THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN CREATIVITY AND PSYCHOSOCIAL DEVELOPMENT AMONG COLLEGE HONORS STUDENTS

AND NON-HONORS STUDENTS

A Dissertation by

AMY ELIZABETH DUPRÉ CASANOVA

Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University

in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY

August 2008

THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN CREATIVITY AND PSYCHOSOCIAL DEVELOPMENT AMONG COLLEGE HONORS STUDENTS

AND NON-HONORS STUDENTS

A Dissertation by

AMY ELIZABETH DUPRÉ CASANOVA

Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University

in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY

Approved by:

Chair of Committee, William R. Nash Committee Members, Joyce E. Juntune

Victor L. Willson Ben D. Welch Head of Department, Michael R. Benz

August 2008

ABSTRACT

The Relationship Between Creativity and Psychosocial Development Among College Honors Students and Non-Honors Students. (August 2008)

Amy Elizabeth Dupré Casanova, B.S., Oklahoma State University; M.S., Oklahoma State University

Chair of Advisory Committee: Dr. William R. Nash

The purpose of this study was to determine if there was a difference in measures of creativity and psychosocial development in college Honors and Non-Honors students and also to determine interaction effects of demographic and academic background data. Additionally, another purpose was to establish any relationship between measures of creativity and psychosocial development. Of the 284 college students participating, 120 were honors students and 164 were non-honors students. Participants were administered the Torrance Tests of Creative Thinking (TTCT) Verbal Form B, Activities 4 and 5 and the Student Development Task and Lifestyle Assessment (SDTLA). The TTCT included scales of fluency, flexibility, originality, and average standard creativity score. The SDTLA includes the measurement of three developmental tasks, ten subtasks, and two scales. The participants were volunteers and were tested in four regularly scheduled classes during the 2006 spring and summer semesters.

Two-tailed independent t-tests performed on the dependent variables of the TTCT indicated that the Non-Honors student’s scores were statistically significantly

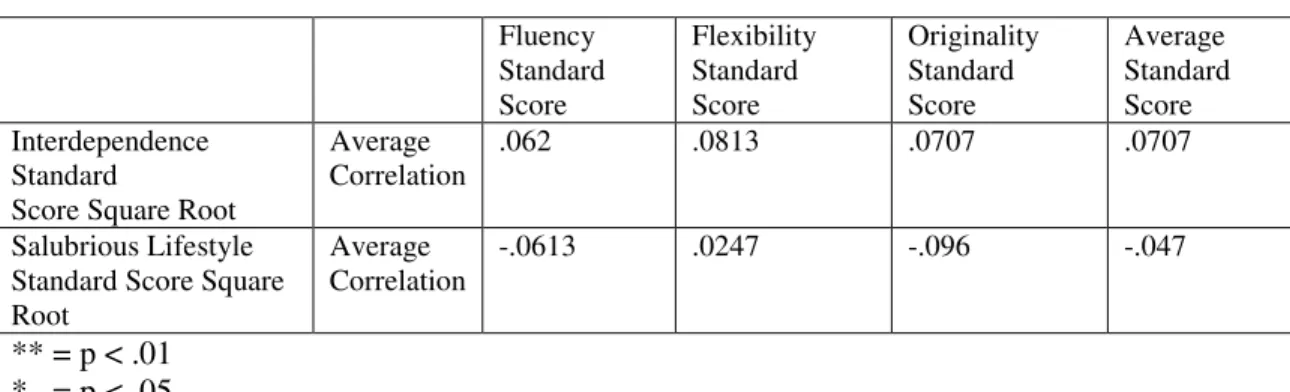

higher on fluency, originality, and the average standard creativity measures. On the average standard score, which is considered the best overall gauge of creative power, neither Non-Honors nor Honors student groups TTCT scores were considered higher than weak (0-16%) (Torrance, 1990). The results of the two-tailed independent t-tests performed on the dependent variables of the SDTLA resulted in the statistically significant higher development outcome scores in the Honors students. The mean SDTLA scores of both the Honors and Non-Honors scores were not outside of norm group average scores. The MANOVA data produced moderately statistically significant interaction effects between classification level and fluency. However, the post hoc tests did not confirm the difference in classification and fluency. Additional MANOVA data indicated a significant interaction effect between ethnicity and Lifestyle Planning (LP), and post hoc analysis confirmed the interaction with significant differences in Caucasian and “Other” students. Classification level significantly interacted with eight of the fourteen development outcomes, nevertheless the post hoc tests showed inconsistent differences between classification groups within the developmental outcomes. Correlations between the TTCT and SDTLA did not yield statistically significant relationships between the creativity and psychosocial development variables.

DEDICATION

I would like to dedicate the completion of this degree to my family, my friends, my dear dog-child, Sully, and my wonderful husband, Mark. You have all helped me achieve the completion of my Ph.D., each in your own immeasurable and special ways.

My friends and family, who were both supportive and understanding of my work, your love and friendship is immensely valued and appreciated. I would not be where I am today, without each of you.

Sully, my dear dog-child, who spent many days helping me work by sitting with me while I was reading and writing – thank you. He helped so much by giving me his unending devotion and love with lots of kisses, snuggles and knowing when I needed breaks to walk around.

Mark, your unwavering cheerleading, support, love, and gentle ways of nudging me to the finish line were some of the main sources of support throughout this process. I do not have the words to begin to express how much you mean to me or how much I love you and my gratitude for all you do is endless.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

First and foremost, I want to acknowledge my advisor, Dr. William Nash. Your support, guidance, and help in both beginning and completing this Ph.D. program and dissertation are greatly appreciated. Thank you for introducing me to and inspiring my interest into the world of creativity. You have helped create another scholar with a great appreciation for the field, to which you have devoted so much. In addition, my

dissertation committee members have been an immense source of guidance and help. Dr. Joyce Juntune lent her expertise in creativity and education, and also provided additional help of the occasional pep talk, practical advice, and excitement about the potential use of my research. Dr. Victor Willson provided valuable time and knowledge of statistical methodology, SPSS, and data analysis. Our interactions always pushed me to learn more and gain confidence in my understanding of statistics and measurement theory. Thank you for believing in my abilities. Dr. Ben Welch provided his expertise and insight into student affairs and honors students, while providing a great deal of support and an unending positive attitude. You all provided significant contributions to the foundation of this research and you each have my utmost respect and heartfelt thanks.

Thanks also go to the department faculty and staff for making my experience at Texas A&M University wonderful. I also want to extend my gratitude to Dr. Peter Wachs, Appalachian State University, and the Scholastic Testing Service, which provided advice, scoring and the testing instruments. Additional appreciation goes to

Dr. Rodney Hill and Dr. Joyce Juntune, who helped greatly with my data collection and to all of the Texas A&M students who were willing to participate in this study.

I want to thank my parents, William E. Dupré and Mary E. Dupré, who always stressed the importance of education and encouraged a love of learning. To my sisters, brothers-in-law, nieces, nephews, and other family members – thank you for your support, kind words and positive thoughts. I am thankful for such a wonderful family.

To my Parents-in-law, Rudy and Del Casanova, thank you for your continual thoughts, concern, and prayers for me in completing this degree. Your kind words and thoughts have been wonderful encouragement. The positive thoughts and words from the rest of the Casanova clan were always appreciated and welcome.

Thank you to my friend, Ms. Penelope Soskin, for your wonderful coaching, support, encouragement, advice and suggestions on how to get my dissertation finished – and thank you for just listening, when I needed to talk. To my friend, Dr. Julie Knoll Rajaratnam, thank you for your advice, listening, and being a sounding board on my writing process and data. I am so glad we met and were able to work together.

Thank you to my many dear and wonderful friends! You all have been so supportive of me in this process and I will never be able to express how much that has meant to me. To my dear, sweet friends, Dr. Laura Mackay and Dr. Lori Broughton – without your support and encouragement, especially during our carpooling drives, I would not be here! We are all finally finished! I owe a great deal to my cousin, David. Thank you for the phone calls, the emails and all of the help you provided. My friends who have gone through a Ph.D. program deserve a special thank you. Thank you for

your help – emotionally and otherwise and for just knowing what the experience is like and what it takes to get through it. Your advice was always sage.

I want to offer a special acknowledgment for Dr. Marcia Dickman, to whom I owe a very special thank you and a great deal of gratitude. You were so much more than just a professor and an advisor, but also a mentor, a friend, and someone I aspire to be like – someone we lost much too soon.

I also owe a great debt and thank you to all of the teachers, coaches, ministers, and other people in my life, who were great sources of inspiration for me – even when I did not know it. You saw something promising in me and helped that promise to grow. All it takes is one person in a child’s life, to make a difference and encourage a life of achievement, greatness, and creativity. Thank you all for being that person in my life.

And finally, I want to thank my husband Mark. You have been my rock and my shoulder when I needed one. You have supported me throughout this ride and been with me nearly every step of the way – if not in person, always in spirit. Thank you for your enduring encouragement and patience. We accomplished this together.

TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ABSTRACT ... iii DEDICATION ... v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ... vi TABLE OF CONTENTS ... ix

LIST OF TABLES ... xii

CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION... 1

Statement of the Problem ... 2

Purpose of the Study ... 4

Research Questions ... 5

Limitations ... 5

Definition of Terms... 6

II REVIEW OF RELATED LITERATURE ... 8

The History of Higher Education ... 8

Psychosocial Development ... 13

College Student Psychosocial Development... 18

Chickering’s Theory of Psychosocial Development... 19

Development Related to Women and Minority Students... 24

Creativity... 29

Definition of Creativity ... 30

Torrance’s Theory of Creativity... 33

Creativity and College Students... 35

Honors Programs... 41

History of Honors Programs ... 42

Current Honors Programs... 45

Selection of Honors Students ... 46

Honors Programs’ Relationship to Giftedness ... 48

Honors Students Compared to Non-Honors Students... 50

CHAPTER Page

Summary of the Literature ... 54

III METHODOLOGY... 56

Participants ... 56

Measures... 58

Torrance Tests of Creative Thinking ... 58

Student Development Task and Lifestyle Assessment ... 60

Additional Academic Background Questions ... 69

Procedure... 70

Data Set Preparation... 72

Analysis of Data ... 75

Summary ... 78

IV RESULTS... 80

Summary of Data ... 80

Study Population and Sample ... 80

Research Question One ... 83

Research Question Two ... 89

Research Question Three ... 98

V SUMMARY, DISCUSSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS ... 102

Summary of Findings ... 102

Research Question One ... 103

Research Question Two ... 105

Research Question Three ... 110

Discussion ... 111

Limitations of the Study... 111

Topics for Future Research ... 113

Synthesis... 115

REFERENCES... 117

APPENDIX A ... 130

APPENDIX B ... 132

Page APPENDIX C ... 133 APPENDIX D ... 134 APPENDIX E... 136 APPENDIX F... 138 VITA ... 139

LIST OF TABLES

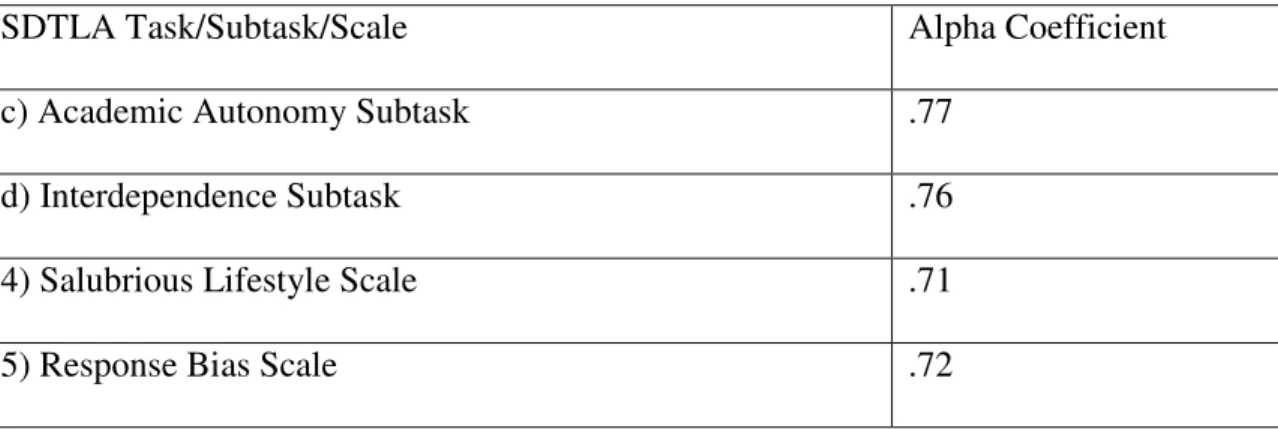

Page Table 1 Student Development Task and Lifestyle Assessment

Reliability Estimates ... 67

Table 2 Participants Demographic Characteristics ... 82

Table 3 Participants Age Frequencies ... 83

Table 4 Fluency t-test Results ... 84

Table 5 Originality t-test Results... 85

Table 6 Average Standard Scores of Creativity t-test Results ... 85

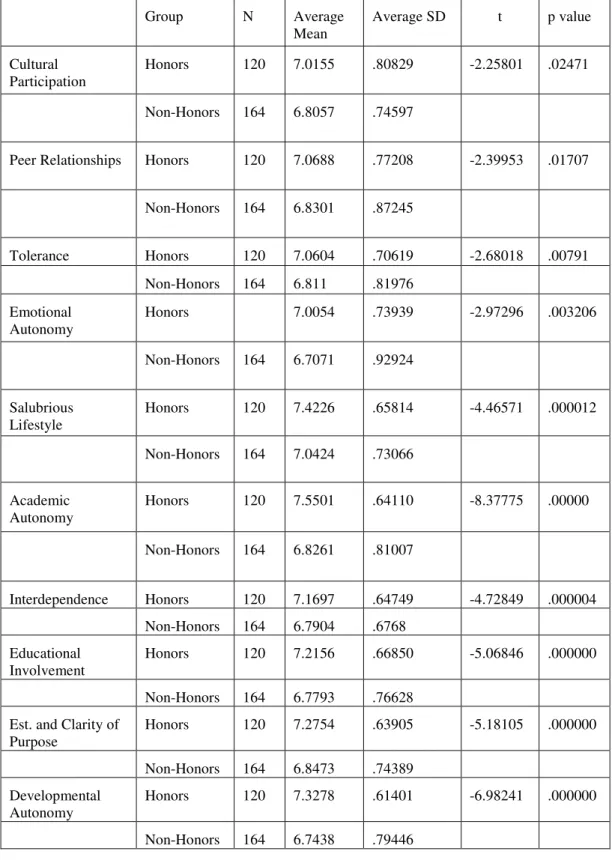

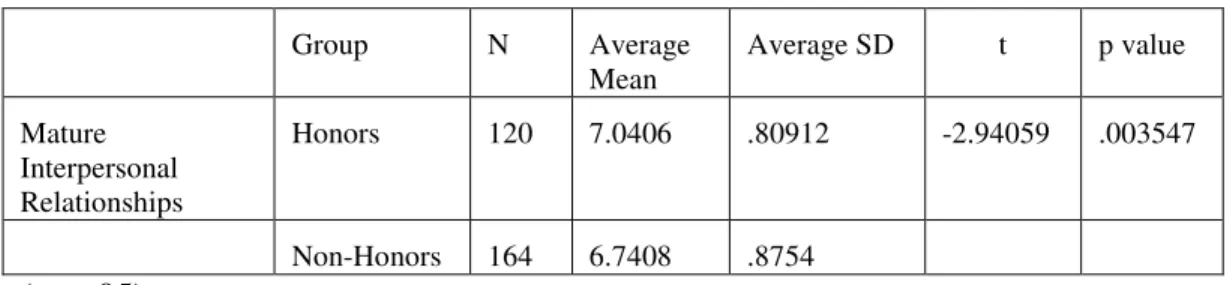

Table 7 SDTLA t-test Results ... 90

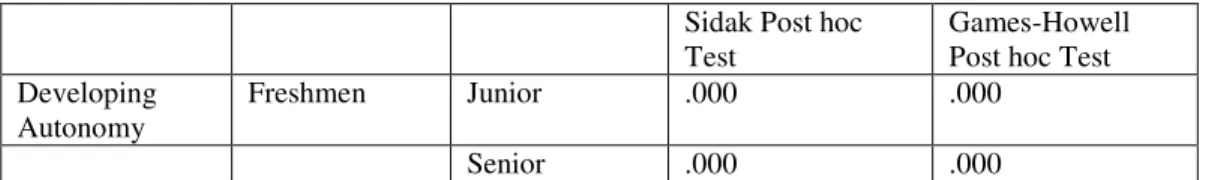

Table 8 Post hoc Tests of Significant Classification Differences ... 96

CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION

Is this the moment in time when leaders in this technically oriented society move forward from valuing a knowledge-based society to valuing creativity? In the past several years several nationally recognized leaders in politics, education and business have focused on innovation and creativity in speaking engagements or writing.

Examples of these are Sir Ken Robinson speaking to the National Governors Association on August 7, 2006, about the importance of creativity in education; John Edwards, former Presidential candidate, in a speech to the National Press Club on June 22, 2006 talking about the necessity of innovation; Lawrence Summers, former Harvard

University President, on This Week with George Stephanopoulos on June 25, 2006 addressing student creativity; the June 19, 2006 edition of Business Week devoting an entire section to creativity and innovation; and on February 6, 2007 Texas Governor Rick Perry mentioned the importance of innovation in his annual State of the State speech.

It would appear that there is an increased awareness of the importance of innovation and creativity in the United States, as evidenced by these newsworthy

examples. America’s leadership in innovation depends on the development, cultivation, and fostering of creativity, which is in large part the responsibility of the education system. However, while “creativity has become the sine qua non of a successful ____________

America (Tepper, 2004, p.B6)” and “nurturing it is seen as an important public good, not only benefiting individuals, but contributing to the economic health and well-being of the country at large (Ibid, p.B6)” creativity is not emphasized in colleges and

universities. In fact, it is taken “for granted that higher education fosters creativity” (Tepper, 2004, p.B6). Often it appears that student’s creativity thrives in spite of their college and university experiences (Douglas, 1991; Tepper, 2004). Cultivating the creativity of college students will continue to be necessary for the U.S. to maintain its place as a leader of innovation.

Statement of the Problem

To begin this discussion, innovation and creativity must be defined. At its most basic level, creativity can be described as generating new and improved ideas, and innovation is described as implementing those ideas into practice (West & Rickards, 1999). While Texas acknowledged the importance of creativity in K-12 education in the 1996 State Plan for the Education Gifted/Talented Students by establishing a goal that “gifted students will demonstrate skills in self-directed learning, thinking, research, and communication as evidenced by the development of innovative products and

performances that reflect individuality and creativity” (Texas Education Agency, 2000, p. 1), it has lagged behind in its commitment to creativity in higher education.

Creativity research focused on college students appears to be minimal. The limited amount of research that has been done indicates that some highly creative college students may not complete college, have academic difficulties in college, or change their

major with higher frequency (Heist, 1968b). This is an interesting finding, since many definitions of giftedness include creativity as an important component. The

establishment of the honors program appears to be the closest thing to a specific program for gifted and talented college students and, by using a portion of the definition from the K-12 education system, creative students.

Because participation in honors programs is based on high achievement

qualifications, and the benefits can include smaller classes, more faculty interaction, and high quality learning experiences, it needs to be assessed as to whether or not honors programs actually produce more creative and psychosocially developed students. Due to the importance of creativity and psychosocial development in higher education, it is crucial that they be analyzed concurrently. The inclusion of honors students is important due to the emphasis many colleges place on honors programs and because of the

assumption that they are the best and brightest of college students. The question remains whether honors students are more creative and have higher levels of psychosocial

development than non-honors students.

In addition to the cultivation of creativity and innovation in college students being recently established as a crucial goal of higher education, the concept of educating the whole student has historically been an important component of higher education’s mission (Nuss, 1996; Rudolph, 1991; Upcraft & Moore, 1990). The development of well-adjusted individuals, who are ready to achieve their goals and make contributions to the world, is a necessity. Another necessary goal of higher education should then be to

encourage the positive psychosocial developmental changes in students (Chickering, 1981).

In response to the public calls for more emphasis on and awareness of innovation and creativity, several questions must be asked, especially in relation to their role in higher education. Does participation in higher education contribute to a creative

society? What role would high achieving students play in this creative society? To what extent are honors programs and creativity related? How does higher education foster psychosocial developmental opportunities?

Purpose of the Study

The purpose of this study was to investigate whether creativity and psychosocial development are different among college honors and non-honors students, while also evaluating the demographic and academic background data for important subgroup relationships. An additional purpose was analyzing the relationship between creativity and psychosocial development, while evaluating interaction effects of the demographic and academic background data. The results of the research provide a better

understanding of creativity and psychosocial development in college students in relationship to their participation in honors programs and whether demographic and academic background information is important to these research constructs.

Additionally, the information gained from this study can be applied to not only honors programs, but also educational settings that aid in fostering creativity and all constituents of higher education.

Research Questions

1. Is there a significant difference between college honors students and non-honors students on creativity scores from the Torrance Tests of Creative Thinking (TTCT) and are there interaction effects based on age, ethnicity, gender, classification, area of major and academic background factors?

2. Is there a significant difference between college honors students and non-honors students on psychosocial development scores from the Student Development Task and Lifestyle Assessment (SDTLA) and are there interaction effects based on age, ethnicity, gender, classification, area of major and academic background factors? 3. Is there a significant relationship between creativity scores and psychosocial

development scores and are there interaction effects based on age, ethnicity, gender, classification, area of major and academic background factors?

Limitations

1. Students who participated in the study are volunteers; and thus selection bias may be present.

2. The power of statistical findings may be limited by the relatively small sample size, particularly within the ethnic and racial sub-groups of students.

3. Because students are designated as Honors or Non-Honors, it was not possible to determine whether a student was eligible for the honors program, but did not participate.

4. If a student was eligible for the honors program but did not participate, and they show high scores on creativity and development assessment, the overall group scores could be skewed.

5. No causal interpretations can be made from these results, if significance is found. 6. Only two sections of the Torrance Tests of Creative Thinking (TTCT) were used.

Definition of Terms

Creativity – “Process of becoming sensitive to problems, deficiencies, gaps in knowledge, missing elements, disharmonies, and so on; identifying the difficulty; searching for solutions, making guesses, or formulating hypotheses about the

deficiencies, testing and retesting these hypotheses and possibly modifying and retesting them; and finally communicating the results” (Torrance, p. 8, 1974).

Psychosocial Development – “A series of developmental tasks or stages, including qualitative changes in thinking, feeling, behaving, valuing, and relating to others and to oneself” (Chickering & Reisser, 1993, p.2).

Honors program – “The total set of ways by which an academic institution

attempts to meet the educational needs of its ablest and most highly motivated students” (Austin, 1975, p160).

Honors Students – Students who are eligible for and are participating in an honors program. Eligible first semester freshmen at Texas A&M University must graduate in the top 10% of their high school class and have a 1250 SAT 1/28 ACT or be a National Merit Finalist, National Achievement Finalist, or National Hispanic Scholar. Second

semester freshmen, sophomores, juniors, and seniors are eligible with a GPR or 3.5 or higher. A 3.5 cumulative GPR is required for continuation in the program (Texas A&M University, 2007).

Non-honors students – Students who are not participating in an honors program. Academic background factors – Characteristics related to measures of academic performance, i.e. area of major, overall college grade point ratio (GPR), SAT/ACT scores, High School rank, Gifted/Talented program participation in High School, and first generation college student.

CHAPTER II

REVIEW OF RELATED LITERATURE

A man searched the known world for the greatest general who ever lived. Unable to fulfill his quest on earth, he ascended to the Pearly Gates. Upon meeting St. Peter, the man said, “I’m looking for the greatest general who ever lived. I have combed the world without success-is such a person here, perhaps?” St. Peter replied, “You are in luck. Just beyond the Gates-over there-is the greatest general who ever lived.” “Wait a minute!” exploded the searcher. “You must be mistaken. I knew that man on earth. He was a humble cobbler-not a general!” “Aha!” rejoined St. Peter. “If he had been given the opportunity and encouragement, he could have been the greatest general who ever lived.” - Mark Twain

The story above, told by MacKinnon (1962) and attributed to Mark Twain, illuminates the importance of not only discovering and recognizing potential talent, but also creating the environment for that talent to flourish and grow. In the current study, it is important to understand what is meant by the term “creativity”, in both a historical and operational context. In addition, it is also important to understand the history and major theoretical orientations of student development as well as honors programs. This will help to provide the context through which the methods and results of this study can be analyzed.

The History of Higher Education

The first forms of formal education are based in ancient Greece and Rome and were intended to assist wealthy men gain positions of power. Since that time, methods of formal education have undergone considerable shifts in organizational theory and focus. Higher education or post-secondary education, as we know it in the United

States, has had a relatively recent birth and has undergone its own changes in philosophy and forms of organization.

A brief history of higher education and the creation of student development theory would be helpful in understanding the basis of student development. As Fenske has stated, “in the beginning was the term in loco parentis” (1989, p. 5). The first colleges in America utilized the mode of operation, in loco parentis. When colleges were first established in early America, all of the staff was expected to act in place of parents, fulfilling the role of the holistic method of education from the traditional English residential university system of the 1700’s, such as Oxford and Cambridge (Thelin, 2003). These Colonial colleges empowered discipline that “was paternalistic, strict, and authoritarian” (Nuss, 1996, p. 24), not to mention a way of life that was “dependent on dormitories, committed to dining halls, permeated by paternalism” (Rudolph, 1991, p. 87). The colleges were typically small, affiliated with a religion, and the faculty and president were responsible for not only the intellectual development, but also the enforcement of student conduct and discipline, as well as moral development of the students (Moore & Upcraft, 1990; Nuss, 1996; Thelin, 2003). This traditional approach to education began in America with the establishment of Harvard in 1636 and continued well into the 1800’s.

Three important developments occurred after the Civil War that contributed to how student development became important in higher education. These included “the shift in emphasis from religious to secular concerns, the expansion of institutions in size and complexity, and the shift in faculty focus from student development to academic

interests” (Fenske, 1989, p. 7). The Morrill Land Grant Act of 1862 gave states the ability to found and develop their own public colleges by providing federal funding. This resulted in increasing the size of college enrollments and making a college education accessible to additional students.

By 1900, nearly all of the states had taken advantage of the landmark law and established state universities. The Morrill Act in 1890 also helped increase college enrollments, by providing public funding and leading to the establishment of Black colleges in seventeen states (Nuss, 1996; Rudolph, 1991). While this legislation increased the opportunities for black students to gain a college education, the “separate but equal” mantra was maintained, thus continuing to limit access to higher education by minority students (Nuss, 1996). This period of time also witnessed increased enrollment of women in higher education, due in part to the establishment of Georgia Female Seminary in 1836 as the first U.S. College for women (Nuss, 1996). The institutions intended for women were typically considered “teachers colleges.” The opening of Vassar College in 1865, initiated a new era for women’s education, as it was the first college to offer a complete curriculum of liberal arts study for women.

Additional changes of educational philosophy and systemic organization in higher education occurred over the next century. The middle 1800’s saw a dramatic shift away from the paternalistic, rules oriented education of the colonial colleges, to a form more closely aligned with the German university emphasizing scholarly research, academic freedom, and the establishment of the professorship (Cowley & Williams, 1991; Nuss, 1996). The Faculty no longer served as disciplinarians for the students and

instead focused solely on research, instruction and intellectual development of the students.

By the early 1900’s, a somewhat more relaxed view of education had been implemented at many U.S. colleges and universities (Nuss, 1996). Extracurricular activities were created, as a result of students opposing strict methods of instruction and demanding organizations in which to participate (Nuss, 1996). Although students persevered in their demands and the administrations eventually acquiesced, college administrators generally opposed these extracurricular organizations (Nuss, 1996). Examples include literary and honor societies, such as Phi Beta Kappa, male and female Greek-letter organizations, and an expansion of athletic activities for students (Nuss, 1996). A new educational movement, the honors program, was also created during this period, although they were located mainly at small private Eastern colleges (Rudolph, 1991).

Until the 1940’s, many colleges were still very small and had limited choices of majors as well as graduate programs. With the implementation of the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act, or the GI Bill, following WWII, a college education became both accessible and available to those who previously did not have that opportunity, dramatically increasing the enrollment numbers of students in institutions of higher education (Nuss, 1996; Thelin, 2003). In fact, the combination of the egalitarian viewpoint along with an expansion of research grants from both government and

which resulted in the unprecedented influence of America’s colleges and universities and lasted from 1945 to 1970 (Thelin, 2003).

The civil unrest of the 1960’s brought about additional changes in higher education. Increased student activism related to both societal issues, e.g., the Civil Rights movement, the Vietnam War, and the draft, in addition to concerns regarding large classes, impersonal treatment by administrators, lack of student housing and limited connections to faculty created an environment ripe for transformation (Thelin, 2003). Federal interventions that helped result in further increasing enrollment,

diversification, and accessibility in colleges were Title IV of the Housing Act in 1950, Vocational Education Act, the Higher Education Facilities Act, the Health Professions Act, the Higher Education Act, Title VI of the Civil rights Act of 1964, Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972, Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, The Drug Free Schools and Communities Act, the Student Right-to-Know and Campus Security Act of 1990, the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990, and the Higher Education Amendments of 1992 (Nuss, 1996; Thelin, 2003). Most of these bills and laws were designed to decrease discrimination in higher education and provide equal access and opportunities in programs and education that received federal monies (Nuss, 1996).

In more recent times, the focus has been on the student as consumer, with more and more emphasis placed on accountability, program evaluation, and outcomes. The federal and state governments have reduced funding for higher education, resulting in increased financial difficulty for colleges and universities, requiring them to “do more

with less” (Thelin, 2003, p. 18). These current pressures, as well as others, on

institutions of higher education, bring to the forefront the importance of several issues investigated in this study.

Psychosocial Development

The increased demand for on-campus student services and having people other than faculty handle student events and activities outside of class, led to the creation of student affairs units on college and university campuses. As a result, the creation of and later, expanded emphasis on student affairs, helped to foster research and understanding of student development. In 1962, the landmark work of Nevitt Sanford was the first investigation of college students through the eyes of behavioral and social scientists (Thelin, 2003). This was the beginning of applying developmental theories to college age individuals. In addition, researchers began viewing the college student as belonging to a separate developmental age group, traditionally perceived to be ages eighteen to twenty-two. As a result, understanding the development of the student over the course of their four years in college became important to all constituents of higher education.

So, why is development important? It is important because most leaders in higher education agree with “the fundamental presuppositions that people can change and that educators and educational environments can facilitate that change” (Miller & Winston, 1990, p. 99). To further this idea, the main “issue is not so much whether the higher education experience promotes growth and development beyond the intellectual domain alone, for there is consensus that it does, but rather what forms that development

takes and how it can be identified and assessed” (Miller & Winston, 1990, p. 100). These models provide a means for understanding and assessing “where students are, where they are going, and how they get there” in terms of their own growth and development” (Strange & King, 1991, p. 16).

There are several types of development that could be considered when discussing student development, i.e. cognitive, psychosocial, moral, physical, etc. In fact, when looking at college student development, it appears that several researchers determined the theories available could be divided into three distinct models. Those investigators have identified the models to be personological, environmental, and person-environment interaction (Widick, Parker, & Knefelkamp, 1978a; Rodgers, 1990b). The

personological model describes the individual differences of students. The environmental model describes the milieu that students’ experience. The person-environment interaction model illustrates the interactions of the student and their environment.

However, other researchers divide student development theories into five categories, including psychosocial, cognitive developmental, maturity, typology, and person-environment interaction (Widick et al., 1978a). Both psychosocial and cognitive developmental theorists give methods of describing where students are developmentally and go on to clarify how developmental changes took place (Widick et al., 1978a). Psychosocial development is defined as a series of developmental tasks or stages, including qualitative changes in thinking, feeling, behaving, valuing, and relating to others and to oneself (Chickering & Reisser, 1993). Cognitive developmental theories

explain the stages involving permanent shifts in certain modes of thinking, perceiving, and reasoning (Widick et al., 1978a). Maturity models of development synthesize developmental models into one inclusive model. Typology theories suggest specific individual differences and characteristics that interact with the process of development (Widick et al., 1978a). Person-environment interaction, which has previously been described, combines the relationship of the student and environment.

This study will focus on theories related to the personological or individual differences model and the psychosocial cluster of student development. Specifically, Chickering’s (1969) original and Chickering and Reisser’s (1993) revisions of the psychosocial development theory will be utilized in the current research.

While several theorists agree as to the existence of developmental crises and movement through stages, there should be some caution in generalizing these

assumptions. As Miller and Winston (1990) note, authorities differ on when and why a particular developmental change will likely occur in a person’s life. One explanation of this disagreement is that development does not take place at exactly the same

chronological time for everyone. Although the research appears to support the idea that “individuals experience common developmental tasks and progress through similar developmental processes and stages, the individual differences involved make it impossible to predict with even reasonable accuracy when a particular individual will face or deal with a particular developmental task, crisis, or stage” (Miller & Winston, 1990, p. 103). These individual differences should be taken into account when looking

at the point in which an individual deals with a certain developmental task, stage or crisis (Creamer, 1990).

When psychologists first began trying to understand the psychological

development of individuals, they tended to focus on adults. Erik Erikson (1968, 1969) was the first to focus on adolescence as a separate developmental age needing its own definitions, with many psychosocial theorists using his research as a building block for further research. In his groundbreaking work, “Childhood and Society” (1969), Erikson proposes that development occurs in stages, with each stage containing specific tasks to be accomplished before moving on to the next stage. Erickson suggests that eight, age-related, sequential stages of development occur over one’s lifetime. Effective or ineffective resolution of the task influences one’s basic orientations or attitudes toward the world (Evans, 1996). The first three stages occur before the age of five: Trust versus Mistrust, Autonomy versus Shame and Doubt, and Initiative versus Guilt. The fourth stage, Industry versus Inferiority, is associated with childhood, typically elementary school age. The fifth and sixth stages, Identity versus Role Confusion and Intimacy versus Isolation are related to adolescence and young adulthood. The seventh stage, Generativity versus Stagnation occurs in middle adulthood and the eighth stage, Integrity versus Despair, arises in late adulthood.

Some of the major underlying assumptions of Erikson’s theory of development are that every individual progresses through the stages at a predetermined rate of readiness, the individual must be ready for progression to the next stage, society seems to expect a certain proper rate and sequence of development, each psychosocial strength

depends on the appropriate development in the proper sequence, and finally each of the parts of development are present before the actual stage takes place (Erikson, 1968, 1969). The conflicts experienced in each developmental stage are considered normal parts of growth.

While Erikson (1968, 1969) created the first developmental theory to address childhood and adolescence, he did not view the years of the typical college student as a separate entity, with its own definitions and developmental crises. Identity confusion and career indecision are significant issues of concern for the adolescent and the main developmental crisis following adolescence concerns intimate relationships. In fact, Erikson states that it is not until adolescence that individuals develop the necessary maturity and physiological, mental, and social growth to experience an identity crisis (1968).

It is possible to apply Erikson’s theory to college age individuals. Students, who are of the traditional college age, are typically going through identity vs. role confusion stage of development, as defined in Erikson’s theory (1968, 1969). The important identity issues are related to experimenting with roles and life-styles, as well as the ability to “make choices and experience the consequences, identify their talents, experience meaningful achievement, and find meaning in their lives” (Rodgers, 1990a, p. 123). Individuals in this stage range from about fourteen to twenty years of age. In addition, if identity issues are not resolved it may be difficult to develop mature intimacy in relationships, which in turn is a prerequisite for coming to a resolution of issues of

generativity versus stagnation, which start in one’s early 40’s. Because Erikson’s work was focused on males, the application to females may be flawed.

College Student Psychosocial Development

Keniston (1970) went on to propose that there was indeed a new stage of

development somewhere between adolescence and adulthood and it was not reserved for a minority of creative individuals who did not have answers to the questions that seem to define adulthood. These questions relate to career choice, life-style and social role, and the relationship to society in general. He called this new stage youth (Keniston, 1970).

While Keniston (1970) agreed with many developmental theorists that

psychological development involves the biological makeup of an individual, he proposed that “psychological development results from a complex interplay of constitutional givens (including the rates and phases of biological maturation) and the changing familial, social, educational, economic and political conditions that constitute the matrix in which children develop” (Keniston, 1970, p. 635). This new stage of development includes themes of constant tension between the self and society, expressed as

ambivalence as well as estrangement and omnipotentiality, a rejection of prescribed roles of society, the beginning of identities specific to youth, and a value on constant movement and change (Keniston, 1970). Keniston does not group all college students into the developmental stage of youth, instead acknowledging that college students may actually be adolescents or young adults ranging in age from eighteen to thirty. Lastly,

Keniston reports that the developmental stage of youth cannot be equated with adopting youthful fashions, behavior, and speech or body movements.

Erikson and Keniston’s work was important to initiate discussion about

developmental stages separate from the development of an adult. Nevitt Sanford (1962) was the first theorist to further separate development into additional segments of time, giving college students their own developmental stage separate from child or adolescent and adult development. Sanford (1962) describes this unique period of development where the college student experiences challenging situations that need new methods of adaptive responses. His theory focused on the freshman college student and did not encompass the entire college experience. College students should be able to “tolerate ambiguity and open-endedness in himself while he is preparing for adult roles,” not rush into adult roles and be patient in waiting for the adult roles to come along (Sanford, 1962, p. 281). Sanford (1962) emphasized the necessity to actually go through the entire developmental process of college, without taking short cuts. Acceptance of the

“student” role and uncertainty about the future, including relationship and career paths are important developmental tasks.

Chickering’s Theory of Psychosocial Development

Arthur Chickering’s (1969) seminal theory of student development is based on the work of Erikson and Sanford, and is one of the most respected and widely used theory describing college students’ development (Taub, 1997). His landmark study of undergraduate students in thirteen small colleges appeared in 1969. Chickering (1969)

expanded on Erikson’s ideas of identity and intimacy, and proposed that the principal concern during the traditional college years is establishing identity.

Chickering explains an assumption in developing the theory was that the

“primary function of higher education is to encourage student development” (Thomas & Chickering, 1984, p. 393). The current research study uses his theory as the basis of psychosocial development because of its focus on college students.

Chickering initially proposed seven vectors of development that contribute to the formation of identity, in 1969. He used Erikson’s view that development occurs in stages, although Chickering calls the stages vectors and he views vectors somewhat differently from stages. A vector has both force and direction, meaning that human development and change incorporates both a direction and a force.

Chickering (1969) and later Chickering and Reisser (1993), go on to explain that the vectors are not hierarchical in nature in that one can move in and out of the vectors during the college years, moving to higher vectors before fully developing a lower vector, as well as regressing to lower vectors to complete the necessary tasks associated with the vector. However, they are developmentally sequential, building on each other and leading to greater complexity, stability and integration. Some competence and progress must have been achieved in the management of emotions and developing autonomy before the establishment of one’s identity can begin (Thomas & Chickering, 1984). The vectors can interact with one another, with students often finding themselves reexamining issues associated with vectors they have previously worked through

accomplished satisfactorily until the earlier vectors have been addressed, with some progress being made. This is different from stage theories, where one stage must be mastered before one can move on to a higher stage.

Chickering does acknowledge that he based his initial theory on traditional age college students, eighteen to twenty-five years old and that additional research is needed regarding the application of his vectors to a wide variety of contexts and other

combinations of students (Thomas & Chickering, 1984). Students move through the vectors at different rates and a student’s cognitive, emotional, and social development are additional factors in the movement along the vectors. It is vital for college students to move through each of the vectors if they are to establish a self-identity (Chickering & Reisser, 1993; Thomas & Chickering, 1984).

It was Chickering’s intention to merge existing evidence and theory into a guide of developmental changes that would establish a conceptual model that could span the continuum from understanding the college student as a developing being to bringing that understanding into educational practice (Widick, Parker, & Knefelkamp, 1978b; Theike, 1994). He wanted to “make information accessible to college and university faculty members so that they would have ways of thinking about how their educational programs could be organized to encourage such development in more systematic and powerful ways” (Thomas & Chickering, 1984, p. 393). The educational environment wields great influence that helps in moving students through the seven developmental vectors. That influence is generated through many structural factors such as clarity of “institutional objectives, institutional size, faculty-student interaction, curriculum,

teaching practices, diverse student communities, and student affairs programs and services” (Evans, 1996, p. 169; Theike, 1994, p. 5).

The original seven vectors from 1969 included: 1) developing competence, 2) managing emotions, 3) developing autonomy, 4) establishing identity, 5) freeing interpersonal relationships, 6) developing purpose, and 7) developing integrity.

Typically, freshmen will be working through the first three vectors. While sophomores and juniors are most involved in the stage of “establishing identity,” seniors are

commonly facing the last three stages or vectors.

Between 1969 and 1993, it became apparent through additional research with women and ethnic minority students’ that some revisions of Chickering’s theory needed to take place. The theory was subsequently revised in 1993, in order to incorporate new research findings and be more inclusive of various student populations, such as women students, ethnic minority students, lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender students (LGBTA) (Chickering & Reisser, 1993). Chickering and Reisser found that some of the vectors actually needed to be altered somewhat and rearranged, due to changes in

diversity of university populations as well as recent research. Following the revisions of Chickering and Reisser (1993), summaries of the seven amended vectors are:

1. Developing Competence – this vector concerns developing competence and confidence in intellectual, interpersonal, and physical and manual abilities.

2. Managing Emotions – this vector concerns developing the ability to acknowledge and accept, as well as to appropriately express and

manage a full range of emotions, including what are commonly thought of as positive and negative emotions.

3. Moving Through Autonomy Toward Interdependence – this vector involves becoming relatively self-sufficient, responsible in achieving goals, and decreasing others influence of opinions. In addition, increased emotional independence, self-direction, problem-solving ability, persistence, mobility, in addition to the recognition and acceptance of the importance of interdependence are important components of this vector.

4. Developing Mature Interpersonal Relationships – this vector concerns developing tolerance and appreciation of individual differences, and the capacity for developing healthy and lasting intimacy in

relationships.

5. Establishing Identity – this vector depends in part on the previous vectors. It concerns developing a positive self-identity, while acknowledging differences in others related to gender, ethnicity, and sexual orientation. Self-identity includes 1) comfort with the physical body and appearance; 2) comfort with gender and sexual orientation; 3) a sense of self in social and cultural heritage; 4) a clear sense of self with one’s roles and lifestyle; 5) a sense of self, respective of feedback

from significant others; 6) self-acceptance and self-esteem; and 7) personal stability and unification.

6. Developing Purpose – this vector requires creating clear plans and priorities for integrating vocational and career goals, personal interests and activities, and establishing strong commitments with family and other interpersonal relationships.

7. Developing Integrity – this vector is a progression from

uncompromising beliefs to a more humanized, personalized value system respectful and acknowledging of others beliefs, and finally moving to congruence of individual values and socially responsible behavior. (Chickering & Reisser, 1993)

Development Related to Women and Minority Students

The resulting revisions to the theory, as previously noted, were due to the review and evaluation of research, especially related to the development of women and ethnic minority students. Initially, Chickering and Erikson (1993) thought that women simply had a difference in developmental patterns because they “confused identity with

intimacy” (p. 23). Two studies critiqued Chickering’s theories within the context of female students and found significant differences in that women students need longer to resolve issues of autonomy (Straub, 1987; Straub & Rodgers 1986). In addition, Straub (1987) found that women and men develop autonomy differently. For women,

developing autonomy depends on how well they accomplish the freeing interpersonal relationship tasks.

In addition to the previous criticisms, Taub (1997) indicated that even in the 1993 revision of his theory, Chickering did not address the limitations of his theory in relation to women. Taub (1997) goes on to caution graduate programs and student affairs practitioners about the limitations of Chickering’s theory, in light of new and emerging research in how the development of autonomy is applied to female students. Part of her discrepancy with Chickering’s theory is that female student’s close

relationship with their family does not necessarily indicate problems with autonomy. However, like all research, this may not be absolutely accurate, as all female students do not have a close relationship with their family and each relationship is dependent on the context and makeup of the family. Straub and Rodgers (1986) go on to limit the

alternative explanation of female student’s differences in the development of autonomy by finding that those differences depend on sex role orientation, with female students described as androgynous or masculine following Chickering’s timeline for autonomy development and female students described as feminine or undifferentiated score lower on independence and autonomy scales.

Straub (1987) goes even further stating there is more than one way to develop autonomy and suggested that women might need to develop autonomy in their

relationships before they develop autonomy as a whole. So it seems that, according to several research studies, for some women the progress of development in autonomy depends on how they master developing the relationship task. Foubert, Nixon, Sisson,

and Barnes (2005) found female students to be more tolerant than their male peers, at the beginning of college and also throughout their college career. They also found female students to be more developmentally advanced in the mature interpersonal relationships vector, confirming prior research (Foubert, et al., 2005; Utterback, Spooner, Barbieri, & Fox, 1995; Greeley & Tinsley, 1988).

Josselson (1987) conducted additional research focused on female identity development. This research helped confirm that identity development was different for women and men. The women studied had a tendency to maintain connections to their family of origin, while they were forming and living their identities, whereas the men tended to separate from their family of origin. In addition, these women and men placed importance on different issues. The men tended to focus on issues such as religion, politics, and career while separating from their family. The women, on the other hand, were focused on sexual behavior, whom and when to marry, who to be friends with, and religious traditions, during this same time period (Rodgers, 1990b). As cited by Gilson (1990), Gilligan described identity development as “based on the creation and

maintenance of relationships, rather than on the abstractions of commitment, justice, and autonomy hypothesized by Perry, Kohlberg, and Chickering” (p.6). The importance of understanding the potential developmental differences in men and women college students is apparent, especially when it has been ascertained that from 1990 to 2001, women have become a majority of the students enrolled at many colleges, both public and private (Thelin, 2003).

It is widely known that many research studies of college student development, utilized mainly White, middle-class males as participants, especially those studies conducted in the early years of research. While there is an increasing amount of research related to students of color and psychosocial development, many studies have focused on either African American or International students. The amount of research with Latino American, Asian American and Native American College students is still very much lacking. Chickering and Reisser (1993) acknowledged this disparity and used recent studies, with students of color, as resources in revising the theory.

In addition to women, differences in development have also been found in ethnic minority student populations regarding Chickering’s theory of development. Pope (2000) discovered that there is a relationship between racial identity and psychosocial development and suggests that these students are using energy to develop their racial identity, sometimes at the detriment of focusing on their psychosocial development. Pope (2000) also found that within the racial groups of Black American, Asian

American, and Latino American students there were differences in the Establishing and Clarifying Purpose vector, with Black American and Latino American students scoring higher than Asian American students.

Branch-Simpson (1984) specifically studied the development of Black students and compared the results to Chickering’s vectors. While there were some similarities in Black students’ psychosocial developmental tasks when compared to Chickering’s vectors, there were differences in the development of Autonomy and Interpersonal Relationships. The Black students had a greater need to remain connected to their

family and other supportive people, than the students in Chickering’s research. This impacted the Black student’s development of Autonomy, but through their relationships with extended family members and their religious affiliation, Identity was achieved. Another important factor in Establishing Identity was the importance of having role models, comprised of either family members or prominent Black citizens (Rodgers, 1990b).

As previously stated, research regarding Chickering’s theory and other non-white student population’s is very limited. This lack of research should be addressed and studies conducted specifically with these student sub-groups. While Cass (1979) completed further research regarding the psychosocial development of the gay, lesbian, and bisexual college student populations, it is beyond the scope of the current study and therefore will not be addressed in an in-depth manner.

The research and references available about first generation college students and their experiences with psychosocial development is also extremely limited. The first generation college students appear to have lower persistence and graduation rates, than other students. Pike and Kuh (2005) studied how certain experiences affect the

intellectual development and learning of first-generation and second-generation college students. They found that the lack of several aspects of the college experience

negatively affect the success of the first-generation students. These aspects include a lower likelihood of living on-campus, a lack of strong relationships with faculty and other students, as well as lower levels of involvement in campus organizations and clubs. Overall these students were less engaged in college experiences (Pike & Kuh, 2005).

More research is needed to specifically assess the psychosocial development of first-generation college students. The current study attempts to address a portion of the gap in literature.

Since the creation of Chickering’s seminal work in 1969 and the subsequent revision by Chickering and Reisser in 1993, there has been criticism of the theory. In evaluating the developmental theory of Chickering, Foubert, et al. (2005) found Chickering and Reisser’s description of the vectors sequential nature, may need reconsideration. Additionally, Foubert, et al. (2005) indicate “development is not so much a series of steps or building blocks, but rather could be conceptualized differently, like horizontal movement along several rows of an abacus, where development is triggered by environmental factors” (p. 469-470).

Creativity

With innovation receiving so much attention in all levels of education, including higher education, it would seem that creativity would receive the same attention. Creativity is a vital component of innovation, and as such, would appear to be a vital component of higher education. Bruner (1962) states that in preparing for the future, we must encourage creativity in children and students, because it is more difficult than ever before to define the future.

Definition of Creativity

However, creativity is somewhat difficult to characterize, as there is still no agreement as to an accurate method of assessing or defining creativity. With much dissent as to the definition of creativity, understanding the literature available can be difficult. Part of the lack of agreement is due to the many different theoretical models about creative behavior.

Runco (2004) reviewed the literature on creativity and found that the research on creativity is diverse, can be organized in several different ways, and includes numerous and diverse applications. To add to the difficulty of defining and understanding, there appear to be seven methods of studying creativity (Morgan, Ponticell & Gordon, 2000; Plucker, Beghetto & Dow, 2004; Sternberg & Lubart, 1996). For example, MacKinnon (1962) described four strands that are used to categorize creativity research and Rhodes (1961) goes on to state that those four strands are actually intertwined.

Altman (1999) describes characteristics of creative individuals as a greater degree of personal openness, an internal locus of self-evaluation, perseverance, a tolerance for ambiguity, and a tendency toward abstract thought. Sternberg and Lubart (1996) define creativity as the capacity for producing both novel and appropriate work. Runco (2004) describes a change in direction of researching creativity, from a focus on creativity and intelligence or creativity and personality, to a rather broad and diverse breadth of research approaches related to creativity.

In addition to the multiple definitions and categories of the definition of creativity it has been proposed that there are six main methodologies used to study

creativity. The six main approaches used to study creativity include mystical,

pragmatism, psychoanalytic, psychometric, cognitive, and social-personality (Morgan et al., 2000; Plucker et al., 2004; Sternberg & Lubart, 1996). These same researchers suggest that these six methodologies are also roadblocks to the study of creativity. There is also some support in the literature that these roadblocks actually exist and are a

negative effect on creativity research (Sternberg & Lubart, 1996; Treffinger, Isaksen, & Dorval, 1996). However, Plucker et al. (2004) go on to suggest that little has been done to alleviate the roadblocks and that in fact they may contribute to the abundance of faulty beliefs about creativity and in turn limit the study and application of creativity research. Research in creativity can be categorized in an additional manner. Runco (2004)

described a disciplinary framework, “organized by behavioral, biological, clinical, cognitive, developmental, historiometric, organizational, psychometric, and social perspectives” (p. 663-664).

Guilford, in his 1950 address to the American Psychological Association, described a vast failure to study the area of creativity. Some reasons for this neglect are difficulty in measuring creativity and an overemphasis on the study of learning and intelligence. Some of the reasons he gives for studying creativity have been mentioned previously in this study, the economic value of new ideas and the need for visionary leaders. He goes on to initially propose eight areas of divergent thinking or creativity and acknowledges there are different types of creative abilities, but focuses his

hypothesis of creative abilities on scientists and inventors. These eight areas of creative abilities are: 1) sensitivity to problems, 2) fluency, 3) novelty, 4) flexibility of mind, 5)

analyzing ability, 6) reorganizing or redefinition of currently existing ideas, 7) degree of complexity, and 8) evaluation of ideas.

In 1962 MacKinnon proposed that clarity develops when researchers use one or more of four perspectives in which to operationally define creativity: personality, process, press (situation, context or environment), or product. In this context person is used to describe any information about the individual, such as personality, abilities, and behavior. The term process is applied to motivation, learning, perceiving, thinking and communicating and involves the processes individuals use in being creative (Rhodes, 1961). Press is described as how an individual relates to their environment and in turn that creativity results when certain kinds of forces impact a certain kind of person when they are growing up and developing. Product is described as the outcome of being creative, whether it is an idea, theory, invention, or artifact. All four perspectives are considered creative in nature.

Following Guilford’s 1950 address to the American Psychological Association, according to Rhodes (1961), there was a surge of interest in researching creativity. Rhodes (1961) evaluated creativity research and found that there were 40 different definitions for the concept of creativity and that the definitions fell into the four categories, or four P’s of creativity, described by MacKinnon (1962). In addition, Rhodes proposed that these four P’s overlap, are intertwined and only in the unity and intertwining does creativity occur. This is perhaps the most common structure in studying creativity (Runco, 2004).

Torrance’s Theory of Creativity

E. Paul Torrance also acknowledged the four Ps, (Rhodes, 1961) person, process, product, and press as different ways in which to view the development of creativity. Torrance subscribes to the process focus of creativity, due to his emphasis on the process of “learning, thinking, teaching, problem-solving, creative, development and other processes – even the personality processes” (Torrance, 1993, p. 232). He describes creativity “as the process of sensing difficulties, problems, gaps in information, missing elements, something askew; making guesses and formulating hypotheses about these deficiencies; evaluating and testing these guesses and hypotheses; possibly revising and retesting them; and, last, communicating the results” (Torrance, 1993, p. 233). In addition, Torrance elaborates on his choice of using the process focus of researching creativity, because ultimately the other three areas of personality, product, and press must be addressed within the process method. This goes against some of the criticism of Torrance’s creativity research, that there must be an integrated method of studying creativity. Torrance described these methods long before it was popular.

Torrance developed a method of identifying creative potential making it possible to conduct research with everyday people, using “relatively simple verbal and figural tasks that involve divergent thinking plus other problem-solving skills” (Sternberg & Lubart, 1996, p. 680). He believed that creativity occurred in the domain of everyday life and is not limited to examples of extraordinary talent. Torrance’s definition of creativity can be grouped in the psychometric category of studying creativity. According to Torrance (1995), the tasks involved in the Torrance Tests of Creative

Thinking (TTCT) are “based on a rationale developed from some research finding concerning the nature of the creative process, the creative personality, or the conditions necessary for creative achievement” (p. 90).

Torrance (1995) designed the tasks that make up the TTCT in order to include “as many different aspects of verbal creative functioning as possible” (p. 90). The tasks of the TTCT are evaluated and then quantified for fluency, flexibility, originality, and elaboration (Torrance, 1974, 1995). Fluency is described as the number of related or relevant ideas. Flexibility is the number of different categories or the number of changes in thinking into which the responses can be placed. Originality is the number of

statistically infrequent responses that vary from the obvious or common answers and “show creative intellectual energy” (Torrance, 1995, p. 90). Elaboration is described as the amount of detail or number of different ideas in the details of an idea (Torrance, 1995).

There have also been criticisms of this psychometric method of studying creativity. Sternberg and Lubart (1996) argued that the brief instrument is not an adequate measure of creativity. Amabile (1983) criticizes this method of studying creativity because fluency, flexibility, originality and elaboration do not represent the true nature of creativity. However, even with these arguments against Torrance’s methods and theories, the Torrance Tests of Creative Thinking is one of the most widely used instruments used to evaluate divergent thinking.

Kirton (1976) offers yet another theory of styles of creativity. He posits that there is actually a cognitive continuum of creativity, with innovators on one end and

adaptors on the other end. Innovators tend to create through working outside traditional systems and produce ideas that are outside of that system or paradigm. Adaptors, on the other hand, tend to work within a system or paradigm in order to improve it and the result is creativity. Kirton (1976) describes that within the continuum of innovators and adaptors; there can be both high and low creative individuals.

Creativity and College Students

There appears to be a gap in both research on creativity and creativity itself, in higher education. There has been a great deal of interest in creativity in children, with less interest in adolescents and still less interest in adults. In fact there have been several studies investigating this lack of creativity in higher education. A review of the literature indicates that research with college students and creativity appears to be minimal. There was only one book available that was specifically related to creative college students, and it was published in 1968. Another important aspect of this limited amount of

research is that while it appears to be quite antiquated, due to the year it was published, it seems to be prescient in how it describes the current state of higher education. It appears that the same issues and dilemmas are still present forty years later. The limited research that has been done specifically related to college students and creativity, indicate that some highly creative college students may not complete college, have academic difficulties in college, or change their major with higher frequency (Heist, 1968b).

Several studies look at creativity related to academic performance, divergent thinking skills, critical thinking skills or cognitive development. A brief review of the

literature on creativity and college students indicates that many of the available research can be placed into four categories: critical thinking skills, divergent thinking skills, personal traits and academic success or achievement.

Shallcross and Gawienowski (1989) described a symposium with over 400 creativity researchers present. Several ideas regarding gaps in creativity and higher education were discussed. They included a concern about how to measure creativity accurately in college students, the fact that the general public needs to understand the relationship between cultivating creative potential and promoting national

competitiveness and enhancing national prestige, the fact that academic achievement does not equate creativity, and finally that promoting creative thinking is an important function of any institution of higher learning.

Soriano de Alencar (2001) described several obstacles that college students face in expressing creativity. She found that students expressed a need for the time and opportunity to be creative. In addition, students reported that they would be “more creative if the educational context would be more appropriate for the nurturance of creativity, as well as if they have had more opportunities to express their potential, more resources to realize their ideas, and if they have received more recognition for the creative work” (Soriano de Alencar, 2001, p. 138). Freedom and supportive academic environments are important for creativity to flourish (Soriano de Alencar, 2001; Barron, 1997; Cole, Sugioka & Yamagata-Lynch, 1999).

Even in 1968, MacKinnon was reporting that the best predictor of creative achievement in college is creative achievement in high school. He goes on to lament