HEI Working Paper No: 04/2004

Inflation Targeting and

Exchange Rate Pass-Through

Alessandro Flamini

Graduate Institute of International Studies

© The Authors.

All rights reserved. No part of this

paper may be reproduced without

In‡ation Targeting and Exchange Rate Pass-through

Alessandro FlaminiyGraduate Institute of International Studies First draft: June 2004

This version: April 2005

Abstract

This paper analyzes how endogenous imperfect exchange rate pass-through a¤ects in‡ation targeting optimal monetary policies in a New Keynesian small open economy. The paper shows that an inverse relation exists between the pass-through and the insulation of the economy from foreign and monetary policy shocks, and that imperfect pass-through tends to decrease the variability of the terms of trade. Furthermore, with CPI in‡ation targeting, in the short run, delayed through constrains monetary policy more than incomplete pass-through and interest rate smoothing ampli…es this e¤ect. When the pass-pass-through decreases, the variability in economic activity tends to raise and the trade-o¤ between the stabilization of CPI in‡ation and output worsens in direct relation to how strictly the central bank is targeting CPI in‡ation. In contrast, with

domestic in‡ation targeting, optimal monetary policy is not constrained and opposite results occur. Consequently, imperfect pass-through favors the choice of domestic to CPI in‡ation targeting.

JEL Classi…cation: E52, E58, F41.

Key Words: In‡ation Targeting; Exchange Rate Pass-through; Small open-economy; Direct Exchange Rate Channel; Optimal Monetary Policy.

1

Introduction

What is the appropriate monetary policy response to domestic and foreign shocks with imperfect exchange rate through? How does incomplete or delayed pass-through a¤ect the e¢ ciency of the monetary policy and the volatility of the economy? What measure of in‡ation should a central bank target considering di¤erent types of pass-through? In the last few years this type of questions has prompted an increase of interest in the relationship between the pass-through of the exchange rate and

This paper has been partly prepared during my visit at Princeton University, January-May 2003 and partly during my stay at the Graduate Institute of International Studies of Geneva. I thank Charles Wyplosz and Lars Svensson for valuable discussions, hindsight and encouragement and an anonymous referee for useful and detailed comments. I thank Hans Genberg, Alexander Swoboda and Michael Woodford for useful discussions and suggestions. I have also bene…ted from comments from Gianluca Benigno, Andrea Fracasso and Roman Marimon and the participants to seminars at the Graduate Institute of International Studies, the London School of Economics, the Ente Einaudi, and the XIII international ”Tor Vergata” conference on Banking and Finance. Any errors are my own. Financial support from Ente ‘Luigi Einaudi’and Princeton University is gratefully acknowledged.

the working of the economy1. This interest is supported by several empirical works spanning over two decades and di¤ering for the countries and the industries considered which provide evidence on imperfect pass-through2.

The pass-through of costs to import price is a complex mechanism, and several factors may play a role in its determination. The positive correlation between in‡a-tion and in‡ain‡a-tion persistence, and the positive impact of the expectain‡a-tions of in‡ain‡a-tion persistence on the pass-through (via the Taylor staggered price-setting behavior), es-tablish a positive relation from in‡ation to the degree of pass-through (Taylor, 2000). Also, the …rm’s strategy of the pricing to market (PTM) based on international mar-ket segmentation and local currency pricing (LCP) leads to incomplete pass-through (Betts and Devereux, 2000).3 Furthermore, the presence of shipping costs and non-traded distribution services as well as intermediary …rms between the exporters and the consumers is likely to reduce the pass-through more (Mc Callum and Nelson (1999), Obstfeld and Rogo¤ (2000)).

Taking these factors into account, it has been possible to obtain interesting results on the relation between the pass-through and the optimal monetary policy4.

In a New Keynesian perspective, considering an emerging market economy with nominal rigidities in both the non-traded goods and import sectors, Devereux, Lane and Xu (2004) show that in the case of complete pass-through, non-tradable in‡ation-targeting dominates CPI in‡ation-in‡ation-targeting and an exchange rate peg while, in the case of delayed pass-through, CPI in‡ation-targeting performs better. Devereux (2001) considers a small open-economy with sticky prices in the non-traded goods and import sectors and compares the Taylor rule, a rule that stabilizes non-traded goods in‡ation, strict CPI in‡ation-targeting and a rule which pegs the exchange rate. He …nds that in general, with delayed pass-through, the trade-o¤ between output and in‡ation variability is less pronounced; the best monetary policy sta-bilizes non-traded goods price in‡ation; and strict CPI in‡ation-targeting performs better with partial pass-through. Smets and Wouters (2002) present a small open-economy model calibrated to euro area data with nominal rigidities in the domestic and imported goods sectors. In this framework, they consider that the welfare costs determined by nominal rigidities in the imported goods sector depend positively on the exchange rate variability. Consequently, they make the point that with delayed pass-through, output-gap stabilization is constrained by the minimization of these

1

The expression ”exchange rate pass-through” denotes the transmission of a change in import costs to the domestic prices of imported goods.

2

For example, Krugman (1987) considering US import data in the period 1980-1983 …nds that, in the machinery and transport sector, 35 to 40 percent of the appreciation of the dollar was not re‡ected in a decrease of the import prices. Knetter (1989) …nds that for the period 1977-1985 US export prices in the destination market currency tend to be either insensitive to exchange rate ‡uc-tuations or tend to amplify their impact, while German export prices tend to stabilize the exchange rate ‡uctuations. Considering the sample period 1974-1987, Knetter (1993) shows that Japanese export price adjustments in the destination country currency o¤set 48 percent of the exchange rate ‡uctuations while for U.K. and German export prices this fraction reaches 36 percent. More recently, Campa and Goldberg’s (2002) estimation for the period 1975-1999 and a sample of OECD countries supported the complete pass-through hypothesis for the long run but not for the short run.

3LCP, in turn, has been justi…ed in two ways: by a low market share of the exporter country in

the foreign market coupled with a low degree of di¤erentiation of its goods (Bacchetta and Wincoop, 2002) and by a greater monetary policy stability of the importing country compared to that of the exporting country (Devereux and Engel, 2001 and Devereux et al., 2004).

4

See also Lane and Ganelli (2002) for a survey of the implications of di¤erent degrees of pass-through when the currency denomination of assets contracts is taken into account.

welfare costs because it leads to larger exchange rate variability.

In a New Classical perspective, Corsetti and Pesenti (2004) show the importance of the degree of pass-through in a¤ecting the trade-o¤ between output-gap stabiliza-tion and import costs, and the implicastabiliza-tion for the optimal monetary policy. When the pass-through is incomplete because of LCP, exporters’ pro…ts oscillate with the ex-change rate, and the hedging behavior of the exporters consequently links the import prices positively to the variability of the exchange rate. Then, if the monetary policy aims to stabilize the output-gap, it will increase the variability of the exchange rate and the import prices. Hence, optimal monetary policy has to equate at the margin the cost of the output-gap with the cost of a higher import price. It follows that the lower the pass-through, the lower the socially optimal output-gap stabilization5.

These models employ a welfare optimization approach to determine the monetary policy while considering either delayed or incomplete pass-through. The present study di¤ers from the previous models because embeds into the New Keynesian framework (i) in‡ation-forecast targeting, which is the procedure followed by in‡ation-targeting central banks6; (ii) a more sophisticated transmission mechanism with stylized

real-istic lags for various channels; and (iii) both incomplete and delayed pass-through. All these features are critical to analyze real world monetary policy. As noted by Svensson (2003, 2005), a maximizing welfare approach is not operational, in contrast to in‡ation-targeting. Also, a realistic transmission mechanism is important because it allows addressing a main di¢ culty of monetary policy: the large gap between goals and instrument. Finally, considering only one type of imperfect pass-through could be misleading in the understanding of the transmission mechanism and the actual latitude of the monetary policy.

The motivating idea of this work is that the type and degree of pass-through a¤ects the projections of the economy, whose accurate determination is crucial for central banks that pursue in‡ation-targeting. The reasoning is the following. Optimal mone-tary policy employs all its transmission channels according to their relative e¢ ciency. These channels feature di¤erent transmission lags, however, in open economies one particular channel is considered to have no lag, whence comes the name of Direct Exchange Rate Channel (henceforth DERC). Due to this quality, the DERC allows monetary policy to a¤ect current CPI in‡ation and according to the conventional view, and as it is shown in Ball (1998) and Svensson (2000), this channel plays a prominent role in the transmission of monetary policy. Yet, the DERC is considered in these papers with the strict assumption of perfect pass-through. Since imperfect pass-through a¤ects the e¢ ciency of the DERC and its interaction with the other channels, it a¤ects also the optimal use of all the transmission channels. Thus, the type and degree of pass-through a¤ects the dynamics of the economy and the pro-jections of the macrovariables, which in turn are crucial with the in‡ation-forecast targeting procedure.

The main purpose of this study is to build a simple but reasonably general model

5On the relationship between welfare, exchange rate volatility and incomplete pass-through in a

similar perspective, see also Sutherland (2005).

6The procedure of in‡ation-forecast targeting consists of …rst determining the projections for

in‡ation (and output) conditional to all the information available and the monetary policy, and then chosing the monetary policy that allows the projections to be equal to the targets at a certain time horizon, or more realistically, that determines a desired path for the projections. See Svensson (1997) and (1998b).

to compare di¤erent in‡ation-targeting monetary policies and related responses of the economy to shocks with endogenous incomplete and/or delayed pass-through. The analysis is based on a dynamic stochastic general equilibrium model built upon Svensson’s (2000) model.

This model deviates from Svensson’s (2000) in two ways. 1. It provides com-plete microfoundations, in particular concerning inertia in the aggregate supply and demand relations following Christiano et al. (2001) and Abel (1990), respectively. 2. It includes two interacting sectors: a domestic sector that produces and retails domestic goods and an import sector which only retails foreign goods. These sectors are connected because the domestic one uses as intermediate goods its own goods and the import goods while the import sector uses foreign and domestic goods.

The latter sector is similar to the import sector in Smets and Wouters (2002) in that it derivesdelayed pass-through from the sticky price assumption modeled in the style of Calvo (1983). It is also similar to McCallum and Nelson (1999), Burstein, Neves and Rebelo (2003) and Corsetti and Dedola (2004), in that local inputs may be required to bring the foreign goods to domestic consumers; as a result, when this is the case, foreign goods are intermediate goods in the production of the import goods and the pass-through turns out to be incomplete.

This is a notable feature of the model because it allows us to consider either foreign goods as intermediate goods in the domestic sector but …nal goods in the import sector or asintermediate goods in both the domestic and import sectors. An interest in the latter case is motivated by the …nding of Kara and Nelson (2002), who show that modelling imports as intermediate goods leads to an aggregate supply which delivers the best approximation of the exchange rate/consumer price relationship.

Such ‡exibility in the degree of delay and completeness of the pass-through allows a better understanding of the relation between the various exchange rate channels and the transmission mechanism of the monetary policy. Speci…cally, it illustrates how the pass-through a¤ects the optimal use of all the transmission channels.

A key feature of this model is that it derives structural relations for all the agents in the economy. In particular, the central bank follows a speci…ctargeting rule which, as it has been shown by Svensson (2003), is equivalent to the equilibrium condi-tion equating the marginal rate of substitucondi-tion and transformacondi-tion between the loss function variables. The model determines this rule assuming that the central bank minimizes in each period its intertemporal loss function under discretion, i.e. taking the expectations of the private sector as given and knowing that it will reoptimize in the subsequent periods. Thus the model looks for the Nash equilibrium in the game between the central bank and the private sector, which turns out to be characterized by a time-invariant reaction function for the central bank.

Within this framework the present study addresses some issues that have been neglected in the literature. First, it analyzes the way in which the pass-through a¤ects the working of the DERC and examines to what extent this latter channel is reliable for the transmission of the monetary impulse in the short run. Such an analysis is important, as this channel is considered to be the only one available to stabilize CPI in‡ation in the short run.

Second, it considers that the DERC is also one of the avenues through which shocks originating in the foreign sector propagate to CPI in‡ation. Indeed, a shock in foreign output or in‡ation a¤ects the foreign interest rate, which in turn propagates to the exchange rate via the interest rate parity condition, …nally hitting CPI in‡ation.

Thus, the second question addressed is how the way in which the pass-through occurs a¤ects the degree of insulation of the economy from foreign shocks.

Third, the paper investigates the impact of imperfect pass-through on the volatil-ity of the economy and on the choice of the in‡ation target.

With regard to in‡ation-targeting e¤ectiveness, the analysis shows that the type and degree of imperfect pass-through a¤ect the capacity of the central bank to sta-bilize in the short run CPI in‡ation but not domestic in‡ation. More speci…cally, delayed pass-through turns out to reduce monetary policy e¤ectiveness more than in-complete pass-through. Yet, similarly to domestic in‡ation-targeting, in the medium run, imperfect pass-through constrains less CPI in‡ation-targeting.

In relation to the volatility of the economy, this study indicates that imperfect pass-through decreases the variability of the terms of trade and, with CPI in‡ation-targeting, tends to increase the variability of the economy. Consequently, this study suggests that it may be better to target domestic in‡ation with incomplete and de-layed pass-through.

The model also shows that, with CPI in‡ation-targeting, imperfect pass-through increases the trade-o¤ between CPI in‡ation and output-gap variabilities, and that this phenomenon is stronger the more monetary policy is concerned with CPI in‡ation versus output-gap stabilization. Thus, it is important to know the type and degree of the pass-through to assess the attainable trade-o¤ between the variability of the output-gap and CPI in‡ation.

Finally, interest smoothing constrains the ability of the central bank to stabilize CPI and domestic in‡ation in the short run.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows: section 2 presents the model. Section 3 analyzes the optimal monetary policy; in particular, the reaction functions corresponding to di¤erent types of in‡ation-targeting and pass-through and the im-pulse response functions to some domestic and foreign shocks. Section 4 focuses on the relation between the pass-through, the volatility of the economy and the choice of the in‡ation measure to target. Section 5 concludes and suggests some directions for further research. Appendix A and B present some details of the microfoundations of the model and its state-space form.

2

The model

The model describes a small open economy related to an exogenous rest of the world. All the equations for the domestic economy are structural relations derived from equilibrium conditions that characterize optimal private and public sector behaviors. In order to focus the analysis on the main features of the monetary transmission mechanism, I follow Woodford (2003) in considering a “cashless” economy7.

2.1 The household

The economy is populated by a continuum of unit mass of consumers/producers indexed by j 2 [0;1]sharing the same preferences and living forever. Intertemporal utility for the representative agent is given by

7

Woodford (2003) shows that, in general, abstracting from monetary frictions has a minor impact on the working of the economy.

Et

1 X

=0

U Ct+ ; Ct+ 1 ; (1)

where is the intertemporal discount factor, Ct is total consumption of consumer

j; and Ct is the total aggregate consumption. Preferences over total consumption

feature habit formation which is modeled in the style of Abel (1990) by the following instantaneous utility function

U Ct+ ; Ct+ 1 = 8 > > < > > : (Ct+ =Cte+ 1) 1 1 1 1 6= 1 ln Ct+ =Cte+ 1 = 1 9 > > = > > ; ;

where e 0captures the willingness to “keep up with the Joneses” and >0 is the intertemporal elasticity of substitution. This assumption is motivated by the results of Fuhrer (2000) and Banerjee and Batini (2003) which show the importance of habit formation in explaining the inertia in consumption decisions, consequently improving the empirical …t of the sticky prices open economy model.

For sake of simplicity, labor is absent from the preferences of the consumer/producer captured by (1)8. Yet, as it will be shown later, production implies disutility for the

consumer in the form of less consumption available. Indeed, consumption goods are also intermediate goods used in production. Furthermore, since the input require-ment function is convex9, more production implies a smaller share of goods available

for consumption. Thus, the utility function (1) can be interpreted as the utility of the yeoman farmer which is increasing and concave in consumption and decreasing and convex in production.

Total consumption,Ct; is a CES aggregate of two subindices for consumption of

the domestic good,Ctd;and import good,Cti;

Ct (1 w)Cd 1 1 t +wC i1 1 t 1 ; (2)

where is the intratemporal elasticity of substitution between domestic and import goods and it is assumed equal to one following Corsetti and Pesenti (2004)10, w

determines the steady state share of imported goods in total consumption and Ctd,

Cti are Dixit-Stiglitz aggregates of continuum of di¤erentiated domestic goods and import goods (henceforth indexed with dand irespectively),

Cth = Z Cth(j) 1 1 # dj 1 1 # ; h=d; i;

where # > 1 is the elasticity of substitution between any two di¤erentiated goods and, for sake of simplicity, is the same in both sectors.

The ‡ow budget constraint for consumerj in any period tis given by

Bt 1 +It + Bt 1 +ItSt+P c tCt=Bt 1+Bt 1St+Ddt +Dti;

8Another example of similar preferences is in Svensson (2000). 9

The input requirement function is convex because the production function is assumed to be concave. This assumption, in turn, can be motivated by constant capital.

where B and B are two international bonds issued on a discount basis and denomi-nated in domestic and foreign currency with interest ratesItandIt respectively,Stis

the nominal exchange rate, expressed as home currency per unit of foreign currency.

Ddt andDit are the dividends distributed by the domestic and the import sector and, …nally,Pc is the overall Dixit-Stiglitz price index for the minimum cost of a unit of

Ct and is given by

Ptc=h(1 w)Ptd(1 ) +wPti(1 )i

1 1

; (3)

with Pd; Pi denoting, respectively, the Dixit-Stiglitz price index for goods produced in the domestic and import sector.

To rule out “Ponzi schemes”, I assume that in any periodtthe consumer chooses the value of the portfolio int+ 1such that his borrowing is no larger than the present value of all future dividends

Bt+1+Bt+1St+1

1 X

T=t+1

(1 +IT) 1 DdT +DTi ;

and that the present value of future dividends is …nite.

Utility maximization subject to the budget constraint and the limit on borrowing gives the Euler equation and the uncovered interest rate parity, respectively

ct= ct 1+ (1 )ct+1jt (1 ) it tc+1jt ;

e(1 )

1 +e(1 ) <1; (4)

it it =st+1jt st; (5)

where for any variable x;the expressionxt+ jtstands for the rational expectation of

that variable in periodt+ conditional on the information available in periodtand, by means of a log-linearization, the variables ct, tc, it, it and st+1jt st are

log-deviations from their respective constant steady state values; …nally, ctdenotes total

aggregate consumption, obtained considering that in equilibrium total consumption for agentj is equal to total aggregate consumption, i.e. Ct=Ct;and ct denotes CPI

in‡ation (measured as the log deviation of gross CPI in‡ation from the constant CPI in‡ation target).

2.1.1 Domestic consumption of goods produced in the domestic sector

Preferences captured by equation (2) imply that the (log deviation of the) domestic demand for goods produced in the domestic sector, cdt;is given by

cdt =ct pdt pct ;

which, considering the (log-linearized version of the) price index equation (3), can be rewritten as

cdt =ct+w qt; (6)

where qt pit pdt is the terms of trade.

Then, solving equation (4) forctand combining it with equation (6) I obtain

whereF1 <1is the smaller root of the characteristic polynomial of equation (4) and t 1 X =0 it+ jt td+ +1jt (8)

can be interpreted as the long real interest rate11 12:

2.1.2 Aggregate demand for goods produced in the domestic sector

Total aggregate demand for the good produced in the domestic sector is b

Ytd=Ctd+Ytd;d+Ytd;i+Ctd; (9) whereYtd;d; Ytd;iandCtddenote the quantity of the (composite) domestic good which is used as an input in the domestic sector, as an input in the import sector and which is demanded by the foreign sector, respectively.

To specify the quantities of the (composite) domestic good which are used as an input in the domestic and import sector, it is convenient to describe here the pro-duction technologies. I assume that both sectors share the same Leontief technology and each one features a continuum of unit mass of …rms, indexed by j; that produce di¤erentiated goods Ytd(j)andYti(j)in the domestic and import sector respectively. Furthermore, I assume that sectors di¤er for the input used: the domestic sector uses a composite input consisting of the domestic (composite) good itself and the (compos-ite) import good produced in the import sector; the import sector uses a composite input consisting of the foreign good Yt and the domestic (composite good). Thus the production functions in the domestic and import sector are given respectively by

Ytd(j) =f " Adtmin ( Ytd;d 1 ; Yti;d)# ; Yti(j) =f " Aitmin ( Yt 1 i; Ytd;i i )# ; (10) where f is an increasing, concave, isoelastic function, At is an exogenous (sector

speci…c) economy-wide productivity parameter, ; i 2[0;1]; (1 ) and denote,

respectively, the shares of domestic good and import good in the composite input required to produce the di¤erentiated domestic good j; and 1 i and idenote, respectively, the shares of foreign good and domestic good in the composite input required to produce the di¤erentiated import good j:

Thus the quantities of the (composite) domestic good used as an input in the domestic and import sector are

Ytd;d= 1 Adt (1 )f 1 Ybd t ; (11) Ytd;i = 1 Ait if 1 Ybi t ; (12) where Ybi

t denotes the demand of the import good. Finally, log-linearizing equation

(9) around the steady state values yields

1 1Under the expectations hypothesis and considering a zero-coupon bond with a …nite maturity,

the variable t is approximately the product of the long real bond rate and its maturity; for further discussion see Svensson (2000).

b

ytd= 1 i cdt + 2 i ybti+ 3 i ctd; (13)

where 0

1 i ; 03 i <0and 02 i >0;(see the appendix for details):

Next, I assume, as in Svensson (2000), thatctdis exogenous and given by

ctd=ct + w qt

= yyt + w qt; (14)

where ct denotes (log) foreign real consumption, and w denote, respectively, the foreign atemporal elasticity of substitution between domestic and foreign goods and the share of domestic goods in foreign consumption. Furthermore, I de…ne the output-gap in the domestic sector yd

t as

ytd bydt yd;nt ;

where yd;nt denotes the log deviation of the natural output in the domestic sector from its steady state value, and I assume that in both sectors the log-deviation of the natural output from its steady state value is exogenous, stochastic and follows

yth;n+1= yh;nyth;n+ th;n+1; 0 yh;n<1; h=d; i;

where th;n+1 is a serially uncorrelated zero-mean shock to the natural output level. Fi-nally, in line with the central banks’view of the approximate one-period lag necessary to a¤ect aggregate demand, I assume that consumption decisions are predetermined one period in advance and obtain the aggregate demand in the domestic sector in terms of the output-gap

ydt+1 = yydt t+1jt+ qqt+1jt q 1qt+ y yt + ynytd;n+ td+1 d;n

t+1 (15)

where dt+1 is a serially uncorrelated zeromean demand shock. In (15) all the coe¢ -cients are positive and functions of the structural parameters of the model.

2.1.3 Consumption and aggregate demand of goods produced in the

im-port sector

Considering equation (2), the (log-deviation of) consumption of goods produced in the import sector, cit;is given by

cit=ct pit pct

=ct (1 w)qt; (16)

and following the same derivation used for the AD in the domestic sector yields

cit= (1 F1L) 1 t (1 F1L) 1wqt (1 w)qt: (17)

Aggregate demand for import goods is given by b

where Yti;d denotes the amount of the import good used as an input in the domestic sector. Considering the technology in (10), this quantity is given by

Yti;d = 1

Adtf

1 Ybd t :

Log-linearizing (18) around the steady state results in b

yti= (1 e)cit+ebydt: (19) Finally, the same assumptions used to derive the aggregate demand for the domestic sector goods yield

yti+1 = yyit i t+1jt qiqt+1jt+ qi 1qt+

i

y yt + iynyti;n+ dt+1 td;n+1; (20)

where all the coe¢ cients are positive and depend on the structural parameters of the model and ti+1 is a serially uncorrelated zero-mean demand shock.

Summing up, aggregate demands in both sectors in period t+ 1 are based on the information available in period t; because of the assumption of predetermined expenditure decisions. Due to the use of the output produced in the other sec-tor as an input, they depend also on the demand in the other secsec-tor. Due to the assumptions of habit formation in consumption, they depend on the previous aggre-gate demands13. Furthermore, by setting the sequence of expected short nominal interest rates, i.e. it+ jt 1

=0; the central bank a¤ects the long interest rate de…ned

in equation (8) which, in turn, a¤ects the output gap. This is the aggregate de-mand channel. Finally, a …rst exchange rate channel, which consists of switching the demand between domestic and foreign goods, is captured here by the terms of trade.

2.2 Firms

In both sectors, aggregate supply is derived according to the Calvo (1983) staggered price model and in‡ation inertia is introduced as indicated by Christiano et al. (2001) and also by the presence of the terms of trade. Beyond the use of di¤erent inputs, the two sectors have di¤erent …rm decision timing.

2.2.1 Domestic sector

In the domestic sector, the representative consumer/producer j produces the variety

j of the domestic good, Ytd(j);with a composite input whose price is Wt. Since all

the varieties use the same technology, there is a unique input requirement function for all j given by A1d

t

f 1 Ytd(j) and the variable cost of producing the quantity

Yd

t (j) isWtA1d t

f 1 Yd

t (j) :Furthermore, since there is a Dixit-Stiglitz aggregate of

domestic goods, the demand for variety j is

Ytd(j) =Ybtd P d t (j) Pd t # ; 1 3

As it has been noted by Benigno (2004), the presence of the terms of trade introduces furter inertia. Indeed, from the de…nition of the terms of trade it follows that

qt+ jt=qt+ 1jt+ ti+ jt d

where Ptd(j) is the nominal price for varietyj and #is the elasticity of substitution between di¤erent varieties. As shown in equation (10), the composite input is a convex combination of both aggregates of domestic and import goods (with price

Pti and which will be described below). Thus the price of the input is given by

Wt (1 )Ptd+ Pti:

Then, I assume (i) that the consumer/producer chooses in any period the new price with probability (1 ) or keeps the previous period price indexed to past in‡ation with probability ;and (ii) that the price at periodt+gis chosengperiods in advance. It follows that the decision problem for …rm j at timetis

max e Pd t+g Et 1 X =0 ed t+ +g 8 > > > > < > > > > : e Ptd+g P d t+ +g 1 Pd t+g 1 Ptd+g+ Yb d t+ +g 2 6 6 6 4 e Ptd+g P d t+ +g 1 Pd t+g 1 Ptd+g+ 3 7 7 7 5 # Wt+ +g Ptd+ +g f 1 2 6 6 4Ybtd+ +g 0 B B @ e Pd t+g P dt+ +g 1 P d t+g 1 ! Pd t+g+ 1 C C A #3 7 7 5 At+ +g 9 > > > > > > > > > > > = > > > > > > > > > > > ; ; where ed

t; Petd+g and denote, respectively, the marginal utility of domestic goods,

the new price chosen in period tfor period t+g and the degree of indexation to the previous period in‡ation rate14. Following Svensson (2000), I set = 1 to ensure the natural-rate hypothesis. Finally, assuming that the purchasing power parity holds in the long run, the log-linearized version of the Phillips curve for the domestic sector turns out to be d t+2= 1 1 + " d t+1+ dt+3jt+ (1 )2 (1 +!#) !y d t+2jt+ qt+2jt # +"t+2; (21)

where ! is the output elasticity of the marginal input requirement function and"t+2

is a zero-mean i.i.d. cost-push shock.

In line with the central banks’ experience of an approximate two-period lag re-quired to a¤ect domestic in‡ation, I derive (21) assuming that pricing decisions are predetermined two periods in advance, i.e. g = 2: Equation (21) is equal to the Svensson (2000) aggregate supply, except (i) for the inertia in the in‡ation dynamics, which is here also based on the indexation to past in‡ation and (ii) for the charac-terization of import goods, which in this model are generally di¤erent from foreign

1 4

Recalling that consumption decisions are predetermined one period in advance, the marginal utility of domestic goods ed

t is obtained by the following …rst-order condition with respect toCtd+1

EtUd Ctd+1; Cti+1 =Et

h

t+1Ptd+1

i

Etedt+1;

goods15.

According to (21), in‡ation is a predetermined variable based, on the one hand, on expectations of future in‡ation, demand and input price relying on the information set available two periods ago. On the other hand, it is based on previous value of in‡ation. It is worth noting that the relevance of the assumptions of (i) predetermined pricing decision and (ii) indexation to the previous period in‡ation is in improving the empirical …t. Indeed, as shown by Woodford (2003), these assumptions eliminate two counterfactual predictions of the basic Calvo model, i.e. the immediate and sharp reaction of in‡ation to monetary policy shocks.

Equation (21) shows that beyond the aggregate demand and the in‡ation expec-tations channels, monetary policy a¤ects domestic in‡ation via the impact of the nominal exchange rate on the real price of the input, which turns out to be equal to

qt16:This is thesecond of the three exchange rate channels embedded in this model.

The strength of this channel depends on nominal rigidities, imperfect competition and the (degree of) convexity of the input required function captured, respectively, by ,

# and !:Also, it depends on the relevance of the import goods in the production of the domestic goods, which is captured by , and, indirectly, on the characteristics of the pass-through17.

2.2.2 Import sector

Similarly to the domestic sector, variety j of the import goods, Yti(j), is produced by the representative consumer/producerj with a composite input whose price isFt.

Since the input requirement function is A1i t

f 1 Yti(j) ;the variable cost of producing the quantity Yti(j) is FtA1i

t

f 1 Yti(j) . Furthermore, since there is a Dixit-Stiglitz aggregate of import goods with elasticity of substitution # > 1; the demand for variety j is Yti(j) =Ybti P i t(j) Pi t # ;

wherePti(j)is the nominal price for varietyj;andPti is the Dixit-Stiglitz price index for import goods. Finally, considering that the input is a convex combination of the aggregate of domestic goods and of the foreign good, with pricePtSt;wherePt is the

price in foreign currency of the foreign good, it follows thatFt iPtd+ 1 i PtSt.

Now relaxing the assumption that pricing decisions are predetermined g periods

1 5

Here import and foreign goods coincide in the special case of complete pass-through, which is described below.

1 6Indeed, log-linearizing the real price of the composite input Wt

Pd t

around the steady state yields

qt:

1 7

As it will be shown below, the terms of trade qt depend on the price level in the import sector, which in turn depends on the pass-through.

in advance, the problem of the consumer/producer j is max e Pi t Et 1 X =0 ei t+ 8 > > < > > : e Pi t Pti+ 1 Pi t 1 Pti+ Yb i t+ 0 B @ e Pi t Pti+ 1 Pi t 1 Pti+ 1 C A # Ft+ Pti+ f 1 2 6 6 4Ybti+ 0 B @ e Pi t P it+ 1 P it 1 Pi t+ 1 C A #3 7 7 5 At+ 9 > > > > > > > > > > = > > > > > > > > > > ; ;

where Peti, eit; i have the same meaning of their analogous variables in the domestic sector. Here, the assumption ofg= 0 is motivated by the fact that the import sector acts as a retailer sector for the foreign goods and, in practice, retailers do not set their price before they take e¤ect as much as producers do.

Then, assuming = 1 and that the purchasing power parity holds in the long run, the log-linearized version of the Phillips curve in the import sector is given by

i t= 1 1 + " i t 1+ ti+1jt+ 1 i 2 i(1 +!#) !y i t+qti # ; (22) whereqti denotes (the log deviation of) the price of the composite input in the import sector expressed in terms of the import goods price, pi

t;and is de…ned as

qti 1 i (st+pt) + ipdt pit; (23)

where pt is the (log) foreign price level. It is worth noting that the introduction of the variableqti is a convenient way to obtain an aggregate supply relation in terms of stationary variables.

Equation (22) is derived in a similar way to (21). Here, however, pricing decisions are no longer assumed to be predetermined. As a result, ti is a forward looking variable and we have a direct in‡ation expectation channel working via ti+1jt and a

third exchange rate channel working viaqi;the DERC18. To describe incomplete pass-through, it is worth recalling that production in the import sector uses foreign goods and the goods produced in the domestic sector. The need of distribution services motivates the presence of the goods produced in the domestic sector. Speci…cally, it is assumed that to bring one unit of the foreign good to domestic consumers requires some units of a basket of di¤erentiated domestic goods. Consequently, by introducing a wedge between the price of the foreign goods paid by the domestic consumers and by

1 8

It is interesting to note that part of the direct expectation channel adds to the DERC. Indeed, equation (22) can be solved forward to obtain

i t= i t 1+ 1 i 2 i(1 +!#) 1 X =0 !yit+ jt+q i t+ jt ;

which shows that the DERC works not only viaqi

tbut also via all the sequence ofqti;i.e. qti+ jt

1

the retailers, this assumption models thedegree of completeness of the pass-through. In particular, it establishes an inverse relation between the completeness of the pass-through and the need of distribution services captured by the coe¢ cient i:

A notable feature of this Phillips curve is that the stickiness in the price adjust-ment determines the speed of the pass-through. When i = 0; all the …rms in the import sector set in any period their price equal to a mark-up over the marginal cost. Thus a shock to the exchange rate or the foreign price feeds immediately to the price of the import goods. In addition, if we assume also no local inputs, ( i = 0); we obtain the benchmark case of perfect (i.e. complete and immediate) pass-through where the DERC reaches its greatest e¢ ciency.

2.2.3 CPI in‡ation

Considering the log-linearized version of the CPI price equation (3), CPI-in‡ation,

c

t;is given by

c

t = (1 w) td+w it: (24)

Since dt is predetermined, at time t monetary policy can a¤ect ct only with it:

Speci…cally, since yi

t is predetermined as well, monetary policy a¤ects tc by steering

the nominal exchange rate which is a forward looking variable given the uncovered interest parity (always ful…lled) and the purchasing power parity (ful…lled only in the long run). Then, monetary policy a¤ects i

t according to the Phillips curve (22) via

the impact of the exchange rate on the real price of the input in the import sector illustrated by equation (23) and via ti+1jt:This indicates the role of the DERC and expectations in allowing monetary policy to have an impact on CPI in‡ation in the short run.

2.3 Uncovered interest parity in terms of qi; transmission channels

and lags

In order to eliminate the non-stationary nominal exchange rate, it is convenient to express the UIRP in terms of qti obtaining

qit+1jt qit= 1 i rt 1 i it t+1jt

i t+1jt

d

t+1jt ; (25)

where rt is the short term real interest rate de…ned asrt it td+1jt:

Summing up, almost all channels need some time to convey the monetary policy to in‡ation. With the aggregate demand channel there is a (one-period) lag to transmit the stimulus to CPI in‡ation via the output-gap in the import sector, and a (two-period) lag to a¤ect domestic in‡ation via the expected output-gap in the domestic sector19. With both the in‡ation expectations channel and with the channel that transmits the impact of the exchange rate to the price of the input in the domestic sector, i.e. qt+2jt in equation (21), there is a (two-period) lag to a¤ect domestic

in‡ation due to predetermined price setting behavior. The only channels for which there is no lag are the direct in‡ation expectation channel and the DERC. For the latter, the real interest parity condition (25) conveys the monetary impulse to the real price of the composite input in the import sector, qti, which, in turn, directly hits import sector in‡ation.

1 9

It is a common assumption in the literature that the aggregate demand channel a¤ects in‡ation with a two-period lag.

2.4 The public sector

The behavior of the central bank consists of minimizing the following loss function

Et 1 X =0 h c c2 t+ + d dt+2 + ytd+2 + (it+ it+ 1)2 i ; (26)

where d; i; and are weights that express the preferences of the central bank for the CPI and domestic in‡ation targets, the output stabilization target and the instrument smoothing target respectively.

2.5 The rest of the world

I assume stationary univariate AR(1) processes for the exogenous variables foreign in‡ation and income

t+1 = t +"t+1; (27)

yt+1 = yyt + t+1; (28) where the coe¢ cients are non-negative and less than unity and the shocks are white noises. Finally, the foreign sector sets the monetary policy according to the following Taylor rule

it =f t +fyyt + it; (29) where the coe¢ cients are positive and it is a white noise.

2.6 Calibration

The choice of the structural parameters mostly follows Svensson (2000). See the Appendix for the full set of parameters.

3

Optimal monetary policy

To recap, the model consists of the maximization of the central bank, …rms and households preferences and their optimal behaviors are described by structural rela-tions, namely the reaction function for the central bank, the aggregate supplies for the …rms and the aggregate demands for the households.

In this general equilibrium model, the (column) vectors of predetermined20, forward-looking variables and innovations to the predetermined variables are, respectively,

Xt= dt; dt+1jt; it 1; t; ydt; yti; yt; it; y d;n t ; y i;n t ; it 1qt 1; qti 1 0 ; xt= it; qti; t; dt+2jt 0 : t= "t; "t; 0; "t; dt d;n t ; it i;n t ; t; f "t +fy t + i;t; d;n t ; i;n t ; 0; 0; 0 0 : 2 0

It is worthwhile pointing out that td+1jt is a predetermined variable. This is apparent if we consider the domestic sector Phillips curve and take the expectation at timet+1because"t+2jt+1= 0

and d

In this model the rational expectations equilibrium is the set of plans n it+ jt; td+ jt; i t+ jt; y d t+ jt; y i t+ jt; qt+ jt; qit+ jt o1 =0

such that, for any given vector of the shocks and set of plans for the exogenous variables, (i) the central bank maximizes its preferences, (ii) the households maximize their utilities and (iii) the …rms maximize their pro…ts. Since each agent takes the (optimal) behavior of the other agents as given in his decision process, these plans are also a Nash equilibrium.

Intuitively, the central bank chooses the instrument-rate plan it+ jt 1=0 that,

given the lags in transmission channels, determines expectations of future in‡ation and output with the smallest variability and in line with their targets at a certain time horizon. Thus, the more forward looking the private sector behavior, the more monetary policy consists of the management of the expectations.

Concerning the optimal monetary policy, the model presents a time-invariant reaction function which is the …rst order condition obtained by the intertemporal optimization of the central bank preferences. This function is linear in the vector of the predetermined variables and since the model is linear-quadratic and uncertainty enters additively, certainty equivalence holds and it does not depend on the covariance matrix of the shocks. To …nd this reaction function I used the dynamic programming technique of the linear stochastic regulator with rational expectations and forward-looking variables21.

3.1 Domestic and CPI in‡ation-targeting

Table 1 and 2 report the coe¢ cients of the reaction functions for the cases of strict and ‡exible domestic and CPI in‡ation-targeting under various assumptions on the types and degree of pass-through22.

Table 1. Domestic in‡ation-targeting, reaction-function coe¢ cients

Strict dom. dt dt+1jt ti 1 t ytd yti yt it ytd;n yi;nt it 1 qt 1 qti 1

Perf.; i=0; i=0:05 0.00 1.49 0.00 0.08 0.08 -0.00 0.07 -0.02 -0.07 -0.02 0.52 0.00 0.00

Inc.; i=0:5; i=0:05 0.00 1.54 0.00 0.03 0.09 -0.01 0.04 -0.01 -0.08 -0.01 0.51 0.00 0.00

Del.; i=0; i=0:5 -0.01 1.49 0.03 0.08 0.08 0.02 0.09 0.01 -0.08 0.00 0.48 0.01 0.00 Del., Inc.; i=0:5; i=0:5 0.00 1.53 0.02 0.03 0.09 0.01 0.05 0.00 -0.09 0.00 0.50 0.00 0.00

Flexible dom. dt dt+1jt ti 1 t ytd yit yt it ytd;n yti;n it 1 qt 1 qit 1

Perf.; i=0; i=0:05 0.03 0.74 0.00 0.28 0.68 0.02 0.18 -0.06 -0.05 -0.02 0.37 -0.03 0.00

Inc.; i=0:5; i=0:05 0.02 0.76 0.00 0.08 0.71 -0.01 0.07 -0.03 -0.09 -0.03 0.38 -0.02 0.00

Del.; i=0; i=0:5 -0.02 0.74 0.06 0.10 0.70 0.03 0.12 0.02 -0.11 -0.00 0.36 0.02 0.00

Del., Inc.; i=0:5; i=0:5 0.01 0.75 0.03 0.06 0.71 0.02 0.07 0.00 -0.11 -0.01 0.37 -0.01 0.00

2 1

In particular, since this optimization problem does not have a closed form solution, I used the Oudiz and Sachs (1985) algorithm, which is further discussed in Backus Dri¢ l (1986), Curie and Levine (1993) and Soderlind (1999). The optimization problem is reported in Appendix B.

2 2

For strict and ‡exible domestic in‡ation-targeting, the weights in the loss function are c = 0; d = 1; = 0; = 0:01;and c= 0; d= 1; = 0:5; = 0:01;respectively:For strict and ‡exible CPI in‡ation-targeting, the weights are c= 1; d= 0; = 0; = 0:01;and c= 1; d= 0; = 0:5; = 0:01;respectively:The choice of the interest smoothing parameter balances two contrasting goals: To avoid a completely unrealistic monetary policy, which may occur when values of are too small and, on the other hand, to avoid an ine¢ cient monetary policy as to the stabilization of CPI in‡ation, which instead occurs when is not su¢ ciently small.

First of all, Table 1 shows that the optimal monetary policy is very simple: only the coe¢ cients for expected domestic in‡ation td+1jt, the lagged interest rateit 1and,

in the ‡exible case, the output-gap in the domestic sectorydt and foreign variables t andyt are sizeable, with the coe¢ cient forit 1 di¤erent from zero because of interest

rate smoothing.

Second, domestic in‡ation-targeting policies, in particular strict in‡ation-targeting, do not depend signi…cantly on the pass-through. Indeed, changes in the type and degree of pass-through have a negligible impact on the coe¢ cients.

Table 2. CPI-in‡ation-targeting, reaction-function coe¢ cients

Strict CPI td td+1jt ti 1 t ytd yti yt it ytd;n yti;n it 1 qt 1 qit 1

Per.; i=0; i=0:05 0.46 -3.27 0.07 -0.01 0.00 0.55 0.54 0.97 -0.01 0.22 0.00 0.02 0.00 Inc.; i=0:5; i=0:05 2.20 -4.24 0.11 0.47 -0.01 1.01 0.76 0.77 0.05 0.26 0.07 -0.43 0.00 Del..; i=0; i=0:5 2.65 0.25 0.40 0.44 -0.02 0.15 0.35 0.15 0.15 0.00 0.43 -0.26 0.00 Del., Inc.; i=0:5; i=0:5 2.10 1.09 0.28 0.30 0.00 0.13 0.22 0.05 0.11 -0.04 0.52 -0.32 0.00

Flexible CPI dt td+1jt ti 1 t ydt yti yt it ytd;n yti;n it 1 qt 1 qit 1

Per.; i=0; i=0:05 1.09 -1.62 0.06 0.33 0.08 0.53 0.67 0.89 0.22 0.15 0.03 -0.18 0.00

Inc.; i=0:5; i=0:05 2.02 -2.49 0.09 0.47 0.30 0.79 0.66 0.62 0.11 0.15 0.12 -0.42 0.00

Del..; i=0; i=0:5 1.36 -0.93 0.27 0.11 0.62 0.08 0.17 0.10 -0.10 0.02 0.33 0.02 0.00

Del., Inc.; i=0:5; i=0:5 0.88 -0.28 0.16 0.08 0.69 0.05 0.10 0.03 -0.10 -0.00 0.36 -0.03 0.00

Third, in contrast with the domestic in‡ation-targeting case, Table 2 shows that with CPI in‡ation-targeting the reaction function is sophisticated. This could be a disadvantage in that it could lead, in practice, to implementation problems. Further-more, with CPI in‡ation-targeting, the pass-through a¤ects the optimal monetary policy. Here, changes in sign and size of the coe¢ cients stand out and show that with respect to the benchmark case of perfect pass-through, incomplete and delayed pass-through tend to have opposite e¤ects on the monetary policy. In particular, incomplete pass-through leads to a more aggressive monetary policy while delayed pass-through leads to a less aggressive one. This result will also show up below in the Impulse Response Functions (IRFs). The intuition is that delayed pass-through re-duces the e¢ ciency of the DERC much more than incomplete pass-through23. Thus, the stabilization of CPI in‡ation requires a monetary policy which is more aggressive with delayed pass-through than with incomplete pass-through. Yet, a too aggressive monetary policy is not feasible because it generates more volatility in the interest rate and in the output-gap which increase the loss of the central bank24. As a result, with delayed pass-through, the optimal transmission mechanism uses the DERC channel less and monetary policy tends to give up the stabilization of ct.

2 3This is apparent in (22) and (23) which show that delayed and incomplete pass-through a¤ect

i

t in a non linear and linear way respectively.

2 4Further results available on request show that reducing the concern of the central bank on the

interest rate smoothing and the stabilization of the output gap (in the ‡exible case) determines a monetary policy that with delayed through is more aggressive than with incomplete pass-through.

3.2 Impulse responses

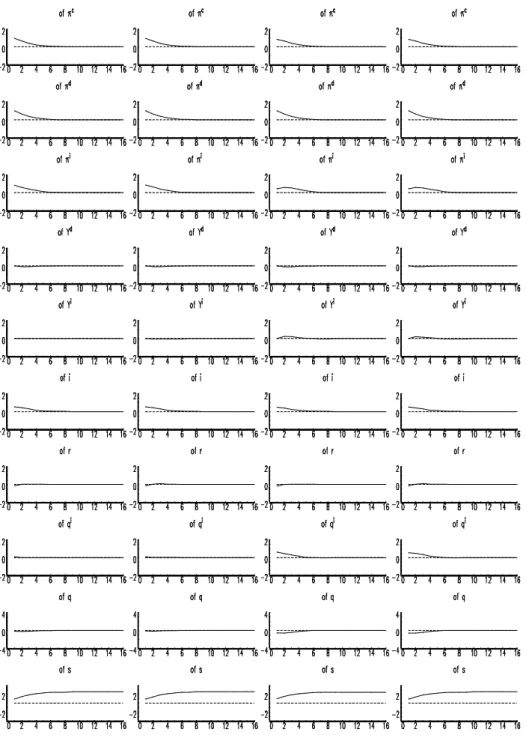

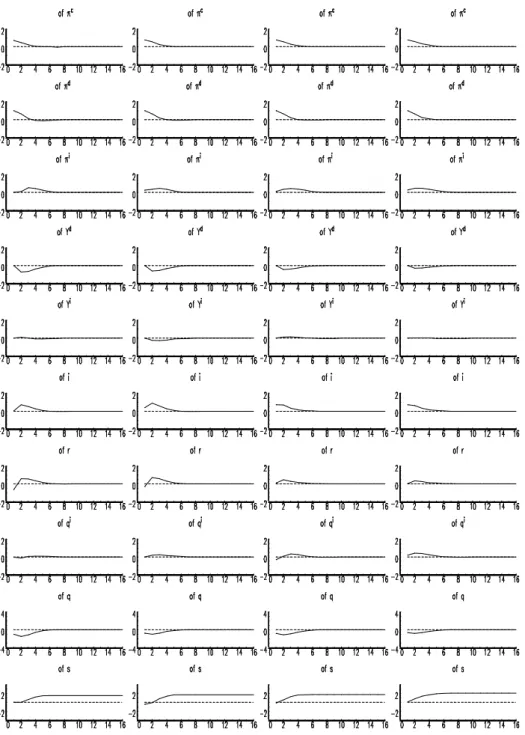

In Figures (3-10) the impulse responses for domestic and CPI in‡ation-targeting under di¤erent assumptions on the pass-through are reported. They are generated assuming that the economy is in steady state and then is hit by a certain shock whose value is set equal to 1.

In each …gure, the …rst, second, third and fourth column refer, respectively, to the cases of perfect, incomplete, delayed and both incomplete and delayed pass-through. The shocks considered are a cost-push shock (Figures 3-6) and a foreign in‡ation shock (Figures 7-10). For sake of simplicity but without loss of generality, the description of the impulse response functions skips the intermediate step from the change of the instrument to the nominal exchange rate. In this way I focus directly on the impact of the monetary policy on the variable qti;which is central in the use of the DERC. Yet, for sake of completeness I report the behavior of the nominal exchange rate which can always be explained by purchasing power parity (satis…ed in the long run) and the uncovered interest parity provided by equation (5).

3.2.1 Strict domestic in‡ation-targeting, IRF to a cost-push shock

In Figure 3, optimal monetary policy works mainly via the aggregate demand channel and the two exchange rate channels other than the DERC.

Monetary policy consists of an initial increase of the nominal interest rate which is gradually taken back to zero (sixth row). Then, the real interest rate rises (seventh row) provoking a fall of the output-gap in the domestic sector (fourth row); this is the aggregate demand channel.

In order to contribute to the stabilization of d, the terms of trade, q, decreases. As a result, some demand switches from domestic to import goods (…rst exchange rate channel that adds to the aggregate demand channel) while the real price of the input in the domestic sector falls (second exchange rate channel that works via the production costs in the domestic sector).

Since in the import sector the switching demand e¤ect tends to outstrip the e¤ect of the increase in the real interest rate, yi slightly rises initially (…fth row). Now, a decrease in q occurs if and only if dis larger than i. Thus, to curb the increase of in‡ation in the import sector caused by yi,qi has to decrease.

With incomplete pass-through (second column), the cost-push shock propagates toqi via equation (23) and the monetary policy lets thatqi increase via the interest parity in terms of qi: Consequently, to avoid that i increase too much, yi has to fall (…fth row). This happens because now the aggregate demand e¤ect outstrips the switching demand e¤ect, and this is consistent with a path ofq which is less negative than before.

With delayed pass-through (third column), a change inqi and yi have a smaller impact on i. Now only half of the …rms in the import sector can update the price optimally so that the elasticity of in‡ation to the real price of the input and to the output-gap in the import sector is much smaller25. Thus, monetary policy provokes a smaller increase in the import sector in‡ation, which in turn determines a larger decrease of the terms of trade. As a result, there are a stronger switching demand e¤ect and fall in the price of the domestic sector input, which explain why monetary

2 5

Note that in the case of immediate pass-through this elasticity tends to in…nity so that an in…nitesimal change ofqi

policy can be slightly more moderate. It is worth noting here that delayed pass-through, by reducing the e¢ ciency of the DERC, tends to improve the e¢ ciency of the overall transmission mechanism, in particular of the other two exchange rate channels. Indeed, allowing this channel to absorb some of the monetary policy shock results in a smaller increase in the import sector in‡ation, which leads to a larger decrease of the terms of trade.

3.2.2 Flexible domestic in‡ation-targeting, IRF to cost-push shock

In the ‡exible domestic in‡ation-targeting cases (Figure 4), monetary policy is similar to, but more moderate than, the strict cases. Here the output-gap in the domestic sector is almost completely stabilized at the cost of a slightly longer period to stabilize domestic in‡ation.

3.2.3 Strict CPI in‡ation-targeting, IRF to cost-push shock

In Figure 5, with perfect pass-through (…rst column), optimal monetary policy man-ages to stabilize CPI in‡ation (…rst row) after a cost push shock. In the …rst two periods this shock can be absorbed only via the DERC and the direct expectation channel because domestic in‡ation is predetermined. As a result, to let in‡ation in the import sector o¤set the shock, monetary policy cuts the interest rate in t, in-creases it sharply in t+ 1 and takes it to zero in the subsequent periods. Such a policy allows qi to be su¢ ciently negative in the initial periods so that it outweights

the positive impact ofyi on the path of i:As to the rest of the economy, the sizable decrease of the terms of trade (ninth row) determines a strong switching demand e¤ect portrayed respectively by the fall and rise of the output-gap in the domestic and import sector (fourth and …fth row).

When the pass-through is incomplete (second column), the ability to fully stabilize CPI in‡ation tends to decrease. Now the price of the input in the import sector depends also on local factors and, consequently, the DERC is less e¢ cient. Thus, a more aggressive monetary policy is required which, however, is bounded by the interest smoothing constraint.

When the pass-through is delayed (third column) only half of the …rms in the import sector is allowed to update optimally the current price of the import. This results in a more relevant reduction of the DERC e¢ ciency because now optimal monetary policy can reduce the current cost of production only for half of the …rms. Thus, an even more aggressive and volatile monetary policy is required to stabilize CPI, which is not feasible due to the interest smoothing constraint. As a result, CPI in‡ation stabilization is reduced even more.

Finally, when the pass-through is incomplete and delayed (fourth row), these two sources of ine¢ ciency of the DERC add up resulting in a largest variability of CPI in‡ation.

3.2.4 Flexible CPI in‡ation-targeting, IRF to cost-push shock

With ‡exible CPI in‡ation-targeting, Figure 6, an intense use of the DERC to stabilize CPI in‡ation is no longer feasible due to the deep and long fall that it would generate in the output-gap. Yet, comparing this case with the ‡exible domestic in‡ation-targeting case reported in Figure 4, shows that in the initial periods, in the former case, in‡ation in the import sector is kept low in order to stabilize CPI in‡ation.

Thus, the DERC is still actively used in ‡exible CPI in‡ation-targeting, and the third row in Figure 6 reveals that its role in the transmission mechanism tends to decrease moving from perfect to the imperfect pass-through cases.

3.2.5 Strict domestic in‡ation-targeting, foreign in‡ation shock

It is noteworthy that in this model shocks in foreign in‡ation or income tend to have a similar qualitative impact on the domestic economy. This is due to the fact that to a large extent they share the same transmission mechanism because the foreign economy is assumed to set the monetary policy according to the Taylor rule. Indeed, a change in either foreign in‡ation or income has the same qualitative impact on the foreign interest rate, which in turn a¤ects the domestic interest rate through the uncovered parity condition. In addition, foreign in‡ation and income have a similar impact on the demand of home goods via the aggregate demand channel.

For example, let us consider a foreign in‡ation shock. Now domestic in‡ation is una¤ected in the …rst two periods and from the third period on it depends on the sequence of expectations of the output-gap and of the terms of trade taken int26. The shock increases the price of the input in the import sector. When the pass-through is perfect (Figure 7, …rst column), all the …rms in the import sector respond optimally to the shock in period t: Since demand is predetermined, the …rms in the import sector can o¤set the shock completely by raising their price in period t (third row). This determines an increase of the terms of trade (eight row), which on the one hand switches the demand from the import to the domestic sector and, on the other hand, tends to increase the production costs in the domestic sector. Therefore, to avoid an upward pressure on domestic in‡ation, the optimal monetary policy increases the nominal interest rate causing a slight fall of the output-gap in the domestic sector (fourth row).

When the pass-through is incomplete (second column), both foreign goods and local inputs are used in the import sector. Thus the impact of the foreign in‡ation shock on the production cost in the import sector decreases. As a result the opti-mal monetary policy and the response of the economy exhibit only a quantitative di¤erence with the perfect pass-through case.

With delayed pass-through (third column), only half of the …rms in the import sector can react optimally to the shock. This explains why in‡ation in the import sector and the terms of trade rise less (third and ninth row) and the real cost of production in the import sector rises more (eight row).

It is interesting to note that the type and degree of pass-through do not a¤ect the ability of the central bank in stabilizing domestic in‡ation. However, imperfect pass-through tends to shield the economy from the shock in that it reduces the e¢ ciency of the DERC in propagating the shock. This is more apparent in the case of delayed and incomplete pass-through, (fourth column), which is characterized by less variability of i; c andq.

3.2.6 Flexible domestic in‡ation-targeting, foreign in‡ation shock

In Figure 8, with ‡exible domestic in‡ation-targeting, the objective of output-gap stabilization slightly constrains the stabilization of d. Furthermore, the monetary

2 6

This can be shown by taking the expectation in t of the domestic sector AS and solving it forward.

policy and the response of the economy di¤er only quantitatively and to a minor extent with the ones with strict domestic in‡ation-targeting.

3.2.7 Strict CPI in‡ation-targeting, foreign in‡ation shock

In Figure 9, for the various cases of pass-through, the monetary policy and the response of the economy are similar: the shock exerts a pressure on in‡ation in the import sector and consequently on CPI in‡ation. The response of the monetary policy consists of a hike of the instrument it (sixth row) which is then gradually taken back

to zero. This policy lets the DERC initially absorb the shock. Then, the aggregate demand channel is available (because the output-gap is no longer predetermined) and it carries out the stabilization of i in the subsequent periods by a fall in the output-gap in the import sector (…fth row). This restrictive monetary policy also determines a fall in the output-gap in the domestic sector (forth row) and it is via the positive path of q (ninth row) that de‡ation in the domestic sector does not occur.

A common feature with the case of strict domestic in‡ation-targeting is that the type and degree of pass-through does not a¤ect the ability of the central bank in stabilizing in‡ation. A di¤erence is that moving from perfect to imperfect pass-through does not reduce the variability of c; i and q.

3.2.8 Flexible CPI in‡ation-targeting, foreign in‡ation shock

As expected, now less variability in the output-gap is achieved at the cost of more variability in CPI in‡ation. The various cases reported in Figure 10 di¤er with the case of strict CPI in‡ation-targeting (Figure 9) for a minor use of both the DERC and the aggregate demand channel. These changes are re‡ected for the DERC in a larger in‡ation in the import sector (third row) and, for the demand channel, in a minor decline of the output-gap (fourth row). This result is obtained with a slightly di¤erent interest rate plan that results in a less tight monetary policy.

4

Imperfect pass-through and volatility in economic

ac-tivity

This section focuses on the relation between the pass-through and the volatility in economic activity and analyzes how the central bank could use this relation to improve its stabilization task.

4.1 Taylor curves

Figure 1 and 2 below illustrate, respectively, the Taylor curves for various degrees of incompleteness and delay of the pass-through when the central bank is following CPI in‡ation-targeting.

std

Ý

^

cÞ

std

Ý

y

dÞ

SIT 0 0.2 0.4 0.6 0.8 1 1.2 1.4 1.6 1.8 1.5 2 2.5 3 3.5 4 FIT Wi= 0 Wi=0. 6 Wi=0. 4 Wi= 0.2Figure 1. CPI in‡ation-targeting with incomplete and immediate PT,

i 2 f0; 0:2; 0:4; 0:6g; i= 0:05: Ji=0.4 stdÝydÞ

std

Ý

^

cÞ

FIT SIT Ji=0.05 0 0.2 0.4 0.6 0.8 1 1.2 1.4 1.6 1.8 2 1.5 2 2.5 3 3.5 4 Ji=0.6Figure 2. CPI in‡ation-targeting with delayed and complete PT,

i

2 f0:05; 0:4; 0:6g; i = 0:

These Taylor curves show that the trade-o¤ between the variability of the output-gap and CPI in‡ation worsens when the pass-through is more incomplete and/or delayed. It is noteworthy that the impact of the pass-through tends to be stronger, the more the central bank cares about CPI-in‡ation stabilization (strict in‡ation-targeting, SIT) versus output-gap stabilization (‡exible in‡ation-in‡ation-targeting, FIT). This is due to the lower e¢ ciency of the DERC, which is important to stabilize CPI in‡ation in the short run.

The relation between the pass-through and the Taylor curves is even more in-teresting if one considers the relation between the in‡ation environment and the pass-through. With respect to the latter, there is a growing view in the literature for that moving to a lower in‡ation environment decreases the pass-through. This idea is consistent with the observation that a lower pass-through coupled with a more credible commitment to stabilize in‡ation has occurred in the last ten years. The-oretically, Taylor (2000) provided the …rst motivation for this relation showing how moving to a lower in‡ation environment reduces the pass-through by decreasing the expected persistence of cost changes. This relation is also supported empirically, for example, in Bailliu and Fujii (2004)27. Thus, if we assume following Taylor (2000)

2 7

For other explanations and empirical evidence concerning the relation between the in‡ation environment and the pass-through see also Coudhry and Hakura (2001), Devereux and Yetman (2002) and Deverux, Engel, and Storgaard (2003).

that a stable and lower in‡ation reduces the pass-through, to achieve a lower vari-ability of CPI in‡ation could turn out to be more costly than expected in terms of output-gap variability. A case in point might be a central bank that decides to switch to in‡ation-targeting. Indeed, consider Figure 2 and suppose that due to a high initial in‡ation the pass-through tends to be immediate, for instance consider the Taylor curve with i = 0:05. Then suppose that the in‡ation variability is around 1 std and

that, on the basis of this Taylor curve, the new in‡ation target monetary policy aims to achieve a variability of 0.4 std accepting a resulting output-gap variability of 3.2 std. Yet, the more CPI in‡ation variability falls, the worse is the trade-o¤ so that it turns out to be impossible to attain the pair (0.4, 3.2). In fact, the pass-through is more delayed (say i = 0:6) and the 0.4 CPI std target requires 4.1 std in the output-gap.

In summary, this analysis leads to two results. The …rst is that it is important to know the type and degree of the pass-through to assess the attainable output-gap-CPI in‡ation variabilities trade-o¤s. The second is that, combining this …nding with the literature on the relation between the pass-through and the in‡ation environment, a chosen variability of CPI in‡ation could be achieved at a output-gap variability cost much higher than expected.

These results suggest an extension for further research in introducing endoge-nously the impact of the monetary policy on the pass-through. This could be done for instance via a Phillips curve that allows the degree of price stickiness to be de-termined endogenously as in Bakhshi et al. (2004).

4.2 Unconditional standard deviations, imperfect exchange rate pass-through and choice of the in‡ation target

The following tables report the unconditional standard deviations for the main macrovari-ables in the model.

Table 3: Unconditional standard deviations

Targeting case

ct td ydt qt it rt

1. Strict domestic in‡ation-targeting

1.a Perfect PT 1.27 1.22 1.52 4.11 1.41 0.88

1.b.Incomplete PT 1.17 1.22 1.50 2.62 1.47 0.92

1.c Delayed PT 1.01 1.22 1.52 2.68 1.35 0.82

1.d Incom. and del. PT 1.04 1.22 1.49 2.08 1.43 0.89 2. Flexible domestic in‡ation-targeting

2.a Perfect PT 1.56 1.30 1.26 4.09 1.32 1.11

2.b Incomplete PT 1.38 1.29 1.26 2.61 1.35 1.15

2.c Delayed PT 1.21 1.29 1.27 2.42 1.30 1.13

2.d Incom. and del. PT 1.20 1.29 1.26 1.83 1.33 1.14 3. Strict CPI in‡ation-targeting

3.a Perfect PT 0.03 1.51 4.17 7.80 3.59 4.60

3.b Incomplete PT 0.17 1.51 4.70 7.22 5.08 5.98

3.c Delayed PT 0.46 1.36 3.04 5.61 4.37 4.35

3.d Incom. and del. PT 0.69 1.30 3.32 3.91 4.31 4.20 4. Flexible CPI in‡ation-targeting

4.a Perfect PT 0.94 1.23 1.72 3.13 2.02 2.10

4.b Incomplete PT 1.05 1.22 1.59 2.36 2.06 1.99

4.c Delayed PT 1.03 1.24 1.45 2.78 1.49 1.18

4.d Incom. and del. PT 1.09 1.24 1.34 2.04 1.48 1.19

First, Table 3 shows that the impact of the pass-through on the volatility of the economy is smaller with domestic than with CPI in‡ation-targeting. Indeed, with domestic in‡ation-targeting only the variability of c and q decreases signi…cantly when the pass-through is incomplete and/or delayed. In particular, the variability of yd is not a¤ected. In contrast, with CPI in‡ation-targeting, the pass-through also a¤ects the variability of the other variables. Furthermore, with CPI in‡ation-targeting the variability in economic activity tends to rise. Yet, the concern for interest rate smoothing and the output-gap stabilization prevents it from increasing too much28.

Second, imperfect pass-through tends to have opposite e¤ects on the volatility of

c with the two in‡ation targets. Speci…cally, it decreases the volatility with domestic

in‡ation-targeting while increases it with CPI in‡ation-targeting. Furthermore, with any in‡ation targets, imperfect pass-through reduces the variability of q. These results depend on two factors. The …rst is that imperfect pass-through reduces the e¢ ciency of the DERC. Since CPI in‡ation stabilization relies signi…cantly on this channel, less e¢ ciency of the DERC requires a more aggressive monetary policy that, in turn, leads to an excessive variability of the other macro variables, in particular

2 8

This explains why, with strict CPI, moving from the benchmark case to the incomplete pass-through case, the variability of c; yandiincrease. Yet, moving from the benchmark case to delayed pass-through, the variability ofirises less, of crises more and the one ofyfalls.