic approaches, trainees will engage in professional input activities focusing upon generic professional issues. These will include coverage of core Standards of Proficiency (HPC, 2009), lifespan development (e.g. Sugarman, 2001), and models of psychopathology and psychopharmacology (e.g. Davey, 2007; Bentall, 2009). These will enrich the experience of the training input and reflect upon core components to therapeutic practice outside of the training environment.

Trainees will be encouraged to learn through doing with regular skills activities and video assessed work. Complementing the structured theoretical input and practical sessions will be substantial placement activities (a minimum of 450 hours working as a trainee counselling psychologist). These will be delivered in a minimum of two placement settings and cover a minimum of two modalities (e.g. individual therapy, group work, work with couples etc). They will be well supported by appropriate placement providers and trainees will be required to attend supervision at a ratio of 1 hour per 8 client hours as a minimum.

Personal development plays a major part within the programme. Trainees are encouraged to develop as reflective practitioners and to regularly consider their own growth during the programme. Additionally, trainees are required to undertake 40 hours of personal therapy. It is anticipated that these personal development activities will help to consolidate trainees’ integration of psychological understanding with personal learning, their understanding of how the scientist practitioner works alongside being a reflexive practitioner and in a ‘way of being’ that proves congruent with personal values and allows appropriate navigation of professional roles.

Assessment will reflect upon the philosophical, theoretical and practical components to the programme. This will take the form of theoretical papers, case studies and practice reports related to placement activities. It will also involve conducting a substantial research project to be presented as a final thesis. Each of these pieces will represent a contribution to the body of psychological knowledge regarding the discipline of counselling psychology.

The key aim of an accredited programme is to produce graduates who will:

1. be competent, reflective, ethically sound, resourceful and informed practitioners of counselling psychology able to work in therapeutic and non therapeutic contexts;

2. value the imaginative, interpretative, personal and intimate aspects of the practice of counselling psychology;

6 4. understand, develop and apply models of psychological inquiry for the creation of new knowledge which is appropriate to the multi-dimensional nature of relationships between people;

5. appreciate the significance of wider social, cultural and political domains within which counselling psychology operates; and

6. adopt a questioning and evaluative approach to the philosophy, practice, research and theory which constitutes counselling psychology.

(SET4.2) References

Beck, A. (1976). Cognitive therapy and the emotional disorder. New York: International University Press

Beck, A., John, R., Shaw, B., & Emery, G. (1979). Cognitive Therapy of Depression. New York: Guildford Press

Bentall, R. (2009). Doctoring the mind: why psychiatric treatments fail. London: Allan Lane. Bohart, A., & Tallman, K. (1999). How clients make therapy work: The process of active self healing. Washington DC: American Psychological Association.

Bordin, E. (1994). Theory and Research on the Therapeutic Working Alliance: New Directions. In A. Horvath & L. Greenberg. (eds). The Working Alliance: Theory, Research, and Practice. New York: John Wiley & Sons

Bugental, J. (1964). The third force in psychology. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 4(1), 19-25

Cooper, M. (2008). Essential Research Findings in Counselling and Psychotherapy Research: The Facts are Friendly, London: Sage

Cooper, M. (2007). Developmental and personality theory. In M. Cooper, M. O’Hara, P. Schmid & G. Wyatt (eds). The Handbook of Person-Centred Psychotherapy and Counselling. London: Palgrave, pp.77-92

Cooper, M. & McLeod, J. (2011). Pluralistic Counselling and Psychotherapy. London: Sage Davey, G. (2008). Psychopathology: Research, Assessment and Treatment in Clinical Psychology. London: Wiley Blackwell

Duncan, B., Miller, S. & Sparks, J. (2004). The Heroic Client: A revolutionary way to improve effectiveness through client-directed outcome-informed therapy. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Egan, G. (2009). The Skilled Helper: A Problem-management and Opportunity Development Approach to Helping (Ninth Edition). Thompson Learning

Ellis, A. (1962). Reason and Emotion in Psychotherapy. New York: Lyle Stuart Gillon, E. (2007). Person Centred Counselling Psychology, London: Sage HPC. (2009). Standards of Proficiency. London: HPC

Lane, D.A. & Corrie, S. (2006). The modern scientist practitioner: A guide to practice in psychology. Hove: Brunner-Routledge.

Öst, L. (2008). Efficacy of the third wave of behavioral therapies: A systematic review and meta-analysis, Behaviour Research and Therapy, 46 (3), 296-321

Rescher, N. (1993). Pluralism: Against the demand for consensus. Oxford: Oxford University Press

Rogers, C. (1951). Client Centred Therapy. Boston: Houghton & Mifflin

Rogers, C. (1959). A theory of therapy, personality and interpersonal relationships as developed in the client-centered framework. In S. Koch (Ed.), Psychology: A study of Science. New York: McGraw-Hill

Roth, A., Hill, A., & Pilling, S. (2009). The competences required to deliver effective

Humanistic Psychological Therapies. Online at: http://www.ucl.ac.uk/clinical-psychology/CORE/humanistic_framework.htm (Accessed 11.2.11)

7 Roth, A. & Pilling, S. (2007). The Competences Required to Deliver Effective Cognitive and Behavioural Therapy for People with Depression and with Anxiety Disorders. London: Department of Health.

Sugarman, L. (2001). Life-span development: frameworks, accounts, and strategies (Second Edition). New York: Psychology Press

Trower, P., Jones, J. Dryden, W. & Casey, A. (2011). Cognitive Behavioural Counselling in Action (Second Edition). London: Sage

Wampold, B. (2001). The Great Psychotherapy Debate: Models, Methods and Findings. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates

8

INTRODUCTION TO THE D.COUNS.PSYCH

The Doctorate in Counselling Psychology (D.Couns.Psych) is a full time programme situated in the Manchester Institute of Education, University of Manchester. The programme has been approved by the Health and Care Professions Council (HCPC) and accredited by the British Psychological Society (BPS). It therefore aims to provide an initial professional training programme for Counselling Psychologists working within the United Kingdom (UK). Each of units listed in the following sections outlines learning objectives and associated standards of proficiency (SoP) as required by the HCPC (SET4.1).

The programme consists of three major elements that fit within the professional body’s requirements for courses of this kind. These are ‘Theory’, ‘Research’ and ‘Practice’ and each element is viewed with equal importance throughout (SET6.3). It is noteworthy that in conceptualising these divisions, (1) the ‘Theory’ component encapsulates philosophical underpinnings of therapeutic work, psychological theory and professional expectations of health professionals (2) the ‘Research’ component reflects upon vital the importance of research and evaluation within everyday therapeutic practice and supports trainees in conducting a piece of empirical research, and (3) the ‘Practice’ component includes development and discussion of therapeutic skills, the delivery of supervised placement work as a Counselling Psychologist and personal therapy. Each one of these areas is elaborated upon further within this handbook. It is expected that each successfully completing student will be eligible to begin working as a confident and competent practitioner, who has the ability to operate successfully in a variety of different roles (e.g. therapist, trainer and researcher) and by doing so contribute to the development of the profession of Counselling Psychology. During the first two years of the programme the typical week consists of three days direct input at the University and two days set aside for private study and placement activities. During Year 3 trainees are expected to complete a research thesis. With this in mind, a majority of the trainee’s week is self-directed learning with practice issues and discussion around research issues being provided each Friday. Further information about the structure of the course is provided later in this document.

Programme Aims

The programme aims to:01.

Provide a structured programme of study, which reflects upon practice at an advanced level. This will proactively support candidates’ contributions to the development of new methodologies, techniques and concepts relevant to Counselling Psychology practice and encourage individuals to produce peer reviewed research output (SET4.7).

02.

Support the development and transformation of existing professional experience and expertise into research outcomes that will extend knowledge, understanding and practice in Counselling Psychology. Particular focus will be placed upon*: a) the identification and assessment of health and social care needs,

b) the formulation and delivery of plans and strategies for meeting health and social needs,

9 c) the critical evaluation of the impact of, or response to, the registrant’s actions

(* factors directly stipulated by the HCPC) 03.

Provide candidates with opportunities to deepen and broaden knowledge and understanding of the professional, psychological and ethical dimensions of their own practice and significant related practices to Counselling Psychology. In addition to a major emphasis on the psychological theories of change*, particular focus will be placed upon*:

a) the autonomous working and accountability of health professional (SET4.6),

and,

b) the complex nature of professional relationships with stakeholder groups (* factors directly stipulated by the HCPC)(SET4.3) 04.

Generate new perspectives on the engagement between Counselling Psychology practice and the multiple, complex, diverse and unpredictable contexts of ‘application’.

05.

Enhance the continuing professional and personal development across a range of contexts. Furthermore the students will contribute to the development of a range of professional competencies (theoretical understanding, research skills and therapeutic practice) in Counselling Psychology*.

(* factors directly stipulated by the HCPC and BPS)

All work will be assessed in accordance with the University’s ordinances and regulations for examination at Doctorate Level (SET6.2, 6.6).

For Whom?

The D.Couns.Psych. is for psychologists who have an interest in developing their therapeutic skills. As a practitioner psychologist the trainees will extend their existing theoretical understanding of the applied psychology arena, enhance their therapeutic skills and conduct a piece of original research.

Entry Requirements (Basic Criteria For Entry) Applicants are normally required to have (SET2.5):

a 2.1 honours degree or above in psychology. For any candidates with a lower classification we would also require an additional Masters level qualification where the student was awarded at least a grade B or equivalent in their dissertation

have a Certificate in Counselling or equivalent qualification and some professional experience of using their counselling skills

have the capacity to undertake research to Doctoral level

Graduate Basis for Chartered Membership (GBC*) with the British Psychological Society (BPS)

10 English GCSE grade C or above, or IELTS - 7.5 or above with a minimum of 7.0 in

each separate sub-category (if English is not the first language) (SET2.2) Satisfactory Criminal Convictions Check (SET2.3)

Accreditation of prior or experiential learning (APL or APEL) towards the D.Couns Psych. award will be awarded in line with the policy outlined by the School of Education, University of Manchester (SET2.6) web link-

http://www.humanities.manchester.ac.uk/tandl/policyandprocedure/documents/staff_apel_gui delines.doc

Admission procedures will be delivered in accordance with the University’s Equality and Diversity policies (SET 2.7). web link-

http://documents.manchester.ac.uk/DocuInfo.aspx?DocID=8361

*Please note that GBC was previously referred to as GBR (Graduate Basis for Registration). The two are the same membership, and we will accept both as proof of appropriate prior training.

Where we are situated

The D.Couns.Psych. programme is situated in the Manchester Institute of Education, within the School of Environment, Education and Development, Faculty of Humanities. It is supported by the University of Manchester Library, the largest University library outside Oxford. In the University Funding Council’s research assessment exercise, the Institute (then the School of Education) achieved a high grade and ranking, in recognition of the high quality and quantity of its research activities. The vibrant research activity within the Group emphasises relevance to educational practice. The Head of the Institute of Education is Professor Dave Hall (SET3.1).

The Institute General Office in on the third floor (B Wing) of the Ellen Wilkinson Building. Main contacts for enquiries is Debbie Kubiena (Senior Postgraduate Research Administrator). The contact information for administrative support for the D.Couns.Psych. is noted on the front of this handbook. The Head of School Administration is Jayne Hindle.

Key Staff (SET3.5, 3.6)

Programme Director (SET3.2, 3.4):

Terry Hanley CPsychol, AFBPsS, PhD, MSc, MA, BSc (Hons)

Terry is a Lecturer in Counselling Psychology at the University and Editor of Counselling Psychology Review. He is also a HCPC registered Practitioner Psychologist (Counselling) and is chartered by the BPS. Much of his practice has focused upon working with young people within non-clinical settings (e.g. school-based therapy and online therapy). Additionally, he has research interests in the development of counselling psychology training, therapeutic work with young people and the development of practice-based evaluation strategies.

Core Staff

Tony Parnell CPsychol, AFBPsS, CSci, MSc, BSc (Hons)

Tony is a Lecturer in Counselling Psychology at the University. He is a HCPC Registered Practitioner Psychologist and Chartered Counselling Psychologist with the BPS. He has a private therapy practice with an emphasis on Trauma and PTSD. He is a Registered Applied

11 Psychological Practice Supervisor with the BPS. He is also an External Examiner for the British Psychological Society, Qualification in Counselling Psychology. His research interests are in PTSD and predisposition, Trauma and attachment, the use of metaphor in therapy, Mindfulness and post-traumatic growth.

Laura Cutts MBPsS, BSc (Hons)

Laura is a Lecturer in Counselling Psychology at the University. Her clinical practice has been focused in NHS and third sector settings, and she is currently based in an NHS

Complex Primary Care Psychology Service. Her research interests include social justice and counselling psychology, the integration of research and practice in psychology, and the identity of the counselling psychology profession.

The Programme is supported by colleagues throughout the Manchester Institute of Education. These include:

Kate Adam CPsychol – Kate provides regular case discussion sessions on the programme. Research Supervision and professional input will be provided by:

Dr Liz Ballinger, PhD

Dr Richard Fay, PhD, MEd (TESOL), Dip TEFL, BA (Hons)

Professor Neil Humphrey, CPsychol, Ph.D., PG Cert, BA (Hons) Psychology Dr Graeme Hutcheson, PhD.

Dr Garry Squires, CPsychol, DEdPsy., MSc, BSc, Med (HCPC Registered Practitioner Psychologist [Educational])

Dr William West, PhD

Additional professional input and specialist support will come from:

The Programme Directors for the Doctorate in Educational and Child Psychology (D.Ed.Ch.Psych), Dr Cathy Atkinson CPsychol, Caroline Bond CPsychol and Professor Kevin Woods CPsychol.

The Programme Director for the Doctorate in Educational Psychology (D.Ed. Psych.) is Dr Garry Squires CPsychol.

The Counselling courses staff. Including Peter Jenkins (Director of the MA in Counselling), Dr Liz Ballinger (Lecturer in Counselling), George Brooks (Lecturer in Counselling) and Dr William West (Director of the Doctorate in Counselling).

All core staff are active in Continuing Professional and research Development activities (SET3.7, 4.4).

Programme Administrator:

In addition to course publicity queries about the programme will be directed in the first instance to (SET2.1):

Debbie Kubiena | Senior Postgraduate Research Administrator | Room B3.10 | Manchester Institute of Education (MIE) | School of Environment, Education and Development | Ellen Wilkinson Building | The University of Manchester | Oxford Road | Manchester M13 9PL | Tel +44 (0)161 275 3466

12 Please note that the Faculty Research Handbook (available from the Scool Office) provides detailed information about all programmes in the Faculty of Humanities, together with the research activities of members of staff.

HOW DOES THE PLACEMENT LINK WITH WORK AT THE UNIVERSITY?

We want you to be clear about how your work with the trainee will fit into their work here with us at the University (SET 5.11) in terms of programme content, learning outcomes and structure of the programme. The full units are listed in appendix 1 in this handbook we only include those most relevant to the trainee’s work in this section.In years one and two the trainees will be with us at the University for three days (Monday, Tuesday and Friday) for the professional input of the programme covering theory, research, practice and case discussion. They are therefore available for practice for two days (2013 – 14 - Wednesday and Thursday), these days are also used for independent study. The third year of the course will mark a shift in the delivery of the programme where trainees are only with us at the University on a Friday, this period of time will focus upon (1) conducting and writing up a piece of original research, and (2) provide Documentary Evidence of therapeutic activities.

During every Friday scheduled in the semester, trainees from each cohort will attend the University for reflection on their case work.

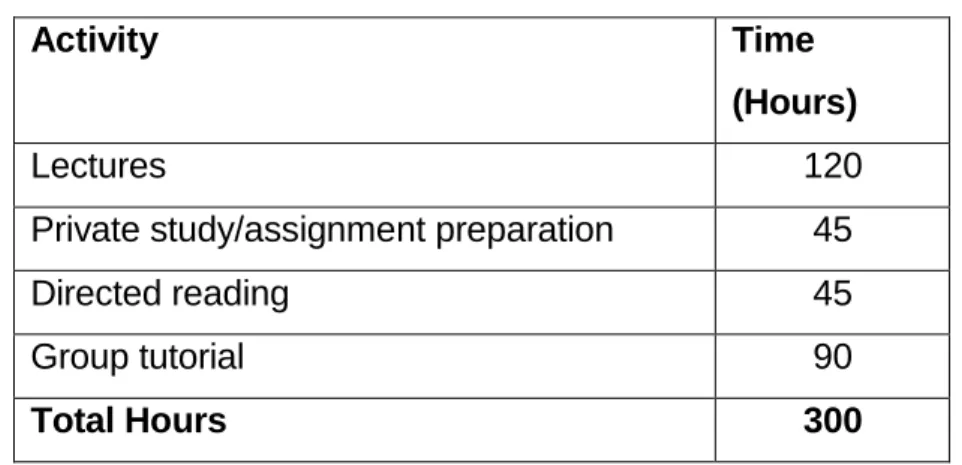

All of the core units from the programme covering theory, research, practice and personal development will form the basis for the placement work and all reflect the Standards of Proficiency listed by the Health and Care Professions Council. Each of the core units list the Doctoral learning outcomes and, as this describes, we utilise a variety of different teaching and learning styles to facilitate independent study in our students as outlined by our tables of hours and credits for each unit. The assessment activities on the taught input are designed in order that our students are fully prepared to begin their placement work and ultimately

practice as a Counselling Psychologist (SET 5.12)- all of the units for the programme can be found in the appendix.

However, the units that relate most directly to the placement are summarised below:

Therapeutic Practice 1

Wednesday and Thursday: Therapeutic placementTuesday: Skills Practice

Friday 10.00am – 12.00pm: Case Discussion

What are counselling skills

Beginning a therapeutic relationship: the referral, the assessment, contracting Building a therapeutic relationship: the core conditions

Maintain a therapeutic relationship: bond, goals, tasks, methods Ending a therapeutic relationship

13 Evaluating a therapeutic relationship

The ethical decision making process

Working in different modalities: Individual, Family and Group Therapy Innovative approaches to therapy

And in year 2:

Therapeutic Practice 2

Monday and Tuesday: Therapeutic placementThursday: Skills Practice

Friday 10.00am – 12.00pm: Case Discussion

Considering treatment plans

Integrating directive techniques into therapeutic practice Offering relaxation exercises and guided imagery

Homework activities

Working with clients different to ourselves Considering supervision

Integrating psychometrics into practice Therapeutic group work

The aims of these two units are to:

Provide a structured programme of study, which reflects upon practice at an advanced level. This will proactively support candidates’ contributions to the development of new methodologies, techniques and concepts relevant to Counselling Psychology practice and encourage individuals to produce peer reviewed research output. (Programme Aim 01)

Enhance the continuing professional and personal development across a range of contexts. Furthermore the students will contribute to the development of a range of professional competencies (theoretical understanding, research skills and therapeutic practice) in Counselling Psychology*.

(* factors directly stipulated by the HCPC and BPS) (Programme Aim 05)

The learning outcomes for these units are:

A. Knowledge & Understanding

A2. Recognise and critically evaluate ethical issues of concern to the interdisciplinary environments of Counselling Psychology practice and research

A3. Critically evaluate and creatively utilise the interdisciplinary knowledge base and complex and diverse professional environments of Counselling

Psychology practice in order to develop significant practice and research A4. Demonstrate a conceptual grasp of and ability to apply different psychological

14 B. Intellectual Skills

B1. Integrate theoretical and practice perspectives, knowledge and understanding in such a way as to generate their mutual critique and reformulation

B2. Make informed judgements on complex issues in the specialist field and be able to communicate ideas and conclusions clearly and effectively to specialist and non-specialist audiences

B3. Frame problems at the forefront of knowledge in the discipline in a fashion amenable for their investigation, discussion and communication

B4. Demonstrate originality and creativity in the practical and intellectual exploration of complex problems and solutions

C. Practical Skills

C1. Conceptualise, design and implement a project for the generation of new knowledge, applications or understanding at the forefront of the discipline, and to adjust project design in the light of peer review, evaluation, new information and unforeseen problems

C2. Conduct original research, including practice as research or other advanced scholarship which is of a quality to satisfy peer review, extend the forefront of the academic discipline and professional practice and merit publication where relevant

C3. Communicate ideas and conclusions clearly and effectively to specialist and non-specialist audiences

C4. Utilise peer review and the outcomes of collective exploration of problems to develop conceptual insights and creative skills that will support ongoing professional development

D. Transferable Skills and Personal Qualities

D1. Understand in detail the applicable techniques for original research, effective communication, and critical and independent reasoning appropriate to

advanced academic enquiry

D2. Demonstrate the qualities and transferable skills necessary for continued employment in complex and unpredictable situations, and professional, institutional or equivalent environments, including exercise of personal responsibility and largely autonomous initiative

D3. Work collaboratively in problem-solving, clarifying key concepts, designing and implementing shared research projects and communicating findings clearly and effectively to specialist and non-specialist audiences

D4. Demonstrate leadership in planning and developing on going collaborative and individual research and practice in professional settings

TheStandards of Proficiency that you will cover in this work are: The skills required for the application of practice

2a: Identification and assessment of health and social care needs. Registrant practitioner psychologists must:

15 2a.2 be able to select and use appropriate assessment techniques

2a.3 be able to undertake or arrange investigations as appropriate 2a.4 be able to analyse and critically evaluate information collected 2b: Formulation and delivery of plans and strategies for meeting health

and social care needs.

Registrant practitioner psychologists must:

2b.2 be able to draw on appropriate knowledge and skills in order to make professional judgements

2b.3 be able to formulate specific and appropriate management plans including the setting of timescales

2b.4 be able to conduct appropriate diagnostic or monitoring procedures, treatment, therapy or other actions safely and skilfully

2b.5 be able to maintain records appropriately The academic assessments for these units are:

Year 1:

Academic Unit 3: Therapeutic Practice (Research Paper 1 - Case Study - 5000 words) & completion of Documentary Evidence noted below

Year 2

Academic Unit 3: Therapeutic Practice 2 (Research Paper 2 - Process Report – 3000 words), & Case Study – 5000 words)

16

Monitoring on going fitness to practice

We are aware of the diversity of experience in terms of therapeutic work that trainees bring to the programme, ultimately the University is responsible for trainees’ client work and we need to ensure that the student has received sufficient skill and theoretical input from the University before starting their practice with you (SET 5.12). Therefore, we require that the trainee pass an initial fitness to practice review before starting to collate and count client hours, or commencing their placement.

The assessment for this is intended to be supportive and works in the following way:

From the beginning of the programme trainees will have been undertaking videoed skills session with their peers on the programme. The assessment process consists of two parts. Initially the student should present a piece of video recorded therapeutic work to the cohort as a whole. This will take place with a colleague from the programme, demonstrate person-centred therapeutic practice and be reviewed using the Person-person-centred and Experiential Psychotherapy Scale (PCEPS). Following this, all candidates will arrange a Fitness to Practise review oral assessment with a course tutor. Individuals will be asked to orally demonstrate their knowledge and understanding of professional therapeutic practice in this meeting. Each meeting will be harnessed around the Fitness to Practice documentation noted within the practice placement handbook and available on Blackboard.

The following document, (Person-centred and Experiential Psychotherapy Scale (PCEPS), will form the basis for this review:

17 Person–Centred & Experiential Psychotherapy Scale v. 10.5 (01/03/11)

Client ID______ Session ____________ Rater_________ Segment____________ Part 1: PERSON-CENTRED PROCESS Subscale

Rate the items according to how well each activity occurred during the therapy segment you’ve just listened to. It is important to attend to your overall sense of the therapist’s immediate experiencing of the client. Try to avoid forming a ‘global impression’ of the therapist early on in the session.

PC1. CLIENT FRAME OF REFERENCE/TRACK:

How much do the therapist’s responses convey an understanding of the client’s experiences as the client themselves understands or perceives it? To what extent is the therapist following the client’s track?

Do the therapist’s responses convey an understanding of the client’s inner experience or point of view immediately expressed by the client? Or conversely, do therapist’s responses add meaning based on the therapist’s own frame of reference?

Are the therapist’s responses right on client’s track? Conversely, are the therapist’s responses a diversion from the client’s own train of thoughts/feelings?

1 No tracking: Therapist’s responses convey no understanding of the client’s frame of reference; or therapist adds meaning based completely on their own frame of reference. 2 Minimal tracking: Therapist’s responses convey a poor understanding of the client’s

frame of reference; or therapist adds meaning partially based on their own frame of reference rather than the client’s.

3 Slightly tracking: Therapist’s responses come close but don’t quite reach an adequate understanding of the client’s frame of reference; therapist’s responses are slight “off” of the client’s frame or reference.

4 Adequate tracking: Therapist’s responses convey an adequate understanding of the client’s frame of reference.

5 Good tracking: Therapist’s responses convey a good understanding of the client’s frame of reference.

6 Excellent tracking: Therapists’ responses convey an accurate understanding of the client’s frame of reference and therapist adds no meaning from their own frame of reference.

PC2. CORE MEANING:

How well do the therapist’s responses reflect the core, or essence, of what the client is communicating or experiencing in the moment?

Responses are not just a reflection of surface content but show an understanding of the client’s central/core experience or meaning that is being communicated either implicitly or explicitly in the moment; responses do not take away from the core meaning of client’s communication.

1 No core meaning: Therapist’s responses address only the cognitive content or stay exclusively in the superficial narrative.

2 Minimal core meaning: Therapist’s responses address mainly the cognitive content or the superficial narrative but bring occasional glimpses into the underlying core feeling/ experience/ meaning.

3 Slight core meaning: Therapist’s responses partially but incompletely address the core meaning/feeling/ experience that underlies the client’s expressed content.

4 Adequate core meaning: Therapist’s responses were close to the core meaning/feeling/ experience that underlies the client’s expressed content, but do not quite reach it.

5 Good core meaning: Therapists’ responses accurately address the core

meaning/feeling/ experience that underlies the client’s expressed content.

6 Excellent core meaning: Therapists’ responses address with a high degree of accuracy the core meaning/feeling/ experience that underlies the client’s expressed content.

18 PC3. CLIENT FLOW:

In terms of the pacing of the client’s process, how well is the therapist responsively attuned to the client’s flow moment by moment in the session?

E.g., therapist does not interrupt client’s flow and allows reflective, self-exploratory silences; therapist does not respond too late, too seldom, or too early.

1 No attunement: Therapist is not attuned at all with the client’s pace; for example, therapist constantly interrupts clients or consistently leaves long, inappropriate silences, or therapist consistently misses opportunities to respond.

2 Minimal attunement: Therapist is not generally attuned with the client’s pace, for example often rushing the client or responding somewhat late or early.

3 Slight attunement: Therapist is inconsistently attuned with the client’s pace, sometimes responding a bit too early, or a bit too late, or not responding enough. 4 Adequate attunement: Therapist has adequate attunement with the client’s pace, for

example consistently allowing the client to finish their thoughts.

5 Good attunement: Therapist has a good attunement with the client’s pace, for example allowing reflective, self-exploratory silences.

6 Excellent attunement: Therapist is has an excellent attunement with the client’s pace, sensing the client’s need for fast or slow pacing with a high degree of accuracy and grace.

PC4. WARMTH:

How well does the therapist’s tone of voice convey appropriate warmth?

How well does the therapist’s tone of voice convey gentleness, caring, or receptiveness? 1 No warmth: Therapist is cold and aloof in their tone of voice and manner, conveys a

sense of being closed or withholding from the client.

2 Minimal warmth: Therapist conveys a bit but not nearly enough warmth

3 Inappropriate/inconsistent warmth; Therapist conveys too much

warmth/over-involvement (for example, offers inappropriate reassurance, praise or sympathy) or therapist conveys insufficient/inconsistent warmth.

4 Adequate warmth: Therapist conveys enough warmth and receptiveness.

5 Good appropriate warmth: Therapist conveys a good, facilitative level of warmth and receptiveness.

6 Excellent appropriate warmth: Therapist conveys facilitative warmth and excellent receptiveness.

PC5. CLARITY OF LANGUAGE:

How well does the therapist use language that communicates simply and clearly to the client? E.g., therapist’s responses are not too wordy, rambling, unnecessarily long; therapist does not use language that is too academic or too abstract; therapist’s responses do not get in the client’s way.

1 No clarity: Therapist’s responses are long-winded, tangled, and confusing. 2 Minimal clarity: Therapist’s responses are wordy, rambling or unfocused.

3 Slight clarity: Therapist’s responses are somewhat clear, but a bit too abstract or long. 4 Adequate clarity: Therapist’s responses are clear but a bit too long.

5 Good clarity: Therapist’s responses are clear and concise.

6 Excellent clarity: Therapist’s responses are very clear and concise, even elegantly capturing subtle client experiences in a few choice words.

19 PC6. CONTENT DIRECTIVENESS:

How much do the therapist’s responses intend to direct the client’s content?

Do the therapists’ responses introduce explicit new content? e.g., do the therapist’s responses convey explanation, interpretation, guidance, teaching, advice, reassurance or confrontation? 1 “Expert” directiveness: Therapist overtly and consistently assumes the role of expert in

directing the content of the session

2 Overt directiveness: Therapist’s responses direct client overtly towards a new content. 3 Slight directiveness: Therapist’s responses direct client clearly but tentatively towards a

new content.

4 Adequate nondirectiveness: Therapist is generally nondirective of content, with only minor, temporary lapses or slight content direction.

5 Good nondirectiveness: Therapist consistently follows the client’s lead when responding to content.

6 Excellent nondirectiveness: Therapist clearly and consistently follows the client’s lead when responding to content in a natural, inviting and unforced manner, with a high level of skill.

PC7. ACCEPTING PRESENCE:

How well does the therapist’s attitude convey an unconditional acceptance of whatever the client brings?

Does the therapist’s responses convey a grounded, centred, and acceptant presence? 1 Explicit nonacceptance: Therapist explicitly communicates disapproval or criticism of

client’s experience/ meaning/feelings.

2 Implicit nonacceptance: Therapist implicitly or indirectly communicates disapproval or criticism of client experience/meaning/feelings.

3 Incongruent/inconsistent nonacceptance: Therapist conveys anxiety, worry or

defensiveness instead of acceptance; or therapist is not consistent in the communication of acceptance.

4 Adequate acceptance: Therapist demonstrates calm and groundedness, with at least

some degree of acceptance of the client’s experience.

5 Good acceptance: Therapist conveys clear, grounded acceptance of the client’s experience; therapist does not demonstrate any kind of judgment towards client’s experience/behaviour

6 Excellent acceptance: Therapist skilfully conveys unconditional acceptance while being clearly grounded and centred in themselves, even in face of intense client vulnerability.

PC8. GENUINENESS:

How much does the therapist respond in a way that genuinely and naturally conveys their moment to moment experiencing of the client?

E.g., How much does the therapist sound phony, artificial, or overly professional, formal, stiff, pedantic or affected vs. genuine, idiosyncratic, natural or real?

1 No genuineness: Therapist sounds very fake or artificial.

2 Minimal genuineness: Therapist sounds somewhat wooden, stiff or technical. 3 Slight genuineness: Therapist sounds a bit distant or affected.

4 Adequate genuineness: Therapist sounds natural and unaffected.

5 Good genuineness: Therapist sounds very natural or genuine.

6 Excellent genuineness: Therapist sounds completely genuine, very real or idiosyncratically present, without any façade or pretence.

20 PC9. PSYCHOLOGICAL HOLDING:

How well does the therapist metaphorically hold the client when they are experiencing painful, scary, or overwhelming experiences, or when they are connecting with their vulnerabilities?

High scores refer to therapist maintaining a solid, emotional and empathic connection even when the client is in pain or overwhelmed.

Low scores refer to situations in which the therapist avoids responding or acknowledging painful, frightening or overwhelming experiences of the client.

1 No holding: Therapist oblivious to client’s need to be psychologically held: avoids responding, acknowledging or addressing client’s experience/feelings.

2 Minimal holding: Therapist seems to be aware of the client’s need to be psychologically held but is anxious or insecure when responding to client and diverts or distracts client from their vulnerability.

3 Slight holding: Therapist conveys a bit of psychological holding, but not enough and with some insecurity.

4 Adequate holding: Therapist manages to hold sufficiently the client’s experience. 5 Good holding: Therapist calmly and solidly holds the client’s experience.

6 Excellent holding: Therapist securely holds client’s experience with trust, groundedness and acceptance, even when the client is experiencing, for example, pain, fear or

overwhelmedness

PC10. DOMINANT OR OVERPOWERING PRESENCE:

To what extent does the therapist project a sense of dominance or authority in the session with the client?

Low scores refer to situations in which the therapist is taking charge of the process of the session; acts in a self-indulgent manner or takes over attention or focus for themselves; interrupting, talking over, silence or controlling the process; or acting in a definite, lecturing, or expert manner.

High scores refer to situations in which the therapist offers the client choice or autonomy in the session, allows the client space to develop their own experience, waits for the client finish their thoughts, is patient with the client, or encourages client empowerment in the session. 1 Overpowering presence: Therapist overpowers the client by strongly dominating the

interaction, controlling what the client talks about or does in the session; clearly making themselves the centre of attention; or being patronizing toward the client.

2 Controlling presence: Therapist clearly controls the client’s process of the session, acting in an expert, or dominant manner.

3 Subtle control: Therapist subtly, implicitly or indirectly controls what and how the client is in the session.

4 Noncontrolling presence: Therapist generally respects client autonomy in the session; therapist does not try to control client’s process.

5 Respectful presence: Therapist consistently respects client autonomy in the session. 6 Empowering presence: Therapist clearly and consistently promotes or validates the

21 Part 2: EXPERIENTIAL PROCESS Subscale

E1. Collaboration: How much does the therapist appropriately and skilfully work to facilitate client-therapist collaboration and mutual involvement in the goals and tasks of therapy?

How much does the therapist communicate a sense of working together or companionship in a shared effort? For example, this may include trying to locate and maintain a therapeutic focus with the client, while adapting this focus as necessary; informing the client about how therapy works or why it is important to explore feelings; also clarification and negotiation of client’s primary therapeutic goals or tasks; use of meta-communication or reference to therapeutic partnership (“we”).

1 No collaboration: therapist is authoritarian or unilateral.

2 Minimal collaboration: therapist seems to have a concept of collaboration but doesn’t implement adequately, consistently or well; therapist is either slightly controlling or generally fails to offer collaboration where appropriate.

3 Slightly collaborative: therapist is not authoritarian; however, they often act in a collaborative manner, but at times fail to do so, or do so in an awkward manner. 4 Adequate collaboration: therapist generally collaborative, with only minor, temporary

lapses or slight awkwardness.

5 Good collaboration: therapist does enough of this and does it skilfully.

6 Excellent collaboration: therapist does this consistently, skilfully, and even creatively.

E2. Experiential Specificity: How much does the therapist appropriately and skilfully work to help the client focus on, elaborate or differentiate specific, idiosyncratic or personal

experiences or memories, as opposed to abstractions or generalities?

E.g., By reflecting specific client experiences using crisp, precise, differentiated and

appropriately empathic reflections; or asking for examples or to specify feelings, meanings, memories or other personal experiences.

1 No specificity: therapist consistently responds in a highly abstract, vague or intellectual manner.

2 Minimal specificity: therapist seems to have a concept of specificity but doesn’t

implement adequately, consistently or well; therapist is either somewhat vague or abstract or generally fails to encourage experiential specificity where appropriate.

3 Slight specificity: therapist is often or repeatedly vague or abstract; therapist only slightly or occasionally encourages experiential specificity; sometimes responds in a way that points to experiential specificity, at times they fail to do so, or do so in an awkward manner.

4 Adequate specificity: where appropriate, therapist generally encourages client experiential specificity, with only minor, temporary lapses or slight awkwardness. 5 Good specificity: therapist does enough of this and does it skilfully, where appropriate

trying to help the client to elaborate and specify particular experiences.

6 Excellent specificity: therapist does this consistently, skilfully, and even creatively, where appropriate, offering the client crisp, precise reflections or questions.

22 E3. Emotion Focus: How much does the therapist actively work to help the client focus on and actively articulate their emotional experiences and meanings, both explicit and implicit?

E.g., By helping clients focus their attention inwards; by focusing the client’s attention on bodily

sensations; by reflecting toward emotionally poignant content, by inquiring about client feelings, helping client intensify, heighten or deepen their emotions, by helping clients find ways of describing emotions; or by making empathic conjectures about feelings that have not yet been expressed. Lower scores reflect ignoring implicit or explicit emotions; staying with non-emotional content; focusing on or reflecting generalized emotional states (“feeling bad”) or minimizing emotional states (e.g., reflecting “angry” as “annoyed”).

1 No emotion focus: therapist consistently ignores emotions or responds instead in a highly intellectual manner while focusing entirely on non-emotional content. When the client expresses emotions, the therapist consistently deflects the client away from them. 2 Minimal emotion focus: therapist seems to have a concept of emotion focus but doesn’t

implement adequately, consistently or well; therapist may generally stay with non-emotional content; sometimes deflects client way from their emotion; reflects only general emotional states (“bad”) or minimizes client emotion.

3 Slight emotion focus: therapist often or repeatedly ignores or deflects client away from emotion; therapist only slightly or occasionally helps client to focus on emotion; while they sometimes respond in a way that points to client emotions, at times they fail to do so, or do so in an awkward manner.

4 Adequate emotion focus: where appropriate, therapist generally encourages client focus on emotions (by either reflections or other responses), with only minor, temporary lapses or slight awkwardness.

5 Good emotion focus: therapist does enough of this and does it skilfully, where appropriate trying to help the client to evoke, deepen and express particular emotions.

6 Excellent emotion focus: therapist does this consistently, skilfully, and even creatively, where appropriate, offering the client powerful, evocative reflections or questions, while at the same time enabling the client to feel safe while doing so.

E4. Client Self-development: How much does the therapist actively work to facilitate client new awareness, growth, self-determination or empowerment?

Does the therapist reflect toward, support, or symbolize emerging new aspects of client emotions or other experiences? E.g., This may include offering the client choices; by reflecting/emphasizing client agency, focusing on the client’s emerging sense of inner strength or emerging new client changes or insights or ways of experiencing self or others; or accurately reflecting the longing for change in client despair without dismissing the client’s pain. Lower ratings are used when the therapist ignores new awareness, insight or shifts, or focuses on client despair or stuckness.

1 No client self-development: therapist consistently ignores client new awareness, agency or emerging changes, or generally responds instead to client despair or stuckness. When the client expresses new, emerging experiences, the therapist consistently deflects the client away from them.

2 Minimal client self-development: therapist has the concept of client self-development focus but doesn’t implement it adequately, consistently or well; therapist generally stays with old or stuck content; or often deflects client away from new experience or agency.

3 Slight client self-development: therapist often or repeatedly deflects client away from emerging new experiences or agency; therapist only slightly facilitates client self-development; while they sometimes respond in a way that points to client self-development, at times they fail to do so, or do so in an awkward manner.

4 Adequate client self-development: where appropriate, therapist generally encourages focus on emerging client experiences or agency (by either reflections or other responses), with only minor, temporary lapses or slight awkwardness.

5 Good client self-development: therapist does enough of this and does it skilfully, where appropriate trying to help the client to focus on emerging new experiences or agency, perhaps by offering client choices or implicitly or explicitly communicating trust in the client’s process. 6 Excellent client self-development: therapist does this consistently, skilfully, and even

creatively, where appropriate; for example, offering responses that accurately identify client hope in the midst of despair or implicitly convey trust in the client’s self-development potential.

23 E5. Emotion Regulation Sensitivity: How much does the therapist actively work to help the client adjust and maintain their level of emotional arousal for productive self-exploration?

Client agency is central; this is not imposed by the therapist. There are three possible situations:

(a) If the client is overwhelmed by feelings and wants help in moderating them, does the therapist try to help the client to manage these emotions? E.g., By offering a calming and holding presence; by using containing imagery; or by helping the client self-soothe vs. allowing the client to continue to panic or feel overwhelmed or unsafe.

(b) If the client is out of touch with their feelings and wants help in accessing them, does the therapist try to help them appropriately increase emotional contact? E.g., by helping them review current concerns and focus on the most important or poignant; by helping them remember and explore memories of emotional experiences; by using vivid imagery or language to promote feelings vs. enhancing distance from emotions.

(c) If the client is at an optimal level of emotional arousal for exploration, does the therapist try to help them continue working at this level, rather than deepening or flattening their

emotions?)

1 No facilitation: therapist consistently ignores issues of client emotional regulation, or generally works against client emotional regulation, i.e., allowing client to continue feel overwhelmed or distanced.

2 Minimal facilitation: therapist seems to have a concept of facilitating client emotional regulation but doesn’t implement adequately, consistently or well; therapist either generally ignores the client’s desire to contain overwhelmed emotion or to approach distanced emotion; sometimes they misdirect the client out of a productive, optimal level of emotional arousal, into either stuck or overwhelmed emotion or emotional distance or avoidance.

3 Slight facilitation: therapist often or repeatedly ignores or deflects client away from their desired level of emotional regulation productive for self-exploration; therapist only slightly facilitates productive self-exploration. While they sometimes respond in a way that facilitates client productive emotional regulation, at times they fail to do so, or do so in an awkward manner.

4 Adequate facilitation: Where appropriate, therapist generally encourages client emotional regulation (e.g., by helping them approach difficult emotions or contain excessive emotional distress as desired by client), with only minor, temporary lapses or slight awkwardness.

5 Good facilitation: therapist does enough emotional regulation facilitation and does it skilfully and in accordance with client’s desires, where appropriate trying to help the client to maintain a productive level of emotional arousal.

6 Excellent facilitation: therapist does this consistently, skilfully, and even creatively, where desired, offering the client evocative or focusing responses to help the client approach difficult emotions when they are too distant and to contain overwhelming emotions, all within a safe, holding environment.

24 Doctorate in Counselling Psychology: Practice Review

Sections A – D to be completed by the personal tutor following a tutor led seminar Section E to be completed by the trainee after discussion with the personal tutor of Sections C and D

Section F to be signed by both tutor and trainee on completion of all earlier sections Section A: Trainee details

Trainees Name:

Personal Tutor’s Name:

Section B: Initial Practice Review Details Date:

The student has completed an initial review of their therapeutic work. This has consisted of the following:

1. The student has produced a video recording of them working as a therapist for a colleague on the programme (acting in the role of client). This meeting must last a minimum of 30 minutes.

2. The student has reviewed and processed a minimum of a 15 minute segment of this video in a tutor led seminar. This will reflect upon the therapeutic alliance between therapist and client, skills development, professional/personal development and research awareness (i.e. considering how their work might be evaluated as part of an empirical research project). 3. Following the tutor led seminar the trainee will meet up individually with the tutor to discuss the formal assessment of this work and their future progression onto placement.

Section C: Evaluation of Competence

In the sections below please assess the trainee’s competence in the following dimensions: (1) their awareness and understanding of the context of their placement, (2) their therapeutic sensitivity in practice, and (3) the personal qualities that they bring to their role as a therapist. Each Practice Placement Learning Outcome is reviewed using the University’s Doctoral Level assessment criteria* and therefore in their videoed work the trainee should:

Display the capacity to pursue research and scholarship

Produce an original contribution and substantial addition to knowledge

Demonstrate the professional location and relevance of their placement activities and its potential outcomes

Demonstrate rigorous and critical thinking in regard to the literature and theory

Demonstrate how the topic of their placement activities is related to a wider field of knowledge and research

Demonstrate an understanding of the design and conduct of empirical research Demonstrate appropriate therapeutic knowledge, understanding and skills

25 Demonstrate the capacity to self reflect in a way appropriate to the work of a Counselling Psychologist Demonstrate the awareness of philosophical, ethical, legal and professional issues

Demonstrate therapeutic sensitivity within their work as a Counselling Psychologist

These criteria must be considered when reflecting upon the trainee’s progress. You will also be asked to confirm whether the student has met these standards or not at the end of this document.

Each of the aforementioned dimensions of practice is divided up into key areas related to their development as a Counselling Psychologist and associated Learning Outcomes at the University. In relation to each area please indicate whether the trainee has satisfactorily demonstrated these core components of their learning activities within their videoed work. We ask you to indicate this by deleting the irrelevant term (i.e. delete ‘not demonstrated’ where a trainee has demonstrated that particular assessment criteria). Following this we invite you to comment more qualitatively regarding their progress**.

*These have been amended slightly for use in placement settings.

**Please note that the qualitative comments will be used as formative information for the trainee’s development whilst the objective components will be used to assess progression on the programme. Students will be expected to demonstrate all Practice Placement Learning Outcomes listed below.

1 Context of Counselling Psychology Placement

Knowledge and understanding of ethical concerns related to practice in different counselling psychology settings (A2):

The student has demonstrated rigorous and critical knowledge of: the HCPC standards of conduct, performance and ethics in relation to the context of their work

D/ND the BPS codes of ethics in relation to the context of their work D/ND obtaining informed consent from the client in the context of their

counselling psychology practice

D/ND

D = Demonstrated, ND = Not demonstrated (Please delete as appropriate) Qualitative comments if applicable:

2 Counselling Psychology Practice

Demonstrate a sound grasp and application of different psychological theories to expand knowledge and understanding of practice (A4) in order to make informed judgements (B2). The student has demonstrated rigorous and critical knowledge of:

psychological theory to inform client assessment procedures D/ND psychological theory to devise appropriate therapeutic goals D/ND psychological theory to devise appropriate therapeutic tasks D/ND

26 psychological theory to inform formulation within client work D/ND

psychological theory to support the develop an appropriate therapeutic bond

D/ND psychological theory to understand potential ruptures in the

therapeutic alliance

D/ND

D = Demonstrated, ND = Not demonstrated (Please delete as appropriate) Communicate clearly to specialist and non specialist audiences (C3)

The student has demonstrated scholarly research and practical skills to: communicate clearly to their colleagues and other professionals that they encounter in their work as a trainee Counselling Psychologist

D/ND

D = Demonstrated, ND = Not demonstrated (Please delete as appropriate) Integrate theoretical and practice perspectives in order to generate new ways or working informed by theory (B1), in an original and creative way (B4)

The student has demonstrated the capacity for original thought and intellectual skill to: integrate psychological theory in order to support the creation of a

Therapeutic Alliance

D/ND integrate psychological theory in order to apply a variety of

therapeutic techniques that creatively respond to the presenting issues that clients bring to therapy

D/ND

creatively integrate the philosophical, theoretical and artistic underpinnings of Counselling Psychology to inform practice

D/ND

D = Demonstrated, ND = Not demonstrated (Please delete as appropriate) Qualitative comments if applicable:

3 Personal Qualities

Demonstrate the qualities and transferable skills necessary to work in the complex and often unpredictable environment of counselling psychology (D2)

The student has the personal and professional qualities to:

respond flexibly in relation to work directly with clients D/ND

D = Demonstrated, ND = Not demonstrated (Please delete as appropriate) Demonstrate personal responsibility and autonomy in working in the field of counselling psychology (D2)

The student has the personal and professional qualities to:

make informed decisions in relation to their profession role D/ND to work professionally in an independent manner D/ND to understand the limits of their knowledge and skills base and

consult with colleagues as appropriate

27 D = Demonstrated, ND = Not demonstrated (Please delete as appropriate) Qualitative comments if applicable:

Section D: Overall Evaluation (please comment below)

Please indicate whether you feel the trainee has completed this initial review activity in line with the Doctoral Level assessment criteria.

Display the capacity to pursue research and scholarship. D / ND Produce an original contribution and substantial addition to knowledge. D / ND Demonstrate the professional location and relevance of their placement

activities and its potential outcomes.

D / ND Demonstrate rigorous and critical thinking in regard to the literature

and theory.

D / ND Demonstrate how the topic of their placement activities is related to a

wider field of knowledge and research.

D / ND Demonstrate an understanding of the design and conduct of empirical

research.

D / ND Demonstrate appropriate therapeutic knowledge, understanding and

skills

D / ND Demonstrate the capacity to self reflect in a way appropriate to the

work of a Counselling Psychologist

D / ND Demonstrate the awareness of philosophical, ethical, legal and

professional issues

D / ND Demonstrate therapeutic sensitivity within their work as a Counselling

Psychologist

D / ND

Additional comments:

Do you have any concerns about the student’s fitness to practice? Yes/ No

Additional comments if necessary:

Section E: trainee’s comments on the evaluation (please comment below)

Section F: Confirmation and Signatures Trainee’s confirmation