Companies To Fail--And How This

Influences Our Criteria

Primary Credit Analyst:

Michelle Brennan, London (44) 20-7176-7205; michelle.brennan@standardandpoors.com

Secondary Contacts:

Rodney A Clark, FSA, New York 212-438-7245; rodney.clark@standardandpoors.com Michael J Vine, Melbourne (61) 3-9631-2102; michael.vine@standardandpoors.com

Table Of Contents

Past Performance

Defaults Are More Commonly Triggered By Regulatory Responses Than

Debt Default

Liquidity

Liquidity Problems Prompted By Assets…

…And Reinforced By The Liability Structure

Underpricing And Under-Reserving Create Further Difficulties

Criteria Reponses

Catastrophe-Fueled Failures

Management And Governance Issues

How Reliable Is Intra-Group Support In Preventing Insurer Failure?

The Reasons for Failure Also Highlight The Reasons For Stronger

Creditworthiness

Fail--And How This Influences Our Criteria

As risk-bearing institutions, insurers can, and do, fail if risks are not managed adequately, even though the incidence of failure has in general been low. For this reason, it's worthwhile to look at the recurring issues that have caused, and still are causing, failures of rated and unrated insurers and explain how our observations inform our ratings criteria. When we refer to insurer failures, we are talking about company defaults, liquidations, or regulatory takeovers--or "near miss" situations where these would have occurred if the company had not received external support. In this article, we consider cases dating back as far as the 1980s because considering a shorter time frame of events can give an overly optimistic view of the strength of the sector. Since the 1980s, we have seen waves of failures that have informed our criteria developments, and have also influenced the way that many insurance companies are managed. In many cases of distress or failure that we have seen over this time, more than one of the following key factors was present, and often they reinforced each other:

• Poor liquidity management;

• Under-pricing and under-reserving;

• A high tolerance for investment risk;

• Management and governance issues;

• Difficulties related to rapid growth and/or expansion into non-core activities; and

• Sovereign-related risks.

Support--whether from another part of a group or from a government body--has, in our opinion, prevented the failure of several distressed insurance companies over the past decade. Assessing the likelihood of receiving such support is therefore a crucial feature of our rating methodology.

Overview

• Case history provides many examples of insurer failures caused by a select few recurring themes.

• These examples have informed our criteria over the past two decades--including our new insurance criteria published on May 7, 2013 -and, by contrast, highlight how insurers can achieve better creditworthiness.

• Liquidity issues spurred by problem assets and heightened by weak liability structures in times of stress have historically been a main cause of insurer failure.

• Even with improvements in how companies manage liquidity and reserving, management and governance issues continue to prompt insurance distress, and underpricing and managing rapid growth continue to be key risks.

• Group support has historically buoyed many insurers and remains a key component in the likelihood of failure.

• Those insurers most likely to run into difficulties lack the capitalization, prudent risk management, and solid underwriting and reserving strategies displayed by their more resilient peers.

On May 7, 2013, we published several new criteria articles for assigning ratings to insurance companies (see "Insurers: Rating Methodology," "Enterprise Risk Management," "Group Rating Methodology," and "Methodology For Linking Short-Term And Long-Term Ratings For Corporate, Insurance, And Sovereign Issuers," all published on

RatingsDirect). Parts of the new criteria address what we consider as the key causes of insurer distress, and include the expansion of country and risk analysis in our Insurance Industry And Country Risk Assessment (IICRA), an enhanced liquidity analysis, capital metrics that focus more on asset-liability risks, and the larger role for enterprise risk

management (ERM) for insurers with complex risks.

More idiosyncratic causes of failure, such as specific issues with management and governance, are the focus of our criteria for assessing the effectiveness of management and of risk management structures. In compiling our revised Group Rating Methodology, we considered cases where subsidiaries collapsed or where, in our opinion, they would have done so in the absence of group support.

Past Performance

Several periods of heightened stress spanning the past three decades, which resulted in an increased number of insurance company failures, inform our criteria. A number of these stress periods were more industry-specific than macroeconomic, although local economic conditions reinforced the Japanese situation outlined below, and sovereign distress led to the Russian example:

• 1984-1989: A number of predominantly casualty insurers in the U.S., including Mission Insurance Co. and Transit Casualty Insurance Co., became insolvent as loss reserves proved deficient following a period of inadequate pricing industrywide;

• 1992-1994: Several significant U.S. life insurers, including Executive Life Insurance Co., Mutual Benefit Life Insurance Co., and Confederation Life Insurance Co., failed due to a combination of illiquid asset concentrations and a lack of liquidity to meet maturing liabilities;

• 1999: The Russian Federation's selective default on some of its bonds led to severe pressure on the country's insurers holding these bonds, amounting to technical insolvency for some smaller insurers.

• 2000: Japanese life insurers, including Chiyoda Mutual Life Insurance Co., Kyoei Life Insurance Co., and Toho Mutual Life Insurance Co., voluntarily entered rehabilitation proceedings or closed their insurance business under regulatory order because guaranteed interest rates on savings products were no longer sustainable given low interest rates in Japan; and

• 2002-2005: Several international non-life insurers and reinsurers failed, including Mutual Risk Management Ltd., Trenwick Group Ltd., GLOBALE Rueckversicherungs-AG, and Converium Reinsurance (North America) Inc., predominantly due to deficient reserves for casualty lines following a period of inadequate pricing industrywide, compounded by weak risk management.

Perhaps surprisingly, the global financial crisis that began in 2007 failed to trigger a wave of life and non-life insurer defaults among rated companies. In fact, not one significant insurer that Standard & Poor's rated at the time (outside of the bond and mortgage insurance sectors) has defaulted due to the financial crisis. Insurers have defaulted or come under stress because of problems largely outside of their traditional insurance businesses (such as expansion into financial derivatives for American International Group Inc. [AIG]). Certain bond and mortgage insurers have also defaulted. However, these two sectors are outside the scope of the new insurance criteria (see "Bond Insurance Rating Methodology And Assumptions," Aug. 25, 2011, and "U.S. Mortgage Insurer Sector Outlook Remains Negative--And The Clock's Ticking," published on March 1, 2012).

Defaults Are More Commonly Triggered By Regulatory Responses Than Debt

Default

We observe that while corporate and bank failures are usually visible through the incomplete or untimely payment on all or some financial obligations, including debt restructurings, an insurance company failure most often becomes apparent when the regulator takes action because the insurer's financial position has become untenable. Standard & Poor's represents this by moving the issuer credit rating or insurance financial strength rating to 'R' (regulatory supervision), equivalent to a 'D' (default) in our ratings performance statistics. The timeliness element of obligations in insurance policies is typically much less clearly specified than for debt obligations. Also, insurers tend to have low debt burdens, but high policy obligations. So, nonpayment of a debt obligation generally isn't what prompts a default. In "Standard & Poor's Ratings Definitions", published June 22, 2012, we define an 'R' issuer credit rating as follows: "An obligor rated 'R' is under regulatory supervision owing to its financial condition. During the pendency of the regulatory supervision the regulators may have the power to favor one class of obligations over others or pay some obligations and not others." Following this regulatory intervention, an insurance company typically defaults on some or all financial obligations.

Liquidity

Insurance companies try to match maturity profiles of assets and liabilities. Yet, several insurance failures have arisen from concentrations in illiquid assets matched by liability structures that accelerated in a time of stress. Insurance operating companies traditionally have less risky liquidity structures than banks or certain types of corporates, but a large number of past failures are attributable to poor liquidity management. For example, a stream of U.S. life

insurance failures in the early 1990s (see table 1) reflected illiquid assets that could not meet liabilities that came due. The case was one of a "run on the bank" type scenario, where some customers looked to withdraw business from the companies due to concerns about their creditworthiness, which only served to reinforce the weaknesses.

Table 1

Asset Concentrations: U.S. Life Assurance Failures 1991-1994 First Executive Corp.

Executive Life Insurance Co. of CA First Capital Holdings Corp. Mutual Benefit Life Insurance Co. Monarch Life Insurance Co. Kentucky Central Life Insurance Co. Confederation Life Insurance Co.

Liquidity Problems Prompted By Assets…

In the case of Executive Life Insurance Company of New York, investments in high-yield bonds and hybrid capital securities lost market value and became less liquid on the secondary market. Mutual Benefit's illiquid investments were

predominantly real estate developments, including several intercompany loans. Real-estate equity investments also damaged the value and liquidity of Monarch Life's assets, and, in 1992, the insurer had to stop writing new life and annuity business. Around the same time, Kentucky Central and Confederation bore the brunt of large exposures to mortgage loans on commercial real estate, including construction loans on new developments and high loan-to-value mortgages, which performed poorly following the 1991-1992 U.S. recession.

Our capital model, introduced in 1994, has been refined over time to reflect experience of default rates on certain types of bonds and portfolio losses. One change, for example, was the increased loss experience data for commercial mortgages. The model applies substantial risk charges for speculative-grade bonds and for nonperforming real estate loans. Following the market downturn in 2007-2008, we introduced refined security-specific recovery analytics for certain parts of insurance investment portfolios, such as structured finance assets.

In 2012, we updated our capital model charges for commercial loan holdings of life insurers, adding greater differentiation by loan quality characteristics and applying a commensurate risk charge to construction loans. This change aims at identifying and taking into account risk in the loan portfolios before losses emerge.

The risk position factor within our new criteria framework takes account of the following heightened investment risks:

• Outsized asset concentrations by single obligor or asset class; and

• Outsized exposure to high risk assets.

In this way, we seek to reflect the potential for increased volatility beyond what is modeled for under our capital criteria.

…And Reinforced By The Liability Structure

These liquidity-related failures also highlighted to us the different ways in which certain types of policyholders react in times of stress. Withdrawal rates spike for certain types of products, and we reflected this in the adjustments that we made to our liquidity criteria (see below). In the case of the U.S. failures, the primary liquidity strains came from accelerated institutional Guaranteed Investment Contract (GIC) surrenders, while surrenders of fixed annuities and interest-sensitive life insurance provided secondary constraints.

Surrender rates can work against insurer creditworthiness in other ways, too. In Japan, low interest rates led to lower policy surrender rates, reinforcing the effect of negative product spreads that reduced life insurer profitability, and, in some cases, lowered solvency. While the problems encountered by Japanese life insurers were not due to liquidity per se, they do highlight how surrender rates can affect the viability of business models.

We introduced liquidity criteria for North American life insurers in 1994 and we have updated it on several occasions up to 2004, prior to the introduction of our new criteria in May 2013. Our criteria measures liquid assets against liquid liabilities, applies haircuts to reflect the risks associated with lower-rated bond holdings, and gives no credit for liquidity on commercial mortgages. The criteria also apply liquidity charges for institutional GICs that reflect the very high surrender risk.

U.S. insurance companies faced another round of liquidity-driven problems in 1999. Again, this was due to accelerating surrender demands, particularly on short-term GICs that were mainly invested in by mutual funds (see table 2). Table 2

Accelerating Surrender Demands: 1999 GenAmerica Financial Corp.

General American Life Insurance Co. ARM Financial Group Inc.

Integrity Life Insurance Co. RGA Reinsurance Co.

High Surrender Demands: Case Histories

In 1995, General American entered into an arrangement with Integrity Life Insurance Co., a unit of ARM Financial, whereby General American would distribute funding agreements designed by ARM and reinsure 50% of the funding agreement business to Integrity. Reinsurance Group of America Inc. (RGA) agreed to reinsure 25% of General American's retained risk under the funding agreement program. By 1999, the funding agreement business accounted for 95% of Integrity's insurance liabilities, demonstrating that risk concentration and the effect of rapid growth also contributed to the company's distress.

Due to a rise in interest rates, ARM's shareholders' equity decreased by about 50% between Dec. 31, 1998, and June 30, 1999. On July 29, 1999, the company announced that it would restructure its funding agreement business and seek a buyer. Surrenders on the funding agreements, which allowed investors (mainly sophisticated mutual funds) to put the funding agreements to the company with seven days' notice, increased significantly due to the announcement and subsequent lowering of the ratings on ARM. On Aug. 3, 1999, General American recaptured the reinsurance from Integrity, which forwarded $3.4 billion of liabilities and related assets onto General American's balance sheet.

On Aug. 10 the same year, General American was taken under administrative supervision by the Missouri Department of Insurance because of its inability to meet high surrender demands. On Aug. 20, a similar action was taken on Integrity by the Ohio Insurance Department at the company's request because of insufficient liquidity to meet its remaining obligations. RGA returned $1.4 billion of liabilities and $1.8 billion of assets to General American related to the funding agreement retrocession agreement, and other agreements related to its legacy as successor to the General American Reinsurance business. Metropolitan Life Insurance Co. (MetLife) stepped in to acquire both General American and RGA one week later.

We revised our liquidity criteria for life insurers in North America in 2000 because of these case histories to incorporate an assumption that any GIC that can be put to an insurer in less than 60 days will, in effect, be

immediately due. Any insurer currently issuing contracts with such features would, therefore, need to hold substantial liquid assets to be assigned an investment-grade rating by Standard & Poor's. In our new criteria framework, we have implemented a simplified version of the North American liquidity ratio for insurers other than North American life operating companies.

Underpricing And Under-Reserving Create Further Difficulties

In our observation, poor pricing strategies can lead to short-term business expansion at the expense of sustainable financial positions. Underpricing, for one, leads to negative business margins. The problem is compounded if poor pricing also leads to poor estimations of reserving needs, or if it compromises an insurer's capacity to reserve adequately for future claims.

We believe that poor policy design and pricing are the root of the issue, which are often by-products of insufficient experience in a particular business line and exacerbated by competitive pressures.

From California…

The case of the Californian workers' compensation market in the 1990s shows how aggressive market competitive dynamics can lead to a series of failures by encouraging prices and reserving that don't adequately reflect product risk (see table 3 for the resulting failures).

Table 3

The Impact Of Californian Workers' Compensation: 2000-2001 Symons International Group Inc.

Superior National Insurance Group Inc. Superior National Insurance Co. Reliance Group Holdings Inc. Reliance Insurance Co. of PA Fremont Indemnity Co. Legion Indemnity Co.

The state of California deregulated rates for workers' compensation in 1995, which was followed by a period of intense competition and drive for market share. The underpricing and inadequate reserving that ensued came to light late in the decade and resulted in several companies that were heavily concentrated in the market becoming insolvent. We responded to these events by fine-tuning our criteria so that it included a reserving model to identify reserving deficiencies. We also embedded into our methodology an increased focus on assessing policy features that could potentially lead to inadequate reserving. This included greater questioning of actuarial reports and identification of policy underpricing in several markets globally in the late 1990s and into the early 2000s. We continue to monitor this aspect today. For example, the IICRA, included in our new criteria, addresses emerging pricing pressures.

…To inadequate pricing and reserving globally

The turn of the century brought with it continuing pricing and reserving obstacles for insurers in certain markets globally.

Several U.K. life insurers displayed increased reserving needs following the market downturn in the early 2000s. This came as an upshot of the earlier underpricing of guarantees embedded into products and the overuse of equities to back policy liabilities. The only U.K. life insurance failure during this period, that of Equitable Life, was for reasons specific to the insurer, but the sector as a whole exhibited greater weakness for several years.

Globally, insurance companies failed due to industrywide underpricing in casualty lines and the resulting inadequate reserves (see table 4). The affected companies comprised primary insurers (Acceptance and Frontier) and reinsurers (Mutual Risk, Globale, Trenwick and PMA) that covered these lines. The case of the reinsurers was characterized by their expectation that they had provided very low risk financial or finite reinsurance services. These activities proved higher risk and this finally had to be offset by significant reserve strengthening, which ultimately rendered the companies insolvent.

Table 4

Underpricing And Reserving Problems: 2002-2004 Mutual Risk Management Ltd.

GLOBALE Rückversicherungs AG Trenwick Group Ltd.

Acceptance Insurance Cos. Inc. Acceptance Insurance Co. PMA Capital Insurance Co. Frontier Insurance Co.

Another example of an insurance company that was subjected to regulatory takeover following inadequate reserving was Singaporean Cosmic Insurance in 2002. Its strategy of soft pricing and reserving initially helped the company grow rapidly in its key competitive markets (motor and fire insurance and performance bonds). The strategy ultimately proved inadequate in the face of growing payments to policyholders, driven by court rulings on payments that were higher than anticipated. It experienced serious operational difficulties, including continued losses arising from higher claims, large uncollected premium balances, and inadequate loss reserves. Cosmic's demise was also spurred by an aggressive investment profile that was high in equities and by the concentration of its business lines. It did raise additional capital to strengthen its financial position, but the amount raised was insufficient to restore the regulatory solvency margin for its domestic insurance policies that the Insurance Act required it to maintain. Cosmic had to stop writing new business or accepting renewals in 2002.

In Taiwan, where the operating environment is highly competitive and most insurance companies are relatively small in capital size, two insurance companies have in the past decade been taken over by the regulator due to unsustainable financial positions. The first, Kuo Hua Insurance Co. Ltd., a non-life insurer, was taken over in 2005 because of its fragile capitalization. We had assigned a 'CCCpi' public information rating to the company in 2001, which we lowered to 'R' following the regulatory takeover.

The second, Kuo Hua Life Insurance Co. Ltd., was taken under regulatory control because of negative reported capital in 2009. Both companies had weak and deteriorating financial positions over a decade due to their small scale of operations and under-reserving issues. Kuo Hua Life also suffered a negative spread burden due to its asset-liability mismatch risks. We withdrew our 'CCCpi' ratings on the company in June 2004 because of insufficient public

information. Taiwanese life insurers' current profitability remains modest because of the weight of legacy-guaranteed products set against a backdrop of prolonged low interest rates.

The case of Japan

The collapse of Nissan Mutual Life, Japan's 16th-largest life insurer, in April 1997, showed that Japanese life insurance companies could fail. This bankruptcy, the first in the industry's history, triggered a loss of confidence, resulting in a sharp increase in surrenders for most insurers in the subsequent 12 months. Because no regulatory or industry scheme existed to protect policyholders, suspicions about the credibility of life insurers spread rapidly, particularly among ordinary individual policyholders. Subsequently, several then-rated insurers, including Chiyoda Mutual Life Insurance Co., Kyoei Life Insurance Co., and Toho Mutual Life Insurance Co., voluntarily entered rehabilitation proceedings or closed their insurance business under regulatory order. These failures were primarily the result of industry-wide afflictions. Japanese life business was being written at negative spreads, so insurers were taking on investment risk to compensate, creating higher risk profiles. High payout rates (typically of greater than 95%) were common and were used to support the mutual business models. However, they left insurers with thin balance sheets and inadequate capital resources.

Criteria Reponses

Our various criteria enhancements since these events aim to address the negative effects of market pricing and reserving dynamics in several ways. First is the IICRA, which takes account of industry underwriting standards and which could be adjusted to reflect poor market operating conditions. Our entity-specific assessments also address negative trends that affect only a segment of the market. As appropriate, our assessment of companies concentrated in a market sector that is experiencing tough competition or narrow-margin prices would likely include a negative

business risk profile (BRP) adjustment to reflect the risks associated with the competitive position, as well as a negative score for additional sources of capital volatility. This would weigh on the BRP and the financial risk profile (FRP), and therefore on the ratings.

The IICRA can also capture contributors to insurer distress such as distortionary legal restrictions on investments, government-imposed controls, and problems with the regulatory framework.

Catastrophe-Fueled Failures

Although certain insurance companies are exposed to specific catastrophes, such as floods and hurricanes, we have seen few failures due to the occurrence of such events. That said, ultimate losses may have been greater than insurers had anticipated.

One insurer that came near to failure following the terrorist attack on the World Trade Center (WTC) in 2001, was Japanese Taisei Fire & Marine Insurance Co. Ltd. The losses incurred exceeded Taisei Fire's capital such that it merged with Sompo Japan Insurance Inc. soon after, in December 2002. However, in our view, the distress at Taisei Fire cannot be solely attributed to the size of its exposure to a specific catastrophic event, but rather to the risk management issues that allowed such an exposure to build.

New Zealand's Christchurch and Canterbury region earthquakes in September 2010 and February 2011 were again unexpected, and therefore the effects on insurers would have been difficult to anticipate. The region is not considered

a traditional earthquake zone and, therefore, was not modeled by the industry to the sophistication of other identified catastrophe zones in New Zealand. Some insurers were therefore hit heavily by the cost of the earthquakes, due to their concentration in the region, the accumulation of multiple events in a short period, and inadequate reinsurance purchase.

Small entrepreneurial insurer Western Pacific Insurance Ltd. was placed into liquidation effective April 2011, because the cost of the multiple events exceeded its internal resources and reinsurance cover. Christchurch-based AMI Insurance Ltd. had its liabilities assumed by the New Zealand government under an ad-hoc government bailout, while the government-owned Earthquake Commission, which provides insurance against natural disasters in New Zealand, received government support (that had already been legislated for) because its liabilities exceeded its own substantial resources. Many insurers fortuitously benefited from group reinsurance covers purchased for larger exposures in Australia, without which local cover would have been insufficient.

Our criteria address exposure to catastrophe in the IICRA, as well as charges under our capital model methodology. Business and geographic concentrations, size constraints, and risk management and governance issues are assessed through the insurance criteria framework.

Management And Governance Issues

Overexposure to liabilities that were difficult to measure in advance (such as medical liabilities regarding asbestos) have certainly played a part in the downfall of some entities. But in our view, distress due to concentrated exposure is more often due to companies expanding into areas outside of their core competences. In these cases, liabilities were difficult for the companies to predict due to their risk management deficiencies.

Taisei Fire was a small Japanese fire and marine insurer that sought growth by expanding rapidly outside of its core domestic markets. But we understand it did not keep effective track of growing risk concentrations and used third parties to broker business, subject to delegated authorities. Some of these brokers exceeded their authority in terms of written cover, which is why such a large exposure to WTC risk was able to build up, unbeknownst to senior

management. The successor company subsequently sued to recoup money from some third parties, but in the meantime, Taisei Fire had lost its independence and had been forced to merge. Events such as this have led to the focus of our criteria on ERM and on assessing insurers' ability to manage complex business growth.

The importance of ERM, and management and governance, can be seen again in the case of Quinn Insurance Ltd., a general insurer, on which we did not have a rating. On March 30, 2010, following an application by the Central Bank of Ireland, the Irish High Court appointed joint provisional administrators to Quinn Insurance, due to what the regulator stated were "significant breaches" of regulatory solvency requirements. The solvency problems arose following large exposures to the collapsed Anglo Irish Bank, which were originally created through the use of financial transactions, known as contracts for difference, to build up a 28% equity stake in the bank. To us, this again highlights risk

concentrations as a main cause of distress. The regulator also had concerns over several guarantees provided by the insurance operations to the benefit of other non-insurance parts of the Quinn Group that reduced insurance assets. We believe this may be an indication that the group as a whole suffered from an inadequate risk management governance

framework.

In our view, risk management and governance issues regarding the insurance company's exposure to the broader business interests of the Quinn Group, allied with tight pricing and reserving, may have contributed to Quinn Insurance's problems. To us, a symptom of the risk management and governance weaknesses, and a cause of the pricing and reserving problems, was the company's lack of full-time in-house actuaries. The administrators' subsequent submission to the Irish Joint Oireachtas Committee on Finance and Public Expenditure highlighted several

loss-making underwriting and pricing scenarios within Quinn Insurance's business. These included total earned premiums of €93 million compared with total projected claims of €333 million for Professional Indemnity policies, and total premiums received of €114 million versus projected ultimate cost of claims of €149 million for its U.K.

commercial motor insurance business line.

The 2001 failure of Independent Insurance in the U.K. also reflected problems associated with rapid growth and inadequate governance, and ultimately fraud. Growth was achieved through underpricing, followed by under-reserving overseen by a dominant chief executive. The uncertainty surrounding the adequacy of reserves was exacerbated by claims that were suppressed from the company's systems, which in turn affected actuarial projections of claims development. Reinsurance irregularities were another problem. The company also had a history of price undercutting and reserving issues.

Independent Insurance suspended writing new business in June 2001 following discussions with the U.K. Financial Services Authority (FSA), after which, liquidators were appointed. Our criteria intend to capture some of the governance and expansion risks via our assessment of management and governance, ERM, and the competitive position. However, the fraud--for which the CEO and CFO served jail sentences--and its implications for reserving would remain difficult to detect. Our criteria do not seek to identify the existence of fraud because our analysis does not constitute a due diligence or audit. Instead, our analysis aims to identify situations where weak controls or governance issues create the potential for risks to occur.

AIG is yet another insurer that came very close to the point of collapse in 2008, due to expansion outside its areas of competence, coupled with rapid growth. Its diversification into quasi-banking was compounded by governance and ERM issues. In our view, AIG found it difficult to develop an appropriate valuation approach for certain parts of its portfolios, and this had implications for reserving and capitalization.

Serial acquisitions and overexpansion

Several insurance companies have failed or come close to failure due to business models that encouraged

overexpansion, stretching risk management capabilities and financials alike. Examples include the Conseco group, now known as CNO Financial, which suffered from risks it inherited when it acquired other companies, including consumer finance.

The 2001 collapse of Australian group HIH Insurance Ltd. was one of the most notable cases of overexpansion, having grown through acquisitions, and organically, to become the second-largest insurer in Australia in 20 years. In addition to having exposures to the aggressively competitive Californian workers' compensation market discussed earlier, the company had also grown under a dominant and entrepreneurial management style, aggressively chasing new business. Reserving became thinner as the company grew in confidence about the superior quality of its approach. The business

model for growth was also biased toward the opportunity for investment market earnings from an enlarged premium base, rather than a focus on quality underwriting earnings. Further detriment arose from distribution being over-reliant on ratings-sensitive broker business. Cash flow issues contributed to a fall-off in broker business and difficulties in selling subsidiaries to raise cash. In our view, HIH's collapse highlighted the importance of ERM, competitive position, and our capital analysis in assessing the risks of such a group.

The Scottish Re Group also developed a leveraged growth model with a pattern of overpaying for acquisitions. This led to its near-failure and, in early 2008, it ceased writing new business and notified its clients that it would not accept any new reinsurance risks under existing reinsurance treaties, thereby placing its remaining treaties into run-off.

Our criteria capture such risks more specifically by refinements to our ERM criteria, and our refined capitalization and competition assessments.

The Case of Equitable Life--Reserving, pricing and management

U.K.-based life insurer The Equitable Life Assurance Society (Equitable Life) defaulted under our criteria in February 2002. This followed the restructuring of Equitable Life's liabilities between guaranteed annuity rate (GAR) and non-GAR policyholders. Under our criteria, this restructuring was a default by the society on some of its contractual obligations to policyholders, notably the GAR policyholders, akin to a distressed exchange. A court ruling requiring Equitable Life to comply with specific guarantees embedded in certain policies--despite the severe financial hit this had dealt on other policyholders--prompted the restructuring. While the failure of Equitable Life could narrowly be

attributed to the unexpected court ruling, we believe it could more broadly be attributed to inefficient pricing and reserving of guaranteed products, coupled with limited financial flexibility under its business model.

Our criteria do not seek to identify specific unexpected legal risks but are intended to point out high-risk lines of business and, via our ERM criteria, cases where an insurer does not address the broader risks associated with product design. Such guaranteed products would also require substantial backing under our refined capital model.

How Reliable Is Intra-Group Support In Preventing Insurer Failure?

Group membership can sometimes prevent an insurer's failure because an entity can receive support from stronger group members in times of need. But with these benefits come added risk. Sometimes a parent or sister company can weaken a subsidiary's position and contribute to distress. For example, Monarch Life Insurance Co.'s franchise was damaged by reputational problems at its holding company. Irish Life Assurance PLC's financial strength was damaged by the performance of its banking subsidiary to such an extent that the Irish government acquired a 99% stake in the group in 2011, and then proceeded to dismantle the group to insulate the insurer from the banking risks.

In some cases, group support may fail to materialize or a parent may decide to divest a subsidiary. Examples of divestments include Zurich Insurance Co. Group's spin-off of its reinsurance operations, Converium AG; Citigroup Inc.'s spin-off of its non-life insurance operations, Travelers Property Casualty Insurance Co.; and Chubb Corp.'s divestiture of its subsidiary, The Chubb Life Companies.

potential of group membership damaging or benefiting a subsidiary's creditworthiness. We also use it to evaluate the relative likelihood that certain types of subsidiaries will be supported in a time of stress.

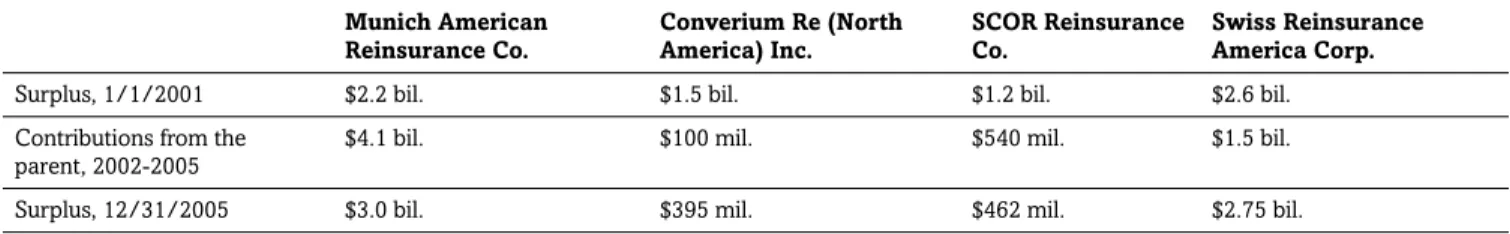

Table 5 shows companies that were all in the same situation as the companies in Table 4, the only difference being that they had parent companies in Europe that provided capital to U.S. subsidiaries. In the cases of the first three, the U.S. subsidiaries would have been severely impaired without their parents' contributions. SCOR Reinsurance Co. raised over a billion euro to avoid damage to the entire group. Swiss-based Converium chose to place its U.S. subsidiary into run-off, however, and ceased to add additional capital, leading to the subsidiary's eventual insolvency in 2004. Table 5

Subsidiaries And The Impact Of Underpricing And Reserving: 2002-2005

Munich American Reinsurance Co.

Converium Re (North America) Inc.

SCOR Reinsurance Co.

Swiss Reinsurance America Corp.

Surplus, 1/1/2001 $2.2 bil. $1.5 bil. $1.2 bil. $2.6 bil.

Contributions from the parent, 2002-2005

$4.1 bil. $100 mil. $540 mil. $1.5 bil.

Surplus, 12/31/2005 $3.0 bil. $395 mil. $462 mil. $2.75 bil.

Since 2000, we have also seen several European parents support their European subsidiaries. The support several U.K. banks provided to their life insurance subsidiaries boosted solvency levels in the wake of overexposure to equities and underpricing of embedded guarantees. For example, Abbey National PLC pumped several capital injections into its subsidiaries Scottish Mutual Assurance PLC and Scottish Provident Ltd. in 2002 and 2003.

It is our opinion that a parent company will likely try to provide support to distressed subsidiaries operating in markets that are most important to the group's franchise. This may involve overlap in customers, product lines, or geographic markets. Furthermore, such support may be provided to avoid reputational damage to the parent due to common branding or the impact on the parent's strategy. For example, AXA Group injected Turkish lira (TRY) 770 million into its Turkish subsidiary, AXA Sigorta A.S., in the first quarter of 2013 to compensate for the subsidiary having incurred material losses accounting for 97% of total 2011 shareholders' equity. The much-needed boost restored capital for the first quarter of 2013 to marginal levels. In our view, this support was due to the importance of the Turkish market to the group both in terms of strategy and reputation.

It seems to us however, that parents are less likely to provide support when the subsidiary is more peripheral and less crucial to the group's strategy and reputation. Gerling's decision in 2003 to not pay under the terms of a guarantee the coupon of the subordinated notes issued by Gerling Global Finance Alpha B.V. stands out as an obvious example. In our view, refusing to pay under the guarantee amounted in effect to Gerling deciding that the cash that would

ordinarily have been used to service the interest payment on the notes that it guaranteed, could be put to better use by supporting the orderly run-off of its obligations to policyholders. Parents are also understandably reluctant to support their subsidiaries when the required capital injection would be too great for the group to bear.

A parent company may also reassess its subsidiary as less strategically important when the parent's core market becomes trickier to navigate.

the degree of insulation a subsidiary may have from potential distress elsewhere in the group, which may support a higher rating than for other group companies. In the case of HIH Insurance Ltd., trustee-type protection mechanisms for the New Zealand subsidiary supported a higher rating on it than was assigned to its parent, because the local protections restricted dividend flows to the parent. This ratings differential prior to liquidation has proved appropriate, in our view, given that New Zealand policyholders subsequently received payment of claims in full, and the business was ultimately sold as a going concern to QBE Insurance Group Ltd.

These experiences inform our criteria for assessing the group status of insurance subsidiaries of financial services groups because we see them as affecting the likelihood of such subsidiaries failing.

Why extraordinary government support doesn't typically prevent insurer failures

Government intervention to prevent an insurer failure is rare. Usually, a government will become involved only to facilitate an orderly run-off or closure, which does not prevent a default. Even when governments do intercede, for example, when the Irish government supported both Insurance Corporation of Ireland (ICI) and Private Motorists Protection Association (PMPA) in the 1980s, there is no certainty that the insurer will receive full support in future times of stress. The Irish authorities decided to place Quinn Insurance into administration in March 2010, which was followed by a restructuring of the group's debt in 2011.

In our opinion, generally governments have only intervened when an insurer's failure would have had systemic implications for a country's banking system. For example, we view that the U.S. government supported AIG to avoid the damage its failure would have caused to the banking system as a whole. Similarly, the local systemic importance of ING Groep's banking operations provided the impetus for the Dutch government to ensure that it did not come under stress. The Irish Government decided in 1985 to buy the failing ICI, which had reserving shortfalls, to bail out the highly systemically important bank owner, Allied Irish Banks. We recognize that some insurers are likely to be considered global systemically important financial institutions (G-SIFIs) under future regulatory initiatives, but we don't believe that this classification would increase the likelihood of government support to bail out creditors. We rarely raise insurer ratings to reflect the potential for extraordinary government support. The exceptions are government related entities (GREs) that have specific policy roles and government links that lead to such support. Classification as a GRE reflects our opinion of the importance of the entity's role to the government, due to the severity of the effects that a default would have on the government or the local economy. The classification also looks at the strength and durability of the links between the government and the entity, including the government's track record of providing support. Examples include French Caisse Centrale de Réassurance (CCR) and Morocco-based reinsurer Société Centrale de Réassurance (SCR), both of which are assessed as GREs with an "almost certain" likelihood of extraordinary government support.

Sovereign-related stresses

In our view, sovereign distress creates profound financial and operating problems for local insurers. They can swiftly trigger failures, even when insurers have otherwise been managed wisely. The state of the economy influences business volumes and claims experience, while investment markets affect an insurer's balance sheet strength. For example, falling values of sovereign bond holdings can affect solvency, as seen in the recapitalization needs of some insurers following the 2012 Greek sovereign debt restructuring and in the pressures some Russian insurers faced in

1999. Profitability also suffers when households and businesses confront more precarious conditions.

A case in point is the 2001-2003 Argentine sovereign debt crisis, which had multiple repercussions on insurers. These included:

• A severe impact on liquidity, due to the restructuring of their Argentine domestic sovereign debt exposure, and a bank deposit freeze;

• Temporary restrictions in making foreign currency payments to offshore reinsurers, due to exchange controls; and

• A significant impact on saving products, including life insurance and annuities, due to the loss in value to consumers when the government forced policies to convert from dollars to Argentine pesos at below-market rates.

This latter event persuaded local investors to move away from these products, which in turn led to premiums falling for personal insurance products by 50% between 2001 and 2003, and by 30% for non-life products during the same period. At the same time, there was a sharp hike in claims, mostly due to voluntary retirement insurance (related to high unemployment levels), putting greater pressure on profitability.

As a result of the Colombian sovereign debt crisis of 1997-1999, 10 Colombian insurers were liquidated or acquired between 1999 and 2001. Profitability had dropped by more than 50% at the sector level, with the overall industry experiencing net losses.

We take account of sovereign-related links via our IICRA framework and also through our criteria for considering whether an insurer can be rated at a higher level than the sovereign of its country of domicile. We believe that insurers can in certain circumstances survive a sovereign default without themselves defaulting. But we also believe that sovereign distress weakens the creditworthiness of local insurers and the imposition of sovereign controls and restrictions limits their operations.

Insurers are typically not exempt from the effect of any deposit freeze or capital controls that may spring from a sovereign debt crisis, and this can prevent them from timely and full payment of obligations. In March 2013, for instance, Cypriot insurers were subject to the government-imposed "bail-in" of certain bank deposits, and they're also affected by current restrictions on bank account withdrawals and controls on cross-border transactions. In our view, this can affect an insurer's ability to service its obligations and meet contractual policy redemptions. (Standard & Poor's does not have any ratings on Cypriot insurance companies.)

Other sovereign-related risks include direct government intervention of a severity that may interfere with the value or enforceability of parent policyholder guarantees, particularly in the case of forced currency redenomination or

exchange controls. For example, the abovementioned forced conversion of U.S. dollar denominated policies into pesos during the Argentine debt crisis. Insurers 'pesified' their U.S. dollar policies at exchange rates of either 1.4:1 or 1:1 (pesos to U.S. dollars), when the market rate was about 2.3, imposing a considerable loss in value for the consumer. Given the requirements of the legislation and related domestic court rulings, guarantees from non-Argentine parent companies were not considered fully enforceable to enable full payment of obligations in the original currency. This is why, in accordance with our methodology, when a subsidiary insurer benefits from a policyholder guarantee from elsewhere in its group, the rating is the lower of either:

• The result from adding six notches to the local currency sovereign credit rating if it is 'BBB-' or higher; or

• The result from adding four notches to a local currency sovereign credit rating that is 'BB+' or lower.

These caps on the rating outcome are in place because we have observed that guarantees and support arrangements can be overridden in certain cases, based on the nature of sovereign intervention during crises. In particular, domestic court rulings may prohibit enforcement of the support arrangement or guarantee at a value equivalent to the original terms.

The Reasons for Failure Also Highlight The Reasons For Stronger

Creditworthiness

In our view, past insurer failures and distress also indicate how insurers can attain stronger creditworthiness, and have informed the criteria that lead to higher ratings reflecting stronger features. The insurers that performed best in times of systemic stress, and that avoided the pitfalls to which some failed insurers succumbed, share notable common attributes. Robust franchises, solid liquidity management, and good capitalization are all characteristics of the most resilient insurers. These companies also display strong underwriting and reserving policies, competitive cost structures and investment returns, and prudent risk management structures and risk appetite. They are adept at using their technical expertise to build competitive advantage, and, in some cases, they benefit from access to potential financial support. While insurers may not be able to control all risks in their operating environment--some sovereign-related risks, for example--we believe that those companies most likely to fail are those that don't recognize and address the risks that can be managed.

Related Criteria And Research

• Standard & Poor's Ratings Definitions, May 30, 2013

• Request For Comment: Ratings Above The Sovereign--Corporate And Government Ratings, April 12, 2013

• S&P's Insurance Industry And Country Risk Assessments Offer A Global View Of The Forces Shaping Insurance Markets, May 22, 2013

• Insurers: Rating Methodology, May 7, 2013

• Enterprise Risk Management, May 7, 2013

• Group Rating Methodology, May 7, 2013

• Methodology For Linking Short-Term And Long-Term Ratings For Corporate, Insurance, And Sovereign Issuers, May 7, 2013

• Rating Government-Related Entities: Methodology And Assumptions, Dec. 9, 2010

• Nonsovereign Ratings That Exceed EMU Sovereign Ratings: Methodology And Assumptions, June 14, 2011

• Rating Implications Of Exchange Offers And Similar Restructurings, Update, May 12, 2009 Additional Contact:

S&P may receive compensation for its ratings and certain analyses, normally from issuers or underwriters of securities or from obligors. S&P reserves the right to disseminate its opinions and analyses. S&P's public ratings and analyses are made available on its Web sites,

www.standardandpoors.com (free of charge), and www.ratingsdirect.com and www.globalcreditportal.com (subscription) and www.spcapitaliq.com (subscription) and may be distributed through other means, including via S&P publications and third-party redistributors. Additional information about our ratings fees is available at www.standardandpoors.com/usratingsfees.

S&P keeps certain activities of its business units separate from each other in order to preserve the independence and objectivity of their respective activities. As a result, certain business units of S&P may have information that is not available to other S&P business units. S&P has established policies and procedures to maintain the confidentiality of certain nonpublic information received in connection with each analytical process. To the extent that regulatory authorities allow a rating agency to acknowledge in one jurisdiction a rating issued in another jurisdiction for certain regulatory purposes, S&P reserves the right to assign, withdraw, or suspend such acknowledgement at any time and in its sole discretion. S&P Parties disclaim any duty whatsoever arising out of the assignment, withdrawal, or suspension of an acknowledgment as well as any liability for any damage alleged to have been suffered on account thereof.

Credit-related and other analyses, including ratings, and statements in the Content are statements of opinion as of the date they are expressed and not statements of fact. S&P's opinions, analyses, and rating acknowledgment decisions (described below) are not recommendations to purchase, hold, or sell any securities or to make any investment decisions, and do not address the suitability of any security. S&P assumes no obligation to update the Content following publication in any form or format. The Content should not be relied on and is not a substitute for the skill, judgment and experience of the user, its management, employees, advisors and/or clients when making investment and other business decisions. S&P does not act as a fiduciary or an investment advisor except where registered as such. While S&P has obtained information from sources it believes to be reliable, S&P does not perform an audit and undertakes no duty of due diligence or independent verification of any information it receives. thereof (Content) may be modified, reverse engineered, reproduced or distributed in any form by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of Standard & Poor's Financial Services LLC or its affiliates (collectively, S&P). The Content shall not be used for any unlawful or unauthorized purposes. S&P and any third-party providers, as well as their directors, officers, shareholders, employees or agents (collectively S&P Parties) do not guarantee the accuracy, completeness, timeliness or availability of the Content. S&P Parties are not responsible for any errors or omissions (negligent or otherwise), regardless of the cause, for the results obtained from the use of the Content, or for the security or maintenance of any data input by the user. The Content is provided on an "as is" basis. S&P PARTIES DISCLAIM ANY AND ALL EXPRESS OR IMPLIED WARRANTIES, INCLUDING, BUT NOT LIMITED TO, ANY WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY OR FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE OR USE, FREEDOM FROM BUGS, SOFTWARE ERRORS OR DEFECTS, THAT THE CONTENT'S FUNCTIONING WILL BE UNINTERRUPTED, OR THAT THE CONTENT WILL OPERATE WITH ANY SOFTWARE OR HARDWARE CONFIGURATION. In no event shall S&P Parties be liable to any party for any direct, indirect, incidental, exemplary, compensatory, punitive, special or consequential damages, costs, expenses, legal fees, or losses (including, without limitation, lost income or lost profits and opportunity costs or losses caused by negligence) in connection with any use of the Content even if advised of the possibility of such damages.