International Community Access

to Child Health Program: 10 Years

of Improving Child Health

Rachel A. Umoren, MB, BCh, MS, a Mohamed A. Mohamed, MD, b Koye A. Oyerinde, MD, c Yvonne E. Vaucher, MD, d Ann T. Behrmann, MD, e Michael Canarie, MD, f Rajesh Dudani, MD, g Mirzada Kurbasic, MD, MS, h

Molly J. Moore, MD, i Alcy R. Torres, MD, j Manuel Vides, MD, MS, k Donna Staton, MD, MPHl

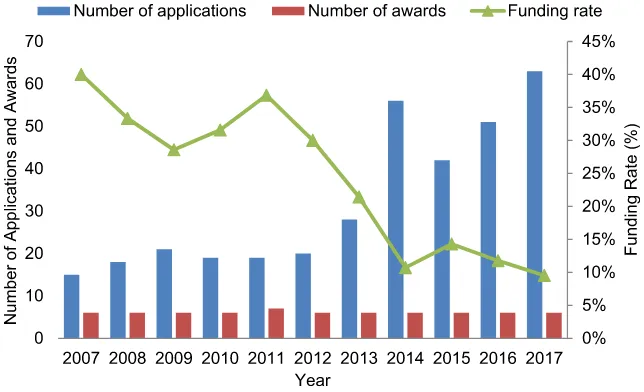

CATCH (Community Access to Child Health) Programs both in the United States and now internationally (ICATCH) have gained enormous popularity. This report chronicles the successful implementation of the Program worldwide. It speaks to the power of small investments in good ideas put forward by providers of hands on care everywhere. The history of success reported here is also demonstrated by the remarkable increase in applications, while the resources made available have only allowed for a relatively flat number of funded programs. When success is obvious and cost effective, why not do more?

Jay Berkelhamer, Editor, Global Health

Feature

Gaps in health care delivery routinely contribute to childhood morbidity and mortality in low- and low-middle–income countries (LLMICs).1 To address these gaps,

global organizations like the World Health Organization partner with national ministries of health to find sustainable solutions. Although generally successful, this high-level approach does not directly engage local providers who have ideas for contextual and culturally appropriate solutions but lack the technical, financial, or other necessary resources to implement projects that promote child health in their own communities.2

In 2006, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) Section on International Child Health, which seeks to promote efforts

to improve and maintain the health and well-being of children throughout the world, 3 launched

the International Community Access to Child Health (ICATCH) program.4 The ICATCH program,

modeled on the successful Community Access to Child Health program, 5 has provided 66 small

grants to health workers in low-resource settings to implement clinical and educational projects that improve the physical, mental, and social wellbeing of children. In addition, ICATCH provides guidance on project design and implementation. Pediatrician members of the Section on International Child Health and the ICATCH review team collaborate with grantees by sharing expertise and resources, starting with the application process, through implementation, and beyond the 3-year funding period. Managed by a diverse team of volunteer pediatricians with expertise in global health, ICATCH receives part-time AAP administrative support. ICATCH grants are financed primarily through donations from AAP members, with additional support from outside donors and foundations.

ICATCH GUIDING PRINCIPLES

ICATCH is based on the principle that local child health workers

aDepartment of Pediatrics, University of Washington, Seattle,

Washington; bDepartment of Pediatrics, Washington University,

Washington, District of Columbia; cCatholic Health Initiative St. Alexius

Health, Minot, North Dakota; dDepartment of Pediatrics, University

of California, San Diego, San Diego, California; eSchool of Medicine

and Public Health, University of Wisconsin, Madison, Wisconsin;

fDepartment of Pediatrics, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut; gDepartment of Pediatrics, University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona; hDepartment of Pediatrics, University of Louisville, Louisville, Kentucky; iDepartment of Pediatrics, University of Vermont, Burlington, Vermont; jDepartment of Pediatric Neurology, Boston University, Boston,

Massachusetts; kUniversidad Dr. Jose Matias Delgado, Antiguo

Cuscatlán, La Libertad, El Salvador; and lSection on International Child

Health, American Academy of Pediatrics, Los Altos Hills, California

DOI: https:// doi. org/ 10. 1542/ peds. 2017- 2848

Accepted for publication Apr 4, 2018

Address correspondence to Donna Staton, MD, MPH, International Community Access to Child Health, Section on International Child Health, American Academy of Pediatrics, 141 NW Point Blvd, Elk Grove Village, IL 60007. E-mail: icatch@ aap.org

PEDIATRICS (ISSN Numbers: Print, 0031-4005; Online, 1098-4275). Copyright © 2018 by the American Academy of Pediatrics

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they

have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

FUNDING: The International Community Access to Child Health

program is funded by the American Academy of Pediatrics.

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors have

indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

To cite: Umoren RA, Mohamed MA, Oyerinde KA, et al.

are best positioned to understand the health challenges in their communities and are uniquely qualified to address them. The following prerequisites must be met for proposals to qualify for funding:

• funded programs must be led by local child–health care providers or educators from LLMICs;

• proposals must improve clinical services for children or provide health education for children, parents, or health care providers and should not solely be focused on research;

• collaboration with community-based organizations, government, schools, or businesses within the target community is strongly encouraged because this

enhances likelihood of uptake and sustainability; and

• proposals must have strong potential for sustainability beyond the grant period and replication in other communities.

THE ICATCH PROCESS

The ICATCH process is designed to be straightforward and accessible to health providers in low-income settings.6 Each fall, a call for

proposals is widely distributed via AAP and other Web sites targeting global health educators and pediatricians in low- and middle-income countries, LISTSERVs, social media, etc. Application materials are downloadable from the ICATCH Web site (www. aap. org/ icatch) along with a detailed instruction booklet. The application is submitted by e-mail rather than an online process specifically to enable those without regular Internet access to apply. Applications meeting all

prerequisites are scored on merit

each year, depending on funding availability. ICATCH grantees are linked with a US-based pediatrician with global health experience who serves as a resource throughout the 3 years of the grant. All funded applicants, as well as those selected to revise and reapply, receive individualized feedback. ICATCH grants need to include simple, straightforward ways to monitor outputs and evaluate project outcomes. A mandatory annual report requires careful self-evaluation of project successes and failures and offers another opportunity for collaboration between grantees and advisors. Project directors who encounter significant challenges in

implementation are encouraged to work with their project advisors to modify plans and overcome obstacles.

ICATCH FUNDED PROJECTS

From 2007 to 2017, ICATCH grants have supported 66 innovative programs in 37 countries, primarily

decreasing from 40% in 2007 to 10% in 2017. See Fig 1.

No preference is given to a specific region or country, but several countries have received multiple awards. For example, 11% of total ICATCH grants have been given to projects in Uganda. Although country classifications and ICATCH grant criteria regarding limiting grant applications to countries designated as LLMICs have changed over time, 82% of ICATCH projects have been conducted by project directors living in countries that are currently classified by the World Bank as LLMICs. In a review of funded grants from 2011 to 2017, 31% of codirectors also resided in LLMICs. ICATCH projects have addressed a wide variety of health needs, including nutrition education, newborn care, immunizations, oral health, autism screening, safety, and the unique needs of adolescents. See Table 1.

The majority of ICATCH-funded projects include community (85%) and provider education (65%). Half

FIGURE 1

TABLE 1 ICATCH-Funded Projects by Country

Continent Country ICATCH-Funded Projects

Asia Afghanistan “Daireyeh Waledin” (Circle of Parents)

Bangladesh Promotion of Child Health in Primary School Cambodia Floating Gardens for Health and Prosperitya

Dental Treatment for Children With Cleft Lip and Palate in Cambodiaa Implementing Helping Babies Breathe in Remote Floating Villages China Rural Children With Diarrhea: Primary Care

Dietary Assessment for Intake of Vitamin A Using Semi-quantitative Food Frequency Questionnaire

Healthy Children ‐ Healthy Community Parent Education for Child Passenger Safety

India Home‐Based Care Program for Infants in Krishnagiri, India Newborn Resuscitation Training

Indonesia Improving, Understanding, and Implementation of IMCI: Urban Community Health Workers Improve Understanding of GOBI FFF

Laos Good Nutrition

Myanmar Targeted Vaccination Opportunities for Children, Hepatitis‐B Preventiona Pakistan Maternal Education to Improve Weaning Diet of Infants in Karachia

Trained Nurses Detect Cases of Child Malnutrition

Improving Child Health Through Maternal Education: The Helping Hands Project Philippines TB DOTs for Kids

Bagong Barangay Project

Vietnam Vietnam - First Aid for Childcare Givers and Teachers (VIET-FACTs)

Africa Angola Sickle Cell Education and Screening for Angolan Adolescents

Botswana HIV/AIDS Education for School Staff

Ethiopia Training Community Health Workers in Ethiopia to Recognize the Signs of Neonatal Illness Using Videosa

Ghana Community Malaria Prevention Project Child Protection in Ghana

Strengthening Community Awareness of Pediatric Poisoning in Ghana Kenya Hospital Linkage With Community Child Health in Kisii, Kenya

Improving Access to Health Care for Street Children Peer Navigators Supporting HIV Treatment for Street Youtha Lesotho General Pediatrics Nurse Training in Lesothoa

Liberia Enhanced Well Child Care for Adolescent Mothers and Infants Developing a Model Medical Home for Liberian Children

Malawi Training Program for Management of Neurodisabled Malawian Children Teenager Support Line, Malawi

Establishing a Pediatric Triage System to Improve Child Health in Mangochi District Hospitala Mozambique Supplemental Nutrition for Infants With Failure‐to‐Thrive in Mozambiquea

Nigeria Balanced Early Nutrition for Development (BEND) Support for Adolescents With HIV in Boarding Schoola Rwanda Growing Health (GH): Hospital-based Farm and Nutritiona South Africa Turn INH Preventive Therapy Into Reality

Uganda The Kayunga Newborn Project

Childhood Epilepsy in Northern Uganda: Children as Health Workers Tackling Malnutrition Through Peer Education in Schools Promoting Adolescent Medicine in Uganda

Community Empowerment in Health‐Plus, Mukonoa

Supporting School‐Centered Asthma Programme (SCAPE) in a Boarding School in Central Ugandaa

School Gardening for Healthy Child Growth and Learninga Zambia Zambian Health Evaluation and Education Project

Asthma Project

Europe Bosnia and Herzegovina Autism Education and Screening

Romania Safe Baby Project

health (12%), child health (19%), adolescents and street youth (17%), and parents (16%). See Fig 2.

ICATCH FUNDING HAS LED TO SUSTAINABLE PROJECTS AND PARTNERSHIPS

ICATCH projects have a high completion rate. In 2017, of the 66 projects funded, 49 of 54 (91%) projects continued for the full 3 years with a submission of a final report, and there were 12 projects in progress. Although modest in amount, ICATCH grants have resulted in the implementation of sustainable and high impact health care projects. Examples of projects that have proven to be sustainable include the following:

- a project codirected by Nakakeeto and Vaucher in 2007 on

“Strengthening Capacity to Care for High Risk Newborns in Rural Uganda: The Kayunga Experience”

informed the Ugandan Ministry of Health Newborn Care Initiative; - a 2011 project codirected by Remetic

and Kurbasic on autism education and early screening led to regional awareness, strong community

capacity building for staff and skills training for patients at a newly established General Adolescent Health Clinic at the Mulago National Referral and Teaching Hospital for Makerere University, Uganda.

BENEFITS BEYOND THE GRANT PERIOD

ICATCH is uniquely positioned to extend professional support to grantees beyond the grant period. For example, grantees have received support to cofacilitate grant-writing workshops at the 2010, 2013, and 2016 International Congress of Pediatrics meetings and to participate in a week-long International Quality Improvement and Leadership Institute workshop. Grantees become part of a growing network of current and past grantees, presenting their work

encourage collaboration among global health faculty and those working in similar fields or facing similar challenges, building the capacity of grantees to be successful in leveraging in-kind support and funding from other sources and strengthening the connections between institutions and communities.

CONCLUSIONS

In 2017, ICATCH celebrated 10 years of successful collaboration with children’s health care providers in low- and middle-income countries. ICATCH grants empower local providers to identify challenges, offer solutions, and organize their communities to achieve better health. Although the increasing competitiveness of ICATCH grants reveals the need for expansion of the program, ICATCH’s decade of success reveals how professional medical organizations can leverage modest funding with volunteer professional support to improve global child health.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge the work and

Continent Country ICATCH-Funded Projects

Central America and Caribbean Belize Protecting Smiles for Healthier Futures in Southern Belize Dominican Republic Improving Child Health in the Community

El Salvador Improving Healthcare and International Collaboration Diagnosis and Referral of Undernourished Children

Community Public Health Collaborative in Los Abelines, El Salvador

Guatemala Training the Next Generation of Frontline Health Workers for Child Health in Guatemalaa Haiti Health Care for Haiti’s children

Community Health Worker Outreach to Rural Elementary Schools Programa Hydroxyurea to Treat Sickle Cell Disease in Haitia

Nicaragua Mobile Health Kits for Use in Vulnerable Communities

South America Bolivia Tsimane’ Territory Multi‐Media Public Health Education to Prevent Childhood Illnessa Ecuador Sonrisa’s Children’s Oral Health and Nutrition Project

ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; DOT, directly observed treatment; GOBI FFF, growth monitoring, oral rehydration and diarrhea, breastfeeding, immunization, preventable infectious diseases, family planning/spacing, food supplementation, female education; IMCI, integrated management of childhood illness; INH, isoniazid; TB, tuberculosis.

a In-progress project. TABLE 1 Continued

FIGURE 2

REFERENCES

1. Maru DS, Andrews J, Schwarz D, et al. Crossing the quality chasm in

resource-limited settings. Global Health. 2012;8:41

2. Kerry VB, Mullan F. Global Health Service Partnership: building health professional leadership. Lancet. 2014;383(9929):1688–1691

3. Jilani SM. International child health program marks 10 years, calls for proposals. AAP News, April 28, 2014. Available at: http:// www. aappublications. org/ content/ 35/ 5/ 24. 2. Accessed August 2, 2018

4. Duncan B, Mandalakas AM, Staton DM, Anders B, Behrmann A, Kurbasic M. ICATCH: become a change agent. In:

Berman S, Palfrey JS, Bhutta Z, Grange AO, eds. Global Child Health Advocacy: On the Front Lines. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2013:309–313

5. Hutchins VL, Grason H, Aliza B, Minkovitz C, Guyer B. Community Access to Child Health (CATCH) in the historical context of community pediatrics. Pediatrics. 1999;103(6, pt 3):1373–1383

6. Duncan B, Mandalakas A, Staton D, et al. Child healthcare workers in resource-limited areas improve health with innovative low-cost projects. J Trop Pediatr. 2012;58(2):120–124 ABBREVIATIONS

AAP: American Academy of Pediatrics

ICATCH: International

Community Access to Child Health

LLMIC: low- and low-middle–

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2017-2848 originally published online September 5, 2018;

2018;142;

Pediatrics

Moore, Alcy R. Torres, Manuel Vides and Donna Staton

Ann T. Behrmann, Michael Canarie, Rajesh Dudani, Mirzada Kurbasic, Molly J.

Rachel A. Umoren, Mohamed A. Mohamed, Koye A. Oyerinde, Yvonne E. Vaucher,

Improving Child Health

International Community Access to Child Health Program: 10 Years of

Services

Updated Information &

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/142/4/e20172848

including high resolution figures, can be found at:

References

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/142/4/e20172848#BIBL

This article cites 4 articles, 0 of which you can access for free at:

Subspecialty Collections

alth_sub

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/international_child_he

International Child Health following collection(s):

This article, along with others on similar topics, appears in the

Permissions & Licensing

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/Permissions.xhtml

in its entirety can be found online at:

Information about reproducing this article in parts (figures, tables) or

Reprints

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/reprints.xhtml

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2017-2848 originally published online September 5, 2018;

2018;142;

Pediatrics

Moore, Alcy R. Torres, Manuel Vides and Donna Staton

Ann T. Behrmann, Michael Canarie, Rajesh Dudani, Mirzada Kurbasic, Molly J.

Rachel A. Umoren, Mohamed A. Mohamed, Koye A. Oyerinde, Yvonne E. Vaucher,

Improving Child Health

International Community Access to Child Health Program: 10 Years of

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/142/4/e20172848

located on the World Wide Web at:

The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is

by the American Academy of Pediatrics. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 1073-0397.