FISCAL EFFECTS OF POLITICAL

DECENTRALIZATION

Primož Pevcin

University of Ljubljana Faculty of Administration Gosarjeva ulica 5 1000 Ljubljana Slovenia e-mail: primoz.pevcin@fu.uni-lj.si telephone: +38615805584Abstract

Political decentralization, as a tool for achieving greater efficiency of public sector, is much debated issue in the vast majority of democratic countries. Therefore, the purpose of the paper is to discuss economic and fiscal effects of political decentralization. Namely, political decentralization causes greater allocative efficiency of governmental decision making but on the other hand can cause technical inefficiency, such as, for instance, lost economies of scale or the increased inbuilt pressures on government finances. Besides, the purpose of the paper is also to empirically verify the effect of decentralization on the size of government spending in the sample of 77 democratic countries. The results of the empirical analysis presented in the paper suggest that political decentralization obviously inflates government transfer spending, thereby reinforcing the idea that decentralization causes flypaper effect and increased government spending, in a sense corroborating collusion and fiscal illusion hypotheses on the fiscal implications of political decentralization.

Keywords: political institutions, decentralization; government spending; democratic

countries

JEL codes: H77; H50

1.

Introduction

Nowadays, a wide variation in the size of government and in the scope of its activities across countries could be observed.1 Literature has pointed out several groups of explanations for this phenomenon, ranging from economic, social, political, and cultural to demographic ones.2 More recently, one of the explanations of this variation focused on the effect of

1 For instance, when observing developed countries, the overall size of government, measured with the share of total general government spending in GDP, can range from around 20 % in some eastern Asian countries to above 50 % in some Nordic Countries in recent years (see Pevcin, 2004).

2 On the discussion about literature and the empirical examination of the effect of various economic, social, cultural and demographic factors on the size of government spending see Pevcin (2004).

different aspects of political institutions on government policy. The theory, so-called economics of comparative politics, focused on the fiscal implications of political regimes and electoral rules and was, for instance, influentially exposed by Persson et.all. (1998). Namely, the vast majority of democratic countries are representative democracies, which, unless the preferences of the voters and the elected politicians are completely aligned, according to Persson and Tabellini (1999) creates a principal-agent problem between the voters and their elected representatives. The aim of the repeated elections is to make elected politicians accountable to the electorate as the elections allow voters to choose their most preferred candidate, but they can also be disciplining device, since voters are also able to control ruling politician’s performance. For example, Ferejohn (1986) argues that a major role of repeated elections is to create incentives for politicians to act in the interest of voters rather than to select the most preferred policy proposal.

However, a politician’s desire to win the next elections can sometimes lead his considerations in choosing policy. There are several empirical studies that find the support for this opportunistic electoral behavior of politicians in the form of the manipulation of the economy in order to improve electoral prospects.3 Namely, politicians must use appropriate policy instruments, for example monetary, fiscal, income policy etc., in order to achieve their objectives. In fact, according to Drazen (2000), the strongest evidence for opportunistic electoral behavior of politicians is to be found in the use of fiscal policy instruments, especially in the use of transfers and subsidies.

In this context, it is evident that the elections cause opportunistic electoral behavior of politicians, who want to be re-elected. Intuitively, it can be concluded that the properties of political institutions4 will determine the type of opportunistic behavior of politicians and the selection of the most appropriate instruments of fiscal policy to achieve their objectives. The selection of fiscal policy instruments can be observed in the size and composition of government spending. Therefore, the purpose of the paper is to theoretically and empirically investigate the relationship between the size of government spending and the third dimension of political institutions, the structure of government, which describes political centralization or decentralization of a country, in a set of democratic countries.

3 More on this issue see Nordhaus (1975) or Tufte (1978).

4 In this context, besides electoral rule and regime type, a third dimension of political system could also be added, that is the structure of government, denoting the fact if decision-making and operation of government is also decentralized.

2.

Economic and political effects of decentralization

Decentralization is contemporary a hot political issue in the vast majority of developed countries, as greater decentralization should help achieving greater efficiency of government. Nevertheless, political decentralization, that is the allocation of some control rights and political decision-making to lower levels of government, should also affect government spending. Namely, Seabright (1996) stresses that decentralization increases the probability that the welfare of a given region is decisive for re-election of politicians, which increases their accountability and strengthens the voters’ electoral control. It is worth noting that decentralization has economic and political effects, which both result in selected fiscal policy. In connection to economic effects, Bailey (1999) argues, in accordance to Oates’ decentralization theorem, that the creation of sub-national governments leads to a welfare gain through improved allocative efficiency, but centralization should have advantages in increased technical efficiency and economies of scale, which should emerge due to the production in large numbers.5 Improved allocative efficiency of decentralized governmental decision making can also be observed in its informational advantage concerning production costs of public goods. Namely, the smaller is the size of local jurisdiction, the more precise should be the information about production costs due to the so-called geographical proximity effect, which causes decreases in the variance of marginal costs. In contrast, increased technical efficiency of centralized governmental decision making can also be observed in potential advantages to internalize spill-over effects and spatial externalities of (local) public goods (Gilbert and Picard, 1996).6

Besides economic advantages and disadvantages, decentralization has also political ones. Decentralization improves the electoral control of voters, and more importantly, in a federation voters can evaluate the relative performance of policies in different regions. By using voting strategies that depend on the relative performance rather than on a cut-off level of utility, voters can prevent politicians from abusing political power. If elections are held in different regions, voters are able to reduce political rents by using retrospective voting strategies (Wrede, 2001). On the contrary, the main political disadvantages of the

5 The economies of scale are particularly relevant for infrastructure intensive activities, such as for example water and sewerage (Fox and Gurley, 2006).

6 This trade-off between informational advantages over production costs and spill-over effects of public goods implies that some optimal size of jurisdictions, intermediate between perfect centralization and perfect decentralization, exists. Namely, the more precise the information on production costs of public goods is, the more centralized governmental decision making should be. Inversely, the more precise the information on spill-over effects of public goods is, the more decentralized gspill-overnmental decision making should be (more on this see Gilbert and Picard, 1996).

decentralized (federal) political system are that it can generate flypaper effects7 (Brennan and Pincus, 1996) and increased governmental redistribution policies8 (Borck, 2002).

The cumulative effect of decentralization on the level of government spending should depend on the fact, whether allocative efficiency outweighs the technical inefficiencies and diseconomies of scale and whether decreased rents of politicians outweigh the increased local spending due to the flypaper effect. In this context, several main hypotheses can be put forward on the relationship between political decentralization and government size (de Mello, 1999):

1. Decentralization should increase the size of local government. The idea is that the emphasis on local government provision may put pressure on these governments to increase spending and take on a wider range of expenditure functions and fiscal responsibilities, thereby leading to higher spending levels. Namely, local preferences and needs are usually best met by local rather than central governments, which are “closer” to the voters. Subsequently, better knowledge of local needs and preferences may increase the demand for local government provision. Nevertheless, according to this hypothesis, it is expected that increase in local government spending is likely to occur simultaneously with the fall in central government spending.

2. Decentralization should reduce the overall size of government (so called decentralization hypothesis). According to this hypothesis, greater autonomy in policymaking also demands autonomy to set taxes. However, local government spending and taxing powers are likely to be constrained by factor mobility. In this case, competition between local governments for mobile taxpayers and other economic resources is likely to constrain their taxing powers, encourage a more cost-efficient provision of local public goods and services, and therefore restrain the overall size of government. Nonetheless, because central government spending is also likely to fall as a result of the delegation of spending functions to local governments, total government spending should fall according to this hypothesis.

7 The flypaper effect refers to the fact that lump-sum transfers paid to a local community have a greater effect on local government spending than the equivalent increase in private income. This means that additional money tends to remain in the sector into which it is paid, or in other words transfer money should stick where it hits (more on this see Strumpf, 1998).

8 Namely, political decentralization causes increased political participation, because individuals’ chances of influencing political outcomes are increased. It can be assumed that political participation (i.e., voting) is a normal good (demand increases with individual’s income), indicating that increased political participation would cause decisive voter to be poorer than in centralized system, thereby demanding greater social programs that redistribute income and wealth. This should lead to the increased size of government (more on this see Borck, 2002).

3. Decentralization should encourage collusive behavior among local governments and increase the size of local government (so-called collusion hypothesis). In accordance with this hypothesis, if decentralization does not foster competition among local governments, local expenditure may even increase because local governments may collude among themselves (and with the central government) and finance local expenditures through revenue sharing. Namely, through collusion, local governments are able to increase their total revenues and spending beyond the level that would otherwise be attained in a competitive environment. Besides, when emphasis is placed on revenue sharing to finance local government spending, local governments may face an incentive to under-utilize their own tax bases at the expense of national sharable revenues.9 Namely, the burden of providing public goods and services can be shared across different local units, whereas the benefits of public sector spending can be internalized and generate a political payoff to certain local government. Consequently, by sharing the burden of provision with other local units, revenue sharing reduces the perceived tax price of local services, allowing local governments to increase spending above levels otherwise tolerated by voters (also so-called fiscal illusion hypothesis).10

3.

Empirical analysis – data and methodology description

The purpose of the paper is also to empirically verify the effect of political decentralization on government spending in the sample of 77 democratic countries. 11 Therefore, cross-section modeling is used in order to focus upon international comparison in the effect of political decentralization on the size of government spending. The share of government transfers and subsidies as percentage of gross domestic product (TRF) is used as dependent variable measuring the size of government. Besides the variable describing the existence of political decentralization in country (FED), some additional relevant explanatory (control) variables, based on political economy of government spending, are used in econometric model:

1. Real gross domestic product per capita (GDPC), urbanization rate (URB) and the share of population above 65 years (OLD) or below 19 years (YOU). According to Wagner’s

9 See also Inman and Rubinfeld (1996).

10 In other words, in this case decentralization itself creates flypaper effects. Besides, in the context of revenue

sharing, Baqir (1996) argues that government overspending bias arise from districting – the greater the number of districts (local units), the greater is the overspending bias and size of government. Moreover, he argues that forms of government with strong executives break the link between districting and government size, meaning that they are more effective in curtailing the spending bias.

11 Sample consists of 36 European countries, 13 African countries, 18 American countries and 10 Asian/Oceanic

hypothesis, government spending both absolutely and relatively expands as economies develop. Therefore it is to be expected that the level of GDP per capita would positively affect the variations in the size of government spending. Besides, the share of population living in urban areas should positively affect the size of government spending, since urbanization is likely to facilitate increased pressures on government services such as police, infrastructure etc. Similarly, economic theory recognizes the importance and side effects of population aging. This, according to Holsey and Borcherding (1997), involves increased demand for government spending on health care, social security, etc. Moreover, a high dependency ratio in the form of a large share of young population should for example increase demand for government spending on education, so it is to be expected that both variables should positively affect government spending.

2. Country size (POP) and trade openness (OPN). Alesina and Warcziarg (1998) argue that government spending correlates negatively with country size, whereas Rodrik (1998) finds positive correlation between government size and trade openness.

3. Country’s political regime (PRES) and electoral rule (PLUR). According to the theory, it should be expected that presidential political regime should negatively affect the size of government spending, whereas the presence of plurality in electoral rules should, in particular, negatively affect government transfer spending (Persson, 2001).

4. Share of largest ethno-religious group in total population (FRAGM). This variable indicates the level of ethno-religious homogeneity of society. However, the existing literature points out two countervailing effects on government spending. On the one hand, it should negatively affect government spending through political instability channel. Namely, in more heterogeneous societies government spending to different groups within society should serve as a means of increasing the political stability of a country, meaning that spending through this ”channel” should be minimized in more homogeneous countries (Annett, 2000). In contrast, Alesina et.all. (2001) argue that homogeneity of society should positively affect government spending, since in more homogeneous societies voters are likely to approve increased spending to certain social groups, because it is larger probability that they do not belong to certain ethno-religious minority. Nonetheless, it is clear that the inclusion of this variable is appropriate only in the sample of democratic countries, where various social groups have possibility to express their demands in political process.

5. Dichotomous dummy variables for Asian countries (ASIA), Western-European countries (WEU) and countries in transition (TRA). The purpose of the inclusion of these

variables in the econometric model is to identify possible cultural or institutional differences that would imply different average size of government in these “regions”. Namely, it is to be expected that Asian countries would have smaller size of government spending because of their cultural values, which promote family background. On the contrary, it is expected that Western-European industrialized countries would have larger governments because of the incorporated ”sociality” and ”individualism” that both promote large role of government, even in the manner of replacing the traditional family. The purpose of inclusion of separate variable for transitional countries is to identify possible effects of the change in economic system, which largely reduced the role of government. It is to be expected that remnants of past regime would cause the larger government in those countries.

Table 1: Variable description and data sources12

Variable Description Data source

TRF General government transfers and subsidies (% GDP) Gwartney and Lawson (2002)

FED Structure of government, dichotomous dummy variable, 1 – existence of political decentralization

Beck et.al. (2001)

GDPC Real gross domestic product per capita (in USD) World Development Indicators (2001)

OPN Trade openness (sum of the share of imports and exports in % of GDP)

World Development Indicators (2002)

POP Country size (population of the country in millions) World Development Indicators (2002)

OLD Share of population older than 65 years in total population (%)

U.S. Census (2001)

YOU Share of population younger than 19 years in total population (%)

U.S. Census (2001)

URB Urbanization rate of a country (share of urban population in % of total population)

World Development Indicators (2002)

PRES Political regime, dichotomous dummy variable, 1 – presidential political regime

Beck et.all. (2001)

PLUR Electoral rules, dichotomous dummy variable, 1 – existence of plurality in electoral rules

Elections around the world (2003)

FRAGM Fragmentation (homogeneity) of society (share of largest ethno-religious group as % of total population)

Encarta Encyclopedia (2003)

4.

Results and discussion

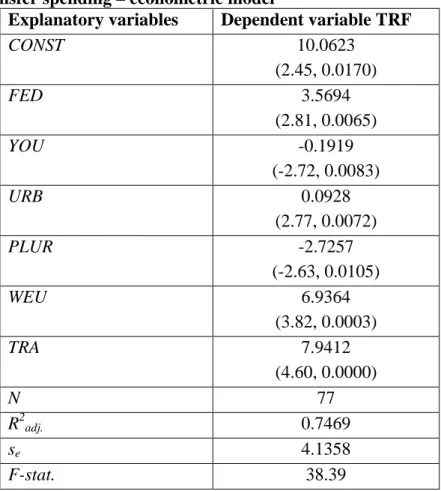

Following, the results of the empirical econometric analysis are presented in table 2.

Table 2: The effect of political decentralization and other socioeconomic variables on government transfer spending – econometric model13

Explanatory variables Dependent variable TRF

CONST 10.0623 (2.45, 0.0170) FED 3.5694 (2.81, 0.0065) YOU -0.1919 (-2.72, 0.0083) URB 0.0928 (2.77, 0.0072) PLUR -2.7257 (-2.63, 0.0105) WEU 6.9364 (3.82, 0.0003) TRA 7.9412 (4.60, 0.0000) N 77 R2adj. 0.7469 se 4.1358 F-stat. 38.39

Source: Author’s calculation

The results of the analysis presented in the table above indicate that almost 75 percent of variation in differences in the size of government transfer spending across countries can be explained with only six statistically significant explanatory variables.14 Besides, the results also indicate several interesting points:

First, politically decentralized countries should have larger shares of transfers and subsidies in GDP. This supports the common fable that more democracy obviously demands and creates more government activities. In addition, this finding supports the idea of Brennan and Pincus (1996) that a federal system can itself generate flypaper effects, meaning that lump-sum government grants boosts local expenditure more than an equivalent increase in

13 Calculations have been obtained by using Eviews software. Only statistically significant variables (at 95 % margin) are presented. Values of t-statistics and p-values are presented in parentheses. Due to the presence of heteroscedasticity, ordinary least square estimation is corrected with White's heteroscedasticity-consistent covariance matrix.

14 This is not a bad result, especially if it is taken into account that cross-sectional data are used. Namely, in this case, lower values of the coefficient of determination are typically obtained due to the diversity of the units in the sample. Consequently, the stress should be on the logical and theoretical relevance of the explanatory variables and their statistical significance (see Gujarati, 2002). Nevertheless, the obtained overall results of the estimated regression model should be technically acceptable, since F value of the regression is highly

private income, because grant money sticks where it hits. Consequently, government spending increases. Besides, the results also indicate that decentralization obviously causes increased government spending due to increased political participation. Nevertheless, this should also indicate, in more technical terms, that larger technical inefficiencies probably outweigh larger allocative efficiencies of decentralized governmental decision making.

Second, countries with larger share of population below 19 should have smaller transfers and subsidies in GDP. This is quite opposite to the theoretical predictions of positive effects, since young population is in large part treated as dependent population.

Third, countries with larger share of urban population in total population have larger transfer spending. Several possible explanations exist about this relationship. Namely, it is possible that larger urbanization rate is associated with the higher level of economic development, which implies also pressures on government spending. Alternatively, it is possible that in urban cities family ties are looser; meaning that government with its transfer spending replaces the traditional family.

Fourth, countries with plurality electoral rule have smaller transfers and subsidies in GDP. This is in line with theoretical predictions that plurality in elections causes smaller pressures on public transfers and subsidies due to the properties of electoral competition.

Fifth, dummy variables indicating regional differences show that, on average, Western European and transitional economies have larger share of transfers and subsidies in GDP. This is in line with predictions of greater reliance on government for providing social security in European countries. However, it seems that on average transitional economies have larger transfers and subsidies in part due to the vast social problems created by the change of political and economic system and in part due to the still-existing remnants of former all-encompassing socialist state.

5.

Conclusion

The results of the empirical analysis, presented in the paper, suggest that political decentralization, a dimension of political system, is associated with larger share of transfers and subsidies in GDP, thereby reinforcing the idea that a decentralized political decision making system itself causes flypaper effect and increased government spending, in a sense corroborating collusion and fiscal illusion hypothesis. Nevertheless, the explanation if larger government spending caused by decentralization is good or bad from voters’ perspective depends on the fact whether marginal social costs of additional spending equal the marginal

social benefit, yet modern concepts of public sector reform are in favor of smaller size of government spending. Nonetheless, the obtained results also indicate that the existence of plurality in electoral rules negatively affect government spending. In this context, it should be noted that possibility exists, especially in the case of smaller countries, to combine relatively centralized government with plurality in electoral rules, which should enable greater representation of local interests in the parliament without the need to establish some kind of local jurisdictions. This could also have favorable (negative) effects on the size of government spending.

References

[1] ALESINA, A. et.all. Why Doesn’t the US Have a European-Style Welfare System?.

(NBER Working Paper No. 8524). Cambridge (MA): National Bureau of Economic

Research, 2001.

[2] ALESINA, A., WACZIARG, R. Openness, Country Size and the Government. Journal

of Public Economics, 1998, vol. 69, pp. 305-321.

[3] ANNETT, A. Social Fractionalization, Political Instability, and the Size of

Government. (IMF Working Paper 00/82). Washington: International Monetary Fund,

2000.

[4] BAILEY, S. J. Local Government Economics. Basingstoke: Macmillan Press, 1999. ISBN 0-333-66908-8.

[5] BAQIR, R. Districting and Government Overspending. (IMF Working Paper 01/96). Washington: International Monetary Fund, 1996.

[6] BECK, T., et all. New Tools and New Tests in Comparative Political Economy: The Database of Political Institutions. World Bank Economic Review. 2001, vol. 15, no. 1, pp. 165-176.

[7] BORCK, R. Jurisdiction size, political participation, and the allocation of resources.

Public Choice. 2002, vol. 113, pp. 251-263.

[8] BRENNAN, G., PINCUS, J.J. A minimalist model of federal grants and flypaper effects. Journal of Public Economics. 1996, vol. 61, no. 2, pp. 229-246.

[9] DE MELLO, L. Fiscal Federalism and Government Size in Transition Economies: The

Case of Moldova. (IMF Working Paper 99/176). Washington: International Monetary

Fund, 1999.

[10]DRAZEN, A. Political Economy in Macroeconomics. New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2000. ISBN 0-691-09257-5.

[11]ELECTION WORLD. Elections around the World 2003. Access from:

<http://electionworld.org/election>.

[12]ENCARTA ENCYCLOPEDIA. Dublin: Microsoft, 2003.

[13]FEREJOHN, J. Incumbent performance and electoral control. Public Choice. 1986, vol. 50, pp. 5-26.

[14]FOX, W., GURLEY, T. Will Consolidation Improve Sub-National Governments?.

(Working Paper 3913). Washington: World Bank, 2006.

[15]GILBERT, G., PICARD, P. Incentives and optimal size of local jurisdictions.

European Economic Review. 1996, vol. 40, pp. 19-41.

[16]GWARTNEY, J., LAWSON, R. Economic Freedom of the World: 2002 Annual

Report. Vancouver: Fraser Institute, 2002.

[17]GUJARATI, D.N. Basic Econometrics. Fourth Edition. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2002. ISBN 0-07-112342-3.

[18]HOLSEY C.M., BORCHERDING T.E.: Why Does Government’s Share of National Income Grow?. In: MUELLER D.C. (ed.). Perspectives on Public Choice: A

Handbook. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1997. ISBN 0-521-55654-6.

[19]INMAN, R.P., RUBINFELD, D.L. Designing Tax Policy in Federalist Economies: an Overview. Journal of Public Economics. 1996, vol. 60, pp. 307-334.

[20]NORDHAUS, W.D. The Political Business Cycle. The Review of Economic Studies. 1975, vol. 42, no. 2, pp. 169-190.

[21]PERSSON, T. Do Political Institutions Shape Economic Policy?. (NBER Working

Paper 8214). Cambridge (MA): National Bureau of Economic Research, 2001.

[22]PERSSON, T. et.all. Toward micropolitical foundations of public finance. European

Economic Review. 1998, vol. 42, no. 3-5, pp. 685-694.

[23]PERSSON, T., TABELLINI, G. The Size and Scope of Government: Comparative Politics with Rational Politicians. European Economic Review. 1999, vol. 43, no. 4-6, pp. 699-735.

[24]PEVCIN, P. Cross-country differences in government sector activities. Zbornik radova

[25]RODRIK, D. Why do more open economies have bigger governments?. Journal of

Political Economy. 1998, vol. 106, no. 5, pp. 997-1032.

[26]SEABRIGHT, P. Accountability and decentralisation in government: an incomplete contracts model. European Economic Review. 1996, vol. 40, no. 1, pp. 61-89. [27]STRUMPF, K.S. A predictive index for the flypaper effect. Journal of Public

Economics. 1998, vol. 69, no. 3, pp. 389-412.

[28]TUFTE, E. Political Control of the Economy. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1978. ISBN 0-691-07594-8.

[29]WORLD DEVELOPMENT INDICATORS 2001. Washington: World Bank, 2001. [30]WORLD DEVELOPMENT INDICATORS 2002. Washington: World Bank, 2002. [31]WREDE, M. Yardstick competition to tame the Leviathan. European Journal of