2

Chapter

Table of Contents

Strategic Planning 2.2

Step 1: What Is the Problem? 2.3

Step 2: Who Is Most Affected and What Do You Need to Know about Them? 2.8

Step 3: What Can be Done? 2.2

Step 4: How Can the Goals and Objectives be Reached? 2.4

Step 5: Where Can You Get Help? 2.20

Step 6: How Will You Know What You Achieve? 2.2

Step 7: What Are the Next Steps? 2.23

Bibliography 2.24

Appendix

2.: Campaign Planning Worksheet 2.25

2.2: Sources of Information on Demographics and Tobacco Control and Use 2.30 2.3: Health Canada’s “Bob and Martin” Smoking Cessation Campaign Overview 2.32

2

Chapter

Global Dialogue Campaign Tool Kit

Planning is the foundation of your tobacco control campaign. Sound planning alone cannot guarantee success, but it is a very important first step. Effective planning helps you set clear objectives that will enable you to select activities and set priorities. Planning also helps you assess progress and make choices that will enhance your campaign’s chances for future success.

Because this chapter summarizes a strategic planning process, several aspects in the process overlap with program planning steps that are discussed later in the tool kit. It is important that you conduct both strategic planning for the campaign and the specific campaign programmatic planning. These are not duplicative, even though some of the processes may be similar. In strategic planning, you are researching, analyzing and making key decisions about the overall focus and direction of your campaign. In campaign program planning, you are using the strategic planning to guide specific decisions about how to implement your campaign and what components to include. Throughout this resource, we will refer you to other chapters for more details to limit the amount of overlap in the tool kit.

This section describes the steps for strategic planning of your campaign. Become familiar with each of these steps before you start. Much of the planning you do will involve multiple steps at once or require making changes to steps on which you have already worked. With so many demands on your time, you may be tempted to skip some steps, but thorough planning will be worth the time invested. A written plan will help you get support from your organization, partners, stakeholders and funding sources, and will help you respond quickly and effectively to critics.

The sample Campaign Planning Worksheet (Appendix 2.1) can help you begin. You also may want to review CDCynergy for Tobacco Prevention and Control, U.S. CDC’s CD-ROM-based planning tool that includes several tobacco-related case studies from the United States. Information about ordering CDCynergy is available at

http://www.cdc.gov/healthmarketing/cdcynergy.2

Strategic Planning

2.2

“

Developing a tobacco control marketing campaign without first undertaking strategic planning is rather like traveling in an unfamiliar country without a map. You may know what your general destination is, but you do not know how you will get there. Strategic planning provides the necessary direction for your campaign team and your stakeholders.”

St

ra

te

gi

c P

la

nn

in

g

2

Strategic Planning:

Canada

In Canada, Newfoundland and Labrador

established a Tobacco Reduction Strategy through their Department of Health and Social Services with the goal of encouraging and supporting Newfoundlanders and Labradorians to quit using tobacco and stay tobacco free. Local partners organize around different tobacco control issues relevant to their group’s mission to determine how they will work together to accomplish this goal. Under cessation, a key objective of this strategy is to increase the percentage of former smokers in the province from 32 percent to 36 percent by 2008. The provincial Tobacco Reduction Strategy Cessation Working Group identified four key action areas to meet this objective, including increasing the number of qualified health professionals who deliver or refer individuals to appropriate cessation services, and the need to develop and implement a public education strategy to promote smoking cessation among Newfoundland and Labrador priority populations: pregnant women and their partners, new parents, and Aboriginal children, youth and adults.

With these objectives in mind, the Newfoundland and Labrador Lung Association Smokers’ Helpline, one of the members of the Cessation Working Group, used Health Canada funding to develop a mass media campaign called, “It’s Your Call.” The campaign included advertisements geared specifically to pregnant and postpartum women and their partners as well as the Aboriginal community. The objectives of the campaign supported the overall objectives of the provincial tobacco reduction strategy.

“It’s Your Call” Campaign Objectives: Increase Smokers’ Helpline caller volume by 50 percent

Increase the number of smokers who are referred to community-based cessation services by 25 percent

Increase the number of health care providers using the Smokers’ Helpline and CARE Program by 0 percent

Increase the number of new users to the Smokers’ Help Online Web site by 0 percent •

•

•

•

Step 1: What Is the Problem?

Review the tobacco control program goal(s) that your campaign will support. For example, if the overall tobacco control program will focus on helping adult smokers to quit, then your campaign should not focus on prevention of tobacco use among youth.

1a) Describe the Problem.

Once you have reviewed the tobacco control program’s overall goal(s), you can identify the specific problem or issue to address. Make sure that everyone involved in the campaign agrees on what the problem is, and that you understand and can describe it. The amount of information needed to develop a description of the problem depends on factors such as:

How much experience your organization has with the issue. How much information is available on the issue in your area or in a similar locale.

How much research is needed to justify your plan to your organization and to potential critics.

Be specific in describing the problem. Include: Who is affected and how?

How severe is the problem, and what data were used to measure the severity?

Who can positively influence the situation or the affected group? • • • • • •

Global Dialogue Campaign Tool Kit

2.4

Research has shown that campaigns with the following characteristics are more likely to succeed: Clear and specific program objectives.

Multiple target audiences. Multiple tactics.

Multiple types of change.

Specific messages that directly support intended changes.

Messages and activities tailored for different target audiences and different times in the program. Formative research to glean key insights about target audiences, strategies, messages and activities. Message consistency.

Long-term commitment.

A focus on changing social norms.3,4

1b) Describe Who Is Affected.

If possible, describe subgroups that may be affected by the problem more than other groups. These subgroups should be large enough and different enough from one another and the general population to justify distinction. Subgroup descriptions can include:

Demographic information (age, gender, race and ethnicity, education, and family income) Geographic information (location of residence, school and work)

Psychographic information (attitudes, opinions, intentions, beliefs and values)

Become familiar with sources of available data that can help describe the population, the severity of the problem and ways to measure change. Individuals with epidemiologic training or experience can help you find relevant data sources. For more information, see Chapter 3: Target Audience Research and Chapter 5: Campaign Evaluation.

1c) Refine the Problem Statement.

As additional information becomes available, polish your problem statement by adding more detailed descriptions of the subgroups affected. For example, if the original problem statement identified a high rate of adult male smokers in a certain city, further investigation may reveal that the smokers are new immigrants who are largely single and unemployed. A review of the scientific literature and of successful tobacco control programs elsewhere may also reveal that their smoking behavior was likely influenced by the media and peers. This information will help you to develop more tailored campaign approaches for them.

• • • • • • • • • • • • •

St

ra

te

gi

c P

la

nn

in

g

2

Environmental Analysis:

Brazil

In Brazil, the last national survey on risk behaviors showed that despite a considerable drop in smoking prevalence among adults across the country, this was not true for a southern region of the country, where 95 percent of the tobacco planted in Brazil is grown. This region had a higher smoking prevalence. The Brazil Department of Health determined that its messages were not having the same effect on this portion of the country as they were having on the rest of the country; thus the department implemented several studies to understand the dynamics of the tobacco control environment. Using these data, the Brazil Department of Health planned to develop specific tobacco control strategies and campaigns for the

1d) Assess Factors that May Affect the Campaign.

The environment, or situation, in which the campaign exists affects the campaign and its outcomes. For example, suppose you are planning a campaign to encourage people to quit smoking and one of your key messages is that quit smoking medications can be effective. If, at the same time, your government is preparing legislation that will limit the distribution of quit smoking aids to pharmacies, your campaign may not have lasting impact.

One tool that can be used to understand your campaign context is called a SWOT analysis: strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats. This tool uses a series of questions to identify, for your plan, the strengths and weaknesses of the internal environment, and the opportunities and threats of the external environment. For example, does your organization have the necessary authority or mandate? If you answer yes, that may be a strength of your plan. If your answer is no, that may be a weakness of your plan. Other questions to consider include:

Strengths / Weaknesses

Do you have or can you acquire the necessary expertise and resources? Will you be duplicating the efforts of others?

How much time do you have to address this issue? What can you accomplish in that time?

What are the available resources, including funds, time, and personnel and their skills? What is the level of your organization’s commitment to addressing the issue? • • • • • • Opportunities / Threats

What are other concerned or involved groups doing? Are there gaps, opportunities for partnering, or potential overlap in areas being addressed?

Is there sound guidance available to address the problem? What is the political support for, resistance to, or potential criticism of efforts to address the problem?

What policies or lack of policies will help or hinder your efforts?

What are the barriers to behavioral or environmental change or both, including activities of adversaries?

•

• • • •

Global Dialogue Campaign Tool Kit

Also, ask what other countries, regions or non-govermental organizations (NGOs) are doing (or have done) to address the problem:

What have they learned?

Do they have information or advice about targeting, budgeting and evaluating?

From their perspective, what gaps exist in media coverage and advertising, community activities, materials and target audiences?

Are there opportunities for collaborative ventures, especially if key goals and target audiences are the same? Experienced colleagues and contacts at health departments or NGOs can offer suggestions or advice as you conduct this assessment. Keep all the information gained through this assessment in mind as you develop the campaign. • • • •

Developing a Plan

Quickly: Norway

When Norway’s Minister of Health declared that he wanted to reduce youth smoking by 50 percent within five years, the Norwegian Directorate for Health and Social Affairs had three months to implement a campaign. The Directorate’s staff had to decide quickly what was possible within their timeframe and the limited budget they had available. They knew that a scientific evaluation had shown that one of the most effective strategies to address youth smoking was mass media campaigns, but they had very little time to develop advertising. They searched the literature for other campaigns that had shown effectiveness and decided to use the Australian campaign “Every cigarette is doing you damage” with appropriate translations. This campaign had already been tested on a Norwegian audience and was easy to adapt in the short timeframe. Knowing and understanding the external environment helped them to move forward with the campaign in a very cost and time-efficient manner.

Kari Huseby, Director, Tobacco Control Department, and Kristin Mosaker Granborg, Adviser, Communication and Documentation Department, Directorate for Health and Social Affairs, Norway.

St

ra

te

gi

c P

la

nn

in

g

2

Review the SWOT analysis in light of your desired campaign plans. Is a campaign possible at this time? Do you have enough strengths and opportunities to address the weaknesses and threats? You may need to revisit your plan, solicit additional resources or supports, or address a particular threat in your environment before proceeding with your plan. Keep the results of your SWOT analysis so you can review them frequently as you develop your tobacco control campaign.

1e) Review Relevant Theories and Models.

Review theories and models on the target audiences and the steps that might influence them. Theories can help to explain why problems exist, identify what you need to know about the target audience, and what you need to do to influence change. Theories and models also can guide you in choosing realistic objectives, determining effective strategies and messages, and designing an appropriate evaluation. Because issues, populations, cultures, contexts and intended outcomes vary, many programs are based on several theories. See Table in the U.S. National Cancer Institute’s Theory at a Glance: A Guide for Health Promotion Practice for a summary of some key theories that can help guide your efforts.5 Theory at a Glance is available online at http://www.cancer. gov/theory.pdf. Another helpful reference is the Communication Initiative’s Change Theories at http://www.comminit.com/ changetheories.html.6

Strategic Planning

Resources

There are many resources available to support strategic planning efforts for social marketing campaigns. Here are some that are relevant for tobacco control campaigns:

Centers for Disease Prevention and Control, United States

Designing and Implementing an Effective Tobacco Counter-Marketing Campaign

Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/media_ communications/countermarketing/campaign/00_ pdf/Tobacco_CM_Manual.pdf

The Communication Initiative Available at: http://www.comminit.com/ Global Dialogue for Effective Stop Smoking Campaigns

Overview of Evidence Based Recommendations for Stop Smoking Campaigns (Based on Lessons Learned from International Literature Review and Unpublished Campaign Results)

Available at: http://www.stopsmokingcampaigns. org/uploads/OverviewofEvidence.pdf

Health Canada’s Social Marketing E-Learning Tool

Available at: http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/ahc-asc/activit/ marketsoc/tools-outils/index_e.html

National Cancer Institute, United States

Making Health Communication Programs Work

Available at: http://www.cancer.gov/pinkbook World Health Organization

Building Blocks for Tobacco Control: A Handbook

Available at: http://www.who.int/tobacco/resources/ publications/tobaccocontrol_handbook/en/

Step 2: Who Is Most Affected and What Do You Need to Know

about Them?

In Step , you identified who was affected by the problem, but the broad population affected may be made up of diverse subpopulations. One or several target audience(s) should be selected for tailored efforts on the basis of each group’s shared characteristics. For example, if your goal is to reduce smoking by motivating smokers to quit, but some young adults do not consider themselves smokers because they only smoke when they socialize with friends, you may need to target those “social” smokers with unique messages.

Analysis of Sub-Populations:

United Kingdom

In the United Kingdom, the 200 census showed that 9 percent of the population is white (Caucasian), and the next largest group is South Asians, primarily of Indian, Pakistani and Bangladeshi origin.

The overall smoking prevalence of South Asians living in the United Kingdom is lower than that of whites and, thus, you might conclude that this group does not need to be targeted for tobacco control efforts. However, the organization QUIT UK analyzed the data more thoroughly on the grounds of race, religion, age and ethnicity, and determined that some sections of these communities actually smoke at the same level, or higher, than whites do. This was confirmed in the Health Survey of England 2004, published in 2006.

Older men smoke more than younger men (nearly 55 percent prevalence rate in Bangladeshi men older than 50) and the smoking rate of South Asian men is hidden in the

overall prevalence number by the very low rate of smoking among South Asian women ( percent to 6 percent, as compared with about 2 percent among white women). Thus, QUIT UK saw the need to target older South Asian men in its smoking cessation efforts. Since a majority of these men are Muslim and religion has a strong role in their everyday behaviors and social lives, QUIT UK decided to focus smoking cessation efforts around religious practices of the men. QUIT UK worked with Muslim religious leaders to communicate stop smoking messages through mosques and community organizations. These messages were tied to Ramadan, the month of fasting and self reflection, by working with restaurant owners to offer smoke-free dinners for patrons to break their fast. QUIT UK also reached out to Muslim media owners and collaborated on health programming about tobacco use. Through these combined efforts, QUIT UK was able to significantly build awareness of tobacco-related issues and increase response to quitting services (Quitline®,† Web site and counseling).

Kawaldip Sehmi, Director Health and Equality, QUIT UK.

2.8 Global Dialogue Campaign Tool Kit

† England is served by two different telephone-based stop smoking services. QUIT UK is a non-governmental organization that provides telephone-based smoking cessation

counseling services across the United Kingdom. This service is called Quitline®. In England, the National Health Service has a different telephone service called the Smoking Helpline that provides counseling, information and referral services to residents of England. In this tool kit, UK Quitline is used to refer to the QUIT UK telephone smoking cessation counseling service. England helpline or the NHS Smoking Helpline are used to refer to the National Health Service’s counseling, telephone information and referral service. Quitline is used to refer to telephone smoking cessation services in other countries and communities.

St

ra

te

gi

c P

la

nn

in

g

2

In some cases, the target audience(s) may not be the affected population. If you want to reach pregnant women who smoke, you might target their spouses or partners. The primary audience is pregnant women, the secondary audience is their spouses or partners. Influencing the pregnant woman’s partner to support her attempts to quit smoking may increase the likelihood that she is successful.

Understanding the target audience(s) before you plan and develop your program is essential. To be successful in influencing them, you will need to understand the problem and potential changes from the target audience’s point of view. Define the audience you want to reach, the results you want to achieve, and how to measure those results. Also, find out about the target audience (lifestyle, attitudes, environment, culture, knowledge, beliefs and behaviors), so you can plan appropriate activities while staying focused on your program objectives.

If reliable data on a certain group are not available, you may need to conduct qualitative or quantitative research or both to learn enough to make sound planning decisions. See Chapter 3: Target Audience Research for more information on conducting audience research.

2a) Clearly Define the Audience You Want to Reach and the Result to be Achieved.

No program can do everything for everyone. Choosing a target audience provides a focus for the rest of your planning decisions. To select your target audience(s), answer the following questions:

What is the problem?

What is the solution or desired outcome?

Who is most likely to be able to make the desired changes happen? How specifically can you describe the target audience(s)?

How large is this group or groups? Each group should be large enough to make a difference in the problem but should not include so many types of people that you cannot specifically tailor your efforts.

This review may leave you with many options. The following questions will help you narrow your focus: Which audiences represent the highest priorities for reaching the key tobacco control goals? Which audiences can be most easily reached and influenced?

Which audiences are affected disproportionately by the health problems associated with tobacco use? Which audiences are most unique and identifiable, and large enough to justify intervention?

In which audiences would campaign efforts duplicate the efforts of an existing program or campaign? Which audiences, if any, have higher or lower priority because of political considerations?

How are key opinion leaders, like physicians, addressing tobacco use with their clients? • • • • • • • • • • • •

Global Dialogue Campaign Tool Kit

2b) Find Out More about the Target Audiences.

What “drives” the actions and behaviors of audience members, what interests and appeals to them, and where you can reach them are essential pieces of information for campaign design. Also, take the time to understand cultural contexts that influence how target audience members live and make decisions. See Appendix 2.2 Sources of Information

on Demographics and Tobacco Control and Use and Chapter 3: Target Audience Research for more information on understanding specific populations.

Answering the following questions about the target audience(s) will help you plan an effective campaign:

What are the attitudes and beliefs of the target audience related to tobacco use? Do they understand the negative consequences of smoking? Is there a lack of openness to seeking professional help for medical problems? Is there a belief that individual rights should be protected over group rights? Are there misconceptions that need to be corrected? What barriers to change must be addressed?

Are there social, cultural and economic factors to consider? For example, does a high percentage of the target audience report that it is difficult to turn down a waterpipe offered at a party? Do they perceive smoking or snuff as “popular” and “desirable”? Do some individuals view cigarettes or bidis as a positive symbol because of cultural beliefs and practices? Does the price of chewing tobacco influence the amount used? Do some smokers find ways around pricing changes, such as stealing, getting tobacco products from friends and family, buying “loosies” (single cigarettes typically sold at small convenience stores or on the street) or buying cigarettes on the illegal market? Does the acceptability of smoking among men versus women influence public and private behaviors?

•

•

Counteracting Tobacco

Industry Influence: Brazil

During the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) ratification process in Brazil, tobacco control advocates conducted specific research to identify the issues and concerns of the members of the National Congress who were delaying ratification of the FCTC. The research revealed that the tobacco lobby had used tobacco growers in the powerful southern region to spread misinformation about the FCTC and its impact on tobacco-growing regions. As a result, tobacco control advocates developed new messages and materials to counteract these messages. The FCTC was ratified, following a two-year effort, in November 2005. Marcus Frohe, Tobacco Control Program Senior Analyst, National Cancer Institute of Brazil.

Where can audience members be reached? In the community? In school? At home? Through television? Radio? Print? Interactive media? What is a typical day in the life of an audience member? What are the audience’s preferences in terms of learning styles, language and tone of messages? Some people learn through reading and contemplation; others prefer discussion. Some may be motivated by positive appeals, while others may be more influenced by fear and other negative emotions. For example, the promise of a healthy baby might motivate a pregnant woman to quit smoking, while the threat of serious heart disease might move a middle-aged man with borderline hypertension to quit. What are the audience’s preferences in terms of activities, vehicles and involvement in the issue of tobacco? Some smokers may prefer to quit on their own. Others may welcome access to a quitline counselor.

•

•

•

Understanding Tobacco

Use Patterns: Chile & Syria

In Chile, where youth smoking rates are among the highest in South America, 6 percent of 3- to 5-year-olds are exposed to secondhand smoke in their homes, 69 percent have one or more parents who smoke, 2 percent are around others who smoke outside the home, 38 percent say all or most of their friends smoke, 6 percent usually smoke at home, and 60 percent buy cigarettes in stores, suggesting that the environment in which children are raised in Chile influences their smoking behavior.

Syria, and the eastern Mediterranean region, is witnessing a dramatic resurgence of a traditional tobacco use method, the waterpipe. Barely seen some decades ago, the waterpipe is enjoying a huge popularity among youth, accompanied by societal acceptability (especially for girls), and a perception of reduced harm due to the assumed filtering effect of water.8 Studies of university students in Syria and Lebanon show that current waterpipe use is reported by 28.3 percent of students (Lebanon), and 45 percent of students reported having used the waterpipe at some time (Syria).9 Unlike cigarettes, waterpipe use in Syria is seen more in younger and more affluent groups. For example, in a population-based sample of 2,038 adults (8-65 years) in Syria, waterpipe smoking was reported by . percent of the 8- to 29-year-old age group compared with 5. percent in the 46- to 68-year-old age group. In the same survey, waterpipe use in the upper socio-economic group was reported by 2.2 percent compared with 8.9 percent in the middle and 4 percent in the lower socio-economic groups.0

St

ra

te

gi

c P

la

nn

in

g

2

Your campaign plan should include the following information about each of your target audiences.

Demographics: gender, age, educational attainment, occupation, income, family situation, and location of residence, work and school.

Community norms and lifestyle characteristics: language preferences and proficiencies, religion, ethnicity, generational status, family structure, degree of acculturation, and lifestyle factors such as food and activity preferences.

Media preferences: media use, places where they might be receptive, and types of messages, sources or sponsors perceived as credible.

Readiness to change: behaviors, knowledge, attitudes, values and feelings that indicate the audience’s willingness to accept and act on the information provided.

An audience profile that you will use for developing your campaign plan does not need to be comprehensive, but it does need to provide you with enough information to understand the strategic direction of your plan. Below is a sample audience profile for “social” smokers.

Audience Profile for “Social” Smokers

Young adults, 8-30 years old, who do not smoke every day and throughout the day, but instead smoke frequently when they socialize with friends. They may smoke an average of 0-5 cigarettes each day but that average may be based on not

smoking three days each week and smoking a full pack of cigarettes Thursday through Sunday nights when they are out at clubs and bars. They do not see themselves as smokers and do not think they are addicted since they do not smoke every day.

•

•

•

Global Dialogue Campaign Tool Kit

Step 3: What Can be Done?

Defining your campaign objectives will help you determine messages, set priorities and establish the outcomes to be measured. Objectives should reflect the results expected from the campaign within the given timeframe and within the context of a comprehensive tobacco control program. In general, campaigns can:

Raise awareness about the negative consequences of tobacco use and about the campaign. Increase knowledge about the risks of tobacco use and exposure to secondhand smoke. Shape or shift individual attitudes or values, contributing to behavior change.

Change community norms.

Result in simple actions (asking for help or information).

Gain broad public support for tobacco control issues, including legislative issues.

As an example, campaign activities designed to support quitting smoking might be expected to: Communicate the benefits of quitting or the risks of continuing to use tobacco.

Increase support for coverage of quit smoking medications and services under private and public insurance. Prompt use of services, such as quitlines.

Set achievable and measurable objectives so you can show that you have succeeded or are making progress. Doing so can maintain and increase support for your program. If you plan to specify a numerical goal for a particular objective, an epidemiologist, statistician or marketing expert can offer guidance on reasonable rates of change. (For example, commercial marketers often consider a 2 percent to 3 percent increase in sales to be a great success.) Be ready to include your evaluator in the discussion to help develop draft objectives.

Write objective(s) that answer these questions:

What specific effect do you hope to have on the tobacco-related problem? Among which target populations do you hope to make an impact? How much change do you expect?

When do you expect to see change? (Include milestones that will help you identify progress.)

For example, if a country sets its tobacco control program goal as reducing exposure to secondhand smoke in public places, then the campaign goals could be to ) motivate smokers not to smoke around nonsmokers and 2) motivate nonsmokers to speak up when others smoke around them. Based on these goals, the campaign objectives might be:

Increase the percentage of smokers who agree that secondhand smoke causes serious health effects to nonsmokers from 4 percent to 65 percent within nine months, and among nonsmokers from 62 percent to 80 percent within nine months.

Increase the percentage of smokers who agree with the statement “I can protect people I care about from illnesses by not smoking around them,” from 40 percent to 60 percent in twelve months.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • 1. 2. 2.2

St

ra

te

gi

c P

la

nn

in

g

2

Increase the percentage of nonsmokers who agree with the statement, “It’s my right and the right of my loved ones to breathe smoke-free air” from 38 percent to 55 percent within six months.

If the campaign has sufficient funding, it can focus on the two target audiences of smokers and nonsmokers with unique messages. However, if funding is very limited, the goals and objectives need to be adapted as appropriate. Ensure that your objectives are developed thoughtfully. Poor objectives can lead to the failure of your campaign because of misaligned expectations, measuring the wrong outcomes or not having appropriate measurement tools. Failing to meet your campaign objectives may mean that stakeholders will not support your program, leading to loss of credibility and/or funding. Some common mistakes people make when developing objectives are:

Objectives without measure

You need to be able to measure the objectives that you are seeking. If you want to show that your campaign increased the number of people who believe that quitting smoking is possible, you need to have a baseline measure for that belief before the campaign and then be able to measure it again after the campaign. If you want to measure the reduction in children’s exposure to secondhand smoke following your campaign, you need to know what evaluation tool and approach you will use to measure that.

Measuring the wrong indicator

You must measure the specific change or issue that your campaign is addressing. Using the same example as above, if your campaign is focused on increasing the number of people who believe that quitting smoking is possible, and your evaluation only measures the number of people who quit smoking, you will not be accurately measuring the impact of the campaign. Instead, you need to measure both changes in relevant beliefs (such as the belief that quitting is possible) and changes in behaviors (such as quitting) to know whether your campaign is making an impact.

Setting unreasonable objectives

Behavior change, such as quitting smoking, is difficult to achieve. Before you can expect members of a population to make a behavior change, they must go through a number of other changes—in awareness, in knowledge, and in personal beliefs and attitudes. If you set an objective of increas ing the number of people who successfully quit smoking in just six months after the start of your campaign, you are not likely to achieve it and that will set up your campaign for failure.

Chapter 5 offers more information on developing objectives that are Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant and Time-bound (SMART). An example of a SMART objective might be to increase by 20 percentage points the number of smokers who call the health department’s quitline, from 0 percent to 30 percent, and to increase by 5 percentage points the number who stop smoking 3.

Global Dialogue Campaign Tool Kit

2.4

Step 4: How Can the Goals and Objectives be Reached?

Now you can begin to develop a detailed tobacco control marketing campaign plan.

4a) Select the Approaches to Use.

Four key campaign approaches are described here: advertising, public relations, media advocacy and community-based marketing. Most of this tool kit is devoted to helping you to plan and implement these specific campaign tactics, and each one is discussed in detail in a separate chapter. Here is a quick look at these approaches, along with examples of what they can and cannot contribute to your campaign.

Advertising is a communications approach in which messages are repeatedly delivered to a broad audience typically through mass media. Advertising permits control over the message’s tone, content and amount of exposure.

Advertising can communicate a single, simple message to many people; change attitudes; create an image for the campaign; and expose the practices of adversaries or competitors.

Advertising cannot provide complex information, feedback or services.

Public relations is used to build a positive reputation or image for the tobacco control program or the tobacco control issue, typically through “earned” media coverage—news coverage of the program and issue generated through activities and relationships with reporters and other media gatekeepers.

Public relations can establish ongoing relationships with media, stakeholders, opinion leaders and others; reach audiences with information and messages that are typically seen as more credible than advertising; gain public support and create a positive environment for the program; expose the practices of adversaries or competitors; and provide a quick response to issues and events as they arise.

Public relations cannot guarantee a story’s placement, exposure, focus, slant, content or accuracy.

Media advocacy is the strategic use of media and community support and action to create social or policy change. This approach often uses “earned” media, but can also include paid media placements to get key messages across.

Media advocacy can help communities create lasting change by changing norms and behaviors at the community level.

Media advocacy cannot guarantee individual behavior change based on new information.

Community-based marketing involves people at the local level as participants in a tobacco control campaign. Community-based marketing can get people involved in the issue or program at the local level, create interpersonal exposure to the message, channel feedback and build community support.

Community-based marketing cannot be tightly controlled or expose a broad audience to a very specific message. • • • • • • • • • • • •

St

ra

te

gi

c P

la

nn

in

g

2

Combining several approaches is usually better than using just one. Any approach you choose must fit into your broader tobacco control program strategy. The best advertising or public relations work will not make up for a lack of strategy. The following questions can help you decide which approaches to use:

Which approach or combination of approaches best addresses the problem and your campaign objectives? Which options are most appropriate for your target audience(s)?

Which approach(es) can your organization successfully implement with its available skills, budget and experience? Could any of the approaches cause undesirable unintended effects, such as public or political criticism?

4b) Review and Select the Channels to Use.

Channels, or vehicles, are pathways used to deliver program messages, materials and activities to your target audience. Channels can be divided into four broad groups: interpersonal, community and organizational, mass media, and interactive and electronic media.

Interpersonal channels put health messages in a familiar context. Examples of interpersonal channels are physicians, friends and family members, counselors, parents, clergy, tribal leaders, respected elders, sheikhs, educators and coaches. Community leaders can be effective channels because they influence other people and can influence policy. They disseminate messages broadly to groups or become part of an interpersonal channel. For example, in many Islamic countries, the Friday prayer and speech is a powerful way to introduce anti-tobacco messages through religious leaders. Developing relationships with, and creating messages and materials for, interpersonal channels may take some time, but these channels are among the most effective, especially for affecting individual attitudes, skills, and behavior/ behavioral intent. These channels are more likely to be trusted and influential than are mass media sources. Influence through interpersonal contacts may work best when the person is already familiar with the message, for example, after hearing it through the mass media.

Health professionals in most countries are in a good position to provide credible information on tobacco control issues. In China, where there is currently no ban on smoking in public places, physicians at Beijing’s United Family Hospitals and Clinics give pregnant women a brochure that identifies restaurants with smoke-free sections, or that are smoke-free all together, to encourage them to choose smoke-free environments. The brochure also requests that patrons give the brochure to restaurants that are not smoke-free to “see what their competitors are doing.” The brochure outlines what the restaurant will do to be smoke-free and provides some basic information about the dangers of secondhand smoke.††

Community and organizational channels can reinforce and expand on other media messages and add credibility and legitimacy. Community groups and organizations can disseminate your materials, hold events and offer instruction related to your message. Establishing links with these groups can be a shortcut to developing interpersonal channels to your audience(s). Also, garnering the support of many organizations that work together toward a common goal can create a positive momentum for your efforts.

• • • •

Global Dialogue Campaign Tool Kit

Mass media channels—radio, television, magazines, direct mail, billboards and newspapers—offer many opportunities for dissemination of a message. Possibilities include mentions in news programs; entertainment programming

(“entertainment education”); public affairs, “magazine,” and interview shows (e.g., radio call-in programs); live remote broadcasts; editorials on TV and radio and in newspapers and magazines; health and political columns in newspapers and magazines; posters; brochures; paid advertising; and public service advertising (PSAs). You may decide to use a variety of formats and media channels, but you should choose the ones that are most likely to effectively reach and influence your audience(s). Research has demonstrated that mass media approaches are effective in raising awareness, stimulating an audience to seek information and services, increasing knowledge, changing attitudes, and even

achieving some change in behavioral intentions and actual behaviors. However, behavior change is usually associated with long-term, multiple-intervention programs, rather than with one-time, communications-only campaigns.2 Mass media campaigns also can contribute to changes in social norms and to other collective changes, such as policy and environmental changes.

Interactive and electronic media channels, such as Web sites, Internet bulletin boards, newsgroups, podcasts, chat rooms and email messages, may be useful in your campaign. These media channels allow the delivery of highly targeted messages via email, the posting of information about health-related campaigns on popular Web sites, the exchanging of ideas and ready-to-use materials, and the means of rallying support for a policy or issue. Before choosing an

interactive channel, you will need to determine whether it is accessible and whether your audience is comfortable with the method.

Web blogs are online diaries that are used by individual users and by marketers. Web sites such as www.myspace.com, www.youtube.com, or www.wikipedia.com offer users the opportunity to post free content on the Web.

Using a combination of channels not only improves your chances of reaching more members of your audience(s), but also can increase the chance that the audience will be exposed to the messages often enough to internalize them.4 For example, physician recommendations may be persuasive to smokers but may not reach many people; TV ads may reach many people but may not be as credible as physicians’ recommendations. Some messages may seem more credible when they come from several sources or channels.

Consider the following as you select channels for your program: Choose channels that suit your objectives.

Where can you reach audience members?

When are they most likely to be attentive and open to your efforts? If action is an objective, where can they act on your message?

In which places or situations will they find your messages most credible and influential? Which places or situations are most appropriate for the approaches you are considering? Consider the attributes and limitations of each type of channel.

Select channels and activities that fit your budget, time constraints and resources. • • • • • • • • 2.6

St

ra

te

gi

c P

la

nn

in

g

2

Reality-Based Campaign:

United States

Glaxo SmithKline (GSK) recognized that smokers needed to hear from other smokers, or those who have recently quit, about quitting, and thus changed its campaign approach for CommitTM lozenges. Building on the popularity of “reality TV” shows, GSK gave smokers video cameras to tape themselves narrating their effort to quit during a 3-week period. The tapes were edited by professionals to be shown on television, on the Internet and in a movie-length documentary to be submitted to film festivals. GSK checked in with the quitters periodically to see how they were doing. As long as they remained committed

4c) Draft Program Strategies.

A strategy is the approach you plan to take with a specific audience. Although you may develop many different materials and use a variety of activities, your strategy documents should guide all your products and activities. A strategy includes everything you need to know to work with your audience. It defines the audience, states the action you want audience members to take, tells how they will benefit (from their perspective), and explains how you can reach them. The strategy is based on knowledge of the audience, guided by market research and theories and models of behavior, and affected by the realities of organizational roles, resources and deadlines.

Develop a strategy statement that explains what you will do. Then, make sure all key decision makers agree with it. You may be tempted to skip this step, but please do not. Having an approved strategy statement will save you time and effort later. Developing the statement will reveal whether you have enough information to begin developing messages and interventions. Explaining your plan to your organization and partners will help persuade them to buy into your program. The statement will also serve as the guideline for all your materials and activities.

At this stage in the planning process, you should involve experts in advertising, media advocacy, marketing or related fields, depending on the approaches you have selected. If you are working with partners, they might be a part of this campaign design team. Evaluation experts, if they are not already involved, also should join the team at this point. When writing your strategy statement, it is a good time to make sure you have the budget and other resources for the approaches and channels you have selected. Limiting your activities and doing fewer things well is more effective than stretching modest resources across many strategies, channels and targets. You may want to start with one target audience and one approach and add other elements in future years. For each of your target audiences, write

a strategy statement that includes the following elements.

Target audience profile. Try describing one person in the audience, rather than the group. The information you gathered in Step 2 should be useful here.

Action you want the audience to take as a result of exposure to your campaign. The action should be based on the objectives you drafted in Step 3.

Obstacles to taking action. Common obstacles include audience beliefs, social norms, time or peer pressures, costs, ingrained habits, misinformation, tobacco industry influence, and lack of access to products, services or program activities. The additional information you gathered about the audience in Step 2 should help you identify obstacles.

•

•

Global Dialogue Campaign Tool Kit

2.8

Benefit the audience will perceive as sufficiently valuable to motivate action. Many theories and models of behavior change suggest that people take action or change their behavior because they expect to receive some benefit (have more energy, save money, live longer or gain acceptance from peers) that outweighs the cost (time, money, withdrawal symptoms or potential loss of stature among peers).

Reason(s) the benefit and the audience’s ability to attain the benefit should be credible and important to the audience (sometimes called the “reason to believe”). Support can be provided through hard data, peer testimonials about success or satisfaction, demonstrations of how to perform the action (if audience members doubt their ability), or statements from people or organizations the audience finds credible. Support should be tailored to the concerns of audience members about the action. For example, if they are worried that they cannot act as recommended, a demonstration of the behavior may give them the confidence to act. If they question why they should take the action or whether it will have the promised health benefit, hard data or statements from credible people or organizations may be effective. If they do not believe they need to take the action, a peer testimonial may make them reconsider.

Channels and activities that will reach audience members.

The image you plan to convey through the tone, look and feel of messages and materials. You should convey an image that convinces audience members that the communication is directed at them and that it is culturally appropriate. Image is expressed largely through creative details. For example, printed materials convey image through typeface, layout, visuals, color, language and paper stock. Audio materials convey image through voices, language and music. In addition, video materials convey image through visuals, the actors’ characteristics such as tone of voice and age, camera angles and editing.

Developing a strategy is an evolving process; as you learn more about one element, other elements may need to be adjusted.

4d) Develop a Logic Model.

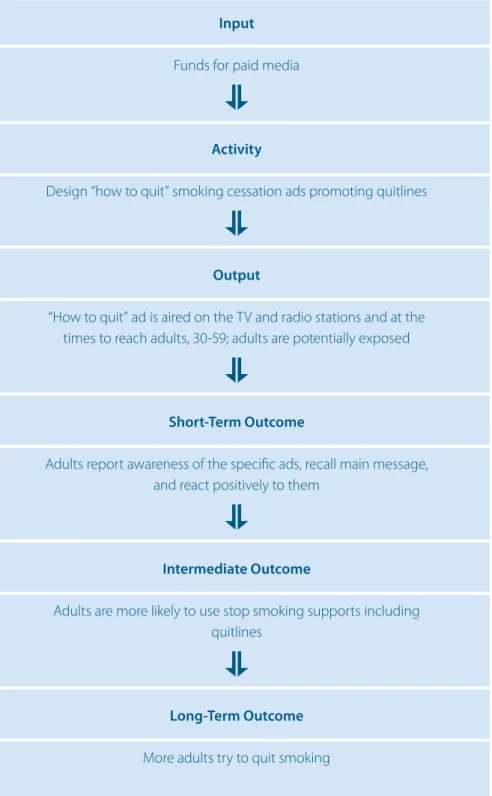

A logic model describes the sequence of events that will occur to bring about the change you have identified. This model is often designed as a flowchart (see Figure 2.) and is also useful in evaluation. A logic model is valuable because it:

Summarizes program components and outcomes at a glance. Displays the infrastructure needed to support the campaign. Forces you to describe what you are planning in a simple way. Reveals any gaps in the logic behind your plans.

Describes what will happen over the course of your campaign, which will be useful for working with stakeholders, partners and evaluators.

If you have identified several objectives and target audiences, you may need to develop several logic models. A logic model should include:

Inputs – what is necessary to conduct the program. Activities – what you will do.

Outputs – what will happen as a result of activities. Outcomes – results. • • • • • • • • • • • • •

St

ra

te

gi

c P

la

nn

in

g

2

Figure 2.1: Example of Logic Model for Stop Smoking Advertising Campaign

1Input

Funds for paid media

Activity

Design “how to quit” smoking cessation ads promoting quitlines

Output

“How to quit” ad is aired on the TV and radio stations and at the times to reach adults, 30-59; adults are potentially exposed

Short-Term Outcome

Adults report awareness of the specific ads, recall main message, and react positively to them

Intermediate Outcome

Adults are more likely to use stop smoking supports including quitlines

Long-Term Outcome

Chapter

Step 5: Where Can You Get Help?

Working with other organizations can be a cost-effective way to enhance your program’s credibility and reach. Think about partnerships with businesses, government agencies, volunteer and professional organizations, schools and community groups, the mass media, or health-related institutions. These organizations can help you by providing:

Access to a target audience.

Enhanced credibility for your message or program because the audience considers the organizations to be trusted sources.

Additional resources, either financial or in-kind resources (volunteers, meeting space or media placements). Added expertise (i.e., training capabilities).

Co-sponsorship of events. • • • • •

2.20 Global Dialogue Campaign Tool Kit

Collaboration Among

Diverse Partners:

Multiple Countries

The Global Dialogue for Effective Stop Smoking Campaigns began in January 2005 as a unique collaboration between public, private and non-profit organizations, all linked by the shared interest in decreasing smoking prevalence by maximizing the impact of public education campaigns. Every partner organization in the Global Dialogue initiative has committed to contributing funds, staff time or other in-kind products or services to further the goals of the initiative through specific projects. Partners contribute time to monthly conference calls, as well as to individual projects, and each year about half of the partners contribute funds toward the initiatives based on their own objectives and financial commitments. Some partners have contributed meeting space, training resources, international contacts or sample documents. Other partners have contributed funds for specific uses such as administrative costs, meeting and conference planning, tool kit development or a literature review.

For more information about Global Dialogue, visit: http://www.stopsmokingcampaigns.org.

5a) Decide Whether to Collaborate.

Consider these questions:

Which organizations have similar goals and might be willing to work with you?

Which types of partnerships would help to achieve the campaign’s objectives?

How many partners does your campaign need? You might want to partner with one or a few organizations for specific projects, or you may need to gain the support of many organizations. Will the collaboration compromise your messages?

Although working with other organizations and agencies can greatly enhance what you can accomplish, there are potential disadvantages of collaboration. Working with other organizations can:

Be time consuming. You will have to identify the organizations, persuade them to work with you, gain internal approvals, and coordinate planning, training or both.

Require changing your campaign. Every organization has different priorities and perspectives. Partners may want to make minor or major changes to accommodate their structure or needs. Result in loss of control of your campaign. Other organizations may change the schedule, functions, or even the messages and take credit for the campaign. Decide in advance how much flexibility you can give partners without violating your campaign’s integrity and direction, and your own organizational procedures. • • • • • • •

St

ra

te

gi

c P

la

nn

in

g

2

5b) Consider Criteria for Participation.

Once you decide to partner with other organizations, be selective in choosing partners. Consider which organizations meet the following criteria:

Would best reach your audience(s).

Are likely to have credibility and influence with your audience(s).

Would be easiest to persuade to work with you (organizations where you have good relations or at least a contact). Would require less support or fewer resources from you.

Health care companies and other for-profit organizations may be willing to work with you even if their products or services are not directly related to your campaign. They may view partnering with your program as a way to provide a useful public service, improve their corporate image and credibility, or attract the attention of a particular sector of the public. You must consider whether a collaboration of this type will add value or jeopardize the credibility of your program.

Step 6: How Will You Know What You Achieve?

Evaluation is crucial for showing funding sources, partners, supporters and critics what you have achieved. Evaluation can be an expensive part of your campaign budget. While it is always critical to undertake a high-quality evaluation, when resources are tight it is sometimes necessary to make difficult decisions about priorities. Understanding the purpose of your evaluation will help you to understand the level of resources and sophistication that you should devote to your evaluation. For example, if the purpose of your evaluation is to understand the effectiveness of your campaign for internal program improvement, you will conduct a different evaluation than if you need to demonstrate campaign effectiveness to government leaders to ensure campaign funding, or for publication in scientific journals.

One of the crucial issues to understand about evaluation as you are planning the strategic focus of your campaign is that you must plan for your evaluation at an early stage to ensure that you have the budget and infrastructure to gather and analyze the information you will use.4 In addition, you will probably want to conduct a baseline study of the target audiences’ current awareness, knowledge, attitudes and behaviors. You will be able to determine the campaign’s impact by comparing post-campaign results with the same measures from the baseline study. Planning for the baseline study must be done early enough to implement the research before the campaign begins. See Chapter 5: Campaign

Evaluation for more information about evaluations and how to conduct campaign evaluations. •

• • •

Global Dialogue Campaign Tool Kit

Conducting Evaluation

with Limited Resources

Organizations often use external evaluation firms to conduct campaign evaluations to ensure that the evaluation is conducted without the appearance of any bias. While it is advisable to hire external professional evaluators, some organizations may not be able to afford them. In this case, it is still important to do an evaluation of your campaign. Here are some suggestions for conducting an evaluation when there are few resources available:

Partner with a university or research organization to conduct the evaluation. There may be a doctoral student at the university who can use the campaign evaluation as excellent practical experience.

Leverage your resources. Approach an evaluation firm with the resources that you have available for the evaluation of your campaign. They may be able to advise you on how to effectively use your funding to get the most from your evaluation budget, with external agencies responsible for some of the work and your organization responsible for other aspects. Separate evaluation components. If you are using internal evaluation staff, make sure that their roles and functions are separate from the campaign so that there is as little organizational influence as possible between the groups.

Have an external evaluation expert review the evaluation plan. This will not mean that stakeholders will believe it to be as credible as if the evaluation were conducted by an external team, but it will build credibility that the plan is appropriate.

Gain advisory approval. Your stakeholders need to understand the strengths and limitations of your evaluation. Make sure that they approve the evaluation plan and understand what it will, and will not, be able to say about your campaign. • • • • • 2.22

St

ra

te

gi

c P

la

nn

in

g

2

Step 7: What Are the Next Steps?

Now you are ready to start developing your campaign. Campaign development and management are discussed more fully in Chapter 6: Campaign Management. Here are some key points:

Develop a communications plan for stakeholders (those who are interested in or have a stake in your campaign) that includes all the elements of your planning. It should explain your plan; support and justify budget requests; provide a record of where you began; and show the campaign’s planned evolution.

Create a budget and a timeline that assigns tasks and identifies deadlines. In the timeline, plan for testing

messages, developing materials, organizing activities, negotiating partner roles and conducting a campaign review for stakeholders.

Find out about similar campaigns in other regions and consider using their “lessons learned” and any messages and materials they have developed. See the Global Dialogue Web site, http://www.stopsmokingcampaigns.org, for examples. Free registration is required.

Conduct the market research needed to understand more about your target audience’s culture, motivations, interests and lifestyle.

Begin to develop campaign components. For guidance, see Chapter 7: Advertising, Chapter 8: Public Relations,

Chapter 9: Media Advocacy and Chapter 10 : Community-Based Marketing.

The timeline should include every major task from the time you write the plan until the time you intend to complete the campaign. The more tasks you build into the timetable, the more likely you will remember to assign the work and stay on schedule. Also, detailing the tasks will make it easier to determine who is responsible for completing tasks and what resources will be required. You may want to review and update the timeline regularly so you can manage and track progress. Computer-based tools, such as project management software, can be especially useful for this task. For a sample of a campaign summary from Canada, see Appendix 2.3.

Points to Remember

Planning is an integral step. Do not skip it! Effective planning will help you:

Better understand the tobacco control issue you are addressing. Identify the most appropriate approaches to cause or support change. Create a tobacco control campaign that supports clearly defined objectives.

Your campaign plan should complement your organization’s broader tobacco control effort and overall plan. Many of the planning activities in this chapter can be completed simultaneously.

A strategic plan is a living document. As the campaign progresses, review the plan to clarify and revise it as needed. Be prepared to evaluate what you do.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • •

Global Dialogue Campaign Tool Kit

2.24

Bibliography

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Designing and Implementing an Effective Tobacco Counter-Marketing Campaign. Atlanta, Ga.: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2003. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/media_communications/countermarketing/campaign/00_pdf/Tobacco_ CM_Manual.pdf. Accessed March 30, 200.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDCynergy for Tobacco Prevention and Control. Atlanta, Ga.: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2003.

Backer TE, et al. Designing Health Communication Programs: What Works? Newbury Park, Calif.: Sage Publications; 992.

National Cancer Institute. Making Health Communication Programs Work: A Planner’s Guide. Bethesda, Md.: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health; 2002. NIH Pub. No. T068.

National Cancer Institute. Theory at a Glance: A Guide for Health Promotion Practice. 2nd ed. Bethesda, Md.: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health; 2005. NIH Pub. No. 95-3896.

The Communication Initiative. The change theories page. Available at: http://www.comminit.com/changetheories. html. Accessed March 30, 200.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Global Youth Tobacco Survey. Atlanta, Ga.: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2000. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/global/ GYTS/factsheets/paho/2000/chilesantiago_factsheet.htm. Accessed March 30, 200.

World Health Organization. Waterpipe Tobacco Smoking: Health Effects, Research Needs and Recommended Actions by Regulators. WHO Document Production Services: Geneva, Switzerland, 2005.

Chaaya M, El-Roueiheb Z, Chemaitelly H, Azar G, Nasr J, Al-Sahab B. Argileh smoking among university students: a new tobacco epidemic. Nicotine Tobacco Research. 2004 Jun;6(3):45-63; Maziak W, Ward KD, Afifi Soweid RA, Eissenberg T. Tobacco smoking using a waterpipe: a re-emerging strain in a global epidemic. Tobacco Control. 2004; 3: 32-333.

Ward et al. The tobacco epidemic in Syria. Tobacco Control. 2006; Jun 5 Suppl :i24-9.

Snyder LB, Hamilton MA. A meta-analysis of U.S. health campaign effects on behavior: Emphasize enforcement, exposure, and new information and beware the secular trend. In: Hornik RC, ed. Public health communication: Evidence for behavior change. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2002:32–56.

Smith W. From prevention vaccines to community care: new ways to look at program success. In: Hornik RC, ed.

Public health communication: Evidence for behavior change. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2002:32– 56.

Story L. Kicking an addiction, with real people. The New York Times. 200; Jan. 2.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Framework for program evaluation in public health. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 999;48(RR–):–40. Atlanta, Ga.: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health.

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14.