ABSTRACT.Duringthefirstyearoflifea groupofbabies was prospectively observed for diarrhea and for fecal carriage of heat-labile toxigenic bacteria, with or without colonization factor, and rotavirus. Approximately half of the babies were breast-fed for the first six months of life. There was no difference between groups (breast-fed vs non-breast-fed) in number of babies who had diarrhea during any two-month period. Nor was there any differ ence between groups in the number of babies who had diarrheawhile carrying toxigenicbacteria,with or with out colonization factor. Secretory antibody to toxin was found in 37%of colostrum and milk samples. There was a small but insignificant difference in the number of babies who had diarrhea when they carried toxigemc bacteria depending on the presence of antibody in the breast milk they received. Pediatrics 70:921—925,1982; diarrhea, breast-fed infants, non-breast-fed infants.

It is widely believed that breast-fed (BF) babies have diarrhea less than non-breast-fed (NBF) ba bies. Clinical studies of diarrhea in BF and NBF infants, however, have not uniformly supported that belief.'5 Specific and nonspecific anti-infective factors have been demonstrated in human breast milk in vitro6'7 but efficacy of the individual factors has not been demonstrated in vivo.

We prospectively observed babies in the first year of life to study the relationship between exposure to diarrhea etiologic agents and development of diarrhea. We measured secretory immunoglobulin A (SIgA) antibodies to the agents in colostrum and breast milk. The following is a report of the obser vations.

Received for publication Jan 18, 1982; accepted March 18, 1982. Reprint requests to (A.H.C.) Department of Pediatrics, Univer sity of New Mexico, School of Medicine, Albuquerque, NM 87131.

PEDIATRICS (ISSN 0031 4005). Copyright ©1982 by the American Academy of Pediatrics.

POPULATION AND STUDY METHODS

Forty women who received prenatal care at the University of New Mexico Hospital and who were late in pregnancy were enrolled between February and December 1979. There was an equal number of enrollees (ten) in each three-month period. BF and NBF infants (5:5) were equal in the first two en roilment periods. There were more BF infants (9:1) in the third period and more NBF infants (8:2) in the fourth period. The only requirement for enroll ment was willingness to participate in a long-term study.

One of us (L.A.) collected cord blood and feces from the baby, and blood, feces, and colostrum from the mother within three days of delivery. The same person then visited each baby's home weekly to administer a questionnaire and to collect a fecal sample from the baby. Each baby was weighed and measured monthly and a breast milk sample was collected once every three months aslong as breast feeding continued. Mothers were asked to report by telephone if a baby had diarrhea between routine visits. The nurse then visited the home to verify the diagnosis and to collect an additional fecal sample. Questions about the baby's feeding, symptoms of ifiness, medical visits, and medications were asked weekly. Age, years of formal education, ethnicity, career (housewife or other) of mother, number of siblings, ownership and water supply of the home, day care exposure of the baby, and medical care source were asked once and revised if changes oc curred.

Fecal samples were cultured on eosin methylene blue agar and ten to 20 colonies were identified8 and tested for production of heat-labile toxin (LT) by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).9 Antisera to purified cholera toxin were used in the assay. Toxins of Clostridium difficile, Clostridium perfringens (type C, /3-toxin), and Aeromonas hydrophila did not cross-react in the

Diarrhea

inBreast=Fed

and Non-Breast-Fed

Infants

Alice H. Cushing, MD, and Linda Anderson, RN

TABLE1 .BabyNo. Diarrhea Episodes per ofEpisodesNon-Breast-Fed1492510301422Breast-Fed

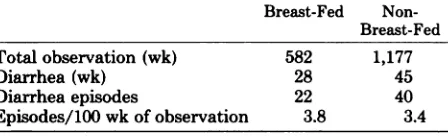

Total observation (wk)5821,177Diarrhea (wk)2845Diarrhea

episodes2240Episodes/100

wk of observation3.83.4 test. Fecal suspensions were assayed for rotavirus

by ELISA.'° Specimens were tested as soon as they were collected or were stored at —¿70C for up to six months before testing. Positive and negative con trols were stored with each batch of specimens to ascertain that storage conditions were satisfactory. To determine whether colonization factor antigen (CFA) was present, LT-positive colonies were tested for agglutination of human type A, bovine, guinea pig, and chicken red blood cells in the pres ence of mannose.―

Colostrum and breast milk were centrifuged and the nonfat supernatant fluid was stored at —¿70C until all specimensfrom a single individual could be tested at the same time, a period of three to 12 months. Samples (at 1:8 dilution) were assayed for secretory IgA antibody to LT and to rotavirus (SA 11 virus was substituted for human rotavirus) by ELISA.'2

Definitions

Diarrhea was defined as passage of 3 unformed stools per day by NBF babies. BF babies, who may normally pass feces with increased water content,'3 were considered to have diarrhea only if they had 2 stools per day more than they normally had (as determined by prediarrhea observation) and all stools were unformed. A diarrhea week was defined as a week with 2 days of diarrhea; a diarrhea episode was defined as 2 days of diarrhea not separated by 2 diarrhea-free days. An episode of diarrhea was defined as toxin-related if LT-positive bacteria were detected within one week of the epi sode. Day care exposure was exposure to 4 chil then less than 4 years of age 3 days/wk for 4 hr/ day. A baby was considered to be BF if he or she was breast-fed 2/day, regardless of other food intake. For purposes of analysis, a baby was cate gorized as BF only if he/she was breast-fed for one of the two months of the analysis period. No BF baby had diarrhea during the portion of an analysis period that he was NBF.

If the baby's weight decreased from the usual curve to a lower one on a standard growth chart'4 (eg, 25th to tenth), because of weight loss or failure to gain, within one to four weeks after an episode, the episode was said to have caused weight curve effect (WCE).

Statistical Methods

By two-month periods, babies who had diarrhea were compared with the total number ofbabies who were fed by that method. Days, weeks, and episodes ofdiarrhea in each group were compared by Fisher's exact test. Duration of diarrhea data was analyzed

by x2. Differences that were not statistically signif icant (P > .05) were designated NS.

RESULTS

Study Groups

BF and NBF groups were comparable for sex, career of mother, number of siblings, water source, medical care source, and day care. Breast-feeding mothers had more formal education, and more fam ilies of breast-fed infants owned their homes. Non breast-feeding mothers were significantly younger and more of them were Hispanic. All babies were born at term and grew normally except as described. Breast-feeding was never stopped because of diar rhea. No family was removed from the study for failure to cooperate. Families left the study for various reasons, most by moving away from Albu querque.

Overall Occurrence of Diarrhea

Thirty of the 40 babies had 62 episodes of diar rhea during 312 days in 73 weeks (Tables 1 and 2). Two BF infants and three NBF infants had more than two episodes. Nine babies (four BF, five NBF) did not have diarrhea. There was no significant difference in the overall occurrence of diarrhea when the groups were compared by episodes per baby (Table 1) or by total weeks of observation (Table 2). No baby had diarrhea in the first month. Diarrhea episodesby two-month periods are shown in Table 3. It is also shown in Table 3 that some BF babies became NBF. Three BF babies had diarrhea

after they had stoppedbreast-feedingwhile eight

did not.BF babies who were introduced to solid foods within the first three months of life had no more diarrhea episodes than BF babies who received no solid foods. This was true whether they were com

TABLE 2 Weeks of Observation/Weeks of Diarrhea Breast-Fed Non

TABLE 3. BabieswithDiarrheabyAgeGroupandby Mode of Feedingat Onsetof Diarrhea

Age(mo)Breast-FedNon-Breast-Fed1—22/201/203—44/178/21(2)*5—64/154/21(2)7—S4/113/25(4)9—106/76/29(3)*

TABLE4.EpisodesEpisodeDurationof Diarrhea DurationBreast-Fed

Non-Breast-Fed(days)2—49265—71010>734Total2240

TABLE 5. Weeks richia coli Comparedof

Carriage of LT+/CFA+ Esche with Weeks of

DiarrheaWeeks

withBreast-Fed Non-Breast-FedLT+

E coli Diarrhea

LT+/CFA+ E coli Diarrhea49

54

6 (12%) 7 (13%)

13 9

2 (15%) 2 (22%)

pital during the same period as that encompassed by this study. In previous studies serum antibodies to LT were found in 28% and antibodies to rotavirus were found in 43% of children 1 to 2 years of age on admission to UNM Hospital for all causes.

Milk Antibodyto LT

Ten of 27 colostrum samples had LT-SIgA as did 3/16 milk samples at 3 months of age, 1/11 at 6 months of age, and 0/5 at 9 months of age. Of 17 babies who carried toxigenic organisms, seven re ceived breast milk with LT-SIgA and one had diar rhea. Ten of the 17 received milk that did not have antibody and five of them had diarrhea while they carried toxigenic organisms (NS).

DISCUSSION

There is some question whether breast milk spe cifically protects babies against diarrhea. Breast feeding may be associated with less diarrhea in underdeveloped countries only becauseit is cleaner than non-breast-feeding. The ideal study to answer the question would be a prospective one in which adequate numbers of comparable babies would be randomly assigned to groups in which they would be fed exclusively by that method for the duration of the study. Babies in both groups would be ob served equally for exposure to diarrhea etiologic agents as well as for duration and severity of diar rhea episodes.All terms would be clearly definedin advance.

The obstacles to performing such a study are evident. A range of compromises with the ideal is exhibited by the relevant literature. Nearest the ideal is the Norrbotten stud? in which 400 Swedish

* Values in parentheses indicate babies who were breast

fed during previous two months.

pared by month or cumulatively. By the end of the fourth month of life all BF babies had had solid foods.

Duration of Diarrhea

There was no difference between groups in the duration of individual diarrhea episodes (Table 4).

Seasonal Occurrence of Diarrhea

Breast-fed babies had significantly more diarrhea episodes in January through March whereas NBF

infants had more diarrhea in April through June.

This may reflect, in part, the unequal enrollment. Eight BF babies were born in September through October, and in January through March they were 3 to 6 months of age, ages at which eight (40%) of 22 BF episodes occurred. Seven NBF infants were born in December and January, and were 3 to 6 months old between April and June. These were months in which 15 (40%) of 40 diarrhea episodes occurred in NBF infants. Toxigenic bacteria were isolated most often in June and July.Severity of Diarrhea

No baby was hospitalized for diarrhea. Eight BF babies were taken to the doctor for 14 of the 22 episodes experienced by the group. Ten NBF babies were taken to the doctor for 12 of the 40 episodes in that group (NS). Seven BF babies had WCE follow ing eight of the 22 BF episodes whereas six NBF

infants had WCE following 11of 40episodes(NS).

Exposure to Toxigenic Bacteria

Exposures to LT-positive and to LT-positive/ CFA-positive bacteria, equated here with fecal car riage, were similar, as shown in Table 5, for both groups aswas diarrhea in association with exposure. In no case was another bacterial pathogen or rota virus detected during an LT-positive week. Al though the community prevalence of these two agents has not been fully investigated, LT-positive bacteria were isolated from 24% and rotavirus was identified in feces of 40% of children admitted for diarrhea to University of New Mexico (UNM) Hos

* Abbreviations used are: LT+, heat labile toxin-positive;

babies were prospectively observed monthly during the first year of life for feeding methods and for a number of ifinesses. There was no significant differ ence between feeding groups in the number of ba bies who had diarrhea. Duration and severity of diarrhea were not assessed.A group of British doc tors5 observed 334 babies monthly during the first year and found no difference in the number of gastrointestinal ifinesses between BF babies and NBF babies. Workers in New Zealand,'5 however, found, in a prospective study of 1,156 infants, that gastrointestinal illnesses decreased with increasing duration of breast-feeding up to four months. Data were compiled from diaries, medical visits, and re call.

Differences in methodology make studies of diar rhea in breast-fed and artificially fed babies in the United States difficult to compare.'6 Most studies have been retrospective.'72' Important data may not have been available, and subjects in both groups may not have been observed equally.

Some studies have compared hospitalized babies with babies similarly fed in the community and have concluded that breast-feeding prevents ill ness.22'@Those studies may be criticized for the methods of estimating feeding groups in the com munity and for inferring comparability of popula tions that cannot be assumed from the methods employed. Breast-feeding has been defined var iously as strictly BF,2―822fed any amount per day for three months,'9, or 4½months.@°2'Diarrhea was not defined in any of the studies.

It is difficult to gather data on duration of breast feeding, amount per day, and supplementation.'6 These items are frequently lacking in retrospective studies. Handling of data, once gathered, may be another source of variabifity among studies. For example, Cunningham'@°'2'assigned babies to a feed ing category on the basis of duration of breast feeding and compared ifinesses in those groups even after they ceased breast-feeding. We reassigned ba bies to the NBF group within one month after breast-feeding ceased (Table 3) and attributed no ifinesses to a BF baby unless the baby was actually breast-feeding at the time the illness began. Such methodologic procedures conceivably affect out come, thus conclusions, to a significant degree.

In this prospective study we were unable to dem onstrate a difference in numbers, duration, or Se verity of diarrhea episodes experienced by BF in fants as compared with NBF babies even during the first two months of life when breast milk con stituted the major portion of dietary intake. Thus, we concluded that breast milk did not nonspecifi cally prevent diarrhea.

To examine the specific effects of breast-feeding

on response to exposure, we compared diarrhea episodes in the two groups of babies with carriage of rotavirus and toxigenic Escherichia coli. Rota virus was found too infrequently in the first six months to permit meaningful analysis. However, LT, the heat-labile enterotoxin of E coli, which is immunologically cross-reactive with cholera toxin and which causes diarrhea by the same mecha nism24 was found repeatedly and with equal fre quency in both groups. With exposure, similar per centages of BF babies and NBF babies had diar rhea.

The reason that diarrhea was so infrequent with carriage of LT-positive organisms is unknown. The sensitivity of the assay (6 pg of cholera toxin) was similar to that of the Y-1 cell assay,@ the standard test for LT production. Biologic activity of the toxin identified by ELISA was verified by Y-1 cell assay of randomly selected isolates. Satterwhite et al26 showed that LT-positive E coli were more likely to cause diarrhea if they had a surface component (CFA) than if they did not. Here LT-positive/CFA positive E coli were found with equal frequency in BF babies and NBF babies. Babies in both groups had diarrhea during a small but equal percentage of weeks in which they carried the organisms.

It was then hypothesized that protection could be demonstrated only if breast milk had antibody against the specific agent to which the baby was exposed. Babies who carried LT-positive bacteria and whose breast milk had antibody to toxin had diarrhea less often than babies with LT-positive bacteria whose breast milk did not have antibody. Differences, however, were not significant in the small number of babies in whom this comparison could be made.

Biases in this study, which would have been expected to favor the BF group, include the higher educational and economic (evidenced by home own ership) levels of the BF group. Also, there were more episodes of diarrhea late in the babies' first year of life as increasing numbers of babies were NBF. The effect of linkage of variables such as ethnicity with educational and socioeconomic levels is unknown as are those of nonrandom enrollment of subjects and seasonal differences in diarrhea in BF and NBF groups.

The measures of severity may be criticized. Doc tor visits reflected parental concern and accessibil ity of medical care as well as actual severity of disease. Although medical care was, theoretically, available at all times to all babies, other socioeco nomic factors, such as availability of transportation, may have prevented actual access.

The use of WCE to measure severity may have

caloric restriction. This was known to be the case in only one baby in each group. That relatively mild diarrhea affected the weight gain of 13 babies to the extent it did was unexpected. This has been re ported from underdeveloped countries27where pre cariously nourished babies became overtly mal nourished following an episode of diarrhea. Albu querque babies in both groups resumed their former growth curves within two months after the episode.

In this small group of prospectively observed, adequately nourished babies, breast-feeding did not result in fewer, briefer, or less severe diarrhea epi sodes in the recipients than in a group of partially comparable NBF babies. There was no difference between groups with respect to diarrhea following exposure to LT. A significant protective effect of breast milk antibody to LT could not be demon strated with the number of babies studied.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grant AI-13785 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

We thank Joanne Smart, BSMT, for supervision of

performanceof laboratoryprocedures;Betty E. Skipper, PhD, for statistical analysis;SophieGarvanian,for man uscript preparation; and Dr Lawrence Berger and Dr Alfred Florman for review of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

1. Stanfield P: Breast feeding and artificial feeding: A survey of the literature. Acta Paediatr Scand (Suppi 116)48:11,1959 2. Mellander 0, Vahlqvist B, Meilbin T: Breast and artificial

feeding. the Norrbotten Study. Acta Paediatr Scand (Suppi

116) 48:55, 1959

3. GlazierMM: Comparingthe breast-fedand the bottle-fed infant. N Engi JMed 203:626, 1930

4. Stevenson SS: The adequacy of artificial feeding in infancy.

JPediatr3l:616, 1947

5. The Research Sub-committee, South-East England Faculty, Royal College of General Practitioners: The influence of breast feeding on the incidence of infectious illness during the first year of life. Practitioner 209:356, 1972

6. Welsh JK, May JT: Anti-infective properties of breast milk.

J Pediatr 94:1, 1979

7. Goldman AS, Smith CW: Host resistance factors in human

milk. J Pediatr 82:1082,1973

8. Edwards PR, Ewing WH: Identification of Enterobacteria ceae, ed 3. Minneapolis, Burgess Publishing Co, 1972 9. Yolken RH, Greenberg HB, Merson MH, et al: Enzyme

linked immunosorbent assay for detection of Escherichia coli heat-labile enterotoxin. J Clin Microbiol 6:439, 1977

10. Yolken RH, Kim NW, Clem T, et al: Enzyme-linked immu nosorbent assay (ELISA) for detection of human reovirus like agent of infantile gastroenteritis. Lancet 2:263, 1977 11. Evans DJ, Evans DE, DuPont HL: Hemagglutination pat

tenis of enterotoxigenic and enteropathogenic Escherichia coli determined with human, bovine, chicken and guinea pig erythrocytes in the presence and absence of mannose. Infect Immun 23:336, 1979

12. Simhon MI, Yolken RH, Mata L: S-IgA cholera toxin and rotavirus antibody in human colostrum. Acta Paediatr Scand68:161, 1979

13. Bullen CL, Willis WT: Resistance of the breast-fed infant to gastroenteritis. Br Med J 3:338, 1971

14. Reed RB, Stewart HC: Patterns of growth in height and weight from birth to eighteen years ofage. Pediatrics 24:904, 1959

15. Fergusson DM, Horward U, Shannon VT', et al: Breast feeding, gastrointestinal and lower respiratory illness in the first two years. Aust Paediatr J 17:191, 1981

16. Sauls HS: Potential effect of demographic and other vari ables in studies comparing morbidity of breast-fed and bot tle-fed infants. Pediatrics 64:523, 1979

17. Woodbury RM: The relation between breast and artificial

feeding and infant mortality. Am J Hyg 2:668, 1922 18. GruleeCG, SanfordHN, Herron PH: Breast and artificial

feeding: Influence on morbidity and mortality of twenty thousand infants. JAMA 103:735,1934

19. Adebonojo FO: Artificial vs breast feeding: Relation to infant health in a middle class American community. Clin Pediatr 11:25, 1972

20. Cunningham AS: Morbidity in breast fed and artificially fed infants. J Pediatr 90:726, 1977

21. Cunningham AS: Morbidity in breast fed and artificially fed infants. II. J Pediatr 95:685, 1979

22. Fallot ME, Boyd JL HI, Oski FA: Breast-feeding reduces incidence of hospital admissions for infections in infants. Pediatrics 65:1121, 1980

23. Larsen SA, Homer DR: Relation of breast versus bottle feeding to hospitalization for gastroenteritis in a middle-class U.S. population. J Pediatr 92:417, 1978

24. Sack RB: Human diarrheal disease caused by enterotoxi

genic Escherichia coiL Annu Rev Microbiol 29:333, 1975

25. Donta ST, Moon HW, Whipp SC: Detection of heat-labile

Escherichia coli enterotoxin with the use of adrenal cells in

tissue culture. Science 183:334, 1974

26. Satterwhite TK, Evans DG, Dupont HL, et al: Role of

Escherichia coli colonization factor antigen in acute diar

rhea. Lancet 2:181,1978

1982;70;921

Pediatrics

Alice H. Cushing and Linda Anderson

Diarrhea in Breast-Fed and Non-Breast-Fed Infants

Services

Updated Information &

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/70/6/921

including high resolution figures, can be found at:

Permissions & Licensing

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/Permissions.xhtml

entirety can be found online at:

Information about reproducing this article in parts (figures, tables) or in its

Reprints

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/reprints.xhtml

1982;70;921

Pediatrics

Alice H. Cushing and Linda Anderson

Diarrhea in Breast-Fed and Non-Breast-Fed Infants

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/70/6/921

the World Wide Web at:

The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is located on

American Academy of Pediatrics. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 1073-0397.