David, VANSTONE, Maurice and WARDAK, Ali

Available from Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at:

http://shura.shu.ac.uk/10540/

This document is the author deposited version. You are advised to consult the

publisher's version if you wish to cite from it.

Published version

CALVERLEY, Adam, COLE, Bankole, KAUR, Gurpreet, LEWIS, Sam, RAYNOR,

Peter, SADEGHI, Soheila, SMITH, David, VANSTONE, Maurice and WARDAK, Ali

(2004). Black and Asian offenders on probation. Technical Report. Home Office.

Copyright and re-use policy

See

http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html

Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive

Home Office Research Study 277

Black and Asian offenders

on probation

Adam Calverley, Bankole Cole, Gurpreet Kaur, Sam Lewis, Peter Raynor,

Soheila Sadeghi, David Smith, Maurice Vanstone and Ali W ardak

The views expressed in this repo rt are tho se o f the autho rs, no t necessarily tho se o f the Ho me O ffice (no r do they reflect G o vernment po licy).

The Ho me O ffice Research Studies are repo rts o n research undertaken by o r o n behalf o f the Ho me O ffic e . They c o ve r the rang e o f sub je c ts fo r whic h the Ho me Sec re t a ry ha s re s p o n s i b i l i t y. O ther publicatio ns p ro d uc ed b y the Researc h, Develo pment and Statistic s Directo rate include Finding s, Statistical Bulletins and Statistical Papers.

The Research, Development and Statistics Directorate

RDS is part o f the Ho me O ffice . The Ho me O ff i c e ’s purpo se is to build a safe, just and to lerant so ciety in which the rights and resp o nsibilitie s o f individuals, families and co mmunities are p ro perly balanced and the pro tectio n and security o f the public are maintained.

RDS is also part o f N atio nal Statistics (N S). O ne o f the aims o f N S is to info rm Parliament and the citizen ab o ut the state o f the natio n and pro vide a windo w o n the w o rk and perf o rm a n c e o f g o vernment, allowing the impact o f g o vernment po licie s and actio ns to be assessed.

T h e re f o re –

R e s e a rch Development and Statistics Directorate exists to improve policy making, decision taking and practice in support of the Home O ffice purpose and aims, to provide the public and Parliament with information necessary for informed debate and to publish i nformation for future use.

First published 2 0 0 4

Applicatio n fo r repro ductio n sho uld be made to the Co mmunicatio ns and Develo pment Unit, Ro o m 2 0 1 , Ho me O ffice, 5 0 Q ueen Anne’s G ate, Lo ndo n SW 1 H 9 AT.

Forew ord

This repo rt presents the finding s o f a survey which was co mmissio ned to help info rm the d eve lo pme nt o f p ro b atio n wo rk w ith b la ck a nd Asia n o ffend e rs. Fo r interventio ns w ith o ffenders to be effective in reducing reo ffending , it is essential to understand no t o nly the facto rs directly asso ciated with o ffending (crimino g enic needs) but also ho w they vary fo r different g ro ups o f o ffenders. Hitherto , little has been kno wn abo ut ho w crimino g enic needs v a ry be tw e en d iff e re nt e thnic g ro ups. This survey a imed to e xa mine the ir c rimino g enic ne e d s, e xp lo re the ir vie w s o f p ro b a tio n sup e rvisio n a nd to info rm d e c isio ns a b o ut appro priate interventio ns.

In to ta l, 4 8 3 bla ck and Asian o ffenders were surveye d. The re s e a rch fo und that bla ck, Asia n and mixe d heritag e o ffend e rs sho w ed less evid enc e o f c rime-p ro ne attitudes a nd b elie fs, a nd lo w e r le ve ls o f se lf-re p o rted p ro b le ms tha n c o mp a riso n g ro up s o f w hite o ffenders. In additio n, o nly a third o f o ffenders wanted to be supervised by so meo ne fro m the sa me e thnic g ro up . The re w a s a lso ve ry limite d sup p o rt fro m tho se a tte nd ing pro g rammes fo r g ro ups co ntaining o nly members fro m mino rity ethnic g ro ups.

This repo rt is an impo rtant co ntributio n bo th to develo pment o f pro batio n practice and to w ider deb ates o n the treatment o f mino rity ethnic g ro ups in the crimina l justice syste m. F u rther re s e a rch is underw ay to inc rease o ur kno wledg e o f ‘ w hat wo rks’ fo r b lac k a nd Asian o ffenders.

Chlo e Chitty Pro g ramme Directo r

W e a re pa rticularly g ra teful to all tho se staff o f the N a tio nal Pro ba tio n Se rvic e, in the Directo rate and the areas, who helped us with info rmatio n and access; to all the members o f the Steering G ro up; to Ro bin Ellio tt and G ina Taylo r o f RDS; and particularly to all the pro batio ners who allo wed us to interview them, and shared their views and experiences so willing ly. W e ho pe this repo rt do es them justice.

RDS wo uld like to thank Co retta Phillips o f the Lo ndo n Scho o l o f Eco no mics fo r her peer review o f the paper that co ntained valuable advice and expertise.

Adam Calverley, Banko le Co le, G urpreet Kaur, Sam Lewis, Peter Rayno r, So heila Sadeg hi, David Smith, Maurice Vansto ne and Ali W ardak

Contents

Ackno wledg ements ii

Executive summary v

Chapter 1 Intro ductio n 1

Chapter 2 The co nduct o f the research 1 1

Chapter 3 Survey respo ndents and their crimino g enic needs 1 7

Chapter 4 Experiences o f pro batio n and pro g rammes 3 1

Chapter 5 So cial exclusio n and experiences o f criminal justice 4 1

Chapter 6 Co nclusio ns and implicatio ns 5 5

Appendix 1 So me pro blems o f fieldwo rk in the pro batio n service 6 1

Appendix 2 Additio nal tables 6 3

Executive summary

This stud y invo lve d interview s w ith 4 8 3 o ffe nd e rs und e r sup e rvisio n b y the Pro b a t i o n S e rvic e and identified by p ro ba tio n re c o rds as blac k o r Asian. The interviews co llec ted info rmatio n abo ut their ‘ crimino g enic needs’1; their experiences o f supervisio n o n co mmunity rehabilitatio n o rders and pro g rammes; their co ntact with o ther parts o f the criminal justice system; and their wider experiences o f life as black and Asian peo ple in Britain. The sample also included a number o f o ffenders who classified themselves as o f mixed ethnic o rig in, described in the repo rt as mixed heritag e.

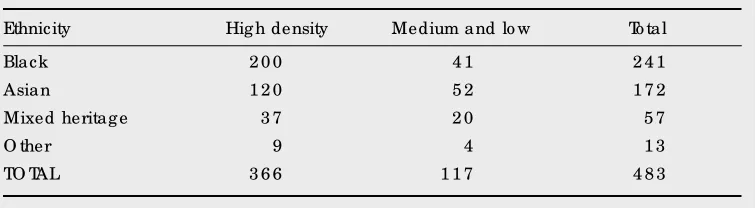

The 4 8 3 respo ndents included 2 4 1 black, 1 7 2 Asian, 5 7 mixed heritag e and 1 3 ‘ o ther’ o ffenders, drawn fro m a rang e o f areas with varying densities o f mino rity ethnic po pulatio n. They included 2 3 6 who were attending o r had been attending a pro g ramme, and 2 4 7 who were being o r had been supervised witho ut a pro g ramme. So me categ o ries o f o ffender and typ e s o f a re a w e re o ve rsamp le d to ensure tha t useful numbe rs w o uld b e availa ble fo r a na lysis, and the sa mp le w a s the n w e ig hte d to re flec t, a s fa r a s p o ssib le , the a c tual pro po rtio ns and lo catio ns o f mino rity ethnic peo ple in the natio nal caselo ad o f co mmunity rehabilitatio n o rders. Find ings are re p o rted o n the basis o f the weighte d sample exc ept where o therwise indicated.

Criminogenic needs

The main quantitative assessment o f crimino g enic needs was carried o ut using the CRIME-PICS II questio nnaire, which is desig ned to elicit info rmatio n abo ut crime-pro ne attitudes and be liefs and a bo ut so cial and p erso nal difficultie s experienced by o ffenders (‘ self-re p o rt e d pro blems’ ). Key finding s were:

● All three mino rity ethnic g ro ups (black, Asian and mixed heritag e) sho wed less evid ence o f crime-pro ne a ttitudes and beliefs, and lo we r levels o f se lf-re p o rt e d p ro b lems, than relevant co mpariso n g ro ups o f white o ffe nders. The diff e re n c e s between this survey sample as a who le and the main white co mpariso n g ro up were statistically sig nificant o n all subscales o f CRIME-PICS II.

● W ithin the mino rity ethnic sample, o ffenders o f mixed heritag e had the hig hest a ve ra g e sc o res o n mo st me a sure s o f c rime -p ro ne a ttitud e s and se lf-re p o rt e d pro blems, and Asians the lo west2.

● This evidence therefo re lends no suppo rt to the idea that o ffenders o n pro batio n who belo ng to mino rity ethnic g ro ups tend to have distinctively different o r g reater crimino g enic needs than white pro batio ners. This resembles the finding s o f o ther co mparative studies (reviewed in Chapter 3 ). Their experiences are likely to differ f ro m tho se o f white pro batio ne rs in o ther ways, ho wever, which are discussed belo w.

● The se find ing s sug g e st tha t the mino rity e thnic o ffe nd e rs in the sa mp le ha d received the same co mmunity sentences as white o ffenders who had hig her levels o f crimino g enic need . This finding , b ased o n sma ll b ut sta tistic ally sig nific ant d i ff e rence s, may have a number o f explanatio ns. Ho weve r, o ne way in which such a result co uld be pro duced is thro ug h so me deg ree o f differential sentencing . This co uld result in mino rity ethnic o ffenders with lo w crimino g enic needs facing a slig htly hig her risk tha n co mpara ble white o ffenders o f re ce iving a co mmunity sentence rather than a less serio us sentence. Ano ther po ssibility is that mino rity e thnic o ffe nd e rs w ith hig h ne ed s ma y b e le ss likely to rec eive a c o mmunity sentence than co mparable white o ffenders. These po ssibilities wo uld need to be investig ated thro ug h further research, but they also sug g est a need fo r co ntinuing vig ilance in relatio n to diversity issues in sentencing and in the preparatio n o f pre-sentence repo rts.

● O ffenders o n o rders with an additio nal requirement to attend a pro g ramme had slig htly lo we r sco res fo r crime-p ro ne attitude s and beliefs and fo r self-re p o rt e d p ro b le ms tha n tho se o n o rd i n a ry o rd e rs, a ltho ug h the d iff e re nc e w a s o nly sig nificant in relatio n to self-repo rted pro blems. There was no evidence that this was due to a pro g ra mme effect. The p ro g ramme g ro up had a hig he r averag e O ffe nd er G ro up Re c o nvic tio n Sc a le (O G RS) sco re , ho we ver, ind ica ting mo re previo us co nvictio ns.

● T h e re w a s so me ind ic a tio n tha t Asia n o ffe nd e rs w e re le ss like ly to a c c e ss p ro g ra mmes, w hich may ha ve b ee n pa rtly due to their lo wer a verag e O G RS sco res.

Experiences of probation

The ma jo rity o f re sp o ndents’ co mments o n their e xperie nce s o f p ro b a tio n w e re b ro a d l y favo urable, in line with o the r co nsumer stud ies co ve ring mainly white pro ba tio ners. Key finding s were:

● A g o o d pro batio n o fficer was o ne who treated peo ple under supervisio n fairly and with respect, listened to them and sho wed understanding .

● Abo ut a third (3 5 %) wanted to be supervised by so meo ne fro m the same ethnic g ro up, 5 6 per cent said that it made no difference, ten per cent did no t kno w whether it mattered, and two per cent were o ppo sed to the idea. (These fig ures do no t add up to 1 0 0 because a small number o f respo ndents said that having a mino rity ethnic superviso r mig ht be a g o o d thing and a bad thing .)

● P ro g ramme s also attracted favo urable co mments, altho ug h a substantial mino rity o f p a rtic ip ants (2 2 %) re p o rted no t liking anything a b o ut their pro g ra mme. Mo st (8 6 %) pro g ramme participants said that the g ro up leaders had treated them fairly.

● O f tho se who attended p ro g ra mmes, ab o ut a third (3 3 %) sa id tha t the ethnic co mpo sitio n o f the gro up was unimpo rtant; o f the re m a i n d e r, mo st said it sho uld be mixed. There was very limited support (only eight respo ndents, all fro m areas with hig h ethnic mino rity po pula tio ns, equivale nt to a w eig hte d five p er ce nt o f the p ro gramme sample) fo r gro ups containing o nly members fro m minority ethnic gro u p s .

● These finding s tended to suppo rt a po licy o f running mixed pro g ramme g ro ups rather than g ro ups c o nsisting o nly o f mino rity ethnic o ffend e rs. Mixe d staff i n g co uld be advantag eo us but was no t tho ug ht by mo st respo ndents to be essential.

● The indicatio ns re g a rding ‘ sing leto n’ plac ements where o nly o ne me mbe r o f a g ro up is fro m an ethnic mino rity are less clear. Eleven per cent o f the 9 5 per cent o f p ro g ra mme p a rtic ip a nts w ho d e sc rib e d the e thnic c o mp o sitio n o f the ir pro g ramme g ro up experienced ‘ sing leto n placements’ , and this pro ved to be an u n c o m f o rta b le e xp e rie nc e fo r so me . N e ve rthe le ss, in ‘ lo w d e nsity’ a re a s , sing le to n p la c e me nts w o uld so me time s b e the o nly a lte rna tive to e ff e c t i v e l y exc luding mino rity e thnic o ffe nde rs fro m p ro g ra mme s, whic h w o uld itse lf b e undesirable.

Social disadvantage

● The interviews explo red a number o f areas o f po ssible so cial disadvantag e, and there was evidence o f substantial so cial exclusio n and disadvantag e in relatio n to emplo yment, inco me, educatio n and training .

● H o w e v e r, re sp o nd e nts w e re no t, o n a ve ra g e , sig nific a ntly mo re so c ia lly d isa dvantag e d than white o ffend ers o n pro ba tio n. Black and Asia n peo ple in g eneral are kno wn to experience mo re disadvantag e than white peo ple in Britain (see Chapter 5 ), but these differences did no t appear clearly amo ng the smaller selected po pulatio n o f o ffenders o n pro batio n. Black, Asian, and mixed heritag e p ro b a tio ne rs a ll sho w e d sub sta ntia l e vid e nc e o f d isa d va nta g e , a s w hite pro batio ners also did in o ther studies.

● W ithin the sa mp le , the re w e re no tic e a b le d iff e re nc e s in le ve ls o f so c ia l disadvantag e between mino rity ethnic g ro ups. Fo r example, while 4 1 per cent o f the sa mp le re p o rte d a g e ne ra lly ne g a tive e xp e rie nc e o f sc ho o l, Ind ia ns, Pakistanis and black Africans were less likely to have had a neg ative experience o f scho o l than Bang ladeshi, black Caribbean o r mixed heritag e o ffenders. Thirty-five p e r c e nt o f mixe d he rita g e o ffend e rs ha d b e e n in lo c a l a utho rity c a re , co mpared to 2 2 per cent o f black Caribbeans, nine per cent o f black Africans, and fo ur per cent o f Asians. (The co rrespo nding fig ure fo r white pro batio ners is g iven in o ther studies as 1 9 per cent.)

● W he n a ske d a b o ut re a so ns fo r d isa d va nta g e , ma ny re sp o nd e nts a ttrib ute d a dverse experie nces, pa rticularly in relatio n to e mplo yment a nd e duca tio n, to racial prejudice, ho stility o r discriminatio n.

Experiences of criminal justice

Many respo ndents repo rted experiences o f unfair treatment in vario us parts o f the criminal justice system. Key finding s included the fo llo wing :

● W hile pro batio n staff were g enerally described as behaving fairly, o ther parts o f the c rimina l justice syste m, p a rtic ula rly the p o lice , we re d e sc ribe d much le ss favo urably.

● This evidence sug g ests that the Pro batio n Service sho uld be aware that neg ative experiences o f criminal justice are likely to affect perceptio ns o f the leg itimacy o f the system, and this in turn can affect mo tivatio n and co mpliance.

● Visible re p re se nta tio n o f mino rity ethnic c o mmunities in the staffing o f criminal justice ag encies was seen as helpful.

● Pro batio n staff also need to be aware o f the particular needs and experiences o f o ffenders o f mixed heritag e, who have received less research and po licy attentio n than o ther ethnic mino rity g ro ups.

Other implications

● It was clear fro m co ntacts with Pro batio n Service manag ers and staff that there was a g eneral awareness o f the need to avo id, at o ne extreme, the ‘ co lo ur-blind’ practic e that ig no res diversity o f culture, expe rience and o ppo rt u n i t y. Ho wever, this study has also demo nstrated the rang e o f views and experiences to be fo und w ithin e ac h mino rity ethnic g ro up , as we ll a s so me diff e re nc es in re s p o n s e s between black, Asian and mixed heritag e pro batio ners.

● This sug g ests that it is impo rtant no t to treat mino rity ethnic status as a defining id entity fro m w hic h p e rso na l c ha ra c te ristic s, e xp e rie nce s a nd ne e d s c a n b e re lia b ly infe rre d . This, ho we ver b e nig nly intend e d , is itse lf a fo rm o f e thnic stereo typing .

● Re sp o nde nts in this stud y e xp ec ted to b e trea te d fa irly, a s individ ua ls, as ‘ a no rmal perso n’ , by staff who listened to them and respected their views. Po licies and practice the re f o re need to be info rme d by awarene ss o f diversity, but no t based o n untested assumptio ns abo ut what diversity implies.

Chapter 1:

Introduction

This repo rt presents the finding s o f a study which aimed to identify the crimino g enic needs o f black and Asian o ffenders, to explo re their views abo ut pro batio n supervisio n, and to info rm decisio ns abo ut appro priate service pro visio n. The study was co mmissio ned ag ainst the b ackg ro und o f lo ng -sta nding c o nce rn abo ut the po ssib ility that pe o p le fro m mino rity ethnic g ro up s may be subject to disadva ntag e o us treatment a t all stag es o f the criminal justic e p ro cess, eve n if this do e s no t re sult fro m o vert rac ist disc riminatio n (Phillips a nd B ro w n, 1 9 9 8 ). It wa s this c o nc ern tha t led to the pro visio n in Se ctio n 9 5 o f the 1 9 9 1 Criminal Justice Act that the Ho me O ffice sho uld publish annually ‘ info rmatio n… facilitating the pe rf o rmance o f suc h perso ns [tho se eng ag ed in the administratio n o f justice] o f their duty to avo id discriminating ag ainst any perso ns o n the g ro und o f race o r sex o r any o ther impro per g ro und’ . As the Fo rewo rd to the mo st recent repo rt, Race and the Criminal Justice System, states:

A mo de rn, fa ir, e ffe ctive c rimina l justice system is no t p o ssib le w hilst sig nific ant se ctio ns o f the p o p ulatio n perc e ive it a s disc rimina to ry and lac k c o nfid enc e in it delivering justice (Ho me O ffice, 2 0 0 2 a: 1 ).

W e review belo w the evidence that peo ple fro m mino rity ethnic g ro ups perceive the criminal justice system in this lig ht.

Ethnic minorities and criminal justice

t re ate d fairly a nd p o lite ly, o r that the y w e re sa tisfied w ith the b e havio ur o f the po lic e (Clancy et al., 2 0 0 1 ). Yo ung black men (under the ag e o f 2 5 ) were the g ro up mo st likely to be sto pped by the po lice, and while being black was no t fo und to increase the likeliho o d o f being sto pped while o n fo o t (a finding unlike tho se o f the Surveys o f 1 9 9 3 and 1 9 9 5 ), it did increase the chances o f being sto pped while in a car.

In relatio n to victimisatio n, the 2 0 0 0 British Crime Survey fo und that while peo ple fro m mino rity ethnic g ro ups do no t experience hig her rates o f victimisatio n than whites living in similar areas, they – particularly Pakistanis and Bang ladeshis – are mo re likely say that they are very wo rried abo ut beco ming victims o f crime, and mo re likely to interpret crimes o f which they have been victims as racially mo tivated (Clancy et al., 2 0 0 1 ). Amo ng peo ple who repo rted crimes to the po lice, tho se fro m mino rity ethnic g ro ups were less likely than whites to express satisfactio n with the po lice respo nse. Being a victim o f crime predicted a lo w e r ra ting o f po lic e p e rf o rma nc e: o nly 3 3 p e r c e nt o f victims o f rac ia lly mo tiva te d incidents tho ug ht that the po lice were do ing a g o o d jo b.

Much discussio n o f the po ssibility that peo ple – and in particular black peo ple – in mino rity ethnic g ro ups are discriminated ag ainst in criminal justice decisio n-making has centred o n the dramatic o ver-representatio n o f black peo ple in the priso n po pulatio n. The Ho me O ffice (2 0 0 2 a) estimates that in 2 0 0 0 the rate o f incarceratio n o f black males was abo ut nine times as hig h as that fo r white males, and abo ut fifteen times as hig h fo r black as fo r white fema les. O nly so me o f the d isp ro p o rtio n c a n b e e xp la ine d b y the p re se nce in the se p o p ula tio ns o f fo reig n na tio na ls, many a rre ste d o n entry into Brita in; the re rema ins a pro blem abo ut ho w far the discrepancy can be explained by differences in the vo lume and types o f crime co mmitted by black peo ple (co mpared with bo th whites and Asians), and ho w far it is to be attrib ute d to diff e rential and p o ssibly d iscriminato ry treatme nt in the criminal justice system.

children in all categ o ries are mo re likely than any o ther ethnic g ro up to be excluded fro m scho o l. All these fa cto rs – p o ve rt y, lo w e d uc atio na l a c hie ve me nt, pro b le ms a t sc ho o l, une mp lo yme nt – c o uld p la usib ly b e a sso c ia te d w ith a n inc re a se d risk o f c rimina l invo lvement.

There is also evidence, ho wever, that mino rity ethnic peo ple may be (further) disadvantag ed by their treatment by criminal justice ag encies, and that this applies especially to blacks. Since they – and to a lesser extent Asians – are mo re likely to be sto pped by the po lice and mo re likely to be arrested (Ho me O ffice, 2 0 0 2 a), their chances o f beco ming available to be p ro ce sse d b y the c rimina l justice syste m a re hig her than tho se o f whites. The re is a lso co nsistent evidence that o nce they are in the system the kinds o f decisio ns made o n black and Asian peo ple differ fro m tho se made o n whites (Phillips and Bro wn, 1 9 9 8 ; Bo wling and Phillips, 2 0 0 2 ). Black peo ple are mo re likely to be charg ed rather than cautio ned, mo re likely to be charg ed with mo re rather than less serio us o ffences, and mo re likely (perhaps as a co nsequence) to be remanded in custo dy. Bo th blacks and Asians are mo re likely than w hites to plea d no t g uilty, a nd mo re likely to b e a c quitte d. If co nvicted o f o ffe nc es o f vio lence, they are mo re likely to receive custo dial sentences. The o verall pattern sug g ests that, certainly in the earlier stag es o f the criminal justice pro cess, the decisio ns made o n mino rity ethnic p eo p le d iffer fro m tho se ma d e o n w hite s in a w a y tha t inc re a se s the ir chances o f being drawn further into the system, and ultimately increases the risk o f custo dy.

In its review o f the evidence and statement o f intended actio n, the Ho me O ffice (2 0 0 2 b, p. 1 0 ) itself co ncludes that the differences ‘ are such that it wo uld be implausible to arg ue that no ne are due to discriminatio n’ . W hile reco g nising that facto rs o ther than racism may have co ntrib ute d to these d iff e rence s, the Ho me O ffice sta te me nt g o e s o n to de scribe a ctio n already taken o r in pro spect to reduce discriminatio n in the criminal justice system and to i m p ro ve und e rsta nd ing o f the p ro c e sse s invo lve d . The a c tio n ta ke n inc lud e s the implementatio n o f the Race Relatio ns (Amendment) Act in April 2 0 0 1 , which bring s mo st c riminal justice ag encies under the sco pe o f leg isla tio n that makes discriminatio n o n the basis o f race illeg al. Further actio n invo lves the full implementatio n o f the reco mmendatio ns o f the Mac pherso n Re po rt (1 9 9 9 ) o n the murd er o f Step he n La wrence , re s e a rc h in the Cro wn Pro secutio n Service and the Lo rd Chancello r’ s Department (no w the Department fo r Co nstitutio nal Affairs) o n po ssible areas o f discriminato ry practice, research and wo rk o n the develo pment o f g o o d practice in the N atio nal Pro batio n Service and the Yo uth Justice B o a rd, and the pro mo tio n o f a nti-racist prac tic e in the Priso n Service. The Ho me O ff i c e (2 0 0 2 b) also anno unced the establishment o f a new unit with a cro ss-departmental brief to wo rk to wards a better understanding o f patterns o f o ver- and under-representatio n o f ethnic mino ritie s in the crimina l justic e syste m, id e ntify b a rrie rs to imp ro ve me nt, p ro p o se a

p ro g ramme o f a ctio n to elimina te d isc rimina tio n, draw to g e the r a nd d isse mina te g o o d practice, and make reco mmendatio ns o n what statistics sho uld be co llected and ho w they sho uld b e public ise d. Issue s o f rac ism a nd d iscriminatio n in c riminal justic e a re, then, reco g nised as an impo rtant po licy prio rity.

Race issues and the Probation Service

Such issue s are o f c urrent c o nc ern in the Pro ba tio n Se rvice a s in o the r c rimina l justic e ag encies. Intro ducing a repo rt o n the service’ s wo rk o n race issues, the then Chief Inspecto r o f Pro batio n declared himself ‘ dismayed by many o f the finding s’ , especially tho se which sug g e ste d d isp a ritie s b e tw e e n the a p p ro a c h to w o rk w ith w hite a nd mino rity e thnic o ffe nd e rs (He r Ma jesty’s Inspe cto ra te o f Pro ba tio n, 2 0 0 0 : 1 ). Sub se q uently Po w is and W almsley (2 0 0 2 ) underto o k a study o f current and past pro batio n pro g rammes fo r Black and Asian o ffenders with a view to extracting lesso ns fo r the develo pment o f practice. The research which is the subject o f this repo rt is intended to co mplement Po wis and W almsley’ s wo rk by adding to kno wledg e o f Black and Asian men’ s perceptio ns o f pro batio n and their ideas o n what kinds o f practice are likely to be mo st helpful. The research is to be further co mplemented by the N atio nal Pro batio n Directo rate, which has identified five mo dels o f w o rking with Bla c k and Asia n o ffe nd e rs and is c o mmitte d to testing their eff e c t i v e n e s s (Po wis and W almsley, 2 0 0 2 , p. 4 4 ).

fo llo w ing rio ts the re in 1 9 8 1 , a d o pted a ‘ c o mmunity-b a se d a nd d e ta c he d ’ a p p ro a c h (Lawso n, 1 9 8 4 ). In 1 9 8 4 , the Asso ciatio n o f Black Pro batio n O fficers (ABPO ) held its first g eneral meeting , and in 1 9 8 7 the N atio nal Asso ciatio n o f Asian Pro batio n Staff (N AAPS) was fo rmed, o n the basis that Asian perspectives were no t adequately co vered by the term ‘ black’ (HMIP, 2 0 0 0 ).

Previo us research o n the needs and perceptio ns o f mino rity ethnic peo ple supervised by the Pro batio n Service has typically been o n a small scale. Fo r example, Lawrence et al. (1 9 9 2 ), wo rking in co llabo ratio n with the then Inner Lo ndo n Pro batio n Service (ILPS), interviewed a sample o f black o ffenders, black and white wo rkers, and staff o f interested ag encies, and s c rutinised 5 9 c o urt re p o rts. The y c o nc lud e d that mo st blac k o ffend e rs wa nte d spe cial pro visio n, but also o bserved that po pular perceptio ns o f this client g ro up were ‘ wide o f the mark. Indeed, in many respects, bo th with reg ard to the so cial characteristics o f the black client g ro up seen by ILPS and patterns o f o ffending , black clients do no t differ appreciably fro m white clients’ (p. 7 ). Jeffers (1 9 9 5 ) interviewed 4 4 o ffenders (2 8 mino rity ethnic and 1 6 w hite me n a nd w o men) a nd o b serve d c o ntac t be tw e en o ffic ers a nd o ffend e rs. He co ncluded that black and white o ffenders shared a desire fo r respect, trust, credibility and practical assistance, and o bserved that black o ffenders’ perceptio n o f pro batio n ‘ may be as much to do with its symbo lic lo catio n, relative to the criminal justice system as a who le and the d e g ree to whic h this wider syste m is seen as racially discriminating ’ (p. 3 3 ). Jeff e r s identified two characteristic pro batio n appro aches: firstly, ‘ minimal manag erial anti-racism and equal o ppo rtunities strateg ies’ , i.e. the recruitment o f black staff, equality o f treatment a nd ethnic mo nito ring ; and seco nd, a ‘ mo re po litic ised a nti-rac ist p ro ject’ invo lving , fo r example, the develo pment o f black empo werment g ro ups desig ned to ‘ co unter the neg ative self imag es black o ffenders may have thro ug h the medium o f g ro upwo rk and help them take co ntro l o f their lives thro ug h increasing their self esteem’ (p. 1 6 ). The sco pe and nature o f special pro visio n fo r mino rity ethnic o ffenders are discussed at g reater leng th belo w.

In a rec ent stud y o f pre -sentenc e re p o rts o n Asia n and white defenda nts in the no rth o f England, Hudso n and Bramha ll (2 0 0 2 ) re p o rted serio us deficiencies in the re c o rding o f data o n o ffende rs’ ethnicity, a po int which is discusse d in mo re d etail belo w. They also fo und i m p o rtant diff e rences in the style and co nte nt o f re p o rts. Rep o rts o n Asians tended to be ‘ thinne r’ , in the sense that they g ave less info rmatio n, and the y we re mo re likely to use ‘ distancing’ lang uag e when discussing info rmatio n g iven by the defendant (‘he tells me that… ’, and the like). Asian de fendants were less likely to be presented as sho wing remo rse and accep ting respo nsibility fo r the o ffence, and their pro blems were mo re o ften attributed to their individual characteristics than to externally o bservable difficultie s such as substance misuse. T h e re were also diff e rences in sentencing pro po sals: co mmunity punishment o rd ers were mo re

likely to be pro po sed fo r Asians, and co mmunity rehabilitatio n o rders fo r whites; and re p o rt s o n Asians were mo re likely to ma ke no po sitive pro po sal, o r to present a custo dial sentence as inevitable. The autho rs concluded that Asians re ceived co mmunity punishment o rde rs and sho rt custo dial sentences in case s where whites wo uld receive co mmunity rehab ilitatio n orders, and that this disparity in sentencing was a result o f the pro po sals in re p o rts. These co nclusio ns are based o n a rela tively sma ll sample and o n re p o rts in o ne pro batio n are a, but the study sug g e sts, a s did the HMIP re p o rt (2 0 0 0 ) that there is no ro o m fo r co mp lac enc y in the P ro batio n Se rvice abo ut its practice with mino rity ethnic o ff e n d e r s .

Developments in policy and practice

Pro batio n po licy and practice o n mino rity ethnic o ffenders have no t develo ped smo o thly o r c o n s i s t e n t l y. O n the po licy level, the Pro batio n Inspe cto rate (HMIP, 2 0 0 0 ) no te d that the impo rtance o f anti-discriminato ry practice was stressed in the 1 9 9 2 N atio nal Standards fo r pro batio n, was much less evident in the 1 9 9 5 versio n, and became mo re pro minent ag ain in 2 0 0 0 . The Inspe cto rate also o bserved that eq ual o p po rtunities and anti-discriminatio n issue s were no t mentio ne d in the three-ye ar plans fo r the service co ve ring 1 9 9 6 -2 0 0 0 . T h e re is a lso evid e nc e o f c o ntinuing (a nd w o rsening ) p ro b le ms o f da ta c o lle c tio n a nd mo nito ring , which are hig hly relevant to the present study: altho ug h such data have o fficially been co llected since 1 9 9 2 , the Ho me O ffice (2 0 0 2 a) was unable to include ethnic data o n perso ns supervised by the Pro batio n Service in its annual presentatio n o f statistics o n race and the criminal justice system, and o bserved (p. 3 ): ‘ O ver recent years the pro po rtio n o f ethnic data missing has risen substantially’ . It is therefo re no t surprising that data o n mino rity ethnic p ro b a tio ners in Pro ba tio n Sta tistic s p ro ve d a n unre lia ble so urce in the p la nning stag es o f this study.

pro visio n and abo ut the mixing o f black and Asian o ffenders, and inco nsistency o ver ethnic definitio ns. Po wis and W almsley identified 1 3 pro g rammes that had run at so me time, in ten d i ff e re nt p ro b a tio n a re a s, b ut o nly five tha t w e re running a t the time o f the surv e y. Pro g rammes were categ o rised as Black Empo werment G ro ups, Black Empo werment within G e ne ra l O ffe nd ing , Bla c k Emp o w e rme nt a nd Re inte g ra tio n, a nd O ffe nc e Sp e c ific Pro g rammes. Staff were po sitive abo ut the pro g rammes, but the researchers co ncluded:

There are many arg uments that suppo rt running separate pro g rammes but also so me that advo cate mixed g ro up-wo rk pro visio n. There is, as yet, little empirical evidence to substantiate either po sitio n (p. 1 1 ).

Mo re recently, Durrance and W illiams (2 0 0 3 ) have arg ued that there are g o o d g ro unds fo r believing that so me mino rity ethnic o ffenders co uld benefit fro m special pro visio n o f the kind aimed at by pro g rammes co ntaining an element o f empo werment, and that it is premature to suppo se that ‘ what wo rks’ with white o ffenders will by definitio n wo rk with o ther ethnic g ro ups. They sug g est that the experience o f racism may have a neg ative impact o n the self-co ncept o f black and Asian peo ple, and that wo rk may therefo re be required to enable o r empo wer them to acquire a mo re po sitive sense o f identity. They use their o wn evaluatio n finding s to sug g est that empo werment is a feasible and po tentially valuable appro ach to wo rking with o ffenders who have experienced so me fo rm o f institutio nalised discriminatio n.

The present research: aims and design

The present study was intended to fill so me o f the g aps in kno wledg e identified by Po wis and W almsley, and to pro vide a stro ng er empirical base to info rm arg uments abo ut the best fo rm o f pro visio n fo r mino rity ethnic o ffenders. Its aims were:

● to co llect so me systematic info rmatio n o n the crimino g enic ne eds o f black a nd Asian o ffenders;

● to explo re the view s o f bla ck and Asian o ffe nders abo ut their experienc es o f s u p e rvisio n by the Pro b atio n Service, particularly in the ir current pro ba tio n (o r co mmunity rehabilitatio n) o rder, and their experiences o f pro batio n pro g rammes; and

● to draw an o verall picture o f the pro blems faced by black and Asian o ffenders and ho w they respo nd to attempts to address them.

The research desig n o rig inally envisag ed co nducting 5 0 0 structured interviews with black and Asian men currently o n pro batio n o r co mmunity rehabilitatio n o rders. W o men were no t included in the Ho me O ffice’ s specificatio n fo r the research. In the event, 4 8 3 interviews were co nducted that pro duced valid data fo r analysis; practical difficulties in the co nduct o f the fieldw o rk a re d iscussed in the fo llo w ing c ha pte r. The stud y did no t inc lude a w hite co mpariso n g ro up: co mpariso ns are made with data o n white o ffenders fro m o ther studies.

The intended sample was hig hly structured, by ethnicity, area, and type and stag e o f o rder. The aim was to interview 2 0 0 o ffenders o n o rders with 1 A co nditio ns – i.e. that they sho uld participate in a g ro upwo rk pro g ramme – and 3 0 0 o n ‘ standard’ o rders. The sample was to be made up o f 2 0 0 o ffenders reco rded in pro batio n reco rds as ‘ Asian’ and 3 0 0 reco rded as ‘ black’ ; therefo re 8 0 Asian and 1 2 0 black o ffenders subject to 1 A co nditio ns were to be i n t e rvie w ed, a nd 1 2 0 Asia n and 1 8 0 b lac k o ffe nd ers subje ct to standa rd o rd e r s3. The sa mp le o f p ro b a tio n a re a s w a s c ho se n to c o ve r a re a s w ith hig h, me d ium a nd lo w pro po rtio ns o r ‘ densities’ o f mino rity ethnic peo ple o n pro batio n4 as a percentag e o f the to tal pro batio n caselo ad. The Ho me O ffice assig ned pro batio n areas to a density categ o ry o n the basis o f fig ures pro vided by the areas. Sample siz es fo r each area were arrived at o n the basis o f a o ne-seventh sample o f the estimated to tal po pulatio n o f black and Asian peo ple o n pro batio n in hig h density areas, o ne-third in medium density areas, and o ne-half in lo w density areas. This sampling strateg y was ado pted to ensure adequate representatio n in the sample o f o ffenders fro m each type o f area. Fo r similar reaso ns, so me o versampling o f Asian o ffenders was built into the sampling strateg y. The sample number fo r each area fo r bo th 1 A and standard o rders was, as far as po ssible, divided by fo ur to co ver o ffenders near the start o f o rders, tho se at an intermediate stag e, tho se co ming to the end o f an o rder, and tho se who had been breached fo r failing to co mply with their o rder’ s requirements5. The interviews actually co nducted bro adly fo llo wed the sampling strateg y, with adjustments as necessary to appro ximate the targ et o f 5 0 0 interviews in to tal.

3 . The intervie w sched ule aske d re spo nde nts to ca teg o rise their ethnic o rigin a s o ne o f: b lack Afric an, blac k C arib bea n, bla ck O ther, Pa kista ni, Bang la deshi, Ind ian, Asia n O ther, mixe d he ritag e a nd O the r, w hic h is co nsistent with the definitio ns o f ethnicity used in the 2 0 0 1 Po pulatio n Census.

4 In this repo rt we have g enerally used the o ld-fashio ned term ‘ pro batio n o rder’ rather than the mo re cumberso me co mmunity rehabilitatio n o rder, since the fo rmer was mo re readily understo o d by respo ndents, and we suspect it will still be mo re familiar to many readers.

The structure of the report

Chapter 2 describes the co nduct o f the fieldwo rk fo r the research and discusses so me o f the pro blems enco untered and the reaso ns fo r them; further material o n this is in Appendix 1 . C hapter 3 de scribes the basic demo g raphic c haracteristics o f the sample and beg ins to explo re the questio n o f whether the crimino g enic needs o f black and Asian o ffenders are d istinc t fro m tho se o f w hite o ffe nd e rs. C ha p te r 4 summa rise s re sp o nd e nts’ vie w s o f p ro b a tio n a nd p ro g ra mme s. C ha p te r 5 d isc usse s e vid e nc e o f so c ia l e xc lusio n a nd d e p riva tio n a mo ng re sp o nd e nts, a nd the ir e xp e rie nc e s o f the c rimina l justic e syste m. Chapter 6 reviews the finding s and discusses implicatio ns fo r pro batio n po licy and practice.

Chapter 2:

The conduct of the research

Planning and organisation

The research co ntract beg an o n 1 Aug ust 2 0 0 1 . The research team desig ned 8 0 0 flyers a nd 5 0 0 la rg e co lo ur po ste rs to publicise the pro ject; the se w ere fo r distributio n in the p ro batio n o ffice s taking part in the study, and described the nature a nd d uratio n o f the research, its main aims, and the staff invo lved. The team distributed these materials to the rele va nt p ro b atio n area s, a nd pro duce d se pa ra te info rma tio n shee ts fo r o ffe nd ers and pro batio n o fficers. A fo rm was pro duced o n which o ffenders were to indicate their co nsent to the interview and ackno wledg e receipt o f the £ 1 0 paid fo r each interview in reco g nitio n o f the time and effo rt invo lved.

The pro ject required nine researchers in fo ur g eo g raphically dispersed universities to wo rk effectively as a team, and to maintain co ntact with the Ho me O ffice, the N atio nal Pro batio n Directo rate (N PD), and the vario us pro batio n areas invo lved. The research was intro duced to the participating areas by a Diversity W o rksho p, which was o rg anised by the Research, Develo pment and Statistics Directo rate o f the Ho me O ffice (RDS) and the N PD, and held in Lo ndo n in O cto b er 2 0 0 1 . RDS fo rmed a Steering G ro up including me mbe rs o f N APO , ABPO and N AAPS6to info rm and suppo rt the research.

Two impo rtant tasks fo r the preliminary perio d o f the research were to ag ree a sampling stra te g y a nd d e ve lo p a d a ta c o lle c tio n instrument to b e use d in p ilo t inte rvie w s a nd mo dified as necessary. The hig hly structured nature o f the sample as o rig inally planned has been described in Chapter 1 . The breakdo wn o f the targ et fig ure by area is sho wn in the first co lumn o f fig ures in Table 2 .1 , which g ives the targ et sample number fo r each area, categ o rised by the ‘ density’ o f the mino rity ethnic po pulatio n; the seco nd co lumn sho ws the number o f interviews eventually achieved. (The targ et fig ures were set o n the understanding that the team mig ht need to be flexible abo ut numbers acro ss areas in o rder to achieve the intended o verall sample.)

In the first fe w weeks o f the pro ject, the team also wo rked to develo p a data co llectio n instrument – essentially an interview schedule – that wo uld address the research questio ns spe cified fo r the pro ject. The aim was to pro duce an instrume nt that co uld capture bo th

quantitative and qualitative data. The schedule co nsisted o f five main sectio ns, fo llo wing an intro ducto ry set o f questio ns that co vered basic perso nal details and info rmatio n abo ut the c u rrent o rd er a nd p ast e xpe rie nc es o f p ro ba tio n sup ervisio n. The first se ctio n c o ve re d experiences o f individual supervisio n and ideas o n what co nstituted helpful and appro priate pro batio n practice. The seco nd dealt with experiences o f pro g rammes, and was therefo re no t re le va nt to a ll intervie w ee s. It e xp lo re d p e rc ep tio ns o f the p urp o se a nd va lue o f p ro g ra mmes a nd e xp e rie nc e s o f b e ing a me mb e r o f a g ro up . The third sec tio n w a s co ncerned with the interviewee’ s current situatio n; it was mainly co ncerned with ho using , e mp lo yme nt, fa mily life , and d rug a nd alco ho l use . The C RIME-PIC S II instrument w a s a d m i n i s t e re d after this se t o f questio ns (se e C hapter 3 ). The fo llo w ing se ctio n used the CRIME-PICS respo nses to explo re interviewees’ crimino g enic needs, their perceptio ns o f why they ha d g o t into tro uble , and wha t cha ng e s they tho ug ht wo uld he lp them stay o ut o f t ro ub le in future. The fifth and final sectio n dealt with exp erience s o f the criminal justice system, bo th as an o ffender and, where relevant, as a victim.

The conduct of the research

The members o f the research team invo lved in interviewing were a diverse g ro up in terms o f g ender, ethnicity and culture. The majo rity7 o f the interviews were co nducted by black and Asian re s e a rchers, and e ach re s e a rc he r interviewe d o ffend ers fro m a ll e thnic g ro ups to g uard ag ainst biases resulting fro m interviewers’ ethnicity. There were very few indicatio ns o f differences in respo nse patterns o n acco unt o f interviewers’ ethnicity (but see Chapter 4 fo r a d isc ussio n o f tho se tha t w e re fo und ). A lso , c he c ks w e re ma d e p e rio d ic a lly fo r c o nsiste nt d iff e renc e s a mo ng inte rvie we rs in the typ e and quality o f d ata o b ta ine d in interviews, and no ne were fo und.

The schedule was pilo ted and mo dified in N o vember 2 0 0 1 . Fo urteen pilo t interviews8were held in pro batio n o ffices in Manchester and Cardiff, and lasted fro m o ne ho ur and fifteen minutes (the sho rtest) to two ho urs and ten minutes. Final re visio ns to the sched ule we re made fo llo wing the pilo t and further discussio n in a Steering G ro up meeting . The schedule subsequently pro ved a ro bust and reliable data co llectio n instrument.

The experience o f pilo ting the schedule was useful no t o nly fo r allo wing impro vements to be made to the interview sche dule b ut fo r sho wing that the pro cess o f fieldw o rk a nd data co llectio n wo uld be much mo re co mplex than we had expected. The main reaso n fo r this

was that (as we mig ht have predicted, g iven the Ho me O ffice’ s o wn criticisms o f the quality o f pro batio n data o n ethnicity, discussed in Chapter 1 ) the data held centrally in pro batio n areas had pro ved to be inaccurate and o ften o ut o f date; this meant, amo ng o ther thing s, that it was impo ssible accura te ly to ide ntify o ffe nd ers in the categ o ries re q u i red fo r strict a d h e renc e to the samp ling stra teg y. A numb er o f o ther prac tica l le sso ns, re i n f o rc ed by subsequent experience, were drawn fro m the pilo t study. Firstly, it was clear that research i n t e rvie ws were much mo re like ly to be succ essfully a rrang ed a nd co nducted whe n they immediately fo llo wed o r preceded an appo intment with the o ffender’ s pro batio n superviso r. S e c o n d l y, w e lea rne d tha t w e o ug ht to expe ct a hig h ra te o f no n-a tte nd a nce even fo r interviews arrang ed in this way, and that the appro ach to sampling needed to take acco unt o f this, and be g uided by co nsideratio ns o f o ppo rtunity and feasibility. Thirdly, it was clear even fro m the pilo t that o ur presence as researchers co uld quickly beco me irkso me to busy pro batio n staff, if, fo r example, it was necessary to arrang e mo re than o ne appo intment w ith an o ff e n d e r. So me o f the d ifficulties e nco untered in the c o urse o f the re s e a rch are discussed further in Appendix 1 .

In o rd er to ma inta in a re a so na b le ra te o f p ro g re ss to w a rd s the ta rg e t fig ure o f 5 0 0 i n t e rview s, a dd itio nal staff we re re c ruited o n a se ssio na l b asis by the G la mo rg a n and Linco ln teams, and co nducted a to tal o f 4 1 interviews. It was also necessary to diverg e fro m the targ et fig ures fo r each area when numbers apparently unavailable fo r interview in o ne area co uld be made up in ano ther. It was also decided to include a relatively small number o f interviews (5 3 ) with o ffenders who , whilst no t subject to a pro batio n o rder, were able to discuss the pro batio n element o f a different dispo sal (usually a co mmunity punishment and rehabilitatio n o rder).

Ta ble 2 .1 sho w s the fina l b rea kdo wn o f inte rvie ws by area , and c o mp a re s the ta rg e t numbers with tho se actually achieved.

Table 2.1:

Target and actual interview numbers by area

Typo lo g y o f areas O ffenders: targ et sample N o f interviews achieved Hig h density

Bedfo rdshire 9 1 1

G reater Manchester 3 0 3 8

Leicestershire 9 1 1

Lo ndo n 1 9 1 2 1 0

N o tting hamshire 1 3 1 4

Thames Valley 1 8 1 8

W est Midlands 7 8 6 4

Subto tal 3 4 8 3 6 8

Medium density

Avo n and So merset 1 7 1 5

Hertfo rdshire 6 3

W arwickshire 7 2

West Yo rkshire 5 2 4 1

W iltshire 6 4

Subto tal 8 8 6 5

Lo w density

Devo n/ Co rnwall 4 5

Essex 7 3

Lancashire 3 1 2 3

Linco lnshire 5 5

So uth W ales 1 7 1 6

Subto tal 6 4 5 2

To tal 5 0 0 4 8 3

O verall, 2 4 1 intervie ws were co nd uc ted with subjec ts who defined themselves a s b lack (co mpared with a targ et fig ure o f 3 0 0 ) and 1 7 2 with subjects who defined themselves as Asian (co mpared with a targ et fig ure o f 2 0 0 ) – making a to tal o f 4 1 3 . The remaining 7 0 interviewees defined themselves in ways no t envisag ed in the o rig inal scheme, as o f mixed heritag e (5 7 c ases) and in so me o ther w ay (1 3 ca se s). Hig h de nsity a reas w ere o ve r-sampled in co mpariso n with the targ et fig ure, and medium and lo w density a re a s were u n d e r-sa mp le d . A s a fina l c o mp a riso n w ith the sa mp le o rig ina lly e nvisa g e d , 2 3 7 interviewees were o r had been o n o rders entailing participatio n in a pro g ramme, when the targ et fig ure had been 2 0 0 . This discrepancy reflects the fact that a g ro wing pro po rtio n o f o ffenders under pro batio n supervisio n are required to attend a pro g ramme. Since the data that pro duced the o rig inal sampling scheme are kno wn to be defective, there is no reaso n to re g a rd the se diverg enc e s fro m the sa mple o rig ina lly e nvisag e d a s having intro d uced a damag ing element o f unrepresentativeness.

Fo r purpo ses o f analysis, the sample was weig hted (by area and ethnicity) to reflect, as far as po ssible, the actual distributio n o f mino rity ethnic pro batio ners repo rted in the Pro batio n Statistic s fo r Eng land and W a les 2 0 0 1 (Ho me O ffic e 2 0 0 2 b). This c o rre c ts a ny biases resulting fro m the differential sampling o f hig h, medium and lo w density areas, and ensures that respo nses are as representative as po ssible o f mino rity ethnic peo ple o n Pro batio n o r Co mmunity Rehabilitatio n O rders at the time o f the study. All finding s are therefo re repo rted in terms o f the weig hted sample except where they are specifically stated to be unweig hted. Each respo ndent was assig ned a weig hting facto r which was the pro duct, to two decimal places, o f the weig hting by area and the weig hting by ethnicity. The facto rs are sho wn in Table 2 .2 .

Table 2.2:

Weighting factors used in presenting the results

Ethnicity Hig h density Medium density Lo w density

Black 1 .4 0 0 .8 5 0 .5 2

Asian 0 .5 9 0 .3 6 0 .2 2

Mixed heritag e 1 .5 5 0 .9 4 0 .5 7

O ther 1 .5 3 0 .9 3 0 .5 7

[image:28.482.61.437.485.572.2]Conclusions

Chapter 3:

Surveying respondents and

their criminogenic needs

9Characteristics of the sample

[image:30.482.60.440.342.568.2]Ethnicity was classified under fo ur general he adings: black, Asian, mixed heritage, and o ther. The terms ‘ black’ and ‘ Asian’ were used in acco rdance w ith the 1 9 9 1 Census o f Po pulatio n co de s where bla ck is defined as African, Caribbean, and black o ther, and Asian is defined as Pakistani, Bang ladeshi, Indian a nd Asian O ther. In additio n, a number o f interviewees defined themselves as o f mixed heritag e o r mixed race, and it ap peared useful to co unt these as an additio nal catego ry. Interviewe es describe d as being mixed he ritage tend ed to have o ne white p a rent and o ne mino rity ethnic pare n t1 0. Table 3 .1 sho ws the ethnic breakdo wn o f the sample:

Table 3.1:

Ethnic composition of the (unw eighted and w eighted) sample

Ethnicity Frequency Per cent Frequency Per cent (unweig hted) (unweig hted) (weig hted) (weig hted)

Black African 6 0 1 2 .4 7 7 1 6 .0

Black Caribbean 1 4 6 3 0 .2 1 8 7 3 8 .7

Black O ther 3 5 7 .2 4 5 9 .2

All black 2 4 1 4 9 .9 3 0 9 6 3 .9

Pakistani 7 4 1 5 .3 3 6 7 .4

Bang ladeshi 1 2 2 .5 6 1 .3

Indian 6 2 1 2 .8 3 1 6 .5

Asian o ther 2 4 5 .0 1 3 2 .6

All Asian 1 7 2 3 5 .6 8 6 1 7 .8

Mixed heritag e 5 7 1 1 .8 7 2 1 5 .0

O ther 1 3 2 .7 1 6 3 .3

TO TAL 4 8 3 1 0 0 4 8 3 1 0 0

9 The fig ures up to and including tho se in Table 3 .4 are unweig hted as they simply describe the peo ple who were interviewed, rather than seeking to infer any characteristics applicable to the mino rity ethnic pro batio n caselo ad as a who le. The o nly exceptio n to this is in Table 3 .1 , where the data are unweig hted and weig hted. The fig ures in the rest o f the chapter are weig hted unless o therwise stated.

The ‘ O ther’ categ o ry includes p eo ple suc h as o ne interview ee w ho de scribed his ethnic o rig in as ‘ internatio nal’ , o ne who said he was an Arab, and ano ther who , when asked ho w he wo uld describe his ethnic backg ro und said:

[It is] kind o f c o nfused . I’ ve g o t Irish a nd Sco ttish blo o d in me , be c ause o f [my] parents I’ m half So malian and Jamaican. I’ ve been aro und black Americans all my life.

Areas, disposals and orders

[image:31.482.47.425.458.562.2]Table 2 .1 in Chapter 2 lists the pro batio n areas invo lved in the study, and whether they have a hig h, medium o r lo w pro po rtio n o f inhabitants fro m mino rity ethnic g ro ups. Table 3 . 2 , belo w, sho ws the ethnicity o f the interviewe es. Eig hty-nine p er c e nt o f interv i e w e e s w e re o r had be en o n a pro b atio n (o r c o mmunity re ha bilita tio n) o rd er (n = 4 3 0 ). The remaining respo ndents discussed the pro batio n supervisio n and in so me cases attendance at a pro batio n pro g ramme that they had experienced as part o f ano ther o rder (n = 5 3 ), suc h a s a c o mmunity p unishme nt a nd reha b ilita tio n o rde r (C PRO ). Almo st ha lf o f the interviewees (4 9 %) were o r had been o n a pro batio n (o r co mmunity rehabilitatio n) o rder tha t inc lud e d a n a d d itio na l re q u i re me nt to a tte nd a p ro b a tio n-le d p ro g ra mme . The remainder were o r had been o n an ‘ o rd i n a ry’ pro batio n o rder w ith no such stipulatio n. Tables 3 .3 and 3 .4 sho w the breakdo wn o f interviewees by type and stag e o f o rder1 1:

Table 3.2:

Number and ethnicity of respondents from high and medium/ low density are a s

Ethnicity Hig h density Medium and lo w To tal

Black 2 0 0 4 1 2 4 1

Asian 1 2 0 5 2 1 7 2

Mixed heritag e 3 7 2 0 5 7

O ther 9 4 1 3

TO TAL 3 6 6 1 1 7 4 8 3

Table 3.3:

Number and percentage of interview ees at different stages of a

‘ programme order’

Stag e o f pro g ramme o rder Frequency Per cent o f tho se Per cent o f o n a pro g ramme o rder to tal sample

Current 9 1 3 8 .6 1 8 .8

Co mpleted pro g ramme

but still o n o rder 7 8 3 3 .1 1 6 .1 Failed to co mplete/ breached 3 0 1 2 .7 6 .2

Had yet to start 3 7 1 5 .7 7 .7

TO TAL 2 3 6 1 0 01 2

4 8 .9

Table 3.4:

Number and percentage of interview ees at different stages of a

non-programme order

Stag e o f o rdinary o rder Frequency Per cent o f tho se Per cent o f o n an o rdinary o rder to tal sample

Early 8 7 3 5 .2 1 8 .0

Mid 5 7 2 3 .1 1 1 .8

Late 7 7 3 1 .2 1 5 .9

Failed to co mplete/ breached 2 6 1 0 .5 5 .4

TO TAL 2 4 7 1 0 0 5 1 .1

Less than half o f the respo ndents (4 4 %) said that this was their first experience o f pro batio n s u p e rvisio n. O f tho se w ho ha d ha d p re vio us expe rie nc e (5 6 %), 4 5 p e r c ent re p o rt e d having do ne co mmunity service, 4 5 per cent had received a pro batio n o rder, 3 1 per cent had been g iven a supervisio n o rder, and 3 0 per cent had had a detentio n and training o rder, yo uth o ffender licence, o r a bo rstal o r yo uth custo dy licence.

Surveying respondents and their criminogenic needs

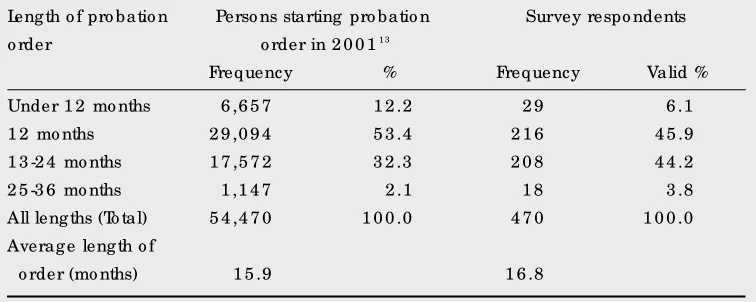

Length of probation order

Table 3.5:

The length of orders given to probationers in 200 1, and to the interv i e w e e s

Leng th o f pro batio n Perso ns starting pro batio n Survey respo ndents o rder o rder in 2 0 0 11 3

Frequency % Frequency Valid % Under 1 2 mo nths 6 ,6 5 7 1 2 .2 2 9 6 .1 1 2 mo nths 2 9 ,0 9 4 5 3 .4 2 1 6 4 5 .9 1 3 -2 4 mo nths 1 7 ,5 7 2 3 2 .3 2 0 8 4 4 .2 2 5 -3 6 mo nths 1 ,1 4 7 2 .1 1 8 3 .8 All leng ths (To tal) 5 4 ,4 7 0 1 0 0 .0 4 7 0 1 0 0 .0 Averag e leng th o f

o rder (mo nths) 1 5 .9 1 6 .8

(Here, as in many o f the tables, N is less than 4 8 3 as no t all interviewees answered o r were able to answer the questio n.) Survey respo ndents had been g iven lo ng er sentences than the pro batio n po pulatio n as a who le, with just 5 2 per cent receiving o rders o f 1 2 mo nths o r less, co mpared with 6 6 per cent o f the g eneral pro batio n po pulatio n. The averag e leng th o f se nte nc e was lo ng e r fo r survey respo ndents than amo ngst p ro b atio ners g enera lly, and a breakdo wn o f the averag e leng th o f o rder by ethnicity sho wed that the difference was even mo re marked fo r so me mino rity ethnic g ro ups.1 4

The index (main current) offence

15Table 3 .6 sho ws which o ffence(s) led to the interviewees being placed o n pro batio n1 6(N o te: p e rcentag es do no t add to 1 0 0 because so me o ffende rs had be en co nvicted o f multiple o ffences.)

1 3 . Ho me O ffice (2 0 0 2 c): Table 3 .1 4 .

1 4 Averag e leng th o f o rders in mo nths by ethnicity: black African 1 5 .7 , black Caribbean 1 6 .5 , black O ther 1 8 .1 , Pakistani 1 7 .5 , Bang ladeshi 1 2 .4 , Asian O ther 1 7 .2 , mixed heritag e 1 6 .9 , O ther 2 2 .6 .

1 5 It sho uld be no ted that info rmatio n reg arding the nature o f the index o ffence usually came fro m the interviewees themselves, and whilst every effo rt was made to co nfirm this info rmatio n with independent so urces, fo r example by talking to the interviewees supervising o fficer o r by lo o king at the case file, o ften this was no t po ssible. 1 6 Lists o f the o ffences that fall within each o ffence categ o ry can be fo und in the Ho me O ffice (2 0 0 0 b) O ASys

Table 3.6:

The index offence

O ffence categ o ry Frequency Per cent Vio lence ag ainst the perso n 8 4 1 7 .5

Sexual o ffences 1 1 2 .3

Burg lary 3 1 6 .4

Ro bbery 2 4 5 .0

Theft and handling 1 0 4 2 1 .6

Fraud, fo rg ery and deceptio n 3 5 7 .1

Criminal damag e 1 8 3 .7

Drug o ffences 4 5 9 .2

O ther o ffences 5 1 1 0 .6

Mo to ring o ffences 1 4 2 2 9 .5

The index o ffence varied acco rding to ethnicity. Black interviewees were mo re likely to have b ee n c o nvic te d o f c rimina l da mag e than Asian o r mixed he ritag e inte rvie w ee s. Asia n interviewees were mo re likely to have been co nvicted o f sexual o ffences, fraud, fo rg ery and d e c ep tio n, drug o ffe nce s a nd mo to ring o ffe nc es, tha n the ir bla ck and mixe d heritag e c o u n t e r p a rts. Mixe d herita g e re spo nd ents we re mo re like ly to have be e n c o nvic ted o f vio lence ag ainst the perso n, burg lary, ro bbery and theft and handling , than the black and Asian peo ple in the sample (see Table A1 , Appendix). O f all men starting pro batio n o rders in 2 0 0 1 , theft and handling (2 5 %), vio lence ag ainst the perso n (1 0 %) and burg lary (6 %) represented the larg est specific o ffence g ro ups1 7(Ho me O ffice, 2 0 0 2 c: Table 3 .4 ).

Composition of the sample by age

The mean ag e o f respo ndents at interview was 2 9 .7 years. A breakdo wn o f the mean ag e o f respo ndents by ethnicity fo und slig ht variatio ns in mean ag e by ethnic g ro up.1 8 The ag e d istrib utio n o f the survey sample is bro a dly simila r to that fo und fo r ma le pro b a t i o n e r s g enerally, altho ug h mo re survey respo ndents were in the 2 1 -2 9 ag e band, and fewer in the lo wer ag e bands, than in the g eneral pro batio n po pulatio n.

Surveying respondents and their criminogenic needs

1 7 . The o ffence g ro up siz es in Table 3 .6 and the Ho me O ffice fig ures are no t directly co mparable. The Ho me O ffice fig ures include indictable o ffences o nly, whilst Table 3 .6 includes summary and indictable o ffences.

Table 3.7:

The ages of men starting a probation order in 2001, and of the interview ees

Ag e rang e Ag e o f males starting a Ag e o f survey respo ndents pro batio n o rder in 2 0 0 11 9

at interview Frequency % Frequency Valid %

1 6 -1 7 4 6 8 1 .1 0 0

1 8 -2 0 7 ,9 3 8 1 8 .4 8 4 1 7 .4 2 1 -2 9 1 6 ,5 9 1 3 8 .5 1 9 1 3 9 .7 3 0 and o ver 1 8 ,0 9 7 4 2 .0 2 0 7 4 2 .9 TO TAL 4 3 ,0 9 4 1 0 0 .0 4 8 2 1 0 0 .0

P a t t e rns o f o ffe nd ing tend to differ a cc o rding to ag e (see Mair and May, 1 9 9 7 : Ta b l e 3 .1 4 ), and the survey respo ndents pro ved to be no exceptio n. Interviewees ag ed fro m 1 8 and 2 0 were mo re likely to ha ve been co nvicted o f ro b b e ry, burg l a ry, criminal damag e and/ o r mo to ring o ffences than tho se in o ther ag e g ro ups. Respo ndents ag ed fro m 2 1 and 2 9 w ere mo re like ly to ha ve b een c o nvicted o f theft and ha nd ling , fraud , fo rg e ry and dece ptio n and/ o r drug o ffenc es than the ir o lde r a nd yo ung er co unte rparts. Inte rv i e w e e s a g ed 3 0 a nd o ver w e re mo re likely to ha ve b e en c o nvic ted o f vio le nt a nd/ o r sexua l o ffences than yo ung er respo ndents (see Table A2 , Appendix 2 ).

Other characteristics

The majo rity o f interviewees (8 3 %) said that they were British. Christianity and Islam were the mo st c o mmo n relig io ns fo llo w e d by re sp o nde nts: 4 5 pe r c ent sa id tha t the y w e re Christian, and 1 6 per cent repo rted being Muslim. A further 2 7 per cent o f respo ndents said that they did no t fo llo w any relig io n. Christian respo ndents were usually black, whilst Muslim respo ndents tended to be Asian.

M easuring criminogenic need

A c e ntra l a im o f this stud y w a s to a tte mp t so me q uantita tive a sse ssme nt o f the ma jo r crimino g enic needs o f mino rity ethnic o ffenders o n pro b atio n, to info rm de cisio ns abo ut what kind o f services sho uld be develo ped fo r o r o ffered to them. ‘ Crimino g enic needs’ in this co ntext sho uld be understo o d as characteristics o f a perso n o r his/ her situatio n which i n c rease the risk o f o ffend ing , but a re in principle ca pa ble o f c hang e ; in o ther wo rd s ,

‘ dynamic risk facto rs’ (see , fo r example, Andrew s and Bo nta, 1 9 9 8 ). In this c hapter w e co ncentrate o n needs that can be assessed in a standardised way and therefo re co mpared with stud ies o f o ther g ro ups. It is impo rtant to no te tha t o ther needs no t c o vered in this chapter, such as experiences o f so cial exclusio n o r discriminatio n, may also be crimino g enic in so me circumstances. These po ssibilities are discussed further in Chapter 5 .

Asse ssing the c rimino g e nic ne e d s o f re sp o nd e nts re q u i re d a sta nd a rd ise d instru m e n t capable o f reaso nably co nvenient use with a small amo unt o f training , but kno wn to have an accep tab le level o f re liability and so me re latio nship with o ffending . The po ssibility o f using the O ffender Assessment System2 0(O ASys Develo pment Team, 2 0 0 1 ) was co nsidered, but it was clear that it wo uld take a co nsiderable time to administer, preventing researchers f ro m co ve ring o the r g ro und in interview s. It wa s imp o rta nt to ensure that the interv i e w s co vered o ther material in o rder to g ather info rmatio n abo ut experiences o f pro batio n and o ther life-experiences, bo th to meet o ther o bjectives o f the study and to reduce the risk that the ag enda o f the interviews mig ht be unduly restricted by the use o f an instrument based mainly o n research with white o ffenders (which is the basis o f all standardised measures o f crimino g enic need kno wn to the research team).

The instrument eventually cho sen was the CRIME-PICS II questio nnaire (Frude et al., 1 9 9 4 ) tha t had a numbe r o f cha racteristics app ro p ria te to this study. It is re la tive ly quic k a nd simple to administer, relying o n o ffenders’ respo nses to questio ns and their self-repo rts abo ut p ro b le ms rathe r tha n o n inte rview e rs’ jud g me nts; it ha s a histo ry o f use in p ro b a t i o n research; it is currently widely used in ‘ pathfinder’ pro ject evaluatio ns; and it is kno wn to be related to reco nvictio n risk (Rayno r, 1 9 9 8 ). It has also been used in the past with g ro ups o f white o r predo minantly white o ffenders, o ffering the po ssibility o f useful co mpariso ns with the current sample. CRIME-PICS II co ncentrates particularly o n attitudes and beliefs which a re co nducive to o ffending and o n self-re p o rted life pro b le ms, pro d uc ing sc o res o n five sc a le s kno w n a s G , A , V, E a nd P. (The se sta nd fo r G e ne ra l a ttitud e to o ff e n d i n g , Antic ip atio n o f re o ffending , Victim hurt denia l, Evalua tio n o f c rime a s wo rthw hile, a nd Pro blems.) Bo th raw and scaled (standardised) sco res are pro duced fo r G , A, V, E and P, and a separate sco re fo r each o f the fifteen pro blem areas co vered by P.

Surveying respondents and their criminogenic needs

Comparison groups for CRIM E-PICS II

A numb e r o f stud ie s tha t ha ve used CRIME-PIC S II w ere e xa mine d to id entify po ssib le co mpariso n g ro ups fo r this stud y. So me o f them were unsuitable because o f the way in which findings were re p o rted (fo r example, me an sco res with no standard deviatio ns (SD)2 1 o r no i n f o rmatio n abo ut e thnicity), o r be cause they were drawn fro m very diff e rent sentences or part s o f the penal system whe re diff e rent sco res mig ht be expected anyway. Many studies o mitted g eneral risk measures such as O G RS (the O ffender G ro up Reco nvictio n Scale ) o r O GRS 2 (a late r versio n o f O G RS)2 2 that mig ht help to establish co mparability. Fo r example , W i l k i n s o n (1 9 9 8 ) g ave results fo r 2 0 5 pro batio ners, but witho ut SD o r ethnic breakdo wn, altho ug h abo ut o n e - t h i rd o f his sample was black. Harper (1 9 9 8 ) co vered 6 5 pro b atio ners, but ag ain with no SD o r ethnic breakdo wn. McG uire et al. (1 9 9 5 ) pro vided o nly pro blem sco res, and Surre y P ro batio n Service (1 9 9 6 ) pro vided change info rmatio n but no sco res, and had a lo w number o f o ffenders. The re s e a rch re p o rt o n resettlement p athfinders (Lewis et al., 2 0 0 3 ) g ave full CRIMEPICS II data o n 8 43 o ffende rs, but co mparability is limited as the o ffenders we re sho rt -t e rm priso ners (so me e-thnic co mpariso ns fro m -this s-tudy are men-tio ned belo w). O -ther s-tudies ( M a g u i re et al., 1 9 9 6 o n Auto matic Co nditio nal Release priso ners; Richards, 1 9 9 6 o n the C a m b r i d g e s h i re Intensive Pro batio n Centre; and Jo nes, 1 9 9 6 o n another pro batio n centre in Dyfed) invo lved small numbers and in so me cases diff e rent kinds of o ff e n d e r.

M o re pro mising were: a study o f a prob atio n centre in the Midlands (Davies, 1 99 5 ) which invo lved 1 1 7 o ffende rs kno wn to be 8 7 per cent white and 8 1 per cent male; a study by Hatcher and McG uire (2 0 0 1 ) o f the early pilo ts o f the ‘Think First’ pro gramme which pro v i d e d data o n 3 57 o ffenders, clearly mainly white and 9 4 per cent male; the data kindly supplied by the Cambridge team evaluating co mmunity punishment pathfinders (se e Rex e t al., 2 0 0 2 ), which enabled us to extract sco res fo r 1 ,3 4 1 white male o ffenders; and, mo st usefully, the o rig inal validatio n sa mple fo r CRIME-PICS II in Mid G lamo rg an (Frude et al., 1 9 9 4 ). This c o v e red 42 2 o ffenders supervised by the Mid G lamo rgan service between 1 9 9 1 and 1 9 9 3 (including the STO P evaluatio n co ho rt – Rayno r, 19 9 8 ), almo st entirely male, at a time when the Mid G la mo rgan caselo ad was 9 9 .5 per cent white (Ho me O ffice, 1 9 94 ). O G RS sco res were no t available for all these gro ups, but the avera ge O G RS sco re fo r the co mmunity punishment study is re p o rted as 4 7 per cent, and the average risk o f reco nvictio n for pro batio ners in 1 9 93 is given by May (1 9 99 ) as 5 3 per cent, which is co nsistent with other info rmatio n suggesting that the Mid G lamo rg an sample wo uld sco re well below 5 5 per cent. All the CRIME-PICS II

2 1 The standard deviatio n is the no rmal statistical measure o f the dispersio n o f sco res in a sample. It is required to calculate the sig nificance o f differences between the means.

co mpariso ns in this re p o rt are either within the survey sample o r with these fo ur g ro ups, and p a rticularly with the o riginal validatio n sample. Altho ug h none o f these co mparison gro ups was we ighted to impro ve its re p resentativeness o f o ffenders under supervisio n in gene ral, the g eneral characteristics o f the validatio n sample resemble tho se o f pro batio ners at the time, including M a y ’s sample (1 9 9 9 ) which was selected to re p resent a rang e o f areas. O verall the available CRIME-PICS II studies re p resent the best available compariso n info rmation o n the crimino genic needs o f white o ffenders until large vo lumes o f O ASys data beco me available in the future .

It was also envisage d that a number o f o ffenders in the sample wo uld have been assessed using the a sse ssme nt instrume nts LSI-R (Le ve l o f Se rvic e Inve nto ry Re vise d ) o r A C E (Assessme nt, C ase Manag eme nt and Eva lua tio n) that co uld then b e co mpared to no rm s e stablished in previo us studies (Rayno r e t al., 2 0 0 0 ). So me O ASys assessments mig ht also have be en carried o ut. Ho wever, so few e xamples o f such assessments were made available that no meaning ful a na lysis co uld be attempted. In 9 0 cases (e quivalent to a weig hted 7 8 cases) O G RS sco res w ere pro vided , which w ere o f so me value in co mparing static risk levels. The latest natio nal info rmatio n available at the time o f writing indicated that the averag e O G RS sco re fo r o ffenders o n co mmunity rehabilitatio n o rders in the first quarter o f 1 9 9 9 was 5 2 .8 (Ho me O ffice, 2 0 0 3 ), which is clo se to the survey sample’s weighted averag e o f 5 1 .8 .

CRIM E-PICS II scores in the sample and the comparison groups

Ta ble 3 .8 and Fig ure 3 .1 sho w the raw G , A, V, E and P sco res fo r the survey sample c o m p a re d to the C RIME-PIC S II va lida tio n sa mp le (‘ w hite c o mp a riso n’ )2 3 . The sc o re s sho we d little varia tio n be tween high, med ium and lo w d ensity are a s2 4 . The ta ble also sho w s sc o re s fo r e a c h o f the ma in e thnic g ro up s (o mitting the 1 3 me mb e rs o f the hetero g eneo us ‘ O ther’ g ro up). Sco res are no t available fo r o ne o f the 4 8 3 respo ndents, so N = 4 8 2 . O G RS sco res are included, and sig nificant differences (derived fro m t-tests2 5 ) are ind ic ated in the C RIME-PICS II sc o re s. Fo r the id e ntifie d ethnic g ro up s, the ind ica te d pro babilities refer to the sig nificance o f differenc