More than

temporary:

Australia’s

457 visa

This report was prepared by the Migration Council Australia.

The MCA is an independent non-partisan, not-for-profit body established to enhance the productive benefits of Australia’s migration and humanitarian programs.

Our aim is to promote greater understand of migration and settlement and to foster the development of partnerships between corporate Australia, the community sector and government.

We would like to thank the Department of Immigration and Citizenship. They funded the survey of migrants and employers. The Social Research Centre performed the survey. The MCA receive funding from the Department of Immigration and Citizenship. For more information about the MCA, please go to: www.migrationcouncil.org.au All material published by the MCA is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommerical 3.0 Unported License.

Executive summary 3

Chapter 1:

About the program 7

Sponsorship 7

Nomination 8

Visa grant 8

Compliance and monitoring 8

Program trends 9

Chapter 2:

Survey methodology 10

Chapter 3:

Contribution to the labour market 12

Migrant satisfaction 12

Employer satisfaction and usage 16

Union membership 18

Recommendations 20

Chapter 4:

Temporary migration and the global economy 21

Skills development and training 21

National innovation system 24

Recommendations 26

Chapter 5:

Inclusion and community 27

Sense of belonging 28

Discrimination and participation 32

Recommendations 32

Chapter 6:

History of the 457 visa 33

Introduction 33

The Roach Report 35

Introduction of Temporary Business Visas 38

Review and reform under the Howard Government 40

Joint Standing Committee on Migration – “Temporary visas…permanent benefits” 46

Review and Reform under the Rudd-Gillard Governments 48

Chapter 7:

International comparisons of temporary migration 62

Canada 64

New Zealand 65

The United Kingdom 65

The United States 66

Conclusion 68

List of acronyms

ABS Australian Bureau of Statistics ACTU Australian Council of Trade Unions AMEP Adult Migrant English Program

ASCO Australian Standard Classification of Occupations AWPA Australian Workforce and Productivity Agency CSOL Consolidated Skilled Occupation List

DEEWR Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations DIAC Department of Immigration and Citizenship

DIMA Department of Immigration and Multicultural Affairs EMA Enterprise Migration Agreement

IELTS International English Language Testing System JSCM Joint Standing Committee on Migration NESB Non-English speaking background

TSMIT Temporary Skilled Migration Income Threshold UNHCR United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees UNICEF United Nations Children’s Fund

Over the past decade, Australia’s migration program has evolved. It

has transformed from a program to source labour into a tool which

supplements our skill base and imports knowledge. It has become

less permanent but more responsive; less centrally set and more

demand driven. At the heart of this transformation is the growth of

temporary skilled migration.

Over the past decade, Australia’s migration program has evolved. It has transformed from a program to source labour into a tool which supplements our skill base and imports knowledge. It has become less permanent but more responsive; less centrally set and more demand driven. At the heart of this transformation is the growth of temporary skilled migration.

Approximately 190,000 temporary migrants now live and work in Australia as primary and secondary 457 visa holders.1 To put

this in perspective, the total number of 457 visa holders currently in Australia is now roughly equal to the annual intake under our permanent migration program, but only a fraction of the total number of the 1.2 million temporary migrants residing in Australia at any one time.2

The 457 visa program is a purpose-built labour market policy tool and part of a new era of people movement management. A growing portion of the permanent program comprises employer-sponsored migrants. Of these permanent migrants, more than 70 per cent of those sponsored already reside in Australia on temporary 457 work visas. This is the newest policy advancement, a two-step migration process, allowing demand to drive the flow of skills into our labour force.

1 Figures include secondary visa holders and are an estimation based on the average rate of grants for secondary visa holders.

2 This figure includes 457 visa holders, international students, working holiday makers and New Zealand citizens.

The growth of temporary skilled migration means we now have two “migration programs” to address skills shortages that are tied together and inextricably linked: the 457 program and the permanent skilled migration program. Temporary skilled migration has become an automatic relief valve, cushioning the relationship between labour market needs and the time lag inherent to centrally planned permanent migration. Surges in skilled labour requirements or dips in economic activity see numbers of temporary skilled workers ebb and flow. The program helps to maintain Australia’s international competitiveness and is critical to our aspirations to become a regional hub.

Temporary skilled migration has received extensive media coverage and political attention in the almost two decades since the 457 visa was first introduced. Interest in the program reflects the inherent tension in providing a flexible and responsive tool to assist business in accessing the skilled labour they require to satisfy Australia’s labour and economic needs, and enhance our international competitiveness, while also protecting Australian workers, their jobs, training and conditions. In particular there have been periodic reports of exploitation of overseas workers and rorting of aspects of the program by employers.

However, we also find indicators that a small number of employers are misusing the program, highlighting the need for effective compliance and monitoring systems. In particular, responses relating to wages and conditions require further monitoring and investigation. Moreover, the survey data indicates that unions could play an increased role in enhancing the effectiveness of the program, as 457 visa holders who are union members are more satisfied with their employment and more likely to stay in Australia over the long term.

Key findings:

t Workers on 457 visas enjoyed high levels of satisfaction, with 88 per cent either very satisfied or satisfied with their relationship with their employer.

t 71 per cent of 457 visa holders intended to apply to become permanent residents after their visa expired.

t 85 per cent of employers were satisfied or very satisfied with the program.

t 2 per cent of 457 visa holders reported incomes less than the threshold income set by regulation.

t Only 7 per cent of 457 visa holders indicated that they were affiliated with a union.

Chapter 4 examines the contribution of the program to broader economic policy outcomes, including skills development and innovation. The survey results reinforce that skills transfer and knowledge from 457 visa holders play an important part in building Australia’s human capital. Temporary migration does not just fill skills shortages; it addresses skills deficits by training Australian workers. The program is critical in keeping us competitive in the era of international knowledge wars, when industry innovation is global.

Despite being subject to such attention, to date there has been little comprehensive analysis undertaken of the 457 program and its operation. This is particularly concerning given the size of the program, its significance in the calculus of investment and its impact on Australia’s economic growth and sustainability.

This report provides the first comprehensive analysis of wide-scale survey data.3 It

draws on a survey, commissioned by the Department of Immigration and Citizenship, of some 3,800 visa holders and 1,600 companies to examine the operation of the temporary skilled migration program from the perspective of both visa holders and employers. It also examines the impact of the program at a national level, including its affect on innovation and skills development. Chapter 1 of this report provides an overview of the 457 program as it presently operates, noting the circumstances in which primary and secondary 457 visa holders come to Australia.

Chapter 2 describes the methodology of the survey, while the findings of the survey are detailed in Chapter 3 through Chapter 5. Chapter 3 looks at the performance of the program and its impact on the labour market. It finds that, on the whole, the program is meeting the needs both of employers and 457 visa holders. In particular there is a high level of job satisfaction, demonstrating that 457 visa holders are integrating well into the Australian workforce. Employer usage generally reflects the policy intention of the program and employers indicate a high level of support for the current settings.

3 Other surveys have occurred in the past providing valuable insights into the program however they contained a significantly smaller sample. The work of McDonald, Hugo, Khoo and Voigt-Graf in particular laid the groundwork for a more detailed understanding of the 457 program.

Executive summary

In analysing the survey findings, the report concludes that Australia is missing the full potential of gains from temporary migration. Spouses of 457 visa holders, while having work rights, do not receive any support and can struggle in terms of employment outcomes, English language acquisition and understanding of Australian culture. Assisting these migrants with post-arrival support would improve labour market participation rates. Further, the report finds that the rapid growth of temporary migration has not been matched by consideration of its impact and contribution to broader economic policies. As such, the report puts forward a series of recommendations for further research and policy development. A full list of recommendations can be found below. Given the flexible and fluid nature of temporary skilled migration, policy settings for this program require constant monitoring and review. Chapter 6 of this report provides a full historical analysis of the evolution of the 457 program, from inception to date. The picture that emerges is of a program that has been constantly adjusted and fine-tuned to meet changing circumstances, with an increased focus on regulation and compliance mechanisms over time. While the review initiating Australia’s temporary skilled migration program was commissioned by the Keating Government, the 457 visa itself was introduced under the Howard Government in 1996. The first significant phase of program reform, in the early 2000s, was directed towards improving the regime by increasing the ability of employers to better utilise temporary migration. The second phase of reform, starting in 2006, can be classified as a response to instances of exploitation of 457 visa holders and a strict focus on the integrity of the program. The Rudd-Gillard Government continued this tradition of integrity-based reform, albeit with a broader focus to also protect Australian wages and conditions.

Key findings:

t Over three-quarters (76 per cent) of 457 visa holders said they helped to train or develop other workers.

t 68.5 per cent of employers said they were using 457 visa holders to train Australian counterparts.

t An overwhelming majority (86.3 per cent) of visa holders felt that their job in Australia used their skills and training well.

Chapter 5 reflects on the lives of 457 visa holders outside of employment — their social experiences, level of community engagement and sense of belonging. Living in Australia for prolonged periods of time, 457 visa holders are part of our communities. Some fifty per cent will transition to

permanent residency. For those who do return home, their period of stay in Australia will, more often than not, be for a period of years rather than months. Our analysis of the survey also finds that more attention must be paid to secondary visa holders, such as spouses and dependent children. The survey results also indicate that participation of secondary visa holders is critical in the decision to stay in Australia.

Key findings:

t The vast majority of 457 visa holders indicated they were settling into Australia well (on a scale of one to ten, the average was 8.35).

t Participation and employment of spouses (secondary visa holders) is an important factor in choosing to stay on in Australia.

t Participation in sports and hobbies at least monthly was higher than the Australian average.

t Some 18.4 per cent of 457 visa holders from non-English speaking backgrounds indicated that they had faced

discrimination because of their skin colour, ethnic origin or religious beliefs.

Executive summary

Recommendations

1. That the Federal Government increase sponsorship and nomination fees associated with the 457 visa program to act as a price signal, providing a resource pool to strengthen compliance and deliver settlement services.

2. That the Federal Government, in consultation with industry peak bodies and the Australian Council of Trade Unions (ACTU), establish voluntary Australian workplace orientation sessions available for all 457 visa holders.

3. That the Federal Government extend visa condition 8107 from a period of 28 days to 90 days, as recommended in the Deegan Review.

4. That the Federal Government allows any 457 visa holder who has worked continuously in Australia for two years to apply for the transition pathway to permanent residency under the Employer Nomination Scheme irrespective of the number of employers they have worked for.

5. That the Federal Government fund research into immigration policies and their link to Australia’s national innovation and productivity agenda.

6. That peak industry bodies collaborate to undertake an examination of innovation through migration at the enterprise level. 7. That the Federal Government incorporates

analysis of the role of migration in national workforce development strategies and skills and training policy.

8. That the Federal Government extends settlement services and other services that enable social and economic participation to the dependants of 457 visa holders. 9. That the NSW and ACT governments

remove all education expenses associated with the dependent children of 457 visa holders.

10. That the Federal Government, the ACTU and industry peak bodies work together to develop workplace and enterprise level programs to address discrimination and exploitation.

The recommendations proposed in this report are similarly a response to the most recent evolutions in the 457 visa system. The recommendations seek to address current challenges associated with the program, and future-proof it so that it can continue to meet Australia’s economic and broader social needs.

We stress that support for migration programs in Australia should not be taken for granted. The confidence of the Australian community in the migration program is paramount to its success and is contingent on strong and bipartisan political leadership. As such, reforms need to be informed by evidence and need to factor in the potential consequential effects.

The Department of Immigration and

Citizenship (the Department) administers the program. This includes approving employers to use the scheme and granting visas to migrants for entry into Australia. In addition, the Department is charged with monitoring and compliance activities. Further, the Gillard Government recently announced additional powers would be given to the Fair Work Ombudsman to monitor and enforce compliance with 457 visa conditions. Heavy penalties can be levied on employers who abuse the program.

The procedural process to issue a 457 visa consists of three distinct stages. First, an employer must be an organisation approved to sponsor 457 visa holders. The second stage is approval of a particular position for the employment of a 457 visa holder. The final process is the visa grant, which encompasses an assessment of the skills of the worker concerned. More detail on each stage is provided below.

Sponsorship

Several conditions must be met to become an approved sponsor. The employer must be lawfully operating and must pay a

sponsorship fee (currently $420). Additionally, the employer must meet a training

benchmark. Either the employer must have spent one per cent of payroll on training Australian staff or contribute two per cent of payroll to an industry training fund.

Employers must also attest that they have a strong record of employing local labour and non-discriminatory work practices. This regulation has been criticised, as the attestation does not require demonstration by any other methods.

The 457 program enables residence in Australia for the purposes of employment for a period of up to four years. It is only available to skilled workers who have been sponsored by an employer to fill a skills shortage. Employers are made up of private enterprise, academic institutions, and government and non-profit organisations. The key foundation of the 457 program is a focus on skills. Employers can only hire people who have existing qualifications or experience, and only to fill positions in certain skilled occupations.

Workers on 457 visas are found in every industry. They make up approximately one per cent of the total labour market and account for approximately two per cent of our skilled workforce. The 457 program is uncapped, meaning the number of visas granted in any given year is determined by demand. At 31 March 2013, there were 105,600 primary visa holders in Australia. In addition, there are approximately 85,000 secondary visa holders (spouses and children).4

The 457 program is ‘demand-driven’ and is incorporated into the economic cycle. When the economy grows demand increases and more people are sponsored. When the economy slows, such as during the global financial crisis, demand for the program drops off. Use of the 457 program is currently at a historic high. This is attributable to comparatively robust economic conditions with poor economic performance in some parts of the developed world.

4 Taken from the Department of Immigration and Citizenship monthly statistical update for the 457 Program. The update does not release the spouse and children figure. Past figures indicate that for every primary 457 visa holder, there is approximately 0.8 additional visas granted.

The 457 program enables residence in Australia for the purposes of

employment for a period of up to four years. It is only available to

skilled workers who have been sponsored by an employer to fill a

skills shortage.

Importantly, migrants are subject to two visa conditions. Firstly, all migrants must hold private health insurance. The second condition is that each worker who holds a 457 visa can only work for the employer that nominated him or her and in the position they were nominated to undertake. As part of this condition, 457 visa holders cannot cease employment for more than 28 consecutive days. Once in Australia, a worker on a 457 visa can change employers or positions. However, the job needs to be with an employer who is also an approved sponsor and they must again go through the process of nominating for a particular position.

Compliance and monitoring

The Department undertakes a program of monitoring sponsors to “enhance the integrity of temporary economic visas, including the subclass 457 visa program”. Compliance work is performed by a network of 37 inspectors. The focus of compliance is determined by internal risk assessments. Recently, the government expanded monitoring of the 457 program by allowing oversight of the program by the Fair Work Ombudsman. The Ombudsman will now monitor to provision of market salary rates to 457 visa holders and undertake checks to verify that they are performing tasks commensurate with the job description they were nominated to undertake.5 Withan additional 300 inspectors, this provides a safety net.

Table 1: 457 Visa program compliance and monitoring

Active sponsors 22 450

Monitored 1 754

Visits 856

Sanctioned 125

Warned 449

Referred 18

Infringement 49

Successfully prosecuted 1

(Source: Department of Immigration and Citizenship Annual Report 2011-12)

5 See http://www.minister.immi.gov.au/media/bo/2013/bo194313.htm

Nomination

After becoming an approved sponsor, an employer can nominate a position in the business. This position must be an occupation listed on the Consolidated Skilled Occupation List (CSOL). The CSOL contains 649 different occupations (from a total of 1342 possible occupations). Each of these occupations is classified as a ‘skilled’ position as they require a minimum AQF Certificate III and two years of on-the-job training. However, the majority of occupations have a higher skill threshold. There is a fee to nominate each position (currently $85). At this stage, the employer must nominate the name of the migrant who will fill the position and the salary they will be paid. Often employers provide employment contracts or copies of Enterprise Agreements to verify pay rates. Importantly, the salary must be the “market rate”, that is the amount paid in the Australian labour market for that position. A market salary must be demonstrated by showing that an Australian would receive the same income doing the same job. The pay cheques or Enterprise Agreements of other workers can be used to justify income levels for migrants on 457 visas. In addition, the salary must be above the Temporary Skilled Migration Income Threshold (TSMIT), which currently is $51,400. Historically, this figure is indexed every year in July in line with inflation.

Visa grant

After a nomination has been approved, the person identified can apply for a subclass 457 visa. As part of this process, each migrant must demonstrate they have a genuine intention to perform the occupation that they have been nominated to undertake. This involves showing how skills have been acquired, such as formal education or detailing past work experience. Some migrants are also required to undergo a formal English test (there are several broad exemptions to this) and some occupations in Australia require registration and licensing from other bodies (for example nurses and electricians).

Increased usage of the 457 program is now driving changes in the permanent migration program. Workers holding 457 visas dominate categories of permanent residency that are increasing over time. This includes permanent visas that are sponsored by employers.

Additionally, permanent visas are increasingly being granted to migrants who already live and work in Australia. For example, more than half of all permanent visas granted to migrants already in Australia were made to applicants on a 457 visa. In 2011-12, there were 79,287 permanent skilled and family visas granted to migrants in Australia, of which, 40,485 previously held a 457 visa.7

7 Note: The number of visas granted to migrants already in Australia is about 40 per cent of the total migration program – an additional 105,711 skilled and family visas granted offshore, for a total Permanent Migration Program of 184,998. Also note that the transition to permanent residency figures include spouses and children of primary migrants.

Program trends

Since the program’s inception, there has been relatively consistent growth in usage. While the onset of the Global Financial Crisis saw a significant dip in visa grants, activity has since increased to historic levels. At the end of 2011-12, there were 22,450 employers who sponsored at least one 457 visa holder. This represents a 20 per cent increase on the year before, indicating a broadening in uptake.6 Despite this growth, it is important

to place the program in perspective as, overall, workers holding 457 visas make up a small fraction (one per cent) of the labour market.

Graph 1: Primary 457 visa grants, 1997–1998 to 2011–2012

10000 20000 30000 40000 50000 60000 70000 80000

2011 -12 2010

-11 2009

-10 2008

-09 2007

-08 2006

-07 2005

-06 2004

-05 2003

-04 2002

-03 2001

-02 2000

-01 1999

-00 1998

-99

VISA GRA NTS

(Source: the Department of Immigration and Citizenship)

6 Department of Immigration and Citizenship, Annual Report 2011-12, p. 86.

Chapter 2: Survey methodology

For employers to be included, they must have sponsored at least one worker on a 457 visa as of 5 May 2012 who had their visa granted in the period between October 2009 and 30 June 2011. For sponsoring employers, HR managers or persons responsible for hiring employees were asked to respond on behalf of the employer.

Migrants and employers were selected in the sample from records provided by the Department. The questionnaire used in the survey was developed between the Department and the Social Research Centre based on previous research into sourcing migrants (such as the Continuous Survey of Australian Migrants). A stakeholder workshop was held to explore key topics to be covered. The questionnaire was piloted and refined. After the survey was completed, weighting was assigned to data; however, the analysis used in this report is derived from raw data. This is due to the large sample sizes of the survey. The weighted data saw only marginal differences, not influencing the overall themes of the survey.

The following sections provide an analysis of survey data from 3,812 workers on a 457 visa and 1,600 employers who use the program. The total sample size for visa holders was significant, representing approximately 5 per cent of all 457 visa holders in Australia at the time. The survey, funded by the Department of Immigration and Citizenship, was

undertaken by the Social Research Centre in May and June 2012.

To be included in the survey, a migrant must have been in Australia on 5 May 2012 and had their visa granted between October 2009 and June 2011. For the purpose of data analysis, this ensures that all migrant participants had been living in Australia for a minimum of 10 months. This is important as not all 457 visas are granted to migrants who stay. Some employers use the program to transfer existing employees between offices in different countries, such as from regional headquarters to country offices. These 457 visa holders are likely to stay in Australia for shorter periods of time.

Table 2: Collection of survey data

Target

Interviews Sample Completed Interviews Response Rate Interview Length (average) (mins:secs)

Migrant Workers 3,100 15,199 3,812 25.1% 23:34

Current employers 1,500 2,832 1,500 91.7% 8:08

Chapter 2: Survey methodology

Of the 3812 holders of 457 visas surveyed:

t 64 per cent were male

t 36 per cent were female

t 49 per cent were from English-speaking backgrounds

t 51 per cent were from non-English speaking backgrounds.

Translations and interpreters were not used to collect survey data, as 457 visa holders are assumed to be tested for and have a minimum standard of English. Only a small percentage of migrants surveyed indicated difficulty with English after an initial period of living in Australia. 457 visa holders under the labour agreement program were not surveyed.

For all survey questions, there were a range of responses, including for many, “Don’t know” or “Refuse”. Generally, the responses to these questions ranged from one to ten per cent. Data tables are detailed in Appendix A.

Like all surveys, there will be some

sampling error contained. The ‘true value’ is approximately +/- 2 per cent.

It is also useful to mention that the findings in this report are not presented as ‘right’ or ‘wrong’. The survey data provides an indication of migrant and employer satisfaction against a range of questions. There are of course many other

non-migration impacts on satisfaction for both of these groups.

Of the 1,600 employers surveyed, employer size was as follows:

t 23 per cent employed less than 10 staff

t 37 per cent employed between 11 and 50 staff

t 19 per cent employed between 51 and 199 staff

t 21 per cent employed over 200 staff.

Graph 2: Employer size by staff and 457 usage

0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70% 80% 90% 100%

10 or less 11–50 51–199 200+ Total staff Total 457 migrants

Chapter 3: Contribution to the labour market

However, there are concerning indicators that highlight the inherent risk about any temporary migrant work program. In particular, responses regarding wages and conditions require further monitoring and investigation. Moreover, survey data concerning union affiliation indicates that unions could play an increased role in enhancing the effectiveness of the program. For example, 457 visa holders who are union members are more satisfied with their employment and more likely to stay in Australia over the long term.

Migrant satisfaction

The survey indicated very high levels of satisfaction, with 88 per cent of visa holders either very satisfied or satisfied with their relationship with their employer. Only 4 per cent of 457 visa holders were dissatisfied. This compares favourably to Australian satisfaction data. In 2012, general job

satisfaction statistics for the Australian labour market were as low as 54 per cent.9

9 CareerOne.com.au, Hidden Hunters Report, 2012.

The basic objective of the 457 program is to meet skill needs which cannot be effectively met by domestic labour within a reasonable timeframe. Critically, the intention of the program is that it does this without adversely affecting labour market outcomes for Australian workers. Refinement of policy mechanisms associated with Australia’s temporary migration framework has therefore concentrated on calibrating the tools used to achieve both objectives simultaneously. However, to date there has been very little research and analysis evaluating the functioning of the program with respect to these outcomes.8

This survey provides a body of evidence to indicate that the program is meeting the needs of both the majority of employers and the vast majority of 457 visa holders. In particular, a high level of employment satisfaction demonstrates that 457 visa holders are integrating well into the Australian workforce. On the whole, employer usage and attitudes reflect the policy intention of the program and, further, employers indicate a high level of satisfaction and an ongoing commitment to usage.

8 There are, of course, exceptions to this general trend. Professor Peter McDonald, Professor Graeme Hugo, Dr Siew-Ean Khoo and Carman Voigt-Graf conducted significant research into the 457 program throughout the 2000s. More recently, Joo-Cheong Tham has undertaken useful research.

This survey provides a body of evidence to indicate that the

program is meeting the needs of both employers and 457 visa

holders. In particular, a high level of employment satisfaction

demonstrates that 457 visa holders are integrating well into the

Australian workforce. On the whole, employer usage and attitudes

reflect the policy intention of the program and, further, employers

indicate a high level of satisfaction and an ongoing commitment to

usage.

In terms of earnings, 76 per cent of visa holders were either very satisfied or satisfied with their wages. While there are no exact commensurate national level data, the finding is in accord with results from other similar surveys of the general Australian population. For example, the HILDA survey, asks for a 0 to 10 rating for income satisfaction. Across the broad Australian community, the average result for income satisfaction was of 7.0 in 2009.10

Promisingly when examining a breakdown between English and non-English speaking background 457 visa holders there was very little difference in terms of income satisfaction. This is in contrast to migrants in the labour market, where higher

unemployment and lower participation are apparent for migrants. While there is likely to be a mismatch in wage expectations between migrants originating from different development contexts, it is encouraging that there is little disparity in terms of migrant perspectives. However, it is important to note that 11 per cent of 457 visa holders were either dissatisfied or very dissatisfied with their earnings. While HILDA also shows some level of dissatisfaction of Australian attitudes towards earnings, the survey data regarding wages indicate that some visa holders are paid significantly less than they are entitled to receive.

Approximately 5 per cent of 457 visa holders did not feel as though their employers were meeting their obligations. The most common responses were agreements not honoured (4.3 Per cent), issues with living away from home allowance (3.9 Per cent), over-worked, lack of over-time payments (3.8 Per cent), discrimination (3.0 Per cent) and feel restricted from leaving (2.6 Per cent).

10 Families, Incomes and Jobs, Volume 7: A Statistical Report on Waves 1 to 9 of the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) Survey 2012 Note: While this is an imperfect comparison due to the different sample populations and methodology, this appears to infer at some level that satisfaction levels for migrant earnings are somewhat similar to Australian averages. The HILDA survey collects information about economic and subjective well-being, labour market dynamics and family dynamics. It is a longitudinal survey that has been undertaken since 2001. It is funded by the Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs and designed and managed by the Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research.

Chapter 3: Contribution to the labour market

Table 3: Migrant satisfaction: Relationship with employer by industry type

Accommodation and food services 94% Administrative and Support Services 84% Agriculture, Forestry and Fishing 86% Arts and Recreation Services 88%

Construction 86%

Education and Training 88%

Electricity, Gas, Water and waste

services 77%

Financial and Insurance Services 86% Health Care and Social Assistance 90% Information media and

telecommunications 88%

Manufacturing 92%

Mining 92%

Other Services 89%

Professional, Scientific and Technical

Services 88%

Public Administration and Safety 100% Rental, Hiring and Real Estate

Services 82%

Retail Trade 86%

Transport, Postal and Warehousing 97%

Wholesale Trade 93%

Total 88%

In terms of promotion prospects, 64 per cent of visa holders said they were either satisfied or very satisfied by the opportunities for a promotion in their current job, with only 14 per cent dissatisfied. This is a significant statistic, as the prospect of promotion is likely to weigh heavily in any decision to stay permanently. Moreover, the extent to which employers provide opportunities to progress speaks to their intention in terms of usage of the program and the premium placed on the skills of 457 visa holders.

Chapter 3: Contribution to the labour market

The Deegan Review also raised concerns about the position of working age children who were secondary visa holders, noting that claims had been made during consultations that children of primary visa holders who had left school had “been persuaded to work under irregular and exploitative conditions for employers who have claimed that to ‘regularise’ the situation (and pay correct wages etc) would jeopardise that person’s status as a dependent of the primary visa holder and their right to remain in Australia.”13

The survey does not ask about the working conditions or wages of secondary visa holders, including spouses. Arguably, secondary visa holders who may not speak English well or at all and may be unskilled are particularly vulnerable to exploitation. Further research on the work patterns of secondary visa holders will be important in determining the extent and risk of exploitation.

Critically, 88 per cent of 457 visa holders said they had working conditions that were equal to Australian colleagues. Though it is disquieting that 7 per cent said their conditions were not equal. Conversely, 34 per cent of migrants said they felt they worked harder than Australian colleagues, with 65 per cent indicating their work ethic was about on par with their Australian colleagues. While this is a subjective question, it provides important insight into how 457 visa holders view themselves relative to their colleagues in the workforce.

The survey also indicated a strong desire on the part of 457 visa holders to see the program as a pathway to permanent residency in Australia. About half (48 per cent) of all 457 visa holders indicated the reason for applying for the visa was to live in Australia or to become a permanent resident. Moreover, 71 per cent intended to apply to become permanent residents after their visas expired.

13 ibid, p.58.

It is cause for considerable concern that approximately 2 per cent of 457 visa holders indicated that their earnings were less than $40,000, both when they first arrived and when they were surveyed (June 2012). This is significantly below the salary threshold of $51,400 and indicates that a small proportion of employers are abusing the program. Given the skill spectrum associated with the program, it is also highly unlikely that these visa holders are being paid wages that are comparable to market salary wages. It is worth mentioning that these migrants are not concentrated in any one industry or location. It is also notable that a full 25 per cent of 457 visa holder responses to questions about their salary were ‘Don’t know’ or ‘Refuse’. This was the single question in the survey that elicited this type of response.

It is also concerning that approximately 1.5 per cent of 457 visa holders stated that they did not have any Australian colleagues. When combined with the restrictions on labour mobility and low levels of monitoring and enforcement, this can create conditions conducive to exploitation. However, it is worth noting that there is very little correlation between those migrants who are receiving below threshold salary levels and those who work by themselves (0.05 per cent of total survey).

The final report of the Deegan Review also made the critical point that “Those visa holders who are susceptible to exploitation are also reluctant to make any complaint which may put their employment at risk.”11

This is particularly true of 457 visa holders with limited English skills who wished to remain in Australia and gain permanent residency, but who were heavily reliant on their employer for their continued presence in Australia and consequently vulnerable and open to exploitation.12

11 Barbara Deegan, Visa subclass 457 integrity review: final report, October 2008, accessed at http://www.immi.gov.au/skilled/skilled-workers/_pdf/457-integrity-review.pdf, p.23.

Chapter 3: Contribution to the labour market

The most recent and arguably most comprehensive review of the program, the Deegan Review, explicitly noted the need for more information to be provided to 457 visa holders upon their entry to Australia and suggested orientation support. The Review also flagged the possibility of providing services through additional charges to the primary users and beneficiaries of the program, namely business. By earmarking money raised by increasing visa fees, the government could fund post-arrival support in a revenue neutral way.

The Deegan Review also highlighted the need for 457 visa holders to be given

greater agency in their relationship with their employer. Currently, 457 visa holders can only go without a sponsored employed for 28 days under the terms of their visa. In the event of a breakdown in the relationship with their employers, 28 days is arguably too little time to secure alternative employment or to see through an unfair dismissal claim. The Deegan review recommended this time limit be extended to 90 days. By affording 457 visa holders more time to remain in Australia without a sponsor, this acts to loosen the direct tie to each employer.

About 40 per cent of 457 visa holders indicated they used migration agents. Like a tax agent, a migrant agent helps immigrants with associated paper work and dealing with the administration of attaining a visa. In Australia, migration agents must be formally registered with the Office of the Migration Agents Registration Authority, or MARA. This organisation regulates how migration agents can behave in providing advice to immigrants. 457 visa holders were satisfied with migration agents in Australia with 81 per cent responding positively about their experience while 7 per cent expressed dissatisfaction.

The survey did not ask the reason for dissatisfaction and further research on this issue is recommended. The ACTU website highlights that overseas visa holders are vulnerable to exploitation because of the potential for recruitment and/or migration agents to provide misinformation during the recruitment process; language barriers; a lack of traditional support and family networks in Australia; unfamiliarity with the way the Australian legal and administrative system works; and a lack of knowledge of their rights under Australian law and low rates of union membership.14

A high proportion of 457 visa holders are from non-English speaking countries (notably China and India) where hiring, HR and work practices are not comparable with Australia, and cultural practices are significantly different. A lack of knowledge of the

Australian context diminishes the capacity of the primary 457 visa holder to engage with their rights in the workplace and reduces their ability to participate in the broader Australian community.

14 Australian Council of Trade Unions, Temporary Overseas Workers, http://www.actu.org.au/Issues/OverseasWorkers/default.aspx

Chapter 3: Contribution to the labour market

In terms of specific occupations, professional vacancies were the most difficult to fill for larger firms. Fifty-one per cent of firms with over 200 employees found it difficult to hire local professionals, compared to 30 per cent for firms of 10 or fewer people. A similar pattern is evident for vacancies for community and personal service positions; 14 per cent for larger firms compared to 5 per cent for the smallest firms. The pattern is reversed for trades and technician workers, with 32 per cent of firms with 10 employees or fewer finding it difficult to fill trades workers compared to 22 per cent for firms of over 200 employees.

Growth in different industries is reflected geographically. Trades and technician workers are more difficult to fill in Western Australia (43 per cent) than in Victoria (19 per cent). This corresponds with the economic profile of each state; construction and mining related sectors are growth industries in Western Australia, while services are a growth area for Victoria.

There was a wide range of responses as to why employers find it difficult to fill vacancies from the local labour market. Apart from the lack of skills locally, other reasons stated include better paid jobs in other industries (11 per cent), remote location business (9 per cent), Australians don’t like the job (8 per cent) and have a poor attitude (5 per cent), and other employers in the same industry offering more income (5 per cent).

In terms of hiring practices, the top four methods of recruitment were a referral from existing networks (29 per cent), approached by the employee (26 per cent), an internet ad (24 per cent) and through a recruitment agency (19 per cent). Larger firms were more likely to use a recruitment agency and internet ads while smaller firms relied more heavily on networks.

Employer satisfaction and usage

Employers who sponsor 457 visa holders show overwhelming support, with 85 per cent affirming they are satisfied or very satisfied with the program. When compared to other public policy initiatives targeted at business, this figure is significant. Other public policies, such as supporting small businesses to grow and invest, only attract minimal support.15A concerted government focus on processing times has reduced the wait associated with the program while fees are comparatively low. The satisfaction finding is in accord with survey feedback from business in relation to regulatory engagement with the Department vis-à-vis other government regulatory authorities. The Australian Chamber of Industry and Commerce’s National Red Tape Survey ranks the level of red tape associated with engagement with the Department as significantly lower than other agencies.16

In the majority, employer usage and attitudes reflect the policy intention of the program. Eighty-three per cent of employers responded that they found it very or

somewhat difficult to hire or employ workers from the local labour market. Overall, there was relatively little difference between businesses of different sizes. Employers in smaller states tended to experience more difficulty finding workers than larger states. Respondents noted that professionals (38 per cent), trades workers (26 per cent) and managers (9 per cent) were the most difficult roles to fill. It is worth noting that these figures are in accord with the overall occupation mix in the 457 program (52 per cent, 25 per cent and 14 per cent, respectively).

15 See http://www.smh.com.au/small-business/startup/startups-need-more-govt-support-survey-20121108-29060.html.

16 Australian Chamber of Commerce and Industry 2012, National Red Tape Survey.

Chapter 3: Contribution to the labour market

Case study

The Accommodation and Food Services industry employs about 780,000 people, making it the 7th largest industry in Australia in terms of overall employment. Traditionally lower skill levels and lower wage rates have meant that accommodation and food services have been a below average user of the 457 program, however over the past 18 months applications have surged. The average base salary for the industry is $55,000 compared to the $83,000 for the program overall.

In 2012-13, the industry has recorded a record share of the overall program, with 9.4 per cent of overall 457 visa grants. Driving this increase has been the rise in nominations of Cooks, likely the number one occupation for the 2012-13 program year.

Within the industry, there is strong support for the program. Des Crowe, CEO of the Australian Hotels Association, says that the hotel sector is a perfect example where more workers will be needed in the future.

“Hotels in Australia are a diverse industry. We have employers that are owner-operated and in regional areas to larger employers in global cities like Sydney. These diverse businesses generally share the same difficulties in finding skills and labour from the local workforce. If current trends continue, by 2020 an estimated 56,000 vacancies will be available based on the Government’s own research.”

“The 457 program can fill some of these vacancies, such as Cooks and Chefs, but our members are also in need of workers in lower skilled occupations that aren’t eligible for the 457 program.”

“The salary threshold is too high for some occupations where the industry has skills and labour shortages, while other occupations where there is a demand for more workers are not eligible for the program, such as Hotel Service Managers, Food Service workers and administration staff.”

Des Crowe says part of the difficulty is that existing labour market programs designed to get people into the labour market are failing industries like the Hotel sector.

“Our industry isn’t classified as a priority industry. This means there are basically no connections between employers who have vacancies and programs like Job Services Australia. The AHA has participated in previous Employer Broker Programs which have been successful in the past, current programs aren’t working. This hurts the industry and economy as vacancies go unfilled.”

Chapter 3: Contribution to the labour market

To date, the 457 program has largely been viewed as an exclusively “immigration” program. A more nuanced understanding would incorporate the program into a broader labour market discussion. Statistics relating to the usage of the

program, particularly the trend to preference 457 visa holders, indicate that there is a need to strengthen the price signal of engaging foreign labour. As such, strengthening the price signal through an increase in the charge to nominate a 457 visa holder is recommended. Currently this charge is $85 per nomination. This should be increased to ensure that more businesses look to hire Australian workers where available. In addition, the charge to become a sponsor of 457 visa holders is $420. This should be increased to create incentive to look to local Australian workers before hiring 457 migrants. However, for employers who are unable to find Australian labour, the additional fee is unlikely to be prohibitive compared to exhaustive recruitment costs. To improve labour market outcomes, these fees and charges should be used to provide migrant support on a needs basis.17

Union membership

The survey data on union membership show that 457 visa holders who are union members are more satisfied with their employment and more likely to stay in Australia over the long term.

The survey asked visa holders to indicate whether or not they were members of a trade union. Only 7 per cent of those surveyed indicated that they were affiliated with a union. This compares poorly with the Australian average of 18 per cent.18 Females

were more likely to be union members (11.3 per cent) than males (5.1 per cent). The gender difference is likely to be driven by membership patterns across industries. Service sectors with high levels of female participation also tend to have higher rates of unionisation.

17 Visa fees and charges are subject to annual revisions.

18 Australian Bureau of Statistics 2011, Employee Earnings, Benefits and Trade Union Membership. http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/ Latestproducts/6310.0Main%20Features2August%202011?opendo cument&tabname=Summary&prodno=6310.0&issue=August%20 2011&num=&view=.

The majority of employers indicated that they were equally satisfied (61 per cent) with Australian and 457 visa holders in the workplace. However, among those employers that indicated a preference there was a greater level of support for 457 visa holders; 27 per cent are more satisfied with 457 visa holders, against only 6 per cent who are more satisfied with Australians. Satisfaction rates appear to be driven in part by firm size. Smaller firms have substantially higher satisfaction responses relative to larger firms. Thirty-eight per cent of firms with 10 or fewer employees are more satisfied with 457 visa holders, compared to just 13 per cent of firms with 200 or more employees. This is perhaps to be expected given within larger employers it becomes more difficult to distinguish between employees.

Graph 3: Employer satisfaction by employee

0% 20% 40% 60% 80%

NUMBER OF EMPLOYEES IN BUSINESS 10 or less 11–50 51–199 200+ Total

More satisfied 457s Equally satisfied More satisfied Australians

A preference toward 457 visa holders and difficulty filling vacancies allude to a broader sense of dissatisfaction with the local labour market. Moreover, high overall program satisfaction ratings indicate that the program has become more than a temporary stopgap. For employers, the program is increasingly part of workforce planning.

Chapter 3: Contribution to the labour market

Case study

Since the inception of the 457 program, the ACTU has been concerned that without significant regulatory safeguards, temporary labour has the potential to undermine Australian wages and conditions.

The ACTU also holds strong concerns that temporary sponsorship arrangements make 457 visa holders vulnerable to exploitation.

In March this year the ACTU established a confidential hotline to assist 457 visa holders who are being exploited by their employer. Since the line has been operating the ACTU has received a host of complaints including:

t A farm where 15-20 workers with 457 visas are living in very cramped accommodation, working long hours and rarely leaving the site. The caller said there are OHS issues related to the use of chemicals and many of the workers are presenting at a local medical centre with various health problems.

t A factory where workers are working about 100 hours a week, not only in production work but are then directed to some security work as well.

t An establishment where about 40 per cent of workers are on 457 visas. The workers understood they were being employed as Thai masseurs, but once here have been told if they don’t have sex with clients they will be sacked.

t Reports of a construction team of 457 visa workers being paid about one third of their Australian counterparts’ wages.

t A construction site in Melbourne, which relies heavily on 457 visas, where the workers are not wearing goggles or masks and the scaffolding is unsafe.

t The case in Werribee where 457 visa workers were flown in over the top of local unemployed skilled workers to work on a City West Water project. There have been subsequent reports that workers are working 70-80 hours a week with no overtime. The ACTU maintains that increased resources for compliance and the provision of information on Australian workplace rights are key to preventing exploitation.

Chapter 3: Contribution to the labour market

These results point to a greater role for the union movement in the process of settlement and cultural adjustment. Unions also play an important role in shaping the discussion around how 457 visa holders exist in society and the labour market. Further, access to 457 visa holders and union involvement in the program helps to safeguard the integrity of the program.

Recommendations

t That the Federal Government increase sponsorship and nomination fees associated with the 457 visa program to act as a price signal, providing a resource pool to strengthen compliance and deliver settlement services.

t That the Federal Government, in consultation with industry peak bodies and the Australian Council of Trade Unions (ACTU), establish voluntary Australian workplace orientation sessions available for all 457 visa holders.

t That the Federal Government extend visa condition 8107 from a period of 28 days to 90 days, as recommended in the Deegan Review.

t That the Federal Government allow any 457 visa holder who has worked continuously in Australia for two years to apply for the transition pathway to permanent residency under the Employer Nomination Scheme irrespective of the number of employers they have worked for.

Indeed, the industries with the highest membership rates were health care and social assistance (24.5 per cent) and

education and training (11.7 per cent). Union membership rates for the health care and social assistance industry were surprisingly high, given the national industry rate is just under 30 per cent.19 By comparison,

the national rate of membership for the education and training industry was substantially higher than the rate indicated in the 457 visa holder survey, at 35 per cent.20

Other industries with above average migrant union membership were construction (10.3 per cent) and electricity, gas, water and waste services (10.4 per cent). Some industries, such as accommodation and food services (0.7 per cent), mining (0.0 per cent), ICT (0.7 per cent), financial services (0.5 per cent) and professional and scientific services (1.9 per cent) showed significantly low levels of union membership.

An analysis was undertaken of union membership against a set of satisfaction indicators. Critically, the finding is that 457 visa holders who are union members are significantly more satisfied with their jobs. Visa holders who were union members were 8.7 per cent more likely to be satisfied with their income, 5.6 per cent more likely to feel their job was interesting; 7.0 per cent more likely to be satisfied with their prospects of a promotion and 10.4 per cent more likely to have opportunities for training.

Union membership was also a determinant of intentions to settle in Australia.

Approximately 8.5 per cent of migrants who intended to stay in Australia were union members, while less than 2 per cent of those intending to leave held membership. This could be attributed to varying factors. However membership in a trade union can play a role in creating a sense of social acceptance and creates a bond with co-workers. Union membership can also provide additional benefits such as an independent source of advice and can lead to a greater sense of security.

19 ibid. 20 ibid.

Chapter 4: Temporary migration and the global

economy

Firstly, some contend that the immediacy of the 457 scheme creates a disincentive for employers to invest in long-term training solutions for Australian employees. If skills shortages can be addressed as they arise, there is no enticement to plan for future needs. As such, over the long term, it is assumed that the very existence of the 457 scheme changes the workforce investment calculations of employers.21

Secondly, it has been argued that the program places downward pressure in hiring Australians, reducing the attractiveness of up-skilling for Australian workers. This, in turn, affects the decision of local workers to invest in further education and skills development.22

The third contention is that there is little incentive for Australian employers using the program to provide further training to 457 visa holders, as their employment is temporary. Any skills learnt would leave with them and would increase the skill base of global competitors.

21 ACTU submission to the Joint Standing Committee on Migration Inquiry into Temporary Business Visas, February 2007, http:// www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/House_of_ Representatives_Committees?url=mig/457visas/subs/sub039.pdf . 22 Birrell, B and Healy E, The Impact of Immigration on the Australian

Workforce, Centre for Population and Urban Research, February 2013, http://artsonline.monash.edu.au/cpur/files/2013/02/Immigration_ review__Feb-2013.pdf.

The survey results reinforce that skills transfer and knowledge from 457 visa holders play an essential part in building Australia’s human capital. Temporary migration does not just fill skills shortages; it addresses skills deficits by training Australian workers. It is critical in keeping us competitive in the era of international knowledge wars, when industry innovation is global. In effect, Australia’s temporary migration system is our answer to the “brain drain”: that is, brain circulation. The flow of people has not only helped us to keep pace, it also has created a skills pull in some sectors that has enabled Australia to lead innovation.

Skills development and training

From its inception, the impact of the 457 scheme on our skill base has been framed as a provisional stopgap to address short-term skills shortages. The perception is that 457 visa holders are only here on a temporary basis, and are not seen as adding permanently to our skills capacity. Indeed, long-term, the program is perceived as having a negative impact on national workforce planning and development by changing the investment calculus of employers and Australian employees in relation to training. This argument is based on three assumptions.The survey results reinforce that skills transfer and knowledge from

457 visa holders play an essential part in building Australia’s human

capital. Temporary migration does not just fill skills shortages; it

addresses skills deficits by training Australian workers. It is critical in

keeping us competitive in the era of international knowledge wars,

when industry innovation is global.

Chapter 4: Temporary migration and the global

economy

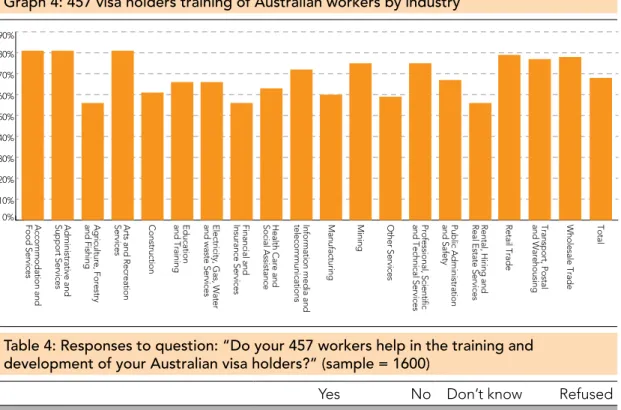

Table 4: Responses to question: “Do your 457 workers help in the training and development of your Australian visa holders?” (sample = 1600)

Yes No Don’t know Refused

Total 68.9% 19.6% 1.5% 10.1%

Local organisation with operations

only within one state or territory 64.3% 22.3% 1.8% 11.6%

National organisation with

operations in multiple states 72.1% 18.5% 1.0% 8.4%

Multinational organisation with

operations in other countries 78.0% 13.1% 1.3% 7.6%

Over three-quarters (76 per cent) of 457 visa holders help to train or develop other workers. The emphasis on training was echoed by employers, 68.5 per cent of whom said they were using 457 visa holders to train Australian counterparts. For the largest employers, of over 500 people, this rose to 74 per cent. Moreover, 85 per cent of employers listed strong skills in teamwork and people management as an important factor in assessing a potential nomination. Perhaps the most significant indicator of the importance of the program in up-skilling Australia is that nearly four in every five multinational organisations surveyed specified that they use 457 visa holders to train and develop Australian workers. To ameliorate the effect on incentive to

train domestically, benchmarks have been intentionally built into the program design. As discussed previously, employers must either demonstrate that one per cent of the payroll is spent on training their own workers or they must contribute two per cent of the payroll to an industry training fund.

The survey asked both employers and employees a series of questions around training. The results refute previous conceptions of a one-way negative effect on training; the survey shows a positive correlation between temporary migration and the development of human capital.

Graph 4: 457 visa holders training of Australian workers by industry

0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70% 80% 90%

Professional, Scientific

and Technical Services and Safety Public Administration Real Estate Services Rental, Hiring and Retail Trade and Warehousing Transport, Postal Wholesale Trade Total

Other Services

Mining

Manufacturing

Information media and

telecommunications

Health Care and

Social Assistance

Financial and

Insurance Services

Electricity, Gas, Water

and waste Services

Education

and Training

Construction

Arts and Recreation

Services

Agriculture, Forestry

and Fishing

Administrative and

Support Services

Accommodation and

Chapter 4: Temporary migration and the global

economy

Case Study

Almost all of the ASX200 companies use the 457 program. Among the original rationales listed for introducing long-term visas for temporary migrants was to enable global firms to move employees from one country to another. David, a senior HR manager at a

multinational retail firm operating in Australia and over 200 other countries, explains how 457 visa holders have added to his firm.

“We have between 10 to 15 senior executives on 457 visa holders from a total staff

population of over 5000. The vast majority of all recruitment is Australian as we consider the firm to be highly competitive in the labour market.”

“Temporary migration allows these highly experienced managers to hit the ground running. We operate across all regions of the world and through a number of subsidiary firms. They bring knowledge and skills along with a proven, qualified background. This is vital for our business model and when change occurs.”

“Being a multinational firm, the majority of these are ‘internal transfers’, bringing with them an understanding of the firm’s culture, existing manufacturing and sales methods. Being located in Australia is also a major attraction to some.”

David says in very select circumstances, the firm also targets ‘hot spots’. He said recently this occurred with hiring a handful of engineers given competition from the resource industry. However, there are also downsides.

“There are drawbacks for us. The process is expensive and bureaucratic. We use an external migration agent. The firm also wears potential risk under the conditions of the 457 program. This is why we use the program only when necessary and do so judiciously.”

He says that recent changes to short-term business visas have negatively impacted the firm. “These changes now require more temporary, short-term jobs to undertake the 457 visa process. This has really impacted on ancillary services, such as IT support, where short-term jobs are common. Global firms require flexibility with staff movement otherwise inefficiencies and bottlenecks are quickly created where there was none before.”

Chapter 4: Temporary migration and the global

economy

The AWPA’s Future Focus: 2013 National Workforce Development Strategy notes that domestic training alone cannot cater for anticipated demand.25The strategy

acknowledges that significant levels of migration will be needed to supply industry with the qualifications to sustain current growth trajectories. The strategy does not distinguish between permanent and temporary migration and does not comment on the move to a demand-driven model, matching skills supplied and industry need. Moreover, in looking through the prism of formal qualifications, the strategy sees migration only as an input of skills capital. It is recommended that future workforce development strategies examine the role that the flow of temporary skilled workers has in supporting in-house training and the transfer of knowledge.

National innovation system

Indeed, beyond filling predicted demand, the level of training and skill facilitation indicated in the survey raises important questions about the role that the 457

program is playing in supporting our national innovation system.

Human capital accumulation and the movement of people are increasingly being recognised as key determinants of the level of innovation. Australia is handicapped by geographical isolation and a relatively small domestic economy. As 98 per cent of innovation occurs outside of Australia,26

any national innovation strategy must consider how Australia connects with global developments. It is probable that temporary migration and the flow of people has become a critical mechanism allowing Australia to secure a foothold in innovation breakthroughs. The movement of people maintains our link to international evolutions in processes and knowledge frameworks and the diffusion of technology.

25 ibid.

26 Smith, R, Migration and the Innovation Agenda, Department of Innovation, Industry, Science and Research Working Paper, April 2011.

The results paint a compelling and previously unseen picture of the role that the 457 program plays in Australia’s national skills and workforce development strategy. In some industries, migration might be playing the central role in workforce development at the enterprise level. In the accommodation and food services sector, for instance, over 80 per cent of employers said 457 visa holders help training and develop Australians while over 95 per cent of 457 visa holders say they train and develop other workers. Some employers who use the 457 scheme choose to provide training to their Australian workers, with 90 per cent stating they offer training to their employees.

Once here, 79 per cent of 457 visa holders felt they received the same level of training as their Australian counterparts, with only 8 per cent indicating that they received less training than Australian workers. Moreover, an overwhelming majority (86 per cent) of 457 visa holders felt that their job in Australia used their skills and training well. The data discredit previous assumptions that employers do not provide training for 457 visa holders.

Rather than the 457 program simply plugging skills gaps, the data show that the 457

program is working to up-skill our domestic workforce and connect us with global practice. According to modelling developed for the Australian Workforce and Productivity Agency (AWPA), Australia will face a shortage of 2.8 million higher-skilled qualifications by 2025, falling significantly short of industry demand.23 In effect, in the years leading to

2025, demand for qualifications will continue to increase between 3 and 4 per cent each year.24

23 Australian Workforce and Productivity Agency (AWPA) 2013, Future focus: 2013 National Workforce Development Strategy, http://www. awpa.gov.au/our-work/national-workforce-development-strategy/ Pages/default.aspx.

Chapter 4: Temporary migration and the global

economy

Case Study

With economic growth in Asia fuelling Australian exports, Brad, an HR manager at a multi-site Western Australian engineering firm says the 457 program has helped his firm grow to meet demand. The program has also provided unexpected benefits.

With over 350 staff across five locations, the firm has rapidly expanded during the past decade. Back in mid-2011, with iron ore and gold prices at historic highs, the company began a nationwide search for skills. Job advertisements were placed in local papers across multiple states including Tasmania. However only a handful of candidates had suitable skills or were willing to relocate. Additional apprentices and a strong indigenous recruitment program, helped alleviate some of the demand but the firm also decided to recruit skilled migrants through the 457 program. From a recruiting campaign targeting Ireland and the United Kingdom, Brad was able to hire a range of boilermakers, fitters and a couple of carpenters.

Over the past 18 months, these skilled migrants have come to call Australia home. With a no Fly-in, Fly-out policy, these migrants and their families are supporting the local communities and economies of regional Western Australia from Kalgoorlie to Port Hedland. Brad says the firm prides itself on the provision of initial accommodation, social support for spouses and community introductions for schools.

After recruiting about 70 migrants on 457 visas over the last two years, Brad says his firm is now able to focus its recruiting strategy on Australian workers:

“The labour market has changed recently and we’ve been able to find a good number of skilled tradespeople, apprentices and other un-skilled workers to fill our vacancies”. Brad says the most surprising outcome of recruiting migrants was the unique qualities and skills they brought to Australia:

“Some of these guys were working in high tech environments such as nuclear engineering back in the UK and they have completely transformed the way we look at workplace safety. “The guys who have come over have been able to teach the rest of our staff how to improve process and get better outcomes without relaxing safety standards”.

Brad says the firm has started sponsoring those that want to stay in Australia for permanent residency.

In summary Brad said that the overseas recruiting campaign has resulted in a influx of skilled workers who helped fill a need and also provided the company, and the state with workers and their families who will contribute to the economy in the future.