INTRODUCTION

The ErbB receptor family comprises four members, designated epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR or ErbB-1), ErbB-2 (HER2 or neu), ErbB-3 and ErbB-4 (1–3). In the adult, all four recep-tors are widely expressed at low levels. However, overexpression of ErbB1 and/or ErbB2 was implicated in the pathogenesis of many carcinomas, in-cluding those derived from head and

neck (4,5), breast (6,7), lung (8), gastro -intestinal tract (4,9), prostate (10,11), gy-necologic tract (12,13) and pancreas (14). Aberrant ErbB signaling promotes resist-ance to commonly used therapeutic modalities, including hormonal agents (15), chemotherapy (16) and radiother-apy (17). On the basis of the oncogene addiction concept, it is therefore logical that individual ErbB receptors have been targeted in patients with cancer.

How-ever, results have often failed to meet a prioriexpectations.

Rather than signaling in isolation, it is increasingly appreciated that ErbB recep-tors operate as a closely integrated spec-trum of dimers (1–3). The synergistic and interdependent nature of the network is illustrated by the markedly greater trans-forming capacity of ErbB heterodimers than homodimers (18). Although all pos-sible dimers have been detected, pairing is hierarchical (18). The ErbB2 orphan receptor lacks a high affinity ligand. None -theless, it is the preferred partner for other ErbB receptors and delivers potent tyrosine kinase-driven signaling, particu-larly when paired with ErbB1 or ErbB3 (7). Increasing evidence also supports the key importance of ErbB3 in transforma-tion, a role that has been underestimated by the oncogene addiction paradigm (5,7,11,13,14). Although ErbB3 has a

con-Using Genetically Engineered T Cells

David M Davies,

1Julie Foster,

2Sjoukje J C van der Stegen,

1Ana C Parente-Pereira,

1Laura Chiapero-Stanke,

1George J Delinassios,

1Sophie E Burbridge,

1Vincent Kao,

1Zhe Liu,

1Leticia Bosshard-Carter,

1May C I van Schalkwyk,

1Carol Box,

3Suzanne A Eccles,

3Stephen J Mather,

2Scott Wilkie,

1and

John Maher

1,4,51King’s College London, King’s Health Partners Integrated Cancer Center, Department of Research Oncology, Guy’s Hospital Campus,

London, UK; 2Centre for Molecular Oncology and Imaging, Barts Cancer Institute, Queen Mary University of London, London, UK; 3Tumour Biology and Metastasis, Cancer Research UK Cancer Therapeutics Unit, The Institute of Cancer Research, Sutton, Surrey, UK; 4

Department of Immunology, Barnet and Chase Farm National Health Service (NHS) Trust, Barnet, Hertfordshire, UK; and 5Department of Clinical Immunology and Allergy, King’s College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, Denmark Hill, London, UK

Pharmacological targeting of individual ErbB receptors elicits antitumor activity, but is frequently compromised by resistance leading to therapeutic failure. Here, we describe an immunotherapeutic approach that exploits prevalent and fundamental mechanisms by which aberrant upregulation of the ErbB network drives tumorigenesis. A chimeric antigen receptor named T1E28z was engineered, in which the promiscuous ErbB ligand, T1E, is fused to a CD28 + CD3ζendodomain. Using a panel of ErbB-engineered 32D hematopoietic cells, we found that human T1E28z+T cells are selectively activated by all ErbB1-based

homod-imers and heterodhomod-imers and by the potently mitogenic ErbB2/3 heterodimer. Owing to this flexible targeting capability, recogni-tion and destrucrecogni-tion of several tumor cell lines was achieved by T1E28z+T cells in vitro, comprising a wide diversity of ErbB receptor

profiles and tumor origins. Furthermore, compelling antitumor activity was observed in mice bearing established xenografts, char-acterized either by ErbB1/2 or ErbB2/3 overexpression and representative of insidious or rapidly progressive tumor types. Together, these findings support the clinical development of a broadly applicable immunotherapeutic approach in which the propensity of solid tumors to dysregulate the extended ErbB network is targeted for therapeutic gain.

Online address: http://www.molmed.org doi: 10.2119/molmed.2011.00493

Address correspondence toJohn Maher, King’s College London, King’s Health Partners In-tegrated Cancer Center, Department of Research Oncology, Guy’s Hospital Campus, Great Maze Pond, London SE1 9RT, UK. Phone: +44-2071881468; Fax: +44-2071880919; E-mail: john.maher@kcl.ac.uk.

siderably diminished kinase activity, it is the primary hub by which the network recruits phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase signaling. In some models, ErbB3 is an obligate partner in tumorigenesis driven by ErbB1 and ErbB2 (19). In contrast to ErbB1-3, however, the role of ErbB4 in oncogenesis remains much less clear.

Pharmaceuticals directed individually against ErbB1 or ErbB2 have attracted con-siderable interest in the treatment of many cancer types. Inevitably, however, tumor cells acquire resistance to the selective pressure imposed by these agents. Often, this results from enhanced signaling by nontargeted ErbB receptor dimers (20–26). Recognition of this fact, coupled with the realization that the ErbB network is both integrated and dynamic, has resulted in the development of therapies directed against two or more family members (27–29). Even still, durable success may be difficult to attain owing to the profusion of ErbB dimers and panoply of alternative pathways that can provide necessary sig-nals to tumor cells (30–32). To circumvent this, we developed a directly cytotoxic ap-proach that couples T-cell activation with the detection of ErbB dimer overexpres-sion on the tumor cell surface.

Chimeric antigen receptors (CARs) are fusion molecules in which a targeting moiety is coupled in series to hinge, trans-membrane and activating endodomains (33,34). When expressed in T-cells, CARs engage a designated native “antigen” on the tumor cell, obviating the need for ei-ther HLA expression or antigen process-ing. Target binding is coupled with deliv-ery of a tailored activating signal, leading to tumor cell destruction and incitement of secondary immune amplification mechanisms. To engineer a CAR with broad specificity for the ErbB network, we have exploited a promiscuous ErbB ligand named T1E as the targeting moiety (35). T1E is a chimeric polypeptide in which the N-terminal seven amino acids from human transforming growth factor (TGF)-αhave been fused to the C-terminal 48 amino acids of epidermal growth fac-tor (EGF) (Figure 1A). Like both parent cytokines, T1E binds with high affinity to

the ErbB1-based homodimers and het-erodimers. Uniquely, however, T1E also binds ErbB2/3 heterodimers with compa-rable affinity to the natural ligand (hereg-ulins) but does not bind to ErbB2 or ErbB3 alone (35). We hypothesized that a T1E-based CAR would harness T-cell munity against “driver” ErbB dimers im-plicated in the pathogenesis of several tumor types, leading to therapeutically beneficial responses.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Constructs

The leader sequence of the human colony-stimulating factor-1 receptor was placed upstream of T1E sequences to maximize probability of signal cleavage at the precise junction with the TGF-α N-terminus (SignalP 3.0 server; Figure 1B). The cDNA was synthesized as an Nco1-Not1 cassette by overlap ex-tension polymerase chain reaction and was substituted for the scFv in SFG P28z (36) (Figure 1C).

The T1NA (T1E no activation domain) control CAR is identical, except that the endodomain has been truncated to con-tain only the membrane proximal three amino acids of CD28 (see Figure 1C). In the EGF28z construct (see Figure 1C), full-length mature EGF was placed downstream of a CD8αleader sequence (bases 1–60) to maximize the probability of signal cleavage at the junction with the EGF N-terminus (SignalP 3.0 server). The S28z CAR (37) contains an scFv derived from the SM3 hybridoma (MUC1 specific) and serves as an endodomain-matched control, since it does not bind MUC1 efficiently.

The 4αβchimeric cytokine receptor was coexpressed with CARs using an in-tervening T2A peptide, placed down-stream of a furin cleavage site (38). Fire-fly luciferase was expressed in the indicated tumor cell lines using the pBabe purovector (37). Full-length MUC1 was expressed using the SFG retroviral vector as described (37).

ErbB cDNAs in pcDNA3 were gifts from Professor Y. Yarden (Weizmann

In-stitute, Rehovot, Israel). Human ErbB4 cDNA was a gift from Dr. I. Hiles (Well-come Foundation). Both ErbB2 and ErbB4 were cloned into the Nco1 site of the SFG retroviral vector.

Generation/Maintenance of ErbB-Expressing 32D Cells

The ErbB-negative murine myeloid cell line 32D was maintained in RPMI 1640 + 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) + 15% WEHI 3B conditioned media as a source of murine interleukin (IL)-3. Cells that express ErbB1, ErbB3, ErbB1 + 3 and ErbB2 + 3 were gifts of Prof. E. van Zoelen (Rad-boud University Nijmegen, The Nether-lands). All other ErbB-engineered cell lines were derived from these and from parental 32D cells (a gift of B Guinn, King’s College London, UK) by retroviral transduction with SFG-ErbB2 and/or SFG-ErbB4 and/or by transfection with pcDNA3-ErbB1/3. Cells engineered to ex-press ErbB2 were immunoselected using the Institute of Cancer Research (ICR) rat

monoclonal antibody ICR12 followed by sheep anti-rat immunoglobulin (Ig)-coated para magnetic beads (Invitrogen, Paisley, UK). Cells engineered to express ErbB4 were selected by IL-3–independent growth in heregulin (HRG)-1β(Sigma Aldrich, Poole, UK) (39).

Tumor Cell Lines

All tumor cell lines were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium + 10% FCS and were sourced as follows. HN3 and HN4 cell lines were obtained from the Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research, London. PJ34 cell lines were obtained from the European Collection of Cell Cultures. The 006/1 and 015B cell lines were established in-house (by C Box and SA Eccles). CAL27 cell lines were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection. Vβ6, H357, Detroit 562, HSC3, BiCR56 and BiCR6 were gifts from Professor G. Thomas (Uni-versity of Southampton, UK). All breast/ mammary cancer cell lines and MDA-MB-435 cells were from the Can-cer Research U.K. organization (Lon-don, UK).

Culture and Transduction of Primary Human T Cells

Human peripheral blood mononuclear cells were obtained from the U.K. Na-tional Blood Service, healthy volunteers or patients with squamous cell carci-noma of the head and neck (SCCHN) under approval of the Guy’s and St Thomas’ Research Ethics Committee (ref-erences 09/H0804/92 and 09/H0707/86, respectively). Gene transfer was per-formed exactly as described (36). There-after, T cells were propagated in RPMI 1640 + 10% human AB serum (Sigma-Aldrich) + IL-2 (100 U/mL; Aldesleukin, Novartis, Camberley, UK) or, where indi-cated, IL-4 (30 ng/mL; GMP grade from Gentaur [Kampenhout, Belgium] or re-search grade from Peprotech [Rocky Hill, NJ, USA]).

Flow Cytometry Analysis

Flow cytometry was performed using a Coulter EPICS XL cytometer with Expo32

ADC software or a FACScalibur cytome-ter with Cellquest Pro software. Expres-sion of T1E28z, T1NA and EGF28z was demonstrated using the following: (a) mouse antihuman EGF monoclonal anti-body (clone 10825; R&D Systems, Abing-don, UK) followed by phycoethrin (PE)-conjugated goat anti-mouse Ig (Dako, Ely, UK) or (b) goat EGF polyclonal anti-serum (R&D Systems), followed by fluo-rescein isothiocyanate–conjugated rabbit–anti-goat IgG (Dako). Expression of human ErbB family members was demonstrated using rat anti-ErbB1 (ICR62 clone), rat anti-ErbB2 (ICR12 clone, both ICR antibodies were gener-ated in-house at ICR, Sutton, Surrey, UK), mouse anti-ErbB3 (clone H3.105.5; Neo-markers, ThermoFisher Scientific, Lough-borough, UK) and mouse anti-ErbB4 (clone H4.77.16; Neomarkers), followed by PE-conjugated secondary antibodies (Invitrogen, Paisley, UK). Blockade of Fc receptors was achieved using swine or rabbit serum (Dako). Conjugated anti-bodies were absorbed in the appropriate serum before addition to cells.

Protein Analysis

Electrophoresis was performed under reducing conditions using a 6% (ErbB3) or 8% acrylamide (CD3ζ) resolving gel. West-ern blots were probed with anti-CD3ζ (clone 8D3; BD Pharmingen, Oxford, UK [36]), rabbit anti-ErbB3 antiserum or goat anti-lamin (both from Santa Cruz Biotech-nology, Heidelberg, Germany).

In Vitro Assessment of Antitumor Activity

Engineered T cells (1 ×106cells) were cocultivated with confluent tumor mono-layers in 24-well plates for the indicated period, after which monolayers were stained with crystal violet as described (38). Monolayers were viewed using a Zeiss Axiovert S100 microscope with an AxioCam HR camera. Supernatants har-vested from T-cell tumor monolayer co-cultures were analyzed for interferon (IFN)-γor IL-2 using paired antibody sets (R&D Systems) or using cytokine bead arrays (BD human Th1/Th2/Th17 kit;

BD Biosciences, Oxford, UK), as de-scribed by the manufacturers. Unless oth-erwise stated, T-cell cultures were main-tained in IL-2 (100 U/ mL, added from 24 h after initiation of cultures). Where indicated, T cells were restimulated peri-odically by culture with fresh tumor monolayers. Viable T-cell number was determined by trypan blue exclusion.

Four-hour cytotoxicity assays were performed by measurement of lactate de-hydrogenase release (Roche Applied Sci-ence, Burgess Hill, UK), as described (36). Tumor cell killing was also quanti-fied using a Cell Proliferation Kit II (Roche Applied Science). In that case, 1 ×106T cells were cocultivated with a confluent monolayer (24-well plate, 1.9 cm2) of tumor cells for the indicated period. After the removal of nonadherent T cells, viable tumor cells were then in-cubated with 2,3-bis(2-methoxy-4-nitro- carboxanilide inner salt (XTT) as described by the manufacturer. Comparison was made with a confluent monolayer that had not been cultivated with T cells. The percentage of viable cells remaining was determined by measurement of ab-sorbance measured at 492 nm, using 690 nm as the reference wavelength.

In Vivo Assessment of Efficacy All in vivoexperimentation strictly adhered to current U.K. Home Office guidelines, as stated in the project license (license number 70/6677) and personal license (license number 70/21581) that governed this work.

were mechanically disaggregated before immunostaining as above.

Model 2.The MDA-MB-435 cell line was retrovirally engineered to coexpress firefly luciferase, MUC1 and ErbB2. Tumor cells (5 ×106cells) were inoculated intraperitoneally into 20 SCID Beige mice. Human T cells were engineered to express T4 and then expanded for 2 wks by using IL-4 (38). After 3 d, mice were treated with PBS, IL-4 (125 ng ×three

doses per week), 2 ×107T4+T cells or the combination of T4+T cells + IL-4.

In each case, BLI was performed at the indicated time points using Xenogen IVIS Imaging System (Xenogen) with Living Image software (Xenogen). Mice were in-jected intraperitoneally with D-luciferin (150 mg/kg; Xenogen) and imaged under isoflurane anesthesia after 10 min. Image acquisition was conducted on a 15- or 25-cm field of view with small binning for exposure times of 1–300 s. Animals were inspected daily and sacrificed when ex-perimental endpoints had been achieved or when symptomatic as a result of tumor progression (whichever sooner).

Imaging of HN3 Tumor Xenografts by Using Positron Emission Tomography

Mice with IP HN3 xenografts were de-prived of food for 1 h, anesthetized using isoflurane and maintained on a heating pad for 20 min before intra-venous (IV) injection of 4–7.6 mBq 18

F-fluorodeoxy glucose. Imaging was performed using a Siemens Inveon MicroPET/CT (positron emission to-mography/computerized tomography). A CT attenuation scan was performed followed by a 200-min PET scan. Images were coregistered, and data were recon-structed to generate a three-dimensional image using an OSEM2D reconstruction algorithm (Inveon acquisition workshop software package).

Statistical Analysis

Datasets were analyzed with Graphpad Prism software (version 5), using two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) (for grouped analyses) or two-tailed Student ttest (for comparison of two groups).

All supplementary materials are available online at www.molmed.org.

RESULTS

Engineering of a Chimeric Antigen Receptor with Reactivity against Multiple ErbB Dimer Species

To engineer a broad specificity CAR targeted against relevant ErbB dimers,

T1E sequences were placed upstream of CD28 (hinge/transmembrane/ endodomain) and CD3ζendodomain motifs (36). The resultant fusion receptor (T1E28z) was compared with two control CARs, in which an EGF targeting moiety (EGF28z) or a truncated endodomain were used (T1E no activation domain [T1NA]; see Figure 1C).

Expression of T1E28z and control CARs was detected in T cells by using an anti-EGF antibody (Figure 2A) at propor-tionate levels in CD4+and CD8+subsets (Figure 2B). Integrity and molecular mass of the CAR was determined by Western blotting (Figure 2C).

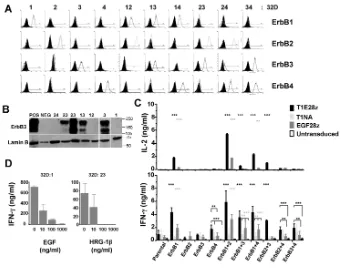

To evaluate targeting specificity, ErbB-negative 32D hematopoietic cells were engineered to express ErbB1–4 (39), ei-ther individually or in all possible binary combinations (Figure 3A). Owing to weak cross-reactivity of the anti-ErbB3 antibody with ErbB2 on 32D cells (for ex-ample, row 3, column 9), expression of this family member was confirmed by Western blotting (Figure 3B). Cocultiva-tion experiments demonstrated that T1E28z mediates T-cell recognition of 32D cells that express all possible ErbB1-based homodimers and heterodimers, leading to production of IL-2 and IFN-γ (Figure 3C). Targeting of ErbB1/2 het-erodimers was consistently achieved most efficiently (P < 0.0001). Importantly, we observed that T1E28z also directed T-cell specificity against the ErbB2/3 het-erodimer, but not against ErbB2 or ErbB3 alone. Weaker targeting of ErbB4 and other ErbB4-containing dimers was also observed. By contrast, EGF28z only tar-gets T cells against ErbB1+32D cells and was less efficient in this respect than T1E28z (P < 0.0001). As anticipated, con-trol (untransduced or T1NA+) T-cell pop-ulations were not activated under these conditions. Targeting specificity was con-firmed further by the ability of EGF and HRG-1βto inhibit competitively the acti-vation of T1E28z+T cells by ErbB1 and ErbB2/3 heterodimers, respectively (Fig-ure 3D). Together, these data demon-strate that T1E28z effectively targets human T cells against several ErbB

dimer species that are commonly over-represented in diverse solid tumors.

Human T Cells Transduced with T1E28z Exhibit Broad Reactivity against Head and Neck Cancer Cell Lines

To evaluate antitumor activity of T1E28z, we focused initially on SCCHN. A panel of 12 SCCHN tumor lines was characterized for expression of ErbB1–4 (Figure 4A). As anticipated from studies of SCCHN in humans (5), all cell lines expressed ErbB1 and were commonly positive for ErbB2 and/or ErbB3 but not ErbB4.

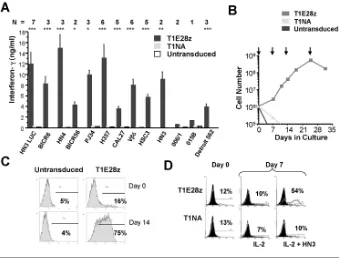

T-cells that express T1E28z or appropri-ate controls were cocultivappropri-ated with a

con-fluent monolayer of all SCCHN tumor cells. In each case, selective destruction of ErbB+tumor monolayers was achieved by T1E28z+but not by control T cells (Figures 4B, C). Activation of T1E28z+ T cells was accompanied by production of IFN-γ(Figure 5A), proliferation (Figure 5B and Supplementary Figure 1) and enrich-ment (Figure 5C), in a manner that re-quired an ErbB-permissive tumor mono-layer and a signaling- competent CAR endodomain (Figure 5D). By contrast, tumor cells that express ErbB3 together with low levels of ErbB1 and ErbB2 (for example, MDA-MB-435; Figure 4A) were recognized poorly (Figure 4B), leading to very-low-level cytokine production

(Sup-plementary Figure 2; note that yaxis is calibrated in pg/mL).

Use of an IL-4–Regulated System to Expand and Enrich T1E28z+T Cells Ex Vivo

We have recently described a system whereby IL-4 can be harnessed to achieve selective expansion of gene- modified

cells, acting via an ectopically expressed IL-4Rα/IL-2Rβchimeric cytokine recep-tor (4αβ) (38). When T1E28z is coex-pressed with 4αβ, the resultant T4+T cells are activated by a similar spectrum of ErbB combinations (Figure 6A) and SCCHN tumor cells (Figure 6B and Sup-plementary Figure 3). Marked enrich-ment of ex vivopropagated 4αβ+T cells is achieved by IL-4 (38). Consequently, com-plete SCCHN tumor monolayer destruc-tion is achieved using as few as 0.25 mil-lion T4+T cells, representing an

effector:target ratio of <1 (Figure 6C). Once again, MDA-MB-435 tumor cells elicited very weak or no activation of T4+ T cells (Figures 6C, E). Although ex-panded in IL-4, T4+T cells do not exhibit type 2 polarization. Upon activation by SCCHN tumor monolayers, they produce much IFN-γand IL-2, but small amounts of IL-4 (Figure 6D). Moreover, production of IFN-γby activated T4+T cells is further enhanced by exogenous IL-4 (Figure 6E).

Therapeutic Efficacy of T1E28z-Transduced T Cells against a Slowly Progressive SCCHN Xenograft

To test efficacy in vivo, human SCCHN was modeled in SCID Beige mice using firefly luciferase–expressing HN3 tumor cells (HN3-LUC) (37). After IP inocula-tion, discrete tumors (typically one to three) grew insidiously. By using PET scanning, we observed that these tumors were poorly avid for 18 F-fluorodeoxyglu-cose, and a thin rim of peripheral uptake was observed, reflecting their tendency for indolent growth and central necrosis (Figure 7A). By contrast, HN3-LUC tu-mors could be readily imaged using bio-luminescence (Figures 7A, B). Impor-tantly, established tumors retained expression of ErbB1 and ErbB2

(Fig-Figure 3.ErbB specificity of the T1E28z CAR. (A) ErbB null 32D myeloid cells were engineered to express all 10 ErbB receptor/dimer combinations. Expression of the indicated ErbB recep-tor was detected by FACS (filled histogram represents staining of parental 32D cells with the same antibody combination) and, in the case of ErbB3, by Western blotting (B). (C) To de-fine targeting specificity, 1 ×106of the indicated engineered T-cell populations was

coculti-vated with an equal number of 32D cells that express the specified ErbB receptor(s). Super-natants were harvested at 24 h (IL-2) and 72 h (IFN-γ) for ELISA analysis. Data shown are mean ± standard deviation (SD) of three (IL-2) or six (IFN-γ) replicates after correction for transduction efficiency between groups. ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01, comparing T1E28z (black) or EGF28z (gray) with other control groups. (D) 32D cells that express ErbB1 (32D:1) or ErbB2 + 3 (32D:23) were cocultivated with T1E28z+T cells in the presence of exogenous EGF (left) or

ure 7C). Although HN3-LUC xenografts also grew after subcutaneous inocula-tion, this model proved unsuitable for testing therapeutic efficacy. The reason was that tumors progressed with unpre-dictable kinetics and were commonly fractured after intratumoral injection.

To test therapeutic efficacy, mice with 13 d established HN3-LUC tumors were treated intraperitoneally with PBS or 20 million T1E28z+or T1NA+T cells. A fourth group received T4+T cells, admin-istered at a dose of 20 or 7.5 million cells. Characterization of T cells before infu-sion confirmed that they were trans-duced and functionally active in vitro (Supplementary Figure 4). After adoptive transfer of immunotherapy, each group was examined using bioluminescence

imaging over 4 months (mean values shown in Figure 7D). Data pertaining to the T4+T cell–treated group were pooled, since animals treated with either dose re-sponded similarly (Supplementary Fig-ure 5). FigFig-ure 7E shows serial imaging of the same mouse in each group, selected as that which gave the median biolumi-nescence emission for the longest period throughout the study. Observations from each mouse at all time points are shown in Figure 7F. One mouse in the T1E28z group developed respiratory distress on d 78 and was culled. Necropsy revealed a centrally placed intrathoracic tumor (presumed thymoma) in the absence of macroscopically evident intra peritoneal disease or bioluminescence signal (Fig-ure 7F).

Significant differences in biolumines-cence emission between mice treated with PBS and either T1E28z+or T4+ T cells became manifest on d 100 and in-creased thereafter. Control T1NA+T-cells exerted intermediate antitumor activity, which may reflect the capacity of this truncated CAR to promote T-cell colocal-ization with tumor cells. Significant dif-ferences between mice treated with T1NA+T cells versus either T1E28z+or T4+T cells were observed at d 128 (Fig-ure 7D). Upon completion of this end-point, the study was terminated.

Antitumor Activity of T1E28z-Transduced T Cells in Breast Cancer

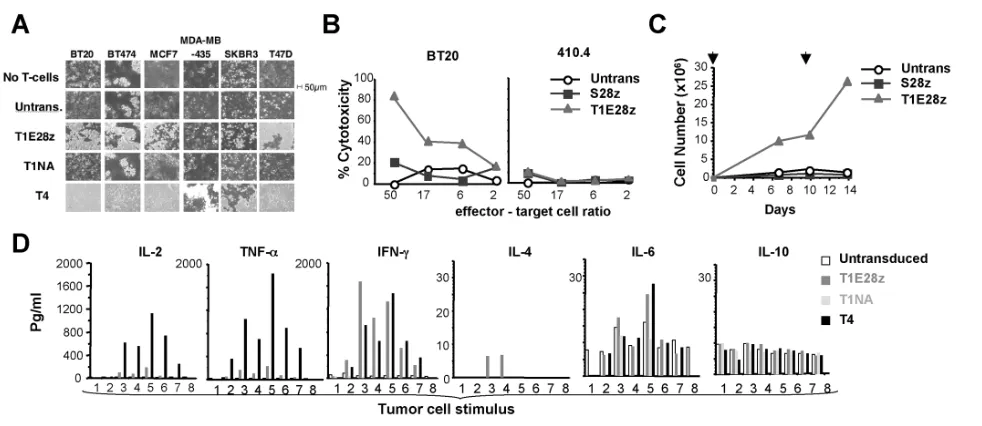

To investigate potential utility in other malignancies, in vitrostudies were

per-Figure 4.T1E28z engineered T cells destroy human head and neck cancer cells. (A) Twelve human SCCHN cell lines (and MDA-MB-435 control cells) were analyzed for cell surface expression of ErbB1–4 by FACS. Staining with the indicated ErbB-specific (open histogram) or isotype control (filled histogram) antibody is indicated. (B) Confluent monolayers of the indicated tumor cell lines (24-well plate, 1.9 cm2) were cocultivated with 1 ×106T1E28z+T cells. Control T cells expressed T1NA (a matched endodomain-truncated CAR) or were

untrans-duced (Untrans.). After 72 h, residual monolayers were fixed and stained with crystal violet. Punctate staining in T1E28z wells represents adherent lymphocytes. (C) One million of the indicated T-cell populations were cocultivated overnight with a confluent 1.9-cm2

formed with human breast and murine mammary carcinoma cell lines that express diverse ErbB profiles (Supplementary Fig-ure 6). In addition to previously described controls, comparison was also made with an endodomain-matched control CAR named S28z (37). Activation of T1E28z+but not control T cells was observed upon cul-ture with several of the breast cancer cell lines, resulting in monolayer destruction (Figure 8A), cytotoxicity (Figure 8B), T-cell proliferation (Figure 8C and Supplemen-tary Figure 7) and cytokine production (Figure 8D). By contrast, ErbBl° murine tar-get cells (410.4, Supplementary Figure 6) only weakly activated T1E28z+T cells (Supplementary Figure 2) and were not killed efficiently (Figure 8B). Owing to

IL-4– mediated preenrichment (for exam-ple, Supplementary Figure 4), destruction of breast tumor cell monolayers was con-sistently achieved more efficiently by T4+ than T1E28z+T cells (Figure 8A). Activated T4+T cells once again produced a predom-inance of type 1 cytokines (Figure 8D and Supplementary Figure 8).

Therapeutic Activity against an Aggressive ErbB2/3-Expressing Tumor Xenograft

Next, we evaluated therapeutic effi-cacy in vivo in a tumor model character-ized by overexpression of the potently mitogenic ErbB2/3 heterodimer. We pre-viously showed that luciferase/MUC1 coexpressing MDA-MB-435 (MUC-LUC)

cells establish a robust and aggressive IP cancer model (37). However, because these tumor cells only express ErbB3 to-gether with low levels of ErbB2 (Fig-ure 4A), they are targeted inefficiently by T1E28z+and T4+T cells (Figure 8A; Figure 8D, tumor cell number 2). On the basis of our in vitrostudies, we hypothe-sized that efficient targeting would be achieved if these tumor cells coex-pressed high levels of ErbB2. To test this, ErbB2-overexpressing MUC-LUC tumor cells were engineered (Figure 9A) and then established as IP xenografts. Ani-mals with established tumors were treated with T4+T cells after ex vivo ex-pansion in clinically compliant condi-tions using IL-4 (38). Comparison was made between groups treated with T4+ T cells alone or together with exogenous IL-4. Control animals received PBS or IL-4 alone. We observed that T4+T cells achieved striking control of this highly aggressive tumor (Figure 9B). Further benefit was gained when a combination of T4+T cells and IL-4 were used, with mice harboring a significantly lower tumor burden than animals treated with T4+T cells alone (Figure 9C). The reason for this result is currently unclear. One possibility is that the provision of IL-4 favors in vivo persistence of the T4+T cells, thus permitting further growth re-tardation of the tumor. However, be-cause the use of IL-4 alone induced some (although not significant) thera-peutic activity (Figure 9B), improved tumor control may alternatively reflect an additive effect of the two therapies.

DISCUSSION

Coordinated activation of the ErbB family plays a fundamental role in devel-opment and is commonly subverted dur-ing tumorigenesis. Most often, such aber-rant ErbB activity results from the upregulated expression and/or activa-tion of one or more family members, no-tably ErbB1 and/or ErbB2. Increased sig-naling by mutually cooperative ErbB heterodimers (particularly ErbB2/ErbB3) is also a frequent property of solid tu-mors, notably HER2-amplified breast

Figure 5.T1E28z engineered T cells are activated by human head and neck cancer cells. (A) Confluent head and neck tumor monolayers (24-well plate, 1.9 cm2) were coculti-vated with 1 ×106of the indicated T-cell populations. Supernatants were harvested after

cancer (7). Tumors that display ErbB up-regulation are generally associated with worsened prognosis (1–3). Consequently, targeted therapies directed against this family occupy an increasing niche in can-cer therapy and drug development.

In this study, we have pursued an im-munotherapeutic approach to exploit the prevalence of ErbB overexpression in cancer. We hypothesized that potent and

yet safe antitumor immunity could be achieved by directing T-cell specificity simultaneously against key ErbB dimer units that commonly drive tumorigene-sis. This strategy contrasts with previ-ously reported immunotherapeutic ap-proaches directed against individual ErbB family members (40,41) and was chosen for two main reasons. First, tu-mors commonly acquire therapeutic

re-sistance to ErbB-directed therapies through upregulated activation of non-targeted family members (20–25,42). In keeping with this, several precedents il-lustrate how combined targeting of two or more ErbB receptors can achieve im-proved antitumor activity (24,25,27). Sec-ond, we reasoned that harnessing of the multiple effector mechanisms deployed by T cells would elicit more potent and

Figure 6.In vitro activation of T4+

human T cells. Human T cells were engineered to coexpress the IL-4–responsive 4αβchimeric cytokine receptor together with the T1E28z CAR (combination called “T4”). After expansion in IL-4, comparison was made with control T cells that were untransduced (Untrans) or that express T1NA (truncated endodomain). (A) To define targeting specificity for ErbB receptors/dimers, 1 ×106of the indicated T-cell populations were cocultivated with an equal number of 32D cells that express the specified ErbB

recep-tor(s). Supernatants were harvested at 72 h and analyzed for interferon (IFN)-γ(mean ± SD; ***P < 0.001; **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05). (B) 1 ×106 T cells were cocultivated with confluent monolayers of the indicated head and neck tumor cells cultured in 24-well (1.9-cm2) plates.

prompt antitumor efficacy, when com-pared with the cytostatic or indirectly lytic capabilities of other ErbB targeted therapies. As a result, less time is granted to tumor cells to evolve independent resistance mechanisms.

To test this concept, we developed a CAR named T1E28z that incorporates a promiscuous ErbB ligand as a targeting moiety. We demonstrated that the T1E28z fusion receptor can engage ErbB1 homodimers and heterodimers in addition to the ErbB2/3 mitogenic unit. The greatest targeting activity was demonstrated against cells that coex-press ErbB1 and ErbB2. Unexpectedly,

when tested using cells that express ErbB1 alone, T1E28z mediated enhanced T-cell activation compared with a matched fusion in which specificity was directed by EGF. Targeting of tumor cells by the T1E28z CAR was repeatedly demonstrated both in vitro andin vivo, using several cell lines representative of two distinct ErbB-associated solid tu-mors, namely head and neck cancer and breast cancer. In unpublished studies, we have shown that T-cells engrafted with this fusion can also destroy cell lines derived from other common solid tumor types (data not shown). Further-more, antitumor activity was apparent

against target cells that express a spec-trum of ErbB expression profiles. The recognition and destruction of the T47D cell line, which expresses ErbB2 and ErbB3, but minimal ErbB1 (43), strength-ens the evidence that T1E28z can engage ErbB2/3 hetero dimers on tumor cells. In vivotherapeutic efficacy was demon-strated in models of both slow-growing and rapidly progressive tumor types, driven by ErbB1 or ErbB2/3 signaling, respectively. Together, these findings demonstrate the flexible therapeutic value of this approach.

A key concern with systemic therapies targeted against ErbB receptors is the

Figure 7.In vivo antitumor activity of T1E28z-transduced T cells against a slowly progressive head and neck tumor xenograft. (A) HN3 tumor cells were engineered to express firefly luciferase (HN3-LUC) and were propagated as IP xenografts. In this representative example, a large established tumor was imaged by PET using 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (tumor center indicated by crosshairs) or BLI, following

admin-istration of luciferin. (B) Five mice were inoculated intraperitoneally with 5 ×106HN3-LUC tumor cells and analyzed by BLI at the indicated

intervals. (C) HN3-LUC tumors were recovered from mice described in (B) and analyzed by FACS for expression of ErbB1 and ErbB2. Com-parison was made with HN3-LUC cells cultured in vitro. Filled histograms show staining with isotype control alone. (D) Twenty-five SCID Beige mice were inoculated with 5 ×106HN3-LUC tumor cells, administered by the IP route. Tumor take was confirmed on d 8 by BLI. On

d 13, mice were treated with T cells transduced with T1E28z (n = 7), T1NA (n = 6), T4 (combination of 4αβand T1E28z; n = 6) or PBS (n = 6). Analysis of T cells before infusion is shown in Supplementary Figure 4. Mean bioluminescence for each group is shown over the course of the study. ***P < 0.001 (T1E28z versus PBS and T4 versus PBS); *P < 0.05 (T1E28z versus PBS and T4 versus PBS); ‡P < 0.001 (T4 versus PBS) and

P < 0.01 (T1E28z versus PBS); ‡‡P < 0.001 (T4 versus T1NA) and P < 0.01 (T1E28z versus T1NA). (E) Serial imaging of the same mouse (median

risk of unacceptable toxicity. Four prece-dents provide reassurance in this regard. First, ErbB-specific T cells are present at increased frequency in patients with di-verse solid tumors (44). Second, immu-nization against ErbB2 has been opti-mized to a point where clinical and immunologic responses occur in the ab-sence of significant toxicity (45). Third, extensive clinical experience has con-firmed the safety of monoclonal antibod-ies and small molecules directed against the ErbB family, particularly ErbB1 and ErbB2 (46). Fourth, IV infusion of ErbB2-specific CD8+T-cell clones has been con-ducted in patients with metastatic HER2-positive breast cancer, without significant toxicity (47).

Against this favorable background, Morgan et al.(48) recently treated a pa-tient with metastatic colorectal cancer using autologous T cells, retargeted with a high affinity ErbB2-specific CAR that contained a fused CD28/4-1BB/CD3ζ endodomain. Treatment involved

lympho-depletion following by IV ad-ministration of 1010cells (79% CAR+). Unfortunately, however, the patient rap-idly succumbed to adult respiratory dis-tress syndrome followed by multiorgan failure—an event that was clearly attrib-utable to the infused T-cells. This inci-dent mandates a highly careful approach to the systemic administration of targeted T cells in humans.

Mindful of these issues, we set out here to develop a distinct immunothera-peutic approach to deliver selective toxi-city against cancers that are driven by aberrant ErbB signaling. Importantly, whereas the T1E28z CAR can engage several tumor-associated ErbB dimers, it does not bind to ErbB2 or ErbB3 alone. Furthermore, it is not activated effi-ciently by cells that express low levels of one or more ErbB receptors (for example, MDA-MB-435 cells). In keeping with this, we observed no overt clinical evi-dence of toxicity in any of over 40 mice treated with human T1E28z-engineered

T-cells. This observation is important for two reasons. First, similar to all known human ErbB ligands, human T1E and the derived human T1E28z CAR can engage murine ErbB receptors (data not shown). Second, despite many species-specific differences, activated human T cells can trigger lethal immunopathology in mice, for example, during xenogeneic graft versus host disease. To evaluate this fur-ther, we are currently undertaking rigor-ous toxicity studies to investigate possi-ble “on-target, off-organ” effects in vivo, using both immune competent and im-munocompromised hosts. The former approach is of particular importance, since several potentially immunosup-pressive mechanisms cannot be modeled in SCID Beige mice. These include the in-fluence of myeloid suppressor cells and regulatory T cells.

In vivo studies were performed using IP tumor models, whereby T-cells were administered to the peritoneal cavity. We selected this option because we

previ-Figure 8.In vitro antitumor activity of T1E28z+T cells against breast cancer. (A) 1

×106human T cells engineered to express the indicated

CARs were cocultivated with confluent breast cancer monolayers, cultured in 24-well (1.9-cm2) plates. After 24 h, nonadherent cells were

removed and monolayers were fixed and stained with crystal violet. (B) Four-hour lactate dehydrogenase release cytotoxicity assay in which T1E28z+or control S28z+T cells were cultured with BT20 breast cancer cells or ERBBl° 410.4 mammary carcinoma cells. (C) A

repre-sentative experiment in which T1E28z+and S28z+T cells were cultured with BT20 breast cancer cells. After 24 h, IL-2 was added.

Restimula-tion on a confluent BT20 monolayer was performed where indicated by the overhead arrows. T cells were enumerated at the indicated intervals. (D) Transduced T cells were cocultivated in 24-well plates with confluent monolayers or suspension cells as follows: 1) Jurkat (control; 1 ×106cells); 2) MDA-MB-435; 3) BT20; 4) BT474; 5) MCF7; 6) SKBR3; 7) T47D; 8) medium alone. Supernatants were analyzed for

ously found that IV-administered human T-cells migrate with delayed kinetics via the pulmonary circulation and thereafter redistribute to liver, spleen and lymph nodes. However, trafficking to either subcutaneous or intraperitoneal xeno -grafts was poor. This challenge to clinical translation is discussed extensively by Parente-Pereira et al.(49). In light of this, we are planning clinical studies in which these T cells are delivered using a re-gional approach.

CONCLUSION

In summary, the conceptual and thera-peutic advance reported here is a flexible and robust immunotherapy directed against ErbB dimers that drive several solid tumor types and commonly medi-ate therapeutic resistance. Therapeutic efficacy is consistently achieved both in vitro and in vivoagainst tumors of vari-ous lineages, highlighting the potential applicability of this approach to a wide range of malignancies. A clinical trial will

follow shortly in patients with SCCHN, treated by intratumoral delivery after lo-coregional recurrence. Such studies will pave the way for systemic targeting, thereby harnessing for therapeutic gain the primacy of ErbB overexpression in several human tumors.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Asso-ciation for International Cancer Research (Project Grant 08-0419), Breast Cancer Campaign (Project Grant 2006NovPR18), Guy’s and St Thomas’ Charity, Experi-mental Cancer Medicine Centre (King’s College London). Phase 1 testing of this immunotherapy was supported by the Moulton Charitable Foundation and by Guy’s and the Department of Health via the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre based at Guy’s and St Thomas’ National Health Service (NHS) Foundation Trust and King’s College London. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health. C Box was funded by the Oracle Cancer Trust at the Royal Marsden Hospital. The research of SA Eccles was funded by ICR and Cancer Research UK grant CA309/ A8274 and funding provided via the NIHR specialist BRC award to the Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust in part-nership with the Institute of Cancer Re-search. We thank colleagues who have generously provided materials that facili-tated this work, as indicated in the text.

DISCLOSURE

The authors declare that they have no competing interests as defined by Molec-ular Medicine, or other interests that might be perceived to influence the re-sults and discussion reported in this paper.

REFERENCES

1. Arteaga CL. (2003) ErbB-targeted therapeutic approaches in human cancer. Exp. Cell Res.

284:122–30.

2. Citri A, Yarden Y. (2006) EGF-ERBB signalling: towards the systems level. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol.7:505–16.

A

Figure 9.In vivo activity of T1E28z+

T cells against an ErbB2/3-expressing aggressive tumor xenograft. (A) MDA-MB-435 cells were engineered to coexpress MUC1, ErbB2 and firefly lu-ciferase (MUC-LUC ERBB2). FACS plots show staining with ErbB-specific (open histograms) and isotype control antibodies (filled histograms). (B) MUC-LUC ErbB2 tumor cells were in-oculated intraperitoneally in 20 SCID Beige mice. After 3 d, mice (n = 5 per group) were treated with PBS, IL-4 (125 ng ×3 doses per wk), 2 ×107T4+T cells or the combination of T4+

3. Hynes NE, MacDonald G. (2009) ErbB receptors and signaling pathways in cancer. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol.21:177–84.

4. Morgan S, Grandis JR. (2009) ErbB receptors in the biology and pathology of the aerodigestive tract. Exp. Cell Res.315:572–82.

5. Rogers SJ, Harrington KJ, Rhys-Evans P, Charoenrat O, Eccles SA. (2005) Biological signif-icance of c-erbB family oncogenes in head and neck cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev.24:47–69. 6. Foley J, et al.(2010) EGFR signaling in breast

cancer: bad to the bone. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol.

21:951–60.

7. Holbro T, et al.(2003) The ErbB2/ErbB3 het-erodimer functions as an oncogenic unit: ErbB2 requires ErbB3 to drive breast tumor cell prolifer-ation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A.100:8933–8. 8. Hirsch FR, Varella-Garcia M, Cappuzzo F. (2009)

Predictive value of EGFR and HER2 overexpres-sion in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer.

Oncogene.28 (Suppl. 1):S32–37.

9. Lockhart AC, Berlin JD. (2005) The epidermal growth factor receptor as a target for colorectal cancer therapy. Semin. Oncol.32:52–60. 10. Hammarsten P, et al.(2010) Low levels of

phos-phorylated epidermal growth factor receptor in nonmalignant and malignant prostate tissue pre-dict favorable outcome in prostate cancer pa-tients. Clin. Cancer Res.16:1245–55.

11. Jathal MK, Chen L, Mudryj M, Ghosh PM. (2011) Targeting ErbB3: the new RTK(id) on the prostate cancer block. Immunol. Endocr. Metab. Agents Med. Chem.11:131–49.

12. Bellone S, et al.(2007) Overexpression of epider-mal growth factor type-1 receptor (EGF-R1) in cervical cancer: implications for mediated therapy in recurrent/metastatic dis-ease. Gynecol. Oncol.106:513–20.

13. Sheng Q, et al.(2010) An activated ErbB3/NRG1 autocrine loop supports in vivo proliferation in ovarian cancer cells. Cancer Cell17:298–310. 14. Liles JS, et al.(2010) ErbB3 expression promotes

tumorigenesis in pancreatic adenocarcinoma.

Cancer Biol. Ther.10:555–63.

15. Jhabvala-Romero F, Evans A, Guo S, Denton M, Clinton GM. (2003) Herstatin inhibits heregulin-mediated breast cancer cell growth and over-comes tamoxifen resistance in breast cancer cells that overexpress HER-2. Oncogene.22:8178–86. 16. Wang S, Huang X, Lee CK, Liu B. (2010) Elevated

expression of erbB3 confers paclitaxel resistance in erbB2-overexpressing breast cancer cells via upregulation of Survivin. Oncogene29:4225–36. 17. Liang K, Ang KK, Milas L, Hunter N, Fan Z.

(2003) The epidermal growth factor receptor me-diates radioresistance. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys.57:246–54.

18. Olayioye MA, Neve RM, Lane HA, Hynes NE. (2000) The ErbB signaling network: receptor het-erodimerization in development and cancer.

EMBO J.19:3159–67.

19. Baselga J, Swain SM. (2009) Novel anticancer tar-gets: revisiting ERBB2 and discovering ERBB3.

Nat. Rev. Cancer.9:463–75.

20. Erjala K, et al.(2006) Signaling via ErbB2 and ErbB3 associates with resistance and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) amplification with sensitivity to EGFR inhibitor gefitinib in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cells. Clin. Cancer Res.12:4103–11.

21. Garrett JT, et al.(2011) Transcriptional and post-translational up-regulation of HER3 (ErbB3) compensates for inhibition of the HER2 tyrosine kinase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A.108:5021–6. 22. Jain A, et al.(2010) HER kinase axis receptor dimer

partner switching occurs in response to EGFR ty-rosine kinase inhibition despite failure to block cellular proliferation. Cancer Res.70:1989–99. 23. Kruser TJ, Wheeler DL. (2010) Mechanisms of

re-sistance to HER family targeting antibodies. Exp. Cell Res.316:1083–100.

24. Ritter CA, et al.(2007) Human breast cancer cells selected for resistance to trastuzumab in vivo overexpress epidermal growth factor receptor and ErbB ligands and remain dependent on the ErbB receptor network. Clin. Cancer Res.13:4909–19. 25. Sergina NV, et al.(2007) Escape from HER-family

tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy by the kinase-inactive HER3. Nature.445:437–41.

26. Zhou BB, et al.(2006) Targeting ADAM-mediated ligand cleavage to inhibit HER3 and EGFR path-ways in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Cell.

10:39–50.

27. Schaefer G, et al.(2011) A two-in-one antibody against HER3 and EGFR has superior inhibitory activity compared with monospecific antibodies.

Cancer Cell.20:472–86.

28. Hickinson DM, et al.(2010) AZD8931, an equipo-tent, reversible inhibitor of signaling by epider-mal growth factor receptor, ERBB2 (HER2), and ERBB3: a unique agent for simultaneous ERBB receptor blockade in cancer. Clin. Cancer Res.

16:1159–69.

29. Burstein HJ, et al.(2010) Neratinib, an irrevers -ible ErbB receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor, in patients with advanced ErbB2-positive breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol.28:1301–7.

30. Bianco R, et al.(2008) Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-1 contributes to resistance to anti-epidermal growth factor receptor drugs in human cancer cells. Clin. Cancer Res.14:5069–80. 31. Guix M, et al.(2008) Acquired resistance to EGFR

tyrosine kinase inhibitors in cancer cells is medi-ated by loss of IGF-binding proteins. J. Clin. In-vest.118:2609–19.

32. Lai AZ, Abella JV, Park M. (2009) Crosstalk in Met receptor oncogenesis. Trends Cell Biol.

19:542–51.

33. Davies DM, Maher J. (2010) Adoptive T-cell im-munotherapy of cancer using chimeric antigen receptor-grafted T cells. Arch. Immunol. Ther. Exp. (Warsz).58:165–78.

34. Sadelain M. (2009) T-cell engineering for cancer immunotherapy. Cancer J.15:451–5.

35. Wingens M, et al.(2003) Structural analysis of an epidermal growth factor/transforming growth factor-alpha chimera with unique ErbB binding specificity. J. Biol. Chem.278:39114–23.

36. Maher J, Brentjens RJ, Gunset G, Riviere I, Sadelain M. (2002) Human T-lymphocyte cyto-toxicity and proliferation directed by a single chimeric TCRzeta/CD28 receptor. Nat. Biotechnol.

20:70–5.

37. Wilkie S, et al.(2008) Retargeting of human T cells to tumor-associated MUC1: the evolution of a chimeric antigen receptor. J. Immunol.

180:4901–9.

38. Wilkie S, et al.(2010) Selective expansion of chimeric antigen receptor-targeted T-cells with potent effector function using interleukin-4.

J. Biol. Chem.285:25538–44.

39. Wang LM, et al.(1998) ErbB2 expression in-creases the spectrum and potency of mediated signal transduction through ErbB4.

Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A.95:6809–14. 40. Altenschmidt U, et al.(1996) Cytolysis of tumor

cells expressing the Neu/erbB-2, erbB-3, and erbB-4 receptors by genetically targeted naive T lymphocytes. Clin. Cancer Res.2:1001–8. 41. Stancovski I, et al.(1993) Targeting of T

lympho-cytes to Neu/HER2-expressing cells using chimeric single chain Fv receptors. J. Immunol.

151:6577–82.

42. Grovdal LM, et al.(2012) EGF receptor inhibitors increase ErbB3 mRNA and protein levels in breast cancer cells. Cell Signal.24:296–301. 43. Contessa JN, Abell A, Valerie K, Lin PS,

Schmidt-Ullrich RK. (2006) ErbB receptor tyrosine kinase network inhibition radiosensitizes carcinoma cells. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys.65:851–8. 44. Andrade Filho PA, Lopez-Albaitero A, Gooding

W, Ferris RL. (2010) Novel immunogenic HLA-A*0201-restricted epidermal growth factor recep-tor-specific T-cell epitope in head and neck can-cer patients. J. Immunother. 33:83–91.

45. Mittendorf EA, Holmes JP, Ponniah S, Peoples GE. (2008) The E75 HER2/neu peptide vaccine.

Cancer Immunol. Immunother57:1511–21. 46. Dalle S, Thieblemont C, Thomas L, Dumontet C.

(2008) Monoclonal antibodies in clinical oncol-ogy. Anticancer Agents Med. Chem.8:523–32. 47. Bernhard H, et al.(2008) Adoptive transfer of

au-tologous, HER2-specific, cytotoxic T lymphocytes for the treatment of HER2-overexpressing breast cancer. Cancer Immunol. Immunother.57:271–80. 48. Morgan RA, et al.(2010) Case report of a serious

adverse event following the administration of T cells transduced with a chimeric antigen recep-tor recognizing ERBB2. Mol. Ther.18:843–51. 49. Parente-Pereira AC, et al.(2011) Trafficking of