‘I was in prison…’

An exploration of Catholic prison ministry in Victoria

Prepared for

Catholic Social Services Victoria, and

CatholicCare - Archdiocese of Melbourne

By Ruth Webber, PhD

October 2014

---

Catholic Social Services Victoria

383 Albert St | East Melbourne Victoria 3002 | Australia

www.css.org.au

TABLE OF CONTENTS

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

... 3Background ... 3

Summary of Findings ... 4

RECOMMENDATIONS ... 7

PART A: LITERATURE REVIEW ... 9

Introduction... 9

Training of prison chaplains ... 9

Role of the prison chaplain ... 9

Role of prison volunteers/visitors ... 12

Impact of Prison Ministry program ... 13

Summary of research findings ... 18

PART B: PRISONS AND CHAPLANCY ARRANGMENTS IN VICTORIA

... 19The Victorian Prison System... 19

Chaplaincy Arrangements in Victoria ... 19

The Chaplains’ Advisory Committee ... 20

Multi Faith Prison Chaplaincy Leaders Group ... 21

Catholic Prison Ministry - Victoria ... 21

PART C: CATHOLIC PRISON MINISTRY RESEARCH PROJECT - 2014

... 23Aim ... 23

Method ... 23

The Ministry Team ... 24

Impact on Prisoners ... 32

Impact on Ex-Prisoners ... 51

Impact on Family Members ... 52

Reactions to Catholic Prison Ministry ... 57

Administration ... 59

Conclusion ... 59

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Background

Catholic Social Services Victoria and CatholicCare - Archdiocese of Melbourne commissioned a study to conduct an exploration of the operations of Catholic Prison Ministry in Victoria in the light of previous research findings on the efficacy of prison chaplaincy. The purpose of the study was to provide information about and insights into the Ministry in order to improve it, and to increase awareness within and beyond the Catholic community about the work undertaken by prison chaplains and volunteers.

The study was conducted by Dr Ruth Webber who is a Professor (Honorary) at Australian Catholic University. Data was collected from a number of sources including interviews, written statements, participant observation and analysis of documents and other written material. Thirty-three people including chaplains, volunteers, prisoners, ex-prisoners, family members and others associated with Catholic Prison Ministry were either interviewed or provided written statements about the Ministry. The report contains rich descriptions of the views of participants including verbatim statements from ex-prisoners and family members. Both groups were overwhelmingly positive about Catholic Prison Ministry and the impact it had on their lives. When asked how this Ministry could be improved, ex-prisoners said that the number of chaplains and volunteers should be increased so that they were available when a prisoner needed spiritual and emotional support.

Across Victoria, there are eleven publicly operated prisons, two privately operated prisons and one transition centre. Catholic Prison Ministry provides chaplains for all prisons. Catholic chaplains, volunteers and priests who celebrate Mass and prisoners who identify as Catholic form the core Catholic faith community at each prison. The chaplains consist of ordained priests, members of religious orders and lay people. CatholicCare – Archdiocese of Melbourne administers Catholic Prison Ministry in Victoria.

Prison volunteers are members of the Chaplaincy and Pastoral Care Team who work in partnership with the chaplains in all prisons. Volunteers who are members of the Hospitality Group offer hospitality and assist in religious services at each of the prisons. Some also visit prisoners in the area outside the chapel. They interact with prisoners and provide emotional support. They usually are rostered on a monthly or fortnightly basis at the different prisons.

A review of literature on the efficacy of intervention by Chaplaincy Services to persons incarcerated in civilian prisons found little research in Australia but a considerable amount in the United States of America and the United Kingdom.

The present study of Catholic Prison Ministry substantiated previous findings on the efficacy of prison chaplaincy in respect to prisoners’ adjustment to incarceration, ability to reflect on their life and move forward, re-connection to their faith and to reframe or avoid infractions. The Catholic chaplains in this study undertook similar roles to those described in international studies, although the former spent a larger proportion of their time interacting with prisoners, ex-prisoners and their families than reported elsewhere. Like previous studies this study found that the non-custodial nature of the chaplain’s role within the prison system assisted in building trust among prisoners.

The study adds to the existing body of knowledge and provides new insights and wisdom into the impact of prison chaplains on the lives of prisoners, ex-prisoners, family members and the prison environment.

Summary of Findings

Roles

The role of prison chaplains goes far beyond just looking after the religious and spiritual needs of the prisoners. The study found that the role of chaplains is multi-faceted and includes:

a) assisting prisoners in their personal and spiritual development, e.g. through liturgy, and prayer;

b) helping prisoners to come to terms with their situation and to make a commitment to improve their lives,

c) administering and organising religious programs and instruction; d) counselling, visiting in residential units and other units;

e) administrative tasks, e.g. organising religious services, conducting memorial services, writing reports, attending meetings, recruiting and coordinate volunteers;

f) providing emotional support to prisoners and family members through counselling and pastoral care;

g) providing practical support to prisoners by assisting with parole inquiries and other paper work.

Chaplains also provide some support to prisoners and family members of prisoners and ex-prisoners. They liaise with and make referrals to other support services inside and outside prison. They also undertake advocacy work for individual prisoners and in respect to the wider justice system.

Motivation

The study found that members of the Catholic Prison Ministry team became involved in Catholic Prison Ministry for altruistic reasons such as responding to a call by God to help the poor and needy and to provide spiritual and other kinds of support to prisoners. While previous studies documented instances of chaplains trying to convert prisoners to a particularly faith tradition (Pew, 2012; Thomas & Zaitzow, 2006), there was no instance of Catholic chaplains or volunteers attempting or wishing to convert prisoners. Any form of proselytising was actively discouraged by the Coordinator of the Ministry who stated that it was not only against the formal agreement with Correction Victoria, but was most inappropriate.

Impact of Ministry

The study found that prison chaplains and prison ministries have an important role to play in supporting prisoners, ex-prisoners, and families as well as enhancing the general running of prisons by providing calming influence. By assisting prisoners to cope emotionally, chaplains provided them with the opportunity to reflect on the reasons for their incarceration and to re-establish connections to their faith and to its underlying moral framework. Some prisoners made good use of this

the outside. It also provides opportunities for prisoners to take on leadership roles and in so doing to channel their energies in meaningful and beneficial ways.

Without exception, the prisoners and ex-prisoners in the study remarked that the service providers and activities brought light to their days in prison, helped them adjust psychologically to

incarceration, and gave them hope of a better life both within and without the walls. Prisoners, ex-prisoners and their families claimed that the Catholic Prison Ministry made a substantial difference to their lives and expressed their gratitude for the ways in which the chaplains had assisted them. The study showed that as a result of this Ministry:

a) the self-worth of prisoners is enhanced.

b) prisoners cope better with prison life and are more hopeful of the future. c) the likelihood of self-harm by prisoners is decreased.

d) prisoners feel less isolated. e) prisoners reconnect to their faith.

f) prisoners are able to deal with guilt and shame. g) prisoners are calmer and less volatile.

h) prisoners are assisted to stay connected to family and friends.

The study provides details about how the Chaplaincy and Pastoral Care Team actually go about assisting prisoners to turn their lives around, which will provide a guide for others who are involved in prison ministry.

Ministry Team

The study concluded that Catholic Prison Ministry is conducted with professionalism by an experienced and dedicated team of chaplains and volunteers. The providers of the service, both religious and lay, are committed to the tasks required; they are non-judgemental, maintain a high degree of confidentiality and are well regarded by the participant prisoners and ex-prisoners. The study concluded that the chaplains and other members of the Catholic Prison Ministry team are well regarded by Prison Authorities, prisoners, ex-prisoners and the families. This regard was based on the ways in which members of the team fulfilled their obligations to Corrections Victoria (2009, 2011) and acted towards the prison community. Participants said that chaplains and volunteers:

a) demonstrate confidentiality;

b) show respect and courtesy to all groups of people that they encounter in their Ministry; c) faithfully adhere to the rules of the prison and the agreement that have been signed with

Corrections Victoria;

d) provide emotional, spiritual and pastoral care to those who request their help without discrimination;

e) assist prisoners to find ways to deal with their grief, guilt, trauma and other concerns; f) challenge prisoners to address their behaviour and to help them to find a new ways to live; g) provide practical assistance and advice to prisoners and their families including helping them

Reduced Infractions

Ex-prisoners reported that they and other prisoners were involved in fewer infractions such as disciplinary misconduct, rule violations and violence as a result of Catholic Prison Ministry. Interviews revealed that there were five main reasons for this reduction in infractions. Firstly, prisoners who attend religious events look out for each other and try to extricate fellow chapel attendees away from potentially volatile situations. Secondly, chaplains help prisoners increase their self-esteem, address their past and to develop strategies to avoid trouble while inside. Thirdly, the chaplains provide emotional support, which results in a reduction in prisoners’ stress levels, with the result that they are less likely to get angry and have aggressive outbursts. Fourthly, the chaplains act as a calming influence on the prisoners and the prison itself. The respect shown to prisoners by the chaplains rubs off on prisoners. Chaplains provide a moral road map through their example and religious teaching; this can remind prisoners of the faith of their childhood and act as a deterrent to undesirable behaviour. Lastly, there is a reduced amount of time and opportunity for prisoners who attend religious events to be involved in infractions. Each religious activity involves between one and two hours per week with chaplains interacting with prisoners in the yards and other areas at other times. Further, prisoners are less likely to be involved in incidents in the front of a highly regarded chaplain.

Post-release – Parish contact

Some chaplains assisted prisoners to successfully re-enter the community by linking them into pro-social resources and connecting them to organisation that helped them gain employment and overcome key re-entry obstacles. Some chaplains, particularly those from religious communities, maintained on-going contact with prisoners and their family, at the request of the prisoner or the family. The study noted that many ex-prisoners found referrals to parish life after release beneficial. Regrettably, others did not find this level of acceptance or were reticent to approach a congregation in case they were not well received. Members of parishes can be anxious about having contact with former prisoners, with their anxiety increasing if ex-prisoners are struggling to overcome mental health issues or drug addiction. Assistance in helping priests and members of Catholic Parishes to develop strategies to include and support ex-prisoners in the life of the parish is required. Pressure on chaplaincy resource

Whilst it appropriate to repeat the high esteem prisoners and ex-prisoners hold for the provision of the Chaplaincy service, this is maintained in part because the chaplains in the study put in many more hours than would be expected in a normal working week. The Catholic faith community contributes both financially and in kind to the Catholic Prison Ministry. Prison numbers in Victoria have doubled over the past two decades with a further 15% increase over the past twelve months. The Victorian Government and the Archdiocese of Melbourne will need to increase the present level of funding in order that the high quality of care can be sustained and services expanded in the face of rising prison numbers and the accompanying rise in administrative tasks, i.e. data collection and analysis, development of recruitment and other materials, selection and training new recruits, and maintaining relationships with prison authorities and relevant organisations. The work of the Catholic Chaplaincy and Pastoral Care Team provides a great service to prisoners, their families and to the prison environment. It should be maintained and expanded and financed adequately.

RECOMMENDATIONS

1. The Catholic Prison Ministry Chaplaincy and Pastoral Care Team needs to be strengthened and its work extended to include more volunteers and chaplains.

This Ministry responds to the issues faced by people in prison, and post-release according to Catholic Social Teaching. The Ministry reaches out to a disadvantaged and often vilified group of people. It encourages personal and social change. The Ministry is a clear response to the Gospel message and needs support. Chaplains are members of their faith communities and are authorised by and accountable to that faith community. This places them in a unique position to provide confidential emotional and spiritual support to prisoners. Chaplains are not employed by Prison Authorities or by Corrections Victoria. The chaplains work long hours which often involves evenings and weekends as this is often the most convenient time for them to contact prisoners, families of prisoners and ex-prisoners. They are stretched ‘thin’ in trying to each meet the needs of prisoners, prisoners’ families and ex-prisoners.

The Catholic Prison Ministry is an effective service in supporting prisoners in their personal and spiritual lives. In order to maintain the quality of the work undertaken and to meet the needs of a growing prison population the resources allocated to this Ministry need to be increased.

2. Further funding is needed in order that the Chaplaincy team can meet the needs of an increasing prison population.

Prisoner numbers in Victoria have been building rapidly: Victoria’s prison population has more than doubled over the past two decades from 2,272 in 1993 to 5,762 in 2013 (Jesuit Social Services 2014, p2). The prison population has increased by a further 15% over the past 12 months: there were 6,247 prisoners in Victorian prisons on Friday, 25 July 2014, 824 more than 12 months earlier.1 The Victorian Government ought to meet some of the cost of meeting the religious and spiritual requirements of this additional number of prisoners, in part because many of the benefits of

chaplaincy also serve the interests of prison authorities. The Catholic community is the logical source for funding of the remaining requirements of the Catholic Prison Ministry.

3. The number of prisoners that it is reasonable to ask a chaplain to serve needs to be ascertained.

There has been an increase in the number of prisoners in recent years and this has increased the workload of chaplains. A work study might be useful in helping to quantify a reasonable staffing ratio and a method developed to meet the shortfall.

4. Promotion of the work of this Ministry needs to be undertaken so that the Catholic community and the wider community are aware of the benefits of this Ministry and the support it needs to continue.

Parish members are often unaware of the importance of Catholic Prison Ministry and the extent and value of the work undertaken by chaplains and volunteers. Promotion of the work of this Ministry will assist in recruitment of chaplains and volunteers. It will also assist in addressing the concerns and fears that parishioners have about having ex-prisoners among them. It will help prisoners to rehabilitate if they feel that they are welcomed by the community.

5. The post-release program needs to be developed and extended, with a well-articulated program and set of guidelines.

The post-release arm of the Catholic Prison Ministry needs to be financially supported to provide staff members who are able to meet the needs of this group of people. The efficacy of a prisoner post-release arm of Catholic Prison Ministry needs to be explored including the possibility that new appointees are not necessarily also prison chaplains.

PART A: LITERATURE REVIEW

Introduction

This section of the report outlines research findings on a number of aspects of Prison Ministry. It begins with a discussion of the role of prison chaplains and prison visitors or volunteers. This is followed by an examination of research findings on the impact of Prison Ministry and religious conversion on recidivism and prison infractions.

The United States leads the research into prison chaplaincy and Prison Ministry whilst research on chaplaincy and Prison Ministry in Australia is sparse. Accordingly, many of the research findings sited in this report come from outside Australia.

Recent research into prison chaplains and Prison Ministry has tended to access three sources of data depending on the research focus and the research questions posed. Research that is focussed on the role of chaplains often uses interviews or surveys with chaplains as the informants. Research that explores the relationship between prisoner adjustment and religiosity often uses data based on interviews with inmates or former inmates and on psychological tests. Research on recidivism rates and prison infractions frequently comes from prison data or other written records. The surveys frequently contain an adaptation of scales designed to measure outcomes. Cullen, Lutz, Link and Wolfe’s 1989 correctional orientation depression scale is one such measure (Sundt, Dammer and Cullen, 2002). Other scales assess adjustment, rehabilitation or program effectiveness. The Maryland Scientific Methods Scale is a tool that is used for assessing the effectiveness of justice related programs (Dodson, Cabage and Klenowski, 2011).

It has been noted the correctional researchers frequently ask about what works in prison but fail to ask an equally important question “How does it work?” (Muruna, 2002). This absence is viewed as a deficit in research in this area and indicates that addressing this question is timely.

Training of prison chaplains

The research shows that chaplains are sometimes viewed with suspicion by prison staff who see them as a hindrance, and just another group who need monitoring. In the past, security breaches by chaplains have been found in prisons, which have contributed to a negative view of chaplains and prison volunteers by prison staff. In many prisons now it is mandated that chaplains receive training in Clinical Pastoral Education or the equivalent (Coleman, 2014). This means that chaplains must undertake hours of practical work and have been assessed as to their effectiveness for prison ministry. Chaplains and volunteers are also trained in the operations and culture of jail; this involves them exhibiting “security mindedness" at all times (Steven, Swanson, & Warner-Robbins, 2014, p.22).

Role of the prison chaplain

Previous research has identified a number of specific roles that chaplains tend to adopt which involve both secular and sacred tasks (Hicks, 2008; Pew, 2012; Sundt and Cullen, 1998). The emphasis that is placed on different aspects of a chaplain’s role differs from prison to prison, with some aspects of the role being undertaken by prison volunteers or occasionally by prison staff.

An analysis of the research into the roles that chaplains adopt revealed that these roles could be grouped into four non-exclusive categories: religious, administrative, personal and political (Table 1).

Table 1: Typical Roles undertaken by prison chaplains found in previous studies.

Religious roles: leading worship services, engaging in religious instruction, engaging in spiritual counselling, conducting memorial services

Personal support roles: counselling, assisting prisoners diffusing hostile situations, liaising and providing moral support to families of prisoners /offenders, supporting ex-prisoners and their families post release.

Administrative roles: recruiting and supervising volunteers, administering and organising religious programs and instruction, engaging in administrative tasks: paper work, reports, mail,

correspondence or data entry, providing educational programs

Policy and/or political roles: advocating for the provision of effective rehabilitation resources, promotion of healing and reconciliation & changes in community attitudes from retribution to restoration, providing input into the policy debate e.g. working towards restorative justice.

Chaplains occupy a unique place in the prison by offering a ministry to prisoners, their families and to prison staff. Unlike correctional officers the chaplain’s role is not custodial but supportive and caring. Accordingly chaplains occupy a position between offenders and their custodians (Sundt & Cullen, 1998, 2002 & 2007).

Religious roles

The religious roles that chaplains typically adopt involve such activities as: leading worship services and religious educational programs as well as engaging in religious instruction and spiritual

counselling. These religious and spiritual roles include encouraging the personal and spiritual development of offenders/ prisoners and accepting them as valuable people in the community (Velona, 2000). An Anglican priest who worked in prison ministry expressed it thus:

The relationship between the Christian church and the prison system is a long standing and honourable one. ... The relationship has always been based on the understanding that each of us is made in the image of God and no one can be given up as lost (Fleming, 2000, p.1)

Adhering to prison rules sometimes results in restrictions being put on inmates’ ability to practice their faith. Beckford (2010) who studied prison chaplaincy in the United Kingdom found that Buddhist, Hindu, Jewish, Muslim and Sikh prisoners were not always permitted to celebrate their religious festival or to fulfil their regular obligations at the appropriate times. While this was less applicable to Christian prisoners, there were still times when restrictions were placed on religious activities. In response to these restrictions chaplains sometimes were required to modify religious programming in ways that allowed inmates to practice their faith without violating prison rules (Hicks, 2008).

Personal support role

Previous studies have found that chaplains provide personal support to prisoners in a number of ways. For example they assist prisoners to make parole plans, visit families, attend inmate award ceremonies, conduct memorial services, organise death notification as well as diffuse hostile

situations between prisoners and between prisoner and their families (Velona, 2000). They also provide moral support to families of prisoners/offenders during the times inmates are in prison and after their release from prison.

Prison chaplains provided counselling in a range of areas including pastoral counselling, grief counselling and marriage counselling. In this way they help prisoners to find purpose and meaning in their lives which reduces the likelihood of depression (Maruna, Wilson & Curran (2006). Sundt, Dammer and Cullen (2002) assessed the role of 500 prison chaplains employed in the United States in offender rehabilitation. They found that chaplains actively support rehabilitation and view offender adjustment and rehabilitation as goals of their counselling. The preferred styles of counselling were those that emphasized modelling and rewarded pro-social moral attitudes and behaviour consistent with religious perspectives.

Administrative Role

Chaplains have a large number of administrative tasks including preparing death notices, co-ordinating volunteers, and assisting prisoners with parole applications. They are also frequently responsible for recruiting and supervising volunteers, and administering and organising religious programs and instruction. They have a great deal of paper work to do (reports, mail,

correspondence, and data entry). Many chaplains administer educational programs and manage treatment programs for substance abusers, at-risk juveniles, and ex-offenders.

Activities within prisons need to be scheduled well in advance of determinate times, especially in high security establishments, as arrangements need to be made for escorting prisoners to these events. This means that there is no guarantee that prisoners will arrive in time. Beckford (2001) claims that these restrictions partly explain why there is a lack of spontaneity and flexibility in the conduct of religious activities.

Policy and/or political roles

In recent times chaplains appear to be more actively involved in advocating for the provision of effective rehabilitation resources for prisoners as well as for alternatives to imprisonment. Their involvement in policy debates and in an endeavour to make the prison system more humane takes place within the prison system as well as at government level. Some chaplains are actively involved in working towards establishing programs that promote and facilitate restorative justice programs. An important aspect of this role is to work towards the promotion of healing and forgiveness. Sarre and Young (2011) who are two Australian academics claim that many faith-based practitioners, particularly from a Christian tradition, can be been found at the forefront of programs designed to reconcile offenders with those whom they have harmed. Sr Velona (2000) who works in an

Australian prison as a chaplain sees the various chaplaincy roles as interconnected, with each playing a part in assisting the prisoners in their personal and spiritual development in addition to offering an alternative perspective to punitive justice, in the hope of changing public attitudes of vengeance and punitiveness.

Role conflict and other stressors

Prison chaplains are confronted from time to time with challenges associated with trying to meet two competing agendas. A key role of chaplains is to assist and support prisoners, a secondary role is

to support prison officers and to some degree the prison system (Sundt, Dammer & Cullen, 2002). As a result of trying to balance their allegiance to church and state, some chaplains can experience role conflict. Chaplains have been found to identify with the prison’s custodial role while at the same time wanting to minister to prisoners and help them to adjust to prison; consequently attending to these dual roles can be stressful (Sundt & Cullen 1998).

Sundt and Cullen (2007) in a study of chaplains and their employment in prison found that role conflict was associated with higher stress and lower job satisfaction. Exposure to personal danger was also seen to affect level of work stress, but supportive colleagues helped chaplains cope with the challenges of their job and led to higher job satisfaction. In a research report on role fusion by Hicks (2008) it was noted that chaplains experienced tension between themselves and inmates with some inmates making it clear that they did not want to be saved; nor were they interested in rehabilitation, and some were manipulative. Initially some chaplains experienced dissonance while they were being ‘socialized’ into their role between what they thought would be their role and what it turned out to be. Despite these challenges, chaplains have reported high levels of satisfaction with their work and reported low to moderate levels of stress compared to the other groups, particularly when they felt valued and supported at work.

Overseas research found that chaplains experienced role conflict between supporting the prison’s custodial role and supporting prisoners because they identify with the prison’s custodial role while at the same time wanting to minister to prisoners and help them to adjust to prison (Sundt & Cullen 1998).

A criticism directed against some chaplains is that they see their role as trying to convert others to their faith (Thomas & Zaitzow, 2006). According to a survey conducted by the Pew Research

Center's Forum on Religion and Public Life (2012), more than seven-in-ten state prison chaplains (73 per cent) say that efforts by inmates to proselytize or convert other inmates are either very common (31 per cent) or somewhat common (43 per cent). The Pew report also states that a sizable minority of chaplains say that religious extremism is either very or somewhat common among inmates, but an overwhelming majority report that religious extremism seldom poses a threat to the security of the facility in which they work.

Recently, members of faith communities in Australia and overseas have stated clearly that prison chaplains need to serve in contexts in which sensitivity to interfaith and multi-faith is paramount (Chambers, 2013; Ingram, 2009). Further, if prison chaplains possess an ecumenical spirit and support each other in their work some of the concerns about proselytizing can be minimised (Sundt & Cullen, 1998, Coleman, 2003). A qualitative study of prison chaplaincy in England and Wales found that: “participants generated a picture of chaplains no longer being there to convert, but rather to provide a service more focused on the prisoner’s needs, especially for emotional support” (Todd & Lipton, 2011, p.4).

Role of prison volunteers/visitors

Volunteers or visitors play a significant role in Prison Ministry. The role that prison visitors adopt will vary according to the prison and the country. However, generally the role includes tasks such as leading worship services or other religious rituals, leading religious education classes, running prayer or mediation classes, and in some cases mentoring and providing food or clothing to family members (O’Connor, 2004-5). There was a great deal of variation in the type of support provided to families of

inmates by prison visitors. PEW (2012) included a section in its large report on religion in prisons on the role that prison visitors / volunteers play. It indicates that one third of the chaplains reported that religious volunteers mentor children of inmates, and half said that volunteers provide food or clothing or holiday gifts for the families of inmates.

The PEW report (2012) also states that the role that prison visitors play is often focussed on helping people deal with guilt and deal with the many losses in their lives, as well as providing prisoners with access to outsiders. They saw this as a valuable contribution to assisting prisoners to develop pro-social behaviour, and found that prison chaplains were satisfied with the role that religious volunteers played. They gave them high marks for the way they led worship services, education classes and prayer groups but gave them somewhat lower marks for mentoring inmates and their children.

Tewksbury and Collins (2005) conducted a study on the profiles of correctional volunteers, the majority of whom were involved in the chaplaincy program. Most volunteers reported high satisfaction levels with their work. Many had been involved in Ministry work prior to doing this volunteer role and others had convictions before they commenced the volunteer work. The activities in which they were engaged was largely preaching and teaching on religious matters. The volunteers received little training. The reasons they gave for volunteering in this area were three fold: they were serving God, it gave them a chance to convert others to their own faith and it gave their life a sense of purpose. Volunteers also commented on how blessed they feel to be involved in this Ministry (Stevens, Swanson & Warner-Robbins, 2014).2

Sundt, Dummer & Cullen (2008) who have conducted much research on Ministry in prisons conclude that additional attention should be given to the role that religious volunteers play in providing support and treatment to inmates (p.81).

Impact of Prison Ministry program

Religious conversion and religiousness

Many researchers have addressed the question of why inmates become involved with religion in prison (Dammer, 2002; Maruna, Wilson and Curran, 2006; Thomas & Zaitzow, 2006). There are both intrinsic and extrinsic reasons why prisoners attend religious events. There are certainly those who genuinely develop a closer relationship with God in prison and find their religious and spiritual life a source of encouragement and map for how to live their life. Researchers have posited a view that a conversion experience provides many positive side benefits that assist prisoners to cope with life in prison. Religion can be a way of atonement for the wrong that prisoners have done and receive the forgiveness that they need in order to establish their personal self-worth and to feel ‘an inner sense of peace’ (Clear et al., 2000, p58). Maruna, Wilson and Curran (2006) conducted life story interviews with 75 male prisoners who self-identified as prisoner ‘converts’ and described themselves as converted, ‘saved’ or born again. The authors argue that the conversion narrative works as a shame management and coping strategy by creating a new social identify in the prisoner which imbues the experience of imprisonment with purpose and meaning and which provides the prisoner with a

2 In the present study of Catholic Prison Ministry in Victoria it was found that proselytizing was actively discouraged and was not listed as a motivation for engagement in the Ministry.

language and framework for forgiveness and a sense of control. The conversion experience not only provides prisoners with a new identity and membership into a community that welcomes new converts, it also helped them sort out their lives and empowered them ‘to preach to others’ and become an instrument of God.

Dammer (2002) conducted a research project in the US and examined the reasons for inmate religious involvement in the correctional environment. Participant observation and seventy individual interviews were employed to gather the ethnographic data in two large

maximum-security prisons located in the northeast United States. The research differentiated between sincere and insincere inmates. The ‘sincere’ inmates were seen to be more genuine in their religious belief and practice and found religion a motivating factor for their lives. Many inmates felt gloomy about their future and their previous life of crime and saw that the practice of religious life gave them an opportunity to change.

Results indicate that the ‘sincere’ inmates claimed that religion gave them ‘direction’- rules and a way of living; a road map for life, or the future- peace of mind; self-control, enabling them to feel better about themselves (Dammer, 2002, p.39). In contrast, the ‘insincere’ inmates were more likely to be involved in religious activity for less worthy and manipulative purposes with their behaviour failing to reflect the rules or norms of formal religion. These ‘insincere’ inmates claimed that religious involvement provided a number of benefits including: protection from assault, interaction with other inmates, interaction with women volunteers, access to prison resources (e.g. food, tea, cards, coffee, donuts), social reasons, pass contrabands, access to music and possibly early parole.

Other researchers have also provided findings that suggest that some prisoners go to religious events to gain credibility, help their parole chances, material comforts, and access to outsiders and intimate relationships that are less stressful (Clear et al, 1992; Dammer, 2002; Thomas & Zaitzow, 2006).

Religious programs and recidivism

About 60 per cent of those in custody in Australia have been imprisoned before.

The research on

whether faith involvement and praxis in prison contributes to a reduction in recidivism isinconclusive (O'Connor & Perreyclear, 2002; O'Connor, Cayton, Min, & Duncan, 2007; O’Connor 2004-5). There are some studies that have reported an association between religious involvement in prison and low rates of recidivism. For example, Dodson, Cabage and Klenowski (2011) who did an assessment of faith based programs to determine whether they are effective for reducing recidivism concluded that faith-based programs can work to reduce recidivism for certain offenders under certain conditions, but note that much of the research is methodologically weak. Further, the methods and styles of correctional treatment undertaken by chaplains have been associated with reductions in recidivism (Sundt, & Cullen, 1998; Sundt, Dammer & Cullen, 2002).

However, a distinction has been found between the rate of reincarceration and the rate of re-arrest of ex-prisoners. O’Connor (2003) found that religious involvement did predict less rearrest, but did not predict less reincarceration.

Young et al (1995) did find a significant long-term impact of Prison Ministry programs in the United States run by Prison Fellowship Ministries (PFM), a program founded in 1975 by Charles W, Colson

following his own incarceration. Colson was a former presidential aide to Richard Nixon. The results of the research showed over a period of 8 to 14 years the PFM group had a significantly lower rate of recidivism and those who did recidivate took longer to do so compared to the comparison group. Seminars were most effective with lower risk subjects, white subjects, and especially women. The findings suggest that religious programming may contribute to the long-term rehabilitation of certain kinds of offenders. Subsequent research on this program found no difference in median time of re-arrest or reincarceration between the two groups through an eight year study but participants with higher levels of participation in Bible studies were less likely to be rearrested at 2 and 3 years after release, (Johnson, 2004). This re-affirms the importance of personal religious practices such as bible reading and prayer on behaviour.

A study investigated long-term recidivism among a group of federal inmates trained as volunteer prison ministers in a program operated by Prison Fellowship Ministries in Washington DC. The study found that a significantly smaller percentage of the participants in the Discipleship Seminars became recidivists and were arrested at a slower rate following release as compared to the control group (Young, Gartner, O’Connor, Larson & Wright, 1995b).

While some studies have provided evidence of a positive relationship between religion and offender rehabilitation (Dodson, Cabage and Klenowski, 2011; Johnson, 2004; Young et al, 1995a &b), other studies failed to find such evidence (Johnson & Larson, 2003; O’Connor, 1995; Johnson Larsen & Pitts, 1997). Dodson, Cabage and Klenowski (2011, p.374) state that there is a general lack of empirical support for the claim that faith based programs are effective in addressing social ills including criminal behaviour. On balance there seems to be just as many research findings that do not support a positive relationship between attending religious programs and reduced recidivism rates as those that report a relationship. For instance, O'Connor and Perreyclear (2002) found that there was no difference between the religious and non- religious groups in respect to recidivism in their study of inmates in a large medium/maximum security prison in South Carolina.

Research linking religious involvement and reduced recidivism rates should be treated with caution because research in this area is limited and much of it is methodologically weak (O’Connor, 2004-5). For example, one reason for the discrepancy in findings about recidivism and religiosity of inmates is that the methodology has not always been as rigorous as it might and data is not always complete. O’Connor (2004-5, p.23) states “Both religious programming and research into that programming need to improve if society is to benefit from the enormous potential that faith-based services, lives, and interventions have to offer to the correctional systems and cultures in the United States” A number of variables need to be taken into account when attempting to study the relationship between inmate religiosity and a reduction in recidivism rates: these include ethnicity, age, the prison environment, offence, length of sentence, post release support, length of time of re-offence after release and the prison environment. At this point there is not comprehensive and comparable data available.

Religious programs and infractions

Research findings have consistently reported a link between religious involvement in prison and reduced rule infraction violations while in prison. A prisoner who commits an infraction engages in such things as disciplinary misconduct, rule violations and violence.

It is reported that the intensity of religious programming seems to help reduce infractions. In a review of twelve empirical studies it was reported that the strongest effect of religion and spirituality on prison life is a reduction of incidents and disciplinary sanctions (Eytan, 2011). Religious programs address the problem of time on prisoners’ hands and provide a unique opportunity to channel inmates’ energies and use their talents in meaningful and beneficial ways and it reduces the amount of time for brooding and for infractions (Thomas & Zaitzow, 2006). As noted above, O'Connor and Perreyclear (2002) found that there was no difference between the religious and non- religious groups in respect to recidivism in their study of inmates, however, the more religious sessions an inmate attended the less likely he was to have an infraction. Likewise a study conducted by Clear and Sumter (2002), who administered a self-report questionnaire to 769 inmates in 20 prisons in the US, reported that increasing levels of religiousness were significantly related to the number of times inmates reported they were placed in disciplinary confinement for violation of prison rules. The researchers noted that the results differed between prisons in different regions.

Not all research in this area reported an association between religiosity and reduced infractions. A study based on prisoner self-reports did not provide a positive association between the number of self-reported prison infractions and inmate religiosity (Clear & Sumter, 2008).

Religious program and rehabilitation

Researchers have made a distinction between rehabilitation and re-offending. Rehabilitation is more about fitting back into the community and re-establishing contact with their families and former friends. Prison Ministry is not confined to the prison setting. Chaplains typically provide moral support to families of prisoners many of whom feel victimised as outcasts by the general community (Velona, 2000).

The families of prisoners can feel victimised and see themselves as outcasts by the general

community. They can be resentful and hurt by the behaviour of a relative returning from prison and the shame he or she has brought on the family.

Support for prisoners and their families post release has been found to be related to a successful transition back into the community. Parsons and Warner-Robbins (2002) conducted a study of women who had been incarcerated, participated in Welcome Home Ministries and had been released from prison for at least six month in Southern California. The purpose of the study was to describe factors that supported women's successful transition to the community following

incarceration. Twelve themes emerged with ‘Belief in God (Higher Power) as a source of strength and peace in our lives’ ranking the highest and the ‘Nurse-Chaplain’s jail visit and support’ ranking fourth. Parsons and Warner-Robbins (2002) concluded that although there were many factors necessary to support women’s successful transition to community following incarceration, the rank ordered dominant factors are a spiritual belief and practice and being free from addiction. There is much support for the view that faith-based groups are well suited to engage in rehabilitative and re-entry efforts (Earley, 2005).

One study revealed that religion/spirituality was used by former male inmates who were undergoing behavioural change as a form of emotional comfort, a distraction from current stressors, and as a

factor demarcating the transition from deviance to a more conventional life (Schroeder & Frana, 2009). Likewise Maruna (2001) in a British study claimed that religion is one pathway for some offenders to turn their lives around and to “make good”. Similarly, a study of ex-prisoners living in half way houses in the US found that both religion and spirituality assisted in their move away from crime by helping them cope emotionally and develop self-control. It also provided them with relief from anger (Schroeder & Frana, 2009).

Much of the research on religiosity and delinquency indicates that religiosity and delinquency are inversely related, which suggests that faith-based programs, which are rooted in religious

organizations, may be effective tools for reducing deviant and criminal behaviour (Dodson, Cabage & Klenowski, 2011). Prisoners who take on volunteering roles while in prison within the Prison

Ministry program have been found to have higher levels of rehabilitation. Further it has been found that support from religious groups after inmates are released from prison to be absolutely critical to inmates’ successful rehabilitation and re-entry into society (O'Connor & Perreyclear, 2002).

Recent research indicates that religious institutions and other faith based organisations play an important role in aftercare transition and assist former prisoners in gaining employment and in overcoming key re-entry obstacles (Dodson, Cabage and Klenowski, 2011). Thomas and Zaitzow (2006) argue that the value of religion in prisons can be assessed on the degree to which it changes predatory and other socially unacceptable behaviours. Any reduction in this behaviour is a positive outcome for the prisoner and for the wider society.

Some research has been undertaken from the perspective of chaplains who tend to see their role as highly significant to successful rehabilitation. Prison chaplains have been found to be optimistic about their role and the importance of it to prisoners and the wider society. In a study of chaplains and prisoner rehabilitation in the US it was found that four out of five chaplains agreed that

rehabilitation is the most effective and humane cure to the crime problem (Sundt, Dammer & Cullen, 2002, p. 71). The PEW Research Centre (2012) conducted a survey of prison chaplains in all 50 states of the US on Religion & Public Life and found that:

Overwhelmingly, state prison chaplains consider religious counseling and other religion-based programming an important aspect of rehabilitating prisoners. Nearly three-quarters of the chaplains (73%), for example, say they consider access to religion-related programs in prison to be “absolutely critical” to successful rehabilitation of inmates. And 78% say they consider support from religious groups after inmates are released from prison to be absolutely critical to inmates’ successful rehabilitation and re-entry into society.

Facilitate adjustment

Previous studies found that programs conducted by chaplains can help men and women to adjust psychologically to incarceration and to find meaning and purpose in their lives (Coleman, 2014; O’Connor & Duncan 2011).

Summary of research findings

There are conflicting research findings on the relationship between Prison Ministry including chaplaincy and recidivism. However, research findings indicate that Prison Ministry programs have resulted in a number of positive outcomes.

Firstly, research has consistently found that Prison Ministry programs can have a significant affect in reducing inmate infractions. This is an important finding because infractions impact on staff, inmates and on the smooth running of the prisons as well as having financial implications.

Secondly, increased religiosity is associated with lower levels of depression and assist prisoners to adjust to prison life. Acceptance of religious teaching appears to help prisoners deal with guilt and use religious teaching as a way of establishing a road map for the way they conduct their lives.

Further, it is clear that some prisoners establish a relationship with God as a result of being in prison. Thirdly, the chaplains and Prison Ministry team help some prisoners stay connected to their families and community. Fourthly, some prisons are connected with a community as a result of the post release program run by Prison Ministry programs.

PART B: PRISONS AND CHAPLANCY ARRANGMENTS IN VICTORIA

The Victorian Prison System

Across Victoria, there are eleven publicly operated prisons, two privately operated prisons – opeated by the GEO Group at Fulham Correctional Centre, and G4S Custodial Services at Port Phillip Prison - and one transition centre, the Judy Lazarus Centre. The Dame Phyllis Frost Centre and Tarrengower Prison are for women only; the remaining prisons are for male prisoners only. At 30June 2014 there were 406 women in the prison in Victoria – 342 at Melbourne Dame Phyllis Frost Centre, Deer Park and 64 in Tarrengower Prison in Maldon. Originally a farm, the prison was opened in January 1988 after the property was purchased and accommodation units were built. Tarrengower is the only minimum security female prison in Victoria.

Prisoner numbers in Victoria have been building rapidly: Victoria’s prison population has more than doubled over the past two decades from 2,272 in 1993 to 5,762 in 2013 (Jesuit Social Services 2014, p2). The prison population has increased by a further 15% over the past 12 months: there were 6,247 prisoners in Victorian prisons on Friday, 25 July 2014, 824 more than 12 months earlier.3 The Dame Phyllis Frost Centre, Port Phillip Prison, Barwon Prison and the Marngoneet Correctional Centre, Loddon Prison and Melbourne Assessment Prison together with the Metropolitan Remand Centre and the Custody Centre are all within the Archdiocese of Melbourne (O’Shannassy, 2012).

Corrections Victoria4 – a business unit of the Department of Justice – is responsible for prison management in Victoria and for all prisoners in both publicly and privately-managed prisons, including administering the contracts of the two private prison providers. Corrections Victoria is responsible for achieving the appropriate balance between a high level of community safety and the humane treatment of prisoners including focusing on strategies to rehabilitate prisoners in custody. It sets, monitors and reviews standards in both public and private prisons, undertakes business planning, and initiates and manages correctional infrastructure programs.

Another independent business unit of the Department of Justice – Office of Correctional Services Review – reports independently to the Secretary of the Department of Justice on the effectiveness of Corrections Victoria's management of the Victorian prison system.

Chaplaincy Arrangements in Victoria

As in many western countries,5 State authorities in Victoria are involved in organisation of the promotion of religious rights in prisons.

In Victoria prisoners have a legal right to practise their faith under section 47 (1) (i) of the Corrections Act 1986:

3 Corrections Victoria, communication with Catholic Social Services Victoria.

4 This description draws from the Department of Justice website - http://www.corrections.vic.gov.au/home/prison/

5. For example, the chaplaincy program in Canada is administered by the Correctional Services of Canada Chaplaincy Division which

provides chaplaincy services of people of different faiths with the various faiths communities being represented on the Interfaith Committee on Chaplaincy (Corrections Services of Canada, 2014).

(i) the right to practise a religion of the prisoner's choice and, if consistent with prison security and good Prison Management to join with other prisoners in practising that religion and to possess such articles as are necessary for the practice of that religion.

The current practice of prison chaplaincy in Victoria is constructed around this legislation, which thus also enables access to a qualified representative of any religion, attendance where feasible at religious services, and possession of religious books, rosary beads, etc.

Since 1994, Corrections Victoria (including its predecessors) has contracted faith-based agencies to provide chaplaincy services to prisoners. Contractual agreements exist between Corrections Victoria, Fulham and Port Phillip private prisons and the Catholic, Anglican and Uniting Churches, the Greek Orthodox Church, The Salvation Army, the Islamic Council of Victoria (ICV), the Buddhist Council of Victoria (BCV) and the Jewish Faith (Bet Sohar), to provide chaplaincy services to prisoners

throughout Victoria’s prisons. The other faiths and religious have access to religious advisors in prison but they do not have contractual agreements with Corrections Victoria.

The Guidelines for the Provision of Chaplaincy Services in Public Prisons classify the chaplaincy role under five broad headings: religious activities, counselling and pastoral care, welfare, liaison and advocacy and people management i.e. “being a safety valve to diffuse potentially violent situations” (Corrections Victoria, 2011, p.6). The document respects denominational identities, but within a broader chaplaincy program – for example, it provides that: “Chaplains agree to assume pastoral responsibility for any prisoners when requested, regardless of whether that prisoner has nominated a religious affiliation upon reception to prison” (p.5).

Corrections Victoria (2007, p.12) acknowledges the necessity for chaplains to maintain

confidentiality with prisoners. However, it mandates that chaplains advise prison management ‘when a prisoners has revealed any information that poses a security risk to either that prison or another prison’ or if a risk is posed ‘to that prisoner (e.g. self-harm or attempts at suicide) or to any other person within any prison or the community (e.g. threats to harm).’ (Corrections Victoria, 2007, p 12).

In Victoria, prison chaplains have access to private rooms or offices; they can be both female and male, are not always ordained, and come from various faith traditions.

The Chaplains’ Advisory Committee

The Chaplains’ Advisory Committee (CAC) was established by Corrections Victoria under the 2007

Guidelines (Corrections Victoria 2007). It comprises senior representatives of Corrections Victoria and senior representatives of the religious communities of faith who have agreements for chaplains to work in prisons. It meets on a bi-monthly basis with Corrections Victoria and representatives of the two private prisons. It also meets with management of the two private providers annually. It is the main consultative and advisory body in relation to the provision of chaplaincy services in public prisons.

While the CAC provides an effective role in communicating between chaplains and the prison authorities in the areas defined above, the Guidelines make it clear that the CAC is not an independent entity.

Multi Faith Prison Chaplaincy Leaders Group

The Multi Faith Prison Chaplaincy Leaders Group, which has been established by the faith groups, represents the interests of each faith community supporting chaplains within Victoria’s public and private prisons in their relations with the Department of Justice, Corrections Victoria, and the private prison providers. Its role is to promote the sustainability and service development of the faith-based prison chaplaincy service in Victoria (Corrections Victoria, 2009). Membership comprises one

representative of each faith community holding a chaplaincy agreement with Corrections Victoria or the private prisons. The convenor of the Chaplains Advisory Committee is also a member.

The Catholic chaplains meet regularly with chaplains from other faiths, both as part of this Leaders Group and more generally, and endeavour to work co-operatively with them.

Catholic Prison Ministry - Victoria

The Catholic Prison Ministry Chaplaincy Team, which is auspiced by the Catholic Dioceses of Victoria, operates state-wide (CSSV, 2014). It provides a range of activities that cater for the spiritual and emotional needs of an expanding prison population and is underpinned by respect for the human dignity of each person. It is estimated that about 18% of the current prison population is Catholic which is at current levels over 1000 people6. This is a large number of prisoners for chaplains to support.

The mission of Catholic Prison Ministry is ‘to respond to the gospel call to stand with, serve and bring freedom to those who are poor, disadvantaged, oppressed and imprisoned’, and to ‘remember those in prison as though you were in prison with them’ (Catholic Prison Ministry, undated, quoting Hebrews 13:3, etc). Their values are justice, compassion, human dignity, unity, confidentiality and excellence (Catholic Prison Ministry, undated).

Sister Mary O'Shannassy, S.G.S. who is a Sister of the Good Samaritan, has worked in prison chaplaincy for twenty years and is the Director, Catholic Prison Ministry Victoria. Sr Mary is also currently the Convenor of the Chaplains Advisory Committee. She has articulated the rationale behind the Ministry in several forums:

We endeavour to affirm the inherent human dignity of each person - a person with: physical, intellectual, emotional, social and spiritual needs. We aim to enable those in custody to recognise their own dignity and worth, to accept their story without fear and to find some HOPE in their life---all of which assists their rehabilitation. We advocate, when necessary on behalf of these people. In our Ministry to prisoners and their families/friends, we work alongside others who are involved in the care of prisoners. (O’Shannassy, 2014)

We believe that at the heart of our Ministry is to bring the Good News of God’s love to people who, in general, are used to anything but good news. We meet people at their most fragile and honest moments and this is as close as you can

6Prisoners are asked about their religious affiliation when they are first admitted to prison. According to the 2011 Population Census,

25.3% of respondents across Australia identified as Catholic, and 26.7% in Victoria (ABS 2011)6. The percentage of prisoners in Victoria

who identified their religion as Catholic was less than those who identified as Catholic in the 2011 Census. Based on figures accessed on 29 May 2014, 1078 prisoners in Victoria cited their religious affiliation as Catholic, which is 18% of the prison population.

get to the gospel spirit. We try to offer women and men the space to share their story ... so we build bridges of trust. Through our Ministry the prisoners have the opportunity to recognise love in their frequently chaotic lives. As chaplains it is a matter of discovering the goodness that is at work in their live, assisting them in getting to know their God, who has always been there. (O’Shannassy, 2011, p.9)

The symbol of the Catholic Prison Ministry is a rock that is cracked, uneven and hard on the outside, but when you turn it over there are beautiful crystals imbedded in it. This represents the prisoners who see themselves as hard and do not see the beauty in themselves. The Director of the Catholic Prison Ministry, Victoria explained that just as the rock has a beauty within it, so have the prisoners; the Ministry program helps prisoners to find the beauty that is within them.

Catholic Prison Ministry Victoria support prisoners, families of prisoners and ex- prisoners. Among the many aspects of their role, chaplains can attend court with prisoners and ex-prisoners who have no-one to support them, in addition to liaising with organisations which often support to

ex-prisoners. A single person can be engaged in all of these roles. By contrast in Catholic Prison Ministry Queensland, the different aspects of the tasks are separated.

PART C: CATHOLIC PRISON MINISTRY RESEARCH PROJECT - 2014

Aim

The aim of the project was to conduct an exploration of the operations of Catholic Prison Ministry in Victoria in the light of previous research findings on the efficacy of prison chaplaincy programs. The purpose of the exercise was to provide information and insights in order to improve Catholic Prison Ministry and to increase awareness within and beyond the Catholic community about this Ministry.

The study involved delineating and examining aspects of the Catholic Prison Ministry including; a) the roles undertaken by members of the Prison Ministry team,

b) the religious program,

c) training of chaplains and volunteers,

d) impact of the Ministry on the lives of prisoners, ex-prisoners and connected families, e) the administration of the program,

In addition the study sought to ascertain how the chaplaincy program assists prisoners, ex-prisoner, families and the wider prisoner community. Previous research has addressed ‘what’ and ‘why’ questions around prison chaplaincy but not ‘how’ questions (Muruna, 2002; Thomas, 2004-5). This research seeks to address this gap. While other studies have examined possible relationships between Prison Ministry and recidivism, this is beyond the scope of this study.

Method

Data was collected from a number of sources including interviews, written statements, participant observation and analysis of documents and other written material. The research methodology was qualitative, designed to provide a depth of description and analysis of prison chaplaincy; and in particular of the different perspectives on chaplaincy provided by chaplains, ex-prisoners and family members. Ex-prisoners and family members who had contact with the Catholic prison chaplains were invited to take part in the study. Careful steps were taken to gain participantsinformed consent. It is acknowledged that this is not a representative sample of the ex-prisoners and family members who have had contact in recent years with the Catholic Prison Ministry. This does not negate the veracity of the views expressed by participants.

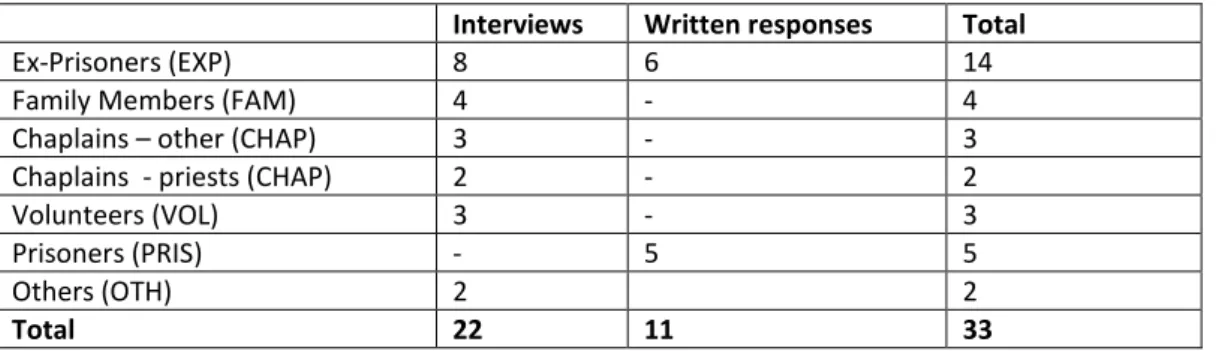

Table 2: Participants in the prison chaplaincy study

Interviews Written responses Total

Ex-Prisoners (EXP) 8 6 14

Family Members (FAM) 4 - 4

Chaplains – other (CHAP) 3 - 3 Chaplains - priests (CHAP) 2 - 2

Volunteers (VOL) 3 - 3

Prisoners (PRIS) - 5 5

Others (OTH) 2 2

Interviews

As part of the formal research investigation interviews were conducted with twenty-two people including: ex-prisoners (8), family members (4), ordained chaplains (2), not ordained chaplains (3), volunteers and two other people who had an association with the program.

Three of the chaplains had worked for more than twenty years in both metropolitan and regional prisons in Victoria; the other two chaplains had been involved in Prison Ministry for less than five years. Two prison volunteers had been involved in the program for twelve years; the other had joined the program more recently.

Written comments

Five prisoners supplied written comments about Catholic chaplaincy during a prison ministry session. Another prisoner sent a card to one of the chaplains with comments about the work of the chaplains and five ex-prisoners provided written comments. Pseudonyms have been used throughout.

Prison visits

In the company of chaplains, and as part of the Worship and Hospitality team, the researcher attended two metropolitan prisons, i.e. Metropolitan Remand Centre and Dame Phyllis Frost Centre7. These visits provided an insight into the work of the Ministry team.

In the next section the results are presented and discussed.

The Ministry Team

The core faith community at each prison consists of chaplains, volunteers and priests who visit on a regular basis to celebrate Mass. The cohort of chaplains consists of ordained priests, members of religious orders and lay people8.

7 The corrections Victoria website http://www.corrections.vic.gov.au/home/prison - provides information on each of the prisons including the following:

The Metropolitan Remand Centre is a maximum security remand prison for men (Corrections Victoria, 2014). It had capacity for 723 prisoners on 30 June 2013, and 798 at 30 June 2014. Accommodation is a mix of single and double cells in variable-sized units. The facilities include: two 77-bed and one 87-bed general accommodation units, one 127-bed protection unit, one 88-bed orientation unit, 204 beds in varied units allocated for special needs such as (but not limited to) vulnerable prisoners, young adult, prisoners at risk and one 13-bed management unit. Each accommodation unit has program and resource facilities, interview rooms and satellite clinics and each area has its own recreational facilities including a walking track and basketball courts.

Dame Phyllis Frost Centre (Corrections Victoria, 2014) is a maximum security women's prison and was built in 1996 as the first privately designed, financed and operated prison in Victoria (Corrections Victoria, 2014). Aside from HM Prison Tarrengower it is the only women's prison in Victoria. As HM Prison Tarrengower is minimum security mainstream, all other female prisoners (medium security, maximum security, and all protection prisoners) are imprisoned at the Dame Phyllis Frost Centre. It has an operational capacity of 344 on 30 June 2013, and 386 at 30 June 2014. Accommodation includes single cells with en suite facilities, self-contained units in addition to two special cell blocks housing twenty prisoners each designed for protection prisoners and prisoners with a history of poor behaviour. Medium security units house ten prisoners in separate rooms while minimum security units house only five prisoners. Each unit has individual kitchen and dining facilities and prisoners are required to cook and prepare their own meals and do their own washing, ironing and housework. Groups of prisoners share activity areas and a quiet area for reading and writing

8 Many prisoners think that chaplains are either priests or members of religious communities. They tend to call them ‘Sister’, ‘Brother’ or ‘Father’.

CatholicCare administers Catholic Prison Ministry in Victoria. There are approximately 22 priests, 20 chaplains and 60 volunteers operating in prisons state-wide in this service. The Catholic faith community contributes both financially and in kind to the Catholic Prison Ministry. The Director, Catholic Prison Ministry Victoria described in an unpublished paper the work that is undertaken by the Prison Ministry team.

Our Ministry with and amongst the women and men in prison is an Emmaus journey. Just like Jesus met the two disciples when they were troubled and concerned and walked with them we also journey with the residents, meet them where they are, listen to their concerns etc and enable them to find some HOPE for that day. We have the opportunity for Mass and Reconciliation and we have volunteers who come into Mass with us. These volunteers form the stable faith community within the different prisons. We distribute Rosary Beads, Bibles to those who request them and give out prayer cards. We had a book mark printed with a special prayer on it for those in custody. (O’Shannassy, 2014)

The chaplains are able to walk around the prison and go into the different units. There are some units such as Management Units, in which greater restrictions are placed on prisoners. Every resident has the right to speak with a chaplain.

Selection and training

One of the main ways that volunteers are recruited is through parishes. The volunteers are screened for suitability and once selected take part in a training program prior to commencing work in the Prison Ministry. The role of the volunteer coordinator is to screen and interview potential volunteers. The training of volunteers is conducted by members of the Catholic Prison Ministry Chaplaincy and Pastoral Care Team, and the CatholicCare volunteer coordinator generally conducts the induction. Volunteers are supplied with information about the duties of the Chaplaincy and Pastoral Care Team, including the Worship and Hospitality Group, the rationale behind the Ministry, and security obligations and issues. Directions on how to travel to the prison which they will be attending are also supplied.

Chaplains usually have a qualification in Clinical Pastoral Education or its equivalent. Catholic Prison Ministry requires chaplains to have previous experience and training in pastoral care. New chaplains learn the specific requirements of prison chaplaincy by accompanying an experienced chaplain on his/her daily round. Prison Management provides specific security awareness training for all

chaplains. This training is mandated and chaplains cannot get approval from Prison Management to take on this role without having received this training. Steven, Swanson, & Warner-Robbins (2014) found that chaplains in the US also receive training in the operations and culture of jail.

Motivation for involvement

Volunteers and chaplains were asked about their motivation for being involved in the Prison Ministry program. The responses of volunteers were relatively consistent, stating that they were responding to the call by Jesus to help the poor and the needy, and on their responsibility as a member of civic society to give their time and skills to assist others. The chaplains provided similar reasons to the volunteers for joining and remaining in the program, and they explicitly stated that they are called by God to this Ministry to provide spiritual and other kinds of support.