Mariantonietta Di Stefano1, Anna Volpe2, Giovanni Stallone3, Luciano Tartaglia3, Rosa Prato4, Domenico Martinelli4, Giuseppe Pastore2, Loreto Gesualdo1,3, Josè Ramòn Fiore5

M. Di Stefano and A. Volpe contributed equally to this paper.

1 Laboratory of Molecular Medicine, University of Foggia, Foggia - Italy

2 Clinic of Infectious Diseases, University of Bari, Bari - Italy

3 Division of Nephrology, University of Foggia, Foggia - Italy

4 Hygiene Section, Department of Clinical and Occupatio-nal Sciences, University of Foggia, Foggia - Italy

5 Department of Clinical and Occupational Sciences, University of Foggia, Foggia - Italy

Occult HBV infection in hemodialysis setting is

marked by presence of isolated antibodies to

HBcAg and HCV

A

bstrActBackground: Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infections are a matter of concern in hemodialysis units; occult HBV infections (serum HBsAg negative but HBV DNA posi-tive) were demonstrated in this setting, and this in-volves further concerns regarding possible transmis-sion and pathogenic consequences. This study aimed to investigate the prevalence and correlates of occult HBV infection in a group of patients with reference to a single hemodialysis unit in southeastern Italy. Methods: We analyzed HBV serology and DNA (using a qualitative nested PCR) in 128 HBsAg-negative hemodi-alysis patients, and correlated the results obtained, with sex, age, hemodialysis duration and HCV seropositivity. Results: As a whole, occult HBV infection was dem-onstrated in 34/128 patients (26.6%); HBV DNA detec-tion was more frequent when anti-HBcAg antibodies were detected in isolation (72%) than when associated with anti-HBsAg antibodies (31%). Among HCV-sero-positive patients, occult HBV infection was observed in 66%, and among these as many as 14/15 patients (93%) who were HCV+/anti-HBcAg+ had serum HBV DNA detectable. On multivariate analysis, HCV sero-positivity and the presence of anti-HBs were still re-spectively correlated to the presence and absence of occult HBV infection. Conclusions: Occult HBV infec-tion is frequent among hemodialysis patients in our geographical area, particularly correlated to the pres-ence of isolated anti-HBcAg and anti-HCV

antibod-I

ntroductIonHepatitis B virus (HBV) and C virus (HCV) infections are the most important infectious causes of morbidity and mortal-ity in maintenance hemodialysis (HD) patients (1, 2). In the setting of HBV infection, several studies demonstrated that subjects carrying serum antibodies to HBV core antigen (HBcAg) and/or to HBV surface antigen (HBsAg) may har-bor HBV DNA in serum and/or liver despite the absence of serum HBsAg. This condition is now termed occult hepati-tis B infection (3, 4).

Occult hepatitis B has been reported in a number of pa-tient subgroups including those with HCV infection, HIV-1 infection and hepatocellular carcinoma (5, 6). The preva-lence of occult HBV infection varies in different geograph-ic areas in the world, although its distribution may reflect the general prevalence of HBV infection (6).

Several studies reported a high prevalence (>50%) of occult HBV infection among patients with chronic liver disease (7,-9), whereas among HIV-infected patients, the prevalence showed more variability among different

ies. Thus, the presence of isolated anti-HBcAg should prompt the clinician to evaluate a possible occult HBV infection especially if anti-HCV antibodies are also de-tectable; this condition, in fact, seems to strongly pre-dict the detection of HBV DNA.

Key words: Anti-HCV, Occult HBV infection, Hemodi-alysis, Isolated anti-HBcAg

studies – between 10% (10) and 89.5% (11). In injecting drug users, a high prevalence of occult HBV infection was reported (45%), while a low prevalence (4.86%) was dem-onstrated in blood donors (12).

Nevertheless, controversial prevalence data have been reported in patients receiving HD, with a range from 0% (13) to 58% (14). These discrepant results may be due to variable seroprevalences in geographically different study populations, to the type of HBV DNA assay employed, as well as to the criteria used to define occult HBV infection. To date in fact, such a definition is quite heterogeneous among different studies, including patients with detect-able HBV DNA either in blood or in liver or both.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the prevalence of occult HBV infection in a population of HD patients from southeastern Italy in relation to age, sex, time of dialysis and HCV infection.

P

AtIents,

mAterIAl Andmethods PatientsOne hundred and twenty-eight white patients, referred for maintenance HD to the Nephrology Division of the Univer-sity of Foggia, Foggia, Italy, were included in the study. The etiology of renal failure was chronic glomerulonephri-tis, pyelonephriglomerulonephri-tis, hypertension and nephrosclerosis, dia-betic nephropathy or polycystic kidney disease. None of the patients included had undergone a kidney transplant.

Serology and HBV DNA detection

The remaining sera from routine laboratory analysis were anonymously obtained, with the main general information for each patient, and tested for markers of hepatitis B virus infection (anti-HBs, anti-HBc and HBsAg) by a commercial-ly available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (Architect System Abbott, Wiesbaden, Germany) according to manufacturer’s instructions.

All samples were also tested for hepatitis C virus antibod-ies by ELISA using a commercially available kit (Architect System Abbott, Wiesbaden, Germany). Serum HBV DNA was tested for using a nested HBV polymerase chain reac-tion (PCR) kit according to the manufacturer’s instrucreac-tions (Ampliquality HBV; AB Analitica, Padova, Italy). Briefly, viral DNA was extracted from 200 μL of serum and dissolved in TE buffer. After this step, the HBV core region was ampli-fied by using a nested PCR for a final 258-bp ampliampli-fied product. The amplified fragment was separated in 3% aga-rose gel and stained with ethidium bromide. The sensitivity limit of nested PCR was 10-5 pg of HBV DNA in the sample, corresponding to 15 copies of HBV DNA/mL of serum Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed by conventional chi-square test with Yates correction with an odds ratio cal-culation. Results were considered significant for a p value <0.05. Multivariate analysis was carried out to assess the presence of any independent and significant link between

TABLE I

CHARACTERISTICS OF HBsAg-NEGATIVE HEMODIAYSIS PATIENTS IN RELATION TO HBV SEROLOGICAL PATTERNS

Characteristic HBV serological pattern

HBcAb-/HBsAb- HBcAb-/HBsAb+ HBcAb+/HBsAb- HBcAb+/HBsAb+

Serological pattern, no. (%) 38 (29.6%) 14 (11%) 25 (19.5%) 51 (40%)

Sex, male/female 22/16 6/8 15/10 30/21

Age, mean age, years 65.05 ± 17.04 59.5 ± 20.25 68.76 ± 7.77 66.64 ± 13.7

Hemodialysis duration,

occult HBV and additional parameters such as sex, age, HBsAb, anti-HCV and history of dialysis.

r

esultsThe group of HD patients enrolled in the study consisted of 73 men and 55 women; their mean age was 65 years (range 17-91 years). The mean time of HD duration was 88.34 months (Tab. I). All of the patients were confirmed to be HBsAg negative.

The serological markers for HBV were studied. As shown in Table I, in 90/128 of HD individuals (70.3%), antibodies to HBV antigen were detected, while the remaining 38 (29.7%) were negative for antibodies to HBV.

According to the serological patterns of antibodies to HBV, patients were divided into 4 subgroups: anti-HBs+/anti-HBc+ (51 patients; 40%); anti-HBs-/anti-anti-HBs+/anti-HBc+ (25 patients; 19.5%); HBs+/HBc- (14 patients; 11%); and anti-HBs-/anti-HBc- (38 patients; 29.6%) (Tab. I).

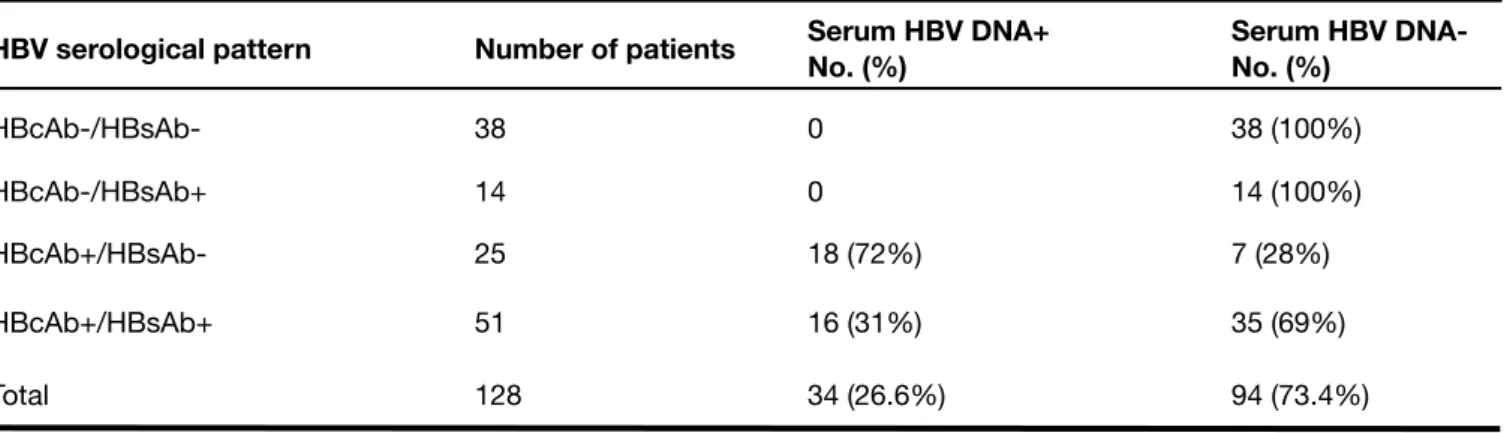

Next, we determined the presence of serum HBV DNA (Tab. II). Among the 128 HD patients, HBV DNA was detected in 34 out of 128 subjects (26.6%). This occurred in 16 out of 51 HD patients (31%) with both anti-HBsAg and anti-HBcAg, and in 18 out of 25 HD patients (72%) who harbored serum isolated antibodies to HBcAg (p=0.000854). No serum HBV DNA was detected in patients with anti-HBsAg alone and/ or in HBV-seronegative patients. As a whole, HBV DNA was thus detected only in the presence of anti-HBcAg, either

TABLE II

DETECTION OF HBV DNA IN SERA OF HBsAg-NEGATIVE HEMODIALYSIS PATIENTS WITH DIFFERENT HBV SEROLOGICAL PATTERNS

HBV serological pattern Number of patients Serum HBV DNA+No. (%) Serum HBV DNA-No. (%)

HBcAb-/HBsAb- 38 0 38 (100%) HBcAb-/HBsAb+ 14 0 14 (100%) HBcAb+/HBsAb- 25 18 (72%) 7 (28%) HBcAb+/HBsAb+ 51 16 (31%) 35 (69%) Total 128 34 (26.6%) 94 (73.4%) TABLE III

CORRELATION BETWEEN SERUM HBV DNA, ANTI HCV ANTIBODIES AND HBV SEROLOGICAL PATTERNS

HCV serology Number of patients Serum HBV DNA

HBV serological pattern HBcAb-/HBsAb-No. (%) HBcAb-/HBsAb+ No. (%) HB-cAb+/ HBsAb-No. (%) HBcAb+/ HBsAb+ No. (%) Anti-HCV+ 21 HBV DNA+ 0 5 (20%) 0 9 (17.6%) HBV DNA- 4 (10.5%) 0 2 (14%) 1 (1.96%) Anti-HCV- 107 HBV DNA+ 0 13 (52%) 0 7 (13.7%) HBV DNA- 34 (89.6%) 7 (28%) 12 (86%) 34 (66.6%) Total 128 38 25 14 51

alone or in association with anti-HBsAg: namely, in 34/76 patients (44.7%; p=0.000001). No significant correlation was found among occult HBV infection and sex, age or dia-lytic age of the HD patients enrolled in our study (p=ns). Regarding HCV infection (Tab. III), we found that 21 of 128 of HD patients (16.4%) were anti-HCV positive. We further correlated the presence of HBV DNA with HCV seropositiv-ity, and we found that 14 of 21 HCV seropositive individu-als (66.7%) harbored HBV DNA in serum as detected by PCR, versus 20/107 HCV seronegative individuals (18.7%; p=0.0000058).

HBV DNA was detected more frequently in anti-HCV+/ anti-HBcAg+ patients (14/15, 93%) than in anti-HCV-/anti-HBcAg+ patients (20/61, 32.7%) (p=0.000027).

Multivariate analysis showed a significant association be-tween HBV DNA presence and HCV coinfection (odds ratio [OR] = 67.9; 95% confidence interval [95% CI], 6.5-707.6; p<0.001) and a significant inverse association with the presence of HBsAb (OR=0.08; 95% CI, 0.02-0.3; p<0.001), meaning the presence of HBsAb is protective against oc-cult HBV infection.

d

IscussIonHBV infection is usually diagnosed when circulating HBsAg is detected in the serum of patients. Several reports have demonstrated that HBV genomes may also be present in blood and/or liver in spite of the absence of HBsAg in se-rum, a condition now termed occult HBV infection, which might have several implications especially for transmis-sion. The inoculation of human sera derived from individuals negative for all HBV serological markers but HBV DNA posi-tive induced acute hepatitis in an animal model (15), thus suggesting that low HBV DNA inocula may also induce viral infection (15). In addition, transmission of HBV infection by transfusion of blood carrying serologically silent HBV infec-tion was reported (16, 17); although rare in the Western world (18), in countries such as India or Taiwan, the incidence of post-transfusional hepatitis B due to transfusion of blood from HBsAg-negative donors is still far from negligible (6). In the setting of transplants, occult HBV infected grafts may cause de novo infections after liver transplant (19, 20); this event is instead rare for kidney or heart transplants (21). Also, nosocomial transmissions of occult HBV infection in dialysis patients and staff has been reported (22).

From a clinical point of view, several aspects deserve con-sideration. Reactivation of occult HBV infection may occur in conditions of immunodeficiency or suppression (hema-tological malignancies, HIV infection, hemopoietic stem cell and organ transplantation) (6, 23). Furthermore, occult

HBV infection has been clearly associated with more ad-vanced evolution to fibrosis and cirrhosis (24) and with a poor response to interferon treatments (25), in HCV-infect-ed individuals.

HD units are known to be at increased risk for bloodborne viral infections; blood transfusions and/or percutaneous or permucosal exposure to infected blood or body fluids or contaminated equipment may in fact occur in these units. We thus evaluated the frequency of detection of occult HBV infection in a group of chronic HD patients negative for se-rum HBsAg. We demonstrated HBV DNA in 34/128 (26.6%) of the individuals enrolled in the study. This finding is in be-tween those published by Cabrerizo et al (26), Joller-Jemel-ka et al (14) and Besisik et al (27) – these authors found HBV DNA in 58%, 40% and 36% of HBsAg-negative HD patients, respectively – and those from other studies that reported low HBV DNA recovery in HD patients from North America (3.8%) (28), Turkey (0%) (29) and Italy (0%) (13).

Several explanations may be put forward for these discrep-ant results: differences in the sensitivity of the methods used for detection of HBV DNA, different prevalences of HBV in a geographical area, and differences in the storage and age of serum samples used in the studies. In addition, the discrep-ancies with the results from the above-mentioned study on Italian patients (13) are not surprising, because of the very low rate of HBV infection (1.88%) observed by the authors; other reports indicate a prevalence of HBV infection in Italian HD patients ranging from 4.5% to 8.7% (30).

The data presented here clearly indicate that the presence of serum HBV DNA is significantly correlated to the detection of anti-HBcAg, either alone (72%) or associated with anti-HB-sAg (31%). No HBV DNA was in fact detectable in individuals negative for antibodies to HBV or positive only for anti-HBsAg. This is partially in line with previous reports, where HBV DNA was detectable more frequently in anti-HBcAg-positive rather than in anti-HBcAg-negative individuals (7). Thus, the condi-tion of isolated anti-HBsAg antibodies is strongly correlated to, but does not predict, occult HBV infection.

HCV infection is reported as a significant correlate of oc-cult HBV infection in several subgroup of patients (31); this association was demonstrated also, in our study, in the HD setting as well, since the majority of anti-HCV-positive indi-viduals (66%) also had detectable serum HBV DNA. These results are in line with published data indicating that, in HD patients, the presence of isolated anti-HBcAg is sig-nificantly correlated to the presence of anti-HCV antibodies (13); in addition, occult HBV infection was more frequently detected in chronically HCV-infected patients in some re-ports (13), but not in others (22, 29). Our findings – that is that occult HBV infection is correlated to the detection of

anti-HCV antibodies – is not surprising, given that both in-fections share the same modalities of transmission. This study was designed mainly as a serological study, and this might be regarded as a limit. We do not provide information on the correlations between serological data and clinical characteristics of patients enrolled in the study, as well as on their eventual HBV vaccination schedules. Samples were obtained in an anonymous fashion, and thus these data were not available. But we still believe that the data presented here add important information in the field of occult HBV infection in the HD setting.

Although the clinical significance of occult HBV infection, as well as its relevance for transmission, is not clearly de-fined, one should carefully consider this phenomenon in the HD units, where unrecognized infections can easily spread. We suggest that in the presence of anti-HBcAg antibodies, either alone or in association with anti-HBsAg antibodies, especially if anti-HCV antibodies are also de-tected, steps should be taken to rule out the possibility of

occult HBV infection in HD patients.

The possibility of vaccination schedules in cases of occult HBV infection could also be considered, since studies have demonstrated that this might cause the disappearance of HBV DNA from the blood (32).

Financial support: This work was supported in part by grants from the Istituto Superiore di Sanità (Progetto AIDS) and from institutional grants to J.R.F. from the University of Foggia. Conflict of interest statement: None declared.

Address of correspondence:

Josè Ramòn Fiore, MD, PhD

Department of Clinical and Occupational Sciences University of Foggia, School of Medicine

Viale Pinto

I-71100 Foggia, Italy jrfiorevirlab@yahoo.com

r

eferencesHuang CC. Hepatitis in patients with end-stage renal disease. 1.

J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1997;12:236-241.

Zacks SL, Fried MW. Hepatitis B and C renal failure. Infect Dis 2.

Clin North Am. 2001;15:877-899.

Brechot C, Thiers V, Kremsdorf D, Nalpas B, Pol S, Paterlini-3.

Brechot P. Persistent hepatitis B virus infection in subjects without hepatitis B surface antigen: clinically significant or purely “occult”? Hepatology. 2001;34:194-203.

Torbenson M, Thomas DL. Occult hepatitis B. Lancet Infect 4.

Dis. 2002;2:479-486.

Allain JP. Occult hepatitis B virus infection: implications in 5.

transfusion. Vox Sang. 2004;86:83-91.

Raimondo G, Pollicino T, Cacciola I, Squadrito G. Occult hep-6.

atitis B virus infection. J Hepatol. 2007;46:160-170.

Cacciola I, Pollicino T, Squadrito G, Cerenzi G, Orlando 7.

ME, Raimondo G. Occult hepatitis B virus infection in pa-tients with chronic hepatitis C liver disease. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:22-26.

Fabris P, Brown D, Tositti G, et al. Occult hepatitis B virus in-8.

fection does not affect liver histology or response to therapy with interferon alpha and ribavirin in intravenous drug users with chronic hepatitis C. J Clin Virol. 2004;29:160-166. Kazemi-Shirazi L, Petermann D, Muller C. Hepatitis B virus 9.

DNA in sera and liver tissue of HBsAg negative patients with chronic hepatitis C. J Hepatol. 2000;33:785-790.

Lo Re V 3rd, Frank I, Gross R, et al. Prevalence, risk fac-10.

tors, and outcomes for occult hepatitis B virus infection among HIV-infected patients. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;44:315-320.

Hofer M, Joller-Jemeka HI, Grob PJ, Luthy R, Opravil M. 11.

Frequent chronic hepatitis B virus infection in HIV-infected patients positive for antibody to hepatitis B core antigen only. Swiss HIV cohort study. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1998;17:6-13.

Manzini P, Girotto M, Borsotti R, et al. Italian blood donors 12.

with anti-HBc and occult hepatitis B virus infection. Hemato-logica. 2007;92:1664-1670.

Fabrizi F, Messa PG, Lunghi G, et al. Occult hepatitis B virus 13.

infection in dialysis patients: a multicentre survey. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;21:1341-1347.

Joller-Jemelka HI, Wicki AN, Grob PJ. Detection of HBs 14.

antigen in “anti-HBc alone” positive sera. J Hepatol. 1994;21:269-272.

Thiers V, Nakajima E, Kremsdorf D, et al. Transmission of 15.

hepatitis B from hepatitis-B-seronegative subjects. Lancet. 1988;2:1273-1276.

Larsen J, Hetland G, Skaug K. Posttransfusion hepatitis B 16.

transmitted by blood from a hepatitis B surface antigen-neg-ative hepatitis B virus carrier. Transfusion. 1990;30:431-432. Baginski I, Chemin I, Hantz O, et al. Transmission of serologically 17.

silent hepatitis B virus along with hepatitis C virus in two cases of posttransfusion hepatitis. Transfusion. 1992;32:215-220. Regan FA, Hewitt P, Barbara JA, Contreras M. Prospective 18.

recipi-ents of over 20 000 units of blood. TTI Study Group. BMJ. 2000;320:403-406.

Wachs ME, Amend WJ, Ascher NL, et al. The risk of transmis-19.

sion of hepatitis B from HBsAg(-), HBcAb(+), HBIgM(-) organ donors. Transplantation. 1995;59:230-234.

Uemoto S, Sugiyama K, Marusawa H, et al. Transmission 20.

of hepatitis B virus from hepatitis B core antibody-positive donors in living related liver transplants. Transplantation. 1998;65:494-499.

De Feo TM, Poli F, Mozzi F, Moretti MP, Scalamogna M; Col-21.

laborative Kidney, Liver and Heart North Italy Transplant Pro-gram Study Groups. Risk of transmission of hepatitis B virus from anti-HBC positive cadaveric organ donors: a collabora-tive study. Transplant Proc. 2005;37:1238-1239.

Kanbay M, Gur G, Akcay A, et al. Is hepatitis C virus positivity 22.

a contributing factor to occult Hepatitis B Virus infection in hemodialysis patients? Dig Dis Sci. 2006;51:1962-1966. Iwai K, Tashima M, Itoh M, et al. Fulminant hepatitis B fol-23.

lowing bone marrow transplantation in an HBsAg-negative, HBsAb-positive recipient; reactivation of dormant virus dur-ing the immunosuppressive period. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2000;25:105-108.

De Maria N, Colantoni A, Friedlander L, et al. The impact of 24.

previous HBV infection on the course of chronic hepatitis C. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:3529-3536.

Fukuda R, Ishimura N, Niigaki M. Serologically silent hepatitis 25.

B virus coinfection in patients with hepatitis C virus-associat-ed chronic liver disease: clinical and virological significance. J Med Virol. 1999;58:201-207.

Cabrerizo M, Bartolomé J, De Sequera P, Caramelo C, Car-26.

reño V. Hepatitis B virus DNA in serum and blood cells of hepatitis B surface antigen-negative hemodialysis patients and staff. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1997;8:1443-1447.

Besisik F, Karaca C, Akyuz F, et al. Occult HBV infection and 27.

YMDD variants in hemodialysis patients Wight chronic HCV infection. J Hepatol., 2003;38:506-510.

Minuk GY, Sun DF, Greenberg R, et al. Occult hepatitis B vi-28.

rus infection in a North American adult hemodialysis patient population. Hepatology. 2004;40:1072-1077.

Goral V, Ozkul H, Tekes S, Sit D, Kadiroglu AK. Prevalence 29.

of occult HBV infection in hemodialysis patients with chronic HCV. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:3420-3424.

Burdick RA, Bragg-Gresham JL, Woods JD, et al. Pattern 30.

of hepatitis B prevalence and seroconversion in hemodi-alysis units from three continents: the DOPPS. Kidney Int. 2003;63:2222-2229.

Georgiadou SP, Zachou K, Rigopoulou E, et al. Occult hepati-31.

tis B virus infection in Greek patients with chronic hepatitis C and in patients with diverse nonviral hepatic diseases. J Viral Hepat. 2004;11:358-365.

Pereira JS, Gonçales NS, Silva C, et al. HBV vaccina-32.

tion of HCV-infected patients with occult HBV infection and anti-HBc-positive blood donors. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2006;39:525-531.

Received: May 20, 2008 Revised: July 07, 2008 Accepted: October 09, 2008