Incident Management in outsourcing

Alfredo Ramiro Reyes Zúñiga

Submission date:

December 2014

Responsible professor:

Colin Boyd, ITEM

Supervisor:

Maria B. Line, ITEM

Norwegian University of Science and Technology

Department of Telematics

Abstract

The current ICT environment is becoming progressively contracted out to third parties. Outsourcing ICT services has created alternative attack surfaces. Therefore, effective strategies to conduct incident man-agement in outsourcing settings are needed. Few published standards and guidelines addressed outsourced ICT services and what is required to conduct efficient incident management in these settings. Moreover, there is not much published literature about current practices. In this project, an empirical study was conducted on Incident management practices in outsourcing settings. The research was conducted as a case study performing a qualitative study of three Norwegian organizations, one ex-pert and a survey. The findings revealed a lack of systematic approaches. Finally, this research contributes with a framework of published and forth-coming ISO/IEC standards to provide guidance on incident management in outsourcing settings. This research provides also with recommenda-tions and a set of quesrecommenda-tions to prepare for the challenges involved in the aforementioned settings.

Contents

List of Figures ix

List of Tables xi

List of Acronyms xiii

1 Introduction 1 1.1 Objectives . . . 2 1.2 Outline . . . 2 2 Method 5 2.1 Qualitative research . . . 5 2.2 Choice of method . . . 5 2.3 Case study . . . 6 2.4 Qualitative interviews . . . 7 2.5 Document study . . . 8

2.6 Qualitative data analysis . . . 8

2.7 Participants . . . 9

2.8 Ethical considerations . . . 9

2.9 Challenges . . . 10

3 Background study 13 3.1 Related Work . . . 13

3.2 Standards and guidelines . . . 15

3.2.1 ISO/IEC 27001:2013 – Information security management . . 15

3.2.2 ISO/IEC 27002:2013 Code of practice for information security controls . . . 16

3.2.3 ISO/IEC 27035:2011 Information security incident management 17 3.2.4 ISO/IEC 27036-*:2013+ Information security for supplier rela-tionships . . . 19

3.2.5 NIST Special Publication 800-61 . . . 20

3.2.6 ENISA – Good Practice Guide for Incident Management . . . 20

3.3 Forthcoming standards . . . 21 v

3.3.1 ISO/IEC 19086-* Service Level Agreement (SLA) framework

and Technology . . . 22

3.3.2 ISO/IEC 27017 Code of practice for information security con-trols based on ISO/IEC 27002 for cloud services . . . 22

3.3.3 ISO/IEC 27035-* Information security incident management 22 3.3.4 ISO/IEC 27036-4: Guidelines for security of cloud services . . 23

3.4 Framework of standards relationships . . . 23

3.5 European ongoing developments . . . 24

3.5.1 European Cloud Computing Strategy . . . 25

3.5.2 Cybersecurity Strategy . . . 26

3.5.3 The Cloud Accountability Project (A4Cloud) . . . 26

3.6 Incident management models . . . 27

4 Case Introductions 29 4.1 Case A . . . 29 4.2 Case B . . . 30 4.3 Case C . . . 30 4.4 Expert 1 . . . 31 4.5 Survey . . . 31 5 Findings 33 5.1 Case A . . . 33

5.1.1 Plan and Prepare . . . 33

5.1.2 Detection and Reporting . . . 35

5.1.3 Assessment and Decision . . . 36

5.1.4 Responses . . . 36

5.2 Case B . . . 38

5.2.1 Plan and Prepare . . . 38

5.2.2 Detection and Reporting . . . 39

5.2.3 Assessment and Decision . . . 40

5.2.4 Responses . . . 41

5.2.5 Lessons learnt . . . 41

5.3 Case C . . . 42

5.3.1 Plan and Prepare . . . 42

5.3.2 Detection and Reporting . . . 42

5.3.3 Responses . . . 42

5.4 Expert 1 . . . 43

5.4.1 Plan and Prepare . . . 43

5.4.2 Detection and Reporting . . . 44

5.4.3 Assessment and Decision . . . 45

5.4.4 Responses . . . 45

5.5 Survey . . . 49

6 Discussion 55

6.1 The research questions revisited . . . 55 6.1.1 How different organizations perform incident management

when third party companies are involved? . . . 55 6.1.2 How are the responsibilities distributed? . . . 56 6.1.3 What are the challenges that organizations experience during

the operational phases of incident management in the out-sourced setting and how could they be addressed? . . . 57

7 Conclusions 63 References 65 A Information Letter 69 B Interview guide 71 C Survey 73 D Poster 79

List of Figures

2.1 Different Research Methods, modified from [Yin14] . . . 7

3.1 Incident Management Phases . . . 18

3.2 Incident Response Lifecycle, modified from [NIS12] . . . 21

3.3 Incident Management and Incident Handling, adapted from [MRS10] . . 21

3.4 Framework of published and forthcoming standards . . . 24

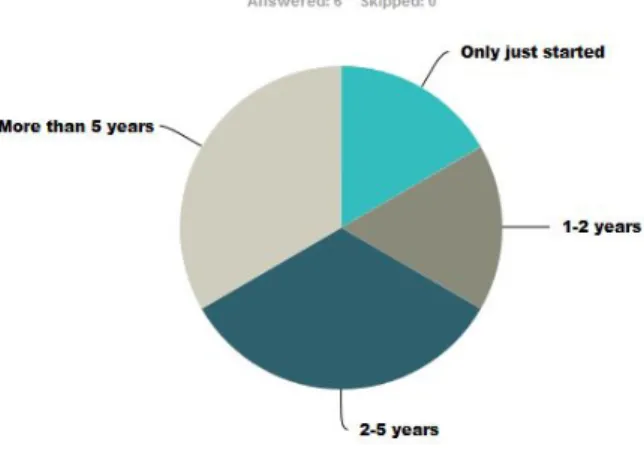

5.1 Participants experience with incident management activities. . . 49

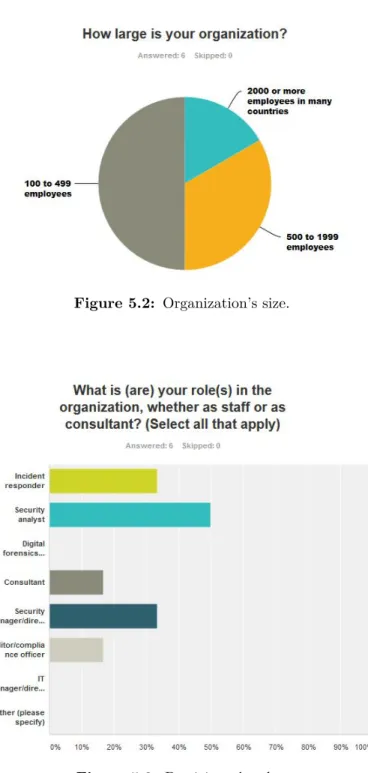

5.2 Organization’s size. . . 50

5.3 Participant’s roles. . . 50

5.4 Participant’s industry sectors. . . 51

5.5 Challenges when managing incidents involving third parties. . . 52

5.6 Organization’s approaches to deal with incident management in outsourc-ing scenarios. . . 53

5.7 Amount of incidents in an outsourcing setting managed by the partici-pant’s organizations. . . 53

5.8 Effectiveness of the participant’s incident management team dealing with outsourcing settings. . . 54

5.9 Roles and responsibilities defined in the incident management plan re-garding third parties. . . 54

A.1 Information letter provided to the case study participants . . . 70

B.1 Questionnaire guide used during the interviews . . . 72

C.1 Survey questions. Part 1 . . . 74

C.2 Survey questions. Part 2 . . . 75

C.3 Survey questions. Part 3 . . . 76

C.4 Survey questions. Part 4 . . . 77

D.1 Research poster presented at the NordSec 2014 conference . . . 80

List of Tables

3.1 Incident management models . . . 27

4.1 Incident management models in Case A. . . 29

4.2 Incident management model in Case B. . . 30

4.3 Incident management model in Case C. . . 30

4.4 Incident management models where Expert 1 is involved. . . 31

List of Acronyms

CERTComputer Emergency Response Team CISOChief Information Security Officer

CSIRTComputer Security Incident Response Team

ENISAEuropean Network and Information Security Agency FIRSTForum of Incident Response and Security Teams ICTInformation and Communication Technology IDSIntrusion Detection System

IECInternational Electro-technical Commission IRCInternet Relay Chat

IRTIncident Response Team

ISIRTInformation Security Incident Response Team ISMSInformation Security Management System ISOInternational Organization for Standardization ISPInternet Service Provider

ITInformation Technology

MSSPManaged Security Service Provider

NISTNational Institute for Standards and Technology RAMRandom Access Memory

SLAService Level Agreement SLOService Level Objectives VPNVirtual Private Network

Chapter

1

Introduction

The current Information and Communication Technology (ICT) environment is becoming progressively contracted out to third parties. It is rare to find nowadays an organization that is not outsourcing at least partially its ICT operations. A rising number of companies provide specific ICT services to help organizations to focus on their core business and mitigate the lack of expertise to accomplish specific functions.

Several organizations outsource their ICT services to a professional ICT supplier. Outsourcing has several advantages, both for small and large organizations. But it also has pitfalls. It poses new challenges, responsibilities and requires communication improvements between two or even more separate organizations.

However, outsourcing ICT operations has created new venues for attacks. The 2014 report regarding cyber-attacks against energy suppliers [Res14], states that in order to reach large organizations, the attackers targeted their suppliers with less security. Such type of attacks have had a global presence already.

Regarding the recent cyber-attacks to the oil and energy companies in Norway, Alan Calder, founder and executive chairman of IT Governance1, responded to the

news on an interview to the digital magazine SCMagazineUK2 declaring:

“Spear phishing attacks – increasingly through the compromised sys-tems of small suppliers to large companies – is an increasingly interesting attack vector for criminals attempting to steal valuable information”

Incident management requires comprehensive qualification, training, and especially planning. And if, or when, an information security incident occurs, it needs to be

1IT Governance website http://www.itgovernance.co.uk/

2

http://www.scmagazineuk.com/hundreds-of-norwegian-energy-companies-hit-by-cyber-attacks/article/368539/

2 1. INTRODUCTION

efficiently and appropriately responded to. This is not the time for clarifying responsibilities.

Even though companies and organizations might be prepared for dealing with incidents in their ICT systems, studies have revealed that third party companies are not adequately involved in planning for incidents [TLJ14], despite the fact that in many cases the resolution depends on the supplier collaboration during the incident management.

This topic requires further investigations to identify whether there are specific challenges related to incident management in outsourcing settings. If that is the case, then it is relevant to identify: Which are these challenges? Why do these challenges arise and how could they be addressed? Current standards and recommendations have a lack of information to address outsourcing. Investigations are needed to consider more specific or different kinds of recommendations when it comes to incident management in outsourcing.

1.1

Objectives

This research project aims to identify current practices and successful strategies for practicing incident management in an outsourced setting. It is hoped that this study will develop new understandings about improvements needed to overcome challenges related to incident management in the aforementioned settings. The research questions are:

– How do different organizations perform incident management when third party companies are involved?

– How are the responsibilities distributed?

– What are the challenges that organizations experience during the operational phases of incident management in an outsourced setting?

– How potential challenges related to incident management in an outsourcing setting could be addressed?

1.2

Outline

Chapter 2 (Research method) describes what qualitative research involves, the process of selection for the research method and the case study process followed in the present study. An incident management background study is presented on Chapter 3 (Background study), where related published standards, guidelines and forthcoming standards are described and analyzed and a current standard’s framework

1.2. OUTLINE 3

for incident management in outsourcing settings is depicted. Furthermore a brief description on European ongoing developments on the topic is introduced. In Chapter 4 (Case Introductions) the organizations and experts in the case study are described. The findings from the case study are detailed in Chapter 5 (Findings). Chapter 6 (Discussion) discusses the findings described in chapter 5 and compares them with the background study presented in chapter 3. In Chapter 7 (Conclusions), conclusions and future work are described.

Appendix A contains the information sheet provided to the case study participants. In Appendix B the Interview guide can be found. Appendix C includes the survey provided to professionals on the field. Finally, the research poster presented at the NordSec 2014 conference is presented in Appendix D.

Chapter

2

Method

The study aims to extract in-depth information on how incident management is performed in practice when outsourcing scenarios are present.

2.1

Qualitative research

Qualitative research involves exploring specific topics or issues, understanding phenom-ena and finding answers to questions, by analyzing and making sense of unstructured data, through different research methods. It originated in the social and behavioral sciences. However, today is a method of inquiry employed in many disciplines.

Some qualitative research typical features [Rob11] are described as :

– Accounts and findings are presented verbally or in other non-numerical form. There is little or no use of numerical data or statistical analysis.

– Contexts are seeing as important. There is a need to understand phenomena in their setting.

– Situations are described from the perspective of those involved. – The design of the research is flexible throughout the whole process. – The generalizability of findings is not a major concern.

– It takes place in natural settings.

– It is usually small-scale in terms of numbers of persons or situations researched.

2.2

Choice of method

Different research methods have particular advantages and disadvantages, three criteria to consider are: type of research question posed, requirement of control 5

6 2. METHOD

over behavioral events and the focus on current phenomena contrary to historical phenomena.

To choose among the various research methods, the first and most important condition is to distinguish the kind of research question being posed. Then, the next condition is to determine whether control of behavioral events is needed and finally make a decision on contemporary events versus historical events.

The defined question for this study, is a “how” question. As stated in section 1.1 Objectives, the study aims to identify current practices and successful strategies, where there is no control over events. The study focus on contemporary phenomenon, even though some recent past events are considered, such as ICT incidents, the main objective is on current practices.

Based on this, case study emerged as the most suitable method for this study. Case studies are a preferred method when:

– “How” and “why” questions are posed. – Little or none control over events prevails

– Focus is on a current phenomenon within a real life context.

2.3

Case study

Yin describes a case study as “an empirical inquiry that investigates a contemporary phenomenon in depth and within its real-life context. Furthermore, he specifies that a case study copes with the technically distinctive situation in which there will be many more variables of interest than data points. It relies on multiple sources of evidence, and benefits from the prior development of theoretical propositions to guide data collection and analysis.”[Yin14]

A case study is a linear but iterative process that includes 6 phases: plan, design, prepare, collect, analyze and share.

The Plan phase involves the identification of the research questions and selecting the case study as the choice of research method.

The Design phase addresses the creation of a hypothesis about what is being studied and what is to be learned, as well as propositions that direct the attention to something that should be examined within the scope of study. The design phase purpose is to help to avoid the situation in which the evidence does not address the initial research questions. Here, the logic associating the collected data to

2.4. QUALITATIVE INTERVIEWS 7

Figure 2.1: Different Research Methods, modified from [Yin14]

the propositions as well as the criteria for interpreting the findings, are important components.

The Preparation phase involves creating a protocol for the research, sharpening the researcher skills, training for a particular case study, examining and selecting candidate cases and executing a pilot case study. All of the activities are a preparation for the data collection.

The Collection phase makes emphasis in the use of multiple sources of evidence, coming from at least two different sources and providing similar discoveries. Findings are likely to be more precise and convincing if the conclusions are led by corroboration. Yin defines the interview in as “one of the most important sources of case study information because they can provide essential insights into behavior events.”

The Analysis phase consists of analyzing the data either using a general strategy or by reshaping the data in an exploratory sense in order to develop a systematic identification of what is worth analyzing and how it should be analyzed, to draw empirically based conclusions.

The Share phase involves preparing the case study report, to present the results and findings.

2.4

Qualitative interviews

Myers et al., describe a qualitative interview as one of the most important data gathering tools in qualitative research [MN07]. This description has been comple-mented adding that it is a powerful and flexible tool which purpose is to describe and clarify the people’s experiences [SA11]. There are various types of qualitative

8 2. METHOD

interviews. However, the ones used for this project are referred as Unstructured or semi-structured interview and Structured interview[MN07].

A semi-structured interview is a sketch. The researcher may prepare some questions in advanced, but some improvisation is performed during the interview. An interview guide was used as the incomplete script addressing the main research questions. It can be found in Appendix B.

These type of interviews were performed either face-to-face or via Skype, during a short period of time and voice recorded. Interviews via the application Skype were performed only with participants that were located abroad. The questions during the interviews (face-to-face and via Skype) did not follow any predefined order to enable a fluid conversation and asking for elaborations when needed.

A structure interview contains a complete script prepared in advance and with no room for spontaneity. A survey is an example of this type of interview. A survey was performed with the participation of people with different roles in incident management teams, from a diverse set of organizations, during a course at one of the security conferences in Norway. The survey can be found in Appendix C

2.5

Document study

Relevant published standards, guidelines, forthcoming standards and academic litera-ture was studied to complement the knowledge obtained from the interviews and the survey. This was a key factor to identify a broad overview of scenarios for incident management in outsourcing settings.

2.6

Qualitative data analysis

A qualitative and inductive research method was used on this project. Different categories in the data were identified, as well as patterns and relationships, using a “general inductive approach”, as described by Thomas [Tho06].

He describes a methodical strategy to analyze qualitative data that can produce valid and reliable findings from focused research questions. The primary purpose of this approach is to allow findings to be exposed from the raw data regardless of the research questions and method used.

Thomas listed the purposes of an inductive analysis approach [Tho06], these are: – To digest and summarize raw text data into a brief format.

2.7. PARTICIPANTS 9

– To define clear links between the summary findings derived from the raw data and the research objectives.

– To develop a framework based on the experiences or processes revealed by the raw data.

A digest and summary of data of each individual case is fulfilled in Chapter 5 (Findings). The findings where then linked to the research objectives and a model underlying the experiences or processed derived from the raw data are fulfilled in Chapter 6 (Discussion).

The process of analysis and interpretation from raw data to main findings and conclusions was done following the phases of thematic coding analysis described by Robson [Rob11]. The phases can be outlined as follows:

1. Getting familiar with the data 2. Generating initial codes. 3. Identifying themes.

4. Constructing thematic networks.

5. Comparing and interpreting the patterns.

2.7

Participants

The participating organizations in this study are all Norwegian organizations. The organizations were selected according to their involvement with outsourcing scenarios. The participant further described as Expert 1 was selected due to his expertise and also due to his experience in different scenarios of incident management in outsourcing settings. This participant, as well as all the participants that took part in the survey, are Norwegian citizens.

The core activities from the participating organizations and all participants belong to different sectors which could lead to interesting findings. Sectors and expertise are described in chapter 4.

2.8

Ethical considerations

The purpose of the research was informed to the participants when the interview was requested. Simultaneously an informed consent form was provided to them to ask for their consent. The form described what the participation in the project implied, and

10 2. METHOD

what will happen to their personal information, since the interviews were recorded. A voluntary participation was clearly stated with the option to withdraw at any time. The anonymity and privacy of those who participated in this project was respected. Anonymity is provided to the participants and their organizations on this report to prevent their personal information and information security practices becoming pub-lic. All information that could directly or indirectly identify individuals or individual organizations or even link them was anonymized or deleted. Participating organiza-tions are referred on the report using alias names. No individuals or organizaorganiza-tions are recognizable in this report. At the end of the project research all recordings were securely erased.

This project was reported to the Norwegian Social Science Data services. The information sheet provided to the case study participants can be found in Appendix A.

2.9

Challenges

A small number of organizations are studied and a small number of participants were involved due to time restrictions. The author had little or no experience in preparing and conducting qualitative interviews. The data collection process was based on interviews and a survey, the challenges with each approach should be considered.

Challenges with the interviews:

– Ambiguity of language can create confusion on the objectives of the research during the request for interviews.

– Requesting for interviews in a short time basis creates difficulties to get them. – The participants may have chosen not to share important information for the research derived from a lack of trust. This could lead to an incomplete data gathering.

– Limited time for the interviews could have caused limited answers, which are prone to leave out relevant information.

– Posing “why” questions during the interview could create defensiveness on the interviewee.

2.9. CHALLENGES 11

– Conducting a survey on-line might influence the number of participants that answered it.

– Finding an information security event where the participants invited to partici-pate in the survey would be all related to incident management tasks.

– Motivating the participants to fill out the survey.

– The participants may have chosen not to share important information for the research derived from a lack of trust.

– Ambiguity of language can create confusing questions.

Chapter

3

Background study

This chapter introduces relevant background information with regard to incident man-agement in outsourcing settings. An overview of relevant published and forthcoming standards, guidelines as well as related European ongoing research is presented.

3.1

Related Work

Incident management is a term that defines all the activities related to managing information security incidents. It outlines the sequence of acts required to prepare for, detect, analyze, restore, and prevent future incidents.

Incident management is not only about handling an incident. It includes activities for the entire set of tasks involved with the incident response lifecycle, from planning to learning from the experience of dealing with incidents.

Various standards and guidelines addressed incident management. The ones that are well known among the information security community are: ISO/IEC1 27035,

NIST SP2800-61 and ENISA3 Good Practice Guide for Incident Management. All

of them will be described in section 3.2

Outsourcing is often perceived as the process that takes place when a company contracts out a business function to a third party. This process involves a contractual agreement.

Siepmann presents four types of outsourcing: technology outsourcing, business process outsourcing, business transformation outsourcing and knowledge process outsourcing[Sie13]. Today the first two are predominant.

1International Organization for Standardization/International Electro-technical Commission 2National Institute for Standards and Technology Special Publication

3European Network and Information Security Agency

14 3. BACKGROUND STUDY

Technology outsourcing facilitates the use of technical capabilities from a third party to benefit a company acquiring the services. Business process outsourcing empowers company’s functions that are commonly out of the core company’s compe-tency. This eliminates the need to invest on improving business functions that are not aligned with the company interests.

Abundant academic literature related to incident management can be found. This is a result of the increasing interest on the topic. However, the amount of available literature where the incident management in outsourcing environments is addressed is very limited.

Sherwood [She97] presented an analysis of the main issues concerning security of information in outsourced services, where he looks at the strategy that should be followed to manage information security in this environment.

Siepmann [Sie13] provides comments regarding what should be addressed before outsourcing the ICT services. His comment’s categories are aligned with ISO/IEC 27002. There, few thoughts regarding management of information security events in outsourcing settings can be found.

A literature review on current practices and experiences with incident management was done by Tøndel et al. [TLJ14]. There, the practice of incident management in outsourcing scenarios was identified as one of the incident management challenges in this review. According to their study, additional support and domain specific guidelines on this topic are needed.

Hove et al. [HTLB14] described that incident management in outsourcing settings is a current challenge for incident management and it has not been researched.

The current scenario of incident management is changing rapidly. Through the process of studying the related work and identifying the standards and guidelines (published and working drafts) presented in this chapter, the need to study the

incident management in outsourcing settings became evident.

As described by Hove et al. [HTLB14] and Tøndel et al. [TLJ14] there is a need for research around the topic of incident management in outsourcing settings since it is one of the present incident management challenges. The current available literature does not address it. Sherwood’s analysis [She97], on security of information in outsourced services, lacks an evaluation on incident management. Siepmann’s work [Sie13] addresses risk and security in outsourcing settings, but it has a broader scope, it does not focus on incident management.

3.2. STANDARDS AND GUIDELINES 15

Furthermore, there is no analysis on the challenges at each one of the incident management phases posed by outsourcing ICT services.

3.2

Standards and guidelines

This section presents relevant published standards containing information regarding incident management in outsourcing settings.

3.2.1

ISO/IEC 27001:2013 – Information security management

ISO/IEC 27001:2013 [ISO13a] provides requirements for establishing, implementing, maintaining and continually improving an Information Security Management System (ISMS). An ISMS is a systematic approach to managing sensitive company information so that it remains secure. It includes people, processes and Information Technology (IT) systems by applying a risk management process. The 2013 version is an evolution from the 2005 version, most of the standard content remains without changes. Some differences from the 2005 standard include: more emphasis on measurement and evaluation on organization’s ISMS performance. It also includes a new section on outsourcing.

This section describes some controls from the ISO 27001 standard. The content is, unless specified otherwise, derived from [ISO13a] . The controls, listed on the Annex A from the standard, relevant to the case study are:

– A.15 Supplier relationships.

◦ A.15.1 Information security in supplier relationships.

Objective: To ensure protection of the organization’s assets that is acces-sible by suppliers.

∗ A.15.1.1 Information security policy for supplier relationships. ∗ A.15.1.2. Addressing security within supplier agreements.

∗ A.15.1.3 Information and communication technology supply chain. ◦ A.15.2 Supplier service delivery management

Objective: To maintain an agreed level of information security and service delivery in line with supplier agreements.

∗ A.15.2.1 Monitoring and review of supplier services ∗ A.15.2.2 Managing changes to supplier services – A.16 Information security incident management

16 3. BACKGROUND STUDY

◦ A.16.1 Management of information security incidents and improvements Objective: To ensure a consistent and effective approach to the man-agement of information security incidents, including communication on security events and weaknesses.

∗ A.16.1.1 Responsibilities and procedures ∗ A.16.1.2 Reporting information security events ∗ A.16.1.3 Reposting information security weaknesses

∗ A.16.1.4 Assessment of and decision on information security events ∗ A.16.1.5 Response to information security incidents

∗ A.16.1.6 Learning from information security incidents ∗ A.16.1.7 Collection of evidence

3.2.2

ISO/IEC 27002:2013 Code of practice for information

security controls

ISO/IEC 27002:2013 is a code of practice that provides good practices on information security management. The standard is designed for organizations to use as a reference for selecting controls within the process of implementing an ISMS. [ISO13b]

This section describes some implementation guidance recommendations from the ISO 27002:2013. The content is, unless specified otherwise, derived from [ISO13b]. Here are some implementation guidance recommendations relevant to the case study:

– A.15 Supplier relationships.

◦ A.15.1 Information security in supplier relationships.

There should be processes, procedures, controls, awareness, etc. to mitigate the risks associated with organization’s assets accessible to third parties such as ICT outsourcers and suppliers. This should be implemented in order to protect the organization’s information from end to end through the supply chain (including cloud computing services). It should be agreed within the agreements and contracts.

◦ A.15.2 Supplier service delivery management

Organizations should monitor, review and audit supplier service delivery to maintain an agreed level of information security in line with supplier’s contracts and agreements. All service changes should be managed. – A.16 Information security incident management

◦ A.16.1 Management of information security incidents and improvements There should be a quick, effective and orderly approach to the management

3.2. STANDARDS AND GUIDELINES 17

of information security incidents. It should include responsibilities and procedures to manage (plan, monitor, detect, analyze, report, handle forensic evidence, perform assessment, respond and reuse the knowledge gained from) information security events, incidents and weaknesses.

3.2.3

ISO/IEC 27035:2011 Information security incident

management

ISO/IEC 27035:2011 provides guidance on information security incident management for large and medium-sized organizations. Here is an introduction to the ISO 27035:2011 standard and the content, unless specified otherwise, is derived from [ISO11] .

The standard provides an extensive and structured approach to incident manage-ment, especially to:

– Detect, report and assess information security incidents; – Respond to an manage information security incidents;

– Detect, asses and manage information security vulnerabilities; and

– Continuously improve information security and incident management as a result of managing information security incidents and vulnerabilities.

Incident management consists of five phases (see Figure 3.1): – Plan and prepare

– Detection and reporting – Assessment and decision – Responses

– Lessons learnt

Plan and prepare This phase involves everything that is needed to operate successfully the incident management. An incident management policy should be formulated and documented by each organization and gain commitment from the senior management. Security and risk management policies should be updated and reviewed regularly

A detailed incident management scheme should be defined and documented. The scheme should include:

18 3. BACKGROUND STUDY

Figure 3.1: Incident Management Phases

– A classification scale to grade incidents – Incident forms

– Procedures to the use of the forms

– Operating procedures for the Information Security Incident Response Team (ISIRT)

– Overall plan to establish the ISIRT

– An activity to establish and preserve relationships and connections with internal and external organizations

– Implementation and operation of technical and other support mechanisms – Information security awareness and training program

– Exercises to test the scheme

Once this phase is completed, organizations are ready to manage information security incidents.

Detection and reporting This phase involves detecting, collecting and reporting occurrences of events and vulnerabilities by human or automatic means. The orga-nization should ensure that the right personnel deal with reported vulnerabilities. Information on vulnerabilities, incidents and their resolution should be preserved in a database managed by the ISIRT.

3.2. STANDARDS AND GUIDELINES 19

Organizations should implement monitoring mechanisms to detect and report events, incidents and vulnerabilities. All electronic evidence should be properly logged, gathered and stored securely. All the information collected and reported during this phase should be as complete as possible to ensure that this information collection can be used as a basis for making assessments and decisions.

Assessment and decision This phase involves the assessment of information related to events and decisions to make decisions on whether an event is an incident or not. Organizations should conduct assessments to determine if an event is an incident or a false alarm and determine its impact on assets, information, processes, infrastructure, core services, and others. The assessments should be verified by the ISIRT to confirm the results. This should be followed by decisions on how to deal with the incident, by whom and in what priority. All the information regarding an event, incident or vulnerability should be stored in a database operated and maintained by the ISIRT. Once an event has been detected and reported, the responsibilities should be allocated and the procedures for each notified person should be distributed. Responses This phase involves the making of responses to incidents according to the actions agreed in the preceding phase. The ISIRT should determine if the incident is under control and then assign internal resources and identify external resources that can provide appropriate actions. In some cases, escalation to crisis handling might be necessary. Once the responses have been agreed, every action conducted should be logged and thorough documentation should be created. This would be used to evaluate the effectiveness and efficiency of the incident response process. After handling the incident the case should be closed and recorded in the database managed by the ISIRT.

Lessons learnt This phase follows once an incident has been closed. It involves an analysis on the actions taken and learning from them. Organizations should review the effectiveness of the processes, procedures, and reporting formats in order to make improvements to the incident management scheme and its documentation. Improvements should be made also to the risk assessments. Sharing results within a trusted community is encouraged.

3.2.4

ISO/IEC 27036-*:2013+ Information security for supplier

relationships

ISO/IEC 27036:2013+ is a multipart security guideline for supplier relationships including the relationship management aspects of cloud computing. Here is an introduction to the ISO 27036 standard parts 1, 2 and 3, the content is, unless specified otherwise, derived from [ISO14a] [ISO14b] [ISO13c].

20 3. BACKGROUND STUDY

The standard provides an overview of the guidance intended to assist organizations on the evaluation and treatment of the information security risks that concern the procurement of goods, services and works from an outside external source (suppliers). It provides guidelines to acquirers and suppliers for managing information security risks associated with the ICT products and services supply chain. It also addresses information security risks such as protection of third party information assets, shared responsibilities, coordination between supplier and acquirer to adapt or respond to new and changed information security requirements.

3.2.5

NIST Special Publication 800-61

This standard [NIS12] provides guidance on how to establish effective incident response capabilities. It include guidelines on building capabilities such as creating an incident response plan, developing a policy and procedures for incident handling and reporting, building a team structure, selecting a staff model and planning staff training. It also provides guidance on the Computer Security Incident Response Team (CSIRT) interaction with external parties such as vendors, other CSIRTs, Internet Service Providers, customers, media and law enforcement agencies.

The primary focus of the standard relies on the incident response life cycle which major phases are (see Figure 3.2):

– Preparation

– Detection and Analysis

– Containment, Eradication and Recovery – Post-Incident Activity

3.2.6

ENISA – Good Practice Guide for Incident Management

The guide [MRS10] provides good practices for security incident management. It describes the creation of a Computer Emergency Response Team (CERT), its mission, constituency, responsibility and the type of services that can deliver. It provides information on roles, workflows and policies to deliver a successful incident handling service. It discusses cooperation with external parties and how to get and keep the management involved as success factors.

This guide makes emphasis on incident handling and describes the incident handling process, which involves four components (see Figure 3.3):

3.3. FORTHCOMING STANDARDS 21

Figure 3.2: Incident Response Lifecycle, modified from [NIS12]

Figure 3.3: Incident Management and Incident Handling, adapted from [MRS10]

– Triage – Analysis

– Incident response

3.3

Forthcoming standards

This section presents relevant forthcoming standards containing information regarding incident management in outsourcing settings.

22 3. BACKGROUND STUDY

3.3.1

ISO/IEC 19086-* Service Level Agreement (SLA)

framework and Technology

This is a multipart standard that will provide an overview of Service Level Agreements for cloud services. The current drafts [ISOa] [ISOb] [ISOc] address SLA concepts and requirements to build SLA’s. It aims to establish common building blocks that can be used to create SLA’s facilitating a common understanding between the Cloud Service Providers and their customers. The drafts also specify metrics commonly used in SLA’s for cloud services.

3.3.2

ISO/IEC 27017 Code of practice for information security

controls based on ISO/IEC 27002 for cloud services

This standard will provide directions on the information security elements of cloud computing, for cloud service providers and its customers. The current draft [ISOd] describe on information security roles and responsibilities the importance of the proper definition and documentation of the demarcation of responsibilities of cloud service customer, cloud service supplier and its suppliers as well as the review and confirmation of this responsibilities by the customer.

The working draft describes the issues with ambiguous information security roles and responsibilities. The content is derived from [ISOd]: Ambiguity in the definition of responsibilities related to issues such as data ownership, access control and infrastructure maintenance, may give rise to business or legal disputes, especially when dealing with third parties.

3.3.3

ISO/IEC 27035-* Information security incident

management

The standard ISO/IEC 20735:2011 is currently being revised and extended. It will be divided into three parts:

– ISO/IEC 27035-1 Information security incident management – Part 1: Principles of incident management The current draft outlines basic concepts and phases of information security incident management. The following description is derived from [ISOe]:

The five phases of incident management are:

◦ Plan and prepare: Establish all that is required to operate adequately information security incident management, such as establish incident management policy, establishing an Incident Response Team, etc. ◦ Detection and reporting: Spot and report information security events that

3.4. FRAMEWORK OF STANDARDS RELATIONSHIPS 23

◦ Assessment and decision: Evaluate and determining if it is genuinely an information security incident.

◦ Responses: Forensic analysis, contain, eradicate, recovery and further forensic analysis, where appropriate.

◦ Lessons learnt: Improve the incident management scheme, information security, and risk assessment as a consequence of the experience obtained. – ISO/IEC 27035-2 Information security incident management – Part 2: Guide-lines to plan and prepare for incident response The current draft [ISOf] intro-duces the concepts to plan and prepare for incident management capabilities. It covers recommended requirements to be adopted by organizations in order to respond appropriately to information security incidents.

– ISO/IEC 27035-3: Information security incident management – Part 2: Guide-lines for incident response operations. The current draft [ISOg] offers directions on managing and responding competently to incidents. It also covers Incident Response Team’s organization, formation, operation roles, responsibilities and practical activities. Annexes include examples of incident criteria based on computer security events and incidents as well as examples of information security events, incident and vulnerability reports and forms.

3.3.4

ISO/IEC 27036-4: Guidelines for security of cloud services

The part 4 of the standard ISO/IEC 27036 has not been published by the date of the creation of this document. According to the working draft [ISOh], it will provide guidance to cloud service acquirers and suppliers aiming to improve the security of cloud services by increasing acquirers’ awareness of the information security risks associated with cloud services, and enabling cloud service providers to persuade acquirers about the identification and management of information security risks related to the services they provide.

3.4

Framework of standards relationships

The standards and guidelines ISO/IEC 27035, NIST SP 800-61 and ENISA’s Good Practice Guide for Incident Management resemble each other presenting a diverse number of similarities. Even though they have different phase descriptions, they provide similar activities that should be considered while following the standards and guidelines.

ISO/IEC standards are developed internationally by worldwide experts in working groups and committees. Therefore a major emphasis on those standards and working drafts is presented at this work.

24 3. BACKGROUND STUDY

Figure 3.4: Framework of published and forthcoming standards

After finding that most of the material regarding incident management in out-sourcing settings is dispersed or planned to be published in the future, a framework of related ISO/IEC standard relationships was created to provide a broad perspective on the topic. The framework shows the relationships on the current standards and the forthcoming ones. This framework can be used as a reference to identify the relationships between the information described in this section and to provide guidance on incident management in outsourcing settings. (See Figure 3.4):

The figure shows inside the bubbles the published standards and inside rectangles the forthcoming standards. The arrows coming from the forthcoming standards to the bubbles indicates which published standards will be complemented with extra sections or by providing guidelines to specifics aspects related to the general topic addressed in the published standard(s).

The standards ISO/IEC 27001 and ISO/IEC 27002 provide good practices that are used as a reference for information security incident management (ISO/IEC 27035:2011). The standards ISO/IEC 27036-(1, 2 & 3):2013+ provide guidance on the evaluation and treatment of information security risks concerning third parties. These guidelines should be considered when performing information security incident management and therefore its relationship with ISO/IEC 27035:2011.

3.5

European ongoing developments

This section introduces relevant projects addressing directly or indirectly challenges regarding incident management in outsourcing settings.

3.5. EUROPEAN ONGOING DEVELOPMENTS 25

3.5.1

European Cloud Computing Strategy

This strategy [EC 12], was launched in September 2012. It aims to identify ways to maximize the potential offered by the cloud . In June 2014, one of the working groups for the implementation of strategy: The Cloud Select Industry Group on Service Level Agreements issued a set of Service Level Agreement standardization guidelines for Cloud Service Providers and professional Cloud Service Customers. The guidelines aim to provide a set of principles to assist organizations, through the development of standards and guidelines for cloud SLAs and other governing documents.

This section describes some Service Level Objectives (SLO) relevant to the case study. The content is, unless specified otherwise, derived from [EC 14]:

4.4 Security incident management and reporting Description of the context or of the requirement

An information security incident is a single or a series of unwanted or unexpected information security events that have a significant probability of compromising business operations and threatening information security. Information security incident management are the processes for detecting, reporting, assessing, responding to, dealing with, and learning from information security incidents.

Description of the need for SLOs, in addition to information available through certification

How information security incidents are handled by a cloud service provider is of great concern to cloud service customers, since an information security incident relating to the cloud service is also an information security incident for the cloud service customer.

Description of relevant SLOsRelevant SLO’s and their requirements: – Percentage of timely incident reports Describes the defined incidents to the

cloud service which are reported to the customer in a timely fashion.

This is represented as a percentage by the number of defined incidents reported within a predefined time limit after discovery, over the total number of defined incidents to the cloud service which are reported within a predefined period (i.e. month, week, year, etc).

– Percentage of timely incident responsesDescribes the defined incidents that are

assessed and acknowledged by the cloud service provider in a timely fashion. This is represented as a percentage by the number of defined incidents assessed and acknowledged by the cloud service provider within a predefined time limit

26 3. BACKGROUND STUDY

after discovery, over the total number of defined incidents to the cloud service within a predefined period. (i.e. month, week, year, etc)).

– Percentage of timely incident resolutions Describes the percentage of defined

incidents against the cloud service that are resolved within a predefined time limit after discovery.

3.5.2

Cybersecurity Strategy

The strategy [EC 13] was published in February 2013, aiming to safeguard an online environment providing the highest possible freedom and security and protecting personal data and privacy. Once implemented, data controllers will be covered by a range of security obligations such as notification of incidents, risk management and participation in coordinated responses.

3.5.3

The Cloud Accountability Project (A4Cloud)

Pearson et al. [PTC+12] describe that this project aims to assist holding each cloud

provider accountable for how it manages, uses and passes on data and other related information, such as personal, sensitive and confidential information. The project combines socio-economic, legal, regulatory and technical approaches.

Accountability The Merriam-Webster dictionary defines accountability as: “an obligation or willingness to accept responsibility or to account for one’s actions”. Accountability is a simple idea defined as “not only should an organization do ev-erything necessary to exercise good stewardship of the data under its control, it should also be able to demonstrate that is doing so” [Pea14]. This demonstration is done by providing detailed information and evidence of the organization’s ac-tions. Papanikolau et al. [PP11] describe the notion of accountability by regulatory frameworks, as a data protection model, which is moving to ‘end-to-end’ personal data protection governance in which the entity that collects the data from the data subject is accountable for the data use and distribution from collection to disposal and during its transit around the globe. Moreover, governance and compliance frameworks such as ISO/IEC 27001/27002 contain elements of accountability such as assurance, transparency and responsibility. For instance the following controls require attribution and separation of responsibility:

A.7.1.2 Terms and conditions of employment, which states that “The contractual agreements with employees and contractors shall state their and the organization’s responsibilities for information security.”

A.7.2.1 Management responsibilities, which states that “Management shall require all employees and contractors to apply information security in accordance with the established policies and procedures of the organization.”

3.6. INCIDENT MANAGEMENT MODELS 27

A.7.3.1 Termination or change of employment responsibilities, which states that “In-formation security responsibilities and duties that remain valid after termination or change of employment shall be defined, communicated to the employee or contractor and enforced.”

Pearson refers to the importance of accountability as follows: “It is important to realize that accountability complements privacy and security, rather than replacing them. If organizations are accountable, they need not just to define and implement privacy and security controls where appropriate, but also define and accept respon-sibility for so doing, show that they are in compliance with privacy and security requirements, and provide remediation and redress in case of failure.”[Pea14]

3.6

Incident management models

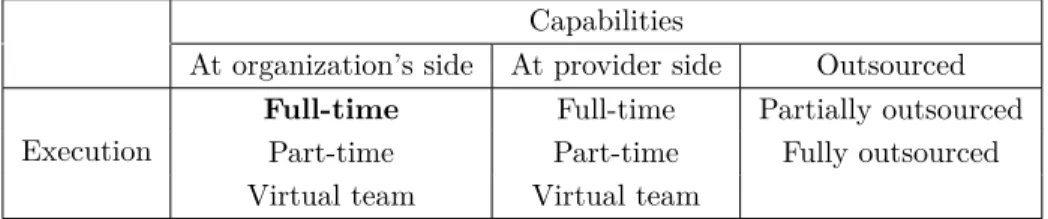

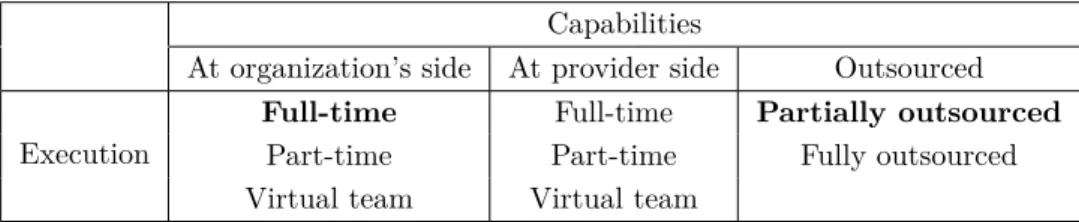

Models of operation and human resource models for CERTs are briefly addressed in the Good Practice Guide for incident Management from ENISA [MRS10]. Based on that information, the incident management models were classified according to how organizations may manage capabilities, personnel and expertise (See Table 3.1).

Capabilities

At organization’s side At provider side Outsourced Execution

Full-time Full-time Partially outsourced Part-time Part-time Fully outsourced Virtual team Virtual team

Table 3.1: Incident management models

– Incident management is executed at the organization side. This model is common on big size organizations and might coordinate also the incident management on the organization’s third parties when third parties are small size companies.

◦ Full time incident response team. In this model the team personnel are fully dedicated to incident response tasks.

◦ Part-time incident response team. This model is usually taken when team members perform not only incident response tasks but also other responsibilities inside the organization.

◦ Virtual team. In this model the personnel is full-time dedicated to different responsibilities and is gathered only to handle an incident.

Each one of these models could be implemented having also collaboration from external experts.

28 3. BACKGROUND STUDY

– Incident management is executed at the provider side. This model might be taken by organizations with limited expertise on incident management, letting the supplier taking care of coordinating the incident response.

◦ Full time incident response team. In this model the team personnel are fully dedicated to incident response tasks.

◦ Part-time incident response team. This model is usually taken when team members perform not only incident response tasks but also other responsibilities inside the organization.

◦ Virtual team. In this model the personnel is full-time dedicated to different responsibilities and is gathered only to handle an incident.

Each one of these models could be implemented having also collaboration from external experts.

– Outsourced incident management. This model is taken by organizations that want to concentrate on core goals or in some cases cut costs.

◦ Incident management or incident response are partially outsourced. This model is taken to avoid delivering a particular service, when in-depth expertise is needed or when there is a lack of qualified personnel. ◦ Incident management is fully outsourced. This model is executed by a

third party providing incident management to the organization and maybe to the supplier too if this one has adopted the same model.

Chapter

4

Case Introductions

4.1

Case A

The organization studied in case A is a Norwegian network (service provider) operator. Throughout the rest of this project, the organization in this case will be referred to as Organization A. The interviewees were the current and former leader of the Computer Emergency Response Team (CERT). Both of them have about 20 years of experience in incident management including both technical and administrative tasks. They were part of the first CERT team in Norway and pioneers in this field. They have mentored other Incident Response Teams and also encouraged them to get into international organizations like the Forum of Incident Response and Security Teams (FIRST).

Organization A is a network provider coordinating the incident response at organizations with limited expertise on incident management. It has a part-time incident response team. Organization A’s incident management model is executed at the organization’s side when in-house incidents are handled. However, for most of the organizations that receive services from Organization A, the latter is the one that coordinates the incident response for the former ones. In other words, Organization A behaves as the provider in the provider side model, for the organizations that receive services from Organization A (See Table 4.1). The interview was mainly addressed taking into consideration the provider side incident management model.

Capabilities

At organization’s side At provider side Outsourced Execution

Full-time Full-time Partially outsourced

Part-time Part-time Fully outsourced

Virtual team Virtual team

Table 4.1: Incident management models in Case A.

30 4. CASE INTRODUCTIONS

4.2

Case B

The organization studied in case B provides a secure network to exchange information in one of the national industry sectors in Norway. Throughout the rest of this project, the organization in this case will be referred to as Organization B. The interviewee was the leader of the Computer Security Incident Response Team (CSIRT).

The interviewee has had two years of experience in incident management including both technical and administrative tasks. Besides, the interviewee has had 14 years of experience performing malware analysis and implementing new detection techniques in a different organization.

Organization B’s model is incident management executed at the organization side. It has a full-time incident response team (See Table 4.2). Some incidents have been managed in cooperation between IRTs in the organization and in the third party.

Capabilities

At organization’s side At provider side Outsourced Execution

Full-time Full-time Partially outsourced

Part-time Part-time Fully outsourced Virtual team Virtual team

Table 4.2: Incident management model in Case B.

4.3

Case C

The organization studied in case C belongs to the public sector. Throughout the rest of this project, the organization in this case will be referred to as Organization C. The interviewee used to hold there the Head of Information Technology (IT) department job position.

Organization C’s model is incident management executed at the organization side (See Table 4.3). It has a part-time incident response team.

Capabilities

At organization’s side At provider side Outsourced Execution

Full-time Full-time Partially outsourced

Part-time Part-time Fully outsourced

Virtual team Virtual team

4.4. EXPERT 1 31

4.4

Expert 1

Throughout the rest of this project, the expert in this case will be referred to as Expert 1. The interviewee was the Chief Information Security Officer from his organization and the leader of incident security response capabilities. He has been dealing with incidents for about 5 years where he has acquired experience in incident management being a manager and supervising teams in Norway. The interviewee has also worked as a technical expert in incident response and as a consultant where he has been pulled in for incident response. The interviewee is considered a technical expert when dealing with incidents in an organization.

Outside his day job, he runs his own company providing support while dealing with incident response and penetration testing. These activities are performed based on his time availability.

Expert 1 works full time in an organization which model is Incident management executed at the organization side. But his own company provides incident response services as an outside specialist to companies which model is Incident management partially outsourced (See Table 4.4).

Capabilities

At organization’s side At provider side Outsourced Execution

Full-time Full-time Partially outsourced

Part-time Part-time Fully outsourced Virtual team Virtual team

Table 4.4: Incident management models where Expert 1 is involved.

4.5

Survey

The Survey was performed with the participation of people with different roles in incident management teams, from a diverse set of organizations, during a course on Incident Response Team Management at the security conference Sikkerhetssymposiet 2014 in Norway. The course leader introduced the survey to the 10 course participants and those willing to participate did it, replies from 6 participants where collected.

Chapter

5

Findings

This chapter presents findings from the case study. The findings from each case are described separately. The information described here is presented as given in the interviews. The findings are organized based on the phases of the standard ISO/IEC 27035 presented in section 3.2.3; the lessons learnt phase as well as the assessment and decision phase were not addressed during some of the interviews and therefore are not presented in the respective case’s findings.

5.1

Case A

This section describes findings from Case A, where the interviewees were the current and former leader of the Organization A’s CERT. Organization A’s CERT performs in-house incident handling most of their time and occasionally performs incident coordination supporting the institutions that receive services from Organization A. Whenever the institutions getting services from Organization A have experienced incidents through these services, Organization A has kept the responsibility, has informed the affected institution and coordinated with it incident response activities.

5.1.1

Plan and Prepare

Organization A is producing best practice documents, open and available to everybody. These best practice documents are produced to the needs of the institutions getting services from Organization A. An Information Security Policy template has been created already and used in processes to aid the organizations and institutions that receive or acquire Organization A’s services with getting an information security in place. The security policy template is based on ISO/IEC 27001 and ISO/IEC 27002 and it has been summarized to a convenient and workable level (25-30 pages). It combines legal requirements and best practices for information security management.

Training and awareness has been provided, the last time was done from 2006 to 2009, covering most of the institutions getting services from Organization A. During 33

34 5. FINDINGS

that time, when the training and awareness exercise was performed, Organization A’s CERT had the ambition to push some of the training’s participant groups into Incident Response Teams. This effort was not successful, only one team appeared. The former leader of the CERT stated:

“In retrospective it was a little bit premature at that time. Now the time is there. Instead of us pushing the course on them, they are asking for it. This is a big difference.”

Organization A’s CERT knows that the effort to train the institutions getting services from Organization A, have provided to the institutions with the knowledge to evaluate what type of incident response is needed, how to react, not to panic, and all the necessary steps to do containment as well as to bring back an attacked system to a clean state. However, some of the people exposed to the training back then, are nowadays somewhere else; they do not hold the same job positions.

Now, the new training and awareness plan from Organization A’s CERT is to run a new course for the biggest institutions getting services from Organization A. These institutions might have enough resources to develop their own Incident Response Team (IRT). After the planned course, Organization A’s CERT will evaluate the outcome and if this strategy is successful and the willingness to participate spreads into the sector, they will make a series of courses.

Regarding cloud services, the former leader of the CERT stated:

“Today there is a clear migration to cloud services. We try to build up for this information leakage, as we consider moving confidential data to any cloud service business. The responsibility is to the cloud service’s customers. It is up to them to make sure that the cloud owner is handling the data correctly. You can’t do incident handling at cloud providers; it is a matter of what kind of agreements you have with them. Unfortunately the last version of the training do not contain any recommendations on this topic . It is something that should be implemented in the future.”

Roles and responsibilities should be documented, which is not necessarily the case. Some institutions, getting services from Organization A, are exposed to standard terms from cloud service providers (take it or leave it). Organization A recommends:

5.1. CASE A 35

– Use common sense

– Think about any situations that can arise and try to make rules that resolve them

– State clearly that any issue with sub-vendors is responsibility of the vendor not the client

Regarding responsibilities that have not been defined beforehand, the former leader of the CERT stated:

“There is always an entity owning the problem. It is like an illness, you can’t say I have cancer it doesn’t regard me. It’s your problem. If I have no agreement beforehand I would try to do anything that would help me getting off. The owner of the data is the one responsible for the problem if it is not stated anywhere.”

Some recommendations to react to this situation were: – A catch-all clause

– Use insurance companies

5.1.2

Detection and Reporting

Detection, at the Organization A’s premises, is occasionally done through complaints, but mainly by their own systems reporting anomalies. There are a number of sensors listening to anomalies. The challenge here is to update them. There is constantly new ways to hack systems or new signatures. It is important to run after the people performing the updates. The current leader of the CERT stated:

“It is a matter of fact that attackers will be always ahead of us.”

Institutions that receive services from Organization A vary on sizes. Some of them are small and do not have an incident response team. The communication is usually clear about who to contact regarding an incident. In general, every institution, including those that acquire services from Organization A, should have a security contact; they do not necessarily need to have a team. The former leader of the CERT stated:

36 5. FINDINGS

“A fire can happen in every house, not every house should have their own fireman, but they should know how to react when the fire sets in, same thing here.”

Organization A’s CERT has trained personnel at the institutions that get services from Organization A. The trained personnel are not an incident response team as such, but they know themselves what to do. It has rarely happened that a hacked system could go for a long time without the intrusion being detected, it is discovered sooner or later.

5.1.3

Assessment and Decision

Organization A’s CERT provides support to institutions getting services from Orga-nization A. Support includes, but is not limited to determine what hits them and how serious is the incident. The former leader of the CERT stated:

“We try to give them information to do wise decisions.”

The common problem in this phase is that the systems in place are getting outdated; the current defenses might not be working anymore because the attackers are using new strategies. The challenge is keeping updated with new developments. Organization A has a strong trademark and the institutions getting services from Organization A have a strong trust over it. The institutions are not afraid to reveal information (even more than what they should) about their infrastructure to handle the incident. The former leader of the CERT stated:

“Trust is not something you can demand, it is something that you earn. It takes time to build trust and it can be loss in one minute.”

5.1.4

Responses

Some challenges that Organization A’s CERT perceive in this phase are:

– Some institutions getting services from Organization A have no experience in incident handling, no time to think about it and no resources.

![Figure 2.1: Different Research Methods, modified from [Yin14]](https://thumb-us.123doks.com/thumbv2/123dok_us/10258364.2931535/20.748.199.554.125.343/figure-different-research-methods-modified-from-yin.webp)

![Figure 3.3: Incident Management and Incident Handling, adapted from [MRS10]](https://thumb-us.123doks.com/thumbv2/123dok_us/10258364.2931535/34.748.134.598.408.678/figure-incident-management-incident-handling-adapted-mrs.webp)