DOMINANT MECHA NISMS FOR PROJECT

PORTFOLIO MANAGEMENT IN

PRACTICE

STUDEN T: J . H. VAN EN K SUPERVI SO R: T.M . VAN ENGERS

DATE: 30- 6- 2014 VERSION: 1.0

ABSTRACT

THI S THE SI S PRESE NT S T HE DO MI NA NT ME CHANI S MS I N ORGA NI SAT IONS FO R PRO JE CT PORTFOLIO MANAGE MENT IN P RA CT ICE , DE RI VE D FROM A ‘CRI TI CA L CA SE’ CA SE ST UDY . A GOVERNMENTA L ORG ANIS ATIO N’ S EFFORTS TO I MP LEME NT A PRO JE CT P ORT FOLIO PRO CES S HAV E

BEEN EXA MI NE D BY MEA NS OF ST AKE HOLDE R A N A LYSE S, PA RT I CIPA NT OB S ERV ATIO N A ND A WORKS HOP. T HE RES ULT S LEA D TO THE I DE NTI F I CA TIO N OF ELEME NT S FOR A FOUND A TIO N THAT

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This thesis could not have been realized without the guidance of both the supervisor from the University and the supervisor from the municipality. I want to express my gratitude to Prof. T.M. van Engers for his support, encouragements and valuable comments and suggestions in the research process.

Furthermore I want to sincerely thank MSc. H. Toprak for teaching me valuable lessons about dealing with, and being part of, a big organization, and for giving me the opportunity to participate in the organisation.

Last but not least, I want to thank my family and friends for encouraging me all these years to get to the point of obtaining my Masters degree. Their support, advice and companionship helped me persevere at even the toughest moments.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Abstract ... 1 Acknowledgements ... 2 List of figures ... 4 List of abbreviations ... 4 Introduction ... 5Portfolio Management’s formal role ... 5

Portfolio management social dynamics ... 6

Introduction to Case Study ... 7

Methods ... 9

Framework for Project Portfolio Management ... 9

Interviews ... 9

Participant Observation ... 10

Workshop ... 10

Results ... 11

Framework Project Portfolio Management ... 11

Stakeholder Analysis ... 12

Social dynamics ... 14

Workshop Results ... 14

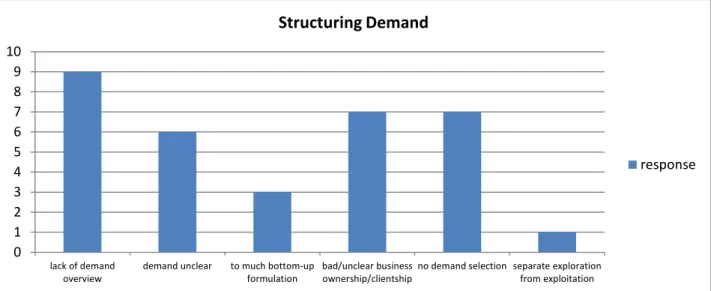

Structuring Business Demand ... 15

Balance/Categorising ... 15

Prioritizing ... 16

Control ... 16

Plotting observations on the PPM framework ... 17

Conclusion ... 18

Discussion ... 20

References ... 21

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure 1: case study Organisation ... 8

Figure 2: Interviewee positions in organisation ... 9

Figure 3: representation of workshop method ... 10

Table 1: Structuring demand ... 15

Table 2: Balance/Categorize ... 15

Table 3: Prioritize ... 16

Table 4: Control ... 16

Table 5: Plot of observations on framework ... 17

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

IBS Informatie Beleid en Strategie

IBO Informatie Beheer en Ontwikkeling

MI Management Informatie

BV Bedrijfsvoering

SZW Sociale Zaken en Werkgelegenheid

PPM Project Portfolio Management

PMO Project, Program and Portfolio Management Office1

INTRODUCTION

Project portfolio management (PPM) has developed into a major concept in today’s organisations. Its uses are widely known and supported by scientific literature (Cooper, Edgett, & Kleinschmidt, New problems, new solutions: making portfolio management more effective., 2000). Despite its widespread use however, many organisations struggle with the implementation of their own project portfolio and with embedding the portfolio management (office) as a role in the organisation. Few research has been conducted in this area because the majority of research focusses on the formal roles of project portfolio managers, and on project portfolio success. Project portfolio success however, can only be examined if a more or less stable portfolio management role has been established. The establishment of PPM in an organisation will be examined in depth in this research because this proves to be difficult. The examination of formal roles in portfolio

management does not provide insight in the problems that arise in organisations when a project portfolio needs to be built from the ground up.

In this thesis I will first introduce PPM in its formal role and the social dynamics that are involved. Accordingly, I will describe the case study of a large Dutch municipality’s implementation of PPM. A constitution of the project portfolio as a concept and process will be provided in order to clarify what elements should be assessed in organisations. Accordingly, an analysis of the stakeholders in the organisation that struggles in implementing portfolio management will be provided. The analysis will denude the organization's’ specific causes for PPM implementation difficulties. Finally the conclusion will answer the research question: “What are the dominant mechanisms of PPM in practice?”.

PORTFOLIO MANAGEMENT’S FORMAL ROLE

Multiple definitions of a project portfolio and the management theirof have been introduced in literature in recent years. A project portfolio is “a collection of projects, programs and other work that is managed jointly for the achievement of the business objectives” (Beetsma, 2011). The management of a portfolio is “a coordinated collection of strategic processes and decisions that together enable the most effective balance of organizational change and business as usual” (Great, 2008), and this definition will be continued in this thesis.

Much research has been conducted in the area of PPM evaluation dimensions (Martinsuo &

Lehtonen, Role of single-project management in achieving portfolio management efficiency, 2007), (Platje, Seidel, & Wadman, 1994). Recent literature highlights the importance of project portfolio management in evaluating, prioritizing and selecting projects in line with strategy. However, no study exists on a framework covering the whole cycle from strategic planning via project portfolio management to business success (Meskendahl, 2010). A literature study conducted on project portfolio management dashboards indicates that project prioritization is an important aspect of PPM, yet literature until now does not propose standardized processes for this.

As one of the most important aspects of project portfolio management is the selection, or prioritization, of projects, it is surprising to find that few methods for (IT) project

prioritization have been proposed in literature. Several prioritization methods exist in other fields such as finance. Efforts have been made to translate these methods to other fields, but no widely accepted method exists. (van Enk, Everaert, Lammertink, Notenboom, & Pattynama, 2014)

Studies (Cooper, Edgett, & Kleinschmidt, Best practices for managing R&D portfolios., 1998), (Cooper, Edgett, & Kleinschmidt, New problems, new solutions: making portfolio management more effective., 2000) show that effective portfolio management is difficult to achieve for many companies. Although some of the challenges presented in existing research find their cause in project management, they affect the project portfolio nonetheless. No widely accepted solution for these challenges has yet been proposed, and this research is not an endeavor to do so either. The challenges will be studied in order to identify relations between the challenges and human relationships (either personal, or professional).

The identification of a possible gap between theory, which is based on ideal worlds or environments, and practice in which human relations play a significant role in the way (even formalized) project portfolio management is situated. The challenges introduced above will be studied in order to identify relations between the challenges and human relation (either personal, or professional). Moreover, project portfolio offices differ in their role in different organizations (Unger, Gemünden, & Aubry, The three roles of a project portfolio management office: Their impact on portfolio management execution and success, 2012). The hypothesis that the nature of project portfolio offices’ role in an organization depends (partially) on the nature of the influence field dynamics within that organization will be investigated. Relations between different stakeholders will be investigated, focussing on the dimensions of formal role and underlying

incentive/motivation to act in certain ways. Of course numerous other dimensions exist, but they will not be in the scope of this research.

PORTFOLIO MANAGEMENT SOCIAL DYNAMICS

Jonas (Jonas, 2010) addresses this gap by describing three key manager roles (line management, project portfolio management, and top management) and the influence of their interrelationships on the project portfolio. However, the key role of project manager has been left out of his research due to complexity reasons. In this thesis the complexity of the social field will be higher because a wide range of portfolio stakeholders will be considered. Case study research is suitable in this situation because theory building from case studies does not rely on previous literature or prior empirical evidence (Eisenhardt, 1989). The field of social dynamics in project or portfolio management context has not been explored by many scientists yet. Jonas(Jonas, 2010)and

Martinsuo (Martinsuo, Project portfolio management in practice and in context, 2013) can be seen as one of the first to address practical issues in organisations concerning PPM, although they do not focus on the implementation of PPM, but rather on already established PPM processes in

organisations. Much can be learned from social studies in organisations with no specific regard for project management.

INTRODUCTION TO CASE STUDY

A large Dutch municipality will be the subject of an extensive case study. In this in-depth case study, the social dynamics between actors that are somehow involved in the project portfolio of the municipality’s social services department will be investigated. This will yield a social dynamics influence field that will be composed using a method applied in the article “Knowledge Based Influence Field Dynamics” (Schreinemakers & van Engers, 2007) method. The case study

organisation structure is displayed in figure 1. “Concern” is the municipality in question. It works together with three other large municipalities. The four municipalities are referred to as “G4”. In the specific concern, a large department is called “Dienst SZW”. This department has numerous

(clusters of) units. For each cluster a “Directeur” is responsible. “Directie Bedrijfsvoering” is one of these clusters, and consists of clusters itself. The IT cluster’s major unit is the Information Policy and Strategy unit. This unit is attempting to install a project portfolio, and to develop a business process that enables them to manage this project portfolio.

The case study is a so called critical case (Flyvbjerg, 2006), because the organisation is a representative municipality in which PPM is being implemented at the time of this research. Moreover, the mechanisms to be encountered in the case study organisation will be comparable to the ones encoutered in a large range of organisations, or at least municipalities.

FIGURE 1: CASE STUDY ORGANISATION

METHODS

A baseline (framework) for PPM will be provided on which case study observations will be plotted. A validation of the observations will be provided by means of a workshop session at the

municipality. The comparison between observations and the baseline will clarify what kind of measures are required in order to reach successful PPM implementation in an organisation.

FRAMEWORK FOR PROJECT PORTFOLIO MANAGEMENT

A framework for PPM has been defined in order to provide a basis for comparison. Literature will provide the basis for this framework, but a connection to the case study organisation is made as well. Problems that are defined throughout the research are plotted onto this framework in order to gain insight in relations and dependencies between problems. Moreover, solutions that are proposed for each problem can be put in perspective of this framework. “Would this solution eliminate the problem in the framework?”.

INTERVIEWS

Interviews have been conducted with middle management throughout the department of the case study object. Business management represents the demanding stakeholder (“client”) in the project portfolio, while IT management represents the chain of stakeholders that meet these business demands by means of (technical) IT supply management.

While the formal roles of project portfolio stakeholders are easily identifiable, their (in)formal relations and intentions are not. The conducted interviews are used to construct a stakeholder analysis in which these relationships become clear. The stakeholder analysis should provide insight in the social dynamics between units in the department and the personal relationships among middle management. Figure 2 shows the interviewees positions within the organisation. Each blue box is a person and formal role that has been interviewed.

PARTICIPANT OBSERVATION

Participant observation is used as a data collection method. This is an effective method for obtaining detailed descriptions of behaviors, intentions, situations and unscheduled events (Kawulich, 2005). Numerous meetings of various compositions of stakeholders and with different goals have been attended. These meetings provide insight in the formal and informal interaction between stakeholders. Combined with the interaction on the workfloor, these observations provide an additional perspective on the PPM implementation process in the organisation.

WORKSHOP

The unit providing the project managers, architects and IT-advisors are the key stakeholders of the project portfolio. Therefore they are involved in (but not necessarily accountable for) all identified problems in the PPM process. The workshop will provide insight in the self image of the project managers, IT-architects and IT-advisors regarding these problems. The results of the workshop will serve as a validation of the observed problems as well as a validation of the results extracted from the interviews.

A one hour session was booked for the workshop, which ten employees attended. The purpose and procedure of the

workshop were explained. The employees were asked to write down any problems they perceived on post-its. Four elements in the PPM were discussed separately. Each element was first briefly defined by the workshop leader, after which the employees were asked to write on post-it’s any problems they perceived in the specified element when looking at their organisation. The post-it’s, each containing one problem, were put on a flip-over page and clustered by the workshop leader, resulting in sheets configured as the one in figure 3.

A short discussion on the two or three most frequently named problems was held in which employees could clarify their opinion and opposite opinions would be underpinned. After each discussion the next element would be introduced. A short evaluation of the workshop by the

FIGURE 3: REPRESENTATION OF WORKSHOP METHOD

RESULTS

FRAMEWORK PROJECT PORTFOLIO MANAGEMENT

Seven elements compose the framework for PPM that has been constructed from literature. These seven elements do not specifically describe chronological elements in the PPM process. Each element is a process in itself, and these processes together form the PPM process. Crucial in the PPM process is the distribution of responsibilities among formal roles in the organisation. Understand

PPM is a continuous process that entails more than the altering and guarding of the project portfolio. While the project portfolio is in principle only a list of projects on which resources are presently allocated, often a separate list of pending project proposals exists. This list of project proposals should only contain proposals that have a valid business case (Gutiérrez & Magnusson, 2014). Valid business cases contain clear budget and capacity planning, clear products and deadlines, and clear risk descriptions. Business demand forecasting is done by the IT units in cooperation with business owners.

Categorize

The project proposals have to be linked to a part of the vision or strategy. This will give insight in the distribution of projects across the organisation’s goals (Hughes, 2007), (Meskendahl, 2010), (de Reyck, Grushka-Cockayne, Lockett, Calderini, Moura, & Sloper, 2005).

Prioritize

The project proposals are assessed on predefined criteria. This assessment will result in a ranked list of projects. Assessment criteria are:

● Anticipated realisation of vision and strategy ● Cost saving (long term)

● Anticipated customer satisfaction ● compliancy (urgence)

● risks

● political sensitivity

Balance

In order to ensure the overall achievement of organisational goals, the resources should be

distributed accordingly. Two important factors for this are budget (available versus required) and capacity (available versus required expertise) (Gutiérrez & Magnusson, 2014), (Meskendahl, 2010), (de Reyck, Grushka-Cockayne, Lockett, Calderini, Moura, & Sloper, 2005), (Archer & Ghasemzadeh, 1999).

Plan

Planning prioritized projects in a timeline will enable an organisation to forecast budget and capacity needs (Biedenbach & Müller, 2012), (Platje, Seidel, & Wadman, 1994), (de Reyck, Grushka-Cockayne, Lockett, Calderini, Moura, & Sloper, 2005).

Deliver

Runtime delay, unforeseen incidents, budget violations or other risks can require senior

management to put projects on hold or even kill them. Furthermore projects will be removed from the project portfolio when they have been successfully completed (Koppenjan, Veeneman, van der Voort, ten Heuvelhof, & Leijten, 2011), (Jonas, 2010), (de Reyck, Grushka-Cockayne, Lockett, Calderini, Moura, & Sloper, 2005), (Unger, Kock, Gemünden, & Jonas, 2012).

Process distribution

There can be only one project leader for each project. Portfolio management has to be located in middle management. Prioritization has to take place at one centralized location at senior

management level in the organization (Unger, Kock, Gemünden, & Jonas, 2012) in order to prevent bureaucratic consultation structures and noise in the application (scoring) of prioritization criteria. Project planning (allocation of capacity) is a middle management task (Beringer, Jonas, & Kock, 2013), (Jonas, 2010), (Rogers & Blenko, 2006).

STAKEHOLDER ANALYSIS

Project portfolio definitions as well as the motivation for implementing PPM differ throughout the organisation. An important distinction can be observed between the list of projects that is

composed as a means for increasing transparency and overview, and the overview of running projects and their priority in terms of business goal and added value realisation.

“The collection of IT projects that are coordinated from one hand. The sum of projects.” [Directeur Business]

“Instrument to get overview over running projects and a means for keeping track of possible project delays.” [I-domein Manager]

“Provides overview of projects and their status, and should display why we do those particular projects.” [Hoofd MI]

Where the first pair of definitions suggest a need for transparency and overview, the second pair additionally suggests the need for “more strict steering” [Directeur BV] and the need for project prioritization in terms of business goals and economic value. Moreover, the need for project prioritization is not underlined by all stakeholders:

“The order of projects based on importance is irrelevant in the organisation at this moment, because we are able to run every project for which the need has been established within the budget available. Only when bottlenecks appear, choices will have to be made as to which projects to run next. That choice will then of course be based on the importance of each project.” [I-domein Manager].

“We can concern ourselves with prioritizing projects, but in the end, all of the projects have to be executed anyway.” [Directeur Business].

The specification of a business case for projects is complex, because units have to negotiate the amount of budget and capacity each unit will have to provide to the project.

“Budget is allocated to units instead of project categories. Large posts on the balance sheet contain high amounts of money, where smaller specified posts would very much increase the transparency of budget spendings.” [P&C Employee]

Clarifying the business demand by means of interplay between IT- and business units is frustrated by the knowledge and language gap between the units.

“The department is very dynamic. That makes things difficult, especially for IT units, because we are doomed to lack behind. That is why we try to communicate frequently with business managers.” [Hoofd MI]

“I am exploring what I can and cannot expect from the IT units in the department. IT units tell us that they can build things for us as long as we have a clear “question”. My managers however, do not have sufficient IT knowledge to see what possibilities exist and are not able to specify their needs in the IT detail required by the IT units. IT units on the other hand do not have sufficient knowledge of the business processes to pro-actively propose IT solutions. We have appointed a demand manager at the business units, and we try to communicate with IT unit employees that have some knowledge about the business processes, or at least the willingness to gain this knowledge.” [Directeur Business]

“IT units, IBS in particular, should know better what my wishes are and how to translate those wishes in IT solutions. IBS project leaders are sometimes very reserved, because, in my opinion, they do not have the required knowledge about IT and about my business processes.

Furthermore, it is not always clear what responsibilities each involved party should have.”

[Hoofd Business]

Political influence is viewed as a “necessary evil”, but interferes with the agenda of the department. It undermines the prioritization process because the planning of capacity and budget allocation is sometimes disturbed by incidental initiatives of politicians.

“The interaction with councillors is usually problem-based. When citizens complain, the councillor comes asking for structural reports on the situation and demands a solution.”

[Directeur BV].

“One councillor’s opinion was that we had to transform every municipal employee’s email address to a uniform format. Although the CIO staff advised him to allocate resources to - in our view - more important projects, the counselor did not. If he thinks it is sound to do something, other projects will have to make way.” [CIO Staff].

“Councillors’ influence on our agenda is most tangible during college negotiations. We need to be selective sometimes in allowing incidental initiatives and course changes, because

otherwise we would not be able to do our job properly. A portfolio could help to give councillors insight in the consequences of their choices.” [Directeur Business].

SOCIAL DYNAMICS

The culture of the organization can be described as informal and conservative. This has become very tangible recently because of developments in national politics. A lot of social services that used to be governed on a national level, now become the responsibility of the municipalities. This means a lot of changes in the organization are required simultaneously. It took employees some time to change their attitude towards these changes into a positive and open attitude. The informality of the organization is noticeable when looking at the decision making process. It is not clear who is and should be involved in a decision making process, and what role each person has and should have (Rogers & Blenko, 2006).

“Money is not an issue” used to be the motto of the organization. The meaning of the motto is that sufficient means are available to execute all projects that are deemed necessary. Optimization of budget spendings has thus not been among the goals of the organization in recent years. While senior management relies on the Iron Triangle (Cost, Time, Quality), research (Marques, Gourc, & Lauras, 2010) suggests this is inefficient in some cases. Senior management will need to start demanding such information from project owners in order to gain project and portfolio control. The I-domein manager and hoofd IBS have a clear difference in vision. This causes frustration in the collaboration between the two. Moreover, the directeur BV seems to have a better relation with the I-domein manager than with the hoofd IBS. Collaboration between the units IBS and IBO is stiff due to events in the past. ‘There is a ‘history’ between the two. These social dynamics suggest that optimal collaboration is not present within the case study organization. For privacy reasons, an elaborate diagram display of the internal relations cannot be included in this thesis publication.

“plan” and “deliver”. This was done because of the time constraint and because the elements are strongly related. The process distribution among the organisation was discussed along with each element because it was anticipated that this was virtually impossible to separate from the

discussion about the process itself.

STRUCTURING BUSINESS DEMAND

The issues that were raised on this elements were all related to the client or “commissioning party”. The commissioning party legitimacy is often uncertain and commissioning parties do not perform well. Legitimacy is uncertain because it is uncertain if the commissioning party has authorization to commission, and because business cases are often incomplete or vague.

BALANCE/CATEGORISING

Alignment of projects with the vision and strategy of the department does not take place. Senior management should show more leadership regarding the realisation of their formulated vision. No “official” widely accepted categories exist. Alignment of projects with the IT architecture does not take place. 6 8 10

Balance/Categorize

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 lack of demand overviewdemand unclear to much bottom-up formulation

bad/unclear business ownership/clientship

no demand selection separate exploration from exploitation

Structuring Demand

response

PRIORITIZING

Alignment of projects with the goals and objectives of the department does not take place. The IBS portfolio is not a department wide “complete” portfolio of projects. This makes for an incomplete view. IBS lacks sufficient knowledge of the business in which commissioning parties (clients) work. The department lacks (explicit) criteria by which the importance of projects should be determined. The practice of politics undermines the PPM process as a whole.

CONTROL

There is no clear formal role to which portfolio control is assigned. IBS should be more proactive in providing the means necessary for strategic portfolio decisions. Senior management on the other hand does not know what (kind of) information it requires to make these strategic portfolio decisions, which makes the information demand unclear for IBS. Project management is of insufficient quality to be able to make clear cut Go-No Go decisions. If the organisation does not suffer any (severe) consequences, no incentive exists to be in control of the project portfolio. The organisation is very reactive.

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

lack of business knowledge insufficient business cases lack of leadership in multiple levels

unclear criteria and scoring theirof political influence/competition undermines process

Prioritize

response 0 2 4 6 8 10IBS should deliver strategic decision

no comitment, no resources, no PMO,

no clear(formalized) decision making

lack of governance maturity level of organisation varies

no focus on result

Control

response

PLOTTING OBSERVATIONS ON THE PPM FRAMEWORK

In table 5 the results of the workshop and the analysis of the interviews are plotted onto the framework for PPM in order to gain insight in any discrepancies. Motivations of stakeholders for the implementation of PPM for example include Prioritization, Planning and Delivering. These are elements of PPM which they find very important. Although stakeholders are motivated to

implement PPM in order to improve their Project Prioritization, Planning and Delivering processes, the Understanding, Categorizing and Balancing elements are not mentioned. The workshop results suggest however, that many improvements are required in these elements as well.

Framework Workshop Stakeholders’ view

Understand

● what is current business demand? ● business case?

● forecasting

● unclear demand

● lack of demand overview ● unclear business ownership

● we do not know IT language ● IT advisors lack business process

knowledge

Categorize

● projects aligned with business strategy?

● what goal does a project achieve?

● no clear definition of categories ● business owners should decide ● need more relation management

● vision not concrete enough yet

Prioritize

● anticipated realisation of vision and strategy

● cost saving (long term)

● anticipated customer satisfaction ● compliancy (urgence)

● risks

● political influence

● lack of business knowledge ● incomplete business cases ● unclear criteria

● unclear scoring model ● political influence undermines

objectivity

● political influence makes planning difficult

● no criteria yet

● vision is not concrete enough yet ● a motivation to implement PPM ● we have to do all the projects

anyway

Balance

● resource distribution according to organisation’s goals

● no clear categories, so balancing

impossible ● budget should go to projects instead of units

Plan

● plan projects in timeline based on their priority

● forecast resource needs

● not enough governance

● no PMO, not enough commitment ● ● a motivation to implement PPM too busy solving problems at the moment

Deliver

● risk management ● GO/no-GO decisions

● no focus on results ● no clear go/no go’s

● we should document progress better

CONCLUSION

In this thesis, a municipality is used as a case study for discovering the dominant mechanisms in project portfolio implementation in practice. From the stakeholder analysis, work floor

observations and workshop, five important mechanisms can be distinguished within the organization that influence the implementation of PPM. In the case study organization, the

mechanisms do not work properly, which causes them to negatively influence PPM implementation. Different motivations for implementing a PPM can exist throughout an organisation without

problems. However, there is a risk that these different motivations go hand in hand with different visions on PPM. The view that project prioritization is required, is not widely accepted in the case study organisation. Observations suggest the slightly conservative culture in the organisation is a cause. Furthermore, the ‘money is not an issue’ motto explained earlier enfeebles the need for project prioritization. Investments have to be made before initiating implementation, to align definitions and expectations about PPM. Furthermore, formal roles in the PPM process of the case study organisation have to be apportioned early in the implementation, because responsibilities of involved employees will be clear from the start.

Within any organization people will have different perspectives, motivations and opions on PPM. It can thus be argued that the definition of PPM and goal of implementing a PPM process in an

organization should be discussed elaborately in the organization before starting in order to ensure that everyone is working towards the same goal.

Perhaps the most important element of PPM is the availability of management information. Reporting structures for project leaders and structures for business case compilation are requirements for successful PPM implementation. No iterative process is established in the case study organisation in which a project status and risk analysis of all projects is delivered. This leaves project management suboptimal (Milosevic & Patanakul, 2005). Moreover, it makes the process of gathering all required information for the portfolio very time consuming. No complete and up to date portfolio can be assembled in this manner, because the information about one project will be outdated by the time information about all other projects is delivered. A PMO is required in the case study organisation to safeguard the PPM process and supply of project information (Unger,

Gemünden, & Aubry, The three roles of a project portfolio management office: Their impact on portfolio management execution and success, 2012) in order to secure PPM success. The

importance of the PMO role is not recognized by senior management in the case study organization eventhough research marks PMO creation as an organizational innovation (Hobbs, Aubry, &

Thuillier, 2008). Considering the above, it can be argued in general that no organization will be able to implement PPM without the support of a solid project information infrastructure. For this infrastructure sufficient project maturity is required (Andersen & Jessen, 2003).

A problem acknowledged by stakeholders as well as in the workshop is the gap between business experts and IT experts. In the case study organisation this is a major source of noise in the demand specification. Furthermore, no clear business owner is available in the case study organisation for finetuning the demand during the project. Project leaders should be the binding factor between business and IT experts, and should therefore have knowledge about business processes as well as

require expert knowledge in all fields, project leaders in any organization need to be able to understand their team members regardless their expertise. If project leaders fail to understand their team members, they will not be able to facilitate communication between experts of different fields in order to specify a project goal and business case. Furthermore research (Martinsuo & Lehtonen, Role of single-project management in achieving portfolio management efficiency, 2007) indicates that understanding of portfolio level issues needs to be considered as part of project leaders’ capabilities and not only a top management concern if portfolio success is to be optimized. Political influence in the municipality’s agenda is normal according to stakeholders. However, the lack of dialogue between politicians and civil servants can result in political decisions of which the consequences for civil servants are unacceptable. The governmental innovation agenda is often compromised by political incidental demands. This leaves the organisation unable to forecast projects and thus forecast resource needs. Stakeholders do believe however, that a portfolio has the potential to be the instrument that enables the organisation to provide politicians with insight in the consequences of their decisions.

Political influence is a mechanism that occurs in all organizations for any organization contains people that aim at personal gains or at satisfying shareholders or their electorate. This research shows the negative impact political influence has on the prioritization and planning of projects. Clear boundaries need to be set by an organisation regarding the degree of interference on the project agenda that should be allowed. If an organisation fails to do so, it will remain incident driven, unstable and inconsistent in its development agenda.

Stakeholders as well as workshop participants share the view that budget should be allocated to projects. Project budget is now composed of contributions of different units. This complicates project ownership, commitment from different units, and allocation of budget and resources even more than should be expected in the multi-project settings (Engwall & Jerbrant, 2003).

In general, it can be argued that a solid foundation for PPM is required in the organisation for implementation of PPM to be successful. Five mechanisms in this required foundation have been identified in the case study organisation. Insights are provided in the problems that occur in the case study organisation when such a foundation is not present.

DISCUSSION

Triangulation is used in this thesis to validate the presented results. 1) The workshop session with the employees responsible for the projects and project portfolio gives insight in the self-image of the implementers and their view on the organisation. 2) Stakeholders of the portfolio have been interviewed throughout the department to gain insight in their expectations, issues and views. 3) Participant observation in the organisation for a period of three months by means of attending meetings and observing the work floor leads to a third source of insights. Participant observation is conducted by a biased human who serves as the instrument for data collection. Gender, sexuality, ethnicity, class, and theoretical approach may affect observation, analysis, and interpretation. Although some conclusions concern subjects that have already been associated with PPM, this research has yielded new insights as well. Major mechanisms of PPM in practice are the handling of politics, minimizing its influence on the project prioritization process and the influence of budget allocation on clear project ownership. The five described elements can be viewed as a “checklist” for creating the right invironment for PPM implementation in an organization. This checklist is valuable for many organisations because it addresses practical mechanisms that occur in all kinds of organisations. The checklist can prepare an organization for the implementation of a sustainable project portfolio management process that is carried within the organisation while minimizing risks of implementation failure.

This research provides a startingpoint for further research with more case studies which is needed to validate and complement this checklist. Additionally, an interesting topic that could not be addressed in this thesis due to time constraints is the comparison of the observed mechanisms in the case study organization, with the mechanisms of an organization in which PPM implementation has been successful.

REFERENCES

Andersen, E. s., & Jessen, S. A. (2003). Project maturity in organisations. International Journal of Project Management(21), 457-461.

Archer, N. P., & Ghasemzadeh, F. (1999). An integrated framework for project portfolio selection.

International Journal of Project Management(17), 207-2016.

Beetsma, A. (2011). Portfoliomanagement, een hoofdtaak van de CIO. Sdu Uitgevers.

Beringer, C., Jonas, D., & Kock, A. (2013). Behavior of internal stakeholders in project portfolio management and its impact on success. International Journal of Project Management(31), 830-846.

Biedenbach, T., & Müller, R. (2012). Absorptive, innovative and adaptive capabilities and their impact on project and project portfolio performance. International Journal of Project Management(30), 621-635.

Cooper, R. G., Edgett, S. J., & Kleinschmidt, E. J. (1998). Best practices for managing R&D portfolios.

Research technology management(41), 20-33.

Cooper, R. G., Edgett, S. J., & Kleinschmidt, E. J. (2000). New problems, new solutions: making portfolio management more effective. Research-Technology Management(43), 18-33. de Reyck, B., Grushka-Cockayne, Y., Lockett, M., Calderini, S. R., Moura, M., & Sloper, A. (2005). The

impact of project portfolio management on information technology projects. International Journal of Project Management(23), 524-537.

Eisenhardt, K. M. (1989). Building Theories from Case Study Research. Academy for Management Review(14), 532-550.

Engwall, M., & Jerbrant, A. (2003). The resource allocation syndrome: the prime challenge of multi-project management? International Journal of Project Management(21), 403-409.

Flyvbjerg, B. (2006). Five Misunderstandings About Case-Study Research. Qualitative Inquiry(12), 219-245.

Great, B. (2008). Office of Government Commerce, & Office of Government Commerce Staff.

Gutiérrez, E., & Magnusson, M. (2014). Dealing with legitimacy: A key challenge for Project Portfolio Management decision makers. International Journal of Project Management(32), 30-39. Hobbs, B., Aubry, M., & Thuillier, D. (2008). The project management office as an organisational

Kawulich, B. B. (2005, May). Participant Observation as a Data Collection Method. Retrieved June 2014, from Forum: Qualitative Social Research:

http://www.qualitative-research.net/index.php/fqs/article/view/466/996

Koppenjan, J., Veeneman, W., van der Voort, H., ten Heuvelhof, E., & Leijten, M. (2011). Competing management approaches in large engineering projects: The Dutch RandstadRail project.

International Journal of Project Management, 740-750.

Marques, G., Gourc, D., & Lauras, M. (2010). Multi-criteria performance analysis for decision making in project management. International Journal of Project Management(29), 1057-1069. Martinsuo, M. (2013). Project portfolio management in practice and in context. International

Journal of Project Management(31), 794-803.

Martinsuo, M., & Lehtonen, P. (2007). Role of single-project management in achieving portfolio management efficiency. International Journal of Project Management(25), 56-65.

Meskendahl, S. (2010). The influence of business strategy on project portfolio management and its success - A conceptual framework. International Journal of Project Management(28), 807-817.

Milosevic, D., & Patanakul, P. (2005). Standardized project management may increase development projects success. International Journal of Project Management(23), 181-192.

Pendharkar, P. C. (2014). A decision-making framework for justifying a portfolio of IT projects.

International Journal of Project Management(32), 625-639.

Platje, A., Seidel, H., & Wadman, S. (1994). Project and portfolio planning cycle, Project-based management for the multiproject challenge. International Journal of Project

Management(12), 100-106.

Rogers, P., & Blenko, M. (2006). Who Has the D? - How Clear Decision Roles Enhance Organizational Performance. Harvard Business Review.

Schreinemakers, J. F., & van Engers, T. M. (2007). 15 Years of Knowledge Management (Vol. 3). Unger, B. N., Gemünden, H. G., & Aubry, M. (2012). The three roles of a project portfolio

management office: Their impact on portfolio management execution and success.

International Journal of Project Management(30), 608-620.

Unger, B. N., Kock, A., Gemünden, H. G., & Jonas, D. (2012). Enforcing strategic fit of project

portfolios by project termination: An empirical study of senior management involvement.

International Journal of Project Management(30), 675-685.

van Enk, J. H., Everaert, A., Lammertink, M., Notenboom, K., & Pattynama, J. (2014). Program and Project Portfolio Dashboards and their applicability to the Dutch Police Organization.

APPENDIX A: INTERVIEW QUESTIONS

NOTE: not all questions have been posed toe ach interviewee. Depending on their role and

expertise in the organisation, a selection of relevant questions was made from the questions below.

What exactly is your role in the organisation?

What is a project portfolio?

What is your interest in the project portfolio that is currently developed at IBS?

Why do you need to make choices between projects? What bottlenecks force you to choose?

What makes a project important?

Are you happy as a business client of IBS?

Are you in control?

Are many projects going over budget?