Vol. 3, No. 3 (2013): 223-228 Research Article

Open Access

I

ISSSSNN:: 22332200--66881100

Anti-ulcerogenic Activity of the Methanol Extract of

Ceiba pentandra

Stem Bark on Indomethacin and

Ethanol-induced Ulcers in Rats

Chioma A. Anosike* and Raymond E. Ofoegbu

Department of Biochemistry, University of Nigeria, Nsukka. Enugu State, Nigeria

* Corresponding author: Chioma A. Anosike; e-mail: chiomanos@yahoo.com

ABSTRACT

This study evaluated the anti-ulcer activity of the methanol extract of Ceiba pentandra stem bark on experimentally-induced gastric ulcer in rats. Animals were pre-treated with varied doses of the extract and reference drugs- ranitidine and omeprazole. Ulcer was induced in the animals by the administration of either indomethacin (50 mg/kg) or 95 % absolute ethanol (0.5 ml). A total of 20 rats divided into five groups of four animals each were used for each assay. Mean ulcer index and percentage ulcer inhibition by the extract and drugs were calculated for each group. Histological studies of the gastric wall of the ulcer- induced rats were carried out. Ceiba pentandra produced a significant dose dependent inhibition of gastric lesions in both indomethacin and ethanol-induced ulcers evidenced by the reduced ulcer index of the treated groups. Histological examination of the gastric wall of the control rats revealed severe damage of the gastric mucosa, haemorrhages, along with oedema and leucocyte infiltration of sub-mucosal layer while the Ceiba pentandra extract-treated rats showed little damage of the gastric mucosa. These results show that Ceiba pentandra possess ulcer protective properties against experimentally induced ulcers and validates its traditional use in the treatment of stomach pain and ulcer.

Keywords:

Ceiba pentandra, gastric ulcer, mucosal damage, oedema, ratsINTRODUCTION

Gastric ulcer, also known as peptic ulcer disease,PUD, is the most common ulcer of an area of the gastrointestinal tract. It results from persistent erosions and damage of the stomach wall that might become perforated and develop into peritonitis and massive haemorrhage [1, 2]. This occurs as a result of imbalance between some endogenous aggressive factors such as hydrochloric acid, pepsin, refluxed bile, leukotrienes, reactive oxygen species (ROS) and cytoprotective factors, which include the function of the mucus bicarbonate barrier, surface active phospholipids, prostaglandins (PGs), mucosal blood flow, non-enzymatic and enzymatic antioxidants [3-5]. The gastric mucosa protects itself from gastric acid with a layer of mucus, the secretion of which is stimulated by certain prostaglandins. NSAIDs block the function of Cyclooxygenase 1 (COX-1), which is essential for the production of these prostaglandins [6]. Secretion of gastric acid is recognized as a central

component of the gastric ulcer, thus, its main therapeutic target is the control of this secretion using antacids, H2 receptor blockers (ranitidine, famotidine, cimetidine) or proton pump blockers (omeprazole and lansoprazole) [7]. The success of these commercially available antiulcer drugs in the treatment of gastric ulcer is usually overshadowed by various side effects; for example, H2- receptor antagonists e.g. cimetidine,

may cause gynaecomastia in men (enlargement of breast in men, due either to hormone imbalance or to hormone therapy) [8] and galactorrhoea in women (abnormal copious milk secretion [9], while proton-pump inhibitors can cause nausea, abdominal pain and constipation [10]. Due to these side effects, there is a need to find new antiulcerogenic compound(s) with potentially less or no side effects and natural products derived from plant sources have always been the main sources of new drugs for the treatment of various diseases including gastric ulcer [11].

Ceiba pentandra also known as ‘Silk cotton tree’ and locally as ‘Dum’ is a tropical tree of the order Malvales and the family Bombacaceae [12]. The plant is native to Mexico, Central America and the Caribbean, Northern South America, and to Tropical West Africa and is widely reputed in the African traditional medicine. The tree is also known as the Java cotton, Java kapok, Silk cotton or ceiba. Various morphological parts of this plant have been reported to be useful as effective remedies against diabetes, hypertension, body aches, uterine contractions and rheumatism [12, 13]. The plant has also been reported to possess anti-ulcerogenic activity [14]. The traditional medicine practitioners of the Igbo tribe, Nigeria, use a boiled concoction mix which includes the stem bark and leaves of Ceiba pentandra as a remedy for stomach pains. Thus, the present study was initiated to evaluate the anti-ulcer activity of the methanol extract of Ceiba pentandra stem bark.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant material

The stem bark of Ceiba pentandra was collected and identified by Mr. Alfred Ozioko, a Botanist at the International Centre of Ethnomedicine and Drug Discovery, (InterCEED) Nsukka. A voucher specimen was deposited in the herbarium unit of the Department of Botany, University of Nigeria, Nsukka. The plant material was shade-dried after collection and powdered. The powdered plant material was extracted with methanol and filtered with the help of Whatmann paper No. 1 filter paper. The filtrate obtained was dried in a rotary evaporator (IKA, Germany) at an optimum temperature of 40o-50oC. The dried crude extract

obtained was stored in a sterile container.

Animals

Adult male albino Wistar rats (200- 260 g) obtained from the Animal house of the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, University of Nigeria, Nsukka were used for the study. The rats were randomly divided into five groups of four rats each and were fasted for 48 h before the experiment but were allowed free access to water. Throughout the experiment, all the animals received human care in accordance with the ethical rules and recommendations of the University of Nigeria committee on the care and use of laboratory animals and the criteria outlined in the “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals” prepared by the national academy of sciences and published by the National Institute of Health (Pub No.85-23, revised 1985).

Phytochemical analysis

The phytochemical analysis of the extract was carried out based on procedures outlined by Trease and Evans [15].

Acute toxicity LD50 test

The acute toxicity test method described by the Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development [16] was used to determine a safe dose for the extract. Eighteen animals were assigned equally

into six groups labelled 10, 100, 1000, 1600, 2900 and 5000 mg/kg of extract preparation, respectively. The animals were fasted overnight prior to dosing. Food was withheld for a further three to four hours after dosing. Observations were made on mortality and behavioural changes of the rats following treatment.

Effect of Ceiba pentandraextract on indomethacin–

induced gastric ulcer in rats

This determination was carried out using the method of Ubaka et al. [17]. Twenty male adult albino rats were used for the experiment. The rats were randomized and divided into 5 groups of 4 rats each and treated orally with normal saline and varying doses of the plant extract. The extract and drugs used were freshly prepared as a suspension in normal saline and administered orally (p.o) to the animals with the aid of oral intubation tube. Group 1 (vehicle control) was administered normal saline (5ml/kg). Groups 2, 3 and 4 were treated with 100, 200 and 400 mg/kg of the plant extract respectively. Group 5 (reference group) was administered 100 mg/kg of ranitidine (Zantac®), a

standard anti-ulcer drug. Thirty minutes later, 50mg/kg of indomethacin was administered (p.o) to the rats. After 8hrs, each animal in the groups was sacrificed by chloroform anaesthesia and the stomach removed and opened along the greater curvature, rinsed with copious volume of normal saline and pinned flat on a board. Erosions formed on the glandular portions of the stomach were counted and the ulcer index was calculated.

Effect of Ceiba pentandraextract on ethanol–induced

gastric ulcer in rats

Ulcer was induced according to the method of Shokunbi and Odetola, [18]. Twenty rats were randomized and divided into 5 groups of 4 rats each and pre-treated orally as stated above before ulcer induction. Ulcer lesion was established with 0.5 ml of 95% ethanol (p.o.). After 4hrs, the animals were killed by cervical dislocation. The stomachs were removed and opened along the greater curvature and macroscopic examination carried out with a hand lens (x10).

Gross gastric lesion evaluation

Each specimen of the gastric mucosa was examined for damage and the ulcer was counted and scored as 0 = no ulcer; 1 = superficial ulcer; 2 = deep ulcer; 3 = perforations. The sum of all the lesions/ulcer in all the animals for each group (total ulcer score) was used to calculate the ulcer index. The percent ulcer inhibition was calculated relative to control as follows:

% ulcer inhibition (% U.I) = (1- )

Where Ut represents the ulcer index of the treated group and Uc represents the ulcer index of the control group.

Histological lesion evaluation

were made at a thickness of 5 μ and stained with

haematoxylin and eosin for histological evaluation.

Statistical analysis

This was done using SPSS version 17.0 (SPSS Inc. Chicago, IL. USA). All values were expressed as mean ± SEM. Data were analysed by one-way ANOVA and difference between means was assessed by Duncan’s new multiple range. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant between the groups.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Acute toxicity of the extract (LD50 test)

Table 1 shows no mortality in all groups of mice that were administered with C. Pentandra up to 5000 mg/kg body weight.

Table 1. Acute toxicity of the extract

Group No of mice

used Dose (mg/kg) Dead (%)

1 3 10 0

2 3 100 0

3 3 1000 0

4 3 1600 0

5 3 2900 0

6 3 5000 0

Phytochemical analysis of the methanol extract of Ceiba pentandra stem bark

Phytochemical analysis of the methanol extract of C. pentandra stem bark showed the presence of bioactive compounds such as phenols, alkaloids, flavonoids, tannins glycosides, saponnins, resin and terpernoids (Table 2).

Table 2. Phytochemical constituents of the methanol extract of Ceiba pentandra stem bark

Constituents Stem bark

Alkaloid ++

Flavonoid +++

Glycosides ++

Saponins ++

Tannins +++

Resins +

Steroids +

Terpenoids ++

Acidic compounds -

Phenols ++

+++ - Present in very high concentration ++ - Present in moderately high concentration + - Present in small concentration.

- - Absent

Indomethacin-induced ulcer

Indomethacin produced ulcers in all the rats of the groups. Gastric lesions in this ulcer model were seen as blackish spots on the gastric mucosa (Fig 1). Potent and dose dependent ulcer inhibition was observed in all the groups treated with the extract as was evidenced by the drastically reduced ulcerations in the gastric mucosa of the rats (Fig 2) and significantly (p≤0.05) reduced ulcer

index of the groups, which at 400mg/kg, was comparable to that obtained for ranitidine (Table 3).

Figure 1. Gastric lesions in the stomach of control rats administered with indomethacin

Figure 2. Reduced ulcerations in rats pre-treated with 400mg/kg of the extract

Figure 4. Reduced haemorrhage in rats pre-treated with 100mg/kg extract before ethanol administration

Ethanol-induced ulcer

Ulceration in this model was seen as multiple hemorrhagic red bands of different sizes along the glandular portion of the stomach (Fig 3). Pre-treatment with the extract produced significantly (p≤0.05)

reduced areas of gastric ulcer formation in the gastric mucosa (Fig. 4) when compared to the rats pre-treated with only normal saline (vehicle control) (Fig 3). There was significant dose-dependent reduction in ulcer index of the extract treated groups. The ulcer index obtained for the large dose, 400 mg/kg, was comparable to that obtained for omeprazole (Table 4).

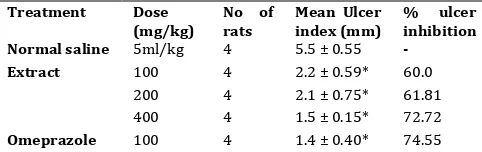

Table 3. Effect of Ceiba pentandra stem bark extract on indomethacin-induced ulcer in rats

Treatment Dose (mg/kg)

No of rats

Mean Ulcer index (mm)

% ulcer inhibition Normal saline 5 ml/kg 4 3.8 ± 0.73 -

100 4 1.2 ± 0.30* 68.4 200 4 1.0 ± 0.24* 73.7

Extract

400 4 0.85 ± 0.15* 77.6

Ranitidine 100 4 0.82 ± 0.30* 78.4 Values shown are mean ± S.E.M (n = 4). Level of significance *= P ˂

0.05

Table 4. Effect of Ceiba pentandra stem bark extract on ethanol-induced ulcer in rats

Treatment Dose (mg/kg)

No of rats

Mean Ulcer index (mm)

% ulcer inhibition Normal saline 5ml/kg 4 5.5 ± 0.55 -

100 4 2.2 ± 0.59* 60.0 200 4 2.1 ± 0.75* 61.81

Extract

400 4 1.5 ± 0.15* 72.72

Omeprazole 100 4 1.4 ± 0.40* 74.55 Values shown are mean ± S.E.M (n = 4). Level of significance *= P ˂

0.05

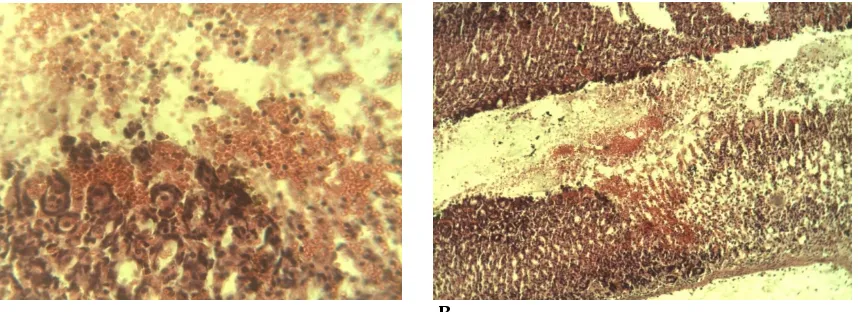

Histological lesion evaluation

The control rats pre-treated with only normal saline before ethanol induction suffered markedly extensive damage to the gastric mucosa. Severe loss of surface epithelium, mucosal haemorrhage, edema and leucocytes infiltration of the sub-mucosal layer was observed (Fig 5). Rats pre-treated with the extract or omeprazole had comparative protection of the gastric mucosa as seen by the reduction in ulcer area, reduced

sub-mucosal edema, absence of leucocytes infiltration to the mucosal membrane and normal epithelial cells. Such protection was more prominent at 400 mg/kg dose of the extract (Fig 6).

This study investigated the protective effects of the methanol extract of Ceiba pentandra stem bark on gastric ulcer formation induced by indomethacin and ethanol, as compared to ranitidine and omeprazole respectively; drugs whose ulcer healing effects have been extensively studied [19]. The main cause of gastric ulcer is the destruction of the gastric mucosal barrier which consists of the surface epithelium and mucosal coat. This destruction may be due to either, an increase in gastric acid secretion or a decrease in mucus production and mucosal blood flow, thus leading to erosion of the gastro-intestinal wall [2].

Using absolute ethanol is a simple method for inducing experimental gastric ulcer in rats resulting in severe gastric mucosal injury. Ethanol shows its harmful effects either through direct generation of reactive metabolites, including free radical species that react with most of the cell components, changing their structures and functions, and promoting enhanced oxidative damage [20]. Ethanol damages the gastrointestinal mucosa by micro-vascular injury, involving disruption of the vascular endothelium, thereby leading to increased vascular permeability, edema formation and epithelial lifting. It produces necrotic lesions in the gastric mucosa by its direct toxic effect, reducing the secretion of bicarbonates and production of mucus. Ethanol is metabolized in the body to release superoxide anion and hydroperoxyl free radicals which are involved in the mechanism of acute and chronic ulceration of the gastric mucosa [21, 22]. Its administration to experimental rats causes disturbances in gastric secretion, damage to the gastric mucosa, alterations in permeability, gastric mucus depletion and free radical production [23]. In this study, all the doses of the Ceiba pentandra stem bark showed potent ulcer inhibition against ethanol-induced ulcer that was comparable to that of omeprazole. Drugs such as omeprazole are proton pump inhibitors and efficiently inhibit gastric acid secretion. [18, 19]. The inhibition of the ethanol-induced ulcer by the Ceiba pentandra extract could be attributed to its antioxidant property and ability to chelate free radicals and reactive oxygen species, thus reducing oxidative damage to the mucosal membrane and epithelial cells. This activity could be linked to the presence of some antioxidants constituents; flavonoids, saponnins and tannins, in the plant. These substances characterized by their polyphenolic nature, have been reported to have cytoprotective and antiulcer activities in other plants [23 - 25]; and perhaps inhibited gastric mucosal damage in this study by scavenging the ethanol generated oxygen metabolites.

A B

Figure 5. Histological section of gastric mucosa of rat pre-treated with normal saline before ethanol induction showing (A) red blood cells indicative of mucosal haemorrhage and (B) severe loss of surface epithelium and sub mucosal edema. H and E stain x 40

A B

Figure 6. Histological section of gastric mucosa of rat showing normal epithelial surface and gastric pits after ethanol induction (A) pre-treatment with 400 mg/kg of Ceiba pentandra (B) pre-treatment with omeprazole. H and E stain x 40

is an established ulcerogen especially in an empty stomach. The incidence of indomethacin-induced ulceration is mostly on the glandular (mucosal) part of the stomach. The mechanism underlying the ulcerogenicity of indomethacin is the secretion of gastric acid and inhibition of prostaglandin synthesis [6]. Inhibition of prostaglandin synthesis triggers the mucosal lining damage since prostaglandins are cytoprotective to gastric mucosa and are essential for its integrity and regeneration. They inhibit acid secretion and maintain gastric microcirculation; stimulate mucus, bicarbonate, and phospholipid secretion; increase mucosal blood flow, accelerate epithelial restitution and mucosal healing. Thus, continuous generation of prostaglandins by the mucosa is crucial for the maintenance of mucosal integrity and protection against ulcerogenic and necrotizing agents [2, 26]. Pre-treatment with Ceiba pentandra extract reduced the indomethacin-induced ulcer by perhaps the mechanism of increased endogenous prostaglandin synthesis which in turn promotes mucus secretion and enhances the mucosal barrier against the action of necrotizing agents. This action could also be attributed to the alkaloids present in the plant which are known to stimulate prostaglandin formation. Reports have shown that plant derived alkaloids have significant activity in acute and chronic gastric ulcers in rats. These alkaloids increased free mucus and prostaglandin production and showed a reduction in hemorrhages and blood cell

infiltration in the gastric mucosa [27, 28]. Ranitidine exerts potent inhibition against indomethacin- induced ulcer due to its anti-secretory potency [17]. Results from this study showed that the stem bark extract of Ceiba pentandra exerted inhibition against indomethacin-induced ulcer that was comparable to that of ranitidine. This result corroborates that of Ibara et al, [14], who also reported the anti-ulcerogenic activity of Ceiba pentandra against indomethacin-induced ulcer. The gastroprotective effect exhibited by the extract of Ceiba pentandra could also be attributed to its anti-inflammatory activity. Extensive damage to the gastric mucosa by indomethacin and ethanol lead to increased leucocyte infiltration into the ulcerated gastric tissue. These leucocytes which are a major source of inflammatory mediators inhibit ulcer healing by mediating lipid peroxidation through the release of highly cytotoxic and tissue damaging reactive oxygen species such as superoxide, hydrogen peroxide and myeloperoxidase derived oxidants [29, 30]. Thus, suppression of leucocyte infiltration during inflammation was found to enhance gastric ulcer healing [31].

CONCLUSION

at high doses, was comparable to that of ranitidine and omeprazole, the standard drugs used.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We wish to thank Mr. Alfred Ozioko, a Botanist at the International Centre of Ethnomedicine and Drug Discovery, (InterCEED) Nsukka for providing us with the plant material used for this study. This work was not funded by any group.

Competing interests

The author(s) declare that they have no competing interests.

REFERENCES

1. Yuan Y, Padol IT, Hunt RH. Nat Clin Pract Gastroent Hepatol

2006; 3: 80- 89.

2. Wallace JL. Physiol Rev 2008; 88: 1547-1565.

3. Phillipson M, Atuma C, Henriksnas J, et al. Am J Physiol 2002; 282 (2): 211-219.

4. Kaunitz JD, Akiba Y. Curr Opin Gastroenterol 2004; 20: 526-532.

5. Ramanathan T, Thirunavukkarasu P, Panneerselvam S, et al. J Pharm Res 2011;4(4): 1167-1168.

6. Wallace JL, McKnight W, Reuter BK, et al. Gastroenterology

2000; 119: 706-714.

7. Berenguer B, Sanchez LM, Quilea A, et al. J of Ethanopharmacol 2006; 77: 1-3.

8. Bembo SA, Carlson HE. Cleveland Clin J Med 2004; 71 (6): 511-517.

9. Ladewig PW, London ML, Davidson MR. Contemporary Maternal-Newborn Nursing Care (6th ed.). New Jersey: Pearson Education, Inc, 2006, pp. 255.

10. Reilly JP. Am J Health- Syst Pharm 1999; 56(23): S11-S17. 11. Dharmani P, Palit G. Indian J Pharmacol 2006, 35; 95-99. 12. Ueda H, Kaneda N, Kawanishi K, et al. Chem Pharm Bull 2002;

50(3): 403–404.

13. Noumi E, Tchakonang NYC. J Ethnopharmacol 2001; 76: 263– 268.

14. Ibara JR, Elion Itou RDG, et al. J Med Sci, 2007;7(3):485-488. 15. Trease E, Evans WC. Pharmacognosy. Williams Charles Evans

(15th ed.). Saunders Publisher London, 2008, pp. 137- 400. 16. OECD. Acute oral toxicity- Acute Toxic Class Method 2010;

1(4):1-4.

17. Ubaka CM, Ukwe CV, Okoye CT, et al. Asian J Med Sci. 2010; 2(2): 40-3.

18. Shokunbi OS, Odetola AA. J Med Plant Res 2008; 2(10): 261-267.

19. Arisawa T, Shibata T, Kamiya Y, et al. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 2006; 33: 628-632.

20. Abdulla MA, AL-Bayaty FH, Younis LT, et al. J Med Plant Res

2010; 4(13): 1253-1259.

21. Bandyopadhyay D, Biswas K, Bhattacharyya M, et al. Curr Mol Med 2001; 1: 501-513.

22. Bandyopadhyay D, Biswas K, Bhattacharyya M, et al. Indian J Exp Biol 2002; 40: 693-705.

23. Ramirez RO, Rao CC. Clin Hemorheol Microcir 2003;29: 253-261

24. Gonzales E, Iglesias I, Carretero E, et al. J Ethanopharmacol

2000; 70: 329-333.

25. Mota KS, Dias GE, Pinto ME, et al. Molecules 2009; 14: 979-1012.

26. Ham M, Kaunitz JD. Curr Opin Gastroenterol 2007;23: 607-616.

27. Toma W, Trigo JR, Bensuaski de Paula AC, et al. J Ethnopharmacol 2004; 95: 345-351.

28. de Sousa Falcão H, Leite JA, Barbosa-Filho JM, et al. Molecules

2008; 12: 3198-3223.

29. Sanchez S, Martiln MJ. Ortiz P, et al. Digest Disea Sci. 2002; 47: 1389-1398.

30. Shetty BV, Arjuman A, Jorapur A, et al. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol 2008; 52(2): 178-182.

31. Swarnakar S, Ganguly K, Kundu P, et al. J Biol Chem 2005; 280: 9409-9415.

*****

© 2013; AIZEON Publishers; All Rights Reserved