The HEADS-ED: A Rapid Mental Health Screening Tool

for Pediatric Patients in the Emergency Department

WHAT’S KNOWN ON THIS SUBJECT: The American Academy of Pediatrics prioritized detection of mental illness in children presenting to emergency departments (ED) by using standardized clinical tools. Only a minority of ED physicians indicate that they use evidence-based screening methods to assess mental health concerns.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS:This study presents the psychometrics of the HEADS ED (home, education, activities/peers, drugs/alcohol, suicidality, emotions/behavior, discharge resources), a brief, standardized screening tool for pediatric EDs. This tool ensures key information is obtained for decision-making, determining acuity level, and areas of need.

abstract

BACKGROUND AND OBJECTIVE:The American Academy of Pediatrics called for action for improved screening of mental health issues in the emergency department (ED). We developed the rapid screening tool home, education, activities/peers, drugs/alcohol, suicidality, emotions/ behavior, discharge resources (HEADS-ED), which is a modification of

“HEADS,”a mnemonic widely used to obtain a psychosocial history in adolescents. The reliability and validity of the tool and its potential for use as a screening measure are presented.

METHODS:ED patients presenting with mental health concerns from March 1 to May 30, 2011 were included. Crisis intervention workers completed the HEADS-ED and the Child and Adolescent Needs and Strengths-Mental Health tool (CANS MH) and patients completed the Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI). Interrater reliability was assessed by using a second HEADS-ED rater for 20% of the sample.

RESULTS:A total of 313 patients were included, mean age was 14.3 (SD 2.63), and there were 182 females (58.1%). Interrater reliability was 0.785 (P,

.001). Correlations were computed for each HEADS-ED category and items from the CANS MH and the CDI. Correlations ranged fromr= 0.17,P,.05 to

r= 0.89, P, .000. The HEADS-ED also predicted psychiatric consult and admission to inpatient psychiatry (sensitivity of 82% and a specificity of 87%; area under the receiver operator characteristic curve of 0.82,P,.01).

CONCLUSIONS:The results provide evidence to support the psychometric properties of the HEADS-ED. The study shows promising results for use in ED decision-making for pediatric patients with mental health concerns.

Pediatrics2012;130:e321–e327 AUTHORS:Mario Cappelli, PhD,a,b,c,dClare Gray, MD,a,e,f

Roger Zemek, MD,d,e,fPaula Cloutier, MA,aAllison Kennedy,

PhD,aElizabeth Glennie, MA,aGuy Doucet, MSW,a,eand John

S. Lyons, PhDa,c

Departments ofaMental Health andeEmergency, Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario, Ottawa, Canada; Departments of bPsychiatry,cPsychology, andfPediatrics, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Canada; anddPediatric Emergency Research Canada (PERC), Ottawa, Canada

KEY WORDS

mental health, emergency department, psychosocial screening

ABBREVIATIONS

ANOVA—analysis of variance

CANS-MH—Child and Adolescent Needs and Strengths-Mental Health tool

CDI—Children’s Depression Inventory CHEO—Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario CIW—crisis intervention worker

ED—emergency department

HEADS-ED—home, education, activities/peers, drugs/alcohol, suicidality, emotions/behavior, discharge resources

ROC—receiver operating characteristic

www.pediatrics.org/cgi/doi/10.1542/peds.2011-3798

doi:10.1542/peds.2011-3798

Accepted for publication Mar 27, 2012

Address correspondence to Mario Cappelli, PhD, Director of Mental Health Research, Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario, Ottawa, ON K1H 8L1 Canada. E-mail: cappelli@cheo.on.ca

PEDIATRICS (ISSN Numbers: Print, 0031-4005; Online, 1098-4275).

Copyright © 2012 by the American Academy of Pediatrics

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE:The authors have indicated they have nofinancial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

FUNDING:Supported by the Academic Health Science Centres Alternate Funding Plan Innovation Fund, the Royal Bank of Canada, and Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario Foundations.

Canada are increasing (15% from 2003 to 2006)1 mirroring increases in EDs

within the United States.2–4The ED has

become a mental health“safety net”5

but is being stretched to its limit.6It is

not surprising that the Committee on Pediatric Emergency Medicine7and the

American Academy of Pediatrics5

iden-tified as a priority the need to better detect mental illness in children pre-senting to the ED by using standardized clinical tools. Similarly, Habis and col-leagues8 found that only a small

mi-nority (9%) of ED physicians indicate that they use evidence-based screening methods to assess mental health con-cerns; a majority of the physicians (62%) identify the lack of an available tool as a significant barrier. Such a tool would need to be brief, easily administered, and help guide clinical decision-making. Currently, there is no standard of prac-tice or tool used to guide the assess-ment and disposition of assess-mental health concerns for pediatric ED patients.2,7,9

Rather than developing a new assess-ment tool, the“HEADS interview” may be able to provide a relevant assessment platform for evaluating pediatric men-tal health problems in the ED. The HEADS is a mnemonic widely used in general medical outpatient settings to obtain a psychosocial history in ado-lescents.10,11It was designed to be used

by physicians as a way to organize the psychosocial history during routine adolescent visits. Although variations exist within the literature describing the HEADS mnemonic (eg, HEADDS, HEEADSSS), there is a commonality throughout. The mnemonic generally stands for key areas such as home, edu-cation, (eating), activities/ambition, drugs and drinking, sexuality, suicide and de-pression, safety.10–15 Its popularity is

twofold; it eases into the more challenging personal questions, and the mnemonic allows it to remain memorable. Finally,

physician training and can be efficiently completed in the ED.

The HEADS was modified to HEADS-ED (freely available on request) as a rapid mental health screening tool to be used in the ED setting. The tool contains 7 items (Home, Education, Activities and peers, Drugs and alcohol, Suicidality, Emotions and behaviors, Discharge resources) with an embedded scoring system with points associated for each variable (0 = no clinical action needed; 1 = needs clinical action but not immediately; and 2 = needs immediate clinical action). The HEADS-ED also includes discharge re-sources, because these resources are often a consideration when discharging someone with moderate mental health issues from the ED. Thus, the HEADS-ED includes the main domains of the HEADS but also expands it briefly to include discharge planning and a guided clin-ical severity/scoring system. Therefore, it provides structure and guides the cli-nician through the assessment/screening process.

The goal of this study is to evaluate the psychometric properties of the tool in-cluding reliability, construct, and criterion-related validity.

METHODS

Setting

Recruitment of patients took place in the ED at the Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario (CHEO), in Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, a tertiary care child-ren’s hospital with an annual ED census of 60 000 children, with∼2200 mental health visits per year. The hospital serves a population of 1 100 300, with 13.1% consisting of visible minorities, and 10.8% considered to be of low in-come.16 Approximately two-thirds of

mental health visits were seen by the crisis intervention workers (CIWs) and the remainder were seen by ED phy-sicians. Patients with mental health

are directly triaged to the CIWs. The CIWs then assess the patients and are able to discharge them from the ED or refer them to the psychiatrist for consultation.

Participants

All children and youth presenting to the ED from March 1, 2011 to May 31, 2011 with a mental health concern seen by a CIW during the ED visit were included in the study. The study was approved by the hospital’s research ethics board.

Measures

The HEADS-ED Tool

This tool was designed by the multi-disciplinary research team to match the

“HEADS”interview as closely as possi-ble while adapting it for ED use and adding a scoring component to assist with decision-making. Each letter stands for a specific component of the patient history. H is for home; E, education; A, activities and peers; D, drugs and alco-hol; E, emotions and behavior; D, dis-charge resources. Three levels of scoring were denoted in this tool: 0, 1, and 2. These levels were developed from the communimetrics theory of measure-ment17 which emphasizes the use of

nonarbitrary levels that translate imme-diately into action. The action levels for the HEADS-ED are designed to be con-sistent with triage decision-making in the ED: no action needed (0); action needed, but not immediately (1); and immediate action required (2). This tool was pur-posely designed to be straightforward and to not require additional training.

Child and Adolescent Needs and Strengths-Mental Health Tool

The Child and Adolescent Needs and Strengths-Mental Health tool (CANS-MH 3.0)18integrates information

challenges. This tool is being used in the CHEO crisis program and is useful for decision-making and communica-tion. The CANS-MH 3.0 is known as a communimetric measure because in-dividual items use anchors that define action levels: (0) no evidence: there is no need for action; (1) watchful waiting/ prevention, this need should be moni-tored, or efforts to prevent it from re-turning or getting worse should be initiated; (2) action: an intervention is required because the need is interfering in some notable way with the individu-al’s, family’s, or community’s function-ing; (3) immediate/intensive action: this need is either dangerous or disabling. Therefore, a score of a 2 or 3 would in-dicate a need for service. The CHEO cri-sis program uses a 23-item version with items key for ED decision-making (pri-marily related to the decision to admit or discharge the patient). The CANS-MH 3.0 has been shown to be reliable at the item level so the reliability of the tool is unaffected by selecting a subset of tar-get items.19 The interrater reliability

between CHEO crisis staff was estab-lished at 0.82 and yearly recertification is required. Interrater reliability by us-ing vignettes across studies averages 0.74, whereas interrater reliability is 0.85 when raters use case records/ current cases.18 The previous version

of the CANS had demonstrated good validity19; it was significantly correlated

(r = 0.63 to r = 0.72) with an in-dependently assessed Child and Ado-lescent Functional Assessment Scale.20

In addition, the total scores on the di-mensions of the tool reliably distin-guished level of care received.21

Children’s Depression Inventory

The Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI)22is a self-report measure of

de-pressive symptoms for youth aged 7 to 17 years. Test-retest reliabilities vary depending on the time interval between assessments. Overall, the CDI demon-strates acceptable levels of stability

(2 weeks, 0.82; 3 weeks, 0.74–0.83). This measure is well validated with good explanatory and predictive value and correlates well to other similar scales administered concurrently.22

Procedure

For each patient triaged directly to the CIW, the CIW documented clinical in-formation by using both the HEADS-ED tool and the CANS-MH 3.0. This process then allowed us to compare the brief HEADS-ED tool with the more compre-hensive CANS-MH 3.0. Furthermore, participants over the age of 7 were asked to complete the CDI. To assess for interrater reliability, a research assis-tant trained and qualified to complete the CANS MH 3.0 reviewed the chart notes for a random set of 20% of the patients and completed the HEADS-ED tool.

Data Analysis

The data were analyzed by using SPSS statistics version 19.0 (SPSS Inc, Chi-cago, IL). Descriptive statistics were obtained by frequency analysis and measures of central tendency.x2 anal-ysis was used to examine the proportion of patients referred for consult or ad-mitted by HEADS-ED item and total scores. To test convergent validity, cor-relations were obtained between HEADS-ED categories and the CANS-MH 3.0. Analyses were performed for correla-tions of both individual and grouped items. For example, the HEADS-ED“home” history may be theoretically related to the CANS-MH 3.0 items: parent-child relational problems, safety, supervision, family functioning, and family strength; these items were correlated individually and as a group. In addition, correlations were obtained between total scaled score of the CDI and Subscaletscore from the CDI to the related items from the HEADS-ED. Cross-tabs were used to establish sensitivity and specificity, and receiver operating characteristic (ROC)

curves were analyzed to determine the predictive accuracy of the tool for screening for admission. Intraclass correlations were used to assess in-terrater reliability.

RESULTS

A total of 378 patients were seen in the crisis intervention program at the CHEO ED from March 1, 2011 to May 29, 2011. The crisis workers completed HEADS-ED and CANS-MH 3.0 tools for 313 patients (83% enrollment), leaving 65 patients without completed documentation. The mean age of the sample was 14.3 years (SD 2.63; range 4–17; median 15) with the majority being female n = 182 (58.1%). Of these patients, 181 (61%) reported seeing a mental health pro-fessional, and 161 (51.4%) were taking medications. No significant differences were found between those that received documentation and those that did not (age,F[13, 378] = 1.644; gender, F [1, 378] = 0.461, allPvalues were..05).

Table 1 presents the frequency distri-bution of each item of the HEADS-ED tool for the sample. As can be seen from the table, the sample of youth is distributed throughout the tool. Those youth who present with suicidality and emotion/behavior concerns are more likely to need immediate action in com-parison with problems with home, edu-cation, activities/peers, and also alcohol and drugs.

Reliability

The overall interrater reliability analysis indicated strong agreement between raters (r= 0.785). Interrater reliability is preferred, since internal consistency is not relevant for communimetric meas-ures because individual items measure different aspects of levels of action and the items are not chosen to necessarily correlate with one another.17 Table 2

presents the results of the single-item reliability that ranges from good 0.57 to excellent 0.90.23

Concurrent Validity

Concurrent validity was assessed by examining the relationship between the HEADS-ED, CDI, and CANS-MH 3.0. Tables 3 and 4 present the correlation between the measures. Because the HEADS-ED captures a broad range of items from the CANS-MH 3.0, we first combined those CANS-MH 3.0 items theoretically related to the individual HEADS-ED items (ie, combined CANS items school ac-hievement and attendance scores) and compared them with the corresponding HEADS-ED item (ie, education). As can be seen in Table 3, the HEADS-ED items were significantly correlated with correspon-ding CANS scores.

In Table 4, the correlations between the HEADS-ED and CDI are presented. The HEADS-ED items of suicidality, activity/ peers, and emotion/behavior were sig-nificantly correlated with the total CDI scaled score and subscales t score. The HEADS-ED suicidality item was also correlated with the youth’s report on the single CDI item (item 9 on the CDI) directly questioning the patient about their suicidal intentions (r= 0.57,

P,.05).

Predictive Validity

We examined the predictive validity of the HEADS-ED by determining how well the tool predicted consultation for a full psychiatric assessment and sub-sequent admission to inpatient care. Table 5 presents the frequencies of the 7 items of the HEADS-ED broken down by the need for action (0, 1, 2) for each of the items. Of the total group of 313 youth, nearly half (47.8%) required a full psychiatric assessment, and 21.1% of these youth were ultimately admitted to inpatient care.x2analyses were then conducted on each of the items to

examine whether there was a differ-ence in the level of need for action and consultation and admission. With the exception of x2 examining home envi-ronment and admission, significantx2 analyses were obtained on all the remaining items for both requests for consultation and admission to hospital.

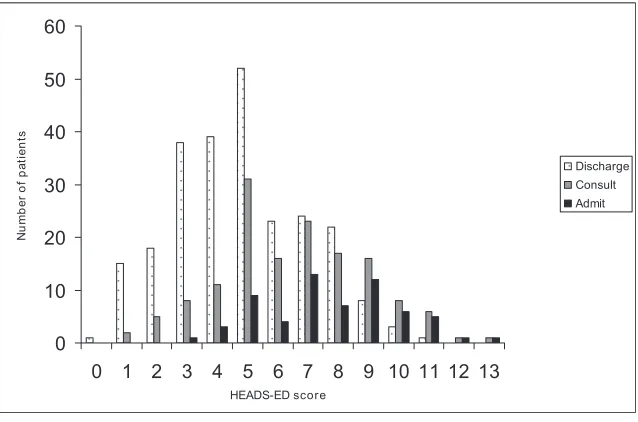

The 7 items were then combined to create a total HEADS-ED score (mean 5.4 [SD 2.5], 25th percentile = 4, 50th per-centile = 5, 75th perper-centile = 7). The frequency distribution of the total scores broken down by those who were referred for psychiatric consult and those who were discharged from the ED is illustrated in Fig 1. It is not surprising that, as the total score of the HEADS-ED increases, the proportion of youth who obtain a full psychiatric assessment and admitted to hospital also increa-ses. We then performed an analysis of variance (ANOVA) to determine whether there was a mean difference in scores for those referred for psychiatric con-sult. The ANOVA was significant F (1304) = 66.19,P,.000. The mean score for those that received a consult was 6.5 (SD = 2.4) and those that did not was 4.4 (SD = 2.1). A second ANOVA was performed to de-termine whether there was a mean dif-ference in scores for those admitted and those discharged. This also was signifi -cantF (1, 305) = 86.56,P, .000. The mean score for those admitted was 7.73

Needed,n(%) Not Immediately,n(%) Action,n(%)

H ome 142 (45.4) 144 (46.0) 27 (8.0)

E ducation 124 (39.6) 149 (47.6) 39 (12.5)

A ctivities and peers 164 (52.7) 116 (37.3) 31 (10.0)

D rugs and alcohol 216 (69.5) 52 (16.7) 43 (13.8)

S uicidality 68 (21.7) 167 (53.4) 78 (24.9)

E motions and behaviors 39 (12.5) 198 (63.3) 76 (24.3)

D ischarge resources 94 (30.3) 148 (47.7) 68 (21.9)

TABLE 2 Comparison of CIWs and Independent Research Assistant Across Items of the HEADS-ED

Intraclass Correlations

H ome 0.776

E ducation 0.775

A ctivities and peers 0.722

D rugs and alcohol 0.901

S uicidality 0.838

E motions and behaviors 0.568

D ischarge resources 0.619

AllPvalues are,.001.

TABLE 3 Correlation Table of the HEADS-ED With the Corresponding Items From the CANS-MH 3.0

r

Home: family functioning, family strengths, supervision, safety, and parent-child relational problems scores

0.67**

Education: school achievement and school attendance scores 0.69**

Activities and peers: peer functioning, interpersonal strengths, community involvement, talents/interests, and school attendance

0.18**

Drugs and alcohola 0.89**

Suicidalitya 0.76**

Emotions and behavior:anxiety, mood, attention/impulse control, oppositional behavior, conduct behavior, emotional control

0.32**

Discharge resources: there were no corresponding CANS-MH 3.0 variables for this item.

aThere is only 1 CANS-MH item.

**P,.01.

r

Activities and peers

CDI total of peer and activity related variables (Q 4, 12, 20, 21, 22)

0.36**

Suicidality

Totaltscore 0.34**

Subscale: negative mood 0.36**

Subscale: negative self-esteem 0.43** Emotions and behavior

CDI total 0.18*

Subscale: negative mood 0.19*

Subscale: ineffectiveness 0.17*

Subscale: anhedonia 0.20*

(SD = 2.22;n= 62) and those discharged was 4.82 (SD = 2.19;n= 244).

Predictive Accuracy

Based on the analysis from the above ANOVA, we sought to determine if the use of a cutoff score of.7 would be useful to predict admission to hospital or dis-charge to the community. The use of cross-tab procedure results indicated a sensitivity of 48.5 and a specificity of 87.5. Although the specificity was high, the sensitivity was not adequate and would result in an inordinate number of youth being recommended for hospitalization. After expert review, we revised the de-cision model regarding hospitalization to suggest admission would not occur without significant levels of suicidal risk. Therefore, we set an algorithm of total HEADS-ED score of.7 and a suicidal risk

factor of 2. Again, use of the cross-tab procedure results now indicated sensi-tivity of 81.8 and a specificity of 87.

Furthermore, to analyze the predictive validity of the HEADS-ED screening tool for admission decisions we analyzed the tool by using the ROC curve pro-cedure.24 Results indicated a signifi

-cant result with area under the ROC curve of 0.817,P,.01.

DISCUSSION

The inclusion of a standardized asses-sment tool in the ED to screen for mental health problems has been advocated by both the American Academy of Pediat-rics and the Committee of Pediatric Emergency Medicine.5,25 The HEADS-ED

is a rapid mental health screening tool that appears to have the potential to identify level of crisis in children in the

ED setting. The result of this current study provides evidence of criterion, concurrent, predictive validity and inter-rater reliability.

The HEADS-ED is correlated with the youth’s ratings of depression and a more comprehensive clinician rating of mental health strengths and needs. Perhaps more importantly, the study also supports the predictive validity of the tool. The total score from the HEADS-ED indicated statistically and meaning-fully different mean scores for those that were referred for a full psychiatric consultation (above the 50th percentile) and for those that were admitted (above the 75th percentile) to an inpatient psychiatric unit. The result of the ROC procedure also supports the validity of the tool for identifying the level of acuity of mental illness in children. The area under the curve indicates strong sup-port,24demonstrating that the tool had

good detection of indicators of admis-sion to inpatient psychiatry.

The HEADS-ED is thefirst measure to have been developed to date specifically for the ED pediatric mental health pop-ulation. Other tools exist to assess self-harm risk in the ED,26 and there are

still others designed to assess the mul-tidimensional aspects of a crisis pre-sentation and evaluate the patients’ risk,27 including the risk assessment

matrix,28,29 which is probably one of

the better known tools, although it was developed for adults. However, none of these tools have been successfully in-corporated within the ED, and we sus-pect this is probably due to the extensive training and the lengthy administration time that is required.

The HEADS-ED has the advantage that,

first, it uses the HEADS11 mnemonic

which is familiar to many physicians and often taught in medical school. It is assumed that emergency phy-sician and health clinicians already possess the skills to inquire about the items (eg, home environment) or level

TABLE 5 Proportion of Patients Referred for Psychiatric Consult and Admitted by Level of HEADS-ED

Score Total Sample, 313 (100),n(%)

Consult, 149 (47.8),n(%)

Admitted, 66 (21.1),n(%)

Home * NS

Supportive 0 142 (45.4) 64 (45.4) 34 (23.9)

Conflicts 1 144 (46.0) 66 (45.8) 24 (16.7)

Chaotic/dysfunctional 2 27 (8.6) 19 (70.4) 8 (29.6)

Education ** **

On track 0 124 (39.7) 40 (32.3) 13 (10.5)

Grades dropping 1 149 (47.8) 85 (57.4) 40 (26.8)

Failing/not attending school 2 39 (12.5) 23 (59.0) 12 (30.8)

Activities and peers ** **

No change 0 164 (52.7) 53 (32.3) 11 (6.7)

Reduced 1 116 (37.3) 74 (63.8) 37 (31.9)

Withdrawn 2 31 (10.0) 22 (73.3) 18 (58.1)

Drugs and alcohol * *

No or infrequent 0 216 (69.5) 93 (43.3) 36 (16.7)

Occasional 1 52 (16.7) 27 (51.9) 14 (26.9)

Frequent /daily 2 43 (13.8) 28 (65.1) 15 (34.9)

Suicidality ** **

No thoughts 0 68 (21.7) 15 (22.1) 2 (2.9)

Ideation 1 167 (53.4) 67 (40.1) 15 (9.0)

Plan or gesture 2 78 (24.9) 67 (87.0) 49 (62.8)

Emotions and behavior ** **

Mildly anxious/sad/acting out 0 39 (12.5) 6 (15.4) 2 (5.1)

Moderately anxious/sad/acting out 1 198 (63.3) 88 (44.7) 27 (13.6) Significantly distressed/unable to

function/out of control

2 76 (24.3) 55 (72.4) 37 (48.7)

Discharge resources NS NS

Ongoing/well connected 0 94 (30.3) 48 (51.1) 18 (17.0)

Some/not meeting needs 1 148 (47.7) 66 (44.6) 28 (18.9)

None/on wait list 2 68 (21.9) 32 (47.8) 19 (27.9)

NS, nonsignificant. *P,.05; **P,.01.

of need (supportive, conflictual, chaotic/ dysfunctional) without needing an ex-tensive“instruction manual”or super-vised training. The items are clinically intuitive, and therefore do not require further training. These are the types of clinical queries that an ED physician would normally conduct as part of diagnostic assessment. The HEADS-ED is easy to administer, does not require scoring, but, as shown in this article, it has both clinical validity and utility. The tools help guide the mental health assessment as well as provide direc-tion for follow-up services, for exam-ple, if the home environment is chaotic,

then recommendation for family ther-apy or parent training can be sug-gested. Mental health services that are available within the hospital and community can easily be linked to each of the items allowing ED physi-cians to be even more specific in their recommendations (eg, a local com-munity program that offers addic-tion services for youth). Our center is currently developing a web-based ad-ministration of the HEADS-ED linked electronically to hospital and community services.

The limitations of the current study, including the relatively small sample

and future validation studies. ED phy-sician ratings on the HEADS-ED will be compared with mental health specialist ratings and youth/parent reports of behavioral and emotional functioning. The HEADS-ED will also need to be ev-aluated in a multisite, pediatric and nonpediatric tertiary center study to increase the sample size and general-izability of the findings. We are opti-mistic that, given our currentfindings and the evidence in general on the HEADS,10,11 future results will provide

further support of the HEADS-ED.

CONCLUSIONS

The HEADS-ED shows promise as a brief, easily administered standardized screen-ing tool useful in directscreen-ing the interview process to ensure that key information is obtained for decision-making, un-covering the level of crisis, and deter-mining the level of treatment needed. It provides potential for use as a deci-sional tool to determine referral for psychiatric consultation, admission de-cisions, and guidance in the selection of services for patients discharged back to the community.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank the CHEO crisis intervention team for their significant contribution to this project.

REFERENCES

1. Newton AS, Ali S, Johnson DW, et al. A 4-year review of pediatric mental health

emergen-cies in Alberta.CJEM. 2009;11(5):447–454

2. Sills MR, Bland SD. Summary statistics for pediatric psychiatric visits to US emergency

departments.Pediatrics. 2002;110(4).

Avail-able at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/ 110/4/e40

3. Mahajan P, Alpern ER, Grupp-Phelan J, et al;

Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Re-search Network (PECARN). Epidemiology

of psychiatric-related visits to emergency

departments in a multicenter collaborative

research pediatric network.Pediatr Emerg

Care. 2009;25(11):715–720

4. Grupp-Phelan J, Harman JS, Kelleher KJ. Trends in mental health and chronic condition visits by children presenting for care at

U.S. emergency departments.Public Health

Rep. 2007;122(1):55–61

5. American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee

on Pediatric Emergency Medicine; American College of Emergency Physicians and

Pedi-atric Emergency Medicine Committee, Dolan

MA, Mace SE. Pediatric mental health emergencies in the emergency medical

services system. Pediatrics. 2006;118(4):

1764–1767

6. Fernandes CM, Tanabe P, Gilboy N, et al. Five-level triage: a report from the ACEP/

ENA five-level triage task force. J Emerg

Nurs. 2005;31(1):39–50, quiz 118

7. Dolan MA, Fein JA; Committee on

Pediat-ric Emergency Medicine. PediatPediat-ric and adolescent mental health emergencies in

the emergency medical services system.

0 10 20 30 40 50

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13

HEADS-ED score

Nu

m

b

e

r

of

pa

tie

nt

s

Discharge

Consult

Admit

FIGURE 1

Pediatrics. 2011;127(5). Available at: www. pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/127/5/e1356

8. Habis A, Tall L, Smith J, Guenther E. Pediatric

emergency medicine physicians’current

practices and beliefs regarding mental

health screening.Pediatr Emerg Care. 2007;

23(6):387–393

9. Kennedy A, Cloutier P, Glennie JE, Gray C. Establishing best practice in pediatric emergency mental health: a prospective study examining clinical characteristics. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2009;25(6):380–386

10. Goldenring J, Cohen E. Getting into

adoles-cent heads.Contemp Pediatr. 1988;5(7):75

11. Goldenring J, Rosen D. Getting into

adoles-cent heads: an essential update. Contemp

Pediatr. 2004;21(1):64–90

12. Copperman SM. HEADS helps doctors elicit honest answers to delicate teen questions. AAP News. 1999;15(1):18

13. Montalto NJ. Implementing the guidelines

for adolescent preventive services.Am Fam

Physician. 1998;57(9):2181–2190

14. Reitman D.“HEADDS”up on talking with

teen-agers. Pediatrics Consultant Live. 2007;6(9).

Available at: www.pediatricsconsultantlive. com/display/article/1803329/11894#. Accessed April 23, 2012

15. Walling A. Clinical information from the

in-ternational family literature.Family Practice

Int. 1999;59(11):3250. Available at: www.aafp.

org/afp/1999/0601/p3250.html?printable=afp. Accessed March 20, 2012

16. Dall K, Lefebvre M, Pacey M, Sahai V. Cham-plain LHIN: socio-economic indicators atlas. Ottawa, ON, Canada: Government of Ontario; 2006:26. Available at: www.champlainlhin.on. ca/lhinresearch.aspx?kmensel=e2f22c9a_ 72_206_132_4. Accessed April 23, 2012

17. Lyons JS.Communimetrics. New York, NY:

Springer; 2009

18. Lyons JS, Bisnaire L, Greenham S, Dods J. The child and adolescent needs and strengths (CAN MH 3.0 manual). 2006. Available at: http://www.praedfoundation.org. Accessed April 23 2012

19. Anderson RL, Lyons JS, Giles DM, Price JA, Estes G. Examining the reliability of the child and adolescent needs and strengths-mental health (CANS-MH) scale from two per-spectives: a comparison of clinician and

research ratings.J Child Fam Stud. 2003;

12(3):279–289

20. Hodges K, Wotring J. Client typology based on functioning across domains using the CAFAS: implications for service planning. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2000;27(3):257– 270

21. Lyons JS. Redressing the Emperor:

Im-proving Our Children’s Public Mental Health

System. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publish-ing Group; 2004

22. Kovacs M. Manual for the Children’s

De-pression Inventory. North Tonawanda, NJ: Multi-Health Systems; 1992

23. Shrout PE, Fleiss JL. Intraclass correlations:

uses in assessing rater reliability.Psychol

Bull. 1979;86(2):420–428

24. Bewick V, Cheek L, Ball J. Statistics review 13: receiver operating characteristic curves. Crit Care. 2004;8(6):508–512

25. Dolan MA, Mace SE; American Academy of Pediatrics; ; American College of Emergency Physicians. Pediatric mental health emer-gencies in the emergency medical services

system.Ann Emerg Med. 2006;48(4):484–486

26. Randall JR, Colman I, Rowe BH. A systematic review of psychometric assessment of self-harm risk in the emergency department. J Affect Disord. 2011;134(1-3):348–355

27. Lewis S, Roberts AR. Crisis assessment tools: the good, the bad, and the available. Brief Treat Crisis Interv. 2001;1(1):17–28

28. Patel AS, Harrison A, Bruce-Jones W. Evaluation of the risk assessment matrix: a mental health

triage tool.Emerg Med J. 2009;26(1):11–14

29. Hart C, Colley R, Harrison A. Using a risk assessment matrix with mental health

patients in emergency departments.Emerg

Nurse. 2005;12(9):21–28

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2011-3798 originally published online July 23, 2012;

2012;130;e321

Pediatrics

Elizabeth Glennie, Guy Doucet and John S. Lyons

Mario Cappelli, Clare Gray, Roger Zemek, Paula Cloutier, Allison Kennedy,

Services

Updated Information &

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/130/2/e321

including high resolution figures, can be found at:

References

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/130/2/e321#BIBL

This article cites 23 articles, 2 of which you can access for free at:

Subspecialty Collections

sub

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/emergency_medicine_

Emergency Medicine following collection(s):

This article, along with others on similar topics, appears in the

Permissions & Licensing

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/Permissions.xhtml

in its entirety can be found online at:

Information about reproducing this article in parts (figures, tables) or

Reprints

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/reprints.xhtml

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2011-3798 originally published online July 23, 2012;

2012;130;e321

Pediatrics

Elizabeth Glennie, Guy Doucet and John S. Lyons

Mario Cappelli, Clare Gray, Roger Zemek, Paula Cloutier, Allison Kennedy,

in the Emergency Department

The HEADS-ED: A Rapid Mental Health Screening Tool for Pediatric Patients

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/130/2/e321

located on the World Wide Web at:

The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is

by the American Academy of Pediatrics. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 1073-0397.