* Benjamin R. Hoetzel is Research Fellow at the University of Applied Sciences Heilbronn in Germany. His

Working Paper

Change Management within ERP Projects

Benjamin R. Hoetzel

*University of Applied Sciences Heilbronn, Germany

Abstract

Radical and incremental changes within an ERP project are essential for the success of the implementation. Although the success factors of such projects have been widely discussed, ERP projects still fail. Therefore, the paper critically discusses ERP-enabled change manage-ment, its critical success factors and best-practice management methods. Furthermore it iden-tifies several situations which are decisive for the occurrence of resistance to changes and suggests steps to overcome this resistance. The theoretical discussion is supported by a practi-cal ERP project within a small-sized company.

Copyright © 2005, Benjamin R. Hoetzel, University of Applied Sciences Heilbronn, Germany

Introduction

In today’s economy with its dynamic and fast moving markets, most companies seek to integrate Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) systems as a contributing factor to maintain their ability to compete. In this process the companies are disposing of their antiquated legacy systems and replace them through ERPs.

ERPs are an integrated set of applications which support organisational activities such as finance and accounting, sales, pro-duction, and logistics. Furthermore they can be seen as optimisation and integration

tools of business processes across the or-ganisational supply chain. Moreover, ERPs are beneficial because they are integrated instead of fragmented, embed best business practices within software routines, and provide organisational members with di-rect access to real-time information (Ross 1999). Although ERPs provide benefits such as: improving the effectiveness and efficiency of the corporate IT infrastructure or enabling the integration of global busi-ness processes, many ERP projects fail (Aladwani 2001; Robey et al. 2002). Al-Mashari and Zairi (2000a) report on failure which occurs due to the employees’

resis-tance to change. Many companies ignore that ERP implementation represents more than an incremental change. Moreover, it is a radical change of technical infrastructure, business processes, organisational struc-ture, the roles and skills of organisational members, and knowledge management activities. All the changes in these areas are essential for the success of the imple-mentation (Martin 1998; Davenport 1998). This paper analyses the importance of change management in an ERP implemen-tation project. It describes an implementa-tion at a small sized German manufactur-ing company named WZM Werkzeug-maschinen GmbH (pseudonym name). The company is a classic SME (small- and me-dium-sized enterprise) producing tools for presses in the automotive sector. It em-ploys 120 people at two production sites in Germany.

The paper first identifies the factors which initiate a resistance to change within the organisation and discusses the need for quickly adopting to changes which are enabled by ERP implementations. Subse-quent, critical success factors – which are an essence of ERP projects and decisive for managing change – are identified and their importance will be critically re-viewed. Furthermore we will focus on the change management aspect within such projects and critically discuss the impact on the employees and the organisation as a

whole. At last, a summary will pick up the core findings in this paper.

ERP-Implementation – factors initiating a resistance to change

In 2004, WZM Werkzeugmaschinen GmbH faced new challenges driven by the growth of the company and the set-up of a second plant. The company also received a stronger demand for its products and ser-vices which created additional pressure to expand its production. As it had not been necessary yet, WZM Werkzeugmaschinen GmbH did not use any IT-support for the management of its company. But the growth also demanded for an implementa-tion of a new ERP system in order to not lose control over the processes, and to re-duce costs. WZM Werkzeugmaschinen GmbH also recognized that it is not enough to change the IT system but also to adapt the processes, to change workplace defini-tions, and to familiarize the employees with the ERP system.

However the implementation of an ERP system often results in a need for Business Process Re-Engineering (BPR) in parallel (Al-Mashari and Zairi 2000; Al-Mashari 2003). WZM Werkzeugmaschinen GmbH realised quickly that forcing the ERP to match existing business processes meant a big effort in customising the solution. Fur-thermore the customising of an ERP

sys-tem is a continuous process which affects not only processes but also hierarchies and functional divisions. This is a major issue for the organisation and easily creates a climate of perpetual change among the employees.

In the literature, Leana and Barry (2000) comment that organisations and employees increasingly are willing to change their work, and the procedures. On the other hand they are looking to reduce uncertainty and seek for stability. Caruth et al. (1985) found several factors, why people usually are resistant to change. Resistance occurs especially when change: stands for a per-ceived lower status or prestige, reduces authority or freedom, causes fear, disrupts established work routines, affects job con-tent, rearranges formal and informal group relationships, is forced upon employees without explanation, or because of mental and physical lethargy (Caruth et al. 1985). Exploring the organisational change litera-ture more in depth, the work of Kotter and Schlesinger (1979, pp. 107-108) diagnosed four factors for resistance to change: paro-chial self-interest, misunderstanding and lack of trust, different assessment, and low tolerance for change. As shown, most re-searches in this field identify different, multifaceted reasons for resistance which are all appropriate. Nevertheless, those reasons show that employees react differ-ently to change: from passive resistance to

active opposition or even acceptance (Kot-ter and Schlesinger 1979).

However, for a company it is beneficial to quickly adapt to environmental changes, explore new ideas or processes, and reduce fixed costs in order to be competitive. Some individuals also seek changes be-cause this is providing a variety in their work, fulfilling self development needs, and maintaining interest in and satisfaction with their jobs. Piderit (2000) discusses the positive and negative aspects of a resis-tance to change. Successful change man-agement in companies relies on generating employee support and enthusiasm for changes, rather than overcoming resis-tance. In addition, we need to see the rea-sons behind resistance, especially if they are unselfish, and not just the resistance as a threat. One of three examples in this arti-cle results from an interview with a middle manager in a large, diversified company, describing his response to the restructuring and centralisation of his company around a new enterprise-wide ERP system. In this case, the employee started off enthusiastic but became dissatisfied due to the lack of top management support, co-workers’ lack of interest and commitment, and what he perceived as the dangers of a “behemoth project” (Piderit 2000, p. 788).

Returning to the WZM Werkzeugmaschi-nen GmbH, they also recognised that

resis-tance evolved as the project advanced. Es-pecially some of the key users in the ad-ministration department were not willing to use the ERP system for their daily work. Reasons therefore are trivial:

• Some employees are 50 years and above and their experience with computers is very low.

• Some employees do not accept the change of their processes.

For WZM Werkzeugmaschinen GmbH it is an additional effort to change the attitude of the employees and to overcome the re-sistance.

As for WZM Werkzeugmaschinen GmbH, the system implementation and the process change, in general, affect the people within the organisation and can lead to project failure if not regarded as serious. Accord-ing to HawkAccord-ing et al. (2004) many compa-nies struggle during the implementation phase due to the underestimation of the complexity and the lack of experience for the change process.

To support Hawking et al. (2004), Nah et al. (2001) recognized that an ERP does not necessarily induce the expected changes. In other words, it is not because an organi-sation implements an IT system that social changes will necessarily occur. Technol-ogy itself does not induce the collective process which is necessary for a successful ERP implementation. Moreover, the

em-ployees are able to make a success, or a failure, or neutralise complex systems such as ERPs.

ERP-Implementation – identifying the critical success factors

As discussed before, significant technical challenges posed by ERP are an important part within a project. Al Mashari et al. (2003) views ERP as an enabler for reen-gineering and changing the processes, roles, and structures within a company. However, researchers agree that organisa-tional factors are most critical to successful ERP implementation (Al-Mashari et al. 2003, Shanks et al. 2000, Esteves-Souza and Pastor-Collado 2000). As mentioned before, WZM Werkzeugmaschinen GmbH also faces several organisational changes and internal problems related to this radical change. During the post-implementation phase, there was strong resistance in the finance department due to the changes in the workflow, further the financial director was not willing to become acquainted with the system.

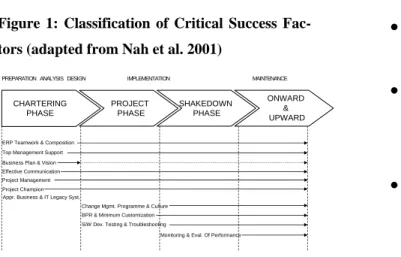

Nah et al. (2001) found that critical success factors are not yet researched in depth and there exist no standard critical success fac-tors. Therefore, it is necessary to identify the key critical success factors for an ERP project. Nah et al. (2001) proposed a framework (fig. 1) for critical success

fac-tors based on the ERP life cycle model of Markus and Tanis (2000). The framework clearly outlines the phases in which the factors are of importance for the project.

Figure 1: Classification of Critical Success Fac-tors (adapted from Nah et al. 2001)

CHARTERING PHASE PROJECT PHASE SHAKEDOWN PHASE ONWARD & UPWARD

ERP Teamwork & Composition Top Management Support Business Plan & Vision Effective Communication Project Management Project Champion Appr. Business & IT Legacy Syst.

Change Mgmt. Programme & Culture BPR & Minimum Customization S/W Dev. Testing & Troubleshooting

Monitoring & Eval. Of Performance

PREPARATION ANALYSIS DESIGN IMPLEMENTATION MAINTENANCE

But before discussing this framework and the applied critical success factors more in depth, one should understand the definition of success which research defines in two ways.

First, success of ERP projects can be de-fined as: meeting project deadlines, work-ing cost efficient, and sustainwork-ing harmony among the various employees involved in the ERP implementation (Nah et al. 2001). Although these are merely indicators of success rather than final outcomes, they are important because ERP systems have to be implemented before final outcomes can be recognised.

A second way to define success is to con-sider the generate value from ERP system implementations. Successful implementa-tions do not necessarily yield any long-term benefits, but certain factors have been

found to be associated with value. Those factors can be identified as key to generat-ing benefits from an ERP system which includes the following variables (Ross 1999; Willcocks and Sykes 2000):

• measures which clarify managerial goals for the ERP,

• development of process expertise and structures for managing across functions,

• responsibility for generating bene-fits.

Returning to figure 1, Nah et al. (2001) have found eleven critical factors which correspond to the results of the examined articles. However, Nah et al. (2001) have added up all factors identified and put them into a framework. But some of the exam-ined articles have not identified all named critical success factors. Therefore it is not appropriate to sum them all up. Instead one has to balance which factors are really cor-responding to the success of the project. Several researchers have found factors which are critical to the success of ERP implementation projects (Bingi et al. 1999; Holland et al. 1999; Sumner 1999; Umble et al. 2003). According to Nah et al. (2001) analysis, the following factors have been identified as most common:

• compelling vision and understand-ing of the strategic and operational goals,

• top management support (through leadership, participation, and com-mitment) for the ERP project team and the implementation process,

• effective full-time management by a project team including employees with IT- and business know-how,

• commitment to change throughout the organisation,

• effective communication of the project to all stakeholders.

For the most part, the studies of critical success factors hold few surprises. The factors are obvious and not distinguishable from the outcomes of implementation suc-cess that they allegedly predict. Further-more, factors such as top management support and commitment to the change are not substantially different from critical success factors of most IT projects and to organisational change of other kinds. It is not clear how these studies contribute to a specific understanding of critical success factors of ERP projects, unlike other types of projects. Moreover, the factors de-scribed in the literature are not framed by appropriate concepts or theories. In these cases, neglecting theory causes bias in ex-plaining why the factors identified are critical to success in general. The studies, as a group, also manifest deficiency in re-search design and analysis, thus limiting their value. However, it is important to

begin the research for critical success fac-tors of ERP projects somewhere, and the factors identified are certainly areas of concern. Nevertheless, further research needs to incorporate a stronger theory base and to utilise more rigorous research meth-ods.

Returning to WZM Werkzeugmaschinen GmbH, they realised that they were facing a high risk, not only because of the imple-mentation costs and the technical endeav-our, but also due to the prospect of major changes in business processes and organ-isational structure. This was the core rea-son why WZM Werkzeugmaschinen GmbH adjusted slowly to the inherent complexity of their ERP system. Schneider (1999) also reported that ERP projects of-ten experience high costs, and that about half of all ERP projects fail to achieve promised benefits. This result mainly oc-curs because managers significantly under-estimate the efforts involved in managing change. WZM Werkzeugmaschinen GmbH also experienced first evidence that the implementation project is about to fail. Some participants within the project have missed their project deadlines due to resis-tance among the employees who have to adapt the new system. As a consequence, this delay causes further costs and post-pones the schedule.

When looking at the theory of change management, Van de Ven and Poole (1995) offer four alternative types of methods that influence organisational changes: dialectical, teleological, evolu-tionary, and life-cycle. On the basis of Van de Ven and Poole’s (1995) theoretical analysis of organisational change, ERP-enabled change can be seen as a dialectic approach that focuses on the balance be-tween forces promoting and forces oppos-ing change. Robey et al. (2002) have adapted this approach to improve the im-plementation process of ERP systems.

The dialectics approach is defined as an exchange of propositions (theses) and counter-propositions (antitheses) resulting in a disagreement which is tried to be re-solved through rational discussion. These so called dialectics can be used to explain the diversity of organisational conse-quences of IT, and also to explain the di-versity of outcomes observed in ERP re-search (Robey and Boudreau 1999). There-fore, one can assume that any particular implementation project would be expected to manifest forces promoting change and forces opposing change. In this way, Robey et al. (2002) explained a variety of potential outcomes, using the dialectic ap-proach. They see the core dialectic in knowledge, embedded in business proc-esses and organisational habits, as a key

variable for raising conflicts. Old processes are memorised and employees are accus-tomed to them. Therefore it is suggested to change structures and processes of entire divisions. However, changing the proc-esses does not ease the adaptation for the employees; instead it increases the resis-tance to change. Robey et al. (2002) argue that organisational learning is the key to overcome resistance to change using train-ing and steertrain-ing mechanisms. Of course, training and guidance are essential to change the employees’ perception of the new situation, but this process does not ensure that employees accept the change.

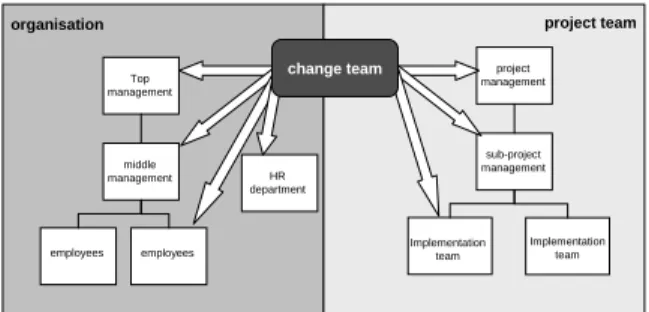

Focusing on change management in such a project, one has to place emphasis on sev-eral change management activities. Scherer (2001) states that focusing on certain is-sues is necessary and can be identified through generating change portfolios (Fig. 1). Those portfolios characterise the inter-section between the technological and or-ganisational change, and further between the cultural and the organisational change. The cultural change describes the percep-tion and adaptapercep-tion of the individuals. Therefore it is again necessary to consider the personal resistance to change as an important factor.

Figure 2: Change Portfolios ada pt io n o f t h e E R P sy stem change of organisation technological change management or g ani s a ti onal c hang e m a n a g e m e n t re s ist an c e to c h a nge change of organisation cultural change management or ga ni s a ti o n al c h a n g e m an a gem en t

As we have seen in the previous para-graphs, change management plays an im-portant role during ERP implementation projects. We have also identified some critical success factors and revealed the appearance of resistance to change. In the following paragraphs we further discuss the change an organisation, and especially its employees, face and how the change within ERP projects can be managed.

Change management and the effects on the employees

During the ERP implementation at WZM Werkzeugmaschinen GmbH there was a profound impact on the processes, the workplace, and on the employees. For ex-ample, some employees could not accept the new screen layout of the ERP software and the new navigation within the ERP software. It was difficult for those employ-ees to abandon their old habits and adapt themselves to the new system. Moreover, the employees regarded this project as an IT project. According to Nah et al. (2001)

this perception is wrong because it gener-ates aversion and prejudices.

However, it is necessary to introduce a situational and organised change manage-ment (Scherer 2001). WZM Werkzeug-maschinen GmbH, in contrast, did not rec-ognise the importance of this change and first started without a project leader who leads this project full-time. Instead they divided the tasks of the project on some employees in addition to their operational work. Furthermore they applied two con-sultants to integrate the ERP system into the workflow of the company. As WZM Werkzeugmaschinen GmbH was not able to assign a full-time project leader, it was necessary that the consultants led the pro-ject. This generated an uncomfortable feel-ing among the employees because they were not convinced if the consultants were competent. Hirt and Swanson (1999) re-ported on a similar project at Siemens Power Corporation. There consultants also caused unease among the employees be-cause they missed to communicate their progresses to the employees.

The cases described by Hirt and Swanson (1999), and Ross (1999) show that false communication and the engagement of consultants causes mistrust among the em-ployees and therefore supports and multi-plies resistance. Moreover, it is necessary that companies position the project from the start as an enterprise project and

com-municate the steps of the project within the company. Furthermore, Scherer (2001) suggests introducing two teams (Fig. 2):

• A project team which consists of a project manager and interdiscipli-nary team members composed of key users, IT specialists, and con-sultants if necessary.

• A change team which is composed of employees from all departments concerned, middle and top man-agement, project members, and ex-ternal training consultants.

Figure 3: involvement of a change team in an ERP project project team organisation Top management middle management employees employees HR department project management sub-project management Implementation team Implementation team change team

The setting up of a project team is surely one factor for managing the change and overcoming the resistance among the em-ployees. But it is a composition of several factors ensuring that resistance will be em-banked and that the change will be ac-cepted all across the company. Therefore the following table outlines all identified critical success factors from the previous paragraph and describes a best-practice approach. Table 1 is based on the findings of Al-Mashari and Zairi (2000b) and Kot-ter and Schlesinger (1979).

As pointed out in table 1, change manage-ment mainly influences the workplace of each individual within the company. This often requires a collective way of manag-ing the change.

Table 1: Critical success factors and best-pracitce change management

Dimension Description

Involving and inform-ing employees early enough

A lack of information and communication leads to mistrust among employ-ees. Therefore it is necessary to inform and involve employemploy-ees. On the other hand, it is critical and time-consuming to include representatives from each department in ERP implementation efforts as early as possible.

Commitment of top management

When those people who manage the project do not expect any improvements and are not led properly, they cannot convince others about the change. Therefore, top management should commit to ensure that the company will exceed customers' expectations, achieves growth targets, and maintains in-dustry leadership in order to unify the several entities within the company. Leadership and project

management

It is important to place the ERP venture as a project to spread feelings of confidence, competence, and persistence among the employees. Stevens (1997) reports on Kodak’s ERP project. There, major decisions were made by a strategy group consisting of participants from top management, manu-facturing, marketing, HR, consumer imaging unit, and shared services.

Em-ployees felt that the project was pushed ahead because the commitment of the group members was obvious, and well positioned.

Educating and sup-porting all users

Employees’ resistance also arises because they cannot handle with the navi-gation of the new ERP system. Therefore it is necessary to provide them with training measures e.g. online-training centres, etc.

Further resistance could arise if tasks within the system do not work at first go. Therefore it is useful to establish a support centre and a user help-desk. Communication of

current project status

As part of a project information policy, the establishment of extensive inter-nal communications channels, including focus groups, newsletters, e-mail, and web-based archives, is useful to get employees informed about the status, new developments, and answer questions about the ERP system.

Marks et al. (2001) note that teamwork is a basic way of solving tasks within a com-pany. Therefore Marks et al. (2001) found that people who are working together can solve problems faster and beyond the ca-pabilities of employees who are working alone. Furthermore these outcomes are not only the result of the team members’ skills, and the available resources. Moreover, this is a result of the processes team members use to interact to manage the work.

In the case of the ERP implementation at WZM Werkzeugmaschinen GmbH, the tasks were setup; the ERP system was im-plemented, customised, and extensively tested to validate the system prior to end user training and “Go Live”. The tasks were associated with the ERP modules, for example for Finance: Accounts Payable, Accounts Receivable, General Ledger, Fixed Assets, etc. Throughout the ERP implementation project there was a need for frequent dialogue and meetings to iden-tify the relations between the ‘Finance’

module and the ‘Logistics’ module or the ‘Manufacturing’ module as part of the cus-tomizing.

A major difficulty was the switch from a functional to a process orientation, due to the fact that modules cut across traditional departmental lines. During the adaptation of the system, the company realised that implementing an ERP was an interdiscipli-nary task and could not only be driven by the technical implementation (which was driven by the consultants). Therefore, WZM Werkzeugmaschinen GmbH had to assign a project team rapidly in order to not lead the project into failure and to broaden the scope of the change.

In general and in the case of WZM Werkzeugmaschinen GmbH, it is obvious that individual or group dynamic effects cannot be controlled due to the fact that they do not adhere any predefined plan-ning. Furthermore, a company should not start from the ERP technical solution, but from problems to solve. WZM

Werkzeug-maschinen GmbH neglected to identify actual needs before implementing and adapting a technical solution. Furthermore, it is essential to remain attentive to people and social behaviour in order to be able to analyze problems and evaluate needs. Moreover, the company should provide support and educate its employees: both individual education (learning what the ERP modules are doing and how to use them) and collective education (learning how to integrate the ERP in each depart-ment or service operational practices). As previously mentioned, the finance depart-ment of WZM Werkzeugmaschinen GmbH heavily opposed the change, because they lack the skills to use the ERP system. Too late, WZM Werkzeugmaschinen GmbH realised that coping with all the new ac-counting features of the ERP Finance module requires building a new knowledge base among all the employees first, then in the department as a whole. In fact, any success depends on the collective educa-tion of the organisaeduca-tion (Marks et al. 2001).

The people focus is often missing in ERP projects – as the case of WZM has shown – and may explain in parts, why ERP pro-jects fail. Furthermore, Miller (2001) em-phasises the importance of education and training: “People are always key to any process improvement, so methods to help staff ramp up on the learning curve of a

technology or process are extremely

im-portant.” (p. 19). In other words, it is

nec-essary to help the older key user (50 years and above) with over 20 years business experience to become an internal consult-ant in the ERP system.

As shown above, another reason for con-tinued project failure is the notion of man-agement. In the case of WZM Werkzeug-maschinen GmbH the management only concentrated on the technical implementa-tion.

Moreover, it is important to see the change as a whole. In an article about the near future, Drucker (2001) describes how change can be managed within an organi-sation: “The most effective way to manage change successfully is to create it. But ex-perience has shown that grafting innova-tion on to a tradiinnova-tional enterprise does not work. The enterprise has to become a change agent. […] Instead of seeing change as a threat, its people will come to

consider it as an opportunity.” (p. 21).

Conclusion

This paper highlights two facets of change management in ERP implementation pro-jects: technical implementation and con-figuration of the system, and the organisa-tional familiarisation with the software and its related changes. The technical imple-mentation initialises the radical change and

demands several success factors to be ful-filled (e.g. technical requirements, adapta-tion of processes, etc.). As the practical examples have shown, those tasks are managed by a core team consisting of em-ployees and consultants. The organisa-tional and personal change demands inten-sive information, communication, and edu-cation for the employees and appears to be more effective with incremental implemen-tation plans. Moreover, companies differ in their approach to implementing ERP sys-tem: some companies choose a piecemeal approach and others a concerted approach (Robey et al. 2002).

The work also identified several situations for the occurrence of resistance and meas-ures how to overcome resistance. How-ever, the most problematic issue related to resistance is that there is no resistance per se. Egan and Fjermestad (2005) found that resistance does not arise because of habits gained, or because of any “social inertia” (p. 220). However, resistance to change does occur and has got three origins:

• People resist, because they lack the skills to use and gain benefits from the new system.

• People resist, because they do not understand the changes initiated by the application of the new ERP sys-tems and the changes in business processes and workflow.

• Finally, resistance, especially in middle and upper management, emerges because the translation of ERP-related changes into new business models redefines the or-ganisational structures and the allo-cation of competencies and respon-sibilities (Wargin and Dobiey 2001).

Therefore, employees do not resist just for the sake of resisting, but build their needs depending on their goals and evolution of beliefs and habits. The superior reason is fear: employees fear that they cannot keep themselves up-to-date with technology and therefore fear for their jobs. As technology evolves at such a pace that it generates so called ‘techno-stress’ among employees at all levels of an organisation (Kakabadse et al. 2001). In fact, Korac-Kakabadse et al. (2001) have found that employees say they are ‘techno-stressed’ because they have to learn, know and use new technologies or systems. Moreover, they consider that they have nearly no con-trol over the choice of technologies that are deployed within the organisation and they lack of training on them.

As a measure to overcome resistance the paper identified important critical success factors which can be categorized by its occurrence in ERP projects. In addition, Somers and Nelson (2001) have identified

the importance of critical success factors by phases, which supports that there are mainly five important factors throughout the phases: top management support, pro-ject management, communication, educa-tion and training, and involvement of em-ployees in all project steps. The manage-ment of those factors is essential for the success of the project and to overcome the resistance within the company.

However, an ERP implementation impacts the whole company, especially the work-place of each individual and the members who are part of the project team. In the context of WZM Werkzeugmaschinen GmbH, the paper has shown that change management means an upheaval of exist-ing work methods – the breakexist-ing down of barriers between countries, sites, functional divisions and hierarchies. Self interest, defending one’s position within the organi-sation, and internal politics can of course continue to dominate the project and lead to failure. A successful project manage-ment and the consideration of the critical success factors are enablers to push these indications of resistance into greater good, project success and win-win for the organi-sation and employees alike. Therefore one should emphasis that learning plays an important role in integrating and familiar-izing employees with the ERP system.

References

Aladwani, A. M. (2001). Change manage-ment strategies for successful ERP im-plementation. Business Process

Man-agement Journal, 7 (3), pp. 266-275.

Al-Mashari, M. (2003). A Process Change-Oriented Model for ERP Application.

International Journal of

Human-Computer Interaction, 16 (1), pp.

39-55.

Al-Mashari, M., Al-Mudimigh, A., and Zairi, M. (2003). Enterprise resource planning: A taxonomy of critical fac-tors. European Journal of Operational

Research, 146 (2), pp. 352-364.

Al-Mashari, M., and Zairi, M. (2000a). Information and Business Process Equality: The Case of SAP R/3 Imple-mentation. The Electronic Journal on Information Systems in Developing

Countries (EJISDC), 2, pp. 1-15.

Al-Mashari, M., and Zairi, M. (2000b). The effective application of SAP R/3: a proposed model of best practice.

Logis-tics Information Management, 13 (3),

pp. 156-166.

Bingi, P., Sharma, M. K. and Godla, J. K. (1999). Critical Issues Affecting an

ERP Implementation. Information

Sys-tems Management, 16 (3), pp. 7-14.

Caruth, D., Middlebrook, B., and Rachel, F. (1985). Overcoming Resistance to Change. SAM Advanced Management

Journal, 50 (3), pp. 23-27.

Davenport, T. H. (1998). Putting the En-terprise into the EnEn-terprise System.

Harvard Business Review, 76 (4), pp.

121-131.

Drucker, P. (2001). The next society: A survey of the future. The Economist, 361 (8246), pp. 3-22.

Egan, R. W., and Fjermestad, J. (2005). Change and Resistance Help for Practi-tioner of Change. In Proceedings of the

38th Hawaii International Conference

on System Sciences, pp. 219-226.

Esteves-Souza, J. and Pastor-Collado, J. A. (2000). Towards the unification of critical success factors for ERP imple-mentations. In Proceedings of the 10th Annual Business Information

Technol-ogy Conference, Manchester, UK.

Hawking, P., Stein, A., and Foster, S. (2004). Revisiting ERP Systems: Bene-fit Realisation. In Proceedings of the

37th Hawaii International Conference

on System Sciences, pp. 227-234.

Hirt, S. G., and Swanson, E. B. (1999). Adopting SAP at Siemens Power Cor-poration. Journal of Information

Tech-nology, 14 (), pp. 243-251.

Holland, C., Light, B., and Gibson, N. (1999). A Critical Success Factors Model for Enterprise Resource Plan-ning Implementation. In Proceedings of the European Conference in

Infor-mation Systems, Copenhagen, pp.

273-285.

Korac-Kakabadse, N., Kouzmin, A., and Korac-Kakabadse, A. (2001). Emerg-ing impacts of on-line over-connectivity. In Proceedings of The 9th European Conference on Information

Systems, Bled, Slovenia, pp. 89-97.

Kotter, J. P., and Schlesinger, L. A. (1979). Choosing strategies for change.

Har-vard Business Review, 57 (2), pp.

106-114.

Leana, C. R., and Barry, B. (2000). Stabil-ity and Change as Simultaneous Ex-periences in Organizational Life.

Acad-emy of Management Review, 25 (4), pp.

753-759.

Marks, M. A., Mathieu, J. E., and Zaccaro, S. J. (2001). A temporally based

framework and taxonomy of team processes. Academy of Management

Review, 26 (3), pp. 356-376.

Markus, M. L., and Tanis, C. (2000). The enterprise system experience – from adoption to success. In Zmud, R. W. (Ed.), Framing the Domains of IT Re-search: Glimpsing the Future Through

the Past, Cincinnatti: Pinnaflex, pp.

173-207.

Martin, M. H. (1998). Smart managing.

Fortune, 137 (2), pp. 149-151.

Miller, A. (2001). Guest Editor’s Introduc-tion: Organizational Change. IEEE

Software, 18 (3), pp. 18-20.

Nah, F. F-H., Lau, J. L.-S. and Kuang, J. (2001). Critical factors for successful implementation of enterprise systems.

Business Process Management Jour-nal, 7 (3), pp. 285-296.

Piderit, S. K. (2000). Rethinking resistance and recognizing ambivalence: a multi-dimensional view of attitudes toward an organizational change. Academy of

Management Review, 25 (4), pp.

783-794.

Robey, D., and Boudreau, M.-C. (1999). Accounting for the Contradictory

Or-ganizational Consequences of Informa-tion Technology: Theoretical Direc-tions and Methodological ImplicaDirec-tions.

Information Systems Research, 10 (2),

pp. 167-185.

Robey, D., Ross, J. W., and Boudreau, M. (2002). Learning to Implement Enter-prise Systems: An Exploratory Study of the Dialectics of Change. Journal of

Management Information Systems, 19

(1), pp. 17–46.

Ross, J. (1999). Dow Corning Corporation: Business Processes and Information Technology. Journal of Information

Technology, 14 (3), pp. 253-266.

Scherer, E. (2001). Den Mehrwert ent-decken – Change Management & IT-driven Innovation [Discovering the added value – change management & IT-driven innovation]. Industrie

Man-agement, 17 (4), pp. 27-31.

Schneider, P. (1999). Wanted: ERPeople Skills. CIO Magazine, 12 (10), pp. 30-37.

Shanks, G., Parr, A., Hu, B., Corbitt, B., Thanasankit, T., and Seddon, P. (2000). Differences in critical success factors in ERP systems implementation in Australia and China: A cultural

analy-sis. In Proceedings of the 8th European Conference on Information Systems,

Vienna, Austria, pp. 537-544.

Somers, T. M., and Nelson, K. (2001). The Impact of Critical Success Factors across the Stages of Enterprise Re-source Planning Implementations. In

Proceedings of the 34th Hawaii

Inter-national Conference on System

Sci-ences, 2001, pp.

Stevens, T. (1997). Kodak focuses on ERP.

Industry Week, 246 (15), pp. 130-135.

Sumner, M. (1999). Critical Success Fac-tors in Enterprise Wide Information Management Systems Projects. In Pro-ceedings of the Fifth Americas

Confer-ence on Information Systems,

Milwau-kee, Wisconsin, pp. 232-234.

Umble, E. J., Haft, R. R., and Umble, M. M. (2003). Enterprise resource plan-ning: Implementation procedures and critical success factors. European

Journal of Operational Research, 146

(2), pp. 241-257.

Van de Ven, A. H., and Poole, M. S. (1995). Explaining Development and Change in Organizations. Academy of

Management Review, 20 (3), pp.

510-540.

Wargin, J., and Dobiey, D. (2001). E-business and change – Managing the change in the digital economy. Journal

of Change Management, 2 (1), pp.

72-82.

Willcocks, L. P., and Sykes, R. (2000). The Role of the CIO and IT Function in ERP. Communications of the ACM, 43 (3), pp. 32-38.