U$A U$A U$A U$A

U$A U$A U$A U$A

U$A U$A U$A U$A

U$A U$A U$A U$A

U$A U$A U$A U$A

U$A U$A U$A U$A

U$A U$A U$A U$A

U$A U$A U$A U$A

U$A U$A U$A U$A

U$A U$A U$A U$A

U$A U$A U$A U$A

U$A U$A U$A U$A

U$A U$A U$A U$A

Understanding and

Managing Receivables on

U.S.Government

Contracts

Although timely cash collection has significance for all firms, it’s particularly important for firms con-tracting with the U.S. government. Our primary objective here is to provide insights into actual billing and collection cycles so firms contracting with the government can plan and improve their billing and collection processes. We’ll cover the peculiarities of government contracting, the types of government contracts, the billing and collection processes, and some suggestions for process improvements.

UN I Q U E CH A L L E N G E S

Complicated contracts and extensive oversight and documentation contribute to the relatively large receivables. The highly regulated nature of govern-ment contracting requires more extensive documen-tation for billing and collecting purposes than does commercial contracting. Government contracting

also covers a wide range of products and production stages, with individual contracts tending to be uniquely tailored to the government’s needs. Conse-quently, billing and collecting requires stricter atten-tion to contract details. Together, the contract details and documentation requirements significantly add to the cost and time required to collect on govern-ment contracts. Furthermore, governgovern-ment contract-ing has unique terminology such as not currently billable, milestones, withholds, and subject to future settlement.

In addition, the government requires extensive oversight of its payments to contractors and has developed detailed requirements in the Federal Acquisition Regulations (FAR). Also, multiple gov-ernment agencies can be involved in the payment process, and because they may have incompatible EDP systems, manual coordination of documents and/or duplicate invoice documents are required.

IT IS COMMON FOR GOVERNMENT CONTRACTORS to have large

receivables. In terms of 1999 government sales, the nine largest government

contractors report average accounts receivable balances of approximately 23% of

total sales. These government receivables are substantially larger than

receiv-ables on commercial sales. Case in point: Boeing’s government receivreceiv-ables at

year-end 1999 were $2 billion on sales of $19 billion (10.5%), while Boeing’s

commercial receivables were only $1.5 billion on sales of $38 billion (3.9%).

That’s 25% more government receivables on half the sales. The challenge:

TY P E S O F GO V E R N M E N T CO N T R A C T S Contract terms largely determine a government con-tractor’s ability to invoice and relate directly to the uncertainty of future costs. Figure 1 illustrates the relationship of product production stage, cost uncer-tainty, and contract type. The contracts, which spec-ify billable events as well as when and how

payments will be made, fall into two categories: cost-plus and fixed-price.

Government Contract Types

CPFF Cost-Plus Fixed Fee

CPAF Cost-Plus Award Fee

CPIF Cost-Plus Incentive Fee

FPI Fixed-Price Incentive

FFP Firm Fixed Price

From a contractor’s perspective, contract type is related directly to the level of uncertainty or risk in estimating future costs. This, in turn, is related directly to a product’s stage of development (i.e., from research and development [R&D] to full-scale production). R&D programs tend to be cost con-tracts because future costs cannot be easily deter-mined, while well-established programs with predictable production schedules tend to be fixed-price contracts. Here’s a closer look at each approach.

CO S T- PL U S CO N T R A C T S

Cost-plus contracts have three common variations: Cost-Plus Fixed Fee (CPFF), Cost-Plus Award Fee (CPAF), and Cost-Plus Incentive Fee (CPIF). The basic cost contract, the CPFF, reimburses the con-tractor for incurred costs and adds a fixed amount as profit. The CPAF contract rewards contractors for product performance or early completion, and the CPIF contract rewards contractors for reducing costs by adding a percentage of the cost savings to the contractor’s profit or fee. Invoicing on cost-plus con-tracts can occur as costs are incurred although full compensation is unlikely until the contract is com-plete and final overhead billing rates are settled.

Cost contracts also have an additional profit com-ponent: cost of money (COM). This billable amount is calculated using an estimate of capital employed (plant and equipment plus assets under construc-tion) multiplied by an interest rate provided by the Secretary of the Treasury. In effect, the contractor is provided a return on its investment in property, plant, and equipment.

Government cost contracts have at least two added peculiarities: Forward Rates and Billing Rates. Cost-plus contracts are designed to allow con-tractors to bill all incurred costs that are related to the contract plus a profit. Incurred costs can be sum-marized broadly as direct (material and labor) and indirect (manufacturing, engineering, and material overhead). Assigning direct costs to programs is straightforward, but overhead is allocated to pro-grams based on a pre-established application rate known as the forward rate, calculated as follows:

Forward Rate =

Estimated Overhead + Estimated Activity Base

Although contractors use forward rates for finan-cial accounting purposes, forward rates are not always used for billing purposes. Rather, the govern-ment provides billing rates that are, in most cases, less than forward rates. Thus some overhead costs cannot be billed until the contract is closed, which means such unbilled costs can remain in inventory a very long time, even up to five years. In addition, contracts cannot be completely settled until the gov-ernment establishes final billing rates for each year of the contract. These receivables are often referred to as “subject to future settlement” in annual reports.

Cost-plus contracts can be billed as often as the Federal Acquisition Regulations allow, but contractors typically bill cost-plus contracts twice monthly. The

Production Stage

Research Prototypes Manufacturing Ongoing

Development Development Production

Uncertainty

More Less

Contract Type

Cost Fixed Price

CPFF CPAF CPIF FPI FFP

Figure 1:

The Relationship of Production

profit portion of a billing is determined using the con-tract’s profit booking rate, calculated as follows:

Profit Booking Rate = Estimated Profit + Estimated Costs

For financial accounting purposes, profit booking rates should always be calculated based on the total expected costs and negotiated profit (i.e., the final contract value). The final profit booking rate, how-ever, may be affected by funding, supplemental agreements, other negotiated changes to the initial contract, and contractor performance. Thus the prof-it booking rate can change wprof-ith contract revisions. FAR also provides for a 15% withhold on fee billings up to a $100,000 limit per contract, which is com-monly released at contract completion or closeout. The result: The profit amount recorded likely will differ from the profit amount billed and, therefore, an “unbilled” fee will be accrued and remain uncol-lectible until the contract is closed. Depending on the program and type of contract, unbilled fees can remain uncollectible for a long time.

FI X E D- PR I C E CO N T R A C T S

Fixed-price contracts have two common variations: Firm Fixed Price (FFP) and Fixed-Price Incentive (FPI). An FFP contract does not change unless both parties renegotiate the price. The final price of an FPI contract depends on cost performance and an incentive-sharing ratio. Invoicing on fixed-price con-tracts occurs after product delivery or after

inspec-tion and acceptance by a government quality assur-ance representative (QAR) at the contractor’s plant. Yet most long-term fixed-price contracts allow con-tract financing in the form of either progress- or per-formance-based payments.

Progress payments are based on incurred produc-tion costs, while performance-based payments allow billing to occur upon satisfactory completion of con-tractually defined objectives. In essence, both progress- and performance-based payments provide financing over the life of long-term fixed-price con-tracts. Neither represents “earned” receivables in that delivery has not occurred and a sale is not recognized. Therefore, both progress- and performance-based payments are recognized in the financial statements by reducing costs accumulated in inventory.

In some cases there is a long lapse of time between when costs are incurred and when a deliv-ery is made. If the contractor meets certain mile-stones prior to a contractually defined billing date, the contractor will accrue a partial sale and a receiv-able; however, billing can occur only on the contrac-tually defined billing date. These receivables are sometimes referred to as “amounts not currently billable” in annual reports.

No matter what contract type is used, contract vari-ations will sometimes overlap production stages. Both CPIF and FPI contracts, for instance, can be used for R&D programs. Also, contracts may combine contract types such as a cost contract having both an award fee component and an incentive component.

Billing Events Billing ProcessContractor’s Payment ProcessGovernment’s Cash Received

In Audit

Work-in-Process

Subcontract Work

Billing Rates

Interim/Final

Withholds

Returns

BI L L I N G A N D CO L L E C T I O N CY C L E S

To effectively deal with and anticipate the peculiari-ties of the government payment system, many con-tractors develop specific billing and collection processes. Figure 2 presents an overview of a typical billing cycle and the government’s typical payment cycle. The billing process requires up to three inputs:

1. Evidence of a billable event,

2. Costs accumulated from work-in-process includ-ing subcontractors, and,

3. Either interim or final billing rates from the

government.

Once invoiced, requests for payment have four possible outcomes:

1. The invoice is paid in full,

2.The invoice is returned because of either con-tractor or government error,

3.A portion of the invoice is denied until further performance by the contractor (a withhold), or

4.The invoice is placed in government audit. So you can better understand and control the billing and collection cycle, the process can be divid-ed into its four major components: internal process-Billable Costs

Accumulated

Accounts Receivable

Contractor Bank Account

Internal Float 1– 4 Days

Administrative Contracting Officer (ACO)

~

~

~

~

~

~

Preparation 0–1 Days

Approval 0 –3 Days

Electronic Document Transfer

Electronic Funds Transfer

~

~

Payment Processing 7– 20 Days

Defense Finance and Accounting Service (DFAS) Figure 4:

The Billing and Collection Cycle for Fixed-Price Progress

and Performance-Based Payments

Billable Costs Accumulated

Accounts Receivable

Contractor Bank Account

Internal Float 1– 4 Days

Defense Finance and Accounting Service (DFAS)

~

~

~

~

~

~

Preparation 0–1 Days

Payment Processing 14–20 Days

Electronic Document Transfer

Electronic Funds Transfer

ing, invoice preparation, invoice approval, and pay-ment. Internal processing and invoice preparation are the contractor’s responsibility, while invoice approval and payment are the government’s responsibility.

The Contractor Billing Process

Because individual contracts are unique and govern-ment regulations are strictly enforced, contractors should assign an accounts receivable specialist to actively oversee each contract and prepare invoices. Although billing events differ by contract, once a specialist is notified of a billing event, the billing process can be standardized easily.

Billing Cost-Plus Contracts.Cost-type contracts usually have the timeliest collection because cost contracts can be invoiced every two weeks begin-ning on any week of the month, and the govern-ment now allows invoices that have been

pre-approved to be submitted electronically. Figure 3 illustrates a billing and collection cycle for cost-plus contracts.

Recall that incurring costs is the billable event for cost-plus contracts. Billed receivables include billed costs, fees, and cost of money. The billing process begins with the accumulation of costs by the con-tractor’s EDP system, which collects program costs by contract identifier. Costs then are accumulated and burdened with overhead over any period, partic-ularly at low EDP usage times such as weekends and evenings.

By definition, a contractor’s internal processing time represents the difference between an artificial accounting cutoff date for accumulating costs and an invoicing date. The timing of the accumulations and the scheduling of the billing process can add days to internal processing time. Weekend data processing, for example, can add up to a week to internal processing if the cutoff date is Friday and the billing date is the following Friday. Yet three to four days is a reasonable estimate for internal processing.

Even so, an accounts receivable specialist usually will receive a cost-type invoice from the EDP sys-tem on a specific day each week. An invoicing schedule like this helps to spread cash inflows more evenly than if billings are batched.

Invoice processing for military contracts primarily occurs at the Defense Finance and Accounting Ser-vice Center located in Columbus, Ohio (DFAS Columbus). DFAS Columbus electronically transfers the payments to the contractor. Both industry and

the government encourage electronic transfer of invoices and payments, which has reduced collec-tion cycle time by four to seven days.

A typical process cycle time for cost contracts is as follows.

Cycle Time in Days Best Likely

Internal Processing 1 4 days

Preparation 0 1 day

Approval - (Direct Submission)

Payment 14 21 days

Total Cycle 15 26 days

Billing Fixed-Price Contracts.Figure 4 illustrates the billing process for fixed-price contracts that can have two billing events: progress- and performance-based payments (financing) and delivery invoices (actual delivered items). Progress- and performance-based payment requests typically are invoiced every four weeks beginning on any week of a month.

Progress payments essentially are financing arrangements based on incurred production costs. It follows that the billing and payment cycle for these payments is similar to the billing and payment cycle for cost-plus contracts, where the contractor can periodically accumulate costs, including subcontrac-tor costs, and prepare progress payment requests. Internal float again represents the difference between an accounting cutoff date for accumulating costs and an invoicing date.

If a contractor has been approved for direct sub-mission, progress payment requests (except for the first request) are sent directly to the payment office. Other payment requests must be approved by an administrative contracting officer (ACO) before they are submitted to the payment office. An ACO, typically located at the contractor’s manufacturing site, has administrative responsibility for the con-tract and can take several days to approve it, depending on its complexity. An ACO usually approves the request electronically in a system linked to DFAS Columbus. A typical process cycle time for progress- and performance-based payments is as follows:

Cycle Time in Days Best Likely

Internal Processing 1 4 days

Preparation 0 1 day

Approval 0 3 days

Payment 7 20 days

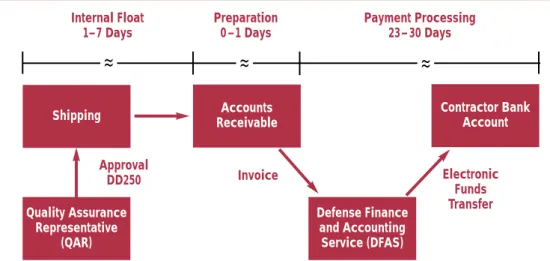

Figure 5 illustrates the billing process for fixed-price contract delivery events. The process begins when a government quality assurance representative approves an item shipment. A QAR is usually locat-ed on the contractor’s manufacturing site and has responsibility for approving product deliveries. In most cases, a QAR manually or electronically signs a delivery document known as a DD250 or a Certifi-cate of Completion. However, if a contractor has been approved for direct submission, progress pay-ment requests are sent directly to the paypay-ment office for immediate approval.

Signing the delivery document represents the government’s acceptance of the product and the beginning of the billing cycle. The document moves to an accounts receivable specialist, who then pre-pares an invoice that is sent to DFAS. Internal pro-cessing time, representing the difference between the delivery document signoff date and the date the document is received by the billing department, ranges from one to seven days. A typical process cycle time for deliveries is as follows.

Cycle Time in Days Best Likely

Internal Processing 1 7 days

Preparation 0 1 day

Approval 0 0 days

Payment 23 30 days

Total Cycle 24 38 days

Billing Constraints

Two additional factors affect interim or final billing: subcontractors and overhead billing. Both factors

require inputs external to the contractor. It is a contractor’s responsibility to invoice the government for work provided by subcontractors. For progress payment requests and cost vouchers, the ability to invoice for subcontractor work depends on whether or not the subcontractor has billed the prime contractor.

For deliveries, the ability to invoice for subcon-tractor work depends on receipt of documentation (i.e., a DD250) from the subcontractor that can then be submitted to the government. Billings are occa-sionally delayed because a subcontractor has not provided a delivery document. This can occur even though the contractor has paid the subcontractor and the item has been delivered to the government. Efforts are under way to allow subcontractors to electronically update contractor and government records when subcontractor deliveries are made to the government. To substantially improve the billing and collection cycle, the government will need to allow the deliveries themselves to serve as the critical event for payment rather than the sub-contractor DD250.

Overhead billing presents another constraint. The government authorizes interim overhead billing rates that are used to determine billable overhead. In many cases, billing rates are less than the forward rates, which creates a portion of overhead that is unbillable. The unbilled overhead is not billed until the billing rates are revised by the government or overhead is settled. After contracts are physically complete, unbilled overhead costs remain in inven-tory until the government establishes a quick close

Shipping ReceivableAccounts Contractor BankAccount

Internal Float 1–7 Days

Defense Finance and Accounting

Service (DFAS)

~

~

~

~

~

~

Preparation 0 –1 Days

Payment Processing 23– 30 Days

Invoice Electronic Funds Transfer

Quality Assurance Representative

(QAR)

Approval DD250

or final rates for all the years where contract work occurred.

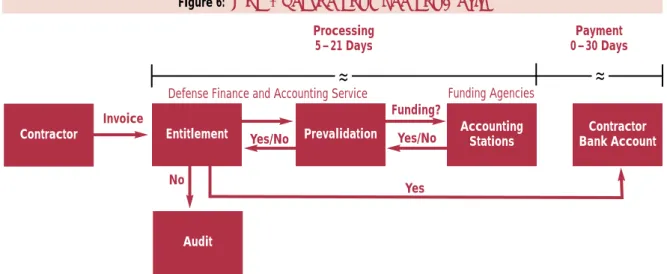

TH E GO V E R N M E N T PAY M E N T PR O C E S S Like the contractors, the government has different processes for cost-plus and fixed-price contracts, but both contract types follow similar processes after the government receives an invoice, which is illustrated in Figure 6. Invoice processing at DFAS begins in Entitlement. Entitlement verifies the contract as well as the contract’s total funding, then forwards the request to Prevalidation to verify that funds are available from the agencies funding the contract.

To verify funding, Prevalidation contacts the funding agencies’ accounting stations, which usually are not located at DFAS Columbus. More than one agency can be responsible for funding, and funding can come from different congressional appropria-tions. Funding agencies can include the military ser-vices (e.g., the Air Force, Army, Navy, and Marines); strategic alliances (e.g., the North American Treaty Organization [NATO]; or other public agencies (e.g., the Coast Guard or the North American Space Administration [NASA]). The Joint Strike Fighter (JSF), designed to meet many military objectives, is an example of a program funded through a variety of agencies.

When the accounting stations have verified fund-ing, Prevalidation returns the invoice to Entitle-ment, which then authorizes payment. Once authorized, the payment, typically an electronic bank transfer, can be delayed by law for 30 days (delivery payments only). The Entitlement and Pre-validation processes, including the Pre-validation by

accounting stations, can take as little as five days or as long as several weeks to complete.

Payment Delays

Sometimes the accounting stations do not verify funding because of government or contractor error or because funding has expired. DFAS Columbus then attempts to reconcile discrepancies among the invoice, the contract, and the funding sources. Rec-onciliation can add weeks to processing time, and if funding cannot be reconciled, the invoice will often fall into Audit, which often means a six-month or longer payment delay.

Other factors also contribute to delays in pay-ment. Invoices can be returned for additional data or corrections, and, although making corrections requires little processing time, resubmitted invoices enter the government system as new invoices, restarting the entire payment process.

Withholds delay payment as well and occur when the government considers a delivery to be deficient. Withholds are settled when the remaining parts are shipped or the performance issue is resolved, but billing for previously invoiced withholds typically requires a new billable event and will begin as a new entry in the billing cycle.

Expired funding may also cause great delay in payments. Depending on the type of appropriation, the government funding authority lasts only six to eight years, after which the funding expires. Fund-ing can also expire when fundFund-ing for a particular contract has been fully allocated. Sometimes an accounting station will report that funding has expired when it has not. This occurs when the

Contractor Entitlement Prevalidation Bank AccountContractor

~

~

Processing 5 – 21 Days

No

Yes

~

~

Payment 0 – 30 Days

Accounting Stations

Invoice

Yes/No

Funding?

Yes/No

Audit

Figure 6:

The Government Payment Cycle

accounting station has misallocated the funding on an earlier invoice. As mentioned earlier, DFAS Columbus and accounting station records do not always reconcile, and resolving the issues can delay invoice payment for years.

TH E CR I T I C A L RO L E O F T H E CO N T R A C T The contract plays a critical role in any business but particularly so with the government. Nothing can be assumed when contracting with the government. Contracts must define the products, delivery processes, billing events, and payment processes. These contracts are complex. They can be greatly complicated by the proliferation of negotiated changes, so initial contracts that explicitly consider future modifications facilitate collections. Contracts also are unduly complicated when multiple govern-ment agencies or service branches fund a contract. The need to reconcile funding across agencies and appropriations needlessly complicates the govern-ment’s payment procedures and makes errors more likely.

It follows that billing and collection cycles should be explicitly considered when contract documents are prepared. Today some contractors are writing model contracts that greatly facilitate timely pay-ments. The model contracts explicitly consider the contract language, the preparation of billings, the likelihood of future contract changes, and the sources of funding. The model contracts also emphasize standard contract language.

The ability of nonlegal government and contractor personnel to understand contract terms is a critical factor in the preparation of collectible billings. At the same time, detailed specification of billing events reduces the likelihood of billing conflicts as well.

TH E FU T U R E

The government requires extensive oversight and duplication in its defense procurement system. This oversight has led to regulations requiring multiple approvals and record keeping across different gov-ernment agencies. Some oversight is being eliminat-ed by the government’s acceptance of Best

Commercial Practices, which involves certifying a manufacturing process and, therefore, eliminating the inspection and approval of individual products. The result: All outputs from the manufacturing process are automatically acceptable for payment.

Duplication is another challenge. Contracts may require the contractor and different government

agencies to keep records—often manually. In the past, contractors could not assume the government would keep accurate records nor that the govern-ment could coordinate data between its agencies. Therefore, some contractor processes were designed to duplicate already duplicated government process-es. As the government and contractors improve and coordinate their EDP systems, many of the duplica-tions are being eliminated. Furthermore, EDP sys-tems are eliminating manual data entries, which, in turn, are reducing the majority of invoicing errors.

The government is aware that the processes that evolved to ensure oversight and duplication are eco-nomically inefficient. The government is requesting solutions from the private sector, but funding limits the government’s ability to reform its systems as cur-rent government computing systems become obso-lete. Furthermore, funding that occurs is spread across many different agencies, which may not coor-dinate their computing systems.

For these reasons, an opportunity exists for con-tractors to assume some activities currently managed by the government. For example, current commer-cial practice places a customer-supplier interface onto the Internet, providing websites with secure portals into a common database so all parties to a contract can retrieve or add data from a site. In such an environment, contract changes can be coordinat-ed more easily between government agencies and between contractors and the government. Further-more, firewalls can be put in place to protect sensi-tive information.

In summary, the government payment process is very detailed and highly complex. Opportunities for error at any step in the process can create delays or very late payments, but joint government and con-tractor efforts to streamline the process will ulti-mately benefit both parties. Competitive advantages will accrue to the defense contractors that can sus-tain efficient collection processes, and taxpayers will ultimately accrue the benefits of more efficient

gov-ernment processes. ■

Roger C. Graham, Jr., CPA, Ph.D., is an associate profes-sor of accounting at Oregon State University. You can reach him at (541) 737-4028 and grahamr@bus.orst.edu. Gerald R. Chrobuck, CPA, is an accounting manager at the Puget Sound site of the Boeing Company’s Military & Missiles System business unit. You can reach him at (206) 662-2635 and gerald.chrobuck@PSS.Boeing.com.