SERVICES IN KENYA II

Lucy Anne Wanjiru aweru Bsc. (Family and Consumer Sciences) Reg. No. 157/11031104

A research thesis submitted for the award of the degree of Masters of Public Health in the School of Health Sciences of Kenyatta University

October, 2009

Waweru, Anne Wanjiru Effectsof

intergration of

1

1111

I!

IIIIII~ IIIIIIIIIIIIII~IIII

2011/357617

DECLARATION

This thesis is my original work and has not been presented for a degree or any other award in any other University.

Lucy Anne Wanjiru Waweru 157/11031/04

Signature ~~

SUPERVISORS' APPROVAL

This thesis has been submitted for review with our approval as University supervisors

Dr Margaret Keraka

Department of Public Health Kenyatta University

Signature __

----'

~

~=_=

_

__·

__

~

_

tt

Dateq

__

f_l_t_l_(

)

_9

__

Dr B.M Okello Agina Department of Public Health Kenyatta University

S;gnaWr

~'

-G

\J.-

a

~~

Date

cy \\\

l=7-J"DEDICATION

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Let me express my heartfelt appreciation to my supervisors Dr Margaret Keraka and Dr B.M Agina Okello for their invaluable guidance, counsel, suggestions, critical comments and encouragements during the writing of my thesis. Many thanks to Dr David Kiragu, Dr Naftali Oirere in addition to the members of staff of the Department of Public Health of Kenyatta University for their continued support. Special thanks go to Dr Joachim Osur and community of Family Health Options Kenya for creating a conducive environment for the study to be carried in. In addition to the members of staff and clients who took part in study in Nairobi-west and Thika Family Care Medical Clinics.

My appreciation goes to all my friends for their friendship, support and encouragement throughout the study period. I am greatly indebted to my parents, Miriam and Michael Waweru, my husband Julius Karuga and siblings for their prayers, support, and encouragement and for being my role models. Lastly to the Almighty God for granting

me sound health, wisdom, strength and grace to go through my Masters education. In addition to providing the resources that were required to facilitate my education.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

TITLE i

DECLARATION ii

DEDICATION .iii

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT iv

TABLE OF CONTENT v

LIST OF FIGURES .ix

LIST OF TABLES x

OPREATIONAL DEFINITION OF TERMS xi

ABBREVIATIONS AND ACROYNMS xii

ABSTRACT xiv

INTRODUCTION 1

1.1Background 1

1.2 Statement of the Problem 5

1.3 Justification of the Study 6

1.4'Research Questions 8

1.5 Null Hypothesis 8

1.6 Objectives 8

1.6.1 Broad Objective 8

1.6.2 Specific Objectives 8

1.7 Significance and Anticipated Output.. 9

CHAPTER TWO 14

LITERATURE REVIEW 14

2.2 Reproductive Health Services 14

2.3 Care for People Living With HIV and AIDS 15

2.4 Integration of Reproductive Health Services and HIV and AIDS Care 17

CHAPTER THREE 33

MATERIALS AND METHODS 33

3.1 Research Design 33

3.2 Variables 33

3.3 Location of the Study 35

3.4 Target Population 36

3.5 Study Population 37

3.5.1 Criteria for Inclusion 37

3.5.2 Criteria for Exclusion 37

3.6 Sampling Techniques and Sample Size : 38

3.6.1 Sampling Techniques 38

3.6.2 Sample Size Determination for Clients 38

3.7 Construction of Research Instruments 40

3.8 Pilot Study 40

3.8.1 Validity 41

3.8.2 Reliability 41

3.9 Data Collection 41

3.11 Logistical and Ethical Considerations 42

CHAPTER FOUR 44

DATA ANALYSIS, RESULTS AND DISCUSSIONS 44

4.1 Introduction 44

4.2 Socio-Demographic Characteristics of Study Population 44

4.3 Reproductive Health Services Utilized by Respondents 46

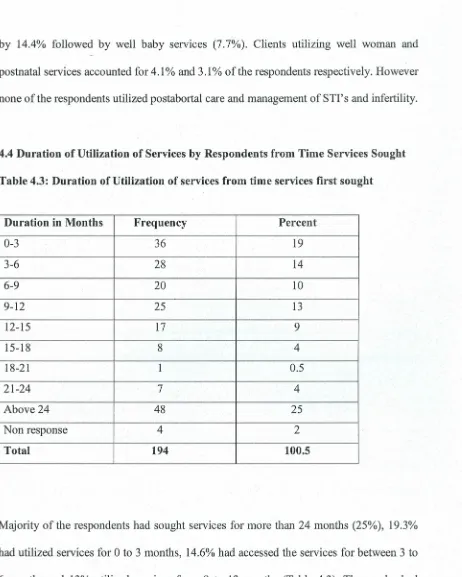

4.4 Duration of Utilization of Services by Respondents from Time Services

Sought 47

4.5 Reasons for Seeking Services from the Clinics 48

4.6 Utilization Patterns of Reproductive Health Services before Integration 48 4.7: Changes in Uptake of Reproductive Health Services Following Integration 50

,

4.8 Effects of Integration on the Utilization of Reproductive Health Services 54

4.8.3 Quality of Integrated Services 57

4.8.7 Work Load : 61

4.9 Factors affecting the Utilization ofIntegrated Services 61 4.9.1 Utilization Patterns of Integrated Services 61

4.9.3 Awareness of Availability ofHIV/ AIDS Related Services 63

4.10 Socio-Cu1tural Factors 66

4.11. Cost of Integrated Services 67

CHAPTER FIVE 70

SUMMARY, CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATION 70

5.2 Implication of the Findings 70

5.5 Recommendations 72

5.6 Areas for Further Research 73

REFERENCES , 74

Research Instrument. 77

7.4.1 Consent Form 77

Clients Questionnaire 78

LIST OF FIGURES

FIGURE PAGES

Figure 1.0 Conceptual Framework. 13

Figure 4.1 Quality of Integrated Services 56

Figure 4.2 Changes in Quality of Services after Integration 57

Figure 4.3 Utilization Levels of HIV and AIDS Related Services 60

LIST OF TABLES

TABLE

Table 2.0 Adding Family Planning to VCT Levels of Integration in Kenya .

Table 2.1 Potential Benefits and Challenges of Integration .

Table 4.1 Socio-Demographic Characteristic of Study Population .

Table 4.2 Reproductive Health Services Utilized by Respondents .

Table 4.3 Duration of Utilization of Services from Time Services First Sought.

Table 4.4 Utilization Patterns of Reproductive Health Services in Nairobi-West and Thika Family Care Medical clinic before Integration .

Table 4.5 General Changes in Uptake of Reproductive Health Services

following Integration .

Table 4.6 Changes in Utilization of Reproductive Health Services in

Nairobi-West Family Care Medical clinic following Integration .

Table 4.6.1 Changes in Utilization of Reproductive Health Services in Thika

Family Care Medical Clinic .

Table 4.7 Acceptance ofIntegration by Clients .

Table 4.8 Modes of Creating Awareness of Availability of HIV and AIDS

Related Services to Clients .

Table 4.9 Cost of Integrated Services .

Table 4.10 Changes on the Cost of Services after Integration .

OPERATIONAL DEFINITION OF TERMS

Reproductive health services: These are techniques and services that contribute to

reproductive health and well being by preventing and

solving reproductive health problems.

Comprehensive HIV/AIDS care: Focused care that meets patients' physical, social, psychological, emotional and spiritual needs.

Integration: Offering two or more services at the same facility,

during the same operating hours with the provider of one

service actively encouraging clients to consider using

the other services during the same visit.

Clients: Refers to women within the reproductive age bracket

(15-49 years) seeking reproductive health from the

clinics under study.

Service providers:

Refers to the short-term results or outcome of

integrating HIV and AIDS care into reproductive health

services and it can either be positive or negative.

Refers to the member of the medical clinics health facilities offering reproductive health services.

Effects:

Accessed: The utilization of reproductive health and HIV and

AIDS services that had been integrated. Synonymous to

AIDS ARBEF ARV CBOs EGPAF FBOs FGM FHI FHOK HIV NGO OVCs PLWHA PMTCT STI VCT ZNFPC

ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS

Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome

Association Rwandaise pour Ie Bien-Etre Familial

Antiretroviral

Community Based Organizations

Elizabeth Glaser Pediatric AIDS Foundation

Faith Based Organizations

Female Genital Mutilation

Family Health International

Family Health Options Kenya

Human Immune Deficiency Virus

Non-Governmental Organizations

Orphans and Vulnerable Children

People Living With HIV/AIDS

Prevention of Mother to Child Transmission

Sexually Transmitted Infections

Voluntary Counseling and Testing

ABSTRACT

CHAPTER ONE

INTRODUCTION

1.1 Background

Sub-Saharan Africa bears the largest burden of HIV and AIDS. In the year 2004, an

estimated 3.1 million people became infected, while 2.3 million people died of AIDS

almost 75% of deaths globally (UNAIDS, 2004). In 2005, Sub-Saharan Africa accounted

for 64% of the 5 million people who became newly infected with the HIV and AIDS

globally (UNAIDS, 2005). During 2006, around 4 million adults and children became

infected with HIV and AIDS. An estimated 39.5 million people were living with HIV and

AIDS globally with around 63% of PLWHA's living in Sub-Saharan Africa. The year

also saw around 3 million deaths from HIV and AIDS despite recent improvement in

access to antiretroviral treatment (UNAIDS 2006). Like many other parts of the world,

this region faces a rapid feminization of the epidemic. In Kenya, HIV and AIDS is still a

burden with 1.4 million people living with HIV. According to the results of the 2007

Kenya Aids Indicator Survey, 7.4% of adults aged 15-64 are infected with HIV, with

high HIV infection rates registered among old adults aged 50-64 years (KAIS,2007).

HIV and AIDS is disproportionately affecting women and girls. This is aggravated by

social and economic inequalities between men and women. Women and girls commonly

face discrimination in terms of access to education, employment, credit, health-care, land

and inheritance in addition to their biological vulnerability. These factors put women in a

position where they are particularly vulnerable to HIV and AIDS infection (UNAIDS

heterosexually, the vulnerability of women is increased by the fact that in many African

countries, sexual relationships are dominated by men as such women cannot always

practice safe sexs even when they know the risks involved (UNAIDS, 2006). Until an

effective and affordable vaccine or microbicide is developed they lack the means within

their control to prevent HIV/STI infection (UNAIDS, 2006). When women fall ill, their

families lose their primary care giver and often a primary bread winner. The women who

die leave behind millions of orphans. Meanwhile other sexually transmitted infections

remain both a cofactor in the spread of HIV and AIDS and a major problem in their own

right with an estimated 340 million new cases of STI's annually (WHO, 2003).

The gap in HIV and AIDS prevalence between men and women continues to grow. In

the year 2006, in Sub-Saharan Africa around 59% of those living with HIV and AIDS

were women. Many more young girls than young men are affected due to lack of access

to HIV and AIDS prevention services which leave them at risk for themselves and their

unborn children. In many countries of Southern Africa, one in five pregnant women is

infected with HIV and most children contract HIV and AIDS from their mothers (FHI,

2005). In 2005, an estimated 4.6% of women were living with the virus against 1.7%of

men living (UNAIDS, 2005). As is the case in many African countries, HIV prevalence

in Kenya is higher among women (8.7%) than among men (5.6%). According to the

results of Kenya Aids Indicators Survey released in 2007, young women between 15 and

34 years are more likely to have HIV in comparison to young men of the same age group.

Majority of the women infected with HIV come into contact with the health-care delivery system seeking reproductive health services. They do seek' the services either within clinical settings or through community based distribution programs. Reproductive health providers serve millions of women in developing countries now at the centre of global

HIV and AIDS pandemic (AGI and UNPF, 2003). Some half a million women in developing countries use a modem contraception method. Majority of pregnant women make at least one visit for prenatal care during pregnancy and a significant proportion of women make at least one post-natal clinic visit (AGI and UNPF, 2003). According to the Kenya Demographic Health Survey carried out in 2003 by Central Bureau of Statistics, 31% of women are on a modem method of contraception; about 90% of pregnant women make at least one antenatal visit, while post-partum care is accessed at least once by 42% of women, thus extending access to infants. Other reproductive health services that women seek from the clinics are well-baby, well-woman, management of STI's, management of infertility and lastly post-abortal care. For these reasons, the clinics and Community Based Distribution programs create opportunities to reach women with HIV and AIDS prevention information and services (AGI and UNPF, 2003).

solid base upon which stepped up interventions for HIV and AIDS prevention and

management can be built. These areas are counseling and advice about sexual health,

skills in communication with defined groups, sexual education for young people,

programs concerned with women's role in development, contraceptive counseling

especially valuable for PLWHA's and management of STI's. As such they are poised to

play an important role in reducing the incidents of HIV and AIDS infections over the

coming years. Policy makers, donors, researchers and activists should recognize the

benefits of supporting the fuller integration of HIV and AIDS prevention efforts with

reproductive health services (AGI and UNFPA, 2003).

All these in addition to the shift of focus at the beginning of 21stCentury to provision of

integrated reproductive health and HIV and AIDS services formed the basis for

integration to be implemented in Family Care Medical Centers managed by Family

Health Options Kenya (FHOK). FHOK formerly Family Planning Association of Kenya

is the pioneer of the family planning movement in Kenya. It was legally registered in

Kenya and affiliated to the International Planned Parenthood Federation (IPPF) in 1962.

The integration was implemented in four Family Care Medical Centers. The four,

Nairobi-West, Thika, Nakuru and Eldoret Family Care Clinics were selectively upgraded

for the introductory phase of the integration, which is more than four years old. The

integration has been rolled out to remaining four of the Family Care Medical Clinics

namely Kisumu, Rebeiro, Phoenix and Meru. It is anticipated that after the integration is

However the effects of the integration on the uptake of reproductive health services are

yet to be established since in most settings the two services are offered independently.

1.2 Statement of the Problem

In most settings in the world, reproductive health and HIV and AIDS services have been

offered separately with little or no integration. Reproductive health services primarily

target married women of reproductive age bracket while HIV and AIDS services target

individuals at high risk of HIV infection (Foreit et al., 2002). However the potential

benefits of integrating these services are increasingly apparent as ever more women of

reproductive age become infected with HIV and AIDS or at risk of infection (Foreit et

al., 2002). In developing countries about half of the 40 million people now living with

HIV and AIDS are women of reproductive age with percentage approaching 60% in

some African countries. The potential of reproductive health service providers reaching

women who accounted for nearly half of all adults living with HIV and AIDS with HIV

prevention, information (UNAIDS 2004). In addition to a ready infrastructure which is as

a result of donors and government investing heavily in reproductive health services over

the last three decades and services (AGI and UNFPA, 2003).

This has resulted to many types of integrations being explored but their effects on

. reproductive health services have not been rigorously evaluated and largely unknown.

Research is essential to assess the effects of integration on service quality, acceptability,

this that this study was carried in selected Family Care Clinics that have implemented the

integration of services.

1.3 Justification of the Study

Majority of HIV and AIDS infections are sexually transmitted or associated with

pregnancy, childbirth and breastfeeding. The interactions between reproductive health

and HIV and AIDS are widely recognized. Most of HIV infected persons are within

reproductive age, 63% of all HIV and AIDS cases are in Sub-Saharan Africa with women

accounting for 60%, 75-80% of all HIV and AIDS infections in this region are

transmitted heterosexually, with women and youth being most vulnerable (UNAIDS

2006). In addition, reproductive ill-health and HIV and AIDS share root causes including

poverty, gender inequality and social marginalization of the most vulnerable population

(UNFP A, 2005) The international community agrees that the Millennium Development ~

Goals will not be achieved without ensuring access to reproductive health services and an

effective global response to HIV and AIDS ( UNFPA,2005). This can be achieved

through the integration of services.

The integration of HIV and AIDS and reproductive health services creates a number of

important synergies. When programs offer clients the chance to meet multiple needs,

either within the same visit or via referral, they are more likely to achieve these important

health goals. Integrated services or better linkages may promote reaching broader groups

with information and services that are not typically reached in a particular vertical

reproductive health services like family planning services. However the unmet need for

these services is often greatest in countries with high HIV and AIDS prevalence (Myaya,

2004). These needs can be better met if the reproductive health services are offered where

such women access HIV and AIDS services.

Meanwhile clients accessing reproductive health services may well need HIV and AIDS

prevention, diagnosis and treatment services. Many of these clients are married women

who are usually considered at low risk of HIV and AIDS infection (Altman, 2004). But

evidence from several countries suggest that marriage may offer women little protection

against HIV and AIDS infection since married women may have little or no power to

negotiate safe sexual practice with their husbands (Altman, 2004). Forty percent of new

infections in Thailand occur between spouses and 90% of those infections are

transmitted from husband to wife (Agence France Presse, 2004). For the integration to

be effective and realize the potential benefits; policies, conceptual frameworks and

legislative frameworks supporting the integration of services are required, rigorous

research is needed to expose the experiences of other sites integrating services, evaluate

the impact of other models of integration and identify effective models. This study will

generate findings that will be used to this end.

1.4 Research Questions

1. What were the utilization patterns of reproductive health services before integration of

HIV and AIDS care into reproductive health services?

2. What were the changes in the uptake of reproductive health services following

integration HIV and AIDS care into reproductive health services?

3. What were the effects of integration of HIV and AIDS care into reproductive health

services on the utilization of reproductive health services?

4. What were the factors determining the utilization patterns of the integrated services?

1.5 Null Hypothesis

1. Integration of HIV and AIDS care into reproductive health services does not affect the

utilization of reproductive health services.

1.6 Objectives

1.6.1 Broad Objective

1. To determine the effects of integration of HIV and AIDS care into reproductive

health services on the utilization of reproductive health services.

1.6.2 Specific Objectives

1. To determine the level utilization of reproductive health services that were offered

before integration of HIV and AIDS care into reproductive health services

2. To find out the changes in the uptake of reproductive health services following

3. To establish the effects of integration of HIV and AIDS care into reproductive

health services on the uptake of reproductive health services.

4. To determine the factors contributing to the utilization patterns of integrated

services

1.7 Significance and Anticipated Output

The AIDS epidemic is integrally linked to sexual and reproductive health. The majority

of HIV infections are sexually transmitted or associated with pregnancy, childbirth and

breastfeeding (UNFPA, 2009). Both HIV and AIDS and poor sexual and reproductive

health are driven by common root causes including poverty, gender inequality and social

marginalization of the most vulnerable populations. Responses to both health issues

should be closely linked and mutually reinforcing (UNFP A, 2009). UNFPA, along with

the rest of the international community, strongly advocate for closer linkages between

HIV and AIDS interventions and sexual and reproductive health care. This makes sense

in terms of public health benefit, economic efficiency and human rights. Integration of

services was called for at the 2005 World Summit when leaders identified universal

access to reproductive health as a combating HIV and AIDS and achieving the other

Millennium Development Goals (UNfP A, 2009).

The integration between reproductive health and AIDS programme should lead to a

number of important public health benefits:

• Improved access to, and uptake of key services.

• Reduced A}DS- related stigma and discrimination.

• Improved coverage of under served and marginalized populations such as injecting

drug users, sex workers or homosexuals.

• Greater support for dual protection against unintended pregnancy and STls

including HIV, for those in need, especialiy young people.

• Improved quality of care.

• Enhanced programme effectiveness and efficiency.

The investigation of effects of integration of HIV and AIDS Care into reproductive health

service on the utilization of reproductive health services is becoming increasingly

important. This is as a result of the shift of focus at the beginning of 21st century from

vertical programmes to integrated programmes. The shift in focus has led to many types

of integrations being explored and or implemented. Integrated services would be

convenient, perhaps a lifesaver to individuals who have limited access to sexual and

reproductive health care (UNFP A, 2009).

In Sub-Saharan Africa, where the HIV and AIDS epidemic is widespread, almost 61%of

women were living with HIV in 2007 (UNAIDS 2007). Majority of whom have unmet

need for effective contraceptive and consequently a high proportion of unintended

pregnancies. Many of these women do not know their HIV status, have limited access to

information and services thus risk to passing the virus to their children (UNFPA, 2009).

Under these circumstances, access to even a minimal integrated package of care can

AIDS in addition to preventing HIV transmission to their children. Integration of HIV

and AIDS care and reproductive health services is one of many steps called for by the

Maputo Call to Action 'Plan'of Action on Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights'

(UNFPA, 2009). Therefore the integration of HIV and AIDS care and reproductive health

services in Thika and Nairobi-West Family Care Medical clinic can help in reversing the

feminization of HIV and AIDS in the Kenya. More so the integration will aid in meeting

the unmet reproductive needs of women.

1.8 Delimitation and Limitation of the Study

1.8.1 Limitations of the Study

The study was limited to only two of the four Family Care Clinics implementing the

integration due to a scarcity of resources. In addition, due to limited time the

retrospective and prospective study of services following integration was carried for a

short period of time as such yielding short term effects only. Respondents thought they

would be given a token of participation since there was a parallel study taking place in

one of the clinics where by participants were rewarded financially. As such they had to be

convinced to participate. Lastly there was a degree of non response from the respondents.

1.8.2 Delimitations of the Study.

The study focused on people both in the urban and rural set-ups of Nairobi-West and

Thika Town and their vicinities respectively. The findings were limited to Nairobi

Province and Thika District. The study established the short term effects of integration

-only. As such the findings should be generalized selectively in studies establishing long

term effects of integration.

1.9 Basic Assumptions of the Study

The following assumptions were made to serve as a guideline for the study;

• Integration of service had been fully implemented and yielded effects on the

existing reproductive health services, service providers and clients.

• Both the service providers and clients were aware that integration had been

implemented.

• Clients who utilized the services were aware of the effects of integration on

1.9 Conceptual Framework

Independent variable

Components of

comprehensive HIV/AIDS

Dependent variables

Reproductive health services

Expected outcome

.:.

VCT.:.

Family planning.:.

PMTCT.:.

Well baby clinicImproved

.:.

Ante-retrieval.:.

Well-womantherapy clinic access to and

.:.

Psychological care.:.

Antenatal clinic ---+uptake of key

.:.

Home based care.:.

Post-natal clinic.:.

Nutritional.:.

Post-Abortal care HIV/AIDS &counseling

.:.

Management ofReproductive

.:.

Management of STI'sopportunistic

.:.

Management of Health infections infertilityServices

Figure 1.0

Key

• -+Point of formation of Linkages and Interactions between the two sets of

services once the integration is fully implemented

Adopted from www. Unfpa.org/icpd/1 O/docs/hiv-aids-rh-call-commitment.doc

CHAPTER TWO

LITERA TURE REVIEW

2.1 Introduction

As the spread of HIV and AIDS has.spiraled into a pandemic, funds have been poured

into vertically structured efforts to combat the disease. HIV and AIDS is primarily a

sexually transmitted disease, separating prevention, care and treatment from reproductive

health context hampers long term prevention efforts and solution to reproductive health

issues related to HIV and AIDS. Hence the need for the integration of the two services to

counteract this (Moloney et al, 2003).

2.2 Reproductive Health Services

Reproductive health is a state of complete physical, mental and social well- being and not

merely the absence of disease or infirmity in all matters relating to the reproductive

system and to its functions and processes (Jay and Sharifar, 1994). Reproductive health

therefore implies that people are able to have a satisfying and safe sex life and that they

have the capability to reproduce and the freedom to decide if, when and how often to do

so. Implicit in this last condition are the rights of men and women to be informed and

have access to safe, effective, affordable and acceptable methods of family planning of

their choice, as well as other methods of their choice for regulation of fertility which are

not against the law. More so the rights of access to appropriate health care services that

will enable women go through pregnancy, child birth and provide couples with the best

chance of having a healthy infant (Jay and Sharifar, 1994). In line with the above

services that contribute to reproductive health and wellbeing by preventing and solving

reproductive health problems. It also includes sexual health, the purpose of which is the

enhancement of life and personal relations and not merely counseling and care related to

reproductive and sexually transmitted diseases (Jay and Sharifar, 1994). Although the

priority for specific reproductive health services will differ from country to country, the

following are the basic components of reproductive health; family planning counseling,

information, education and services, prevention and treatment of reproductive tract

infections including sexually transmitted infection, prenatal care, delivery, postnatal care

including breastfeeding and infant and women's health care, prevention and appropriate

treatment of infertility, prevention of abortion and post-abortal care and gynecological

services for women (Jay and Shari far, 1994).

According to World Bank, in the year 1993, about a third of the total disease burden in

women in developing countries is linked to health problems related to pregnancy, child

birth, abortion HIV/AIDS and reproductive tract infections. In addition problems such as

FGM malnutrition, unregulated fertility, osteoporosis and prolepses contribute to

women's ill health in their life cycle (Jay and Sharifar, 1994).

2.3 Care for People Living With HIV and AIDS

Treatment and care for HIV and AIDS consists of a number of different elements apart

from ARVs and indeed should be provided before ARVs are available. The care must be

comprehensive and continuous and not simply restricted to treatment (National

with not only physical but also social, psychological, emotional and spiritual care

(National AIDS/STD Control Program, 2005). Such comprehensive care encourages

disclosure of status, thus helping prevent on-going transmission, promote positive living,

promote good nutrition, encourage living a healthy lifestyle, manages opportunistic

infections and sexually transmitted infections medically, provides treatment with

antiretroviral therapy and lastly provide home-based care and end of life support

(National AIDS/STD Control Program, 2005). Home based care is the care of people

infected and affected by HIV and AIDS within the home and community, serving as a

link between hospital or health facility and the client' home through family participation

and community involvement (National AIDS/STD Control Program, 2005).

In Kenya, home based care is community based with most care provided by community

health workers, volunteers supported by clinicians, nurses, and spiritual counselors.

Quality home-based care has four main components; clinical care which entails early

diagnosis, prescribes rational treatment and plans for follow-up care of HIV related

illnesses, nursing care which promotes maintaining good health, hygiene and nutrition,

counseling and psycho spiritual care that helps reduce stress and anxiety, promotes

positive living and helps make informed decisions on testing for HIV, changing their

behavior and planning for the future and lastly social support which provides

information about support groups and welfare services and refers patient to them,

provides legal advice for individuals and families, including surviving family members

The most important entry point into the continuum of care is voluntary HIV counseling

and testing. The VCT is an important patt of any national prevention program. It is

widely recognized that individuals living with HIV and AIDS who are aware of their

status are less likely to transmit HIV infection to others and that through testing they can

be directed to care and support that can help them stay alive (UNAIDS, 2006). VCT also

provides benefit for those who test negative in that their behavior may change as a result

of the testing. The provision of VCT has become easier, cheaper and more effective as a

result of the introduction of the rapid HIV testing, which allows individuals to be tested

and get the results the same day (UNAIDS 2006). The testing and counseling is now

available through VCT, PMTCT, diagnostic testing and counseling in tuberculosis clinics

as well as out and in-patients department.

2.4 Integration of Reproductive Health Services and HIV and AIDS Care

Integration in the health sector has been defmed as offering two or more services at the

same facility during the same operating hours, with the provider of one service actively

encouraging clients to consider using the other services dwi.ng the same visit in order to

make those services more convenient and efficient (Foreit et al., 2002). In practice

integrated services are not always offered under one roof, but in such instances strong

referral systems are required to ensure that clients receive the high quality services that

they deserve (Myaya, 2004). Where services are currently integrated some HIV and

When the HIV and AIDS epidemic emerged in 1980s, family planning organizations

responded with some of the first HIV and AIDS prevention projects in the developing

world. Yet a review of the contributions of sexual and reproductive health services to

HIV and AIDS, conducted in 2003 for the World Health Organization found that

integrating HIV and AIDS services had not yet been implemented effectively except in a

few cases (Askew and Berer, 2003). Still it would be premature to conclude that

integration does not work. Much has been learnt, moreover from implementing various

strategies designed to achieve integration. Such strategies include diagnosis and treatment

of STIs, sexual risk reduction counseling, condom promotion and HIV voluntary

counseling and testing (Kathleen, 2004).

2.4.1 Integration of STI / HIV Prevention Messages into Family Planning.

Incorporating STIIHIV prevention messages in family planning services has been an

appealing strategy because family planning programs attract clients who often do not

access HIV programs services. Family planning staff can be trained to provide basic HIV

and AIDS prevention information and run an infrastructure of clinics and community

based programs for service delivery (Askew and Berer, 2003). However providing

STIIHIV prevention services through family planning programs is problematic because

these programs usually do not reach those at the greatest risk of HIV and AIDS infection,

including men, youth and single women (Lush et al., 1999). Even when married women

are among those at the highest risk of HIV and AIDS, they often do not have the powers

to protect themselves by either abstaining from sex insist on fidelity or condom use by

Family planning programs providers are often reluctant to offer HIV and AIDS services.

Many are concerned about the potential negative effects of HIV and AIDS

responsibilities and overall quality of services. Others fear occupational exposure to HIV

and AIDS or worry that providing the services will discredit family planning programs

(Maggwa and Ominde, 2003). Nevertheless providers have an obligation to their clients

to do what they can, wherever family planning services are offered, providers should be

equipped to counsel clients about STI's and HIV and AIDS and refer them for services

(Maggwa and Ominde, 2003).

2.4.2 Integration of Family Planning into HIV andAIDS Services.

Integration is also starting to move in the opposite direction. Pilot efforts have begun to

add family planning counseling and services to HIV services such as VCT and PMTCT.

VCT centers are emerging as primary targets for integration. Research from Africa and

the Caribbean shows that such integration is feasible and acceptable and large scale

integration efforts are being launched and expanded there (Strachan

et al.,

2004). Inresponse to research demonstrating the feasibility of integrating family planning into

VCT centers in Kenya, the government has moved quickly to develop and begin

implementing a strategy for family planning services at all VCT centers in the country.

Government leadership, an effective task force and stakeholder commitment have been

key to translating this important research into improved family planning and VCT

services for Kenyan clients.

The research conducted in June 2002 on the feasibility of integrating family planning into

VeT centers in Kenya suggested that it was feasible (Reynolds et al., 2003). The

feasibility research identified the opportunities, challenges for integration and to inform

the development of integration strategy. Overall, results suggested that counselor

training, referrals and contraception supply needs varied among centers. Researchers

concluded that decisions on whether to integrate services and to what extent to integrate

needed to be made at the facility level (Strachan et al., 2004).

Kenya was a promising site for integration even before the feasibility research was

conceptualized. The Ministry of Health had an ambitious program to expand veT

services. Nearly 300 VeT centers have been registered in the country and it is one of the

few countries to have developed national veT guidelines. The government also

recognized the benefits of family planning; with Kenya identified in a recent analysis as

one of six countries to mention family planning in its VeT guidelines (Strachan et al.,

2004). The VeT centers were funded through different mechanisms and because some

service providers thought they might be overburdened if family planning was introduced

into their facilities. To address these concerns the MOH established a subcommittee to

develop a strategy that could be applied to all facilities would not disrupt existing VeT

services and would not compromise the quality of either the family planning or the veT

services provided (Kenya Ministry of Health, 2004).

The subcommittee developed a strategy that identifies four levels of integration, each

and sexually transmitted infections, provision of information and counseling on

contraceptive methods that are not available at the veT centers are included in all levels.

Each progressive level requires more extensive training of VeT counselors and more

equipments and supplies. Thus the strategy recommends that VeT centers first focus on

achieving at least the first level of provision, while the fourth is viewed as a long term

goal (Kenya Ministry of Health, 2004). Tools for training current and new veT

counselors to provide family planning services have been developed and will be

combined to one comprehensive curriculum by Ministry of Health. The levels shown on

the table below differ however, in the methods that are provided on site (Kenya Ministry

of Health, 2004).

FHI is working with AMKENI and JHPIEGO to implement the first level of integration

as outlined in the strategy, into 20 proposed veT centers in two provinces in Kenya.

Operations Research will test the effectiveness, cost of implementation and lessons leamt

from this will inform activities to scale up integration throughout Kenya (Kenya Ministry

of Health, 2004).

Table 2.0 Adding Family Planning to VeT: Levels of Integration in Kenya

I

Level Services Provided

• Assessment of pregnancy and STI risks

• Information and counseling on methods

• Provision of condoms and pills

• Referral for other methods

Requiremen ts

• Minimal training of counselors to provide services • Availability of job aids,

condoms and pills

• Time and space to provide services

II • All services in level I • Provision of injectables

• All requirements in level I • Counselors trained to provide

injectables

• Adequate infection control procedures in place

• Additional equipment and supplies

III • All services provided in level II

• Provision of IDDS

• All requirements in level II • Counselors trained to provide

IUDS

• Additional equipment and supplies

IV • All services provided in level III

• Provision of full range of methods

• All requirements in level III • Medical doctor to perform

surgical procedures

• Additional equipments and supplies

Source: Kenya Ministry of Health. Strategy for the Integration of HIV Voluntary counseling and Testing Services and Family Planning Services. Nairobi, Kenya: National AIDS and STD Control Program and Division of Reproductive Health, 2004.

In 2006, in promoting an integrated approach to PMTCT in Sub-Saharan Africa, WHO

named Uganda a learning site where different ways of providing comprehensive PMTCT

services can be tested and evaluated (FBI, 2007). The integration was as a result of

findings of a research carried out in rural parts of the country by the US. Centre for

Disease Control and Prevention in Uganda. Nine out of 10 pregnancies among

HIV-positive women were unintended. These preliminary findings, based on 86 pregnancies

among 618 women in Tororo, Uganda, highlight the need to integrate the country's

family planning and HIV and AIDS services. Providing such services can help

HIV-positive women avoid unintended pregnancies and contribute to preventing PMTCT

(FHI, 2007).

The MOH of Uganda began integrating family planning, maternal and child health and

HIV and AIDS services in 2005. The technical support from WHO gives the Ministry an

opportunity to accelerate these efforts while strengthening the evidence base for

integration. A working group of reproductive health and HIV and AIDS expert has laid a

foundation for an integrated approach in Uganda. Its members incorporated information

about how to provide and evaluate HIV and AIDS services into family planning tools and

guidelines. They also developed training materials and service delivery guidelines, which

were used to train a central team of master trainers. Non-medical health workers will be

trained to provide certain community based services including HIV testing and

counseling (FBI, 2007).

This kind of integration aims at providing VCT and PMTCT clients, regardless of their

HIV status, the opportunity to avoid unintended pregnancies. For HIV infected women

ready access to family planning can help avert unintended pregnancies and thus reduce

the number of HIV infected infants. ART programs are also ideal sites for linking HIV

and AIDS and reproductive health services, such as gynecological care and screening for

gender-based violence. In Ghana, Engender Health and FHI are integrating family

planning interventions in ARV treatment and care programs (Perchal and Farrel, 2006).

Also being explored is the integration of family planning into care and support for

PLWHA. An FHI study was assessing integration of family planning promotion into the

services provided by volunteer care givers in a home-based care program for PLWHA in

South Africa and the results are yet to be published (USAID, 2003). Managers of a

similar program in Kenya ,the HIV and AIDS care support and prevention (COPHIA)

program carried out by US based Pathfinder International, decided that it was important

to train community healthy workers in family planning services and HIV prevention so

that they could respond to the reproductive health needs of clients and family members.

2.4.3 Integration of

mv

and AIDS Services outside Clinical SettingHIV and AIDS services or preventive health messages can also be integrated outside

clinical settings through interventions such as behavior change communication, peer

education, communication outreach, youth programs and social marketing (Shelton,

2004). For example in Nigeria's Lagos state, family planning counseling and referrals are

Communication Partnership, After training hot line counselors in family planning

counseling and referral in February 2004, HCP began promoting the new services

through radio advertisements, community rallies and USAID- sponsored family planning

programs (Shelton, 2004). In addition partners such as FBOs and CBOs can be crucial in

the integration of services. At the same time playa part in a successful referral systems.

Many CBOs represent the only accessible service point for integration at the community

levels and they need support in their efforts to deliver integrated services (Moloney et al,

2003). In Ethiopia, the main entry points of integrated services are the community-based

reproductive health agents who in their role in reproductive health services not only

promote family planning but also provide PLWHA's with HIV and AIDS and OVC'S

with home-based care kits, provide' referrals for HIV and AIDS services and spread

preventive messages (Kane and Colton, 2005).

Zimbabwe has followed suit and integrated family planning and HIV and AIDS services

at the community level. In primary health care clinics throughout the country, a single

health care provider is expected to offer not only basic services such as immunizations,

but also family planning services and information about HIV prevention. Some also

provide the antiretroviral drug neverapine for prevention of mother to child transmission

of HIV and AIDS (FHI, 2007). At other levels of the country's health system, however,

family planning and HIV and AIDS services are separate, vertical programs. Providers

countrywide are uncertain about how to advise HIV-positive women and couples about

family planning, which is a primary strategy for reducing HIV-infected births. Despite

services, family planning services have not been well integrated into PMTCT and remain

the program's weak link as such a change at the national level is required to strengthen

this link ( FHI, 2007).

The integration initiative began with an assessment of the family planning content of

national HIV and AIDS and reproductive health policies, guidelines and training

materials in June 2006. Eight of the 14 documents mentioned family planning, but none

provided guidance on how to integrate services. By October 2006, the assessment's

recommendations for strengthening or adding family planning content had been

incorporated into the national strategy on PMTCT and pediatric HIV and AIDS

prevention, care and treatment. Contraception for women and couples with HIVIAIDS, a training module developed by FHI and Engender Health, was adapted for inclusion in the

national PMTCT training curriculum to strengthen providers' ability to provide family

planning services (FHI, 2007). The module was also to train HIV and AIDS counselors

supported by a partnership project. These efforts and most other integration work in Zimbabwe have introduced family planning into HIV/AIDS services. Recently, however,

the Zimbabwe National Family Planning Council (ZNFPC) together with partnership

project trained family planning counselors to provide HIV and AIDS services. The

training covered; family planning and other 'positive living' issues such as diet, exercise,

medical care and psychological and social support.

The Ministry of Health and Child Welfare of Zimbabwe in conjunction with partnership

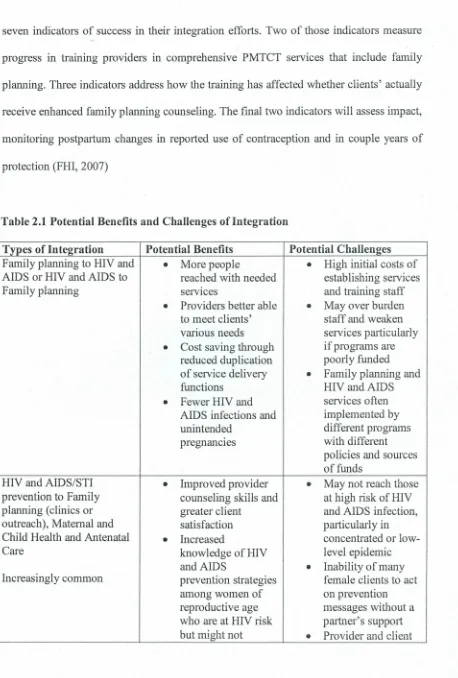

seven indicators of success in their integration efforts. Two of those indicators measure

progress in training providers in comprehensive PMTCT services that include family

planning. Three indicators address how the training has affected whether clients' actually

receive enhanced family planning counseling. The final two indicators will assess impact,

monitoring postpartum changes in reported use of contraception and in couple years of

protection (FHI, 2007)

Table 2.1 Potential Benefits and Challenges ofIntegration

Types of Integration Potential Benefits Potential Challenges

Family planning to HIV and

•

More people•

High initial costs ofAIDS or HIV and AIDS to reached with needed establishing services

Family planning services and training staff

•

Providers better able•

May over burdento meet clients' staff and weaken

various needs services particularly

•

Cost saving through ifprograms arereduced duplication poorly funded

of service delivery

•

Family planning andfunctions HIVandAIDS

•

Fewer HIV and services oftenAIDS infections and implemented by

unintended different programs

pregnancies with different

policies and sources of funds

HIV and AIDS/STI

•

Improved provider•

May not reach thoseprevention to Family counseling skills and at high risk of HIV

planning (clinics or greater client and AIDS infection,

outreach), Maternal and satisfaction particularly in

Child Health and Antenatal

•

Increased concentrated orlow-Care knowledge of HIV level epidemic

and AIDS

•

Inability of manyIncreasingly common prevention strategies female clients to act

among women of on prevention

reproductive age messages without a

who are at HIV risk partner's support

otherwise receive bias against

-HIVandAIDS condoms

information and

•

Difficult for manycounseling Family planning

•

Many HIV-infected programs to assume births averted by new tasks due to preventing HIV reduced funding and infection among weak systemswomen of

•

Need to train reproductive age providers to talkabout sexual behavior and relationships VCT to Family planning or

•

Increased access to•

May not be cost-Antenatal care and use ofVCT effective if mostservices clients are not at risk

Limited but increasing

•

Reduce stigma of HIV and AIDSassociated with HIV

•

Possible provider and AIDS reluctant to offer•

Increased awareness HIVandAIDSof healthy sexual services due to behavior stigma associated

•

More targeted with HIV and AIDS family planning and fears ofcounseling based on occupational

HIV serostatus exposure to the virus

•

Many HIV-infected•

For VCT, special births averted by skills and equipment identifying infected plus strong systemswomen, then for supervision, helping those who monitoring, logistics are not pregnant management and

avoid unintended referrals for follow-pregnancies or up care needed refening those who

are pregnant for antiretroviral drug therapy

Family planning to VCT or

•

Expanded access to•

For family planning,Antenatal Care ( usual site famil y planning for special provider

of PMTCT services) all VCT clients, skills, equipment,

Limited, but increasing youth aswell as strong

•

Increased systems forknowledge of dual supervision,

protection strategies monitoring logistics to prevent both management and unintended referrals for follo w-pregnancies and up care needed HIV and AIDS 8 Unique

"infection contraception

•

Greater opportunity consideration for for clients, HIV infected regardless ofHIV women serostatus to avoidinitial or subsequent unintended

pregnancy

•

Can greatlycontribute to averting HIV-infected births among HIV -infected women

STI care to Family

•

Reduced risk of HIV•

Misdiagnosis moreplanning, Maternal and and AIDS infections likely since family Child Health or Antenatal through STI planning clients may

Care prevention, not be at high STI detection and risk

Emphasis decreasing treatment

•

Current lack of•

Fewer cases of simple, effectivesecondary infertility, technologies to pelvic inflammatory diagnose and treat disease and negative STI's in

pregnancy outcome asymptomatic arising from women orwomen untreated with vaginal reproductive tract discharge

infections/STI's in

•

When diagnosis iswomen uncertain, partner notification not

feasible; women treated

syndromically at

risk ofreinfection

Regardless of when, where and how family planning and HIV and AIDS services are

integrated, family planning remains one of the most effective ways to enhance the we

ll-being of women and their families. By enabling women to avoid unintended pregnancies

and by reducing the risks associated with age at pregnancy, too many pregnancies, or

pregnancies spaced too closely together, family planning prevents about 2.7 million

infants deaths and 215 000 pregnancy-related deaths in the developing world each year

These benefits of family planning may be particularly important for HIV-infected

women, whose health is already compromised and for their children (Singh et al, 2003).

2

.

5 Factors to consider when Integrating HIV and AIDS and Rep

r

oducti

v

e

H

ealth

Serv

i

ces

According to the new technical guidelines from the US Agency for International

Development (USAID), integration is most appropriate in countries where the epidemic

is generalized. In these countries the number of people who need reproductive health

services and HIV and AIDS services are likely to be high (USAID, 2003). Family

planning and HIV and AIDS services needs intersect in a growing number of countries.

In 2000,55 countries had generalized epidemics up from 25 countries in 1990 (Walker et

al, 2001). In contrast in countries where the epidemic is low level or concentrated among

people at highest risk of infection, HIV and AIDS services specifically targeting those

individuals are needed. Integrating services in such settings is unlikely to be cost

-effective (USAID, 2003). Even in countries where HIV and AIDS primarily affect high

risk groups, good opportunities may exist to reach people in need HIV and AIDS or

family planning services through service integration.

Table 2.3 Appropriate Service by Type ofHIV/AIDS Epidemic

HIVIAIDS Epidemic Type Service for Type of Population

Generalized: HIV prevalence above 1% Integrated family planning and HIV and

among pregnant women. AIDS services for general population and

high-risk population.

Concentrated: HIV prevalence above 5% Family planning for general population

in at least one at risk sub population but HIV and AIDS services and possibly

below 1% among pregnant women. family planning for high-risk population.

Low level: HIV and AIDS prevalence Family planning for general population

below 5% in at risk sub-populations and HIV and AIDS services for high-risk

below I% among pregnant women population

Table 2.3 shows the appropriate service by type of HIV and AIDS epidemic adapted from

USAID. Family planning and HIV integration: Technical Guidance for USAID-suppOlted

field program.

Some reproductive health services for instance may tailor their services to reach those at

highest risks such as the youth, men and commercial sexs workers (Kathleen, 2004).

Before attempting to integrate services, program managers need to be aware of the

potential benefits and challenges confronting them and consider whether integration

make sense. The likely hood that combining the two services will be cost effective

depends on clients' need, the prevalence of HIV and AIDS in the area and the strength of

integration depends on a program's capacity, the costs and resources available to support

CHAPTER THREE

MATERIALS AND METHODS

3.1 Research Design

A longitudinal study design was employed. Records of clients utilizing the eight

study sites were reviewed. Retrospectively and prospectively for six months from the reproductive health services namely family planning, antenatal, postnatal, well-baby,

well-woman, Postabortal, management of STIs, and management of infertility from the

onset of integration. The results of the retrospective review generated the baseline data.

While the prospective review generated results that would be compared against the

'I

1 . I I

I

baseline data to assess whether the integration had affected the utilization of the

respective reproductive health services. In addition to how the integration had affected

the utilization of the respective reproductive health services. To build on the data

generated from the review of records, primary data was collected from clients seeking

reproductive health services from the study sites and to service providers working in the

same sites.

3.2 Definition and Measurement of Study Variables

The independent variable was HIV and AIDS Care that was integrated into reproductive

health services. The utilization of reproductive health services was the dependent

variable. The study used several variables within the independent variable to assess the

effects of integration on the utilization of reproductive health services. The variables

were changes in uptake of services, acceptance levels of integrated services, changes in

quality of services and awareness.

3.2.1 Changes in Uptake of Services

Uptake of services refers to the utilization of HIV and AIDS Care and reproductive health

services. It is synonymous to sought and access. The changes were measured through the

comparison of the total number of clients who utilized services before and after

integration in general. Also comparisons were drawn between the total number of clients

utilizing services from Nairobi-West and Thika Family Care Medical clinics before and

after integration. Further, comparisons were drawn between the number of clients who

utilized the respective reproductive health services in general and from Nairobi-West and

Thika Family Care Medical clinic before and after integration. The data that was used for

comparison purposes was generated through the review of monthly medical records

prospectively and retrospectively for six months after integration.

3.2.2 Acceptance of Integration

Acceptance is the willingness to adopt and utilize the services that had been integrated.

Information to assist the study to measure the acceptance of integration was collected

through questionnaires. The study population responded to questions on awareness of the

implementation of integration, their preference based the pro and cons of integrated

3.2.3 Changes in Quality of Services

Quality is the goodness of services. Rating of goodness of services as very poor, poor,

fair, good and very good was used to capture the views of clients. To measure changes in

quality, clients utilizing the services drew comparisons on four parameters of qualities of

services before and after integration. The four parameters were; waiting time before

being attended to, efficiency and number of service providers, availability of services

sought for and accuracy of information relayed to clients. Clients responded to questions

related to these parameters.

3.2.4 Awareness

Awareness is being well informed on the implementation of integration and the HIV and

AIDS services that were integrated. The awareness was measured through the study

population responding to questions on how they got informed about the integration and

the availability of HIV and AIDS care services.

3.3 Location of the Study

The study was conducted in Nairobi-West and Thika Family Care Medical clinic in

Nairobi city and Thika town respectively. The two clinics are part of the four Family

Care Medical Clinics currently integrating HIV and AIDS care into reproductive health

clinics managed by F.H.O.K.

33.1 Description of Thika Town

Thika town is a market town in Central Province, Kenya lying on the A2 road 40 km

north east of Nairobi city and on the Thika river. According to 1999 census results, the

town has a population of 88,265 people. It is externally serviced by a dual carriage way to

Nairobi city, a high way to Garissa and also a railway line. Economic activities of the

town include agriculture, food processing, tannery, textile and motor vehicle assemblies.

The Thika Family Care Medical clinic is located opposite the main bus terminus along

workshop road in the town.

3.3.2 Description of Nairobi City

Nairobi is the capital and largest city in Kenya. It is the most populous city in East Africa

with an estimated population of 3 million. It is currently the 13th largest city in Africa, In

addition, it is one of the most prominent cities in Africa politically and financially. It is

home to many companies and organizations. More over it is an established hub for

business and culture. Nairobi enjoys full administrative province and is the smallest

province in size and entirely urban. Nairobi - West Family Care Medical clinic is located along Mai -Mahiu road off Langata / Mbagathi road junction in Kibera division.

3.4 Target Population

Service providers working in integrated set-ups and clients seeking services in the same

3.5 Study Population

The study population consisted of;

• Reproductive health services offered in Nairobi-West and Thika Family clinic.

The reproductive health services of interest to the study were; antenatal, postnatal,

management of STls, postabortal care, family planning, well-woman, well-baby,

and management of infertility.

• Clients seeking reproductive health services from the two clinics. The clients were

women of the reproductive age bracket which is 15 to 49 years of age.

• Service providers working in the study areas.

3.5.1 Criteria for Inclusion

1. Clients seeking reproductive health services at the specific time of the study and

were willing to participate.

11. Service providers who were on duty at the specific time of the study in the clinics

and were willing to participate.

3.5.2 Criteria for Exclusion

1. Clients seeking reproductive health services at the specific time of the study and

were not willing to participate

11. Service providers who were on duty at specific time of the study and were not

willing to participate.

3.6 Sampling Techniques and Sample Size

3.6.1 Sampling Techniques

Nairobi-West and Thika Family Care Clinics were conveniently sampled due to their proximity to the research team. A census of all reproductive health services offered in the

study was conducted. In addition a key informant interview was canied out where all the

service providers working in the two facilities were eligible. Availability sampling was

used to select the clients who participated in the study. This involved the sampling of

clients readily available and willing to participate in the study till desired sample size was

arrived at. The study employed the availability method of sampling because the

population of interest to the study was out patient. This meant that the members of the population visited and left the clinics at their own convenient time without being

admitted into the wards.

3.6.2 Sample Size Determination for Clients

The sample size was arrived at by calculating using the standard formula as used by

Fisher et al., (1998).

Where,

N

=

Sample sizeZ= standard normal deviate (1.96) which corresponds to 95% confidence interval

q

=

1-p=

0.5d = Degree of accuracy = 0.05

D = Design effect = 1

= Thus n = 1.962 x 0.5 x 0.5 x 1

=

384The above formula is only applicable for a population that is more than 10,000. Therefore

after calculation of sample size with the above formulae, the formulae below was used

since the average monthly population of clients seeking reproductive health services in

the two clinics was 391 which was less than 10,000

nf = n

l+n

N

Where,

nf = sample size of a population less than 10,000

n = sample size arrived at using the formula as it was used by Fishers et al., (1998), for a

population greater than 10,000

n ~ the population of clients seeking reproductive health services i.e. 391: (~

nf= n

l+n

N

nf= 384 1+384

391

=

194 womenProbability proportion to sample size as shown below was used to determine the number

of clients to be interviewed in the two clinics as shown below.

Nairobi West

=

140 x 194391

69 women

Thika =251 x 194 = 125 women

391

3.7 Construction of Research Instruments

Interview schedules and self-administered questionnaires were used to collect clients'

perception towards integration. The instruments contained both open and close-ended

questions. Further the instruments were subdivided into three sections; demographic,

reproductive health services and integrated services. This was to aid in capturing the

clients' perception of integrated services. In addition a key informant interview schedule

was constructed to collect the views of service providers regarding integration.

3.8 Pilot Study

Pilot study was carried out at Phoenix Family Care Clinic along Kenyatta Avenue in

self-administered questionnaires were used to collect clients' perception on integration.

Availability sampling was used to select the clients. Key informant interviews were also

carried out to collect the service providers' views regarding integration. After the pilot

study a mini analysis was carried out to determine whether the instruments yielded the

required data. Based on the results of the mini analysis the instruments were revised

accordingly.

3.8.1 Validity

Research assistants were trained on the contents of the interview schedule and on how to

carry out an interview. The research instruments were pre-tested in the selected pilot

center.

3.8.2 Reliability

The research instruments were pre-tested in the selected pilot center. A mini analysis was done the data collected. After which the instruments were reviewed accordingly.

3.9 Data Collection

Primary and secondary data were used. Interview schedules and self-administered

questionnaires were used to collect the views of the clients regarding integration. The two

research instruments were administered to each and every client who was available and

willing to participate in the study at the time the research was happening till the desired

sample size of 194 was achieved. The literate clients filled in the self-administered

schedules with the help of a researcher. Key informant interview schedules were used to

collect service providers' views regarding integration. The information collected through

the key informant interview was used to build on the data collected through the

questionnaires and interview schedules. Records of reproductive health services utilized

by clients were reviewed retrospectively and prospectively. The review entailed

extracting the number of clients who utilized the respective reproductive health services

from the medical reports generated on a monthly basis in the study sites. Retrospective

study covered six months preceding integration while the prospective study was done for

six months from the onset of the integration.

3.10 Data Analysis

Statistical analysis was done using SPSS software. Data was edited, coded and entered.

Descriptive analysis was done to determine frequencies, percentages and means.

ANOVA was used to test whether there was a significant difference in the utilization of

reproductive services before and after integration. Chi-square was used to test clients'

perceptions and the views of service providers regarding the integration of the services.

Data was presented in graphs, pie-charts and tables.

3.11 Logistical and Ethical Considerations

Permission to carry out the study was sought from the Ethical Committee of Ministry of