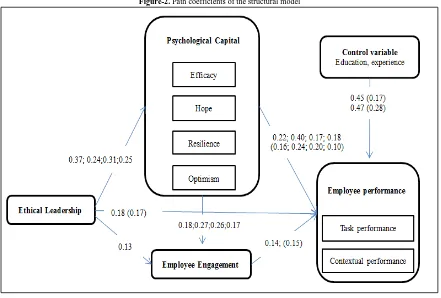

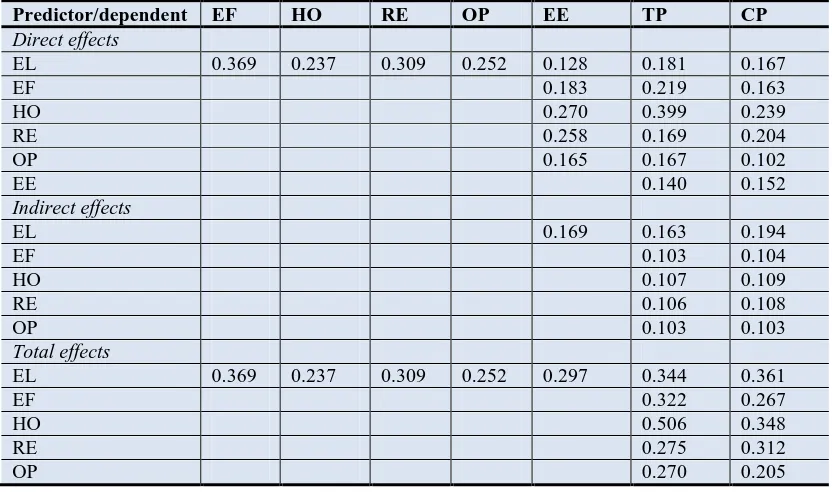

How Ethical Leadership Supports Employee Performance: The Role of Psychological Capital and Employee Engagement

Full text

Figure

Related documents

Default If Customer or any Customer fails to comply with any material provision of this Agreement, including, but not limited to failure to make payment as specified, then Cox, at

We propose a methodology to select variables for predictive modeling purposes out of the plethora of data available using a combination of Oblique Component Analysis (PROC

Such a pedagogy—one that may enhance a student’s ability to embrace and utilize mindfulness while alleviating the insecurities that may arise in the process—derives from the

The exercise involved over 200 participants at the airport including airport and airline staff and manage- ment, fire officers, police, health services responders in- cluding

Methods: In this study, we explored the conditions for efficient expansion of human keratinocyte stem/progenitor cells carrying a transgene with a lentiviral vector, by using

In this specification, semantic signifiers are used for the following purposes: (1) to specify the semantics by which data should be provided to the DSS for

This article analyzes the cost-effectiveness of inpatient substance abuse treatment, using readmission rates as the outcome measure.. Our goal is to identify the characteristics

FIGURE 4.6b: Shannon Diversity indices of the human gut microbiome dataset at the Phylum and Genus levels using the different.. taxonomic profiling methods is shown