Known occupational exposure to health risks:

How the Dutch armed forces handled expertise regarding chromium-6 in the

face of social amplification of risk.

Master thesis

Name: Colin Crooks

Student Number: s1384856

First reader: Dr. M.L.A. Dückers Second reader: Dr. S.L. Kuipers Capstone Public Safety & Health Master Crisis & Security Management June 10, 2018, The Hague

Leiden University

2

Abstract

This thesis surrounds the 2014 crisis or scandal on the exposure of employees of the Dutch armed forces to chromium-6. The reason for this research is that media coverage claimed that there was knowledge of the risk and exposures to chromium-6 at the time of the exposures happening. One of the possible explanations is that a bad safety culture over time stopped organizational improvement from happening. Theory on safety culture is mostly used commercially in industrial settings and healthcare, which provides a chance to see if safety culture theory can also be applied in a governmental context. The research question is: “Why

was the scandal of occupational exposure of maintenance personnel with the Dutch armed forces to chromium-6 not addressed while there was expertise on the risk of exposure and knowledge of exposures?”. This question is answered by making use of theory from the field

of safety culture, social amplification of risk and agenda setting. The expectations are that between 2000 and June 2014, a continuously bad safety culture leads to the amplification of risk through media attention. This amplification of risk between June 2014 and June 8, 2018 produces pressure for legislative and organizational change, which drives a change in safety culture. The methods consist of qualitative content analysis of internal documents of the Dutch armed forces, media coverage, debate transcripts and documents from advisory bodies. The results show that in the first time period, the Dutch armed forces try to improve safety after political attention to exposures in 1998 and 2001. Safety culture improves from a pathological culture to a more calculative culture, but these improvements are not made or made at a slow pace. The effects of improvements diminish, resulting in alternating between a calculative and reactive safety culture in which the armed forces over the years must react to warnings from the labour inspection up until 2012. The results find that the second period is characterized by amplification of risk in the increase of the amount of media coverage and repetition of articles. This results in pressure for change produced by the Health Council, politicians, media coverage and research by the RIVM. The available data cannot say if safety culture has improved yet,

but there are new plans for improvement. The answer to the research question is that employees were knowingly exposed to chromium-6, while upper management had knowledge of the

3

Foreword

Before you lies the master thesis ‘Known occupational exposure to health risks’. The research on the Dutch armed forces was conducted with the help of qualitative analysis of documents from the Dutch armed forces and media articles. This thesis was written as a part of the master Crisis & Security Management at Leiden University.

This thesis was supervised by Dr. Michel Dückers from the Netherlands institute for health services research (NIVEL) as a part of the Public Safety and Health capstone, set up by Dr. Sanneke Kuipers. I would like to thank Dr. Michel Dückers for his guidance and feedback

during the writing process of this thesis, especially his comments after the first draft which helped me to further refine the final thesis. I would like to thank Dr. Sanneke Kuipers for setting up the capstone, which allowed for the exchange of ideas with fellow students and the easy availability of expertise.

I would also like to thank Dr. Jeroen Devilee from the National Institute for Public Health and the Environment (RIVM) and his colleagues for their suggestions and ideas on the theoretical framework for this thesis. Being able to discuss the thesis with them allowed their inspiration to let me take this thesis to the next level.

Lastly, I would like to thank my parents and close friends, who gave me the motivation to conduct my research when morale was low. Their encouragement and discussions were essential to me writing this thesis and completing it.

Colin Crooks

4

Table of contents

Abstract ... 2

Foreword ... 3

Chapter 1: Introduction ... 5

1.1 Introduction ... 5

1.2 Research question ... 6

1.3 Relevance ... 7

1.4 Readers guide ... 8

Chapter 2: Theoretical framework ... 9

2.1 Slow-burning crises and scandals ... 9

2.2 Safety culture ... 10

2.4 The social amplification of risk as agenda setting ... 16

2.5 Theoretical model and hypotheses ... 19

Chapter 3: Research design & methods ... 22

3.1 Research design ... 22

3.2 Research methods ... 23

Chapter 4: Case description ... 32

4.1 Policy and developments on chromium-6 paint between 2000 and June 2014 ... 32

4.2 Background on events and developments after June 2014 until June 2018 ... 34

Chapter 5: Analysis ... 39

5.1 Safety culture before the crisis ... 39

5.2 Social amplification of risk, pressures for change and safety culture during and in the aftermath of the crisis ... 46

5.2.1 Social amplification of risk ... 46

5.2.2 Legislative pressure and pressure for organizational change... 51

5.2.3 Safety culture ... 52

5.3 Theoretical implications ... 55

Chapter 6: Conclusion ... 57

6.1 Answer to research question ... 57

6.2 Discussion ... 58

6.3 Limitations and suggestions for further research... 59

5

Chapter 1: Introduction

1.1 Introduction

For decades, the Dutch railways and the Dutch armed forces have made use of paint containing hexavalent chromium (chromium-6), a metal which is meant to prevent corrosion on for example tanks, planes or trains. The metal itself is not hazardous when it is in solid state in applied paint but poses a serious health risk when the paint is sanded down or sprayed on to objects without the proper protection for one’s skin and respiratory system (RIVM, 2017). In 2014, a report came out that since the 1980’s technical maintenance employees working on maintenance of tanks and later airplanes in NATO workplaces for the Dutch armed forces had

been exposed to this metal, even though efforts were made to ban the substance from the workplace when it was discovered that exposure to the metal could cause cancer and other diseases (Drost.nl, 2018). When a large number of employees who had worked in these workplaces reported health problems and that they thought that the cause was to blame to exposure to chromium-6 from paint, media was quick to pick up the reports and turn it into a scandal.

The going public of approximately 2100 suspected victims led to a lot of media attention and political pressure for the Minister of Defence, Jeanine Hennis-Plasschaert (Bhikhie, 2015). The political problem was that Hennis was responsible for this crisis happening while being the Minister of Defence because the Dutch armed forces were under her leadership. Hennis had to deal with harsh debates and take responsibility by offering solutions to the crisis. In short, Hennis suspended the use of paint containing chromium-6 on several air force bases because they were not equipped for the safe use of this paint. Additionally, Hennis commissioned a large investigation by the Dutch National Institute for Public Health and the Environment (RIVM), under the guidance and support of a commission which consists of representatives from all involved interests (Informatiepuntchroom6.nl, 2015; Volkskrant.nl, 2014). This commission consists of representatives from law firms representing victims, labour unions, health researchers and representatives on behalf of the employer. A large study would be conducted

6 Interesting is that the Dutch armed forces were aware of the found levels of chromium-6 in their workplaces, and that these exceeded the legal exposure limit (Drost.nl, 2018). The armed forces either did not address this problem or failed to address it in a satisfying manner. Legislation exists which limits the allowed concentration of chromium-6 in the workplace and makes the use of protective gear mandatory, but for some reason signals of bad work conditions and violation of the allowed limits were not addressed.

Furthermore, the recently completed literature study of the RIVM on the effects of chromium-6 on human health shows that there is a lot of scientific knowledge and consensus on the effects of chromium-6 (RIVM, 2017). Striking is that we know for some time that chromium-6 has bad health effects and that there is broad consensus within the scientific community on the effects. However, regardless of this knowledge and new supporting knowledge becoming available over time, there was no real attention for enforcing legal exposure limits and the mandatory use of protective clothing. It is thus the legal exposure limit that the Dutch armed forces did not enforce, but they were also possibly aware of the negative

health effects or risks and failed to protect employees.

1.2 Research question

The research question for this thesis is:

“Why was the scandal of occupational exposure of maintenance personnel with the

Dutch armed forces to chromium-6 not addressed while there was expertise on the risk of exposure and knowledge of exposures?”

This question comes from the argument that there is overwhelming expert knowledge on the health effects of chromium-6, yet nobody acted upon new information to pursue stricter enforcement of the existing legal exposure limit at that time. Expertise is normally used by policy makers to give content to the policy or to fill in details such as new limits or requirements, but it begs the question if this expert knowledge did not reach the policy makers or was simply ignored because of the safety culture that the Dutch armed forces has.

7 political agenda setting which asked for solutions to the issue at hand. Drawing a comparison between the two time periods may provide insight into how there was a difference in information usage and the overall safety culture. The period following the date of the victims going public to the media (June 2014 up to this day) possibly shows the sudden usage of expert knowledge or expert advice by the Dutch armed forces, whereas they possibly ignored it before the scandal (between 2000 and June 2014) and the Dutch armed forces took the risk of possible exposure to chromium-6 for granted. This thesis seeks to examine if and why there was such a difference in knowledge utilization through safety culture between before and after the scandal came to light.

1.3 Relevance

On a societal level, research into this topic gives not only insight into how knowledge is utilized within governmental organizations such as the Dutch armed forces, but also contributes to understanding how expert knowledge potentially contributes to further crisis prevention. For example, as will be further explained in the theory, Pidgeon (1991, p. 131) explains how the utilization of knowledge and overall information interactions can be improved by improving

organizational culture, which prevents organizational failure. A better safety culture will thus come with a better utilization of knowledge on risks because a better safety culture will make sure that there is a continuous improvement of safety, which requires knowledge on which risks to look out for. Crises are then potentially prevented through saving human lives by spotting potential hazards that have not been accounted for thus far. By looking at why expert knowledge regarding these dangers was or was not utilized, we might be able to make recommendations on how for example a change in safety culture can help in preventing future crises and following public outrage. In the long term this means that better signalling and monitoring will contribute to less victims of long term crises. Crises that may fly under the radar of political figures and policy makers may be signalled at a much earlier stage and addressed internally by the organization.

8 that expert knowledge on the risk was available, but somehow it did not trigger more strict enforcement or improvement, even though there was information of exposures happening. The habits and behaviours that surround being informed about risks and dangers can be found in the field of safety cultures. Safety culture theory and the commercial programs constructed from its theory are mostly aimed at private commercial organizations. For example, Patrick Hudson together with his team of researchers worked on the development of the ‘Hearts and Minds’ program for Shell to be able to improve safety culture with oil and gas companies (Hudson, Parker, & van der Graaf, 2002). Struben & Wagner (2006) took Hudson’s framework to adapt it into being able to be used in hospitals regarding patient safety, which was developed into the commercial IZEP method. More recent papers look to expand the application of an underlying framework by Westrum on patient safety, as Ashcroft, Morecroft, Parker & Noyce (2005) apply the framework to safety within pharmacies. Research into safety cultures has thus far focussed on industrial manufacturing, healthcare organizations and oil and gas companies which do not allow for a big margin of error. It is the question if the model by Hudson is also applicable to governmental organizations, which are not engaged in pure engineering but do handle hazards

and risks like industrial companies. This would contribute to the gap in research regarding the applicability of safety culture frameworks on different organizations. Furthermore, it would also contribute to the usage of different methods, as research on safety culture relies mostly on surveys and interviews. This thesis looks to construct safety culture from document analysis. Further research will also contribute to further preventing slow burning crises happening in the future, or to at least contribute to being able to signal that something is going on which needs to be addressed to prevent it from becoming a crisis with long-term effects.

1.4 Readers guide

9

Chapter 2: Theoretical framework

2.1 Slow-burning crises and scandals

To go into the usage of knowledge in policy making in its function of preventing and solving crises, the topic of what crises are, how they can spread over time, and how the media scandalizes crises must be explained. Following the more traditional definition by Rosenthal, Charles & ‘t Hart (1989) I use the definition of crisis as: “a serious threat to the basic structures or the fundamental values and norms of a system, which under time pressure and highly uncertain circumstances necessitates making critical decisions” (as quoted in Rosenthal, Boin

& Comfort, 2001, pp. 6-7). It consists of three properties: threat, uncertainty and urgency.

Threat consists of potential physical harm, destruction or other types of harm. Threat does not necessarily have to lead to destruction, as it can also lead to social destabilization of neighbourhoods (Rosenthal, Boin & Comfort, 2001, p. 7). The high degree of uncertainty relates to the ability to understand what is going on outside of routine situations. Crisis disturb regular routines, which confuses policy makers and politicians as rules of thumb and procedures do not work anymore. Lastly, urgency or a sense of urgency means that crises are crucial moments for decision making (Rosenthal et al., 2001, pp. 7-8). Decisions must be made in a short time frame and under pressure under threat of for example more human deaths.

Crises may differ in the way they unfold. Most crises happen at an instant, such as explosions or natural disasters. However, there are also crises that unfold over the course of years. An example of this is an infection in the hospital which takes hundreds of lives of the course of years, which have creeping or slow burning characteristics (Connolly, 2015, p. 53; t’ Hart & Boin, 2001, p. 33; Rosenthal et al., 2001, p. 8). The problem is that these crises are not seen as crises at that time because people do not know what the problem is. Threats to public health from pollution or the usage of asbestos in construction are two of the countless examples that ‘t Hart and Boin (2001, p. 33) name. Only when the problem is discovered and defined,

they become crises, and as it is such a big problem, it also takes years to fully resolve the crisis. As media get tired and are focussing on new crises, the position of the crisis on the agenda has

ups and downs, dependent on new developments (t’ Hart & Boin, 2001, p. 34).

10 Media are likely to scandalize damages that were discovered as a consequence of political decision making because they are framed as a breach of trust of the public in politicians. The public has certain expectation of those who represent them in the Dutch Lower House, and this breach of trust provokes a strong emotional reaction. While Boswell finds that the media like to dramatize events and not focus on using expert knowledge, the media does make use of expert knowledge to expose the damage that was done, or to take a deeper look into the scientific basis that the government made its decisions on (Boswell, 2009, p. 172).

2.2 Safety culture

Something which may play a role in differing between both periods is the safety culture within the Dutch armed forces. Safety culture was a concept which was coined and gained traction after the Chernobyl disaster. Failures of sub-systems within organizations is often said to be the cause of a bigger system failing. This was the case with Chernobyl, where inquiries found that a bad safety culture was one of the causes of a nuclear explosion that cost 30 people their lives and many more in Europe in the form of increased risk of cancer (Wiegmann, Zhang, von Thaden & Gibbons, 2004, p. 119). Safety culture is mostly looked at from the perspective of

high risk organizations, such as oil, energy, aviation and space companies, and more recently health care.

While there are, as with all concepts that are well written about, countless of different conceptualizations of the concept of safety culture, I choose to use one of the definition of Wiegmann et al., who combine several other definitions:

“Safety culture is defined as the set of beliefs, norms, attitudes, roles, and social

and technical practices that are concerned with minimizing the exposure of employees, managers, customers, and members of the public to conditions considered dangerous or injurious.” (Wiegmann et al., 2004, p. 122).

11 Pidgeon (1991, p. 131) additionally argues that Turner’s model focusses on the information difficulties on determining safety problems and the failure of individuals to find a solution to the safety problems, which are often ill-defined. In this way, organizational culture, the behaviour, norms, values and other institutions could contribute to preventing future risks, disaster and crises by facilitating better information interactions, or the utilization of knowledge.

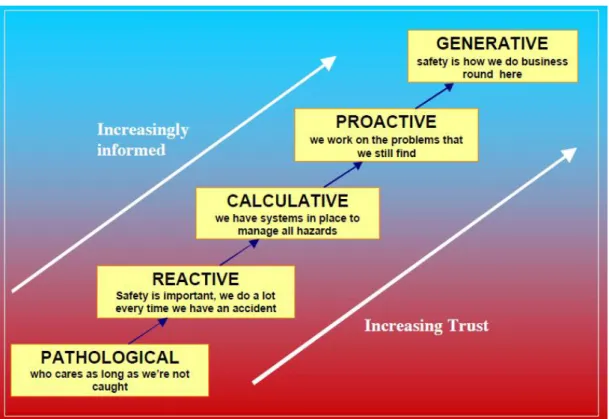

Wiegmann et al. (2004, p. 128) find that there is no one size fits all toolbox to assess the safety culture of an organization. While there is a wide range of models used by organizations in different sectors to assess the safety culture of an organization I will go through some relevant models to guarantee that the used models have enough theoretical support from other scholars. A big name in this field is Patrick Hudson, who devised a way to classify the safety culture of an organization. He divides cultures in four components: Corporate values, beliefs, problem solving methods and working practices (Hudson, 2001, p. 14). By taking the model of Westrum and adding two more types of cultures to it (reactive and proactive), the evolutionary ladder of safety cultures was made. This ladder goes from pathological to generative, with

reactive, bureaucratic or calculative and proactive in between (see figure 1).

12 Hudson, Parker & van der Graaf (2002, p. 3) explain pathological culture as one which is driven by a desire to not get caught and to blame workers when something goes wrong. The organization is not interested in looking out for safety. With reactive cultures, only an incident can trigger safety improvement. Incidents produce pressure from regulators, which pressures change. However, there is still a belief that employees are at fault for incidents. With a calculative or bureaucratic culture, safety is looked at from a managerial view by collecting a lot of data. Safety is calculated and incorporated in cost-benefit analyses. The organization forces itself under pressure of regulation to make procedures to guard safety, also protecting the organizations reputation. The proactive culture is characterized by a feeling within the organization that there are still uncertainties or chances that something might happen and that employees are also involved in safety management. The generative culture sees participation regarding safety improvement on every level, but there is some permanent unease because a crisis or safety incident may happen (Hudson et al., 2002, p. 3).

Hudson et al. (2002, p. 5) explain that safety culture can be assessed by looking at eighteen dimensions, which can be categorized regarding leadership & commitment, policy and

strategic objectives, organization, hazard management, planning and procedures, implementation & monitoring and audit and management review. By using statements or typical characteristics for every rung in the ladder of safety cultures for every dimension, one can determine in what rung of the ladder the organization can be found. I made the choice not to make use of all eighteen dimensions for this thesis as it does not fit the short timespan that this thesis is constructed in and the assessment method normally is used by large organizations in a bigger timespan. However, I selected some dimensions from almost all categories, which provides indication of the safety culture level in organizational terms. While Hudson et al. (2002, p. 6) give typical personal statements for every type of safety culture from the perspectives of management, supervisors and workforce, these are not given for every dimension and do not help in this case because this thesis relies on document analysis, and personal statements are not likely to be prevalent in documents. Therefore, looking at the broader organization and management will bring more benefit than the search for personal statements.

To give a broad overview of safety culture, Hudson et al. (2002, p. 2) explained their adaptation of Reason’s characteristics of a safety culture, adapted to four major dimensions.

13 Third, the culture is just, which means that there is trust between employees, and rewards for safety information instead of a blaming culture. Fourth, Reason names a culture to be flexible, in that the culture is adaptable together with the organization. Lastly, the culture promotes learning, which means that there is willingness and competence to learn lessons when something goes wrong and that there is willingness to reform. Hudson, Parker & van der Graaf also add worriedness to the list of cultural characteristics, as culture should make people uneasy because incidents can happen at any time, even if the organization has a good safety history.

Various authors, which include Hudson, developed the existing theory on the typology of safety cultures into the well-known ‘Hearts and Minds’ method by the Energy Institute, or made known by Shell. Part of this method is the ‘know your culture’ brochure, which makes use of Parker, Lawrie & Hudson’s (2006) description of the five different safety cultures regarding eighteen different dimensions of an organization, from the perspective of management and workforce. People normally are asked to score their experience of the organization’s safety culture based on the descriptions of the different dimensions (Energy Institute, 2006). The scores, for example when more characteristics from a reactive culture than

a generative culture are found, show that the organization is perceived to have a lower level safety culture, which has less trust and is less informed.

14

Table 1. Chosen dimensions for specific management system elements divided over

management and supervisors, from the safety culture framework by Hudson, Parker & Van der

Graaf (2002)

Management system element (Hudson, Parker & Van der

Graaf, 2002, p. 4)

Dimension (Hudson, Parker & Van der Graaf, 2002, p. 4)

Management or supervisor (Energy Institute, 2006)

Policy & Strategic objective Causes of accidents in eyes of management

Management

Organization & responsibilities

Workers interest in competency / training

Supervision

Hazards & Effects management

Worksite safety management techniques

Supervision

Implementing & Monitoring Incidents/accidents reporting analysis

Management

Implementing & Monitoring Who checks safety on daily basis?

Supervision

Audit Audits and reviews Management

Leadership & Commitment Management interest in communicating HSE (safety) issues with workforce

Management

The choice was made not to use the other management system elements: planning & procedures and management review. For the last one, there is only one dimension in this category, which revolves around benchmarking, trends and statistics. I made choice not to include this in the measured dimensions because it is hard to measure or to find in documents, and a focus on statistics is part of the more calculative safety culture, as this can be found within other descriptions. For the planning and procedures, the argument is that procedures and planning are also to some extent part of monitoring and the extent to which reports are made

and researched.

15 looking at who checks safety. The same goes for the dimension of hazard and unsafe acts reports, as incidents and unsafe acts have major overlap and the reporting of hazards can also be part of worksite job safety techniques, such as keeping track of what hazardous materials are being used. However, because of this overlap, these aspects of safety culture are also be addressed in the analysis to some extent. The dimensions named in the table above try to cover most of the management system elements, while also having a good division between management and supervision and incorporating possible overlap from other dimensions.

For the chosen dimensions of safety cultures, for each of the five types of safety culture, there is a description of what signs to look for regarding the dimension for that specific type of culture (Parker et al., 2006, pp. 557-559). For looking at causes of accidents in the eyes of the management, this means that a pathological safety culture has a lot of blame for individuals and acceptance of accidents as part of the job, whereas the generative safety culture has management accepting its own possible responsibility and looking at the overall system and interactions to address the cause of the accident. For workers interest in competency training, this goes from seeing training as necessary evil and compulsory by law and acceptance of harsh

16

2.4 The social amplification of risk as agenda setting

As the safety culture of an organization indicates how it does or does not process information, the bigger question around it is if the change in safety culture is rather a cause or an outcome of a crisis coming to light. For example, a continuously bad culture may lead to an increased public awareness and outrage in the form of risk amplification through media coverage, but this attention for the risk may also be the cause of a changing culture within an organization.

This increase in public attention, the so-called amplification of risk, is embodied by the Social Amplification of Risk Framework (SARF). Kasperson et al. (1988) are the architects of this framework, which explains how the attention to small risks leads to a strong public outrage and even societal or economic impacts. It seeks to show that hazards are connected with all kinds of psychological, social, institutional and cultural processes and that these can amplify or attenuate the public reaction to the risks themselves. Kasperson et al. (1988, p. 179) explain that this framework is needed as risks or incidents can lead to major secondary societal impact. Social amplification is named to be a corrective mechanism which improves the estimation of existing risks, and thus increases safety overall. However, the effect can also be the other way,

as it can also decrease attention for risks, such as which happened with the risks attached to smoking.

To give a definition of risk, I use of the definition of Rosa (2003), who defines risk as: “a situation or an event where something of human value (including humans themselves) is at stake and where the outcome is uncertain” (Rosa, 2003, p. 56). What is common in this

definition is the importance of danger to something of value, the possibility of an outcome occurring, and the uncertainty that surrounds activities. For example, people worry about the uncertainty that they might be harmed as the result of engaging in an activity that is harming humans, in this case being exposed to carcinogenic metal after working with paint.

17 pressure, changes in monitoring of risks and regulation, organizational change, changes in the feedback mechanism that increase or lower the risk itself and changes in training and qualifications (Kasperson et al., 1988, p. 182).

The amplification of risk works through receiving information, which consists of evaluating and constructing the knowledge, and transmitting information, adding new information to the message and thus amplifying the risk or signal going to other ‘stations’ (Kasperson et al., 1988, p. 181). The nature of the messages and what is in them also plays a role in how the messages are perceived by others. Kasperson et al. (1988, p. 184) argue that the information that goes through the amplification process may influence the degree of amplification through its volume, repeating stories and many other factors. Media compete for the attention of people, but large amounts of media attention shape the issue but also the agenda by repeating stories. As figures battle for media attention, it becomes much harder to reassure people. The volume of coverage is what creates the most attention for a subject.

Additional viewpoints on this role of media coverage come from Vasteman, IJzermans and Dirkzwager (2005), who see that SARF is closely linked with theory on agenda setting.

18 Leiss’ model of the role of media coverage in risk amplification makes use of

conceptualizations by Burns et al. (1993, p. 621), who recognize that the media has a significant strength in that their coverage impacts the public factors from risk signals that people perceive, and that their behaviour in turn leads to societal impact. In measuring this, the volume and repetition of coverage thus matters in reaching the public, but also messages about perception of bad managerial competence and future risks influence the societal impact through the forming of public opinion.

The interesting aspect about the social amplification of risk framework is that Kasperson et al. (1988) do not view the framework as a full theory on its own. They would recommend the usage of additional complementary theories to explain phenomena’s. A complementary theory is John Kingdon’s multiple streams theory, in trying to further illustrate how media attention drives public attention and leads to the secondary impacts in the SARF framework. Kingdon’s multiple streams method consists of problems, policy and politics. He recognizes the different kinds of groups engaged in the agenda setting process by naming the examples of academics, consultants, the media, and the public itself (Kingdon, 1984, p. 45). When it comes

to the media, Kingdon recognizes that the public attention to a problem is closely linked with media attention. Both citizens and legislators keep an eye on the media, and in this way media affect politics by influencing public opinion (Kingdon, 1984, p. 58). Politicians are thus driven by public opinion in that they must act to keep their support for upcoming elections.

Problems rise on the agenda because of focussing events in the form of crises, disasters, or personal experiences by policy makers (Kingdon, 1984, pp. 94-98). In terms of crises, instances lead to just signalling the problem and may take more crises to lead to a solution, so it is not entirely certain that one crisis leads to action from policy makers.

19 From the perspective of Kingdon, the social amplification of risk framework can be interpreted as problems being put on the agenda in the form of media attention following from a focussing event, which together with the political stream in the form of a worse public mood, allows for solutions such as the secondary impacts from the SARF framework to emerge. Political figures at the head of the government can as such be pressured to make new legislation or to enact organizational change, but this can also be done by governmental actors or experts putting pressure on the organization or politicians, as experts can argue for certain solutions. In the end politicians and a wide range of other actors such as inspections or experts can pressure ministers, state secretaries, and organizations for new legislation, and organizational change. These two factors are also described in the SARF framework as two of the secondary societal impacts. Kingdon (2014) understands these changes as being part of the solutions stream. One important clarification to make is that Kasperson et al. (1988, p. 182) do not link political pressure and other impacts in SARF, but Kingdon shows with his theory that there is a role that actors have in pressuring political figures, including politicians pressuring people within the administration for organizational change and a change in legislation. This is also supported by Gowda (2003), who uses Kingdon’s agenda setting theory to explain why different actors can

pressure legislators and politicians into enacting legislative change.

2.5 Theoretical model and hypotheses

20 Figure 2. Simplified theoretical model in overview

While there are countless of other confounding and interacting possible effects to be thought of, these cannot all be incorporated into the thesis. As said earlier in this thesis, this thesis aims to make a comparison between two time periods, one from 2000 until the crisis in June 2014, and the one during the crisis up until the present day. For the first period the question is if the

safety culture was already bad, or did drastically improve leading up to the crisis, to see if it could be a possible cause of what happens in the second period. In the second period, the question is if the possible amplification of risk and media attention for the crisis resulted in a higher level safety culture through the produced pressure. In short, the first period is characterized by a bad safety culture leading to risk amplification, and the second period is characterized by risk amplification possibly leading to a process of safety culture improvement or organizational change.

The first hypothesis coming from these expectations is that there is a lower level culture before the crisis, causing the amplification of risk. Considering that amplification of risk and change in safety culture is a ‘chicken or the egg’ question, I expect the first period to be

characterized by a bad safety culture regarding the Dutch armed forces, causing the amplification of risks. Information is not used, people do not care for safety in the period leading up to the crisis and are not prompted to improve the organization and its culture because they do not know that there is a problem. This brings me to hypothesis 1:

H1:A low level safety culture before the crisis leads to an amplification of risks in media

and public in the form of increased attention to safety risk with the Dutch armed forces. Safety culture Social amplification of

risk Pressure for

21 An important consideration to make is that when the culture has already been changing in the period leading up to the crisis, it is not certain that a bad safety culture has contributed to the crisis happening. However, it may or may not also have consequences for the second expectation or hypothesis, which is about the feedback loop. The second expectation is that the amplification of risk through the media and public and the overall attention leads to a change or improvement of safety culture with the Dutch armed forces through the production of pressure by amplification. According to SARF, some of the countless secondary societal impacts occur in the form of organizational change and changes in risk monitoring and regulation. While SARF also sees political pressure as one of these impacts, Kingdon explains that politicians are pressured by different actors, such as other politicians, experts, the media etc. to make changes in regulation and organizational changes. While there could be some overlap between the two periods regarding the end of period one and the beginning of period two, the first period is characterized by safety culture leading to the amplification, and the second to the amplification leading to pressures for regulation and organizational change which results in a change in safety culture. The second hypothesis is:

H2: The amplification of risk leads to secondary societal impact in the form of

regulatory pressure and pressure for organizational change to a higher-level safety culture

22

Chapter 3: Research design & methods

3.1 Research design

For this thesis, I choose to employ the multiple case comparison design. In this case, multiple cases do not consist of multiple crises, but two time periods surrounding the crisis in question. The crisis came to light when the media picked up the reports of victims who went public after they had feelings of not being heard by the government, in June of 2014, when Dagblad de Limburger (2014a) reported a story on former employees of a workshop being concerned about their health after measurements found chromium-6 in the workplace. It led to questions being asked in the Dutch Lower House on the 11th of July 2014 (Rijksoverheid.nl, 2014f). While this

crisis is one case in itself, I make the comparison between the two time periods because the media painted a picture of the government not addressing the exposure of employees before the crisis and questions what they did during the start of the crisis. It is interesting to see if there was a safety culture which allowed for the open usage of expert knowledge to address potential safety risks before the crisis, which would disprove the standpoint of the media. The second period, after June 2014, would then be characterized by knowledge usage by the organization.

The goal is not necessarily to find a causal link between social amplification of risk and safety culture, but rather to compare two time periods. It takes a deductive approach by taking existing theory on safety culture and the amplification of risk and applying it to the case of the Dutch armed forces to see if what they theory tells us happened in this case. Another point to consider is the internal and external validity of this design, while it is feasible, it is necessary to make sure that the method measures what it is meant to measure. The problem in this is that there are other factors which cannot be controlled for that might be of influence on what happened. It is important to try and search for these possible variables and to name them. When it comes to external validity, it needs to be said that this research cannot be generalized to all crisis situations and all fields of policy making on every governmental level.

It is wrong to assume that this specific crisis or organization is representative for all other governmental organizations or crises. However, this thesis may be able to make strategic

23 As I will illustrate in the methods below, the internal validity is guaranteed. This is because of the usage of existing frameworks, which have been applied before to other cases and has proven its face validity, for example in the case of Hudson’s framework on safety culture, from which the commercially used ‘Hearts and minds’ method was developed, as said in theoretical framework. However, one limitation is the external validity the used design and methods. While I make comparison between two time periods, it is hard to generalize the theory to all organizations confronted with a crisis. Safety culture theory shows to be adaptable for other organizations and to be able to generalize results, there needs to be proven causality. This thesis cannot rule out intervening variables as proving a causal link requires many cases for statistical significance. Therefore, the generalizability is limited to only this case or at best public defence organizations. However, this does not mean that the potential results are useless, because the thesis gives more insight for new research to further prove safety culture theory to be applicable to public defence organizations, in addition to hospitals, and oil and gas companies.

3.2 Research methods

24 For these reasons, I have chosen to employ the method of content analysis. What helps is that there are public documents, giving some detail on the crisis and what happened before, during, and after the crisis. While it does not provide a detailed inside look into the Dutch armed forces and the ministry, it does sketch a general picture of what happened. To avoid more biases and to guarantee some verifiability, I have chosen to go into four sources of information to reach triangulation between sources:

1. Debate transcripts and accompanying letters to the Dutch Lower House by the Minister

of Defence and the Minister of Social Affairs and Employment, who is also responsible for good working conditions (including the questions they were asked and their answers).

2. Media coverage between January 1, 2000 and June 8, 2018. These sources are found through the use of the LexisNexis system, and searching for chromium and the case of the Dutch armed forces. This provides a view of an increase or decrease in media attention, but also the content of what the media reported as the cause of the crisis. Journalists have their own sources and can find different facts or viewpoints that could

be overlooked with regular research.

3. Internal documents from the Dutch armed forces released publicly by the defence

ministry following the crisis, which date back to 1985.1 I only make use of the documents from 2000 until the most recent ones. It is not certain to what extent these documents are usable because they have been censored to some extent. It is also in the interest of the government not to release documents proving their responsibility for the crisis, but there could be information in the documents regarding the procedures and standards regarding safety and perhaps the processing of cases of exposure. The documents also include letters to the Dutch Lower House, reports by the Dutch labour inspection, Municipal Health Services and more of the documents mentioned in the next category.

4. Public reports and advice from the labour inspection, the Dutch Health Council, which

gives advice to the government regarding risks, and the Socio-economic Council. These reports help in reconstructing the timeline on what happened before and after the crisis,

1 To guarantee replicability and transparency of this thesis, a document containing an

overview of all published document and the full archive itself can be found at

https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/onderwerpen/chroomverf/documenten/publicaties/2014/10/30/al

25 but also context and the causes that were seen before the crisis, or if the services even noticed that there was a problem. Moreover, the Dutch labour inspection visited the workplaces from the crisis and some of the reports that have been published may give more information into what was going on. These reports can also be found in the internal documents from the Dutch armed forces, from which they are also partly sourced. Lastly, documents from the RIVM also give more insight into the context in which the research was done and what the results of this research is so far.

One complication is that the issue of chromium-6 goes back to before the 1980’s. The problem in this is that there are close to no sources available publicly for that period. Moreover, the other problem is that researching two big timeframes requires a significant amount of time and would jeopardize feasibility of this thesis. To solve this, the first period to be researched is limited to the year 2000 up until the crisis in June 2014. This was chosen because the earlier years may provide less material, because of archiving regulations and a possible lack of digitized documents but may also give insights into the regulation that was made up to the crisis

and possible signs of high levels of chromium-6. This is the case because most likely less attention was given to the problem, but also because a lot of older sources are not publicly available. The second period consists of June 2014, the moment of victims going public to the media and political debate, up to this day. Some of the research into the crisis is still going on, so even if media attention has decreased, the crisis is still formally being addressed. On June 4, 2018, the research on the use of paint containing chromium-6 at Prepositioned Organizational Material Storage (POMS) sites was completed. However, research is still being conducted on the use of paint containing chromium-6 and Chemical Agent Resistant Coating across all sites of the Dutch armed forces (Rijksoverheid.nl, 2018b, p. 3).

26 analyzed manually and sorted with Microsoft Word. Quotes are used in the analysis and translated from Dutch to English.

When it comes to operationalizing the theory in this thesis, both theories have already been operationalized to some extent in the theoretical framework, but the explanation below helps in further operationalizing the concepts to the level of observable codes in the operationalized coding scheme which can be found below.

Something which has to be mentioned about the safety culture theory by Hudson and his ‘Hearts and minds’ method is that the given scores are subjective and do not represent actual objective measurements of the safety culture (energyinst.org, 2006). This shows that safety culture is also a question of interpretation. However, this warning is given based on the subjective perception of people who are filling out the scorecards, the employees of the organization. Parker et al. (2006, p. 556) do recognize that cultures exist from more concrete aspects, but also abstract ones. Examples of concrete aspects are aspects on auditing safety within organizations and more abstract the views of cultures come from perceptions of the

workforce. While perceptions from individuals cannot be used as objective measurements, it is possible to estimate culture based on documents, which contain views of the workforce, management, but also the more concrete aspects.

For the measurement of the level of safety culture, I have chosen to make use of the earlier mentioned dimensions of safety culture and operationalized them using the description of Parker et al. (2006) of what every of the five levels of safety culture looks like when assessing the organizations safety culture. Every sub-code or indicator in the coding scheme below is a characteristic of the chosen dimensions at the level of each kind of safety culture.

27 perception of future risk and perceived managerial incompetence, which will be measured from the existing media articles. These measures are more aimed to look at the public concern, as Leiss (2003) sees that coverage influences these aspects from risk signals. These are defined by Burns et al. (1993, p. 614) as: “The degree to which people are at risk of experiencing harm from future hazards of this type” and “the degree to which the public beliefs that similar risks are measured incompetently”.

Lastly, there is the two types of pressure explained in SARF, while SARF does not explicitly name these are pressures which are necessarily political pressures, Gowda (2003) finds that actors put pressure on politicians for legislative change by making use of Kingdon’s agenda setting theory. I choose to make use of SARF to form a separate operationalization separate from SARF itself, because SARF formulates these results as secondary impacts together with political and social pressure but does not name the first two to be part of the larger process of pressuring that both Kingdon and Gowda describe. For this reason, I make use of SARF in that there is a focus on organizational change and regulatory change, but I do incorporate from Kingdon and Gowda that there are different actors involved in pressuring for

example politicians or the governmental administration. These pressures for legislative and organizational change are thus operationalized as regulatory pressure by inspections, experts or other actors, and Pressure for organizational change by politicians, inspections, experts or other actors.

28 Table 2. Operationalization of theory and coding scheme

Concept Code/dimension Sub-code/indicator Source

Safety culture Causes of accidents in eyes of management

(Cause of accident)

- The individuals directly involved, accidents perceived as part of the job (Pathological)

- People involved in accidents are removed, accidents are seen as bad luck (Reactive)

- Poor machinery and maintenance and

individuals, attempts to reduce exposure, still focus on individuals from management (Calculative)

- The whole system, management admits and

takes some blame (Proactive)

- Management accepts possible responsibility

after assessment, broad view of systems and individuals (Generative)

Parker et al. (2006, pp. 557-559)

Workers interest in competency / training (Interest in training)

- Only when a legal requirement, acceptance

of harsh working environment (Pathological)

- Training is aimed at attitude change after

accidents (Reactive)

- Standard training is given, and knowledge is tested, some on the job transfer of training (Calculative)

- Leadership sees importance of training, employees are proud to show their skills,

workforce themselves identify training needs (Proactive)

- Workforce show needs for training and

ways of getting it, training is more aimed at attitude and becomes a continuous process (Generative)

29 Worksite safety

management techniques (Worksite safety techniques)

- No techniques, people watch themselves

(Pathological)

- Use of hazard management technique after

accidents, no systematic use of it(Reactive) - Commercial techniques are used, and quotas

are used to prove it is working (Calculative) - Job safety analysis and observation are

accepted by workforce (Proactive)

- Job safety analysis is a continuous process,

people tell each other about hazards(Generative)

Parker et al. (2006, pp. 557-559)

Incidents/accidents reporting analysis (Reporting analysis)

- No reporting for lots of incidents,

investigation after serious incidents do not include human factors (Pathological) - Informal reporting system, focussed on

proving investigation took place, focus on finding guilty parties but no follow up (Reactive)

- Procedures producing a lot of data and

points of action, but opportunities are often not taken or restricted to workforce

(Calculative)

- Trained investigators who follow up, reports

are sent companywide to learn lessons (Proactive)

- Investigations show understanding of how accidents happen, based on information of past incidents, follow up checks if change if permanent (Generative)

30 Who checks safety on

daily basis?

(Daily safety check)

- No formal system, people take care of

themselves (Pathological)

- External inspection after major incidents,

site checks by management and supervisors (Reactive)

- Regular checks by management, not daily

and only to extent of compliance to procedures (Calculative)

- Encouragement to teams to check

themselves, managers walk around and engage employees in dialogue (Proactive) - Everybody is engaged in checking for

hazards, also for others, inspections are unnecessary (Generative)

Parker et al. (2006, pp. 557-559)

Audits and reviews

(Audits and reviews)

- Compliance with inspection requirements

and unstructured safety audits after accidents (Pathological)

- Unscheduled audits seen as punishment, but

seen as inescapable after accidents (Reactive)

- Regular scheduled structured audits in high

hazard areas, external audits unwelcome (Calculative)

- Extensive audits program welcoming

outside help, audits seen as positive (Proactive)

- Continuous search for problems, less

focussed on hardware systems and more on behaviours (Generative)

Parker et al.

31 Managements interest

in communicating safety (HSE) issues with workforce

(Management interest)

- Not interested apart from warning not to

cause problems (Pathological)

- Sending standard messages to workforce,

interest dies down over time (Reactive) - Information sharing and safety initiatives,

lot of talking but no bottom-up communication (Calculative) - Managers realise that dialogue with

workforce is needed, engage in asking and telling and looking out for each other (Proactive)

- Two-way transparent process with

management getting more information than sending out (Generative)

Parker et al. (2006, pp. 557-559)

Social

Amplification of Risk

Media coverage - Volume of stories (Not measured qualitatively)

- Repeating stories

Kasperson et al. (1988, p. 184)

Public perception / risk signal

(Public perception)

- Perception of managerial incompetence for similar risks (Managerial incompetence) - Perception of similar risks in the future that

may affect people (Future risk perception)

Leiss (2003, p. 367);

Burns et al. (1993, p. 621) Pressure for legislative- and organizational change

Political and social pressure

(Pressure)

- Regulatory pressure by politicians, inspections, experts or other actors (Regulatory)

- Pressure for organizational change by

politicians, inspections, experts or other actors (Organizational)

Gowda (2003); Kasperson et

32

Chapter 4: Case description

4.1 Policy and developments on chromium-6 paint between 2000 and June 2014

To be able to make the analysis of culture and the amplification of risk through media attention and public concern/perception, a statement of facts must be made to give insights into what events took place before and after the crisis coming to light. In the following parts, I will give a broad background of the events and context in which the analysis of all the courses regarding safety culture and public concern will be done.

The current legislation is part of a larger discussion which has been going on since the 1980’s, when the first signs of the toxicity and bad health effects of the chromium-6 metal came

to light. In the 1990’s, legislators paid more attention to working safely with chromium-6 when the defence ministry found in 1987 that workspaces were not safe for the use of chromium-6 (Stemerding, 2014). This led to new rules in 1998 after an advice from the Dutch National Health Council, as will be explained further on in this case description.

In 1998, the then State Secretary for Defence van Hoof, informed the Dutch Lower House that when measurements were made at the air base of Twenthe while planning for improvements of air circulation, over ten times the allowed amount of chromium-6 was found (Officielebekendmakingen.nl, 1998). Van Hoof recognized that the risks of working with hazardous materials was known for a long time, and that there would be a large-scale investigation into all the parts of the Dutch armed forces regarding chromium-6, as would there be a registration of employees who had worked with the paint. In 2001, van Hoof sent another letter to Dutch Lower House, giving an update on his previous letter (Officielebekendmakingen.nl, 2001). The letter said that while measures were taken to reduce exposure to chromium-6 at places where it was known that there would be exposure, these were not sufficient. In other places were research was done, there was no knowledge about the use of paint containing chromium-6 and thus no safety measures were taken. The armed forces had been looking to replace paint with chromium-6 for some time. The Royal Dutch Navy had been mostly free of chromium-6 at this point, as did the Royal Land Forces. The Royal Air Force

33 In 2001 the Ministry of Defence implemented new rules for working with chromium-6 when it became clear that employees were working with insufficient protection for years (de Vries, 2015). From this point on there were still several instances of going over the legal exposure limit of chromium-6. In 2008, employees were exposed to a high concentration of chromium-6 while spray painting helicopter parts which would not fit in the isolated spraying booth (de Vries & van der Parre, 2015). It was also found that the equipment was unsafe and would instead of filter spread chromium-6 through the worksite. In 2012, some of this equipment was replaced and worksites were cleaned in Volkel, when above limit levels of chromium-6 were found in samples.

In a scientific context, there was an understanding of the bad health effects of chromium-6 already around 1998 and 2001, when the Health Council pointed towards the studies which indicated that chromium-6 could harm unborn children or may damage human fertility (Gezondheidsraad.nl, 2001, p. 9). Based on this, the Health Council’s Committee for Compounds Toxic to Reproduction classified chromium-6 compounds to be a possible risk to human fertility. This shows that at that time there was some understanding that chromium-6

was not completely safe to humans. In 1998, the Health Council concluded that exposure to chromium-6 could lead to lung cancer, kidney failure, skin corrosion, insensitivity and irritation of respiratory systems and bowels (Gezondheidsraad.nl, 2016, pp. 15-16). Based on this conclusion, the Health Council declared all chromium-6 compounds to be carcinogenic, which asked for a worst-case scenario approach. This was incorporated in the advice for a legal limit of chromium-6. This limit was lowered even further after the socio-economic council gave advice in 2013 to further lower the allowed limit based on a European advice from 2004 which recommended lower limits.

For a long time, there have been developments going on pointing towards wanting to replace the usage of chromium-6. In 2015, The Minister of Defence Hennis stated that there was research going on into the replacement of paint with chromium-6, but later concluded that there was no approved non-toxic paint available that would meet the requirements of being able to replace the toxic paint (Defensie.nl, 2015a). As a part of the most recent policy, the usage of chromium-6 in paint is forbidden, unless there is no other alternative. This would lead to basic weapons systems, which requires paint containing chromium-6, to not be operational and put the national security in danger.

34 the court cases were employees of two specific workplaces in which the maintenance of NATO material was being conducted, called Prepositioned Organizational Material Storage (POMS) sites. This includes planes and tanks, which need new coating for chemical attacks, but most importantly, repairs on tanks or planes. With these tasks, victims claimed to be exposed to the paint through inhaling the paint particles after sanding down existing material which had received the paint or inhaling the fumes of new paint being applied (Rijksoverheid.nl, 2018d). The discussion around chromium-6 focusses primarily paint containing chromium-6, but also on the Chemical Agent Resistance Coating (CARC). Until the 1990’s, this coating contained chromium-6 which helps in preventing corrosion (Drost.nl, 2014). After not being heard in the courts, the victims moved to the media. In June of 2014, they spoke out against the Dutch armed forces, giving more insight into what they believed was that their exposure to these toxic metals was because of bad working conditions within the organization (Dagblad de Limburger, 2014a).

This legal battle went on after June 2014, as on May 17th, 2016, news came out that

victims were suing the defence ministry for the damages that were done to their health (Stoop, 2016). This is regarding employees of two specific work sites (Rijksoverheid.nl, 2016b). Other

parties are also suing the government when it comes to the exposure. On November 16th, 2016, 1limburg reported that a lawyer representing 3000 former employees of the two work sites was suing the Dutch government for damages, claiming that the Ministry of Defence was informed about the danger of chromium-6 and failed to act (Martens, 2016).

4.2 Background on events and developments after June 2014 until June 2018

This news of a large number of victims coming out to the media after not making process in the court system generates a fair amount of media attention, as the media had not heard of this story before. Initially, media coverage was about the problems that were brought attention to by the victims, after which more insight was given into the background of the toxic metal which was used in the paint.

35 On the 11th of November 2014 there was a debate in the Dutch Lower House with Minister of Defence Hennis (Stoop, 2014). Hennis before had to talk about previous incidents regarding the armed forces and media reported that Hennis was facing a harsh debate. In the debate, points were made on the question of what had happened, what was being done to help the victims, but also what would be done to address the problems with the armed forces. In reaction to the debate, Hennis took several actions:

1. Hennis temporarily shut down a small number of the POMS sites in which the paint was

being used and commissioned measurements by the Municipal Health Services of the workplaces in the specific municipalities to find out if the workplaces comply with the legal exposure limit of chromium-6 (Rijksoverheid.nl, 2018a).

2. The minister created a compensation scheme which awarded victims who claimed that they had become ill with an amount of money as preliminary compensation while awaiting further investigation. While this was done by Hennis to compensate former employees of the Dutch armed forces, there was a clear explanation that this compensation scheme did not imply an admission of guilt from the government. The

compensation is dependent on the category of the sickness that victims have, ranging from basic skin conditions to various forms of cancer. On the 16th of November 2016, around 200 people received compensation between 3000 and 15000 euros (Martens, 2016). As of January 2017, around 719 former employees had made a request for compensation, of which 456 had been rejected and 6 were still being processed (Rijksoverheid.nl, 2017c, p. 2).

3. Minister Hennis commissioned a large-scale investigation by the RIVM, which is

36 other conditions (Rijksoverheid.nl, 2017b). These results were used in the compensation scheme as a guideline for awarding compensation to victims.

The second pillar of the research by the RIVM consists of historical and survey research into what the causes were of the exposure happening, and second to research the extent to which the Dutch government is responsible for the exposure of employees of the Dutch armed forces to chromium-6 (Rijksoverheid.nl, 2016c, p. 2). This research was delayed because of its size, and the research methods now also included interviews instead of survey because the RIVM estimated that surveys would not give a great enough source of information about the context of what happened (Informatiepuntchroom6.nl, 2017). The guiding commission also gave the advice to include all other worksites in the research and not only the two where victims came from, after which the research was expanded to all POMS sites when it comes to the usage of CARC and all other locations of the armed forces when it comes to the usage of chromium-6, which Hennis agreed to (Rijksoverheid.nl, 2016a, p. 2).

What was not a formal action taken by Hennis, but what did come to light in the initial political debate, was the position of the leadership around the workplaces engaged in doing work with spray paint. Political concerns were about the supervisor over the workplaces in which the events took place. Hennis announced at first that a defence taskforce would research the complaints on the usage of chromium-6, and that this taskforce would be under the command of Freek Groen (Stoop, 2014). He is controversial because he was supervising the worksite for spray painting planes in Twente in the 80’s and 90’s, and repeatedly ignored complaints by employees who had worked with the paint containing chromium-6 and complaints from the labour inspection on unsafe working conditions. The main concern came from the Socialist Party, which argued that investigations could not be conducted objectively when the supervisor of the workplaces was also involved in (internal) investigations. Shortly after this, media reported that the commander had resigned from his function (Stoop, 2014).

37 governmental audit service found that employees were still working in unsafe conditions more recently and that the most basic stocktaking of risks was not handled, producing the question of how this could have happened. Minister of Defence Hennis explained that the recent finding of chromium-6 at the base of Eygelshoven was not to be concerned about because traces were found in two of the 210 taken samples at the base (Officielebekendmakingen.nl, 2015a, p. 11). In April of 2015, Hennis sent a letter to the Dutch Lower House explaining that the labour inspection of the armed forces will found unsafe conditions after they had done their quick-scan, recommending improvements. Similarly, the governmental audit service found that the safety department lacked personnel, had a lack of attention for risk management and itself needed more structural audits (Officielebekendmakingen.nl, 2015b, pp. 5-6).

On September 30th, 2016, the National Health Council published a new advice on the carcinogenicity of chromium-6 compounds, after a request from the Minister of Social Affairs and Employment asked the Health Council to revaluate their advice of safety levels of chromium-6 in perspective with the existing European and international rules (Gezondheidsraad.nl, 2016). This update was their newest advice on the carcinogenicity of

chromium-6 since 1998, but now included 16 years of extra scientific studies and based the estimation on recent humane studies which do not contradict each other. (Gezondheidsraad.nl, 2016, pp. 12-13, 26) The Health Council stressed that the carcinogenic classification has never been doubted over time, as the International Agency for Research on Cancer classified chromium-6 compounds to be carcinogenic in humans and animals in 1990, 2009 and 2012. Based on the wide range of studies, the Health Council estimated that the European classification of chromium-6 as carcinogenic is justified and made an advice in line with the European Chemicals Agency to further lower the legal exposure limit of chromium-6 to the Minister (Gezondheidsraad.nl, 2016, p. 26). The lower limit was made into law on October 18th, 2016 (Rijksoverheid.nl, 2017c).

38 company doctors and their own internal labour inspection (Rijksoverheid.nl, 2018b, p. 3). Until the 1990’s, there was no attention for the health risk of chromium-6. The report states that the

Ministry of Defence is liable for the damage caused to the health of employees exposed to chromium-6. At the same time, the national audit service published a report in which they found that the implementation of measures is behind on schedule, in that there is no plan to actively replace chromium-6 and the Dutch armed forces are not increasing their monitoring efforts (rijksoverheid.nl, 2018c, pp. 6-7). The service found that this was the case because line managers did not consider it to be a priority.

The guiding commission gave four recommendations (Rijksoverheid.nl, 2018b, p. 3): 1. To establish a compensation scheme for the victims of chromium-6.

2. To continue investing in aftercare for (former) employees. 3. Making an investment in prevention.

4. To continue the investigation into the use of chromium-6 at other locations, and the use of CARC with the Dutch armed forces.

The State Secretary for Defence Visser, accepted the recommendation and pointed towards measures that were already taken to prevent exposure and to care for employees. The reaction from victim to the research was negative, as they found out that to be eligible for the compensation between 5 and 40 thousand euros, their sickness has to be listed in the requirements, which differs from the earlier eligibility requirements for the compensation scheme (Gratama, 2018). The amount of compensation also depends on the position that the employee had, which means that a technical maintenance employee gets more than an administrative employee.