ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Psychological Well-being and Relationship Outcomes

in a Randomized Study of Family-Led Education

Susan A. Pickett-Schenk, PhD; Judith A. Cook, PhD; Pamela Steigman, MA; Richard Lippincott, MD; Cynthia Bennett, LPC; Dennis D. Grey, BA

Context:Family members of adults with mental illness often experience emotional distress and strained rela-tionships.

Objective:To test the effectiveness of a family-led edu-cational intervention, the Journey of Hope, in improv-ing participants’ psychological well-beimprov-ing and relation-ships with their ill relatives.

Design and Setting:A randomized controlled trial us-ing a waitus-ing list design was conducted in the commu-nity in 3 southeastern Louisiana cities.

Participants:A total of 462 family members of adults with mental illness participated in the study, with 231 randomly assigned to immediate receipt of the Journey of Hope course and 231 assigned to a 9-month course waiting list.

Intervention:The Journey of Hope intervention con-sisted of 8 modules of education on the etiology and treat-ment of treat-mental illness, problem-solving and communi-cation skills training, and family support.

Main Outcome Measures:Participants’

psychologi-cal well-being and relationships with their ill relatives were assessed at study enrollment, 3 months after enrollment (at course termination), and 8 months after enrollment (6 months after course termination). Mixed-effects random regression analysis was used to predict the like-lihood of decreased depressive symptoms, increased vi-tality, and overall mental health, and improved relation-ship ratings.

Results:Intervention group participants reported fewer depressive symptoms, greater emotional role function-ing and vitality, and fewer negative views of their rela-tionships with their ill relatives compared with control group participants. These improved outcomes were main-tained over time and were significant (P⬍.05 for all) even when controlling for participant demographic and rela-tive clinical characteristics.

Conclusion: Results show that family-led educational interventions are effective in improving participants’ psy-chological well-being and views of their relationships with ill relatives.

Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:1043-1050

N

UMEROUS STUDIES1-5HAVEestablished that families are a primary source of care for adults with men-tal illness. Families fre-quently provide this care with little or no information on the etiology and treat-ment of psychiatric disorders, and with vir-tually no training in symptom manage-ment or problem-solving strategies.6,7They often feel isolated from normative sources of social and emotional support and ig-nored by the mental health system.8,9 Fami-lies report a wide range of consequences related to their caregiving efforts, includ-ing negative effects on their psychologi-cal health and on relationships with their ill relatives. Many family members of adults with mental illness report high levels of

depression and anxiety, poor social func-tioning, and excessive feelings of fear, worry, and guilt,10-14and describe frustrat-ing interactions with their ill rela-tives.15-17A lack of practical knowledge and emotional support may account for these family members’ low levels of emotional well-being and strained relationships with their ill relatives. Studies14,18-20 sug-gest that family members who do not understand that many of their relatives’ behaviors, such as hostility, apathy, and social withdrawal, are psychiatric symptoms falsely attribute these behav-iors to negative aspects of their relatives’ personality; these individuals are more likely to experience psychological dis-tress and express greater criticism of their ill relatives.

Psychosocial interventions that provide education about the etiology of mental illness and standard clini-cal treatments, problem-solving skills training, and fam-ily support have improved famfam-ily members’ ability to cope with their relatives’ illness and reduced their rela-tives’ psychiatric recidivism.5,21,22However, much of this research has focused on family psychoeducational inter-ventions led by mental health professionals as adjuncts to the treatment of the ill relative. Recognized as evidence-based practices for reducing patient

relapse,23-25 psychoeducational programs typically are

clinical-based diagnosis-specific interventions that last 9 months or longer and have the primary goal of improv-ing patient outcomes, with enhanced family outcomes as secondary gains. However, the expense, setting, and length of psychoeducational interventions often limit their dissemination.24,26

Family-led education interventions, such as the Journey of Hope ( JOH) and the National Alliance for the Mentally Ill’s Family-to-Family Education Pro-gram, have increased in number and popularity in the past decade. Delivered by trained volunteer family members, these community-based programs are inde-pendent of patients’ treatment, last 12 weeks or less, and are designed to increase family coping competen-cies via education on the etiology of and clinical treat-ments for mental illness, problem-solving skills training, and emotional support. Family-led interven-tions are widely available, primarily through advocacy organizations.

Despite the growth of these programs, little empiri-cal research has examined the effectiveness of these in-terventions in improving family members’ outcomes. So-cial learning and support theories suggest that interactions with instructors and classmates who are peers (ie, other family members) and who share similar experiences en-hance family-led education program participants’ well-being and strengthen their ability to manage

illness-related problems.27-30Indeed, studies have found that

families who participated in family-led education

inter-ventions reported improved feelings of morale4and

em-powerment.31,32However, participants’ improved

out-comes cannot be attributed to the interventions alone, given these studies’ use of naturalist and quasi-experimental designs.

This randomized clinical trial overcomes this knowl-edge gap by examining whether participation in JOH, a family-led education intervention, improves family mem-bers’ mental health and the quality of their relationships with ill relatives. We tested 3 hypotheses: (1) compared with control participants, intervention group partici-pants would report fewer depressive symptoms, en-hanced emotional well-being, and improved relation-ships with their ill relatives; (2) the differences between intervention and control participants would be main-tained over time; and (3) these differences would per-sist despite the effects of family members’ demographic characteristics and the clinical features of their relatives’ illnesses.

METHODS

PARTICIPANTS

We conducted the study in 3 urban areas in Louisiana: Baton Rouge, Lafayette, and New Orleans. In each city (hereafter re-ferred to as study site), relatives of adults with mental illness were recruited through newspaper advertisements; flyers dis-tributed at mental health clinics, hospitals, libraries, churches, and grocery stores; televised public service announcements; and referrals from psychiatrists and social workers. Interested in-dividuals used a toll-free number to contact the study office in Baton Rouge and were screened via telephone for eligibility cri-teria. Study inclusion criteria were as follows: being the rela-tive of an adult diagnosed as having 1 of the 5 mental disor-ders covered in the JOH curriculum (schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, bipolar disorder, depression, and ob-sessive-compulsive disorder), being 18 years or older, having the desire to participate in the JOH intervention and the re-search, and having the ability to provide informed consent. In-dividuals uncertain of their relatives’ diagnosis were screened again by 1 of us (R.L.), a board-certified psychiatrist who de-termined whether the relatives’ reported symptoms met the DSM-IV33criteria for one of these disorders. Research staff met with eligible participants to discuss study procedures and obtain in-formed consent. The study was approved by the institutional review boards of the University of Illinois at Chicago and the Louisiana Department of Health and Hospitals.

We recruited, enrolled, and randomized participants in 6 waves at each of the 3 sites, from December 1, 2000, through August 31, 2003. As shown in theFigure, 553 individuals ex-pressed interest in participating in the study; 542 of these in-dividuals met the eligibility criteria, and 72 of these declined participation. A total of 470 individuals consented to partici-553 Individuals Assessed for Eligibility

462 Randomized and Completed the Time 1 Interview

231 Assigned to Intervention

14 Did Not Receive Intervention 168 Received Full Intervention

(≥6 Sessions) 65 Received Part of Intervention

(≤5 Sessions)

231 Assigned to Control

215 Completed Time 2 Interview

1 Withdrew 13 Unable to Be Located

1 Excluded (Received Nonstudy JOH Course)

1 Deceased (Physical Illness Unrelated to Research)

205 Completed Time 3 Interview

4 Withdrew 4 Unable to Be Located

2 Deceased (Physical Illness Unrelated to Research)

214 Completed Time 2 Interview

6 Unable to Be Located 7 Withdrew

4 Excluded (Received Nonstudy JOH Course)

206 Completed Time 3 Interview

2 Unable to Be Located 5 Withdrew

1 Excluded (Received Nonstudy JOH Course)

8 Withdrew Before Randomization 470 Enrolled

72 Declined to Participate 11 Excluded (8 Did Not Have a Relative

With a Mental Illness and 3 Had Previously Taken a JOH Course)

pate; 8 of these individuals decided to withdraw from the study before randomization. All of the remaining 462 participants were included in this analysis.

RANDOMIZATION

Signed consent forms were ordered chronologically, and a com-puter-generated list of random numbers was used to assign par-ticipants to the intervention and control groups. In keeping with JOH program principles, in which members of the same fam-ily are encouraged to take the course together, individuals from the same family group (ie, married couples and siblings) were assigned to the same study condition. A total of 462 partici-pants were randomized: 231 to the intervention group and 231 to the control group.

INTERVENTION

Developed in 1997, the intervention is an 8-week, manual-ized, education course for relatives of adults with mental ill-ness. Journey of Hope is delivered by instructors who are fam-ily members of adults with mental illness. All instructors complete an extensive, mandatory, 2-day training in which they learn standard course delivery methods and how to effectively work with participants.

The goal of the JOH intervention is to provide basic edu-cation and skills training to families of persons with mental ill-ness, and to give them the practical and emotional support they need to sustain them in their role as primary caregivers. Inter-vention objectives for participants include increased knowl-edge of the etiology and treatment of mental illness, improved problem-solving and communication skills, enhanced well-being, improved relationships with ill relatives, and increased collaborations with treatment professionals. The curriculum cov-ers the biological causes of and clinical treatments for the 5 dis-orders previously listed. Communication and problem-solving skills training are taught and practiced. Participants learn about the mental health service system, how to work with treat-ment providers, the impact of substance use on psychiatric symp-toms and treatment, crisis management, problem-solving tech-niques, and emotional coping strategies. Empathy for ill relatives and methods to facilitate their recovery are emphasized through-out the course. The curriculum also focuses on the emotions family members commonly experience, and helps partici-pants recognize and accept that these emotions are normal re-actions to coping with a relative’s mental illness.

The JOH intervention consists of 8 modules that are deliv-ered in weekly 2-hour sessions over a 2-month period (Table 1).

The curriculum is imparted via scripted lectures, group exer-cises, handouts, and videotapes, and is structured to foster group discussion. Classes are taught in publicly accessible commu-nity settings, free of charge, with the typical class size ranging from 10 to 15 participants. At each of the study sites, JOH is provided 1 to 3 times per year by local National Alliance for the Mentally Ill Louisiana affiliates. Journey of Hope is avail-able to anyone with a relationship to an individual with men-tal illness, including parents, siblings, spouses, adult children, other relatives, and friends. Families are encouraged to attend the course together. However, ill relatives are not permitted to participate in the program so that family members feel free to discuss issues related to their relative.

CONTROL GROUP

Control group participants were assigned to a 9-month JOH course waiting list, and were guaranteed receipt of the course after completing their study participation. To assess the integ-rity of this no-treatment condition, we measured receipt of any family education or support services (eg, support groups and advocacy programs) at each assessment point. Most control group participants did not receive such education or support, as described later.

STUDY PROCEDURES

We administered in-person structured interviews to partici-pants at 3 time points: 1 month before the start of the JOH course for the intervention group (time 1, study baseline for control group participants), at JOH course termination (time 2, 3 months after baseline for the control group), and 6 months after course termination (time 3, 8 months after base-line for the control group). Participants’ demographic charac-teristics and ill relatives’ clinical characcharac-teristics (eg, primary diagnosis and age at first hospitalization) were collected at time 1, and additional information on changes in relatives’ psy-chiatric illness (eg, recent inpatient admissions) was collected at times 2 and 3.

[image:3.612.71.534.71.200.2]Participants received $25 for each interview. All interview schedules were checked, precoded, and entered into a com-mercially available database system (SPSS; SPSS Inc, Chicago, Ill) by Chicago-based research staff. To ensure reliability of data collection throughout the study, interviewers received group training on assessment and coding procedures, and partici-pated in monthly conference calls and quarterly project meet-ings. Routine checks on data quality were conducted through-out the study; these included programmed logic checks at data Table 1. JOH Intervention Modules

Module Content Description

1 Course overview, stages of illness emotional response, and biological causes of mental illness

2 Psychosis, mania, and obsessive-compulsive disorder: symptoms, treatment, coping skills, and recognizing relapse 3 Depression: symptoms, treatment, coping skills, and recognizing relapse; suicide myths and warning signs 4 Bipolar disorder: symptoms, treatment, coping skills, and recognizing relapse; participants discuss personal

reactions to relatives’ illness and emotional stage

5 Schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder: symptoms, treatment, coping skills, and recognizing relapse; dual diagnosis: effect of substance use on symptoms, treatment, coping skills, and recognizing relapse 6 Federal, state, and local service systems, collaborating with treatment providers, and communication skills

7 Problem-solving skills

8 Stages of illness recovery for patients and course summary and celebration

Weekly (all modules) Discussion of stages of emotional response, empathy for ill relatives, and facilitating ill relatives’ recovery

entry and review of frequency distributions of all variables af-terward to identify outlier or out-of-range values.

OUTCOME MEASURES

We examined 7 outcomes using standardized measures with stable psychometric properties. Reliability analyses were con-ducted for each measure at each interview time point. We used the 20-item Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale34and the 8-item depression subscale of the Brief Symp-tom Inventory35to assess participants’ depressive symptoms. Coefficient␣for the Center for Epidemiological Studies De-pression Scale ranged from .76 to .89; and for the Brief Symp-tom Inventory depression subscale, from .82 to .87. The 4 medi-cal and social functioning subsmedi-cales of the Medimedi-cal Outcomes Study 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey36measured partici-pants’ overall mental health (general mental health [5 items]; coefficient␣range, .82-.84), social relationships (social func-tioning [2 items]; coefficient␣range, .73-.84), energy and ac-tivity (vitality [4 items]; coefficient␣, .85 and .86, respec-tively), and role limitations due to emotional problems (role functioning–emotional [3 items]; coefficient␣, .80 and .82, re-spectively). We used the 7-item negative relationship subscale from the You and Your Family Scale37,38to assess participants’ ratings of their relationships with their ill relatives (coefficient ␣, .81 and .82).

DATA ANALYSES

We analyzed the outcome data in 3 stages. We began by visu-ally examining the longitudinal relationships between study con-dition and each of the 7 outcome measures. Next, we tested the cumulative effect of study condition on each outcome us-ing unadjusted bivariate analyses. We then conducted multi-variate, longitudinal, fixed-effects, random regression analy-ses to test for differences between intervention and control conditions over time. A 2-level random intercepts model was fit to the data, controlling for participant demographic and ill

relative psychiatric illness characteristics as fixed effects. Ran-dom regression models were chosen to address longitudinal data concerns, such as state dependency or serial correlation among repeated observations within individual participants, missing observations because not all participants completed all inter-views, individual heterogeneity or varying propensities to-ward the outcomes of interest because of participants’ predis-positions and other unobserved influences, and the inclusion of fixed covariates (educational level, marital status, diagno-sis, illness length, and lifetime inpatient admissions).39 Covar-iates were chosen based on prior studies11,13,38,40that suggest that these family and ill relative demographic and clinical char-acteristics may affect psychological well-being and familial re-lationship assessments.

RESULTS

PARTICIPANT CHARACTERISTICS

Participant demographic characteristics and relatives’

clini-cal characteristics are presented inTable 2. The

suc-cess of the study’s randomization procedures was con-firmed by the absence of statistically significant differences at time 1 between intervention and control group par-ticipants regarding sex, marital status, educational level, and relationship to ill relative. No significant differ-ences were found regarding the ill relative’s age, sex, ill-ness length, number of hospitalizations, and diagnosis of schizophrenia.

INTERVENTION IMPLEMENTATION

Fidelity

[image:4.612.74.546.70.256.2]The intervention was delivered at each site by a team of 2 trained instructors. With the exception of the Baton Table 2. Participant and Ill Relative Characteristics by Study Condition*

Characteristic Intervention Group†‡ Control Group†§ Statistic PValue

Participants

Age, y㛳 51.8 (13.2) 50.7 (12.5) t460= 0.96 .33

Female sex 182 (78.8) 190 (82.3) 2

1= 0.88 .35

Married 149 (64.5) 145 (62.8) 2

1= 0.15 .69

College graduate 86 (37.2) 91 (39.4) 2

1= 0.23 .63

Relationship to ill relative¶

Parent 129 (55.8) 126 (54.5) 2

4= 2.44 .66

Sibling 30 (13.0) 27 (11.7)

Adult child 30 (13.0) 29 (12.6)

Spouse 22 (9.5) 32 (13.9)

Other 20 (8.7) 17 (7.4)

Ill relative

Age, y㛳 36.16 (16.28) 36.30 (16.69) t365= −0.08 .93

Male sex 92 (51.7) 105 (55.0) 2

1= 0.40 .53

Ill forⱖ10 y 90 (50.6) 95 (49.7) 2

1= 1.37 .50

No. of prior hospitalizations㛳 3.82 (7.90) 2.97 (4.52) t358= 1.27 .20

Diagnosed as having schizophrenia 33 (18.5) 33 (17.3) 2

1= 0.10 .75

*Numbers and degrees of freedom vary because of missing data.

†Data are given as number (percentage) of each group unless otherwise indicated. ‡N = 231 for the participants and N = 178 for the ill relatives.

§N = 231 for the participants and N = 191 for the ill relatives. 㛳Data are given as mean (SD).

Rouge site, the same pair of instructors delivered all waves of the intervention. In Baton Rouge, one instructor taught only the first wave of the intervention and was replaced by another trained instructor who taught the remaining 5 waves. A second instructor taught half of the waves (n=3) and was replaced by another trained instructor who taught the final 3 waves of the intervention.

Before intervention implementation, all instructors attended a 2-day training session that included a review of standard curriculum content and training on pre-scribed instruction procedures for the intervention. A log assessing fidelity to curriculum content and adher-ence to prescribed instruction procedures was developed for each of the 8 modules. Following each class, the study coordinator (C.B.) telephoned instructors and completed the log for that module to determine fidelity to the content prescribed for that module (eg, brain biol-ogy, behavior management strategies) and prescribed instructional modalities (eg, videotape, role play exer-cise). Each log component was scored as 1 if the pre-scribed element occurred, and 0 otherwise. Fidelity scores were computed as the proportion of prescribed elements present for that module. Across all modules taught in all waves, total course fidelity ranged from 89.9% to 100.0%, with a mean of 96.6%. There were no significant differences in course fidelity across waves (2

75= 84.00,P=.22), by site (230= 30.00,P=.47), or by instructor (2

49= 56.00,P=.23). Overall, results indicate excellent intervention fidelity.

Intervention Completion Rates

Attendance logs for each participant were maintained by instructors with the help of research staff. Attendance at each class was coded as 1 for presence and 0 for ab-sence, and total attendance was computed by summing attendance scores for each class. On average, partici-pants attended 6 of 8 classes (mean, 5.98 classes; SD, 2.34 classes). There were no significant differences in atten-dance by wave (F5,225= 1.28, P=.27), site (F2,228= 0.58, P=.56), or instructor (F7,85=1.15,P=.34). Reasons for non-attendance were assessed at time 2 and included work-schedule conflicts, physical illness, transportation prob-lems, and conflicts with ill relatives.

Receipt of Nonintervention Education and Support Services

There were no significant differences in intervention and control group participants’ use of nonintervention fam-ily education and support services across the study pe-riod. At time 1, 34 (14.7%) of the intervention group par-ticipants and 34 (14.7%) of the control group parpar-ticipants reported that they were receiving some education and sup-port services (2

1= 0.00,P⬎.99). At time 2, 32 (14.9%)

of the intervention group participants and 25 (11.7%) of the control group participants reported receipt of such services (2

1=0.95,P=.33); and at time 3, 12 (5.8%) of the intervention group participants and 19 (9.2%) of the con-trol group participants reported use of family education or support services (2

1= 1.67,P=.20).

FOLLOW-UP RATES AND ATTRITION

As shown in the Figure, 429 subjects (92.9%) com-pleted time 2 interviews and 411 (89.0%) comcom-pleted time 3 interviews, for a combined attrition rate of 11.0%. There were no statistically significant differences in follow-up rates between intervention and control conditions. At time 2, 215 (93.1%) of the intervention group participants and 214 (92.6%) of the control group participants com-pleted interviews (2

1=0.03;P=.86); at time 3, 205 (88.7%) of the intervention group participants and 206 (89.2%) of the control group participants completed interviews (2

1= 0.02,P=.88). There were no statistically significant differences between participants who completed inter-views and those who did not complete interinter-views re-garding study condition or model covariates, with one exception: participants whose ill relatives had a primary diagnosis of schizophrenia were less likely to complete time 3 interviews (2

1= 4.23,P=.04).

EMOTIONAL WELL-BEING AND RELATIONSHIPS WITH ILL RELATIVES

We graphed and visually inspected the longitudinal re-lationship between study condition and outcome for each of the 7 dependent variables. Bivariate analyses of emo-tional well-being indicate that intervention group sub-jects had significantly fewer depressive symptoms as mea-sured by the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale at time 2 (mean, 16.37 vs 17.91;

t427= −2.02,P=.04) and as measured by the Brief

Symp-tom Inventory at time 3 (mean, 7.95 vs 8.71;t409= −2.25,

P=.02), and greater time 2 emotional role functioning

(mean, 79.22 vs 70.56;t427= 2.48,P=.01). Intervention group participants reported less negative views of their relationships with their ill relatives at time 2 (mean, 13.63 vs 14.28;t425= −2.09,P=.04) and at time 3 (mean, 13.44 vs 14.12;t405= −2.02,P=.04).

Next, we conducted multivariate random regression model analyses with each of the outcomes as the depen-dent measure and study condition as the independepen-dent vari-able, controlling for participant and ill relative

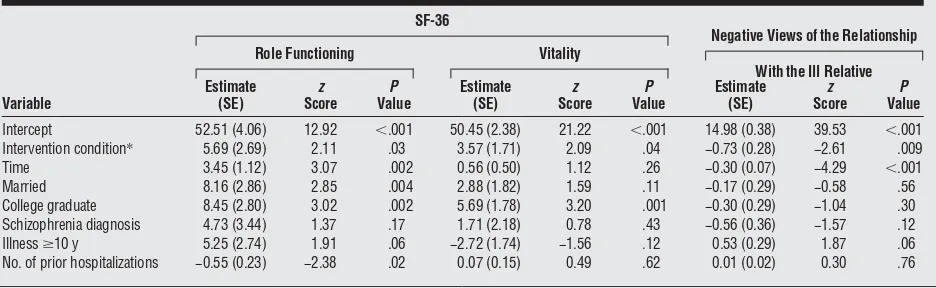

con-founds as described earlier. The results (Table 3and

improved relationships with ill relatives throughout the study period. Finally, none of the participants’ demo-graphic characteristics or the relatives’ clinical charac-teristics were consistently significant across outcomes.

COMMENT

Despite their demonstrated effectiveness in improving family members’ ability to cope with their relatives’ men-tal illness, professional-led psychoeducation programs may be less accessible to families compared with family-led interventions, such as JOH and the Family-to-Family Edu-cation Program.24,26,32Given the potentially greater dis-semination, availability, and, therefore, use of family-led education interventions, establishing their effectiveness in regard to family outcomes is critical. Our study find-ings contribute to this empirical effort. Random regres-sion model results indicate that, compared with those as-signed to the control condition, family members who received the 8-week JOH intervention reported fewer de-pressive symptoms, enhanced emotional role function-ing, greater vitality, and improved views of their

rela-tionships with their ill relatives. Intervention group participants’ superior outcomes were significant even when controlling for the effect of participant demo-graphic characteristics and ill relative clinical character-istics. Furthermore, these differences were maintained over time.

We surmise that JOH intervention participation im-proves family members’ emotional well-being in ways pos-ited by social support and learning theories (ie, expo-sure to and interactions with similar others strengthens

coping ability).27-30First, a common finding in the

[image:6.612.72.543.74.222.2]re-search literature4,31,41on family education programs is that exposure to others who also have relatives with mental illness and who share similar caregiving experiences de-creases participants’ feelings of guilt, shame, and isola-tion. Thus, JOH participants’ psychological well-being may have improved as a result of interactions with other fam-ily members on whom they might rely for advice, friend-ship, and affirmation of their caregiving efforts. Second, as peers who personally understand the problems asso-ciated with psychiatric disorders, JOH instructors serve as credible role models for participants.29Interactions with Table 3. Effects of Study Condition (Intervention vs Control) on Participant CES-D, BSI Depression Subscale,

and SF-36 General Mental Health and Social Functioning Outcomes

Variable

CES-D BSI Depression Subscale

SF-36

General Mental Health Social Functioning

Estimate (SE)

z Score

P Value

Estimate (SE)

z Score

P Value

Estimate (SE)

z Score

P Value

Estimate (SE)

z Score

P Value

Intercept 20.48 (1.14) 17.97 ⬍.001 57.35 (1.03) 55.67 ⬍.001 61.29 (2.16) 28.36 ⬍.001 64.26 (2.81) 22.88 ⬍.001 Intervention condition* −1.64 (0.82) −1.99 .04 −1.51 (0.22) −2.06 .04 2.73 (1.55) 1.76 .08 3.47 (1.94) 1.79 .07 Time −1.37 (0.25) −5.56 ⬍.001 −0.68 (0.22) −3.05 .002 1.02 (0.47) 2.15 .03 3.39 (0.69) 4.91 ⬍.001 Married −2.64 (0.87) −3.03 .002 −2.51 (0.78) −3.21 .001 3.78 (1.64) 2.31 .02 4.93 (2.06) 2.39 .02 College graduate −3.44 (0.85) −4.03 ⬍.001 −2.26 (0.76) −2.97 .002 5.06 (1.61) 3.15 .001 5.79 (2.02) 2.87 .004 Schizophrenia diagnosis −1.49 (1.04) −1.43 .15 −1.63 (0.94) −1.75 .08 3.61 (1.97) 1.83 .07 4.78 (2.48) 1.93 .05 Illnessⱖ10 y −1.14 (0.84) −1.37 .17 −0.33 (0.75) −0.45 .65 2.56 (1.58) 1.62 .10 −0.42 (1.98) −0.21 .83 No. of prior hospitalizations 0.13 (0.07) 1.79 .07 −0.02 (0.06) −0.39 .70 0.05 (0.13) 0.41 .68 −0.11 (0.17) −0.64 .52

Abbreviations: BSI, Brief Symptom Inventory; CES-D, Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale; SF-36, 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey. *For this variable, 1 indicates the intervention group; and 0, the control group.

Table 4. Effects of Study Condition (Intervention vs Control) on Participant SF-36 Role Functioning and Vitality Outcomes and on the Relationship With the Ill Relative

Variable

SF-36

Negative Views of the Relationship

With the Ill Relative Role Functioning Vitality

Estimate (SE)

z Score

P Value

Estimate (SE)

z Score

P Value

Estimate (SE)

z Score

P Value

Intercept 52.51 (4.06) 12.92 ⬍.001 50.45 (2.38) 21.22 ⬍.001 14.98 (0.38) 39.53 ⬍.001

Intervention condition* 5.69 (2.69) 2.11 .03 3.57 (1.71) 2.09 .04 −0.73 (0.28) −2.61 .009

Time 3.45 (1.12) 3.07 .002 0.56 (0.50) 1.12 .26 −0.30 (0.07) −4.29 ⬍.001

Married 8.16 (2.86) 2.85 .004 2.88 (1.82) 1.59 .11 −0.17 (0.29) −0.58 .56

College graduate 8.45 (2.80) 3.02 .002 5.69 (1.78) 3.20 .001 −0.30 (0.29) −1.04 .30

Schizophrenia diagnosis 4.73 (3.44) 1.37 .17 1.71 (2.18) 0.78 .43 −0.56 (0.36) −1.57 .12

Illnessⱖ10 y 5.25 (2.74) 1.91 .06 −2.72 (1.74) −1.56 .12 0.53 (0.29) 1.87 .06

No. of prior hospitalizations −0.55 (0.23) −2.38 .02 0.07 (0.15) 0.49 .62 0.01 (0.02) 0.30 .76

Abbreviation: See Table 3.

[image:6.612.74.542.294.438.2]instructors who are perceived to be successfully meet-ing the challenges of their own relatives’ illness may strengthen participants’ sense of well-being and confi-dence in their ability to do the same. Third, enhanced well-being also may be because of group discussions of the emotional cycles families typically experience in re-action to their relatives’ mental illness. During these dis-cussions, JOH participants are encouraged to express feel-ings of anger and sadness, identify and implement strategies for self-care, and develop plans to move for-ward with their own lives. Sharing these feelings with oth-ers who face similar problems may decrease feelings of powerlessness and hopelessness and increase feelings of self-efficacy.

Our results confirm prior education intervention stud-ies18,42-44that suggest that teaching families about the bio-logical causes of mental illness may improve their views of their relationships with their ill relatives by helping them understand that symptoms such as social isolation and leth-argy are the by-product of psychiatric disorders, and not willful behaviors. In addition to curriculum on the etiol-ogy of mental illness, other features of the JOH course also may contribute to this finding. One of the innovative com-ponents of this intervention is its emphasis on patient re-covery. “Person first” concepts (ie, that the person is not the illness) are stressed throughout the course. Partici-pants learn to work with, rather than for or against, their ill relatives, and to honor their relatives’ choices about treat-ment and personal life goals. These unique course fea-tures, combined with receipt of didactic information about the etiology of mental illness, may decrease families’ nega-tive relationship assessments.

Although intervention group participants had signifi-cantly greater improvements in outcomes, controls also exhibited improved outcomes throughout the study pe-riod. This reflects a process defined by Solomon and

col-leagues45as continued maturation, during which

fami-lies’ ability to cope with their relatives’ mental illness naturally increases over time. The difference in out-comes between the 2 groups suggests that receipt of edu-cation may accelerate this process for intervention group participants, enabling them to more quickly achieve gains in their emotional well-being and relationships with their ill relatives.

There are several study limitations. Given our use of an inactive control group, it is possible that intervention participants’ improved outcomes may be placebo effects resulting from simply receiving attention from JOH structors and classmates, rather than because of the in-tervention itself. Although use of an attention control group may have been preferable, evidence suggests that

such groups may increase human subjects’ risks.46We

determined that depriving control group participants who enrolled in the study seeking family-led education of any opportunity to receive the JOH intervention following their research participation was unethical. An addi-tional concern was the potential for higher attrition rates among controls because of nonreceipt of a family-led in-tervention. We, therefore, chose a waiting list design guar-anteeing receipt of the intervention to minimize these risks. The intention of our randomized clinical trial was to test the intervention in a population in which it is

tra-ditionally offered and in a way that did not alter pro-gram principles. Thus, the generalizability of our find-ings is limited by the fact that we did not draw subjects from a national probability sample of relatives of adults with mental illness or from clinical populations. In-stead, we tested the intervention in Louisiana sites where the program is offered regularly by the National Alli-ance for the Mentally Ill Louisiana affiliates, and, in ac-cordance with JOH program principles, used passive re-cruitment strategies to enroll family members who voluntarily sought assistance in dealing with their rela-tives’ mental illness. We believed it unfair to require con-trol participants to wait a year or more to receive the JOH course; thus, our use of a 6-month postintervention fol-low-up does not allow us to determine whether out-come gains were maintained long-term (ie, 12 or 24 months’ postintervention). Finally, we did not test changes in family members’ relationships with their ill relatives, only their self-reported ratings of these relationships. We, therefore, cannot determine whether intervention par-ticipation results in actual improvements in these rela-tionships, such as fewer arguments or more quality time spent with ill relatives.

In sum, the results of our randomized clinical trial con-tribute to the emerging research establishing family-led educational interventions as an evidence-based prac-tice.32,47Specifically, our findings suggest that participa-tion in family-led educaparticipa-tion programs increases family members’ coping ability by decreasing depressive symp-toms, enhancing emotional well-being and vitality, and improving their views of their relationships with their ill relatives. Changes in these outcomes suggest that fam-ily-led interventions may have important clinical impli-cations. Many family members experience poor psycho-logical health and discordant relationships related to their caregiving efforts10-17; interventions such as JOH and the Family-to-Family Education Program may be effective, accessible, and affordable tools in reducing distress among this population. Given the growth and availability of these programs, additional analyses—and additional random-ized clinical trials of family-led education interventions— are needed to determine the effect of program participa-tion on other outcomes, such as knowledge of the etiology and treatment of psychiatric disorders, and to further es-tablish these interventions’ efficacy in improving family members’ ability to cope with their adult relatives’ men-tal illness.

Submitted for Publication:July 18, 2005; final revision received January 13, 2006; accepted January 19, 2006. Correspondence:Susan A. Pickett-Schenk, PhD, Depart-ment of Psychiatry, University of Illinois at Chicago, 1601 W. Taylor, Chicago, IL 60612 (pickett@psych.uic.edu). Funding/Support:This study was supported by grant R01 MH60721 from the National Institute of Mental Health. Disclaimer:The contents of this article do not reflect the official position of the National Institute of Mental Health and no endorsement should be inferred.

REFERENCES

1. Goldman HH. Mental illness and family burden: a public health perspective.Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1982;33:557-560.

2. Baronet AM. Factors associated with caregiver burden in mental illness: a criti-cal review of the research literature.Clin Psychol Rev. 1999;19:819-841. 3. Lefley HP.Family Caregiving in Mental Illness.Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage

Pub-lications; 1996.

4. Pickett-Schenk SA, Cook JA, Laris A. Journey of Hope program outcomes. Com-munity Ment Health J. 2000;36:413-424.

5. Ohaeri JU. The burden of caregiving in families with a mental illness: a review of 2002.Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2003;16:457-465.

6. Marsh DT, Johnson DL. The family experience of mental illness: implications for intervention.Prof Psychol Res Pr. 1997;28:229-237.

7. Solomon P, Draine J, Mannion E, Meisel M. Increased contact with community mental health resources as a potential benefit of family education.Psychiatr Serv. 1998;49:333-339.

8. Magliano L, Marasco C, Fiorillo A, Malangone C, Guarneri M, Maj M. The impact of professional and social network support on the burden of families of patients with schizophrenia in Italy.Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2002;106:291-298. 9. Solomon P, Marcenko M. Families of adults with mental illness: their

satisfac-tion with inpatient and outpatient treatment.Psychosoc Rehabil J. 1992;16: 121-134.

10. Marsh D.Families and Mental Illness: New Directions in Professional Practice.

Westport, Conn: Praeger Publishers; 1992.

11. Seltzer MM, Greenberg JS, Floyd FJ, Hong J. Accommodative coping and well-being of midlife parents of children with mental health problems or developmen-tal disabilities.Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2004;74:187-195.

12. Seltzer MM, Greenberg JS, Krauss MW. A comparison of coping strategies of aging mothers of adults with mental illness or mental retardation.Psychol Aging. 1995;10:64-75.

13. Martens L, Addington J. The psychological well-being of family members of in-dividuals with schizophrenia.Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2001;36: 128-133.

14. Rauktis ME, Koeske GF, Tereshko O. Negative social interactions, distress, and depression among those caring for a seriously and persistently mentally ill relative.

Am J Community Psychol. 1995;23:279-299.

15. Cook JA, Pickett SA. Feelings of burden and criticalness among parents resid-ing with chronically mentally ill offsprresid-ing.J Appl Soc Sci. 1988;12:79-107. 16. Cook JA, Lefley HP, Pickett SA, Cohler BJ. Age and family burden among

par-ents of offspring with severe mental illness.Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1994;63: 435-447.

17. Greenberg JS, Seltzer MM, Greenley JR. Aging parents of adults with disabili-ties: the gratifications of later life caregiving.Gerontologist. 1993;33:542-550. 18. Harrison CA, Dadds MR, Smith G. Family caregivers’ criticism of patients with

schizophrenia.Psychiatr Serv. 1998;49:918-924.

19. Vaughn CE, Leff JP. The influence of family and social factors on the course of psychiatric illness: a comparison of schizophrenic and depressed neurotic patients.

Br J Psychiatry. 1976;129:125-137.

20. Hooley JM, Campbell C. Control and controllability: beliefs and behaviour in high and low expressed emotion relatives.Psychol Med. 2002;32:1091-1099. 21. Dixon LB, Lehman AF. Family interventions in schizophrenia.Schizophr Bull. 1995;

21:631-643.

22. Barbato A, D’Avanzo B. Family interventions in schizophrenia and related disor-ders: a critical review of clinical trials.Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2000;102:81-97.

23. Dixon L, Adams C, Lucksted A. Update on family psychoeducation for schizophrenia.

Schizophr Bull. 2000;26:5-20.

24. Dixon L, McFarlane WR, Lefley H, Lucksted A, Cohen M, Falloon I, Mueser K, Miklowitz D, Solomon P, Sondheimer D. Evidence-based practices for services to families of people with psychiatric disabilities.Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52: 903-910.

25. New Freedom Commission on Mental Health.Achieving the Promise: Trans-forming Mental Health Care in America: Final Report. Rockville, Md: New Free-dom Commission on Mental Health; 2003. DHHS publication SMA-03-2832. 26. McFarlane WR, McNary S, Dixon L, Hornby H, Cimett E. Predictors of

dissemi-nation of family psychoeducation in community mental health centers in Maine and Illinois.Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52:935-942.

27. Bandura A.Social Learning Theory.Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1977. 28. Sarason I, Levine H, Basham R, Sarason B. Assessing social support: the social

support questionnaire.J Pers Soc Psychol. 1983;44:127-139.

29. Salzer MS, Shear SL. Identifying consumer-provider benefits in evaluations of consumer-delivered services.Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2002;25:281-288. 30. Solomon P. Peer support/peer provided services underlying processes,

ben-efits, and critical ingredients.Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2004;27:392-401. 31. Dixon L, Stewart B, Burland J, Delahanty J, Lucksted A, Hoffman M. Pilot study

of the effectiveness of the family-to-family education program.Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52:965-967.

32. Dixon L, Lucksted A, Stewart B, Burland J, Brown CH, Postrado L, McGuire C, Hoffman M. Outcomes of the peer-taught 12-week family-to-family education program for severe mental illness.Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2004;109:207-215. 33. American Psychiatric Association.Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental

Disorders, Fourth Edition.Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994.

34. Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population.Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1:385-401.

35. Derogatis LR.Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI): Administration, Scoring and Pro-cedures Manual.Minneapolis, Minn: National Computer Systems; 1993. 36. Ware JE, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36),

I: conceptual framework and item selection.Med Care. 1992;30:473-483. 37. Cohler BJ.The You and Your Family Scale.Chicago, Ill: University of Chicago;

1986.

38. Pickett SA, Cook JA, Cohler BJ, Solomon ML. Positive parent/adult child rela-tionships: impact of severe mental illness and caregiving burden.Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1997;67:220-230.

39. Gibbons RD, Hedeker D, Elkin I, Waternaux C, Kraemer HC, Greenhouse JB, Shea MT, Imber SD, Sotksy SM, Watkins JT. Some conceptual and statistical issues in analysis of longitudinal psychiatric data: application to the NIMH Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program dataset.Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1993; 50:739-750.

40. Magliano L, Fiorillo A, De Rosa C, Malangone C, Maj M; National Mental Health Project Working Group. Family burden in long-term diseases: a comparative study in schizophrenia vs physical disorders.Soc Sci Med. 2005;61:313-322. 41. Solomon P. Moving from psychoeducation to family education for families of

adults with serious mental illness.Psychiatr Serv. 1996;47:1364-1370. 42. Halford WK, Hayes R. Psychological rehabilitation of chronic schizophrenic

pa-tients: recent findings on social skills training and family psychoeducation.Clin Psychol Rev. 1991;11:23-44.

43. Glick ID, Spencer JH Jr, Clarkin JF, Haas GL, Lewis AB, Peyser J, DeMane N, Good-Ellis M, Harris E, Lestelle V. A randomized clinical trial of inpatient family intervention, IV: followup results for subjects with schizophrenia.Schizophr Res. 1990;3:187-200.

44. Buchkremer G, Holle R, Schulze Mo¨nking H, Hornung WPS. The impact of thera-peutic relatives’ groups on the course of illness in schizophrenic patients.Eur Psychiatry. 1995;10:17-27.

45. Solomon P, Draine J, Mannion E, Meisel M. Effectiveness of two models of brief family education: retention of gains by family members of adults with serious mental illness.Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1997;67:177-186.

46. Street LL, Luoma JB. Control groups in psychosocial intervention research: ethi-cal and methodologiethi-cal issues.Ethics Behav. 2002;12:1-30.

47. Jewell TC, McFarlane WR, Dixon L, Miklowitz DJ. Evidence-based family ser-vices for adults with severe mental illness. In: Stout C, Hayes RA, eds.The Evidence-Based Practice: Methods, Models, and Tools for Mental Health Professionals.