Bowel Preparations for Colonoscopy: An RCT

WHAT’S KNOWN ON THIS SUBJECT: Available bowel preparation solutions for colonoscopy continue to represent a challenge for children and their families due to poor taste, high volume, and dietary restrictions with subsequent poor compliance and need to place nasogastric tube for administration.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS: Low-volume polyethylene glycol (PEG) preparations and sodium picosulphate plus magnesium oxide and citric acid (NaPico+MgCit) are noninferior to PEG 4000 with simethicon for bowel preparation before colonoscopy in children. Given its higher tolerability and acceptability profile, NaPico+MgCit should be preferred in children.

abstract

BACKGROUND:The ideal preparation regimen for pediatric colonoscopy remains elusive, and available preparations continue to represent a chal-lenge for children. The aim of this study was to compare the efficacy, safety, tolerability, and acceptance of 4 methods of bowel cleansing before colonoscopy in children.

METHODS: This randomized, investigator-blinded, noninferiority trial enrolled all children aged 2 to 18 years undergoing elective colonoscopy in a referral center for pediatric gastroenterology. Patients were randomly assigned to receive polyethylene glycol (PEG) 4000 with simethicon ELS group) or PEG-4000 with citrates and simethicone plus bisacodyl (PEG-CS+Bisacodyl group), or PEG 3350 with ascorbic acid (PEG-Asc group), or sodium picosulfate plus magnesium oxide and citric acid (NaPico+MgCit group). Bowel cleansing was evaluated according to the Boston Bowel Preparation Scale. The primary end point was overall colon cleansing. Tolerability, acceptability, and compliance were also evaluated.

RESULTS:Two hundred ninety-nine patients were randomly allocated to the 4 groups. In the per-protocol analysis, PEG-CS+Bisacodyl, PEG-Asc, and NaPico+MgCit were noninferior to PEG-ELS in bowel-cleansing efficacy of both the whole colon (P= .910) and colonic segments. No serious adverse events occurred in any group. Rates of tolerability, acceptability, and compliance were significantly higher in the NaPico+MgCit group.

CONCLUSIONS:Low-volume PEG preparations (PEG-CS+Bisacodyl, PEG-Asc) and NaPico+MgCit are noninferior to PEG-ELS in children, representing an attractive alternative to high-volume regimens in clinical practice. Because of the higher tolerability and acceptability profile, NaPico+MgCit would appear as the most suitable regimen for bowel preparation in children.

Pediatrics2014;134:249–256

AUTHORS:Giovanni Di Nardo, MD, PhD,aMarina Aloi, MD,

PhD,aSalvatore Cucchiara, MD, PhD,aCristiano Spada,

MD,bCesare Hassan, MD,bFortunata Civitelli, MD,a

Federica Nuti, MD, PhD,aChiara Ziparo, MD,aAndrea

Pession, MD, PhD,cMario Lima, MD, PhD,dGiuseppe La

Torre, MD, PhD,eand Salvatore Oliva, MDa

Departments ofaPediatrics, Pediatric Gastroenterology Unit, and ePublic Health and Infectious Diseases,“Sapienza”University of

Rome, Rome, Italy;bDigestive Endoscopy Unit, Università Cattolica

del Sacro Cuore, Rome, Italy; and Departments ofcPaediatrics, Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition Unit, anddPediatric

Surgery, S. Orsola-Malpighi Hospital, University of Bologna, Bologna, Italy

KEY WORDS

colonoscopy, colon cleansing, children

ABBREVIATIONS

BBPS—Boston Bowel Preparation scale CI—confidence interval

NaPico+MgCit—sodium picosulphate plus magnesium oxide and citric acid

PEG—polyethylene glycol

PEG-Asc—polyethylene glycol 3350 with ascorbic acid PEG-CS—polyethylene glycol 4000 with citrates PEG-ELS—polyethylene glycol 4000 with simethicon

Drs Di Nardo and Oliva conceptualized and designed the study, performed endoscopy, drafted the initial manuscript; Drs Aloi, Civitelli, Nuti, and Ziparo conceptualized and designed the study and enrolled and followed-up patients; Drs Hassan, Spada, Pession, and Lima conceptualized and designed the study and contributed significantly to thefinal revision of the manuscript; Dr La Torre carried out the statistical analyses and reviewed and revised the manuscript; Dr Cucchiara is the head of the Pediatric Gastroenterology Unit, performed endoscopy and reviewed and revised the manuscript; and all authors approved thefinal manuscript as submitted.

This trial has been registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov (identifier NCT01711437).

www.pediatrics.org/cgi/doi/10.1542/peds.2014-0131

doi:10.1542/peds.2014-0131

Accepted for publication May 1, 2014

Address correspondence to Giovanni Di Nardo, Department of Pediatrics, Pediatric Gastroenterology and Liver Unit,“Sapienza” University of Rome, University Hospital Umberto I, Viale Regina Elena 324-00161 Rome, Italy. E-mail: giovanni.dinardo@uniroma1.it

PEDIATRICS (ISSN Numbers: Print, 0031-4005; Online, 1098-4275).

Copyright © 2014 by the American Academy of Pediatrics

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE:The authors have indicated they have nofinancial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

FUNDING:No external funding.

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST:The authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

trointestinal tract conditions affecting children and adolescents. For example, it is crucial for establishing the diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease and pro-vides definitive therapeutic options in patients with colonic polyps or lower gastrointestinal bleeding.1The success of colonoscopy relies on multiple factors, and bowel preparation is among the most important of these. Inadequate bowel cleansing may have negative con-sequences for the examination, including incomplete visualization of the colon, missed detection of lesions, lower pro-cedural safety, prolonged procedure time, and reduced interval time for follow-up with significant economic im-pact.2Up to 20% to 30% of incomplete colonoscopies are due to inadequate bowel cleansing, often attributed to the significant discomfort associated with the various preparation regimens.3–5

The ideal preparation should be of low volume, palatable, and successful in complete colon cleansing. Additionally, it should not be associated with adverse events including no significantfluid or electrolyte abnormalities or effects on histologyfindings. Despite the availability of various bowel preparations, the ideal preparation regimen for pediatric colo-noscopy remains elusive, and only few well-controlled studies in pediatric pop-ulation have been published.6,7Available preparations continue to represent a challenge for children and their fami-lies because of poor taste, large volume, and dietary restrictions with subsequent poor compliance and need to place na-sogastric tube for the administration of intestinal lavage solution.6

The primary aim of this investigator-blinded, randomized, controlled trial was to compare the efficacy of four methods of bowel cleansing before colonoscopy in children. Secondary aims were to com-pare safety, tolerability and acceptance of these four bowel cleansing solutions.

Study Design

This is a single center, randomized, observer-blind, parallel group study conducted in Italy. The study design was defined according to the interna-tional recognized guidelines for clinical studies (www.clinicaltrials.gov,

Identi-fier NCT01711437) and was approved by the local ethics committee. Written assent from young patients and in-formed consent from the legal guard-ian and patients aged.14 years were obtained.

Participants

Eligible participants were all children aged 2 to 18 years undergoing elective colonos-copy in our institution. Exclusion criteria were (1) requirement for urgent colonos-copy, (2) bowel obstruction, (3) known or suspected hypersensitivity to the active or other ingredients, (4) clinically significant electrolyte imbalance, (5) previous in-testinal resection, and (6) known meta-bolic, renal, or cardiac disease.

The study took place in the Pediatric Gastroenterology Unit of the University of Rome, Sapienza in Rome, Italy, from January 2011 to February 2013. This unit is an academic tertiary referral center for pediatric IBD and for gastrointesti-nal endoscopy.

Interventions

Group A patients received a polyethylene glycol 4000 (PEG) solution with simethicon (PEG-ELS; Selg Esse, Promefarm, Italy) starting at 4PMthe day before

colonos-copy at a dose of 100 mL/Kg (maximum 4 L). The patients were instructed to drink all the solution in∼4 to 6 hours.

Group B patients received a combination of PEG 4000 with citrates and bisacodyl (PEG-CS+Bisacodyl). PEG-CS is a new sulfate-free iso-osmotic formulation of PEG 4000 with citrates and simethicone (Lovol-esse; Promefarm, Milan, Italy) available as powder to be dissolved in 2 L of water.

on the weight and on the constipation questionnaire) bisacodyl 5-mg tablets (Lovoldyl; Promefarm, Milan, Italy) at 4PM,

followed 2 to 3 hours later by 50 mL/kg (maximum 2 L) of PEG-CS solution. Pa-tients were instructed to drink all the solution in∼2 to 3 hours.

Stool appearance was assessed by the children and their parents with the Bristol stool form chart.8Stool type 1 or 2 was considered consistent with con-stipation.

Because bisacodyl could not be adminis-tered in a crushed tablet form per manu-facturer’s recommendations, we decided to use the following dosage: 1 tablet in children #20 kg, 2 tablets for children between 20 and 30 kg, and 3 tablets for children $30 kg. In children with con-stipation, dosages were increased as fol-lows: 2 tablets in children#20 kg, 3 tablets in children between 20 and 30 kg, and 3 tablets in children$30 kg, respectively.

Group C patients received a PEG 3350 hyperosmotic solution with ascorbic acid (PEG-Asc; Moviprep, Norgine Ltd, Harefield, United Kingdom) starting at 4PMthe day

before the colonoscopy at a dose of 50 mL/kg (maximum 2 L) with 25 mL/kg ad-ditional clearfluid (maximum 1 L) after completing solution intake according to the instruction of the manufacturing company. The patients were instructed to drink all the solution in∼2 to 3 hours.

Group D patients received 2 oral doses of sodium picosulfate plus magnesium oxide and citric acid (NaPico+MgCit; Picoprep, Ferring Italia, Milan, Italy), each diluted in 150 mL of water, at 4PMand 5 hours later

company. No solid food intake was allowed during the 24 hours before the examination according to the instructions of the manufacturing company.

In all 4 groups, a nasogastric tube was inserted if the child failed to drink the prescribed amount of cleanout prepa-ration within thefirst hour.

The preparations were dispensed by a nurse who carefully explained how the products should be taken, emphasizing the importance of complete intake of the solution to ensure a safe and effective procedure. Moreover, each patient was provided with dietary instructions: low residue diet for 3 days before colonos-copy. During and after bowel preparation, solid food was not allowed. Clear liquid could be taken until 2 hours before the procedure. All patients enrolled in this study were scheduled for colonoscopy before 11AMto avoid a large variability in

the interval between bowel preparation and colonoscopy.

Evaluation of Bowel Preparations

Efficacy

Preparation efficacy was evaluated by the blinded endoscopist according to the Boston Bowel Preparation Scale (BBPS)9 consisting of a 4-point scoring system applied to each of the 3 broad regions of the colon: right colon, transverse colon, and left colon (see Table 1 for details). In addition, overall cleansing of the colon was scored by summing up the scores of each segment. For the study, the total score ranging from 0 to 9 was divided into 4 classes: excellent cleansing (total score 8–9), good cleansing (total score 6–7), poor cleansing (total score 4–5), and in-adequate cleansing (total score 0–3). For the primary efficacy variable, excellent and good cleansing were considered

“successful” and poor or inadequate as

“failure.” Before study initiation, the 3 endoscopists (GDN, SO, and SC) per-formed a calibration exercise on 20 colo-noscopies using the scoring system adopted in this study (BBPS) to reach

a satisfactory level of concordance among the physicians involved in the assessment of the degree of bowel cleansing.

All examinations were performed with a pediatric colonoscope (EVIS EXERA II video colonoscope PCF-Q180I, Olympus, Hamburg, Germany) under general anesthesia (in patients ,10 years of age, undergoing both upper and lower endoscopy or with poor clinical con-ditions) or with moderate intravenous sedation (ie, midazolam 0.1 mg/kg in-travenous, maximum dosage 5 mg).

Safety

Vital signs, complete physical examina-tion, and blood tests were performed at the time of patient enrollment and on the day of colonoscopy and included liver and kidney function test, potassium, magne-sium, sodium, chlorides, and calcium. Adverse events were assessed on the day of colonoscopy by direct questioning and telephone interview 48 to 96 hours after colonoscopy. All new symptoms were considered to be treatment related and are included in the analysis. Any symptom that manifested after treatment (except those expected and included in the evaluation of gastrointestinal tolerability) and exacerbations of preexisting symp-toms were assumed to be related to the bowel preparation regimen.

Tolerability, Acceptability, and Compliance

On the morning of colonoscopy, imme-diately before the procedure, a nurse questioned each patient about his or

her experience by using a standardized questionnaire. Patients were asked about tolerability, need for nasogastric tube placement, acceptability, and com-pliance. The endoscopist was not al-lowed to take part in the questioning or to supervise the questionnaire before colonoscopy.

Tolerability assessment was based on the recording of occurrence and severity of gastrointestinal symptoms such as nau-sea, bloating, abdominal, pain/cramps, and anal discomfort. A 5-point scale (1 = severely distressing, 2 = distressing, 3 = bothersome, 4 = mild, and 5 = none) was used to score the tolerability.10The need for nasogastric tube insertion was also assessed.

The easiness of taking or swallowing the solution was graded according to the following scale: very severe distress = 4, severe distress = 3, moderate distress = 2, mild distress = 1, no distress = 0.

Willingness to repeat the same type of bowel preparation if necessary was also evaluated.

Compliance was scored on a 3-point scale according to the percentage of solution consumed (excellent: intake of the whole solution; good: intake of at least 75% of the solution; poor: intake of,75%).

Study End Points

The primary efficacy end point was the overall colon cleansing defined as the rate of “successful” cleansing (excel-lent and good scores in the BBPS, ie,

$6 points).

TABLE 1 Boston Bowel Preparation Scale

Gradea Findings

0 Unprepared colon segment with mucosa not seen due to solid stool that cannot be cleared. 1 Portion of mucosa of the colon segment seen, but other areas of the colon segment not well seen

due to staining, residual stool, and/or opaque liquid.

2 Minor amount of residual staining, small fragments of stool, and/or opaque liquid, but mucosa of colon segment seen well.

3 Entire mucosa of colon segment seen well with no residual staining, small fragments of stool, or opaque liquid.

aApplied to each of the 3 broad regions of the colon: right colon (including the cecum and ascending colon), transverse colon

(including the hepatic and splenicflexures), and left colon (including descending colon, sigmoid colon, and rectum). Total BBPS score ranges from 0 to 9.

specific symptoms associated to colonic lavage solutions, (3) the rate of children who declared that the intake of the so-lution was easy, (4) the rate of children who declared that they would be willing to repeat the same preparation regimen if needed, and (5) the rate of children taking an amount of solution$75%.

Randomization and Blinding

A randomized computer-generated list in blocksof6waspreparedbyabiostatistician, and eligible children were allocated to re-ceive1ofthe4bowelpreparations,stratified by 3 age groups: 2 to 7 years, 8 to 13 years, and 14 to 18 years. Opaque, sealed, and signed envelopes were prepared and numbered to ensure sequential allocation. Treatment was assigned by a clinic nurse using the next numbered envelope, opened only after written consent was obtained. The cleanout regimen was dispensed directly to the family.

The study was observer blind: the endo-scopists were not allowed to perform any activities associated with study prepa-ration before and after colonoscopy and had to avoid any discussion with the patients and the staff, which could dis-close the type of bowel preparation.

Statistical Analysis

The samples size was calculated with the assumption of noninferiority between high-volume and low-volume regimen.

Ef-ficacy rate of high-volume regimens was assumed to be 80%.11 In addition, a dif-ference of$20% of efficacy (ie, rate of successful bowel cleansing) between the high-volume and each of the low-volume regimens was assumed to be clinically relevant. To maintain the hypothesis, 5% type I error (a), and 80% power (= 1–b), the required sample size was estimated to be 70 patients per each arm.

The statistical analysis was performed by using absolute and relative frequency tables and contingency tables. The

uni-dent’s test for continuous ones. Differ-ences in pre–post laboratory variables for each group were assessed using the Wil-coxon signed-ranks test. Both intention-to-treat and per protocol analysis were provided. The noninferiority study was limited to the primary end point, whereas for tolerability, safety, and acceptance, superiority of the new treatment over the reference standard was analyzed. Be-cause of the lack of data on the possible improvement in tolerability and accep-tance in both adult and pediatric pop-ulations, it was necessary to base our sample size evaluation only in the primary end point.

The statistical significance was set at P,.05. The analysis was conducted by using SPSS, version 19.0.

RESULTS

Figure 1 shows the patients studyflow. Of the 299 randomized patients 11 were ex-cluded from the per protocol analysis (colonoscopy not performed in 8, ran-domized despite not meeting eligibility criteria 1, insufficient compliance 2). The 8 patients did not perform colonoscopy for reasons related to the hospital organiza-tion of the clinical activity and not related to the doctor choice or to patient refusal of the bowel solution. Two patients were excluded from the analysis because they added to the prescribed preparation a PEG-based laxative in the week before colonoscopy as commonly used in our institution before the study.

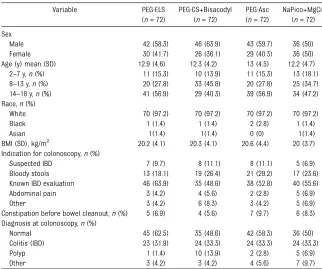

The baseline and clinical character-istics of patients were similar for the 2 groups and are reported in Table 2.

Efficacy of Bowel Cleansing No difference was found between the 4 groups in any of the parameters used to evaluate the efficacy of bowel cleansing (Table 3).

A successful cleansing level (excellent and good scores in the BBPS, ie $6

fi –

PEG-ELS, in 87.5% of PEG-CS+Bisacodyl (95% CI: 78.3–93.7), in 83.3% (95% CI: 73.4–90.6) of PEG-Asc, and in 90.3% (95% CI: 81.7–95.6) of NaPico+MgCit patients in the per protocol analysis (P= .910).

The results were similar at intention-to-treat analysis (88% vs 85.1% vs 78.9% vs 87.8%;P= .366). Details on the degrees of level of preparation according to BBPS scale are provided in Table 3.

Bowel cleansing was also evaluated by colonic segment. As showed in Table 3, no statistical significant difference in the efficacy of the 4 bowel-cleansing solutions was found in the different colonic segments.

Low-volume solutions (PEG-CS+Bisacodyl, PEG-Asc) and NaPico+MgCit were non-inferior to standard high-volume solution (PEG-ELS) in the bowel-cleansing efficacy of the different colonic segment and of the whole colon.

Cecal intubation rate and the time re-quired to reach the cecum were similar in the study groups (Table 3).

Safety and Tolerability

There was no difference in the incidence of dehydration between the 4 study arms, as judged by vital signs and clinical need for intravenousfluids.

Only 1 clinical adverse event occurred in a 10-year-old girl of the PEG-ELS group who required intravenous fluid for 6 hours because of lethargy and de-hydration (dryness of the oral mucosa and orthostatic hypotension) with se-rum electrolyte and glucose sese-rum levels within the normal range.

No statistically significant difference be-tween the pre- and posttreatment labo-ratory values of kidney, liver function, and serum electrolytes was found (Table 4).

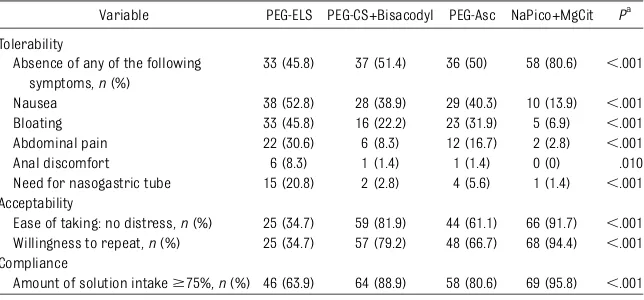

specific symptoms associated with bowel lavage solutions was significantly higher in

the NaPico+MgCit group (80.6%; 95% CI: 70.2–88.5) compared with PEG-ELS (45.8%; 95% CI: 34.6–57.4),

PEG-CS+Bisacodyl (51.4%; 95% CI: 39.9– 62.8), and PEG-Asc (50%; 95% CI: 38.6– 61.4;P,.001).

Nausea, bloating, and abdominal pain were the most commonly reported symptoms

and were significantly lower in the NaPico +MgCit group compared with ELS, PEG-CS+Bysacodyl, and PEG-Asc (P,.001; Ta-ble 5).

Anal irritation was significantly higher in the PEG-ELS group (8.3%; 95% CI: 3.4–16.5) compared with the PEG-CS+Bisacodyl (1.4%; 95% CI: 0.01–6.7), PEG-Asc (1.4%; 95% CI: 0.01–6.7), and NaPico+MgCit (0%; P,.001).

The percentage of children needing nasogastric tube placement for the infusion of the bowel-cleansing solution was significantly lower in the NaPico +MgCit group (1.4%) compared with PEG-ELS (20.8%), PEG-CS+Bysacodyl (2.8%), and PEG-Asc (5.6%;P,.001).

Acceptability and Compliance

The rate of children who stated that the intake of the solution was easy was signif-icantly higher in the NaPico+MgCit (91.7%; 95% CI: 83.5–96.6) compared with PEG-ELS (34.7%; 95% CI: 24.4–46.2), PEG-CS +Bisacodyl (81.9%; 95% CI: 30.3–55.2), and PEG-Asc (61.1%; 95% CI: 49.5–71.8;P,.001).

The rate of children who declared that they would be willing to repeat the same FIGURE 1

Studyflowchart.

TABLE 2 Demographic Characteristics of the Study Groups at Per Protocol Analysis

Variable PEG-ELS

(n= 72)

PEG-CS+Bisacodyl (n= 72)

PEG-Asc (n= 72)

NaPico+MgCit (n= 72)

Sex

Male 42 (58.3) 46 (63.9) 43 (59.7) 36 (50)

Female 30 (41.7) 26 (36.1) 29 (40.3) 36 (50)

Age (y) mean (SD) 12.9 (4.6) 12.3 (4.2) 13 (4.5) 12.2 (4.7)

2–7 y,n(%) 11 (15.3) 10 (13.9) 11 (15.3) 13 (18.1)

8–13 y,n(%) 20 (27.8) 33 (45.8) 20 (27.8) 25 (34.7) 14–18 y,n(%) 41 (56.9) 29 (40.3) 39 (56.9) 34 (47.2) Race,n(%)

White 70 (97.2) 70 (97.2) 70 (97.2) 70 (97.2)

Black 1 (1.4) 1 (1.4) 2 (2.8) 1 (1.4)

Asian 1(1.4) 1(1.4) 0 (0) 1(1.4)

BMI (SD), kg/m2 20.2 (4.1) 20.3 (4.1) 20.6 (4.4) 20 (3.7) Indication for colonoscopy,n(%)

Suspected IBD 7 (9.7) 8 (11.1) 8 (11.1) 5 (6.9)

Bloody stools 13 (18.1) 19 (26.4) 21 (29.2) 17 (23.6)

Known IBD evaluation 46 (63.9) 35 (48.6) 38 (52.8) 40 (55.6)

Abdominal pain 3 (4.2) 4 (5.6) 2 (2.8) 5 (6.9)

Other 3 (4.2) 6 (8.3) 3 (4.2) 5 (6.9)

Constipation before bowel cleanout,n(%) 5 (6.9) 4 (5.6) 7 (9.7) 6 (8.3) Diagnosis at colonoscopy,n(%)

Normal 45 (62.5) 35 (48.6) 42 (58.3) 36 (50)

Colitis (IBD) 23 (31.9) 24 (33.3) 24 (33.3) 24 (33.3)

Polyp 1 (1.4) 10 (13.9) 2 (2.8) 5 (6.9)

Other 3 (4.2) 3 (4.2) 4 (5.6) 7 (9.7)

IBD, inflammatory bowel disease.

preparation regimen if needed was significantly higher in the NaPico+MgCit

(94.4%; 95% CI: 87.1–98.2) compared with PEG-ELS (34.7%; 95% CI: 24.4–46.2), PEG-CS+Bisacodyl (79.2%; 95% CI: 68.7– 87.4), and PEG-Asc (66.7%; 95% CI: 55.2– 76.8;P,.001).

The rate of children taking an amount of solution $75% was significantly higher in the NaPico+MgCit (95.8%; 95% CI: 89.0–98.9) compared with PEG-ELS (63.9%; 95% CI: 52.3–74.3), PEG-CS +Bisacodyl (88.9%; 95% CI: 80.0–94.7), and PEG-Asc (80.6%; 95% CI: 70.2–88.5; P,.001).

DISCUSSION

Since the withdrawal of oral sodium phosphate from the US market, PEG-ELS is among the most commonly used agents for colonoscopy preparation in children, particularly in Europe. How-ever, children do not tolerate well the large volume and salty taste of these solutions, and thus in-patient adminis-tration through nasogastric tube is often required.7 In pediatric clinical trials, PEG-ELS has been more effective than active laxatives, including bisacodyl, senna, and magnesium citrate,5also showing a cleansing effectiveness

In contrast to adults, in whom low-volume PEG solutions represent an important alternative to standard vol-ume formulations,12,13 there are no pediatric data on the use of low-volume PEG solutions.7

Our results showed, for thefirst time in children, that the tested low-volume PEG regimens (PEG-CS+bisacodyl, PEG-Asc) and NaPico+MgCit were noninferior to standard high volume solution (PEG-ELS) in bowel-cleansing efficacy. The high efficacy rate could be due to sev-eral factors. First, nurses expended much time to explain, especially among outpatients, how to take the bowel preparations and how important it is to take them as directed for a good colo-noscopy outcome. Second, all colonos-copies were performed close to the end of the bowel preparation (before 11AM).

This is a factor that is well known to positively influence efficacy rate.14

Our data also confirmed both adult and pediatric data on the safety of NaPico +MgCit compared with PEG-ELS11,15–17 and, for the first time in a pediatric population, with 2 low-volume PEG sol-utions (CS+bisacodyl and PEG-Asc). Indeed, in our series there was no statistically significant difference in the incidence of dehydration or in pre-and posttreatment laboratory values of kidney and liver function and serum

Per protocol population n= 72 n= 72 n= 72 n= 72

Qualitative preparation rating,n(%) NSa

Excellent 30 (41.7) 31 (43.1) 29 (40.3) 31 (43.1)

Good 36 (50) 32 (44.4) 31 (43.1) 34 (47.2)

Poor 6 (8.3) 8 (11.1) 10 (13.9) 6 (8.3)

Inadequate 0 (0) 1 (1.4) 2 (2.8) 1 (1.4)

Successful bowel cleansing,n(%) 66 (91.7) 63 (87.5) 60 (83.3) 65 (90.3) NSb

BBPS score per segment, mean6SD NSc

Right colon 2.13 (0.58) 2.19 (0.66) 2.03 (0.67) 2.11 (0.62) Transverse colon 2.4 (0.52) 2.4 (0.57) 2.32 (0.65) 2.39 (0.59) Left colon 2.38 (0.57) 2.29 (0.61) 2.22 (0.68) 2.43 (0.50) Time to cecum (min), mean6SD 10.7 (4.3) 10.1 (3.5) 10.4 (3.6) 10.1 (3.8) NSd Caecal intubation rate (%) 72 (100) 72 (100) 72 (100) 71 (98.6) NSe Intention-to-treat population N= 75 N= 74 N= 76 N= 74 NSf

Successful bowel cleansing,n(%) 63 (88) 61 (85.1) 56 (78.9) 63 (87.8)

NS, nonsignificant.

aP= .910,x2

test.

bP= .423,x2test.

cPEG-ELS versus PEG-CS: right,P= .5; transverse:P= .9; left,P= .4. PEG-ELS versus PEG-Asc: right,P= .3; transverse:P= .4; left,

P= .1. PEG-ELS versus NaPico+MgCit: right,P= .9; transverse:P= .9; left,P= .5. Student’sttest in all cases.

dPEG-ELS versus PEG-CS (P= .4); PEG-ELS versus PEG-Asc (P= .6); PEG-ELS versus NaPico+MgCit (P= .4). eP= .39,x2test.

fP= .4,x2

test.

TABLE 4 Mean Changes in Laboratory Values

Laboratory Variable PEG-ELS, Mean (SD)

Pa PEG-CS+Bisacodyl, Mean (SD)

Pa PEG-Asc, Mean (SD)

Pa NaPico+MgCit, Mean (SD)

Pa

Sodium (mmol/L) 20.03 (5.10) .969 4.13 (19.98) .584 4.14 (19.97) .583 4.97 (23.25) .742 Potassium (mmol/L) 20.06 (0.60) .440 20.05 (0.58) .529 20.04 (0.56) .530 20.16 (0.54) .120

Chloride (mmol/L) 0.86 (5.71) .202 0.45 (5.47) .472 0.46 (5.50) .471 0.46 (5.50) .068

Magnesium (mmol/L) 0.00 (0.13) .517 0.01 (0.13) .517 0.00 (0.14) .520 0.00 (0.13) .549

Calcium (mmol/L) 0.02 (0.27) .650 0.03 (0.30) .471 0.02 (0.28) .467 20.04 (0.27) .103

Phosphorus (mmol/L) 0.09 (0.38) .077 0.08 (0.39) .094 0.07 (0.40) .172 0.12 (0.37) .078

Creatinine (mg/dL) 0.00 (0.36) .862 0.02 (0.32) .591 0.00 (0.34) .985 0.05 (0.36) .244

AST (U/L) 20.78 (15.01) .970 0.06 (14.54) .484 21.25 (16.78) .807 0.54 (12.70) .560

ALT (U/L) 20.64 (12.84) .575 20.31 (12.40) .795 20.07 (12.50) .904 22.79 (10.48) .058

g-GT (U/L) 0.80 (7.88) .368 0.87 (9.67) .531 1.29 (10.14) .239 21.04 (9.47) .669

ALT, alanine transaminase; AST, aspartate transaminase; GT, glutamyl transpeptidase.

electrolytes in the 4 study groups. There was only 1 clinical adverse event in a 10-year-old girl from the PEG-ELS group who required intravenousfluid.

The clinical relevance of our study is also related with the different tolera-bility and acceptatolera-bility profile of the four bowel-cleansing solutions. Indeed, our data showed that NaPico+MgCit appeared to be noninferior to the other solutions but better tolerated and accepted than both the standard high-volume preparation and the 2 low-volume PEG solutions. In our opinion, the higher tolerability and acceptability of NaPico+MgCit accounts, at least partially, for the noninferior efficacy of this regimen compared with the stan-dard 4-L PEG preparation. In contrast, the 4-L PEG presented with an opposite ratio between efficacy and compliance.

Meta-analyses in adult patients have shown that the use of a split-dose of PEG for bowel preparation significantly improved the number of satisfactory bowel prepa-rations, increased patient compliance, and decreased nausea compared with the full-dose PEG.18We did not use this approach because in our unit, colonoscopy was performed early in the morning, which made it impossible to use this bowel preparation method. We acknowledge that this could also be a promising ap-proach in children, and future studies are warranted to test this hypothesis. The main limitations of the present anal-ysis are the single-center design; however, the assessment of the efficacy was per-formed by 3 endoscopists blinded to the method of the preparation, which makes our results less prone to performance bias. Second, the majority of patients had

suspected or known inflammatory bowel disease as an indication for the colonos-copy; this is mainly related to the setting of the study and could potentially limit the generalizability of the results. Third, the bowel cleansing was performed in both outpatient and inpatient settings; however, most of the procedures were performed on outpatients (∼95%), ensuring the generalizability of the study results. Fourth, because of the lack of compara-tive studies, we adopted a 3-day period of low-residue diet before colonoscopy, irrespectively of the regimen adopted. We cannot exclude that a shorter period would have similarly decreased the mean level of bowel cleansing in all the groups.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, our study shows for the

first time in children that low-volume PEG preparations (PEG-CS+Bisacodyl and PEG-Asc) and NaPico+MgCit are non-inferior to PEG-ELS for bowel preparation before colonoscopy in children. NaPico +MgCit also appear to be better toler-ated, representing a promising regimen for bowel preparation in children.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Alessandra Persi and Debora Panattoni for undertaking the impor-tant role of dispensing the products and explaining how they should be taken.

REFERENCES

1. Lee KK, Anderson MA, Baron TH, et al; ASGE Standards of Practice Committee. Mod-ifications in endoscopic practice for pediatric patients.Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67(1):1–9 2. Froehlich F, Wietlisbach V, Gonvers JJ, Burnand B, Vader JP. Impact of colonic cleansing on quality and diagnostic yield of colonoscopy: the European Panel of Ap-propriateness of Gastrointestinal Endos-copy European multicenter study.Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61(3):378–384

3. Belsey J, Epstein O, Heresbach D. System-atic review: oral bowel preparation for

colonoscopy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25(4):373–384

4. Barkun A, Chiba N, Enns R, et al. Commonly used preparations for colonoscopy: efficacy, tolerability, and safety—a Canadian Associ-ation of Gastroenterology position paper.

Can J Gastroenterol. 2006;20(11):699–710 5. Dahshan A, Lin CH, Peters J, Thomas R,

Tolia V. A randomized, prospective study to evaluate the efficacy and acceptance of three bowel preparations for colonoscopy in children. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94 (12):3497–3501

6. Hunter A, Mamula P. Bowel preparation for pediatric colonoscopy procedures.J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2010;51(3):254–261 7. Turner D, Levine A, Weiss B, et al; Israeli

Society of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition (ISPGAN). Evidence-based recom-mendations for bowel cleansing before colonoscopy in children: a report from a national working group.Endoscopy. 2010; 42(12):1063–1070

8. Lewis SJ, Heaton KW. Stool form scale as a useful guide to intestinal transit time.

Scand J Gastroenterol. 1997;32(9):920–924

TABLE 5 Secondary End Points at Per Protocol Analysis

Variable PEG-ELS PEG-CS+Bisacodyl PEG-Asc NaPico+MgCit Pa

Tolerability

Absence of any of the following symptoms,n(%)

33 (45.8) 37 (51.4) 36 (50) 58 (80.6) ,.001

Nausea 38 (52.8) 28 (38.9) 29 (40.3) 10 (13.9) ,.001

Bloating 33 (45.8) 16 (22.2) 23 (31.9) 5 (6.9) ,.001

Abdominal pain 22 (30.6) 6 (8.3) 12 (16.7) 2 (2.8) ,.001

Anal discomfort 6 (8.3) 1 (1.4) 1 (1.4) 0 (0) .010

Need for nasogastric tube 15 (20.8) 2 (2.8) 4 (5.6) 1 (1.4) ,.001 Acceptability

Ease of taking: no distress,n(%) 25 (34.7) 59 (81.9) 44 (61.1) 66 (91.7) ,.001 Willingness to repeat,n(%) 25 (34.7) 57 (79.2) 48 (66.7) 68 (94.4) ,.001 Compliance

Amount of solution intake$75%,n(%) 46 (63.9) 64 (88.9) 58 (80.6) 69 (95.8) ,.001

ax2test.

tion Scale: a valid and reliable instru-ment for colonoscopy-oriented research.

Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69(3 pt 2): 620–625

10. Shawki S, Wexner SD. Oral colorectal cleansing preparations in adults. Drugs. 2008;68(4):417–437

11. Turner D, Benchimol EI, Dunn H, et al. Pico-Salax versus polyethylene glycol for bowel cleanout before colonoscopy in children: a randomized controlled trial. Endoscopy. 2009;41(12):1038–1045

12. Repici A, Cestari R, Annese V, et al. Randomised clinical trial: low-volume bowel preparation for colonoscopy—a comparison between two

dif-13. Cohen LB, Sanyal SM, Von Althann C, et al. Clinical trial: 2-L polyethylene glycol-based la-vage solutions for colonoscopy preparation— a randomized, single-blind study of two for-mulations. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;32 (5):637–644

14. Seo EH, Kim TO, Park MJ, et al. Optimal preparation-to-colonoscopy interval in split-dose PEG bowel preparation determines satisfactory bowel preparation quality: an observational prospective study.Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75(3):583–590

15. Hamilton D, Mulcahy D, Walsh D, Farrelly C, Tormey WP, Watson G. Sodium picosulphate compared with polyethylene glycol solution

16. Ryan F, Anobile T, Scutt D, Hopwood M, Murphy G. Effects of oral sodium picosulphate Picolax on urea and electrolytes.Nurs Stand. 2005;19(45): 41–45

17. Yoshioka K, Connolly AB, Ogunbiyi OA, Hasegawa H, Morton DG, Keighley MR. Randomized trial of oral sodium phosphate compared with oral so-dium picosulphate (Picolax) for elective co-lorectal surgery and colonoscopy.Dig Surg. 2000; 17(1):66–70

18. Kilgore TW, Abdinoor AA, Szary NM, et al. Bowel preparation with split-dose poly-ethylene glycol before colonoscopy: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials.

Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73(6):1240–1245

BIRDING IN THE ELECTRONIC AGE:I have an aunt who is an avid birder. She can identify an innumerable number of birds both by sight and the calls they make. She occasionally competes in birding competitions where she tries to identify as many birds as possible in a limited amount of time. When she does compete, she only brings her binoculars andfield notes. Evidently, that is an old school ap-proach. As reported inThe New York Times(City Room: May 10, 2014), the world of competitive birding is struggling with how to incorporate the use of technology. Younger birders may compete with expensive cameras, smartphones laden with digitalfield guides, applications that play recordings of bird songs, GPS, and even maps suggesting the best places tofind specific birds. At the heart of the issue is whether the honor system inherent in birding is simply outdated. Birding com-petitions do not require proof of a sighting, relying solely on the honesty of the contestants. Questionable sightings, called stringing, may result from in-experienced birders eager to identify birds or, more deviously, cheating. While it is unclear that more birders are cheating in competitions, one reason to require photographic proof of a sighting, particularly of a rare bird, is to combat stringing. On a happier note, one reason to embrace technology is that it allows more and younger enthusiasts to engage in the sport. Even those that eschew the use of technology agree that anything that increases the popularity of the sport and helps protect bird habitats is welcome, but that some balance must be struck. After all, it is likely that sometime in the near future binoculars used for birding will come equipped with programs that identify the birds, removing all skill involved. As for me, I prefer walking with my aunt without any special equipment. I take her word that the song we heard was indeed that of a specific bird and simply enjoy our time together.

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2014-0131 originally published online July 7, 2014;

2014;134;249

Pediatrics

Lima, Giuseppe La Torre and Salvatore Oliva

Hassan, Fortunata Civitelli, Federica Nuti, Chiara Ziparo, Andrea Pession, Mario

Giovanni Di Nardo, Marina Aloi, Salvatore Cucchiara, Cristiano Spada, Cesare

Bowel Preparations for Colonoscopy: An RCT

Services

Updated Information &

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/134/2/249 including high resolution figures, can be found at:

References

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/134/2/249#BIBL This article cites 18 articles, 0 of which you can access for free at:

Subspecialty Collections

sub

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/orthopedic_medicine_ Orthopaedic Medicine

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/gastroenterology_sub Gastroenterology

following collection(s):

This article, along with others on similar topics, appears in the

Permissions & Licensing

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/Permissions.xhtml in its entirety can be found online at:

Information about reproducing this article in parts (figures, tables) or

Reprints

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2014-0131 originally published online July 7, 2014;

2014;134;249

Pediatrics

Lima, Giuseppe La Torre and Salvatore Oliva

Hassan, Fortunata Civitelli, Federica Nuti, Chiara Ziparo, Andrea Pession, Mario

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/134/2/249

located on the World Wide Web at:

The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is

by the American Academy of Pediatrics. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 1073-0397.