DEEP NECK INFECTION: ANALYSIS OF 185 CASES

Tung-Tsun Huang, MD,1Tien-Chen Liu, MD,2Peir-Rong Chen, MD,1Fen-Yu Tseng, MD,3 Te-Huei Yeh, MD,2Yuh-Shyang Chen, MD2

1

Department of Otolaryngology, Buddhist Tzu Chi General Hospital, Hualien, Taiwan

2Department of Otolaryngology, National Taiwan University Hospital, No 7, Chung-Shan

South Road, Taipei 100, Taiwan. E-mail: sos008@ha.mc.ntu.edu.tw

3

Department of Internal Medicine, National Taiwan University Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan Accepted 6 January 2004

Published online 3 June 2004 in Wiley InterScience (www.interscience.wiley.com). DOI: 10.1002/hed.20014

Abstract: Purpose. This study reviews our experience with deep neck infections and tries to identify the predisposing factors of life-threatening complications.

Methods. A retrospective review was conducted of patients who were diagnosed as having deep neck infections in the Department of Otolaryngology at National Taiwan University Hos-pital from 1997 to 2002. Their demographics, etiology, associated systemic diseases, bacteriology, radiology, treatment, duration of hospitalization, complications, and outcomes were reviewed. The attributing factors to deep neck infections, such as the age and systemic diseases of patients, were also analyzed.

Results. One hundred eighty-five charts were recorded; 109 (58.9%) were men, and 76 (41.1%) were women, with a mean age of 49.5F20.5 years. Ninety-seven (52.4%) of the patients were older than 50 years old. There were 63 patients (34.1%) who had associated systemic diseases, with 88.9% (56/63) of those having diabetes mellitus (DM). The parapharyngeal space (38.4%) was the most commonly involved space. Odontogenic infections and upper airway infections were the two most common causes of deep neck infections (53.2% and 30.5% of the known causes). Streptococcus viridansandKlebsiella pneumoniaewere the most common organisms (33.9%, 33.9%) identified through pus cultures.K. pneumoniaewas also the most common infective

organism (56.1%) in patients with DM. Of the abscess group (142 patients), 103 patients (72.5%) underwent surgical drainages. Thirty patients (16.2%) had major complications during admis-sion, and among them, 18 patients received tracheostomies. Those patients with underlying systemic diseases or complica-tions or who received tracheostomy tended to have a longer hospital stay and were older. There were three deaths (mortality rate, 1.6%). All had an underlying systemic disease and were older than 72 years of age.

Conclusions. When dealing with deep neck infections in a high-risk group (older patients with DM or other underlying systemic diseases) in the clinic, more attention should be paid to the prevention of complications and even the possibility of death. Early surgical drainage remains the main method of treating deep neck abscesses. Therapeutic needle aspiration and conservative medical treatment are effective in selective cases such as those with minimal abscess formation.A2004 Wiley Periodicals, Inc. Head Neck 26:854 – 860, 2004

Keywords: neck abscess; cellulitis; diabetes mellitus; trache-ostomy

D

eep neck infection means infection in the potential spaces and fascial planes of the neck, either abscess formation or cellulitis. Deep neck infection was a serious and potentially life-threatening infection in the past. With improvedCorrespondence to:Y.-S. Chen B2004 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

diagnostic techniques, widespread availability of antibiotics, and early surgical intervention today, the mortality rate has decreased significantly compared with that of early reports.1 – 3However, deep neck infections continue to occur relatively frequently in older patients with systemic dis-eases. Complications can even result in death. Therefore, despite the wide use of antibiotics, deep neck infections should not be ignored.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study is based on the records of patients diag-nosed with deep neck infections in the Depart-ment of Otolaryngology at National Taiwan University Hospital between 1997 and 2002. Su-perficial cellulitis or abscesses, limited intraoral abscesses, peritonsillar abscesses, cervical necro-tizing fasciitis, and infections secondary to pene-trating or surgical neck trauma were excluded from this study. Those who did not complete the treatment were also excluded. Ultimately, 185 pa-tients were included in this study. Their demog-raphy, etiology, underlying systemic diseases, bacteriology, radiology, treatment, durations of hospital stay, complications, and outcomes were reviewed and analyzed. The involved spaces were divided according to the description published previously4,5 and included Ludwig’s angina and the following spaces in our series: submandibular, parapharyngeal, carotid, retropharyngeal, ante-rior cervical, posteante-rior cervical, parotid, prever-tebral, masticatory, and pretracheal space. The

FIGURE 1. Age distribution of 185 patients with deep neck infections.

Table 1.Distribution of the space and character of deep neck infections.

No. complications Space/Character

No. patients (%) (N= 185)

No. patients with associated systemic

diseases

Mean duration of hospital stay

FSD, days Total Airway obstruction No. deaths Parapharyngeal space Abscess 49 (26.5) 19 13.8F6.8 8 5 1 Cellulitis 22 (11.9) 2 6.3F2.4 0 0 0 Submandibular space Abscess 25 (13.5) 5 14.7F8.8 2 2 0 Cellulitis 4 (2.2) 0 7.5F2.0 0 0 0 Ludwig’s angina Abscess 11 (5.9) 5 19.9F11.3 3 3 0 Cellulitis 12 (6.5) 4 6.7F1.4 0 0 0 Extended space Abscess 14 (7.6) 10 20.7F7.0 9 5 1 Cellulitis 1 (0.5) 0 16 0 0 0 Parotid space Abscess 13 (7) 4 11.6F3.4 1 0 0 Retropharyngeal space Abscess 11 (5.9) 6 15.8F7.3 5 4 1

Posterior cervical space

Abscess 8 (4.3) 4 11.8F5.2 0 0 0

Anterior cervical space

Abscess 6 (3.2) 1 10.2F4.6 1 0 0 Carotid space Abscess 1 (0.5) 1 25 0 0 0 Cellulitis 3 (1.6) 1 9.3F4.4 1 0 0 Pretracheal space Abscess 2 (1.1) 0 12.0F1.0 0 0 0 Masticatory space Abscess 2 (1.1) 1 15F7 0 0 0 Prevertebral space Cellulitis 1 (0.5) 0 7 0 0 0 Total 185 (100) 63 13.0F7.0 30 19 3

diagnostic criteria of Ludwig’s angina are defined as the simultaneous involvement of the sublin-gual, submylohyoid, and submental spaces, either as abscesses or cellulitis. Clinically, most of them presented with apparent mouth floor swelling and double tongue signs. If two or more spaces were concurrently involved in a significant way, they were classified as extended spaces. The character of the infection, cellulitis, or abscess was confirmed by CT, needle aspiration, or surgery. Different spaces of deep neck infections were compared. Those patients with complications attributed to deep neck infections were analyzed.

RESULTS

Demography. Of 185 patients, 109 were men and

76 were women. Their ages ranged from 11 months to 88 years, with a mean age of 49.5 F 20.5 years. Among them, 95% were adults (176 of 185), 34.1% (63 of 185) were older than 60 years old, and 52.4% (97 of 185) were older than 50 years old. The age distribution curve peaked in the fifth decade (Figure 1). The number of patients with or without systemic diseases in each age group is shown separately in Figure 1.

Types of Deep Neck Infections (Space and Charac-ter). To identify the extent of infections and differentiate cellulitis from abscesses, a CT with contrast enhancement was performed on all

patients. Equivocal cases were further confirmed by needle aspiration, if applicable, or surgery. Abscess formation was noted in 142 patients (76.8%) and cellulitis in only 43 (23.2%). The distribution of the space and character is shown in Table 1. The parapharyngeal space was the most commonly involved space of deep neck infections (38.4%), followed by the submandibular space (15.7%), Ludwig’s angina (12.4%), extended space (8.1%), parotid space (7%), and retrophar-yngeal space (5.9%).

Etiology. The causes of deep neck infections were identified in 79 patients (43.7% of all pa-tients). Odontogenic infections were the most common cause (42 patients), which accounted for 52.2% (12 of 23) with Ludwig’s angina, 48.3% (14 of 29) with submandibular space infections, and 11.3% (eight of 71) with parapharyngeal space infections. Upper airway infection was the second most common cause (24 patients). They were usually related to parapharyngeal space infec-tions, accounting for 21.1% (15 of 71) of all para-pharyngeal space infections. The etiology of deep neck infections is recorded in Table 2.

Underlying Systemic Diseases. Sixty-three pa-tients (34.1%) had underlying systemic diseases; 38 were men, and 25 were women. Their ages ranged from 19 to 88 years, with a mean age of 57.4F16.7 years. There were 56 patients (88.8% of 63 cases) with diabetes mellitus (DM), six pa-tients (9.5%) with uremia or chronic renal insuffi-ciency, three patients (4.8%) with liver cirrhosis, two (2.4%) patients with myelodysplastic syn-drome, and one patient (1.2%) with gastric malig-nancy receiving chemotherapy treatment.

The most commonly involved space in these patients was the parapharyngeal space (33.3%); second was the extended space (15.9%), followed by Ludwig’s angina (14.3%) (Table 1). It is notable that up to 66.7% of patients (10 of 15) with an extended space abscess had associated systemic

Table 2.Etiology of deep neck infections.

Etiology

No. patients (%) (N= 185)

Odontogenic 42 (22.7)

Upper airway infection 24 (13)

Peritonsillar abscess 7 (3.8)

Foreign body (digestive tract) 2 (1.1) Surgery of aerodigestive tract 2 (1.1)

Skin infection 1 (0.5)

Parotitis 1 (0.5)

Unknown 106 (57.3)

Table 3.Comparison of patients with and without systemic diseases. No. patients Mean age FSD Mean duration of stayFSD, days No. complications (%) No.

tracheostomies (%) No. deaths

Systemic disease (+) 63 57.4F16.7 19.4F13.7 20 (31.7) 12 (19) 3

Systemic disease () 122 45.5F21.2 9.8F6.6 10 (8.2) 6 (4.9) 0

pvalues <.0001* <.0001* <.0001y <.05y <.05z

*Student’s t test.

yChi-square test.

diseases. The patients with underlying systemic diseases tended to have a higher mean age and longer duration of hospital stay, complications occurred more frequently, and they received more tracheostomies than those without underlying systemic diseases (Table 3).

Bacteriology. Results of pus cultures from either surgery or needle aspiration were available for 127 patients; 112 of those patients (88.2%) had bacterial growths (Table 4). The cultures of 40 (35.7%) of 112 patients were polymicrobial. The most common organisms were Streptococcus vir-idansand Klebsiella pneumoniae(33.9%, 33.9%), followed byPeptostreptococcus,h-hemolytic

strep-tococci, andNeisseriaspecies (17.0%, 8.9%, 8.9%). K. pneumoniaegrew in 56.1% of diabetic patients. Their distributions between DM and non-DM pa-tients were compared (Table 5).

Blood cultures were routinely checked for patients with systemic symptoms, such as fever or chills. Of the 71 available results, only 11 (15.5%) were positive.

Treatment. All patients received antimicrobial therapy. Of the abscess group (142 patients), 103 patients (72.5%) underwent surgical drainages (85 external, 13 internal, and five a combined ap-proach), 19 patients (13.4%) underwent repeated needle aspirations, one patient (0.7%) received a tooth extraction, and the other 19 patients (13.4%) only received intravenous antimicrobial therapy. Of the cellulitis group (43 patients), one patient (2.3%) underwent an external drainage, two pa-tients (4.7%) underwent Chiari’s incisions for peri-tonsillar abscesses, and the other 40 patients (93.0%) responded effectively to intravenous anti-microbial therapy. The intervals between

diagno-sis and operation ranged from 0 to 8 days, with a mean interval of 1.81F1.49 days.

All patients were discharged in stable condition, except for three deaths, which are described later.

Complications. Thirty patients (16.2%) had com-plications, and some individual patients had multi-ple complications (16 men and 14 women; mean age 60.7F 18.0). Except for one patient with carotid space cellulitis who had internal jugular vein thrombosis develop, all complications occurred in the abscess group. Patients with extended space abscesses, retropharyngeal space abscesses, and Ludwig’s angina abscesses experienced more fre-quent complications (64.3%, 45.5%, and 27.3%).

Nineteen patients (10.3%) had upper airway obstructions (11 men and eight women, mean age 66.6F12.4). Of them, 18 received tracheostomies. Those with extended space abscesses, retropha-ryngeal space abscesses, and Ludwig’s angina abscesses had upper airway obstructions develop more frequently (35.7%, 36.4%, and 27.3%). Three of the 19 patients died.

Table 6.Complications of deep neck infections.

Complication No. patients* (%) (N= 185) No. deaths* Airway obstruction 19 (10.3) 3 Upper gastrointestinal bleeding 6 (3.2) 2 Mediastinitis 5 (2.7) 2 Sepsis 4 (2.2) 3 Pneumonia 3 (1.6) 1 Skin defect 2 (1.1) 0 HHNK or DKA 2 (1.1) 1 IJV thrombosis 2 (1.1) 0 Facial palsy 1 (0.5) 0

Vocal cord palsy 1 (0.5) 0

Pleural effusion 1 (0.5) 0

DIC 1 (0.5) 1

Abbreviations: HHNK, hyperosmolar hyperglycemia nonketosis; DKA, diabetic ketoacidosis; IJV, internal jugular vein; DIC, disseminated intravascular coagulation.

*An individual patient may have multiple complications associated with death.

Table 5.Distribution of organisms in patients with and without diabetes mellitus.

No. patients (%) by organism

Patient group Klebsiella pneumoniae Streptococcus viridans Pepto-streptococcus DM (n= 41) 23 (56.1) 7 (17.1) 4 (9.8) Non-DM (n= 71) 15 (21.1) 31 (43.7) 15 (21.1)

Abbrevation: DM, diabetes mellitus.

Table 4.Most frequent organisms in pus culture.

Organism No. patients (%)*

Streptococcus viridans 38 (33.9) Klebsiella pneumoniae 38 (33.9) Peptostreptococcus 19 (17.0) h-hemolytic streptococci 10 (8.9) Neisseriaspecies 10 (8.9) Staphylococcus aureus 9 (8.0) Unidentified anaerobic bacteria 9 (8.0)

Candida 5 (4.5)

Coagulase-negative staphylococcus 4 (3.6)

Enterococcus 4 (3.6)

Eikenella 4 (3.6)

*Of 112 patients with positive cultures, the sum of total percentage exceeds 100 because of mixed infections.

Upper gastrointestinal bleeding occurred in six patients during admission; two patients died because of other concurrent complications.

Mediastinitis was noted in five patients (two extended space abscesses, one Ludwig’s angina abscess, and two retropharyngeal space absces-ses). Among them, three received surgical drain-age, and two received antimicrobial therapy. Two of the five died (mortality rate of 40%.)

Sepsis occurred in four patients; three of them died.

Pneumonia was noted in three patients, one of them died from subsequent sepsis.

DM-related complications developed in two patients, including one with hyperosmolar non-ketotic hyperglycemia and one with diabetic keto-acidosis. One patient died from pneumonia and sepsis. All the complications are shown in Table 6.

Mortality. There were three deaths (mortality

rate, 1.6%); the mean age of those who died was 76 years. All of them died of sepsis associated with systemic diseases, including DM in two patients.

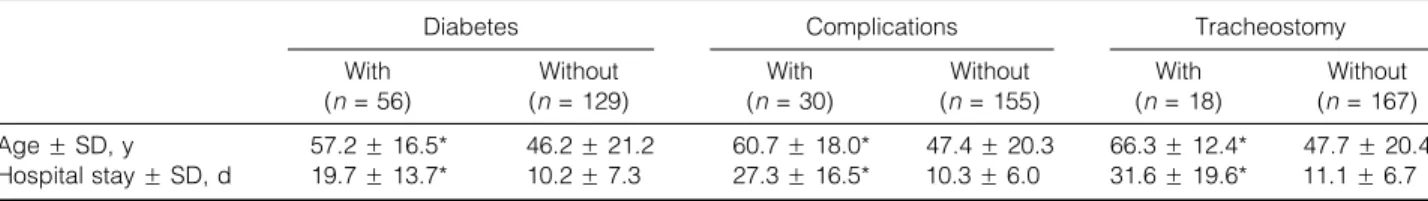

Duration of Hospital Stay. The duration of hospi-tal stay ranged from 2 to 78 days, with a mean stay of 13F7 days. The patients with DM (19.7F13.7 days), complications (27.3F16.5 days), and those who received tracheostomies (31.6 F 19.6 days) tended to have a longer hospital stay (Table 7).

DISCUSSION

From this study, we found that old age and as-sociated systemic diseases were the most impor-tant predisposing factors in deep neck infections. Those patients stayed in hospital longer, had complications more frequently, and had tra-cheostomies more often, and some even died. The differences between the compared groups were statistically significant. This difference may be because older patients with systemic diseases had lower defense pathogenic infections, their re-covery rate was low, which may have increased the number of complications, which in turn

pro-longed their hospital stay. The age distribution showed a relatively higher incidence between the fifth and eighth decades (Figure 1), differing from one recent report with 50% of the patients in their third or fourth decade.3This can be attributed to the progress of medical care and the increasing population of the older group. Another factor may be the lack of intravenous drug abuse or external blunt trauma in our series, which usually occurs in the young or middle aged.3

Odontogenic infection was the most common cause of deep neck infections in our study. This was consistent with the Parhiscar, Har-El, and Sethi reports.1 – 3The second most common cause of deep neck infection in their reports was intravenous drug abuse and trauma.1 – 3That differs from the upper airway infection in our series. The causes of infection remain obscure in 57.3% of patients, perhaps because the infectious foci had been resolved at the time of presentation.6Odontogenic infections usually spread continuously from the mandible or maxilla into the sublingual, subman-dibular, or masticatory spaces,7 accounting for 52.2% of Ludwig’s angina and 48.3% of subman-dibular space infection in our series. Both odonto-genic infections and upper airway infections can lead to cervical lymphadenitis and subsequent abscess formation. Moreover, infections of the peritonsillar, submandibular, masticatory, and parotid space can spread directly into the para-pharyngeal space. These factors explain why the parapharyngeal space was affected most fre-quently in our study.

The bacteriologic pattern of deep neck infec-tions is usually polymicrobial, including aerobes, microaerophilics, and anaerobes. According to recent reports, most common organisms seem to be aerobic S. viridans, h-hemolytic streptococci,

Staphylococcus, K. pneumoniae, anaerobic Bac-teroides, and Peptostreptococcus.1,3,6,8 In our study, 35.7% of the positive pus cultures were polymicrobial. S. viridans is one of the most commonly isolated organisms, consistent with previous reports,1,3 and can be explained by the high rate of odontogenic infections.K. pneumoniae

Table 7.Comparison between different groups of patients.

Diabetes Complications Tracheostomy

With (n= 56) Without (n= 129) With (n= 30) Without (n= 155) With (n= 18) Without (n= 167) AgeFSD, y 57.2F16.5* 46.2F21.2 60.7F18.0* 47.4F20.3 66.3F12.4* 47.7F20.4 Hospital stayFSD, d 19.7F13.7* 10.2F7.3 27.3F16.5* 10.3F6.0 31.6F19.6* 11.1F6.7 *Student’s t test, p < .001.

is another common isolated organism, which is also attributed to the high incidence of pus cul-ture rate (56.1%) in the patients with DM. From the review of articles in Taiwan and Singapore,

K. pneumoniae was the most common causative

pathogen in patients with DM.8,9 The results help us to choose an appropriate antimicrobial agent in patients with DM. Similar to previous reports,1 gram-negative aerobic organisms other than the K. pneumoniae and Neisseria species played a limited role in our series. The inabil-ity to culture an organism in 11.8% of the pus samples may result from the liberal use of anti-biotics before admission and the high dose of in-travenous antibiotics before surgical drainage of the abscess.8

Blood culture is a routine laboratory test in acute febrile illness, but our results revealed a low positive culture rate (15.5%). Har-El et al1 also reported a low positive rate of blood culture, so the results of blood culture were assumed to have little impact on the management of deep neck abscesses compared with pus culture.

All patients with suspected deep neck infec-tions had contrast-enhanced CT performed to identify the extent of the infections and differ-entiate cellulitis from abscesses. CT helps to decide whether surgical intervention is indicated. CT does not always accurately differentiate abscesses from cellulitis.10,11Equivocal cases are further confirmed by needle aspiration if appli-cable or as a last result through surgery.

The treatment of deep neck infection consists of securing the airways, using antimicrobial the-rapy, and surgical drainage of the abscesses. Early open surgical drainage remains the most appropriate method of treating a deep neck abscess. The therapeutic use of needle aspiration has been suggested in selective cases.12 Success-ful conservative medical treatment was also pointed out in 90.32% (28 of 31) by Mayor et al.13 Our experience prefers surgical drainage in patients with significant abscess formation seen on CT, impending complications, or poor response to previous antimicrobial therapy. If there is a small amount of abscess and no impending complications are noted, conservative manage-ment may be tried. In the treatmanage-ment of deep neck infections of patients with DM, control of their diabetes is important in the control of their infection.9 In our series, all patients with DM received oral hypoglycemic agents or insulin to keep their blood sugar strictly <200 mg/dL. Most of them had good results.

Deep neck infections may result in life-threat-ening complications, such as upper airway ob-struction, descending mediastinitis, jugular vein thrombosis, venous septic emboli, carotid artery rupture, adult respiratory distress syndrome, septic shock, and disseminated intravascular coa-gulopathy.14 – 16In our series, the most frequently occurring complication was upper airway obstruc-tion. Although the parapharyngeal space abscess is the one most frequently involved space in deep neck infections, the extended space abscess, retro-pharyngeal space abscess, and Ludwig’s angina abscess had a higher incidence of inducing upper airway obstruction (35.7%, 36.4%, and 27.3%). Parhiscar and Har-El also reported a higher incidence of tracheostomies in Ludwig’s angina abscesses (75%) and retropharyngeal space ab-scesses (25%).3It is understandable that anatomic factors cause obstruction of the upper airway more frequently in retropharyngeal space and Ludwig’s angina abscesses. Extended space infections often indicate a severe form of deep neck infections, explaining why upper airway obstructions devel-oped in 35.7% of such infections in our series. The incidence of upper airway obstruction in Ludwig’s angina abscesses was much lower than in Parhis-car and Har-El’s report, probably because many of the patients were treated in the early stage of the disease. In the study, five patients had mediastinitis develop. Two of them died, for a mor-tality rate of 40%. This is similar to Estrera’s re-ports (42%).14

DM was the most common associated systemic disease (88.9%); the same was found in Parhiscar’s report (50%)3 and Sethi’s study (80%).8 DM re-sulted in a defect in the host’s immune function such as cellular immunity complement activa-tion17and polymorphonuclear neutrophil function and that increased the risk of vascular complica-tions and the episodes of infection.18 There were three deaths in our series. All of them had associated systemic diseases, were older than 72 years, and two of them had DM. Therefore, when dealing with deep neck infections, more attention should be paid to patients with DM or other associated systemic diseases.9,16

In general, the abscess group was more fre-quently associated with systemic diseases and had more complications (including tracheostomies) than the cellulitis group. These data provide us with a good guide about the course of deep neck infections in the future, but the severity of the infections of different patients with the same type of deep neck infections may vary significantly.

CONCLUSION

The results of this research of 185 patients with deep neck infections support the following conclusions: 1. It is essential to pay attention to the high-risk

group (old age, DM, underlying systemic dis-ease), because they can often progress to life-threatening conditions.

2. The high prevalence rate of DM (30.3%) indicates that DM may be a precipitating factor in deep neck infections.

3. S. viridans, K. pneumoniae, and Peptostrepto-coccus were three leading organisms in our study. Antibiotics should coverK. pneumoniae in patients with DM.

4. Early surgical drainage remains the main method of treating deep neck abscesses. Ther-apeutic needle aspiration and conservative medical treatment are effective in selective cases that have minimal abscess formation and are stable.

5. In the extended space abscess, retropharyng-eal space abscess, and Ludwig’s angina, we should pay more attention to the prevention of airway obstruction.

REFERENCES

1. Har-El G, Aroesty JH, Shaha A, Lucente FE. Changing trends in deep neck abscess. A retrospective study of 110 patients. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1994;77:446 – 450. 2. Sethi DS, Stanley RE. Deep neck abscesses—changing

trends. J Laryngol Otol 1994;108:138 – 143.

3. Parhiscar A, Har-El G. Deep neck abscess: a retrospective review of 210 cases. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 2001;110: 1051 – 1054.

4. Marra S, Hotaling AJ. Deep neck infections. Am J Otolaryngol 1996;17:287 – 298.

5. Scott BA, Stiernberg CM, Driscoll BP. Infections of the deep spaces of the neck. In: Bailey BJ, editor. Head and neck surgery – otolaryngology, 3rd ed. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott; 2001. p 701 – 715.

6. El-Sayed Y, Al Dousary S. Deep-neck space abscesses. J Otolaryngol 1996;25:227 – 233.

7. Yonetsu K, Izumi M, Nakamura T. Deep facial infections of odontogenic origin: CT assessment of pathways of space involvement. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1998;19: 123 – 128.

8. Sethi DS, Stanley RE. Parapharyngeal abscesses. J Laryn-gol Otol 1991;105:1025 – 1030.

9. Chen MK, Wen YS, Chang CC, Lee HS, Huang MT, Hsiao HC. Deep neck infections in diabetic patients. Am J Otolaryngol 2000;21:169 – 173.

10. Miller WD, Furst IM, Sandor GK, Keller MA. A prospec-tive, blinded comparison of clinical examination and computed tomography in deep neck infections. Laryngo-scope 1999;109:1873 – 1879.

11. Lazor JB, Cunningham MJ, Eavey RD, Weber AL. Comparison of computed tomography and surgical find-ings in deep neck infections. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1994;111:746 – 750.

12. Herzon FS. Needle aspiration of nonperitonsillar head and neck abscessed. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1988; 11:975 – 982.

13. Plaza Mayor G, Martinez-San Millan J, Martinez-Vidal A. Is conservative treatment of deep neck space infections appropriate? Head Neck 2001;23:126 – 133.

14. Estrera AS, Landay MJ, Grisham JM, Sinn DP, Platt MR. Descending necrotizing mediastinitis. Surg Gynecol Ob-stet 1983;157:545 – 552.

15. Beck HJ, Salassa JR, McCaffrey TV, Hermans PE. Life-threatening soft tissue infections of the neck. Laryngo-scope 1984;94:354 – 362.

16. Chen MK, Wen YS, Chang CC, Huang MT, Hsiao HC. Predisposing factors of life-threatening deep neck infec-tion: logistic regression analysis of 214 cases. J Otolar-yngol 1998;27:141 – 144.

17. Hostetter MK. Handicaps to host defenses: effects of hypoglycemia on C3 and Candida albicans. Diabetes 1990;39:271 – 275.

18. Delamaire M, Maugendre D, Moreno M, et al. Impaired leukocyte functions in diabetic patients. Diabetic Med 1997;14:29 – 34.