The Attitudes of Separated Resident Mothers in Australia to Children Spending Time with Fathers

August 2006: Revised March 2007

By Dr Elspeth McInnes

School of Education, Magill Campus University of South Australia GPO Box 2471 Adelaide SA 5001 Elspeth.mcinnes@unisa.edu.au

Abstract

Separated mothers are strongly supportive of children spending time with their fathers as long as their children are safe, but fathers’ interest in and availability for contact are the key determinants of contact practices, according to a survey of 175 separated resident mothers in Australia. Mothers who had been afraid of their ex-partner were much more likely to be concerned that their children were safe with their father, however mothers’ attitudes had no significant impact on the frequency of contact. The distance between households was significantly related to child-father contact frequency. Fathers were twice as likely as mothers to cancel or not take planned contact. Child safety and child health were the main reasons mothers gave for stopping contact on few occasions. The research findings point to the policy limitations of perceiving mothers’ attitudes and practices as determinant of post-separation child-father contact and the need for a greater focus on women’s and children’s safety in family law policy.

Introduction

This article reports on some aspects of survey data collected from a sample of 175 separated resident mothers in Australia in late 2005 and early 2006. The research aimed to identify the attitudes of separated mothers to child-father contact, identify the factors which had informed mothers’ attitudes and explore how mothers’ attitudes impacted on child-father contact frequency. Changes in the Family Law Act which took effect on July 1 2006 provide a greater focus on parental responsibility and new penalties for parents who breach contact orders, but mothers’ attitudes and practices of child-parent contact have had little research attention.

The July 2006 changes in the Family Law Act emphasise shared parental responsibility following on from the last major changes in 1996 under the Family Law Reform Act 1995. The 2006 changes focus on the continuing roles and responsibilities of both parents after separation and children’s ‘right to a meaningful relationship’ with both parents. The 1996 family law changes expressed this as children’s ‘right to contact’ (Dewar and Parker 1999; Rhoades 2000). The ‘right to contact’ provisions of the 1996 changes led to a steep rise in litigation, with applications to enforce contact orders growing by more than 100 % since 1996 (Rhoades 2002). Research into the impact of the Family Law Reform Act 1995 identified that most of the contact enforcement applications were being filed by unrepresented non-resident fathers whose applications where ‘unmeritorious’ and being used as a means of harassing the resident parent (Rhoades, Harrison & Graycar 1999, p.10)

Widespread anecdotal evidence from non-resident fathers of ‘denial of contact’ by resident mothers (Kaye and Tolmie 1998) led to the development of an enforcement and penalty model by the Family Law Council (1998, 1998a). The research evidence from court files does not however support claims of widespread ‘denial of contact’ (Rhoades 2002; Rhoades et al. 1999; 2001). The complexities of

difficult contact cases were indicated in Rhoades’ (2002) study of court files where mothers were alleged to have breached contact orders. She found that issues of domestic violence and child abuse were strong themes in the evidence on factors impeding contact, alongside changed circumstances where the orders had ceased to be suitable or possible to meet. Additional penalties and processes for contravention of orders have now been implemented in the Family Law Amendment (Shared Parental Responsibility) Act 2005.

Most contact arrangements are not resolved in court, but rather by

agreements between parents (Family Court of Australia 2003) and there is evidence that many mothers want more child-father contact to occur. Parkinson and Smyth (2003) drew on data from 1,041 separated parents and identified that 74% of non-resident fathers wanted more time with their children and 41% of non-resident mothers wanted fathers to spend more time with their children. The finding that two in five resident mothers wanted more paternal involvement is not consistent with men’s rights groups’ claims that denial of contact by mothers is the primary reason fathers do not spend more time with their children after separation (Kaye & Tolmie 1998, 1998a).

Data from 1039 separated parents collected in the 2001 HILDA survey showed that ‘standard’ contact patterns of every weekend or second weekend accounted for 42.5%; 35 % had little or no contact, 16.5 % had daytime only contact and 6 % had shared care (Smyth, Qu & Weston 2004).

Smyth, Caruana and Ferro (2004) conducted focus groups with separated parents on patterns of contact. The focus group data when contact parents had ‘little or no contact’ showed divergent interpretations from resident mothers and contact fathers of the reasons for this outcome. Disengaged contact fathers saw themselves as ‘cut out’ of their children’s lives, but resident mothers saw their ex-partners as

‘opting out’. Those fathers who had continuing conflict with their former partner perceived that ‘maternal obstruction’ had led them to disengage from their children, while resident mothers gave ‘paternal disinterest’ more prominence. The HILDA data for the ‘little or no contact’ parents showed that fathers in particular were more likely to be re-partnered and the parents were more likely to be more than 50

kilometres apart. Mothers reported stresses around their perceptions of fathers’ limited parenting skills, lack of respite from sole responsibility and children’s disappointment when fathers did not take expected contact, whilst fathers spoke of the ‘shallowness’ of limited contact (Smyth, Caruana & Ferro 2004 p.23-24.) Those parents in the ‘daytime only’ contact group also featured the polarised interpretations of ‘maternal obstruction’ from fathers, versus perceived ‘paternal disinterest’ and concerns for children’s safety from mothers. Repartnering and distance between households were again common themes surrounding limited child-father contact (Smyth et al. 2004 p.26).

Research by McInnes (2001) into single mothers’ transitions into a single parent household found that contact occurred in single mother families where fathers wanted contact, and did not occur when fathers did not seek or take contact. The data indicated that the mothers’ concerns about their own and their children’s safety did not have a determinant impact on child-father contact outcomes as none of these mothers was able to prevent continuing child-father contact in cases involving abuse of the children.

A study by Kaspiew (2005) of 40 randomly selected contested children’s cases in the Family Court found that a history of violence presented no barrier to child-father contact in court decision-making unless the violence was ‘extremely severe and has a firm evidential basis.’

The most common judicial response to managing parent-child contact where violence was an issue was to order supervised contact, either through family

members or friends or a children’s contact service (Rhoades et al. 2001). A major evaluation of children’s contact services found that 78 % of the client group had concerns with domestic violence and/or child abuse, whilst 70 % of client cases featured complex circumstances (Sheehan, Carson, Fehlberg, Hunter, Tomison, Ip & Dewar 2005). The researchers found that there was a high risk of violence or abuse occurring without access to supervised contact or changeover. In 5 % of cases in the study, contact centres had withdrawn their service due to safety concerns. The researchers identified a subset of cases which were ‘clearly harmful’ to the child and the target parent and where contact was clearly against children’s interests (Sheehan et al. 2005, p. xvi).

The contact enforcement regime came into effect in April 2001 and provided for a three stage process which aimed to ensure that contact orders were workable and that parents understood the requirements of the orders and the importance of keeping them. The most severe penalty stage provided for fines, community service orders and imprisonment. The Family Law Amendment (Shared Parental Responsibility) Act 2005 further requires the court to consider compensating the contact parent for the costs of contact and awarding costs against the residence parent. As well as legislated penalties, narrative constructions of resident mothers who oppose contact in divorce discourse in Australia and elsewhere now refer to the ‘implacably hostile mother’ (Rhoades 2002, p.78) or to ‘maternal obstruction’ (Smyth et al.2004) or mothers as ‘vengeful’ (Kaganas & Sclater 2004) or ‘wilful’ (Wallbank 1998).

Safety for children remained a key issue for mothers opposing contact. Research by Hume (1996, 2003) Humphreys (1999), Brown, Frederico, Hewitt and Sheehan (1998, 2001, 2001a), McInnes (2003, 2004) Rendell, Rathus and Lynch (2000) ,

Kaye, Stubbs and Tolmie (2003), Fehlberg and Kelly (2000), Kelly and Fehlberg (2002) and the Family Law Council (2002) has identified that there are serious gaps at the intersection of family law and state child protection services. Rendell et al. (2000) found that child-father contact was a key conduit for continuing abuse. The effects on children included nightmares, bed-wetting, anxiety, poor school performance, social withdrawal, bullying others and being bullied.

Kaye, Stubbs and Tolmie (2003) found that professionals were divided over whether contact should go ahead when the contact parent had abused the children and most assumed that violence against mothers was ‘clearly separable from any consideration of the wellbeing of the child’ (p. x). This last finding highlights the failure of professionals involved in parent-child contact to recognise children’s experiences of violence against their mothers as violence to children, despite the extensive research literature documenting the adverse and enduring effects on children of witnessing domestic violence (James 1994; Mathias Mertin & Murray 1995; Kilpatrick & Williams 1997; Edelson 1999; Laing 2000; Tomison 2000; Indermaur 2001; Hume 2003). Similar to other Australian research into police responses to breaches of restraining orders (Egger & Stubbs 1993; Katzen 2002; Kearny McKenzie & Associates 1998), the Kaye et al. (2003) study found that police often did not enforce restraining orders if there were Family Court orders as state legislation was subject to federal legal provisions. Mothers who were opposed to contact because of continuing and repeated harm to themselves and their children were still obliged to ensure contact occurred.

The forgoing Australian research literature contests contemporary narrative constructions of resident mothers as the gatekeepers of child-father contact, in that resident mothers did not ordinarily exercise determinant control over the outcomes of contact disputes. The construct of the ‘contact denying’ mother appears to be

strongly embedded in the current legal frameworks which privilege child-father contact ahead of child and family safety. Mothers’ resistance to exposing their children to perceived continuing harm brought mothers experiencing violence and abuse into conflict with legal presumptions about ideal post-separation family relationships of continuing contact. The establishment of contact enforcement frameworks and continuing strengthening of compliance mechanisms provides a public policy process to invoke the identity of the ‘contact denying’ mother without addressing the rights to safety of abuse targets.

This research was aimed therefore at further empirically exploring the links between mothers’ attitudes to contact and experiences of violence, as well as the relationship between mothers’ attitudes to contact and actual contact practices. The analysis focuses on comparing the child-father contact attitudes and frequency of child-father contact for mothers who had experienced violence or abuse from the other parent with those who had not.

Method

The research approach included two preliminary focus groups followed by a survey. The focus groups were conducted to inform the development of the survey instrument. The survey was published on the internet at the beginning of October 2005 on the website of the National Council of Single Mothers and their Children1

and circulated on women’s email lists ‘solomothers,’ ‘SAWomen,’ ‘Ausfem-Polnet,’, ‘Womenspeak.’ Members of these lists were also invited to further circulate details about the survey across their networks. The survey was distributed in hardcopy format at the national conference of NCSMC and copies were posted to individuals and services who requested them. The services which distributed surveys to

1

Hereafter referred to as NCSMC. NCSMC is a federally funded peak body representing the interests of single mothers and their children to the benefit of all sole parent families. http://www.ncsmc.org.au

interested clients included family support services and women’s health and information services.

Sampling Process

The sampling process for the study was constrained by the absence of a representative random sampling frame for the population of resident separated mothers. The research sought to specifically include mothers from a varied range of separation experiences, including those who had issues with violence or abuse through to those who had separated amicably with no parenting disputes. The survey selection criteria were for separated resident mothers with majority care of a child under 18 and a father living elsewhere in Australia. Respondents could gain access to the survey by downloading it from the NCSMC website, by email, through services which chose to distribute it and by post on request. Survey returns were accepted from October 1 2005 until March 31 2006.

The sample is therefore variously drawn from mothers with access to the internet and mothers in contact with community based organisations providing services to single parents. As the sample draws on a self-selected group of resident mothers, the quantitative indicators cannot be generalised to the broader population of separated resident mothers. It is likely that the sample is biased towards mothers who have been unhappy with their post-separation parenting experiences, as they may have been more motivated to contribute to the research, compared with mothers who have had no concerns. The sample of 175 is however sufficiently large to

provide meaningful statistical analysis of the relationships between groups within the sample.

Comparative Analysis

The analysis sought to test whether there were significant differences in child-father contact attitudes and frequency of child-child-father contact between mothers who

experienced fear at separation or later, and those who did not. The survey data presented in this article therefore focuses on the end of the relationship and the post-separation arrangements for children.

About the Sample

The 175 analysed returns were predominantly from South Australia, with 40.1% from that state, followed by 19.2% from Victoria and 17.4% from New South Wales, 13.4% from Queensland, 5.2 % from Western Australia, 4.1 % from Tasmania and 0.6% from the Northern Territory. Only respondents with ex-partners living in Australia at the time of the survey were included.

Around one third of the sample (34%), were mainly reliant on income

support payments, 44% of mothers relied on wage income, and 22% combined wages and income support. Three-quarters of respondents reported receiving child

support. According to the mothers, 65% of their ex-partners derived their main income from employment, 15% received income support, 5% were self-employed, 13.5% didn’t know their ex-partner’s source of income, and the remainder received other income such as workers’ compensation.

Most mothers had one (36.6%) or two children (40.6%), 17% had three

children and the remainder had four or more children. The average age of the eldest child was ten (M= 10.6 SD 5.74).

The average period since separation was just under 4 years (M = 3.85 SD 2.03). Just over two-thirds of mothers (68.3 %) said they had ended the relationship, 18 % said the father had ended the relationship, 8.4 % said it had been a mutual decision and 5.4 % had not been in a relationship with the child’s father. Loss of relationship2 (n=120) and abuse3 issues (n= 117) were the most commonly nominated

2

‘Loss of relationship’ includes ‘communication breakdown’; ‘grew apart’; ‘infidelity’; differences about having children.

reasons for the end of the relationship, followed by health problems4 (n= 55) and work and other problems (n= 25).

Of the 175 respondents, two reported the children living in their father’s care at the time of separation and another 11 respondents said they shared the care. In the remaining 92.4% of cases, the children were in the mother’s care. Sixty-eight mothers said they had left and taken the children, and in 59 cases fathers had moved out, leaving the children in their mothers’ care.

Findings

Experiencing Fear

Sixty-two per cent of respondents reported being afraid of their ex-partner at the time of separation, declining to 42 % reporting continuing fear at the time of the survey. All of the respondents reporting fear had experienced some of a range of non-physical abusive behaviours including threats, verbal abuse, stalking, property damage, and litigation abuse. Half of the respondents reporting fear at separation had also experienced physical and or sexual abuse, 15 % also reported abuse of their children and 16 % indicated fathers with mental illness or substance abuse problems.

Mothers who reported fear at separation were significantly more likely to have left with the children5, comprising 78 % of the respondents who had taken this

action.

The sample was fairly evenly divided between mothers who had been

involved in Family Court proceedings (51%) and those who had not (49%). However when the mothers who experienced fear at separation were compared with those who had no fear issues, the former group were significantly more likely to be

3

‘Abuse’ includes physical /sexual/psychological /social/ financial abuse of mothers and/or children.

4

Health problems includes physical and mental health and substance abuse problems.

5

Cross tabulation Arrangements for Children at Separation by Fear at Separation. N= 169 Pearson Chi Square Value 17.47 df 6 p=.008

involved in court proceedings6, with 69.5 % of this group going to court, compared to

only 20 % of mothers who did not experience fear.

The data indicate that fear of the other parent was a significant driver of separation for many mothers, increasing the incidence of relationship breakdown, increasing the incidence of mothers’ decisions to leave with the children and increasing the need to use the Family Court to resolve disputes about parenting arrangements.

Mothers’ Attitudes to Child-Father Contact and Factors Affecting Contact Frequency

There were some significant differences in attitudes to child-father contact between mothers who experienced fear at separation and those who had not. Respondents were asked to rate their response to a number of statements on a five point scale (1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = neutral, 4 = agree and 5 = strongly agree). Table 1 indicates that mothers who had experienced fear had significantly less confidence that child-father contact would be a positive experience for their children.

6

Cross tabulation Involvement in Family Court proceedings by Fear at Separation. N= 169 Pearson Chi Square Value 38.531 df 1 p<.000

Table 1: Mothers’ Attitudes to Father-Child Contact by Experience of Fear at Separation Statement Fear at Separation No Fear t p M SD M SD Children still need both their parents after

separation

3.85 3.14 4.19 1.04 .831 .407

Children need to spend time with their father

3.5 1.18 4.23 0.9 4.24 3.7

My children are afraid of dad 2.87 1.28 1.76 1.08 -5.7 5.09

My children enjoy contact with dad 3.33 1.3 3.92 1.13 2.97 .003 I look forward to having a break during

contact visits 3.21 1.25 3.77 1.21 2.94 .004

I am always worried about my children

when they are with dad 3.69 1.25 2.98 1.00 -3.5 .000 My children know dad will always be there

for them

2.31 1.07 2.79 1.36 2.49 .014

N = 175 Descriptive Statistics Independent T-Test

As the responses to the first three statements indicate, most mothers were generally positive towards child-father contact in principle, with no significant variation between the group who reported experiencing fear and those who did not. Most mothers disagreed with the statement ‘My children are afraid of dad’, however mothers who had never experienced fear of their ex-partner were significantly more likely to agree that their children enjoyed contact with dad. Mothers who had experienced fear at separation were significantly less confident that their children were safe and happy in their father’s care. The qualitative survey data indicate that even fearful mothers were commonly initially optimistic about their children’s relationship with their father. This view changed when children experienced distress or disclosed abuse during child-father contact.

Despite the variations in mothers’ attitudes towards child-father contact, there was no significant difference in actual patterns of contact linked to fear at separation. Across the sample just over 60 % of mothers reported fortnightly or more contact, regardless of whether they were fearful of their partners at separation (Table 2).

Table 2: Contact Patterns and Mothers’ Fear Status at Separation Contact Pattern Fear at

Separation No Fear Total

N % N % N %

Fortnightly or more 69 40.8 44 26 113 66.9

Monthly or Less 21 12.4 11 6.5 32 18.9

No Contact 15 8.9 9 5.3 24 14.2

Total 105 62.1 64 37.9 169 100

N= 175 Missing = 6 Pearson Chi-Square Value .222 df 2 p=.895

While it seems that mothers’ fear made them more concerned for their children’s safety during contact, these attitudes did not translate into reduced frequency of contact. Differences in contact frequency were also not significantly related to participation in Family Court proceedings7.

The distance between households was however significantly associated with the frequency of contact. As Table 3 shows, all but four of the fathers taking

fortnightly or more contact lived within 200 kilometres of their children, whilst around half of the fathers having no contact lived more than 200 kilometres away.

A comparison of the distance between parents’ households between mothers who experienced fear at separation and those who did not showed no significant

7

Cross Tabulation Contact Pattern by Family Court Proceedings N=175 Missing = 5 Pearson Chi-Square Value .403 df 2 p=.818

variation between the groups8. This is unsurprising given that relocation orders can

be used to constrain the resident parents’ choice of residential location. Table 3: Contact Patterns and Distance from Father

Contact Pattern Less than

200k More than 200k Whereabouts Unknown Total

N % N % N % N %

Fortnightly or more 104 64.2 3 1.8 1 0.6 108 66.6

Monthly or Less 16 9.9 13 8.0 2 1.2 31 19.1

No Contact 9 5.5 11 6.8 3 1.8 23 14.1

Total 129 79.6 27 16.7 6 3.7 162 100

N=175 Missing = 13 Pearson Chi-Square Value 57.635 df 4 p<.001

High work demands (n=50) and health problems (n=43) were other factors nominated by around one in four mothers as limiting the fathers’ availability for contact.

Stopping Planned Contact

The survey also sought data on disruptions to planned contact in the 12 months prior to the research. Forty-two mothers (24%) indicated they had stopped planned contact. Of these, 17 had stopped contact once in that time, 15 had stopped contact between two and four times, whilst six had stopped contact on more than four occasions. The reasons given for stopping contact were child safety (n=15), child illness (n=11), child sporting or social or other commitment (n=8) and child resistance (n=7).

8

Cross Tabulation Distance from Father by Fear at Separation N=175 Missing = 15 Pearson Chi-Square Value 1.009 df 2 p=.604

Eighty-one mothers (46%) indicated that fathers had stopped planned contact in the 12 months prior to the survey. Of these 8 had stopped contact once, 31 had stopped contact between two and four times and 29 had stopped contact on more than four occasions. The most common reason given by mothers for the fathers’ cancellation of contact was apparent lack of interest (n= 24), social relationships and holidays (n=17), health reasons (n=13), work demands (n=12) and lack of money (n=3). The accuracy of the reasons mothers gave for fathers’ actions in stopping planned contact was necessarily limited by their knowledge of his circumstances and decisions.

Managing Contact

Respondents mainly conducted contact handover at their residence (n=86) or the father’s residence (n=45), followed by school or child-care (n=33), a safe public place such as McDonalds (n= 24), at a children’s contact centre (n=16) or a police station (n=5). Mothers who experienced fear at separation were significantly more likely to use a children’s contact centre9 or McDonalds10 compared to other mothers.

Use of contact centres is constrained by the number and location of centres, the level of demand for such services, the cost of the service, both parents’ willingness to use these centres and the willingness of the centre to provide the service. As noted in the literature (Sheehan et al. 2005), children’s contact centres also withdrew services when they considered that a parent was too dangerous. Consequently the most dangerous contact arrangements must be managed by victims without access to professional help or protection.

9

Cross Tabulation Fear at Separation by Use of Child Contact Centre for Handover n=22 Pearson Chi Square Value =11.81 df 2 p=.003

10

Cross Tabulation Fear at Separation by Use of McDonalds for Handover n=29 Pearson Chi Square Value =.243 df 1 p=.039

Mothers’ Perceptions of Children’s Current Relationship with their Father

Mothers who experienced fear at separation assessed their children’s current general relationship with their father more negatively than other mothers.

Respondents were asked to rate their perception of aspects of their children’s current relationship with their father on a five point scale (1= very bad, 2 = poor, 3 = neutral, 4 = good and 5 = very good).

Table 4: Mothers’ Perceptions of Children’s Contact and Relationship with Father Mothers’ perceptions of Children’s

Contact and Relationship with Father Fear at Separation

No Fear

t p

M SD M SD Overall quality of child-father

relationship

3.04 1.136 3.56 1.14 2.828 .005

General Communication between child

and father 2.66 1.1 3.07 1.25 2.178 .03

Emotional well-being and safety of child

with father 2.43 1.043 3.21 1.217 4.347 2.46

Physical well-being and safety of child with father

2.78 1.064 3.52 1.127 4.215 4.197

N = 175 Descriptive Statistics Independent T-Test

As Table 4 shows, mothers who had been fearful had a generally more negative view of the father’s current relationship with their children, whereas other mothers assessed these relationships more positively. Given that the average duration since relationship breakdown was four years, the mothers’ experiences of fear had an apparently enduring impact on their assessments of the children’s relationship with their father.

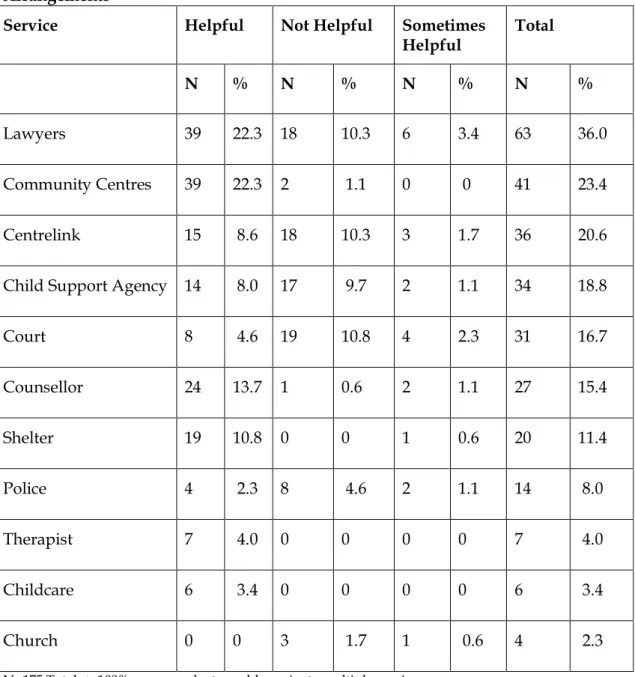

Respondents were also asked to nominate the services which they had found most helpful and least helpful in making post-separation parenting arrangements. Respondents could nominate as many services as they wished.

Table 5: Mothers’ Views of Most Helpful and Least Helpful Services for Parenting Arrangements

Service Helpful Not Helpful Sometimes

Helpful Total

N % N % N % N %

Lawyers 39 22.3 18 10.3 6 3.4 63 36.0

Community Centres 39 22.3 2 1.1 0 0 41 23.4

Centrelink 15 8.6 18 10.3 3 1.7 36 20.6

Child Support Agency 14 8.0 17 9.7 2 1.1 34 18.8

Court 8 4.6 19 10.8 4 2.3 31 16.7 Counsellor 24 13.7 1 0.6 2 1.1 27 15.4 Shelter 19 10.8 0 0 1 0.6 20 11.4 Police 4 2.3 8 4.6 2 1.1 14 8.0 Therapist 7 4.0 0 0 0 0 7 4.0 Childcare 6 3.4 0 0 0 0 6 3.4 Church 0 0 3 1.7 1 0.6 4 2.3

N=175 Totals > 100% as respondents could nominate multiple services

Table 5 displays the services nominated in descending frequency of

nomination. Whilst lawyers were the most frequently nominated service, community centres, counsellors, shelters, therapists and childcare services were seen by mothers as the most helpful. Centrelink, the Child Support Agency, the courts, police and churches were seen as not helpful, or only helpful sometimes, by those who indicated they had used them.

Discussion

The data confirm the significance of fear in shaping separated resident mothers’ attitudes to father-child contact. The mothers who had been afraid at separation were more likely to leave the relationship and take the children, to engage in court processes and to worry about their children’s safety and well-being during child-father contact. These mothers were also significantly more likely to use a contact service or public handover place for contact and to negatively assess the father’s current relationship with their children.

The data showed no significant relationship between mothers’ fear at

separation and the frequency of contact. The frequency of contact was also unrelated to involvement in court proceedings. Rather contact frequency was significantly associated with the distance between homes and the fathers’ availability for contact, Fathers living more than 200 kilometres from their children had less frequent contact. Mothers who experienced fear at separation were no more or less likely to live within 200 kilometres of the child’s father. The parent the child lives with does not exercise determinant control over relocation if the other parent opposes it through the courts. Only non-resident parents can freely choose the distance they live from their children after separation.

Just under one in four mothers admitted stopping planned contact in the 12 months prior to the survey, with most stopping contact only once or twice with the most common reasons relating to child safety and child illness. Respondents

reported that twice as many fathers, just under half the sample, had stopped planned contact. Mothers’ reports of fathers not taking planned contact may reflect the

identified in previous research (Smyth, Caruana & Ferro 2004). Mothers regard fathers to be opting out when they fail to take planned contact, while fathers claim they are refused contact when they fail to take planned contact. The data tends to support the proposition that non-resident fathers’ choices about their location and availability for contact are more significant than mothers’ attitudes in determining whether contact takes place.

Mothers used a wide range of services in managing contact and seeking support with post-separation parenting arrangements. It is notable that the

government agencies dealing with separated parents, such as Centrelink, the Child Support Agency, The Family Court and Federal Magistrates Courts, were generally regarded as unhelpful by a majority of mothers who said they had used their services. This may indicate a disjuncture between some mothers’ expectations of services and the ways in which services responded. Mothers who ended a relationship with a violent or abusive partner in the expectation of keeping themselves and their children safe are commonly unable to prevent child-father contact if it is sought and taken by fathers.

The data indicates the limitations inherent in focusing only on resident parents as being responsible for contact taking place. Resident parents are held responsible at law to make children available for contact under parenting plans or court orders, yet they are also deemed responsible for contact parents’ failures to take contact. The 2006 changes to family law introduced an increased range of penalties for resident parents who fail to comply with Parenting Orders.

Non-resident parents retain discretion over whether they choose to take the time allocated for them to spend time with their children.

The self-selecting sampling process of this study limits the generalisation of the data across the population of separated resident mothers, however the key issues identified by mothers in this study have been present in previous research.

Conclusion

The objectives of the research were to:

identify the attitudes of separated resident mothers to child-father contact, identify the factors which had informed mothers’ attitudes,

explore how mothers’ attitudes impacted on child-father contact frequency. The survey data identified that separated resident mothers were generally strongly supportive of fathers maintaining contact with their children after

separation. Mothers who had experienced fear at separation were likely to express more negative attitudes to child-father contact and the child’s current relationship with their father, but these attitudes did not determine the frequency of contact in this sample of resident mothers. Mothers who were afraid of their ex-partner and afraid for their children’s safety were compliant with court orders and agreements in most instances. When mothers did stop contact, children’s safety and health were the main reasons and most stopped contact only once or twice. Fathers’ desires to see their children and their availability for contact had a much greater impact on whether contact took place, with mothers reporting twice as many fathers cancelling or not attending planned contact.

The research findings signal the inadequacy of contemporary family law approaches to post-separation parenting which construct resident mothers as withholders of contact and fathers as the passive victims of biased family law and women’s ‘vengeful’ practices (Kaye & Tolmie 1998, 1998a).

The July 2006 changes enshrine children’s right to a meaningful relationship with both parents and their right to be protected from violence or abuse, but fail to address or resolve the risks to child safety articulated in the Family Law Council’s report on child protection in family law (2002). The re-definition of ‘a child’s best interests’ as shared parental responsibility places mothers and children leaving violent or abusive relationships in the routine position of proving harm they have previously experienced in a context where access to police and child protection services is often highly variable (Kaspiew 2005; Katzen 2000), and family law decision-makers can disregard state Apprehended Violence Orders and child protection substantiations.

Mothers’ high levels of support for safe child-father contact should be publicly recognised and valued. Where parents raise protective concerns, decision-makers should be required to privilege child safety, underpinned by a robust investigative process and a zero tolerance approach to family violence.

REFERENCES

Altobelli, T., (2000) ‘Recent developments in Interim Residence Applications: Back to the Future?’, Australian Journal of Family Law, 14:36-64.

Attorney General’s Department (2003) Submission to the House of Representatives Standing Committee on Family and Community Affairs Inquiry into Child Custody Arrangements in the Event of Family Separation, Canberra, Attorney General’s Department.

Attorney General’s Department (2005) Explanatory Memorandum Family Law

Amendment Shared Parental Responsibility) Bill, Canberra, Attorney General’s Department.

Australian Bureau of Statistics, (2003) Divorces Australia, Catalogue Number 3307.055.001 Canberra, AGPS.

Australian Bureau of Statistics, (2004) Family Characteristics Australia, Catalogue Number 4442.0, Canberra, AGPS.

Brown, T., Frederico, M., Hewitt, L., and Sheehan, R., (1998) Violence in Families Report Number One: The Management of Child Abuse Allegations in Custody and Access Disputes before the Family Court of Australia, Monash University Clayton, The Family Violence and Family Court Research Program Monash University Clayton and the Australian Catholic University, Canberra.

Brown, T., Frederico, M., Hewitt, L. and Sheehan, R., (2001) ‘The Child Abuse and Divorce Myth’ Child Abuse Review, 10: 113-124.

Brown, T., Sheehan, R., Frederico, M., and Hewitt, L., (2001a) Resolving Family Violence to Children: The Evaluation of Project Magellan, a pilot project for managing Family Court residence and contact disputes when allegations of child

abuse have been made. Monash University Clayton, The Family Violence and Family Court Research Program.

Byas, A., (2000) ‘Post-separation Parenting - what’s law got to do with it?’ 7th AIFS Conference, Sydney, 24-26 July.

Cass, B., (1988) ‘The Feminization of Poverty’, in B. Caine, E. Grosz and M. de Lepervanche, (eds) Crossing Boundaries, Sydney, Allen and Unwin :110-128. Child Support Agency (2003) Child Support Scheme Facts and Figures 2002-03,

Canberra, Child Support Agency.

Coleman, M., Ganong, L. Killian, T. and McDaniel, A., (1998) ‘Mom’s House? Dad’s House? Attitudes Toward Physical Custody Changes’, Families in Society: The Journal of Contemporary Human Services, 79 (2): 112-122.

Craig, L. (2003) ‘Do Australians Share Parenting? Time Diary Evidence on fathers’ and mothers’ time with children’ 8th AIFS Conference February, Melbourne.

Czapanskiy, K., (1991) ‘Volunteers and Draftees: The Struggle for Parental Equality’, UCLA Law Review, 38: 1415-81.

Dewar, J. and Parker S., (1999) ‘The Impact of the New Part VII Family Law Act 1975’, Australian Journal of Family Law, 13:96-116.

Edelson, J., (1999) ‘Children’s Witnessing of Adult Domestic Violence’ Journal of Interpersonal Violence, Vol. 14, No. 8, August pp. 839-870.

Egger, S. and Stubbs, J., (1993) The Effectiveness of Protection Orders in Australian Jurisdictions, Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet, Office of the Status of Women National Committee on Violence Against Women, Canberra, AGPS.

Family Court of Australia, (2003), Submission to the House of Representatives Standing Committee on Family and Community Affairs Inquiry into Joint Custody

Arrangements in the Event of Family Separation, Family Court of Australia, Melbourne.

Family Law Council, (1998) Interim Report Child Contact Orders: Enforcement and Penalties, Canberra, AGPS.

Family Law Council, (1998a) Child Contact Orders: Enforcement and Penalties, Canberra, AGPS.

Family Law Council (2002) Family Law and Child Protection, Canberra, AGPS.

Family Law Council (2004)

Family Law Council: Review of Division 11 – Family

Violence,

Letter of Advice to the Attorney General, Canberra.

Family Law Pathways Advisory Group, (2001) Out of the Maze, Canberra, Attorney Generals Department.

Fehlberg, B., and Kelly, F., (2000) Jurisdictional Overlaps: Division of the Children’s Court of Victoria and the Family Court of Australia, Australian Journal of Family Law, 14 (3): 211-233.

Flood, M. (2004) ‘Backlash: Angry Men’s Movements’, in E. E. Rossi (Ed.) The Battle and Backlash Rage on: Why Feminism Cannot be Obsolete, USA. Xlibris

Corporation.

Harrison, M., (1992) ‘Child Support Reforms and Post-Separation Parenting: Experiences and Expectations’, Australian Journal of Family Law, 6 (1):22-31.

House of Representatives Standing Committee on Family and Community Affairs (2003) Every Picture Tells a Story: Inquiry into Child Custody Arrangements in the Event of Family Separation, Canberra, Commonwealth of Australia.

Hume, M., (1996) Child Sexual Abuse Allegations and the Family Court of South Australia, Masters Thesis: University of South Australia.

Hume, M., (2003) The Relationship between child sexual Abuse, Domestic Violence and Separating Families, Child Sexual Abuse: Justice Response or Alternative Resolution Australian Institute of Criminology, Adelaide May 1-2.

Humphreys C., (1999) ‘Walking on eggshells: Child sexual abuse allegations in the Context of Divorce’, in J. Breckenridge and L. Laing, (eds) Challenging Silence: Innovative Responses to Sexual and Domestic Violence, Sydney, Allen and Unwin.

Indermaur, D., (2001) Young Australians and Domestic Violence, Trends and Issues Paper No. 195, Canberra, Australian Institute of Criminology.

James, M., (1994) Domestic Violence as a form of Child Abuse: Identification and Prevention, Issues in Child Abuse Prevention Number 2. National Child Protection Clearinghouse, AIFS Melbourne.

Kaganas, F. and Sclater, S. (2004) ‘Contact Disputes: Narrative Constructions of ‘good’ parents’, Feminist Legal Studies, 00: pp. 1-26, Netherlands, Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Kaspiew R. (2005) Violence in Contested children’s cases: An empirical exploration,

Australian Journal of Family Law Vol. 19 No. 2 pp 112-143.

Katzen, H., (2000) ‘It’s a Family Matter, not a Police Matter: The Enforcement of Protection Orders’, Australian Journal of Family Law, 14 (2):119-141.

Kaye, M., and Tolmie, J., (1998) ‘Discoursing Dads: The Rhetorical Devices of Fathers’ Rights Groups’, Melbourne University Law Review, 22 (1): 162-194.

Kaye, M., and Tolmie, J., (1998a) ‘Fathers’ Rights Groups in Australia and their Engagement with Issues in Family Law’, Australian Journal of Family Law, 12 (1):19-67.

Kaye, M., Stubbs, J. and Tolmie, J. (2003) Negotiating Child Residence and Contact Arrangements against a Background of Domestic Violence, Families, Law and Social Policy Research Unit, Griffith University, Queensland.

Kearney McKenzie & Associates (1998) Review of Division 11: Review of the operation of Division 11 of the Family Law Reform Act to resolve inconsistencies between State family violence orders and contact orders made under family law. Canberra, Office for the Status of Women, Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet.

Kelly, F. and Fehlberg, B., (2002) ‘Australia’s Fragmented Family Law System: Jurisdictional Overlap in Child Protection, International Journal of Law, Policy and the Family, 16: 38-70.

Kilpatrick, K., and Williams, L., (1997) ‘Post Traumatic Stress Disorder in Child Witnesses to Domestic Violence’, American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 67 (4): 639-644.

Lavarch, M., (1994) Family Law Reform Bill 1994: Explanatory Memorandum,

Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia, Catalogue Number 9447236, Canberra, AGPS.

Laing, L., (2000) Children, Young People and Domestic Violence, Australian Domestic and Family Violence Clearinghouse Issues Paper 2, Sydney, Partnerships against Domestic Violence, University of New South Wales.

McInnes, E., (2001) ‘Public Policy and Private Lives: Single Mothers, Social Policy and Gendered Violence’, Thesis Collection, Flinders University of SA.

http://www.ncsmc.org.au/phd

McInnes, E., (2003) Parental Alienation Syndrome: A Paradigm for Child Abuse in Australian Family Law, Child Sexual Abuse: Justice Response or Alternative Resolution Australian Institute of Criminology, Adelaide May 1-2.

McInnes, E., (2004) The Challenges of Securing Human Rights to Safety in Australian Family Law Frameworks, paper presented at Home Truths Conference , Melbourne September 15-17.

Mathias, J., Mertin, P., and Murray, A. (1995), ‘The Psychological Functioning of Children from Backgrounds of Domestic Violence,’ Australian Psychologist, Vol. 30, No.1, March, pp. 47-56.

Moloney, L., (1998) ‘Do Fathers ‘win’ or do mothers ‘lose’? A Preliminary analysis of a random sample of parenting judgements in the Family Court of Australia’, 6th AIFS Conference, Melbourne: November 27-28.

Mouzos, J. and Segrave , M., (2004) Homicide in Australia: 2002-2003 National

Homicide Monitoring Program (NHMP) annual report, Australian Institute of Criminology, Canberra.

Parkinson, P., (2002) ‘Parenthood and the Impossibility of Divorce, Paper to the Australian Institute of Family Studies Conference June, Melbourne.

Parkinson, P., and Smyth, B., (2003) ‘When the Difference is Night and Day: Some Empirical Insights into Patterns of Parent Child Contact After Separation’, Paper presented at the 8th AIFS Conference, Melbourne February 12-14.

Rendell, K., Rathus, Z. and Lynch, A., (2000) An unacceptable risk: A Report on child contact arrangements where there is violence in the family, Brisbane, Women’s Legal Service.

Rhoades, H., (2000) ‘Posing as Reform: The case of the Family Law Reform Act’, Australian Journal of Family Law, 14 (2): 142-159.

Rhoades, H., (2002) ‘The ‘No Contact’ Mother: Reconstructions of Motherhood in the era of the ‘New Father’, International Journal of Law, Policy and the Family, 16 (1): 71-94.

Rhoades, H., Graycar, R., and Harrison, M., (1999) The Family Law Reform Act 1995: Can changing legislation change legal culture, legal practice and community expectation? Interim Report, Sydney, University of Sydney and the Family Court of Australia.

Rhoades, H., Graycar, R., and Harrison, M., (2001) The Family Law Reform Act 1995: The First Three Years, Final Report, Sydney, University of Sydney and the Family Court of Australia.

Shaver, S., (1988) ‘Sex and Money in the Welfare State’, in C. Baldock and B. Cass, (eds) Women, Social Welfare and the State, Sydney, Allen and Unwin.

Sheehan, G., Carson, R., Fehlberg, B., Hunter, R., Tomison, A., Ip, R., Dewar, J., (2005) Children’s Contact Services: Expectations and Experiences, Brisbane, Griffith University Socio-Legal Research Centre.

Smyth, B. (ed.) (2004), Parent-Child Contact and Post Separation Parenting

Arrangements, Research Report No. 9, Melbourne, Australian Institute of Family Studies.

Smyth, B., Caruana, C. and Ferro, A. (2004) ‘Child-father contact after separation’, Family Matters, No. 67: 20-27.

Smyth, B., Qu, L. and Weston, R. (2004), The Demography of Parent-Child Contact, in B. Smyth (Ed.) Parent-Child Contact and Post Separation Parenting

Arrangements, Research Report No. 9, Melbourne, Australian Institute of Family Studies.

Smyth, B., Sheehan, G. and Fehlberg, B., (2001) ‘Patterns of Parenting after Divorce: A pre-Reform Act Benchmark Study, Australian Journal of Family Law, Vol. 15, No. 2, pp. 114-128.

Smyth, B. and Weston, R. (2004) ‘The attitudes of separated mothers and fathers to 50/50 shared care, Family Matters, No. 67: 8-15.

Smyth, B. and Wolcott, I., (2004), ‘Why Study Parent-Child Contact?’ in B. Smyth (ed.) Parent-Child Contact and Post Separation Parenting Arrangements, Research Report No. 9, Melbourne, Australian Institute of Family Studies.

Tomison, A., (2000) ‘Exploring family violence: Links between child maltreatment and domestic violence’, Issues in Child Abuse Prevention, 13: Winter, National Child Protection Clearinghouse, Melbourne, Australian Institute of Family Studies.

Wallbank, J., (1998) ‘Castigating Mothers: the judicial response to ‘wilful’ women in disputes over paternal contact in English law’, The Journal of Social Welfare and Family Law, 20 (4):357-376.