Primary Health Care Providers’ Advice for a Dental

Checkup and Dental Use in Children

WHAT’S KNOWN ON THIS SUBJECT: Dental care is the greatest unmet health care need for children. Medical and dental professionals agree that physicians have an important role in increasing children’s use of dental care. However, evidence for the effectiveness of a physician dental referral is poor.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS: No previous study has examined the relationship between a health care provider’s recommendation and dental use among a nationally representative sample of children. This study estimates the association between a child being advised to see the dentist and having a dental visit.

abstract

OBJECTIVE:In this study we estimated factors associated with chil-dren being advised to see the dentist by a doctor or other health provider; tested for an association between the advisement on the likelihood that the child would visit the dentist; and estimated the effect of the advisement on dental costs.

METHODS:We identified a sample of 5268 children aged 2 to 11 years in the 2004 Medical Expenditures Panel Survey. A cross-sectional analysis with logistic regression models was conducted to estimate the likeli-hood of the child receiving a recommendation for a dental checkup, and to determine its effect on the likelihood of having a dental visit. Differences in cost for children who received a recommendation were assessed by using a linear regression model. All analyses were con-ducted separately on children aged 2 to 5 (n⫽2031) and aged 6 to 11 (n⫽3237) years.

RESULTS:Forty-seven percent of 2- to 5-year-olds and 37% of 6- to 11-year-olds had been advised to see the dentist. Children aged 2 to 5 who received a recommendation were more likely to have a dental visit (odds ratio: 2.89 [95% confidence interval: 2.16 –3.87]), but no differ-ence was observed among older children. Advice had no effect on dental costs in either age group.

CONCLUSIONS:Health providers’ recommendation that pediatric pa-tients visit the dentist was associated with an increase in dental visits among young children. Providers have the potential to play an impor-tant role in establishing a dental home for children at an early age. Future research should examine potential interventions to increase effective dental referrals by health providers. Pediatrics 2010;126: e435–e441

AUTHORS:Heather A. Beil, MPH and R. Gary Rozier, DDS, MPH

Department of Health Policy and Management, Gillings School of Global Public Health, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, North Carolina

KEY WORDS

oral health, access to dental care, MEPS

ABBREVIATIONS

MEPS—Medical Expenditure Panel Survey MSA—metropolitan statistical area

CSHCN— children with special health care needs OR— odds ratio

CI— confidence interval

www.pediatrics.org/cgi/doi/10.1542/peds.2009-2311

doi:10.1542/peds.2009-2311

Accepted for publication May 11, 2010

Address correspondence to Heather A. Beil, MPH, Department of Health Policy and Management, UNC Chapel Hill Gillings School of Global Public Health, CB 7411, Chapel Hill, NC 27599. E-mail: hbeil@email.unc.edu

PEDIATRICS (ISSN Numbers: Print, 0031-4005; Online, 1098-4275).

Copyright © 2010 by the American Academy of Pediatrics

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE:The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

tal care is the greatest unmet health care need among children.1,2

Approxi-mately 80% of children experience dental caries by the age of 17.3Medical

and dental professionals agree that physicians have an important role in increasing children’s use of dental care and promoting oral health.4–7

Be-fore 2008, the American Academy of Pediatrics recommended that physi-cians advise all children to see the den-tist by the age of 3 and for children at high risk to see the dentist by the age of 1.5Early dental visits also have been

promoted by other medical profes-sional organizations.8However, the

ef-fectiveness of a health provider’s rec-ommendation to see the dentist remains unknown.

A recent study revealed that approxi-mately half of US children were ad-vised to see a dentist by a health pro-vider.9 A systematic review by the US

Preventive Services Task Force re-vealed that evidence for the effective-ness of physician dental referral is poor, primarily because of the small number of studies and their poor qual-ity.10It is important to know whether a

health provider’s recommendation is effective in increasing the use of den-tal care because young children are more likely to visit a medical office than a dental office. There has been no previous study to our knowledge in which the relationship between a health care provider’s recommenda-tion and dental use was examined among a nationally representative sample of children.

In this study we addressed 3 aims. We estimated the factors associated with children being advised by a health pro-vider to have a dental checkup and the association between being advised to see the dentist and having a dental visit. Children who were advised to see the dentist may have had greater

den-timated differences in the amount of dental expenditures for children who were or were not advised to see the dentist among those who had a dental visit.

METHODS

Data Source

The Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) is a nationally representative set of surveys that includes informa-tion on health care costs, use and in-surance coverage developed by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. In this study, we use informa-tion from the 2004 survey, which had a total sample size of 13 018 households representing 32 707 civilian, noninsti-tutionalized individuals. Our sample in-cluded children aged 2 to 11 years old and their dental use during 2004. We excluded adolescents because of their low rates of use of preventive medical services and small number of opportu-nities to receive a dental recommenda-tion.11We also excluded children in

fos-ter care because of differences in determinants of their use of dental and medical care.

A total of 5547 children were eligible for this study. Of these children,⬃5% were missing data and were excluded from the analysis. The final sample size was 5268 children, and all analyses were conducted separately on 2- to 5-year-olds (n ⫽ 2031) and 6- to 11-year-olds (n⫽3237) because of differ-ences in their medical and dental use and oral health risks. Parents were sent materials to record information about the child’s use of health ser-vices. They were then interviewed via telephone using computer-assisted personal interviewing. Previously pub-lished reports have provided detailed information about MEPS methodology and data-collection procedures.12

the 3 study aims: (1) whether the child was advised to see the dentist within the previous year; (2) whether the child had a dental visit in 2004; and (3) total dental expenditures.

Receipt of advice about a dental visit was assessed by asking the parents whether a doctor or other health care provider had ever advised a dental checkup. A health provider was de-fined for the respondent as a general doctor, a specialist doctor, a nurse practitioner, a physician assistant, a nurse, or anyone else the child would see for health care, and the question was asked within a series of questions on preventive health care that the child received during visits to the doctor or other health provider. If the parents reported receiving a recommendation, they were asked whether it was within the previous year, within the previous 2 years, or⬎2 years ago. We created 3 binary variables to indicate whether the child had been advised to go to the dentist within the previous year, the previous 2 or more years, or never. We categorized recommendations within the previous year separately, because a more recent recommendation is im-portant for timely follow-up care at the dentist.

A binary variable that indicated whether the child had a dental visit in 2004 was the dependent variable to as-sess the association between a recom-mendation and dental use. Dental vis-its included care of any type provided by general dentists, dental hygienists, and all dental specialists.

child received at each dental visit and the associated expenditures, including the source of payment and amount, and they were asked to provide docu-mentation such as a bill or receipt, if available.

Independent Variables

For the second and third aims, the

main independent variable was

whether the child had been advised to see a dentist as defined above. By us-ing the Andersen13 behavioral model

for health care service use as a guide (Fig 1), we controlled for potential child and family characteristics that could affect dental and medical use. On the basis of previous research in den-tal and health services use, we hypoth-esized that the child’s dental use would be influenced by child-predisposing characteristics (age, race, ethnicity, special health care need, health tus, and residing in a metropolitan sta-tistical area [MSA] and US geographic region of residence)2,14–16 and

child-and family-enabling characteristics (family income as a percentage of pov-erty, parent’s education, whether the child had a regular source of medical care, whether the parent was a regu-lar user of dental care, and medical and dental insurance coverage).2,17–20

We identified parents who reported us-ing dental care at least once per year as a “regular user” of dental care.

Hav-ing a regular source of medical care was determined in the MEPS by asking if there was a particular doctor’s of-fice, clinic, health center, or other place that the parent takes the child if he or she is sick or needs advice about his or her health. We created 4 binary variables to capture the child’s medi-cal and dental health insurance status: private health insurance with dental coverage; private health insurance without dental coverage; public insur-ance (included Medicaid, Child Health Insurance Program, or other public in-surance); and neither medical nor dental insurance. We created a binary variable to indicate children with spe-cial health care needs (CSHCN), deter-mined in the MEPS by using the 5-item, validated CSHCN screening question-naire based on the Maternal and Child Health Bureau definition of CSHCN.21,22

In our sample of CSHCN, we did not in-clude children who were identified as CSHCN only because they took a regu-lar medication because of reasons de-scribed in a previous article.16

Analyses

Bivariate and logistic regression was used to estimate the relationship be-tween a child being advised to see the dentist within the previous year and associated factors. We used a sepa-rate logistic regression model to esti-mate the likelihood of having a dental

visit in 2004. We tested for differences in the amount of total dental expendi-tures by using multivariate regression

analyses among children who had a dental visit. The analyses were com-pleted in Stata 10 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX), and estimates were

cor-rected for the complex survey design by using Stata survey procedures. All tests used a significance level of .05.

RESULTS

Sample Characteristics

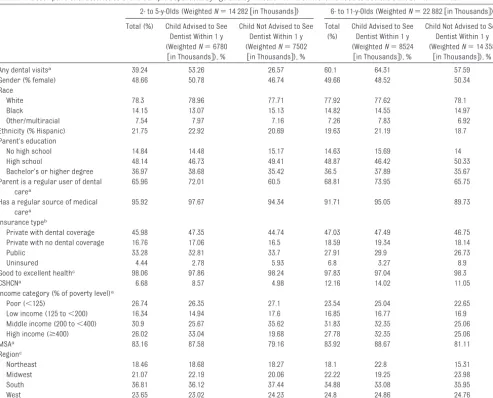

In this national sample, 47% of 2- to 5-year-olds and 37% of 6- to 11-year-olds had been advised to have a dental

checkup by a health provider within the previous year, and 39% of 2- to 5-year-olds and 60% of 6- to 11-year-olds had at least 1 dental visit in 2004.

Several differences were found be-tween children who had been advised to see the dentist within the previous year and other children in the

bivari-ate analysis (Table 1).

Likelihood of Being Advised to See the Dentist in the Previous Year Among both age groups, children

whose parents were regular users of dental care were more likely to have been advised to see the dentist in the previous year (2- to 5-year-olds: odds

ratio [OR]: 1.60 [95% confidence inter-val (CI): 1.21–2.11]) (6- to 11-year-olds: OR: 1.37 [95% CI: 1.05–1.79]) (Table 2). Likewise, children who had a regular

source of medical care were more likely to be advised to see a dentist among both 2- to 5-year-olds (OR: 2.07 [95% CI: 1.16 –3.07]) and 6- to

11-year-olds (OR: 1.78 [95% CI: 1.15–2.76]). Chil-dren living in an MSA in both age groups were more likely to be advised to see the dentist than other children, and children aged 2 to 5 from

low-income families were less likely to re-ceive a recommendation.

Predisposing characteristics Child’s age, race/ethnicity, and

health status Geographic location

Enabling resources Family income, parent’s education, child had a regular source of medical care, parent was

a regular user of dental care, and medical and dental insurance

coverage

Outcome 1: Advised to see the dentist

Outcome 2: Had a dental

visit

Outcome 3: Total dental expenditures

FIGURE 1

Determinants of dental-care use conceptual model (based on the Andersen model13).

Likelihood of Having a Dental Visit Children in both age groups who had been advised to have a dental checkup within the previous year were more likely to see a dentist than other chil-dren in the bivariate analyses (Table 1). However, in the multivariate analy-sis, only children in the 2- to 5-year-old age group who received a recommen-dation were more likely to have a den-tal visit than were children who did not (OR: 2.89 [95% CI: 2.16 –3.87]) (Table 2). Children who were advised to see the dentist within 2 or more years were no more likely to see a dentist than were children who had never been advised

among both age groups. Children in both age groups whose parents were a regular user of dental care had a greater likelihood of having a dental visit than were other children (2- to 5-year-olds: OR: 1.65 [95% CI: 1.23– 2.22]) (6- to 11-year-olds: OR: 2.76 [95% CI: 2.14 –3.56]).

Amount of Dental Expenditures Among children aged 2 to 5 who had a dental visit, those who were advised to see the dentist within the previous year had an average of $187 in total dental expenditures compared with $204 for children who had not been

ad-vised to do so. Children aged 6 to 11 who had been advised to visit a dentist had $504 in total dental expenditures per person compared with $397 per person for other children. No statisti-cally significant differences in the amount of total dental expenditures for children who had and had not been advised to see the dentist were found among either age group (regression results not shown).

DISCUSSION

Approximately 47% of children aged 2 to 5 years were advised to see the den-tist in the previous year, and those who Total (%) Child Advised to See

Dentist Within 1 y (WeightedN⫽6780

关in Thousands兴), %

Child Not Advised to See Dentist Within 1 y (WeightedN⫽7502

关in Thousands兴), %

Total (%)

Child Advised to See Dentist Within 1 y (WeightedN⫽8524

关in Thousands兴), %

Child Not Advised to See Dentist Within 1 y (WeightedN⫽14 358

关in Thousands兴), %

Any dental visitsa 39.24 53.26 26.57 60.1 64.31 57.59

Gender (% female) 48.66 50.78 46.74 49.66 48.52 50.34

Race

White 78.3 78.96 77.71 77.92 77.62 78.1

Black 14.15 13.07 15.13 14.82 14.55 14.97

Other/multiracial 7.54 7.97 7.16 7.26 7.83 6.92

Ethnicity (% Hispanic) 21.75 22.92 20.69 19.63 21.19 18.7

Parent’s education

No high school 14.84 14.48 15.17 14.63 15.69 14

High school 48.14 46.73 49.41 48.87 46.42 50.33

Bachelor’s or higher degree 36.97 38.68 35.42 36.5 37.89 35.67

Parent is a regular user of dental carea

65.96 72.01 60.5 68.81 73.95 65.75

Has a regular source of medical carea

95.92 97.67 94.34 91.71 95.05 89.73

Insurance typeb

Private with dental coverage 45.98 47.35 44.74 47.03 47.49 46.75

Private with no dental coverage 16.76 17.06 16.5 18.59 19.34 18.14

Public 33.28 32.81 33.7 27.91 29.9 26.73

Uninsured 4.44 2.78 5.93 6.8 3.27 8.9

Good to excellent healthc 98.06 97.86 98.24 97.83 97.04 98.3

CSHCNa 6.68 8.57 4.98 12.16 14.02 11.05

Income category (% of poverty level)a

Poor (⬍125) 26.74 26.35 27.1 23.54 25.04 22.65

Low income (125 to⬍200) 16.34 14.94 17.6 16.85 16.77 16.9

Middle income (200 to⬍400) 30.9 25.67 35.62 31.83 32.35 25.06

High income (ⱖ400) 26.02 33.04 19.68 27.78 32.35 25.06

MSAa 83.16 87.58 79.16 83.92 88.67 81.11

Regionc

Northeast 18.46 18.68 18.27 18.1 22.8 15.31

Midwest 21.07 22.19 20.06 22.22 19.25 23.98

South 36.81 36.12 37.44 34.88 33.08 35.95

West 23.65 23.02 24.23 24.8 24.86 24.76

aStatistically significant at the 1% level for both age groups. bStatistically significant at the 5% level for both age groups.

received a recommendation were al-most 3 times more likely to have a den-tal visit than were children who did not receive a recommendation. Children aged 6 to 11 years who were advised to see a dentist in the previous year were no more likely to see a dentist than were those who were not advised. Young children were more likely to see a medical provider than were older children; however, young children were less likely to see a dentist. More-over, older children were more likely to have a regular dentist, thereby re-ducing the need for a recommendation from the health provider. Therefore, younger children could be expected to

have more opportunity to receive a recommendation to see the dentist, and the recommendation has the

po-tential to be more effective because they may be less likely to visit the den-tist in the absence of a recommenda-tion. These findings suggest that

health care providers can play an important role in ensuring that preschool-aged children establish a dental home at an early age and obtain

dental care.

The strongest predictor of whether a child was advised to see the dentist

was whether the child had a regular source of medical care. In addition,

children who had parents who were regular users of dental care were also more likely to be advised to see the dentist. Parents who are regular users of dental care may generate a recom-mendation by asking if the child should see the dentist. Children living in an MSA were also more likely to be ad-vised to see the dentist than were other children. The supply of dentists is likely greater in an MSA; thus health providers may be more likely to make a recommendation because they are more likely to have established rela-tionships with dentists or they believe that parents will be able to locate a dentist for the child on their own. Chil-TABLE 2 Likelihood of Being Advised to See the Dentist Within 1 Year and Likelihood of Having Any Dental Visit for 2- to 5-Year-Old and 6- to 11-Year-Old

Children

2- to 5-y-Olds Weighted (N⫽14 282关in Thousands兴)

6- to 11-y-Olds Weighted (N⫽22 882关in Thousands兴)

Advised to See Dentist Within 1 y OR (95% CI)

Dental Visit OR (95% CI)

Advised to See Dentist Within 1 y OR (95% CI)

Dental Visit OR (95% CI)

Child advised to see a dentist within 1 y — 2.89 (2.16–3.87) — 1.13 (0.90–1.42)

Child advised to see a dentist withinⱖ2 y — 1.48 (0.85–2.60) — 0.84 (0.60–1.19)

Child never advised to see a dentist (reference) — — — —

Gender (female) 1.26 (1.01–1.58) 1.20 (0.93–1.54) 0.96 (0.79–1.16) 1.02 (0.85–1.22)

Parent’s education

No high school 1.14 (0.75–1.74) 0.56 (0.37–0.85) 1.18 (0.82–1.70) 0.37 (0.25–0.54)

High school 1.20 (0.88–1.64) 0.80 (0.60–1.07) 1.00 (0.75–1.34) 0.61 (0.43–0.85)

Bachelor’s or higher degree (reference) — — — —

Parent is a regular user of dental care 1.60 (1.21–2.11) 1.65 (1.23–2.22) 1.37 (1.05–1.79) 2.76 (2.14–3.56) Race

White (reference) — — — —

Black 0.91 (0.63–1.31) 0.80 (0.52–1.25) 0.97 (0.70–1.35) 0.53 (0.39–0.73)

Other/multiracial 1.22 (0.77–1.94) 1.06 (0.68–1.66) 1.08 (0.70–1.67) 0.77 (0.48–1.24)

Hispanic 1.26 (0.91–1.74) 0.98 (0.69–1.40) 1.19 (0.89–1.60) 0.66 (0.49–0.89)

Income category (% of poverty level)

Poor (⬍125) 0.60 (0.36–1.00) 0.51 (0.32–0.82) 0.94 (0.63–1.39) 0.64 (0.42–0.99)

Low income (125 to⬍200) 0.52 (0.32–0.82) 0.49 (0.31–0.78) 0.84 (0.58–1.22) 0.62 (0.41–0.94) Middle income (200 to⬍400) 0.43 (0.30–0.62) 0.50 (0.34–0.75) 0.61 (0.45–0.84) 0.82 (0.60–1.14)

High income (⬎400) (reference) — — — —

Has a regular source of medical care 2.07 (1.16–3.70) 1.01 (0.56–1.80) 1.78 (1.15–2.76) 1.32 (0.83–2.10) Insurance type

Private with dental coverage (reference) — — — —

Private with no dental coverage 1.06 (0.74–1.53) 1.21 (0.80–1.80) 1.08 (0.79–1.48) 0.89 (0.65–1.22)

Public 1.11 (0.76–1.62) 1.19 (0.80–1.77) 1.08 (0.80–1.45) 1.18 (0.87–1.59)

Uninsured 0.56 (0.30–1.06) 0.65 (0.33–1.31) 0.43 (0.28–0.65) 0.38 (0.24–0.60)

Good to excellent health 1.10 (0.51–2.38) 0.95 (0.43–2.13) 0.59 (0.36–0.97) 0.72 (0.40–1.30)

CSHCN 1.96 (1.24–3.08) 1.43 (0.90–2.27) 1.23 (0.91–1.67) 0.74 (0.56–0.98)

MSA 1.81 (1.31–2.50) 1.09 (0.75–1.59) 1.73 (1.26–2.37) 1.61 (1.13–2.29)

Region

Northeast 0.81 (0.53–1.23) 0.99 (0.68–1.44) 1.38 (1.01–1.90) 1.04 (0.69–1.56)

Midwest 1.15 (0.82–1.62) 1.21 (0.82–1.80) 0.88 (0.62–1.23) 1.41 (1.01–1.97)

South (reference) — — — —

West 0.94 (0.62–1.43) 1.19 (0.81–1.76) 0.98 (0.72–1.34) 1.33 (1.00–1.77)

to see the dentist than were children of high-income parents. Children in lower-income families may be less likely to have seen a health provider and, therefore, would have less oppor-tunity to receive a dental recommen-dation. Health providers may also be assuming that children of lower-income parents would not be able to follow through with the recommenda-tion to see a dentist and, thus, are not advising a dental checkup. Given the disparities in access to dental care among low-income children, health providers should be encouraged to ad-vise dental visits to children of lower-income parents.

At the time this study was conducted, the American Academy of Pediatrics recommended that physicians and other health providers advise all chil-dren to see the dentist by the age of 3 and children at high risk to see the dentist by the age of 1.5Because of the

increasing prevalence of early child-hood caries among preschool-aged children and the effectiveness of inter-ventions such as fluoride varnish to prevent caries in young children, pro-fessional guidelines now recommend that all children be referred to the den-tist by 1 year of age when there is an adequate supply of dentists.23–25 The

findings in this study suggest that studies are warranted to identify strat-egies to increase the rate at which health providers recommend a dental checkup.

Interventions such as guidelines and checklists are effective in improving referral rates from primary care to secondary care.26However, physicians

face a number of barriers when refer-ring young children to the dentist.6

Physicians can have limited knowledge of oral health–related issues,6 which

may inhibit a physician’s willingness or ability to appropriately advise that a

referring subgroups of patients such as those with Medicaid or are unin-sured, particularly when the supply of

dentists is limited.6If the medical

pro-vider is unable to identify a dentist to whom to refer the child, they may be unwilling to advise the parent to take the child in for a dental checkup.

Multifaceted interventions that culti-vate partnerships between medical and dental providers and provide edu-cational training to medical providers on oral health and on the importance and timing of recommending a dental

checkup may increase recommenda-tion rates for dental visits. Collabora-tions could facilitate identification of dentists who provide dental care for young children, which would be helpful in both making targeted recommenda-tions and developing a list of providers to share with parents. Future studies

are warranted that examine the rela-tionship between medical provider recommendations and dental use while controlling for the supply of den-tal providers, as well as intervention studies to educate health providers and establish collaborations between medical and dental providers.

Among both child age groups, having a parent who was a regular user of den-tal care significantly increased the likelihood that the child would visit the

dentist. Other recent studies have also found a link between parent and child dental health and use.19,27–31However, 1

study found that only 38% of low-income parents had a regular source of dental care.19These findings

empha-size the need to target parents in ef-forts to improve access to dental care for children, particularly for

low-income children. If parents can be ed-ucated on their own need for regular dental care and access to dental care can be expanded to parents, then the

There are several limitations to this study. This study might have suffered from selection bias, because children who were advised to see the dentist by a health provider may have been more likely to be users of the health care system. We minimized this potential bias by controlling for the child having a regular source of medical care and having a parent who was a regular user of dental care.

We did not have a measure of the child’s disease status. Studies have re-vealed that physicians can identify a child’s dental disease status accu-rately and are more likely to refer chil-dren with disease than those without or with elevated risk but no disease.4,32

However, children who were advised within the previous year did not differ from other children in the amount of total dental expenditures.

The study was based on self-reported measures and, thus, is subject to re-porting bias. Estimates for dental vis-its and expenditures were not verified with providers like the medical data were. In addition, the study is cross-sectional, so we cannot establish a causal relationship. Nonetheless, the study is the first, to our knowledge, to have examined the correlation be-tween a recommendation to see a den-tist by a health provider and dental use in a nationally representative sample.

CONCLUSIONS

im-proving oral health by recommending that they visit the dentist. Moreover, children of parents who were regular users of dental care were more likely

to visit the dentist. Dental use among children, therefore, might be improved by increasing access to care for par-ents. Future research should examine

potential interventions to increase dental recommendations by primary health care providers and determine their dental outcomes.

REFERENCES

1. Newacheck PW, Hughes DC, Hung YY, Wong S, Stoddard JJ. The unmet health needs of America’s children.Pediatrics.2000;105(4 pt 2):989 –997

2. US Department of Health and Human Ser-vices.Oral Health in America: A Report of the Surgeon General—Executive Summary. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and

Human Services, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, National Insti-tutes of Health; 2000

3. US Department of Health and Human Ser-vices.Guide to Children’s Dental Care in Medicaid. Baltimore, MD: Centers for Medi-care and Medicaid Services; 2004

4. dela Cruz GG, Rozier RG, Slade G. Dental screening and referral of young children by pediatric primary care providers. Pediat-rics. 2004;114(5). Available at: www. pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/114/5/e642

5. Hale KJ; American Academy of Pediatrics, Section on Pediatric Dentistry. Oral health risk assessment timing and establishment of the dental home.Pediatrics.2003;111(5 pt 1):1113–1116

6. Lewis CW, Grossman DC, Domoto PK, Deyo RA. The role of the pediatrician in the oral health of children: a national survey. Pedi-atrics. 2000;106(6). Available at: www. pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/106/6/e84

7. Schafer TE, Adair SM. Prevention of dental disease: the role of the pediatrician.Pediatr Clin North Am.2000;47(5):1021–1042, v–vi 8. Sanchez OM, Childers NK. Anticipatory

guid-ance in infant oral health: rationale and rec-ommendations. Am Fam Physician.2000; 61(1):115–120, 123–124

9. Chu M, Sweis LE, Guay AH, Manski RJ. The dental care of U.S. children: access, use and referrals by nondentist providers, 2003.

J Am Dent Assoc.2007;138(10):1324 –1331 10. Bader JD, Rozier RG, Lohr KN, Frame PS.

Phy-sicians’ roles in preventing dental caries in preschool children: a summary of the evi-dence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force.Am J Prev Med.2004;26(4):315–325 11. Irwin CE Jr, Adams SH, Park MJ, Newacheck

PW. Preventive care for adolescents: few get visits and fewer get services.Pediatrics.

2009;123(4). Available at: www.pediatrics. org/cgi/content/full/123/4/e565

12. Cohen J.Design and Methods of the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Household Com-ponent. Rockville, MD: Agency for Health Care Policy and Research; 1997. AHCPR pub-lication 97-0026

13. Andersen RM. Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: does it matter?J Health Soc Behav. 1995;36(1): 1–10

14. Mouradian WE, Wehr E, Crall JJ. Disparities in children’s oral health and access to den-tal care.JAMA.2000;284(20):2625–2631 15. Vargas CM, Dye BA, Hayes K. Oral health care

use by US rural residents, National Health Interview Survey 1999.J Public Health Dent.

2003;63(3):150 –157

16. Beil H, Mayer M, Rozier RG. Dental care uti-lization and expenditures in children with special health care needs.J Am Dent Assoc.

2009;140(9):1147–1155

17. Vargas CM, Ronzio CR. Disparities in early childhood caries.BMC Oral Health.2006; 6(suppl 1):S3

18. Lewis C, Robertson AS, Phelps S. Unmet den-tal care needs among children with special health care needs: implications for the medical home. Pediatrics. 2005;116(3). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/ content/full/116/3/e426

19. Grembowski D, Spiekerman C, Milgrom P.

Linking mother and child access to dental care. Pediatrics. 2008;122(4). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/ 122/4/e805

20. Liu J, Probst JC, Martin AB, Wang JY, Salinas CF. Disparities in dental insurance coverage and dental care among US children: the Na-tional Survey of Children’s Health. Pediat-rics.2007;119 (suppl 1):S12–S21

21. McPherson M, Arango P, Fox H, et al. A new definition of children with special health care needs.Pediatrics.1998;102(1 pt 1): 137–140

22. Bethell CD, Read D, Stein RE, Blumberg SJ, Wells N, Newacheck PW. Identifying children with special health care needs: develop-ment and evaluation of a short screening

instrument. Ambul Pediatr. 2002;2(1): 38 – 48

23. American Academy of Pediatrics, Commit-tee on Practice and Ambulatory Medicine and Bright Futures Steering Committee. Recommendations for preventive pediatric health care.Pediatrics.2007;120(6):1376 24. American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry.

Clinical guideline on periodicity of examina-tion, preventive dental services, anticipa-tory guidance, and oral treatment for chil-dren.Pediatr Dent.2004;26(7 suppl):81– 83 25. American Dental Association. ADA state-ment on early childhood caries. Available at: www.ada.org/2057.aspx. Accessed Septem-ber 30, 2008

26. Grimshaw JM, Winkens RA, Shirran L, et al. Interventions to improve outpatient refer-rals from primary care to secondary care.

Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;(3): CD005471

27. Crawford AN, Lennon MA. Dental attendance patterns among mothers and their children in an area of social deprivation.Community Dent Health.1992;9(3):289 –294

28. Gratrix D, Taylor GO, Lennon MA. Mothers’ dental attendance patterns and their chil-dren’s dental attendance and dental health.

Br Dent J.1990;168(11):441– 443

29. Kinirons M, McCabe M. Familial and mater-nal factors affecting the dental health and dental attendance of preschool children.

Community Dent Health. 1995;12(4): 226 –229

30. Isong IA, Zuckerman KE, Rao SR, Kuhlthau KA, Winickoff JP, Perrin JM. Association be-tween parents’ and children’s use of oral health services. Pediatrics.2010;125(3): 502–508

31. Sohn W, Ismail A, Amaya A, Lepkowski J. De-terminants of dental care visits among low-income African-American children. J Am Dent Assoc. 2007;138(3):309 –318; quiz 395–396, 398

32. Pierce KM, Rozier RG, Vann WF Jr. Accu-racy of pediatric primary care providers’ screening and referral for early child-hood caries. Pediatrics. 2002;109(5). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/ content/full/109/5/e82

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2009-2311 originally published online July 26, 2010;

2010;126;e435

Pediatrics

Heather A. Beil and R. Gary Rozier

Services

Updated Information &

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/126/2/e435

including high resolution figures, can be found at:

References

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/126/2/e435#BIBL

This article cites 21 articles, 8 of which you can access for free at:

Subspecialty Collections

_sub

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/child_health_financing

Child Health Financing

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/advocacy_sub

Advocacy

ub

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/dentistry:oral_health_s

Dentistry/Oral Health

following collection(s):

This article, along with others on similar topics, appears in the

Permissions & Licensing

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/Permissions.xhtml

in its entirety can be found online at:

Information about reproducing this article in parts (figures, tables) or

Reprints

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/reprints.xhtml

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2009-2311 originally published online July 26, 2010;

2010;126;e435

Pediatrics

Heather A. Beil and R. Gary Rozier

Children

Primary Health Care Providers' Advice for a Dental Checkup and Dental Use in

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/126/2/e435

located on the World Wide Web at:

The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is

by the American Academy of Pediatrics. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 1073-0397.