Dear Brands of the World: CSR and the Social Media

Massimiliano Di Bitetto Salvatore Pettineo Paolo D’Anselmi

Article information:

To cite this document: Massimiliano Di Bitetto Salvatore Pettineo Paolo D’Anselmi . "Dear Brands of the World: CSR and the Social Media" In Corporate Social

Responsibility in the Digital Age. Published online: 30 Mar 2015; 39-61.

Permanent link to this document:

http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/S2043-052320150000007004

Downloaded on: 06 June 2016, At: 23:32 (PT)

References: this document contains references to 0 other documents. To copy this document: permissions@emeraldinsight.com

The fulltext of this document has been downloaded 154 times since NaN*

Users who downloaded this article also downloaded:

(2015),"Communicating CSR on Social Media: The Case of Pfizer’s Social Media Communications in Europe", Developments in Corporate Governance and Responsibility, Vol. 7 pp. 143-163 http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/ S2043-052320150000007009(2015),"Using Social Media for CSR Communication and Engaging Stakeholders", Developments in Corporate Governance and Responsibility, Vol. 7 pp. 165-185 http:// dx.doi.org/10.1108/S2043-052320150000007010

(2015),"How knowledge affects resource acquisition: Entrepreneurs’ knowledge, intra-industry ties and extra-industry ties", Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies, Vol. 7 Iss 2 pp. 115-128 http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/JEEE-11-2014-0040

Access to this document was granted through an Emerald subscription provided by emerald-srm:573577 []

For Authors

If you would like to write for this, or any other Emerald publication, then please use our Emerald for Authors service information about how to choose which publication to write for and submission guidelines are available for all. Please visit www.emeraldinsight.com/authors for more information.

About Emerald www.emeraldinsight.com

Emerald is a global publisher linking research and practice to the benefit of society. The company manages a portfolio of more than 290 journals and over 2,350 books and book series volumes, as well as providing an extensive range of online products and additional customer resources and services.

Emerald is both COUNTER 4 and TRANSFER compliant. The organization is a partner of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) and also works with Portico and the LOCKSS initiative for digital archive preservation.

CSR AND THE SOCIAL MEDIA

Massimiliano Di Bitetto, Salvatore Pettineo and

Paolo D’Anselmi

ABSTRACT

Purpose Public sector absorbs a sizeable part of each country’s GDP. Therefore, public organisations are not performing very well at the eco-nomic level of responsibility. Consequently, we argue that in order to build better and more responsible public organisations we need to improve their economic responsibility. This chapter presents a prospec-tive action of social media for business to intervene in public administra-tion reform. We envision a possible course of acadministra-tion that may introduce CSR in the public sector thanks to social media collective action.

Methodology/approach The framework of this study will make a reference to the theory of socio-technological media de Kerckhove and Pierre Le´vy, and on a survey of the literature of citizen activism through social media to answer the question: new media, new message?

It is a new perspective action of social media for business-government relations. We identify a possible theory that leverages the ‘koine`’ of tinational brands to address government effectiveness. The names of mul-tinational companies are the same all over the world, like the ‘Koine’

Corporate Social Responsibility in the Digital Age

Developments in Corporate Governance and Responsibility, Volume 7, 39 61 Copyrightr2015 by Emerald Group Publishing Limited

All rights of reproduction in any form reserved

ISSN: 2043-0523/doi:10.1108/S2043-052320150000007004

39

Greek, and are now a common element in all languages of the world. Citizens and consumers pay a great deal of attention to brands. Multinationals spend millions of dollars every year in public relations (PR) and marketing precisely in order to manage their reputations and images and respond to the requests that consumers have of big corpora-tions. The greatest threat to the reputation of a company or a multina-tional brand comes, in fact, via the Internet, which has become the most powerful weapon in the hands of interest groups. The object of this research is to explore whether stakeholders can join forces with corpora-tions and use global media to monitor governments in the same way.

Findings The citizens of governments and the customers of global cor-porations in different countries in the world seem to be isolated islands: all endure their own battle without the possibility of drawing attention from other parts of the world through social media.

The citizens can exercise pressure on the governments and public administrations the same way as what happens against the brands. It behoves us to ensure responsible behaviour from all. We propose an extension of the use of social media to monitor behaviour of govern-ments as effectively as they are used to monitor behaviour of the corporations.

Research limitations/implications The stakeholder approach to CSR action and reporting implies that the relevant stakeholders of the organi-sation be listened to, and this listening be accounted for in the CSR report. These groups are also called the ‘publics’ of the organisation. We contend that the stakeholder approach might be misused and end up in collusion with sections of the publics involved.

The stakeholder approach leads an organisation to try to engage with the wrong counterparts. This is an over-rating of stakeholders.

Therefore, everything that is not taken into account under the headline of the stakeholder approach we call ‘stewardship for the unknown stake-holder’. The theoretical bases of this value reside in the vast literature on non-maximising, non-efficient, non-effective behaviour by firms and by the employees especially.

Thus, the first task in drawing up a CSR or sustainability report is to identify the possible unknown stakeholders; that is, those who do have a stake but don’t know they do; those who have a stake too small to care about but who are numerous.

Practical implications If we complain about Apple, many in the world will join in; if we complain about the companies that manage the ‘garis’ (as the Portuguese call a garbage collector of Rio de Janeiro) nobody outside Brazil thinks it matters. But in fact, this is not true!

To paraphrase Leo Tolstoy in Anna Karenina, ‘Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way’. Each local public administration will have its own problems, but all in the same way contribute to the well-being or mismanagement of a territory and its citizens. All, to some extent, ill-treated the citizens through their ineffectively.

The CSR should be for everyone and a global movement of citizens ask-ing for responsible governments around the world could be the solution for the well-being of the individual peoples. Let the people’s rights emerge vis-a`-vis perceived needs and outrage about the ineffectiveness of public administration that too often lose the name of action.

In summary, the proposal is the extension of the use of social media to monitor behaviour of governments as effectively as they are used to monitor behaviour of the corporations.

Originality/value We propose a covenant between consumers/tax-payers in order to extend the CSR to governments and public administra-tion. The citizens can exercise pressure on the governments and public administrations the same way as what happens against the brands. It behoves us to ensure responsible behaviour from all. We propose an extension of the use of social media to monitor behaviour of governments as effectively as they are used to monitor behaviour of the corporations, with the help of the same corporations.

Companies would join consumers for two main reasons: because there are clear signs that their company’s reputation is being harmed by the conflict, and because their market performance dips, coinciding with pressure from stakeholders. Our proposal goes beyond this and proposes the concept of a novel social figure: the unknown stakeholder.

INTRODUCTION

Social media are relevant to mainstream CSR as they represent the voice of the various stakeholders with regards to corporations, the ‘global brands’.

Consumers exercise leverage over corporations, which are thus subject to international competition. Governments, public administration and mono-polies, however, are not subject to international competition and are irre-sponsible towards the public, which is unable to use social media to leverage these local institutions. Citizens endure their own battles without getting attention from other parts of the world through the social media: if I complain about Ikea, many in the world will join in; if I complain about the Ulan Bator Transport Authority, nobody outside Mongolia thinks it matters. How can we leverage the global media to monitor governments? In brief, we propose a covenant between consumers and corporations against the irresponsibility of governments.

Social media could contribute to cultural changes and generate aware-ness among all stakeholder citizens that governments are worse than cor-porations. Our theoretical points are the following:

1. The effectiveness of collective action through the social media is tied to general CSR culture, that is corporations are bad. That is why social media maintain CSR control over the brands of the world.

2. Currently, CSR does not focus on governments.

3. Governments should be accountable just as corporations are; however, they are socially responsible only on paper.

4. Governments can be monitored through social media and branded cor-porations, which represent a global koine´, a common language. This is why we want to enlist the corporations in getting governments under control.

5. Our title ‘dear global brands’ implies a dialogue with corporations: ‘We consumers, citizens and workers subject to competition grant that you corporations are better than the governments and can help us get the governments under control’.

6. The mechanism by which brands can be involved is similar to what is already done through ethical investment when investors do not buy stocks in arms makers because governments oppress their peoples with those arms. Investors ‘punish’ the corporations instead of the governments.

This theoretical work will be based on the socio-technological theory on media of de Kerckhove (2011) and Pierre Le´vy (1994), and on a literature survey of citizen activism through the social media to answer the question: new media, new message?

The Object of Our Research: Social Media Stakeholdership Vis-a`-Vis Public Administration

Citizens and consumers pay a great deal of attention to brands. Multinationals spend millions of dollars every year in public relations (PR) and marketing precisely in order to manage their reputations and images and respond to the requests that consumers have of big corporations. The greatest threat to the reputation of a company or a multinational brand comes, in fact, via the Internet, which has become the most powerful weapon in the hands of interest groups. The object of this research is to explore whether stakeholders can join forces with corporations and use global media to monitor governments in the same way. We propose a cove-nant between consumers/taxpayers in order to extend the CSR to govern-ments and public administration.

Why It Is Important: Governments Are More Irresponsible than Corporations

The past few years have witnessed the simultaneous development of the anti-globalisation movement, shareholder activism and corporate govern-ance reform. This trend has cultivated a climate of defigovern-ance toward busi-nesses, which has only been exemplified by recent accounting scandals. Perhaps in response to this growing suspicion, some leading companies have openly profiled themselves as socially responsible. For instance, British Petroleum underlined its commitment to the natural environment by changing its name to Beyond Petroleum. BP is manufacturing better and advanced products enabling the material transition to a lower carbon future (Branding Advertising Public Relations History: Green BP). Similarly, Nike advertises its commitment to adopting ‘responsible business practices that contribute to profitable and sustainable growth’ and Coca-Cola has moved to expense stock options for top management as part of its commitment to responsible governance (Maignan & Ferrell, 2004). Nike Inc. is part of an alliance called Climate Savers. Initiated by WWF in 1999, the Climate Savers programme now counts 30 member compa-nies, including Johnson & Johnson, IBM, Nike, Hewlett Packard, The Collins Companies, Xanterra Parks and Resorts, Sagawa, Sony, Tetra Pak, Lafarge, Catalyst, Novo Nordisk and Nokia Siemens Networks (PR Newswire, 2013).

This is because consumer demand for more responsibility on the part of corporations has become more insistent thanks to the availability of the Internet. The Web has allowed activists to reach millions of people free of charge and explore the problems from the bottom up. Through the Internet, and especially the social media, information is diffused and inter-est groups are created aiming at responsible consumption. Research con-ducted by CONE Communications of 10,000 consumers in 10 countries worldwide revealed that online CSR is experiencing renewed attention. CONE Communications is a public relations and marketing agency in the United States. It is the national leader in corporate social responsibility and cause marketing, and has over three decades of experience in brand communications. Echo. This CSR Study, a follow-up to the 2011 global survey of consumer attitudes, perceptions and behaviours around CSR, was conducted by CONE Communications and Echo Research. 93% of those interviewed declared that they are happier to patronise a company that is socially responsible, and 87% take into consideration the way a company behaves before acquiring its products. Nine out of ten people indicated readiness to boycott socially irresponsible companies, in particu-lar where it concerns the environment and human rights. Additionally, 62% of those interviewed use social media for information concerning the politics of corporate social responsibility of those companies whose pro-ducts they buy. Information concerning the level of responsibility of a com-pany, boycotts or incentives to buy a certain brand is all found online (CONE releases the 2013).

What Others Have Said of It and Their Relevance to What We Have to Say: Many Monitor Corporations, Hardly Anybody Monitors Public

Administration

This enthusiasm for corporate social responsibility has accompanied the growth of online activism. There are many factors that make the Internet attractive for campaigning: its speed of transmission, its capability to reach an enormous number of users both globally and locally, low publishing costs and 24 hour access. The Internet is an important alternative source of information to official and mainstream media, and a powerful means of connection outside of mainstream institutions. It is truly a mass medium, enabling individuals worldwide to share information and converse.

Online activism is the use of electronic communication technologies such as social media (especially Twitter and Facebook, YouTube, e-mail and

podcasts) for various forms of activism to enable faster communications by citizen movements and the delivery of local information to a large audi-ence. A very active form of online activism concerns multinationals (Economist, 2013).

The pressure that can be exerted on multinationals through the web is not restricted to organised groups of citizens. Any single consumer can make use of the inter-connectedness afforded by the Internet. In fact, the following are three historical cases, which effectively demonstrate how big corporations are constantly being monitored by the users of the web.

The first deals with the bicycle locks produced by the famous company, Kryptonite. A customer discovered that these could be easily opened with a simple ballpoint pen and diffused this technique on his blog. This informa-tion was quickly shared by readers and it spread rapidly in discussion for-ums frequented by bicyclists and motorcyclists. Kryptonite immediately denied this information by publishing a communique´ on its site in order to forestall damage to its image but the blogger then published a video demonstrating how to open the locks. Faced with this video proof, Kryptonite had to abandon its defensive stance and act responsibly by admitting the existence of a factory defect in some models and offering to exchange a good lock for the defective one free of charge.

The second case has to do with a defect that was discovered in the bat-teries of the first iPods. Here, too, a particular marketing niche was sha-ken by information passed by various inter-connected blogs. Several thousands of consumers who had bought the iPod organised themselves and filed a class action suit against Apple for defective batteries that ran down too quickly. This episode is significant because the initiative started from the bottom, from a few individual iPod owners who shared the exis-tence of the defect on their blogs and, thanks to the capacity of the web, were able to contact and exchange information with ever greater numbers of people who owned iPods with very little autonomy thus culminating in the understanding that it was not a question of a few isolated cases. The numbers ended up being so high that it became clear that the defect concerned all iPods and in the end, 12,000 Apple customers succeeded in communicating with each other and obtaining a reimbursement from the company.

The last case has to do with certain CDs produced by Sony. In order to prohibit illegal copies, Sony installed software that, unfortunately, acted like a virus when the CD was inserted in a computer, putting the computer itself at risk. It was an American engineer who discovered this problem and published the technical details in his blog. As in the two preceding cases,

the information rapidly spread from blog to blog and Sony was forced to recall the defective CDs.

The following are two more examples of what we call ‘Viral Class Action’. The term ‘viral’ or ‘virtual’ class action is often used in reference to John True et al. (Superior Court of the State of California) in which Honda settled a class action lawsuit that provided Civic hybrid drivers the option to get either a discount off the purchase of a new Honda or a cash payout if they could prove that they complained about the mileage problem to Honda (Superior Court of the State of California). One class member, who thought that the class settlement was unfair, opted out of the settle-ment and went ‘viral’. She filed a small claims court action and turned to social media to encourage others to do the same. She set up a Web site, opened a Twitter account, and posted a video on YouTube to share infor-mation about what is now called a ‘small-claims flash mob’ case, establish-ing a new precedent for rightestablish-ing the wrongs toward the public and openestablish-ing the floodgates for small claims lawsuits.

Another example of a ‘viral’ class action can be seen in a recent wave of small claims court cases filed against AT&T. After one individual success-fully sued AT&T in small claims court over the speed throttling of his unlimited data plan, many more followed. This surge of small claims against AT&T was driven not by a disgruntled class member as it was in theHondacase but by an Internet startup that posted a blog entry claiming to have created a successful step-by-step blueprint for any qualifying indivi-dual to sue the company for alleged data throttling (American Bar Association, 2012).

Possible Effects of Our Hypotheses: Generating Global Demand for Accountability from Public Administration

Ethical consumerism has evolved over the last 40 years from an almost exclusive focus on environmental issues to a concept that more broadly incorporates matters of conscience. During this same period we have wit-nessed a growing debate about the importance of ethical consumerism and, particularly, the impact large-scale strategies have on consumer awareness and spending. This phenomenon has intensified in recent years thanks to the advent of the Web. Political consumerism comes in different forms. Citizens boycott to express political sentiment, and they boycott or use labelling schemes to support corporations that represent values environ-mentalism, fair trade and sustainable development, for example that they

support. Especially young people, though not only, are activists on the Internet, participating in Internet campaigns and using it to voice their individual opinions regarding the consumer society and transnational cor-porations (Devinney, Auger, Eckhardt, & Birtchnell, 2006; Guardian, 2013). Big corporations are always under scrutiny and must act responsibly in order not to become the target of these initiatives.

Consumers are more willing to buy from companies with a reputation for environmental and social responsibility. More businesses have under-stood this and are, in fact, putting into practice the effective use of labels, packaging claims and other means to inform consumers about the environ-mental credentials of their products and services. PepsiCo was the first company in the world to put carbon labels on their packaging. It did so to signal to consumers not only that the company had measured the carbon footprint of one of its best-selling products, but also that it was committed to reducing the embedded carbon of that product within two years. It did this in collaboration with the UK Carbon Trust (Business for Social Responsibility, 2008).

It is these same consumers, geographically dispersed and unacquainted, that put their skills and knowledge together to explore all sides of an issue, publishing on the Internet and linking their sites, correcting each other’s errors and sharing analyses and solutions to problems in an extremely rapid cycle of information, which can become a planetary conversation. All this is so efficient as to succeed in calling into question the reputation of a multinational.

It is not just the blogs but all social media that create a mechanism to influence and control large corporations sufficiently to force them to engage in responsible behaviour. Our use of the term social media includes social networking (Facebook, LinkedIn), blogs (Wordpress, Blogspot), wiki (Wikipedia), microblogs (Twitter) and sites with user-generated con-tent (YouTube).

This Chapter

This chapter consists of three parts. In the first part we have introduced the issue. The key words are ‘citizenship’ and ‘online activism’. We have demonstrated that there is a strong focus on global brands by citizens/con-sumers around the world. We will analyse how this demand for account-ability is not extended to governments, the public administration. We analyse the reasons why citizens/consumers feel they do not have to aim

their actions at controlling governments (which, at the global level, are implemented through the internet and social media). The key words are: ‘monitoring and control’ and ‘irresponsibility of governments’. Finally, we will try to formulate a proposal on the basis of which an alliance can be created between the global brands and consumers/citizens who pay taxes. We will show, in fact, that governments are more irresponsible than cor-porations. Social responsibility is not exclusive to the private sector but must become important also in the public sector around the world. To do this, an alliance is necessary between citizens and Brands. The key words are: ‘unknown stakeholder’ and ‘demand of accountability’.

MATERIALS AND METHOD

Literature Review

The effects of firms collaborating with social movements to influence the practices of other companies, industries or countries have received little attention from researchers.

The theme of web citizen activism has been addressed across multiple locations and in different ways, from different angles. There are economic, political, sociological and anthropological analyses. Almost all the topics that relate to this concept, however, consider the issue from a macro per-spective. For example, the study of the change in climate communication has become an important research field. As stakeholders such as scientists, politicians, corporations or NGOs increasingly turn to the Internet and social media to provide information and mobilise support, a growing num-ber of people use these media and online communication on climate change, and climate politics has become a relevant topic.

We will see later in this chapter that multinational corporations are con-stantly in the crossfire of the discussions that take place on social media. What is lacking are references to literature about the ability to influence the Web on the micro level, the administrative sphere.

Indeed, no studies have focused on the micro level as to the efficiency of local public transport, urban decor or public lighting. This can be seen in many areas where specific scientific literature exists on the impact that social media could have on the level of the administration of public affairs at the local level. From this point of view, therefore, the present study is configured as one of the few exceptions.

Citizen web activism and the limited literature on this subject do not consider citizen stakeholdership towards national and local government (American Grizzlies United).

Extending Monitoring of Stakeholders to Public Administration

Below are some considerations that support the contention that our chap-ter provides the missing piece of the whole jigsaw puzzle.

All companies are efficient in the same way; are all bureaucracies ineffi-cient in their own way? The attention that citizens and consumers pay to multinationals is missing towards governments.

There are two reasons for this. On the one hand, governments are gener-ally perceived as inherently ‘good’, their task that of serving citizens in a responsible manner (to the point that very few talk about the social respon-sibility of governments). On the other hand, governments are perceived as specific and unique while multinationals are global and general. If there are cases against a government they are macro in nature against corruption, for instance, or action to lower unemployment rates but not against long lines at service windows or holes in residential streets. Consider, for exam-ple, the so-called ‘Arab Spring’.

Let’s consider in a more specific manner how responsibility is for everybody, that all organisations should be accountable for their social responsibility.

International companies are easy to talk about: everybody knows them, everybody thinks they know them, a great deal is said about them. Monopolies are more difficult to deal with: the names are no longer famil-iar; they are often local companies; everybody tends to think they have their own predicament which is different from that of others. Nobody is interested in Lilco (the Long Island Lighting Company, in New York), and speaking of Electricite´ de France (EDF) might be regarded as an exqui-sitely European matter, even though Lilco and EDF are very similar to any large power company from around the world. The non-profit sphere can be somewhat similar to international corporations as there are world-class non-profit organisations but, when we come to public administration or government bureaucracies, when we come to politics and political systems, everybody is on his own. It is the war of all against all notwithstanding the well-known and primary impact of government on development.

Thus, millions of employees live in the ultimate autarky; that is, doing everything unsupervised no benchmarking, no comparison, no cross-country learning. Marginal attempts are made in the technical fields,

like information technology, where once again international cor-porations, driven by the need to sell their products, play the significant role of inseminating diverse government and public bodies with the same ideas. Public administration appears to be tied too much to the history of a given country and its legal system. How many times have we heard the theme: ‘They have Roman Law and we have Common Law so we cannot compare’, or vice versa? Public administration is bound by language. To many people, it is heresy to have their official government documents translated into English, as they do in Sweden and the Netherlands.

Comparative public administration is the realm of lawyers and constitu-tionalists with their bird’s eye view approach. American poet Gertrude Stein wrote ‘a rose is a rose is a rose’, meaning things are what they are and we can’t fiddle with them for our own little purposes but all of this ignores the simple fact that, paraphrasing Stein, a jail is a jail is a jail: many government services are identical all over the world. Reality is the same everywhere and human beings are the same. Universal rights are recognised but, in spite of this universality in ‘demand’, no universality to ensure those rights is pursued.

Thus, it is not difficult to understand and adhere to the libertarian con-cept that the peoples of different countries are held hostage by their gov-ernments. Suffice it here to report one more professional point of view on the deficiencies of bureaucracies. ‘Bureaucratic practices rely heavily on symbols and language of the moral boundaries between insiders and outsi-ders, a ready means of expressing prejudice and justifying neglect. Thus, societies with proud traditions of generous hospitality may paradoxically produce at the official level some of the most calculated indifference one can find anywhere’, (Herzfeld, 1992). Nonetheless, all this having been said, we are going to embark now on a short trip across our theory of CSR in government.

IDENTIFYING A THEORY

We identify a possible theory that leverages the ‘koine`’ of multinational brands to address government effectiveness.

Koine` is the Ancient Greek dialect that was the lingua franca of the empire of Alexander the Great and was widely used throughout the Mediterranean area in Roman times. It is a common language among

speakers of different languages. The names of multinational companies are the same all over the world, like the ‘Koine’ Greek, and are now a common element in all languages of the world.

There is little collective web action towards local government and local monopolies whereas we observe a substantial body of evidence of collective web action towards global and multinational corporations and brands. Our curiosity, then, is whetted: would it be possible to spur collective web action towards government and monopolies?

We notice that collective action towards governments does take place in cases of major social and political upheavals such as the ‘Arab Spring’ and the Syrian crisis.

With this chapter we mean to address collective action towards govern-ment and monopolies at an administrative and ‘sub-criminal’ level, at a quality-of-service level, like what is done in the institutional campaigns of Me´decins Sans Frontie`res (Doctors Without Borders) towards Novartis and the Indian Glivec for patent lawsuits; Monsanto and genetically modi-fied seeds; the actions against Nike after which, in 1996, an article appeared in ‘Life’ accusing the company of using child labour in producing balls in Pakistan.

Accordingly, it is desirable to introduce the concept of ‘unknown stake-holders’ (Di Bitetto, Gilardoni, & D’Anselmi, 2013). When CSR is inter-preted as ‘accounting for work’, it is for all organisations, not only for private businesses, and it is also to be exerted in the core business of the organisation itself. The crucial task, then, becomes avoiding irresponsibil-ity non-responsible behaviour rather than putting forth specific good behaviour. Then there is a need for a process framework to account for work. Stewardship of the unknown stakeholder is a value that is part of this process framework. Caring for the unknown stakeholder is one of the ways to detect irresponsibility in the behaviour of an organisation. The unknown stakeholder is he who does not share a voice, who doesn’t even know he has a stake in the activities of the organisation being analysed. It may be a newborn baby who will breathe what will be left of the air seventy years from now. It may be the reasonable solution to a problem that is proposed by wise people and that local voters turn down, spurred by emotions and demagogy. Stewardship of the unknown stakeholder implies, first, identifying the competitive context surrounding the organisa-tion that we are observing. Within this framework, comparisons of perfor-mance must be made with competitors and, in the case of government organisations or monopolies, international benchmarks must be provided. Possible government subsidies must be accounted for under this heading.

When we identify economic phenomena in the internal functioning of a company or an institution, particularly intangibles and externalities, then we are listening to the unknown stakeholder. He is at the heart of all research, the silent critic inside us.

We start this illustration of the unknown stakeholder guiding value by explaining where the centrality of stakeholders comes from. We want to start this treatment of the unknown stakeholder with a reference to the the-ory of stakeholders that has so permeated CSR indeed, has given birth to it. The stakeholder approach appears to be prevalent and is the preferred way to go about implementing CSR and reporting of it by the public rela-tions industry, which is the leading supplier, retained by corporarela-tions to run CSR programmes and write CSR reports.

The stakeholder approach to CSR action and reporting implies that the relevant stakeholders of the organisation should be listened to, and this lis-tening should be accounted for in the CSR report. So, we read section headings in the reports that list the generic names for the groups of stake-holders: stockholders, employees, customers, suppliers and the rest. These groups are also called the ‘publics’ of the organisation. We contend that the stakeholder approach might be misused and end up in collusion with sections of the publics involved. It is not enough to run a two-hour focus group with opinion leaders to understand the issues and to certify that the CSR behaviour of the organisation is satisfactory. For instance, it may not be enough to get the go-ahead of the in-house trade unions to demonstrate that the organisation has fair employment practices: there might be collu-sion between management and employees on high-salary practices or ineffi-cient labour organisation all things that are against the best interests of consumers and the general public.

The stakeholder approach leads an organisation to try to engage with the wrong counterparts; for instance, interviewing young people as repre-sentatives of future generations, as a major power utility did. Headquarters representatives of stakeholder organisations are very prestigious to inter-view, but they may not be very interested or knowledgeable about the spe-cific interviewing organisation. They may have to interface dozens of such organisations and not have anything specific to say. This is an over-rating of stakeholders.

Therefore, everything that is not taken into account under the headline of the stakeholder approach we call ‘stewardship for the unknown stake-holder’. The theoretical bases of this value reside in the vast literature on non-maximising, non-efficient, non-effective behaviour by firms, and by the employees especially.

Thus, the first task in drawing up a CSR or sustainability report is to identify the possible unknown stakeholders; that is, those who do have a stake but don’t know they do; those who have a stake too small to care about but who are numerous, whose protection would be the government’s task; those the weak who do not have a press office.

The unknown stakeholder can be taken into account in behaviour and in reporting of organisations with the help of a taxonomy of organisational sectors that reveals possible content of CSR according to the economic sec-tor the reporting organisation belongs in. Three years after its infamous 2005 survey on CSR, The Economist updated its position on the subject with a second survey on 19 January 2008. The good news is that, while the first survey was scathing in its judgment, this time space was given to John Ruggie (2008), from the Harvard Kennedy School: ‘The theological ques-tion whether CSR exists or not is irrelevant today. The real question is not whether, but how CSR is done’. Of relevance to how CSR is done is a counterargument from none other than Milton Friedman, in 1970: ‘A com-pany’s social responsibility is to make a profit’. Friedman’s indictment appears terrible, especially when applied within the context of countries that fall miserably short when their governments are charged with monitor-ing their own companies and bureaus. Milton Friedman had in mind an ideal form of capitalism when he said that What is necessary, then, is to specify under what conditions profits are made and what kind of capitalism are we talking about.

Accounting for the unknown stakeholder is one way to identify potential irresponsibilities on the part of the organisation. As a first step to identify-ing the unknown stakeholder, the competitive arena of the business should be provided. We thus derive a taxonomy of the general content of the CSR report by sector of the economy. Government and monopolies should pro-vide indicators of activity; businesses subject to competition should conduct research and disclosure on their activities.

Table 1summarises our proposal.

Quantitative Support of Our Hypotheses

The link between the individual economic unit and its socio-economic environment is established in our proposed reasoning through the Porter (1990) and Porter and Kramer (2006) model of competitive advantage, whereby the individual economic unit is at the centre of a diamond whose

four points represent other, different types of economic and social units that affect the performance of the unit at the centre. These four types represent:

1. Context for firm strategy and rivalry: the roles and incentives that gov-ern competition.

2. Local demand conditions: the nature and level of sophistication of local customer needs.

3. Related and supporting industries: the local availability of supporting industries.

Table 1. Social Actors and Type of Control. Social Actors Stake and Motives Brands and

Corporations

Type of Control

Activists Outrage against violation of human rights and consumer rights Nike, Novartis, Monsanto, Honda, Apple, Sony, etc.

DIRECT: global consumers sanction directly the brands/ corporations that are violating human rights or producing inefficient products (e.g. boycotting) thought thekoine`of the brands and social media

Ethical investors Outrage against vice and war

Producers of arms, tobacco, alcohol, gambling, etc.

INDIRECT: global investors sanction the producers of critical goods in order to indirectly sanction the users of those goods

(e.g. governments: arms, alcoholics: alcohol) Unknown stakeholder Outrage against government ineffectiveness Suppliers of governments: IBM, Alstom, Airbus, etc. INDIRECT: irresponsible governments and public administrations make ineffective use of products and services provided by the branded corporations; taxpayers and present unknown stakeholders can exercise pressure on the branded corporations in order to make governments and public administrations accountable for their work

4. Factor (input) conditions: pressure of high-quality, specialized inputs available to firms.

Examples of such ancillary units include: appropriate supply of man-power through the educational system; appropriate logistics for delivery of outputs and an appropriate judicial system. When the unit at the cen-tre of the diamond is immersed in an environment where the economic units surrounding it are effective and efficient (appropriate), then the unit at the centre enjoys a competitive advantage vis-a`-vis other units in its own industry that do not enjoy such an effective economic and social environment.

When the unit at the centre enjoys a competitive advantage, then we say the micro-conditions for economic and employment growth are satisfied. We have established the micro macro link we were looking for. The logic here is the following: the basic economic model of interaction between eco-nomic units in society is that of Michael Porter’s competitive advantage.

Porter’s model includes all economic units private businesses as well as public institutions and everyone is required to generate their added value. Private businesses do not succeed in a vacuum, they succeed in an environment of working and functional public institutions (and, we would add, strong political, democratic and civil society institutions); otherwise private business languishes, government budgets run up large debts and people are unhappy.

The condition for the economic success of a business at the micro level and of economic and employment growth at the macro level is that all other businesses and institutions operating around the business at the micro level are effective and efficient. Since government is among these institu-tions, we call this virtue accountability rather than effectiveness. So for the economic unit to be successful, its environment needs to be accountable. Note that the competitiveness of one unit presupposes collaboration from the units surrounding it, which is why we can also use the term ‘collabora-tive advantage’. Effec‘collabora-tiveness is driven by competition/collaboration. Literature argues that accountability, that is efficiency and effectiveness, of all units ancillary to the competitiveness of the unit at the centre of the dia-mond is a function of those same ancillary units being immersed in an envir-onment that is as competitive as the envirenvir-onment where the first unit resides. Efficiency and effectiveness are a positive function of competition, as is accountability. In a complex modern society, reporting for work or receiving a salary is no guarantee of the effectiveness of the work performed, according to theorists of bureaucratic behaviour (Niskanen, 1968, 2001),

of X-efficiency (Leibenstein, 1978) and of administrative behaviour (Simon, 1997). Such effectiveness is measured both at the micro level of the indivi-dual organisation and at the macro level of the social consequences of work not done or badly done, once again linking micro to macro performance.

Considered in relation to each economic unit of society, be it public or private, the systemic concept of the collaborative/competitive advantage translates into the concept of the effectiveness and accountability of work. All work. As stated by Herman ‘Dutch’ Leonard, ‘all organisations should be accountable for their social responsibility and this new social account-ability can best be constructed for different kinds of organisations introdu-cing the concept of ‘competition’ both within and across industries and sectors. The best way forward is to use the knife of competition to hone the social performance of all organisations’ (D’Anselmi, 2011). This is in order to find a micro-logic that is compatible with macroeconomic success. Our micro macro theory, therefore, is that growth and employment can only be achieved through the accountability of work in all sectors of the econ-omy public, private; monopolistic and subject to competition; for profit, non-profit. Only work that is subject to competition, measure, evaluation, and benchmarking is socially productive and efficient. Only competition and collaboration with the stakeholders (customers, users, suppliers and citizens) leads to quality in products and services.

The Porter diamond gives us a very rich picture of social dialogue and identifies a number of stakeholders so that the whole workforce is embraced. We can partition the workforce according to whether or not it is subject to competition, in order to establish who is contributing to eco-nomic growth and employment. Using this criterion, we identify four dif-ferent sectors:

• government;

• monopolies;

• large corporations;

• MSMEs (Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises).

These four sectors include entire industries and all the workers in them, with no distinction as regards hierarchy or capital ownership. We then pro-ceed to investigate the level of collaboration that these four different sectors are contributing to the economy as a way of quantifying the results of social dialogue and its fairness. Running the arithmetic of the stakes, as theory predicts, reveals that the monopolistic sectors are earning a rent at the expense of the sectors that are subject to competition. Far from

collaborating in the economy, entire sectors of workers are earning rents at the expense of other workers.

Competition provides a certificate of accountability. It does not provide society with a guarantee that the firm or the organisation will behave cor-rectly, but it does guarantee that having the opportunity to adopt com-peting goods and services society can do without a company that behaves badly. Competition does not rule out the need for awareness, man-agement and reporting of corporate social responsibility (CSR). The brands are accountable because they are scrutinised by citizens and consumers through social media.

Salaries of workers of public administration are more relevant than the profits of corporations. Work and productivity is more relevant than the labour capital dialectic. There are a number of aspects to the ‘evasion of work’:

• over-compensation of employees;

• over-compensation of production factors; excessive cost of procurement, as proven, for instance;

• inefficiency;

• non-production/loss of GDP.

In the wake of the economic crisis of 2008, not a single job was lost on the left-hand side of the competitive divide. (More proof of the lack of accountability of those who are not subject to competition. Only in Greece, in 2011 and 2012, after much ado, were jobs lost in the government sector.) Such ‘immobility’ also translates into overcompensation in the sectors that are not subject to competition. The competitive divide identifies new and contemporary kinds of ‘haves’ and ‘have nots’. In a medium-sized economy (23 million workers), an estimated 100 billion per year of over-compensation in the non-competitive sectors is at stake. This is the lower limit of the damage generated by evasion of work and it is the ‘prize’ of the silent class struggle between the competitive and the non-competitive sec-tors of the economy.

The following figure illustrates the methodology used to estimate this value: workers not subject to competition earn 35% of the total salaries in the country, while they make up only 25% of the workforce: the extra 10% of over-compensation they earn amounts to 100 billion. This is no small prise and it appears worth fighting for (Fig. 1).

Non-competitive and non-monitored sectors represent 35% of income and 25% of people over a total income of 1,100 billion (400 billion versus 700 billion), whereas an egalitarian/competitive model would generate a

distribution of 300 billion versus 800 billion. This 100 billion difference (obtained by subtracting 300 billion from 400 billion) is the extra revenue of non-competitive jobs. This is what Niskanen calls the extra cost of pro-duction factors in non-competitive environments.

For those who are subject to competition, it appears more fruitful to fight over-remunerated labour than to fight capital. Capital can fly away. Labour can’t. The idea here is not so much for those who are subject to competition to appropriate the extra revenue of those who are not, but to promote the delivery of full productivity to society by those who are not subject to competition. Thus, the calculation is a minimum estimate of the social value that is redeemable when competition or better, accountabil-ity is established within society. The previous calculations were income-based, but impact-based calculations lead to much larger numbers. It has been estimated that one-third of gross domestic product is lost through lack of infrastructure, lack of purpose in government, mediocre education, and lack of competition and monitoring in services.

Non competitive

35%

Salaries ratio Number of workers ratio

Non competitive

25%

Competitive

65% Competitive75%

Fig. 1. Salaries versus Number of Workers Ratio.

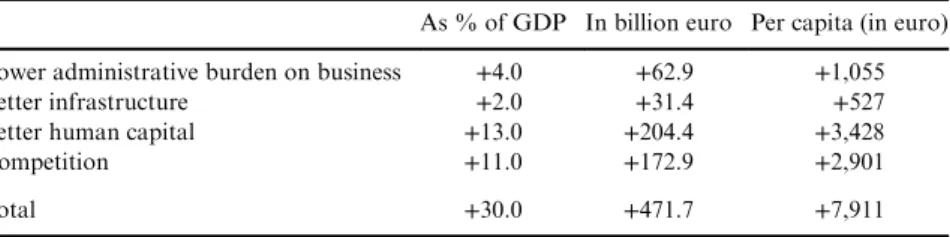

Table 2. GDP 2030 Predicted Changes. GDP 2030, Changes at Constant Prices vis-a`-vis 2008

As % of GDP In billion euro Per capita (in euro)

Lower administrative burden on business +4.0 +62.9 +1,055

Better infrastructure +2.0 +31.4 +527

Better human capital +13.0 +204.4 +3,428

Competition +11.0 +172.9 +2,901

Total +30.0 +471.7 +7,911

Table 2shows that Italian GDP could grow by as much as 30% by the year 2030. Competition and monitoring can be introduced into different public institutions. (An empirical demonstration of this argument is con-tained in a 2002 report by one of Europe’s European National Antitrust Commissions. Those exporting sectors that are more dependent on sectors that are the most problematic from the competition point of view show lower growth rates than the less dependent sectors. Evasion of work ties down those who work and export or efficiently serve the domestic market.)

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, consumers and citizens have a lot of leverage over multina-tional (or global) corporations. They have leverage especially over those corporations that make products. Products are inherently more subject to evaluation than services, they are easier to evaluate over time and space. Thus the multinational (or global) corporations are more subject to inter-national competition. Such public leverage over interinter-national corporations is exercised also through the global social media, which help coalesce dif-fused interests into one strong voice. The same public leverage through the social media does not appear to be exercised vis-a`-vis governments and monopolies that are inherently local. Government here means public administration; we are talking about that 25% of the workforce that is sheltered from competition and the 50% of the economy that is managed through government programmes: for example your local police precinct, your local health care unit, your local transportation company, utilities and so forth. It is the governments, public administrations and monopolies that are behaving irresponsibly. The citizens of governments and the customers of monopolies in different countries in the world seem to be isolated islands: all endure their own battle without the possibility of drawing atten-tion from other parts of the world through social media.

How can we leverage global social media to develop the same kind of monitoring over governments and monopolies that has developed over multinational corporations? Is there a way? We cannot make consumers and citizens do all the work by themselves. In order for us to develop such monitoring, we should involve multinational corporations the brands of the world in the local arena. Consumers and citizens could leverage their power over the world brands to get them involved in domestic matters, for example by asking the world brands that produce buses to monitor the

quality of the local transportation authorities and municipalities. The basic scheme would be to involve the brand or global corporation that is closer to, adjacent with or supplying the domestic problem. This would attract attention from users of that brand worldwide and, therefore, attract world-wide attention to a domestic problem that is experienced globally, albeit fragmented in the guise of individual domestic problems. Global corpora-tions are also very welcome to take issue with the public authorities that are paid to take care of competition matters, to take care of running the courts and enforcing law and property rights.

Companies would join consumers for two main reasons: because there are clear signs that their company’s reputation is being harmed by the con-flict, and because their market performance dips, coinciding with pressure from stakeholders. Our proposal goes beyond this and proposes the concept of a novel social figure: the unknown stakeholder (see section ‘Identifying a Theory’).

The unknown stakeholder can exercise pressure on the branded corporations in order to make governments and public administrations accountable for their work. This is a proposal for a covenant between con-sumers and global corporations against the irresponsibility of governments. Dear Brands of the World, help us obtain accountability from the gov-ernments and public administrations. It behoves us and you to ensure responsible behaviour from all.

REFERENCES

American Bar Association. (November 20, 2012). Class actions 101: A new “Viral” class, action?Retrieved from http://apps.americanbar.org/litigation/committees/classactions/ articles/fall2012-1112-class-actions-101-new-viral-class-action.html

American Grizzlies United.Introduction to citizen activism, American Grizzlies United (AGU). Retrieved from http://americangrizzlies.com/pdf/introduction-to-citizen-activism.pdf. Accessed on August 19, 2013.

Branding Advertising Public Relations History: Green BP. Retrieved fromhttp://prezi.com/ dmxfbzm9zsug/green-bp

Business for Social Responsibility. (April 2008).Eco-Promising. Retrieved fromhttp://www. bsr.org/reports/BSR_Eco-Promising_April_2008.pdf

CONE releases the 2013. CONE communications/echo global CSR study. Retrieved from

http://www.conecomm.com/2013-global-csr-study-release

D’Anselmi, P. (2011).Values and stakeholders in an era of social responsibility. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

de Kerckhove, D. (2011).Digital knowledge, with Annalisa Buffardi. Naples: Liguori Editore.

Devinney, Auger, Eckhardt, & Birtchnell. (2006).The other CSR: Consumer social responsibil-ity. Retrieved from http://www.academia.edu/286306/The_Other_CSR_Consumer_ Social_Responsibility

Di Bitetto, M., Gilardoni, G. M., & D’Anselmi, P. (2013).SMEs as the unknown stakeholder: Entrepreneurship in the political arena. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Economist (The). (January 5, 2013).Everything is connected. Can internet activism turn into a real political movement? Retrieved from http://www.economist.com/news/briefing/ 21569041-can-internet-activism-turn-real-political-movement-everything-connected

Guardian (The). (August 13, 2013).Can consumer boycotts change the world?Retrieved from

http://www.theguardian.com/sustainable-business/consumer-boycott-change-world

Herzfeld, M. (1992).The social production of indifference. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Leibenstein, H. (1978).General X-efficiency theory and economic development. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Le´vy, P. (1994). L’Intelligence collective. Pour une anthropologie du cyberespace. Paris: La De´couverte.

Maignan, I., & Ferrell, O. C. (2004). Corporate social responsibility and marketing: An integrative framework.Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science,32(1), 3 19. Niskanen, W. A. (1968). Non-market decision making The peculiar economics of

bureau-cracy.American Economic Review,58(2), 293 305.

Niskanen, W. A. (2001). Bureaucracy: A final perspective. In W. A. Shughart & L. Razzolini (Eds.),The Elgar companion of public choice. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Porter, M. E. (1990).The competitive advantage of nations. New York, NY: Free Press. Porter, M. E., & Kramer, R. (2006). Strategy and society: The link between competitive

advan-tage and corporate social responsibility.Harvard Business Review,84(12), 78 92. PR Newswire. (January 29, 2013).Yingli green energy joins WWF’s climate savers program.

Retrieved from http://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/yingli-green-energy-joins-wwfs-climate-savers-program-188790941.html

Ruggie, J. (2008). In the Stream, Survey on CSR,The Economist, January 19. Simon, H. (1997).The administrative behavior. New York, NY: Free Press.

Superior Court of the State of California. John True et al. v. American Honda Motor Co., Inc., No. 5:07-cv-287-VAP-OP (C.D. Cal.). Retrieved from http://www.clgca.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/Notice-of-Entry-of-Final-Approval-Order.FINAL_.3.16.12-w. Exs_.pdf

WEBLIOGRAPHY

Erik, S. (February 9, 2010). Huffington Post, “The Coming Wave of Social Media Class Actions”. Retrieved from http://www.huffingtonpost.com/erik-s-syverson/the-coming-wave-of-social_b_703918.html

Guardian (The). (March 8, 2012). #FAIL: authenticity is the key to avoiding social media screw-ups. Retrieved from http://www.guardian.co.uk/sustainable-business/authenticity-social-media-sustainability-communications?INTCMP=SRCH

P2P Foundation, Contribution to the critique of the political economy of the Internet. Retrieved from http://p2pfoundation.net/Contribution_to_the_Critique_of_ the_Political_Economy_of_the_Internet

1. 2015. When two worlds collide. Strategic Direction 31:9, 12-14. [Abstract] [Full Text] [PDF]