AJR 2006; 187:282–287 0361–803X/06/1872–282 © American Roentgen Ray Society

M E D I C A L I M A G I N G A C E N T U R Y O F Consent Guidelines and Practices

Diagnostic CT Scans:

Institutional Informed Consent

Guidelines and Practices at

Academic Medical Centers

Christoph I. Lee1

Harry V. Flaster1

Andrew H. Haims1

Edward P. Monico2

Howard P. Forman1,2,3

Lee CI, Flaster HV, Haims AH, Monico EP, Forman HP

Keywords: cancer, CT, informed consent, radiation dose, radiation risk, radiology practice

DOI:10.2214/AJR.05.0813

Received May 13, 2005; accepted after revision June 28, 2005.

1Department of Diagnostic Radiology, Yale University

School of Medicine 333 Cedar Street, TE-2, New Haven, CT 06510. Address correspondence to H. P. Forman (howard.forman@yale.edu).

2Department of Surgery, Division of Emergency Medicine,

Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, CT.

3Also affiliated with Yale School of Management, Yale

College Department of Economics, and Yale School of Public Health, New Haven, CT.

OBJECTIVE. The purpose of this article is to characterize current informed consent prac-tices for diagnostic CT scans at U.S. academic medical centers.

MATERIALS AND METHODS. We surveyed 113 radiology chairpersons associated with U.S. academic medical centers using a survey approved by our institutional review board. The need for informed consent for this study was waived. Chairpersons were asked if their institutions have guidelines for nonemergent CT scans (by whom; oral and/or written), if patients are informed of the purpose of their scans (by whom), what specific risks are outlined (allergic reaction, radiation risk and dose, others; by whom), and if patients are informed of alternatives to CT.

RESULTS. The study response rate was 81% (91/113). Of the respondents, two thirds (60/90) currently have guidelines for informed consent regarding CT scans. Radiology tech-nologists were most likely to inform patients about CT (38/60, 63%) and possible risks (52/91, 57%), whereas ordering physicians were most likely to inform patients about CT’s purpose (37/66, 56%). Fifty-two percent (30/58) of sites provided verbal information and 5% (3/58) provided information in written form. Possible allergic reaction to dye was explained at 84% (76/91) of sites, and possible radiation risk was explained at 15% (14/91) of sites. Nine percent (8/88) of sites informed patients of alternatives to CT.

CONCLUSION. Radiology technologists are more likely to inform patients about CT and associated risks than their physician counterparts. Although most academic medical centers currently have guidelines for informed consent regarding CT, only a minority of institutions in-form patients about possible radiation risks and alternatives to CT.

he increasing demand for CT ex-aminations for diagnostic and screening purposes [1–3] has re-newed interest in the issue of radi-ation dose and informed consent. As larger numbers of the population undergo CT screening procedures of uncertain benefit and the number of inpatient studies continues to grow with the introduction of newer applica-tions [4, 5], the subsequent increase in radia-tion-associated cancer risk has become a pub-lic health popub-licy concern [6, 7].

The organ doses from CT examinations are generally higher than those of conven-tional radiographs [8], and the effective doses from CT scans are within the range perienced by atomic bomb survivors who ex-perienced a small but statistically significant increase in solid cancer risk [9] and cancer mortality [10]. More recently, studies have supported an increased lifetime cancer risk among the pediatric population undergoing diagnostic CT scans [11, 12] and adults

un-dergoing elective full-body CT screenings [13]. In January 2005, the National Toxicol-ogy Program of the National Institutes of Health acted to permanently categorize radi-ation as a known human carcinogen [14].

Of particular interest to those in the field of radiology are the ethical and legal implica-tions of increased CT use and the purported increased cancer risks. The fundamental prin-ciple of informed consent states that patients should be provided sufficient information, in a manner that they can understand, to make an informed decision about their care [15]. Such disclosure must include the benefits, the pos-sible risks of the procedure, and the alterna-tives—including foregoing the CT scan alto-gether—to be considered a complete informed consent [16].

To date, informed consent for radiation dose and possible associated risks have not been examined in great detail in the medical literature. Past studies examining informed consent for IV contrast media have

eluci-T

dated a desire among patients to be educated about medical issues such that they may par-ticipate as partners in medical decisions [17–19]. It has been argued that informed consent should be obtained from all patients to provide them with correct information about the radiation exposure and lifetime cancer risk as they are currently understood to respect patient autonomy [20–22].

The purpose of this study was to charac-terize the current informed consent practices for diagnostic CT scans at U.S. academic medical centers, including whether disclo-sure of possible radiation risks is a standard part of informed consent procedures, and to identify who is best positioned to obtain such informed consent. We hypothesized that most academic medical centers cur-rently do not have guidelines regarding in-formed consent for diagnostic CT scans, and that patients, while being informed of possi-ble reactions to contrast dye by a technolo-gist, are not informed of radiation exposure, possible lifetime cancer risks, and alterna-tives to CT scans.

Materials and Methods Participants

We developed a one-page survey that was dis-tributed to all 113 members of the Society of Chairmen of Academic Radiology Departments (SCARD) residing in the United States. The sur-vey was accompanied by a cover letter inviting the subjects’ participation in this study with a descrip-tion of the study goals and assurance of anonymity in the reporting of study data. Both the cover letter and questionnaire were approved by our institu-tion’s institutional review board, and participant informed consent was waived because no patient data were to be collected.

The cover letter and survey were first distrib-uted electronically to the 113 U.S. SCARD mem-bers during the last week of October 2004. The electronic mailing was followed up with a postal mailing 1 week later to all invited participants who had not responded. Participants were given 3 weeks to complete the survey and return it via electronic mail or a self-addressed stamped enve-lope provided in the regular mailing. Finally, all participants who had not returned their surveys by the first week of December 2004 were contacted by telephone to ensure they had received and re-viewed the study material, and to minimize the amount of data lost to follow-up.

Institutional Guidelines

Study participants were asked several multi-part questions and given a selection of check-box

answers and blank space to write their own an-swers. First, department chairpersons were asked if their institution currently has guidelines for in-forming patients (who are not in an emergent, life-threatening state) about the nature of their di-agnostic CT scan before it is administered. An-swer choices included yes, no, and I don’t know. If answering yes, participants were asked who in their institution usually provides the patient infor-mation about the nature of their CT scan. Answer choices included the ordering physician, radiolo-gist, radiology technoloradiolo-gist, I don’t know, and a space for other answers. Institutions with current guidelines were also asked by what method their patients are informed about their CT scans. An-swer choices included oral, written, both oral and written, and I don’t know.

CT Scan Purpose

Second, study participants were asked if patients at their institution (who are not in an emergent, life-threatening state) are informed of the purpose of the CT scan before it is administered. Answer choices included yes, no, and I don’t know. If answering yes, participants were asked by whom patients are informed about the nature of their CT scan. Answer choices included the ordering physician, radiolo-gist, radiology technoloradiolo-gist, I don’t know, and a space for other answers.

CT Scan Risks

Third, study participants were asked which specific risks are outlined to patients pending CT scan for the evaluation of a nonemergent condi-tion. Participants were asked to check all answers that applied. Answer choices included possible allergic reaction to contrast dye, possible radia-tion risk from the procedure, the menradia-tion of ac-tual radiation dose, I don’t know, and a space for other answers. If any specific risks were outlined, study participants were asked who in their insti-tution usually provides the patient information about the risks of their CT scan. Answer choices included the ordering physician, radiologist, radi-ology technologist, I don’t know, and a space for other answers.

CT Scan Alternatives

Finally, study participants were asked if their in-stitution informed patients pending CT scan for the evaluation of a nonemergent condition of alterna-tives to the CT scan before it is administered. An-swer choices included yes, no, and I don’t know. If answering yes, participants were asked by what method patients are informed about the nature of their CT scan. Answer choices included the order-ing physician, radiologist, radiology technologist, I don’t know, and a space for other answers.

Data Analysis

Completed survey data also included geographic information and data regarding affiliation with a public or private university. All data were stripped of personal identifiers before analysis by the study team. Given that the data were descriptive in nature and initial chi-square test analyses yielded no statis-tical significance, further statisstatis-tical analyses were unnecessary and all results are reported here in a purely descriptive manner. Because participants were able to select more than one answer choice for several questions, the final percentage response was greater than 100% for some items.

Results Participants

Completed surveys were returned by 91 chairmen with an overall response rate of 81% (91/113). Of the institutions that partici-pated, 48% (44/91) are affiliated with a public university and 52% (47/91) are affiliated with a private university. Forty-one percent (37/91) of the academic medical centers were located in the Northeast region of the United States, with the second-highest percentage (26%, 24/91) representing the Midwest/Central re-gion of the country (Tables 1 and 2). Institutional Guidelines

Nearly two thirds (60/90) of the respon-dents reported that their institutions currently have overall guidelines for informing patients considering having a CT scan for the evalua-tion of a nonemergent condievalua-tion about their scan before it is administered. At the medical

TABLE 1: Affiliation of Academic Medical Centers

Public or Private

Medical Center Number %

Public 44 48.4

Private 47 51.6

Total 91 100.0

TABLE 2: Academic Medical Centers by Region

Region Medical

Center Located Number %

Northeast 37 40.7

Southeast 18 19.8

Midwest/Central 24 26.4

West/Southwest 12 13.2

Total 91 100.0

centers that reported they have such guide-lines, the radiology technologist (42%, 38/60) was most likely to provide the patient with in-formation about the nature of the CT scan, followed by the ordering physician (21%, 19/60), and then the attending radiologist (15%, 14/60). Other sources of information for the patient regarding the nature of a CT scan included nurses, residents, and clerical staff (Tables 3 and 4).

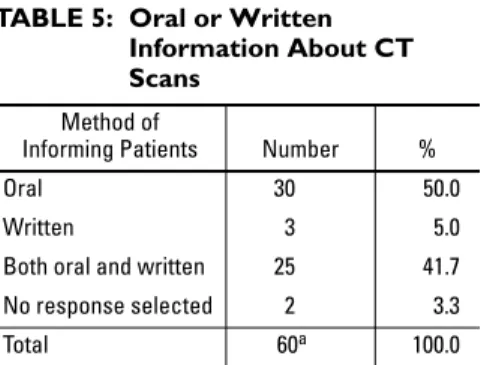

Of the academic medical centers that re-ported they have overall guidelines for in-forming patients about CT scans, 50% (30/60) provided the information verbally and 42% (25/60) provided the information in both written and verbal formats. Three sites (5%) provided patients with written infor-mation only. Two of the sites that reported their institutions have guidelines for provid-ing patients with information did not re-spond to this item (Table 5).

CT Scan Purpose

Sixty-six of 91 (73%) academic medical centers reported they regularly inform patients about the purpose of their CT scans. Five re-spondents reported they did notknow whether patients are informed of the purpose of their CT scans, and one survey participant chose not

to respond to this item. Of the centers that do inform patients regarding the purpose of their CT scans (66/91), 56% (37/66) reported that the ordering physician usually informs patients about the purpose of CT scans and 53% (35/66) reported that the radiology technolo-gist usually serves this role (Table 6). Four medical centers reported that a resident or fel-low usually performs this task, and two centers reported that nurses usually perform this task. CT Scan Risks

Most (84%, 76/91) responding academic medical centers informed patients about the risk of possible allergic reactions to contrast material before administering it for CT scans. In comparison, only 15% (14/91) informed pa-tients about possible radiation risks from the CT scans, and only one site (1.1%, 1/91) men-tioned the actual radiation dose to patients. Five respondents did not know which risks were out-lined to patients, and three academic medical centers did not outline any risks to patients. Other risks of CT that were explained to tients included radiation risks to pregnant pa-tients and risk of nephrotoxicity. Of the centers that provide risk-related information to pa-tients, radiology technologists were the most likely source of this information, followed by attending radiologists. Others involved in ex-plaining risks to patients included nurses, resi-dents, and ordering physicians (Tables 7 and 8). CT Scan Alternatives

Sixty-five of 88 (74%) responding aca-demic medical centers do not inform patients of possible alternatives to CT scans before their administration. Only eight of 88 centers (9%) routinely inform patients of alternatives to CT scans. Fifteen of 88 respondents (17%) did not know whether their medical center in-formed patients of diagnostic alternatives, and three respondents did not respond to this item (Table 9). Of the eight sites that provide patients with information regarding alterna-tives to CT scans, four of eight (50%) respon-dents reported the ordering physician pro-vides patients with such information. Three of eight centers (38%) reported the radiologist provides patients with information regarding alternatives to CT, and one of eight centers (13%) identified the radiology technologist as the source of this information.

Discussion Institutional Guidelines

Two thirds of academic medical centers that replied to our survey currently have

in-stitutional guidelines for informing patients about diagnostic CT scans. We were sur-prised by this majority finding, because in-formed consent for diagnostic CT scans is still heavily debated. Although widespread agreement exists in the radiology commu-nity regarding obtaining informed consent for interventional procedures [23], no such documented agreement is found regarding noninterventional services. This study find-ing was also heartenfind-ing, given that one esti-mate purports that nearly 30% of tests in-volving ionizing radiation are inappropriate, with long-term risks outweighing acute benefits [21].

Although the United States has no current national guidelines for informing patients about radiation exposure with diagnostic CT scans, the European Union has codified into law the requirement that all CT dose informa-tion accompany electronically stored image data for patients and that anyone referring a patient for a radiologic examination must pro-vide “sufficient medical data” to justify the study [24, 25]. Moreover, U.S. physicians must obtain consent from patients before per-forming any procedure or risk charges of as-sault and battery [23]. Furthermore, for the patient’s consent to be valid under law, the pa-tient must have sufficient information on which to base the decision [26].

TABLE 3: Institutional Guidelines for Informed Consent Institutional Guidelines? Number % Yes 60 66.7 No 30 33.3 Total 90a

aOne of the 91 responding medical centers did not

answer this item.

100.0

TABLE 4: Personnel Who Inform Patients About CT

Position of Informer Number % Ordering physician 19 20.9 Radiologist 14 15.4 Radiology technologist 38 41.8 Othersa

aThis includes nurses, residents, and clerical staff.

15 16.5

Total no. medical centers reporting

60

Note—Total number of responses, 86, is greater than total number of centers reporting they have guidelines for informing patients, 60, because of multiple responses from some individual centers.

TABLE 5: Oral or Written Information About CT Scans

Method of

Informing Patients Number %

Oral 30 50.0

Written 3 5.0

Both oral and written 25 41.7

No response selected 2 3.3

Total 60a 100.0

aOnly 60 of the 91 centers offer this information to

their patients.

TABLE 6: CT Scan Purpose

Are Patients Informed of Purpose of CT

Before Administered? Number %

Yes 66 72.5

No 19 20.9

Don’t know 5 5.5

No answer selected 1 1.1

Total 91 100.0

Our study shows that 50% of patients are verbally informed about CT scans in academic medical centers, and 5% receive only written information. The remaining 42% of sites use both verbal and written methods of consent. This study finding agrees with previous studies that have examined informed consent for IV in-jection of contrast material before radiographic studies [27]. Although written consent proce-dures are reproducible, create documentation, and standardize the communication of risks, limitations in obtaining written informed con-sent are numerous including patient under-standing, legal department time, and costs [17]. Also, patients may prefer to obtain information person-to-person, enabling discussion with health care providers and offering opportunities for clarification and support [28].

In routine health care delivery, providers may be comfortable eliciting an “informal” informed consent from patients. However, this informality should not undermine the need for patients to understand a test’s indi-cations and appreciate its benefits, risks, and

limitations [29]. In the case of diagnostic CT scans, which some would categorize as rou-tine delivery of care, this principle still holds. Based on our study’s findings, we contend that this information is currently disseminated to patients through a combina-tion of written and verbal methods. The find-ings also suggest that providing patients with information necessary to make an in-formed decision regarding diagnostic CT scans occurs in two parts: (1) at the time the ordering physician informs the patient about the purpose of the CT scan, and (2) when the radiology technologist discloses the associ-ated risks of CT.

CT Scan Purpose

Our results show that the ordering physician is most likely to inform patients about the need for the diagnostic CT scan; however, this duty is sometimes left to others, most commonly the radiology technologist. This same technologist is also the person most likely to inform patients about possible risks. For interventional radiol-ogy procedures, most authorities agree that the radiologists should obtain informed consent [16, 23]. Although diagnostic studies are not as invasive as interventional procedures, informed consent for such studies is usually left to care-takers other than the radiologist.

TABLE 7: CT Scan Risks

Which Risks Are Explained to Patients

Before CT Administered? Number %

Possible allergic reaction to contrast material 76 83.5

Possible radiation risk from procedure 14 15.4

Actual radiation dose to be administered 1 1.1

Othera 9 9.9

None 3 3.3

Don’t know 5 5.5

Total 108 118.7

Note—The total number of responses, 108, is greater than the total number of centers responding, 91, because some centers reported that multiple risks were explained to patients.

aOther risks include radiation risks to pregnant patients and risk of nephrotoxicity.

TABLE 8: Personnel Informing Patients About CT Risks

Who Explains Risks

to Patients? Number % Ordering physician 1 1.1 Radiologist 18 19.8 Radiology technologist 52 57.1 Other(s)a 16 17.6 No one 2 2.2 Don’t know 2 2.2 Total 91 100.0

aOthers include 8.8% nurses, 2.2% either radiology

resident or resident/fellow, and 1.1% nurse or resident or written information was used to explain risks.

TABLE 9: CT Scan Alternatives

Are Patients Informed

of Alternatives to CT? Number % Yes 8 8.8 No 65 71.4 Don’t know 15 16.5 No answer selected 3 3.3 Total 91 100.0

Most of the information communicated to patients after the disclosure of the purpose of the examination by the ordering physician oc-curs between the radiology technologist and patient before, during, and after the CT scan. Although the radiology technologist has more direct interactions with the patient regarding the CT scan, liability associated with obtaining informed consent may still involve the radiol-ogist. Thus, if radiology technologists continue to play a large role in the consent process it is important that the radiology community en-sure that technologists are educated and trained to provide necessary information to pa-tients concerning the risks, benefits, and alter-natives to CT scans.

CT Scan Risks

Currently, radiation exposure and associ-ated risks from diagnostic CT scans are ex-plained to patients in approximately one in eight academic medical centers in comparison with risk associated with contrast administra-tion, which is explained to patients in five of six such centers. Given that guidelines are cur-rently in place at most academic medical cen-ters to disclose the rare morbidity and mortal-ity attributed to acute allergic reactions, we believe that the morbidity and mortality attrib-utable to radiation exposure should also be ex-plained. Low-dose radiation is an important and necessary medical tool, but it is also con-sidered a carcinogen [30] and should be dis-closed for both ethical and legal reasons.

Contrary to arguments that informing pa-tients about possible risks would cause them undo anxiety, past studies have shown that in most cases disclosure of possible IV contrast reactions did not alter anxiety [31]. Further-more, 90% of patients given a description of risks associated with radiographic contrast material just before undergoing a CT exami-nation said they would rather receive this in-formation than not receive it [17]. Written consent for IV contrast also did not lessen the number of studies performed and offered more specific information to the patient re-garding possible complications [32].

From a medical–legal standpoint, the mal-practice risks arising from allegations of radia-tion injury caused by CT are yet unknown and, thus, unlimited [33]. Thus, it would be prudent for the radiology community to disclose possi-ble radiation risks. In the past, a large part of the limitations in the use of clinical radiology consent forms have been the patient’s inability to understand them. Consent forms for radio-logic procedures have been shown to require a

college education to understand [34], and basic information directed at an eighth grade level of education is recommended [35]. One sug-gested and simple way of communicating the radiation risk to patients is to express radiation dose as multiples of chest radiographs, a method that is widely understood and endorsed by the European Commission’s guidelines on imaging [36].

CT Scan Alternatives

Fewer than 10% of academic medical cen-ters returning surveys stated that they cur-rently inform patients of alternatives to diag-nostic CT scans. Without disclosure of alternative diagnostics, which include not un-dergoing a CT examination at all, the medical community is currently not obtaining com-plete and thorough informed consents from patients before administration of CT. Critics have argued that the time, legal resources, and finances to outline all major benefits, risks, and alternatives to patients would be too costly [37]. Yet, given the large proportion of academic medical centers that report already having guidelines in place regarding many as-pects of informed consent for diagnostic CT scans, we believe that complete disclosure of the benefits, all major risks (including risk from ionizing radiation), and alternatives is currently possible without much added effort, time, or infrastructure.

Study Limitations

Although chairpersons of each medical center’s radiology department were targeted for ease of participant identification and uni-formity of data collected, we acknowledge that the chairpersons may not be as involved in patient care as other physicians in their de-partment. Data from this study are descriptive in nature, and no statistical analyses of signif-icance could be performed. Also, some items allowed respondents to select more than one answer choice, yielding a total greater than 100% response for select survey questions. Finally, although much of the debate concern-ing unnecessary radiation exposure to pa-tients is occurring in the outpatient commu-nity setting, our data are specific to U.S. academic medical centers.

Recommendations

We recommend that the U.S. governing ra-diologic bodies follow the lead of the Euro-pean Union and move to develop national pol-icy guidelines regarding screening and diagnostic CT-scan informed consent

prac-tices, and proper disclosure of radiation dose and possible cancer risks to all patients in-volved. Although most academic medical centers currently have guidelines for inform-ing patients regardinform-ing CT scans, its purpose, and some risks, they are not obtaining full in-formed consent because of the failure of dis-closing both the radiation risks and diagnostic alternatives. Such practices disregard patient autonomy and violate common principles of medical ethics.

In particular, physicians and technologists should be educated about the magnitude of di-agnostic CT radiation dose and possible long-term consequences. The disparity in knowl-edge regarding radiation dose from CT scans between radiologists and nonradiologists suggests that current information is not being disseminated from the radiology community to either requesting physicians or patients [38]. Whether provided verbally, in written form, or both, correct and understandable in-formation concerning possible radiation risks among physicians and patients will help the medical community avoid a substantial public health risk and possible malpractice lawsuits. Acknowledgment

We thank the members of the Society of Chairmen in Academic Radiology Depart-ments (SCARD) for their willingness to aid in the dissemination of the study survey.

References

1. Berland LL, Berland NW. Whole-body computed tomography screening. Semin Roentgenol 2003; 38:65–76

2. Illes J, Fan E, Koenig BA, Raffin TA, Kann D, Atlas SW. Self-referred whole-body CT imaging: current implications for health care consumers. Radiology 2003; 228:346–351

3. Food and Drug Administration. Full-body CT scans: what you need to know. DHHS Publication FDA (03)-0001. Available at: www.fda.gov/cdrh/ct/ctscansbro.html. Ac-cessed April 2005

4. Golding SJ, Shrimpton PC. Radiation dose in CT: are we meeting the challenge? Br J Radiol 2002; 75:1–4

5. Haaga JR. Radiation dose management: weighing risk versus benefit. AJR 2001; 177:289–291 6. Brenner DJ. Radiation risks potentially associated

with low-dose CT screening of adult smokers for lung cancer. Radiology 2004; 231:440–445 7. Brenner DJ, Sawant SG, Hande MP, et al. Routine

screening mammography: how important is the ra-diation-risk side of the benefit–risk equation? Int J

Radiat 2002; 78:1065–1067

8. Shrimpton PC, Wall BF. CT: an increasingly impor-tant slice of the medical exposure of patients. Br J Radiol 1993; 66:1067–1068

9. Pierce DA, Preston DL. Radiation-related cancer risks at low doses among atomic bomb survivors. Radiat Res 2000; 154:178–186

10. Preston DL, Shimizu Y, Pierce DA, Suyama A, Mabuchi K. Studies of mortality of atomic bomb survivors: Report 13—solid cancer and noncancer disease mortality, 1950–1997. Radiat Res 2003; 160:381–407

11. Brenner DJ, Ellison CD. Estimated radiation risks potentially associated with full-body CT screening. Radiology 2004; 232:735–738

12. Brenner DJ. Doll R, Goodhead DT, et al. Cancer risk attributable to low doses of ionizing radiation: assessing what we really know. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2003; 100:13761–13766

13. Brenner D, Ellison C, Hall E, Berdon W. Estimated risks of radiation-induced fatal cancer from pediat-ric CT. AJR 2001; 176:289–296

14. National Institute of Environmental Health Sci-ences. List of cancer causing agents grows. (press release) Available at www.niehs.nih.gov/oc/ news/canceragents.htm. Accessed February 5, 2005

15. O’Dwyer HM, Lyon SM, Fotheringham T, Lee MJ. Informed consent for interventional radiology pro-cedures: a survey detailing current European practice. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2003; 26:428–433

16. Obergfell AM. Law & ethics in diagnostic imaging and therapeutic radiology. Philadelphia, PA: Saun-ders, 1995:85–92

17. Spring DB, Winfield AC, Friedland GW, Shuman WP, Preger L. Written informed consent for IV con-trast-enhanced radiography: patient attitudes and common limitations. AJR 1988; 151:1243–1245 18. Neptune SM, Hopper KD, Matthews YL. Risks

as-sociated with the use of IV contrast material: anal-ysis of patient’s awareness. AJR 1994; 162:451–454 19. Neptune SM, Hopper KD, Houts PS, Hartzel JS, Have TR, Loges RJ. Take-home informed consent for intravenous contrast media. Invest Radiol 1996; 31:109–113

20. Earnest F, Swensen SJ, Zink FE. Respecting patient autonomy: screening at CT and informed consent. Radiology 2003; 226:633–634

21. Hall EJ. Lessons we have learned from our children: cancer risks from diagnostic radiology. Pediatr Ra-diol 2002; 32:700–706

22. Cascade PN. Resolved: that informed consent be obtained before screening CT. J Am Coll Radiol 2004; 1:82–84

23. Berlin L. Malpractice issues in radiology: informed consent. AJR 1997; 169:15–18

24. European Commission. Radiation protection 116:

guidelines on education and training in radiation pro-tection for medical exposures. 2003. Available at: europa.eu.int/comm/energy/nuclear/radioprotection/ index_en.htm. Accessed July 5, 2004

25. European Commission. Council Directive 97/43/EURATOM of 30 June 1997 on health pro-tection of individuals against the dangers of ionizing radiation in relation to medical exposure. Official J Eur Commun 1997; 40:L180

26. Bush WH. Should I get informed consent for every procedure and every contrast agent injection? AJR 1994; 163:1522–1525

27. Lambe HA, Hopper KD, Matthews YL. Use of in-formed consent for ionic and nonionic contrast me-dia. Radiology 1992; 184:145–148

28. Chesson RA, McKenzie GA, Mathers SA. What do patients know about ultrasound, CT and MRI? Clin Radiol 2002; 57:477–482

29. Braddock CH, Edwards K, Hasenburg NM, Laidley TL, Levinson W. Informed decision making in out-patient practice: time to get back to basics. JAMA 1999; 282:2313–2320

30. Ron E. Ionizing radiation and cancer risk: evi-dence from epidemiology. Pediatr Radiol 2002; 32:232–237

31. Spring DB, Winfield AC, Friedland GW, Shuman WP, Preger L. Written informed consent for IV con-trast-enhanced radiography: patients’ attitudes and common limitations. AJR 1988; 151:1243–1245 32. Spring DB, Akin JR, Margulis AR. Informed

con-sent for intravenous contrast-enhanced radiogra-phy: a national survey of practice and opinion. Ra-diology 1984; 152:609–613

33. Berlin L. Potential legal ramifications of whole-body CT screening: tacking a peek into Pandora’s box. AJR 2003; 229:289–291

34. Hopper KD, TenHave TR, Hartzel J. Informed con-sent forms for clinical and research imaging proce-dures: how much do patients understand? AJR 1995; 164:493–496

35. Hopper KD, Lambe HA, Shirk SJ. Readability of informed consent forms for use with iodinated con-trast media. Radiology 1993; 187:279–283 36. Picano E. Informed consent and communication of

risk from radiological and nuclear medicine exam-inations: how to escape from a communication in-ferno. BMJ 2004; 329:849–851

37. Nickoloff E. Current adult and pediatric CT doses. Pediatr Radiol 2002; 32:250–260

38. Lee CI, Haims AH, Monico EP, Brink JA, Forman HP. Diagnostic CT scans: assessment of patient, physician, and radiologist awareness of radiation dose and possible risks. Radiology 2004; 231:393–398