Parent Attitudes and Preferences for

Discussing Health Care Costs in the

Inpatient Setting

Jimmy Beck, MD, MEd,aJulia Wignall, MA,bElizabeth Jacob-Files, MA, MPH,aMichael J. Tchou, MD,cAlan Schroeder, MD,d Nora B. Henrikson, PhD, MPH,eArti D. Desai, MD, MSPHa

abstract

OBJECTIVESTo explore parent attitudes toward discussing their child’s health care costs in the inpatient setting and to identify strategies for health care providers to engage in cost discussions with parents.

METHODS:Using purposeful sampling, we conducted semistructured interviews between October

2017 and February 2018 with parents of children with and without chronic disease who received care at a tertiary academic children’s hospital. Researchers coded the data using applied thematic analysis to identify salient themes and organized them into

a conceptual model.

RESULTS:We interviewed 42 parents and identified 2 major domains. Categories in thefirst domain related to factors that influence the parent’s desire to discuss health care costs in the inpatient setting, including responsibility for out-of-pocket expenses, understanding their child’s insurance coverage, parent responses tofinancial stress, and their child’s severity of illness on hospital presentation. Categories in the second domain related to parent preference regarding the execution of cost discussions. Parents felt these discussions should be optional and individualized to meet the unique values and preferences of families. They highlighted concerns regarding physician involvement in these discussions; their preference instead was to explorefinancial issues with afinancial counselor or social worker.

CONCLUSIONS:Parents recommended that cost discussions in the inpatient setting should be

optional and based on the needs of the family. Families expressed a desire for physicians to introduce rather than conduct cost discussions. Specific recommendations from parents for these discussions may be used to inform the initiation and improvement of cost discussions with families during inpatient encounters.

WHAT’S KNOWN ON THIS SUBJECT:Health care costs can place a significantfinancial burden on families. Studies suggest that many adult patients wish to discuss medical costs with physicians; however, little is known about the cost discussion preferences of parents when a child is hospitalized.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS:Parents recommended that cost discussions should be optional and based on individual family needs. They prefer to have physicians introduce rather than conduct cost discussions. We provide a framework for how to have cost discussions in the inpatient setting.

To cite: Beck J, Wignall J, Jacob-Files E, et al. Parent Attitudes and Preferences for Discussing Health Care Costs in the Inpatient Setting. Pediatrics. 2019;144(2): e20184029

aDepartment of Pediatrics, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington;bCenter for Child Health, Behavior and

Development, Seattle Children’s Hospital, Seattle, Washington;cDepartment of Pediatrics, School of Medicine,

University of Colorado and Children’s Hospital Colorado, Aurora, Colorado;dDepartment of Pediatrics, School of

Medicine, Stanford University, Stanford, California; andeKaiser Permanente Washington Health Research

Institute, Seattle, Washington

Dr Beck, Ms Wignall, and Ms Jacob-Files conceptualized and designed the study, coordinated data collection, conducted the qualitative analysis, and drafted the initial manuscript; Drs Tchou, Schroeder, Henrikson, and Desai conceptualized and designed the study and assisted with the development of the conceptual model; and all authors reviewed and revised the manuscript, approved thefinal manuscript as submitted, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

DOI:https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2018-4029

Medical bills are a leading cause of

financial harm, often leading to foreclosed homes, depleted savings, and bankruptcy.1–3Thisfinancial burden is associated with poor health outcomes and reduced quality of life.4Researchers have sought to understand patients’perspectives on cost discussions, revealing that most adult patients wish to discuss costs with their physicians, regardless of insurance type.5–8Despite this, ,20% of patients report discussing treatment costs with their

physician.9–11

Pediatric health care in the United States represents 1 of the fastest growing areas of health care costs. Hospitalization accounted for 30% of the total $233 billion spent on health care expenditures for children in 2012.12Children with medical complexity account for the largest proportion of these expenditures,13,14 and the impact on families of this increasingfinancial burden remains poorly understood within the pediatric literature. The literature reveals that parents’ decision-making processes differ when acting as a proxy for their child than when representing themselves in a similar situation.15As such, it is possible that similar discrepancies may also be present in cost decisions; hence, research used to specifically examine the perspectives of parents rather than patients is needed.

A 2012 American Academy of Pediatrics policy statement on patient- and family-centered care16 outlined core principles to guide the delivery of health care, including

“sharing complete, honest, and unbiased information with patients and their families…so that they may effectively participate in care and decision-making to the level they choose.”Currently, little is known about parent or guardian (hereafter referred to only as parent)

preferences for incorporating discussions about medical costs in

the shared decision-making process. Furthermore, authors of few studies explore the role of cost discussions for hospitalized patients.16

Our objectives with this study were to (1) explore parent attitudes toward discussing their child’s health care costs in the inpatient setting and (2) identify strategies and scripts for health care providers (HCPs) to engage in these cost discussions with parents.

METHODS

Study Population and Design

We conducted a qualitative study from October 2017 to February 2018 at a university-affiliated freestanding children’s hospital. We chose a qualitative approach to provide a formative, in-depth exploration of parents’attitudes and preferences given the paucity of available information on this topic.17

Using purposive sampling, we recruited English-speaking parents of children in 2 groups (those with children with chronic conditions and those with children without chronic conditions) to maximize the range of perspectives in our sample. Parents of children with chronic conditions were identified from the family advisory council, which comprises parents of children with complex chronic conditions (eg, quadriplegia) or noncomplex chronic conditions (eg, type 1 diabetes). Parents from the council were recruited via e-mail by using convenience sampling. We verified the child had a chronic condition by asking the parent at the beginning of the interview. Additionally, only parents of children who were currently hospitalized or hospitalized at least once in the past year were eligible to participate. Parents of children without chronic conditions (eg, children with no previous admissions who were admitted for bronchiolitis or pneumonia) were identified from

a convenience sample of patients hospitalized on the general medical service. We verified the child did not have a chronic disease by chart review and by asking the family. We enrolled parents of patients with an inpatient stay of$2 days to ensure parents had sufficient time to interact with a variety of HCPs.

Data Collection

Using previously developed definitions of cost in discussions with families (eg, out-of-pocket medical costs, insurance coverage, and costs to the health care system or society),18we developed a semistructured interview guide focused on parent preferences around cost discussions. For example, we asked parents if they remembered having discussions about cost during any of their hospitalizations.“Cost”was defined as either the direct cost of

a medicine, test, or imaging study or the parent’s out-of-pocket medical costs such as copayments and deductibles. We pilot tested the interview guide with 6 parents and revised it to optimize comprehensiveness and

understandability (Supplemental Fig 2, interview guide).

Next, 1 of 2 research team members (J.B. or J.W.) conducted interviews with eligible parents either in person or by telephone. Written informed consent was obtained from each of the participants immediately before conducting the interview.

perspectives.19Participants also completed a demographic survey at the conclusion of the interview. Participants were not compensated for their time. Because data analysis occurred concurrently with data collection, we recruited and enrolled parents until the identified themes captured the majority of

perspectives elicited from interviews.

All study procedures were approved by the Seattle Children’s Hospital Institutional Review Board.

Data Analysis

We analyzed interview data using applied thematic analysis.20 Three research team members (J.B., J.W., and E.J.-F.) read and open-coded thefirst 3 transcripts, eliciting broad concepts that informed an initial draft of the codebook. Two of the researchers then

independently coded subsequent transcripts with the third, resolving disagreements. Meeting weekly, we initially modified the codebook to clarify code definitions and accommodate the identification of new codes. Once solidified, we focused on categorizing themes into major domains with monthly feedback from the full research team, leading to the development of a conceptual model. Data analysis was facilitated by using Dedoose (version 7.0.23; SocioCultural Research Consultants, Los Angeles, CA).

RESULTS

Demographics

For the chronic sample, 110 parents were approached from the Seattle Children’s Family Advisory Council and 20 responded to the invitation to participate and were interviewed. We recruited and conducted interviews of parents of children without a chronic condition on 10 separate days. For the nonchronic sample, a total of 87 parents met our

eligibility criteria and 28 were approached, with 6 parents declining to participate. Most of the 42 parents who agreed to participate in our

study were white, reported an annual household income of ,$99 000, and were evenly divided between having public or private TABLE 1Demographic Characteristics of the Study Sample (N542)

Characteristic n %

Parent group

Children with chronic conditions 20 47

Children without chronic conditions 22 53

Parent age, y

21–30 10 24

31–40 14 34

41–50 18 43

Sex

Female 20 48

Male 22 52

Race

White 18 43

African American 5 12

Hispanic 7 17

Asian American 2 5

Preferred not to answer 10 24

Highest education level

Some high school 2 5

High school or GED 7 17

Some college 16 38

College degree 10 24

Preferred not to answer 7 17

Annual household income, $

,50 000 10 24

50 000–99 000 19 45

100 000–149 000 8 19

.150 000 5 12

Primary insurance

Medicaid 17 40

Employer based 14 34

Employer based, high deductible 8 19

Other (individual policy, Armed Forces) 3 7

On a scale of 1–10, how comfortable are you with your child’s insurance coverage (1 being not comfortable at all, 10 being extremely comfortable)

Children with chronic conditions 8.3 N/A

Children without chronic conditions 5.6 N/A

Do you know your child’s health insurance copay (if applicable)?

Yes 31 74

No 11 26

Do you know your child’s health insurance deductible (if applicable)?

Yes 26 62

No 14 34

Unsure 2 5

In the past 12 mo, have you delayed seeking medical care for your child?

Yes 5 12

No 37 88

In the past 12 mo, have you had trouble paying medical bills for your child?

Yes 18 43

No 24 57

How are you managingfinancially these days?

Difficult 8 19

Just getting by 9 21

Doing okay 12 29

Comfortable 13 31

insurance for their child. Parent demographic characteristics are shown in Table 1. Interviews lasted an average of 40 minutes (range: 28–66 minutes).

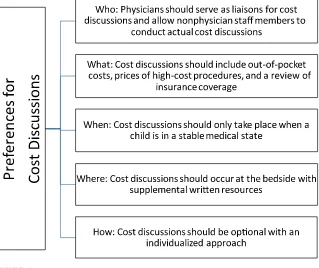

Conceptual Model

Themes from our analysis fell into 1 of 2 domains that were consistent with our study objectives. In the

first domain, we identified 4 factors that related to the parent’s desire for discussing their child’s health care costs in the inpatient setting. In the second domain, parents elucidated their preferences for cost discussions, which we grouped into 5 categories: who, what, when, where, and how (Fig 1). Overall, parents from both

groups shared similar perspectives, with the exception of their

recommendations regarding the preferred content and timing of cost discussions. Only 3 of the 42 parents (7%) reported ever having discussed their child’s health care costs with an inpatient HCP.

Domain 1: Factors Influencing Parent Desire for Cost Discussions

We identified 4 key factors that influence a parent’s desire to discuss their child’s health care costs in the inpatient setting: (1) responsibility for out-of-pocket expenses, (2) understanding the child’s insurance coverage, (3) parent response to

financial stress, and (4) perceived acuity of their child’s health condition during the hospitalization (Table 2).

Parents who had no out-of-pocket expenses because of their primary insurance coverage orfinancial assistance from the hospital’s

uncompensated care fund seemed less interested in having cost discussions. Although many parents understood their insurance coverage, those who were less familiar expressed a higher desire for cost discussions. These parents felt the lack of transparency of costs left them unprepared to manage their future bills. Parents identified issues such as not knowing when to expect bills, not understanding how to navigate the billing system, and

wanting to have cost discussions before discharge to understand their futurefinancial responsibilities and managefinancial stress.

Many parents desired having greater insight into the overall cost of a hospitalization. Whereas some parents felt that knowing the dollar amount of each procedure or test would be stressful, others felt that having that information would allow them to prepare for future out-of-pocket costs. In addition, a parent’s interest in discussing cost may shift over the course of hospitalization depending on the acuity of their child. Overall, many parents preferred to avoid having cost discussions while their child was in critical condition, on life-sustaining support, or in situations involving end-of-life care. Instead, they preferred having them once their child was medically stable.

Lastly, although parents identified particular factors influencing their desire for cost discussions, parents overwhelmingly felt that the focus of their child’s hospitalization should be

first and foremost their child’s medical care.“It doesn’t feel right for my doctor [to be] worrying about how much things cost and how I’m going to pay my bill. I want them worrying about how to take care of my kid.”

Domain 2: Parent Preferences for the Implementation of Cost Discussions

Parents provided specific recommendations for how they would like cost discussions to be executed, which we divided into who, what, when, where, and how. Categories and quotations illustrating key concepts are provided in Table 3.

Who: Physicians Should Serve as Liaisons for Cost Discussions and Allow Nonphysician Staff Members To Conduct Actual Cost Discussions

Parents expressed strong feelings regarding the role of their physician

FIGURE 1

in cost discussions. Physicians were considered to be individuals directing medical decisions and ordering treatments or therapies as opposed to other HCPs such as nurses, case managers, or social workers. Although many understood that medical decisions made by physicians ultimately lead to increased health care costs, many noted that communication regarding out-of-pocket expenses could negatively impact the therapeutic relationship. Given a physician’s other

responsibilities, parents did not expect physicians to know the cost of a medicine or a patient’s individual insurance details. In addition, many expressed concerns that it may seem as if their physician was more focused on a family’s ability to pay rather than

their child’s condition. Frequently, parents were worried that talking about costs could ultimately lead a physician to make medical decisions (such as discharging a patient prematurely) on the basis of a family’s ability to pay, which they feared may lead to poorer outcomes for their child.“I’d hate for a parent to opt out of a reasonably priced test because they got scared off after having a cost discussion with their doctor, even though it was the right thing to do.”

Some parents expressed a belief that physicians never order unnecessary tests. Consequently, parents felt that cost discussions with their physicians would not impact their decisions because they felt that physicians

“don’t do extra tests just to do them.” One parent expressed,“Because we have a medically complex kid, things aren’t done that don’t need to be done.”

Given these concerns, parents overwhelmingly felt that physicians should serve as liaisons of cost discussions and allow nonphysician staff members to conduct the actual cost discussions (preferably a social worker or afinancial counselor with expertise in insurance and billing matters).“I like that idea of afinancial counselor or social worker if you have billing question, just to get you used to this idea about costs.”Many felt physicians should introduce the option of having a cost discussion with TABLE 2Illustrative Quotations of Factors Influencing Parents’Desirability for Cost Discussions in the Inpatient Setting

Reasons Related to Low Desirability for Cost Discussions Influential Factor Reasons Related to High Desirability for Cost Discussions

No out-of-pocket expenses Responsibility for out-of-pocket

expenses

Moderate-to-large out-of-pocket expenses

“I’m generally of the opinion that cost information should be transparent, but I personally don’t need the level of transparency because my health insurance is good. So, I don’t stress about it. I think that if I knew that I was gonna have to pay a part of it, I would have wanted to be more involved.”B.20

“If it was at the beginning of the year and we hadn’t met our deductible, I would want to know the options, like how much is it going to cost us. What is this going to look like? I would’ve wanted someone to ask‘Do you want to talk about it? And if so, here’s your billing people and we can have that conversation.’”A.9

More familiar with health insurance coverage Understanding the child’s insurance coverage

Less familiar with health insurance coverage

“I knew what my insurance was going to cover. We were okay to know that whatever happened, happened. We were going to do his surgical repair regardless.”A.16

“It would be very nice to know this is how much you should expect to pay so that you can at least know that there’s another thousand dollar bill coming…‘Cause if you’re not savvy to medical, you don’t know that your ambulance is completely separate, and you’re going to get that at another time.”B.7

Hearing about costs increases stress Parent response tofinancial stress Anticipating out-of-pocket expenses relieves stress “I don’t understand the point of the conversation if

we’ve been there a week and then we talk about cost? Is the point just to make you aware of how much money you’re running up on the tab that you probably are not able to pay? That’s overly stressful when you’re stuck in a hospital and you can’t leave. I wouldn’t want to hear it if I was inpatient, let’s just say that.”A.6

“I think when you’re dealing with pediatric care you’re really considering the whole family, and so that’s something that really affects the whole family. So, I feel like it’s really important to have an idea of how much things cost. It’s not just about the medical condition that my son has but the whole family unit and life and structure and how decisions made about his care will affect our quality of life.”B.8 Child is in a medically high acuity state Perceived acuity of their child’s health

condition

Child is in a medically stable state

“If my child is in critical condition, in the ICU, I think it would be really hard for me to navigate a conversation about money when my kid might die.”A.8

“I know that we live in a world with insurance and so many different things, and so I understand that those discussions need to happen. Like when things are stable during the hospitalization, that’s when I would want it to be discussed.”A.11

someone from the billing department if a parent was interested.

What: Cost Discussions Should Include Out-of-Pocket Costs, Prices of High-Cost Procedures, and a Review of Insurance Coverage

Some of the parents expressed frustration around the lack of transparency of the cost of services and, in particular, their own out-of-pocket expenses. Almost all parents preferred discussing out-of-pocket costs as opposed to direct hospital costs, although a few parents were interested in hearing about direct costs purely out of curiosity. Some parents felt discussing out-of-pocket costs might inform futurefinancial decisions. Parents wanted to discuss expensive items and procedures such as MRIs or computed tomography scans, outpatient medications, and daily bed charges. We noted some differences in the preferred content of these discussions between the 2 groups of parents we interviewed. Parents of children without chronic conditions preferred detailed discussions about all aspects of their insurance

coverage such as out-of-pocket maximums and deductibles, whereas parents of children with chronic conditions articulated a desire for a

“refresher course”on specific aspects of their insurance coverage, especially if there had been recent changes to their insurance coverage.

When: Cost Discussions Should Only Take Place When a Child Is in a Stable Medical State

Preferences regarding the optimal timing of cost discussions varied between the 2 groups. Parents of children without chronic conditions preferred the option of engaging in cost discussions within thefirst 2 days, whereas parents of children with chronic conditions articulated that thefirst few days were too chaotic and would prefer to discuss costs after an established plan of care. Many parents wanted the ability to dictate the timing of cost discussions because “the difficulty is that everyone’s perception of when is the right time is different. So take it case by case.”

Where: Cost Discussions Should Occur Bedside With Supplemental Written Resources

Most parents wanted an opportunity to have an in-person discussion at the bedside as well as receive written handouts regarding costs. Several parents described frustrating experiences with calling their insurance provider directly:“I don’t know if telling a parent to

‘contact your insurance provider to

find out what your insurance covers’ is that helpful because you’re exhausted.”

Parents mentioned that an in-person discussion allows for clarifying questions. Parents suggested developing written handouts with estimates of out-of-pocket expenses and a Web site or a phone

application with information on potential out-of-pocket costs. Parents felt that written handouts would be beneficial for those who were not ready to engage in a cost discussion at that moment.“I think that an ideal situation would be,

‘here’s a place you can look at the cost of everything.’I think it would TABLE 3Illustrative Quotations of Parent Preferences for Discussing Health Care Costs in the Inpatient Setting

Category Illustrative Quotations

Who “As a parent, you don’t want to ever have the thought that there is a back-pocket benefit for the doctor to be pushing a certain med. You don’t want to ever have that feeling like‘Oh, well, if you keep pushing this one, are you getting a kickback?’”A.1

“I don’t think doctors should be required to know costs off the top of their head. They should at least be able to truthfully say,‘I don’t know. But I can send you to these people who know, and they will be able to help you.’”B.5

What “It’d be nice if physicians could help understand our future cost. Not the cost of the procedure itself necessarily but what it’s going to cost us

financially, out of our pocket.”A.3

“They talked about giving her vitamin D drops. We said yes, but then I was thinking,‘Well it wasn’t critical, how much are we paying for these drops? Is that going to be $500 for a vitamin drop that I can go to our pharmacy and get for $20 that’ll last us a month?’So if something like a medicine was being offered, that might be a good time to say,‘If you decide this, this is how much this would cost you.’”B.20 When “You don’t want to wait too long to bring it up if parents want to talk about it. But you also don’t want to hit them the next morning at 7AMwhen

theyfinally get to bed at 3AM. If it’s feasible at the end of the second full day, I think that would be okay.”A.10

“I think as early on as possible. I think that should be the goal, so in case learning something about insurance impacts a decision for care or a parent’s decisions along the way.”B.6

Where “I personally would need that to be talked through and then given some sort of paper copy. When I am stressed out and things are going nutso, my ability to read and comprehend is restricted. If I had somebody sitting there with a document and a pen where I could take a note and highlight different things and hear it, then my auditory works better than my visual when I’m stressed.”A.9

“I think there’s value in having the conversation because it allows people to ask questions. But I think it also needs to be written down because, when you’re a parent, you’re tired and you’re dealing with a sick child; you’re listening, but you’re also distracted. If you go to sit down later, you’re like,‘Oh God, what did they tell me? I just have no clue!’”B.1

How “You don’t know what stressors they have. I think there are some families where the money is the stressor and they absolutely need to talk about that and there’s other families where the stressors are other places and they don’t need one more straw.”A.9

“Everyone comes from a differentfinancial and emotional background, and a lot of docs just haven’t had that experience of having their own child in the hospital.”B.16

be nice if parents have concerns to know there’s a place they can go where everything is listed in one place.”

How: Cost Discussions Should Be Optional With an Individualized Approach

Parents felt that cost discussions should be both optional and tailored to each family’s unique needs and preferences because each family has their own“comfort level with their ownfinancial situation.”

Overwhelmingly, parents felt that cost discussions should be made available but not required.“Each family likes to handle theirfinances in a different way. Maybe give the family the option of talking to someone in billing at any point during their stay.”They noted that a nurse or physician should offer the option early in a hospitalization to alert parents of the opportunity but without pressure to have the discussion. They also preferred to receive instructions on how to contact someone in case they wanted to have discussions later in their child’s hospitalization. A few parents expressed embarrassment toward theirfinancial struggles, which made cost discussions undesirable.

Parents also suggested language that HCPs could use to introduce cost discussions in a sensitive, nonjudgmental manner, using opening statements that maintain trust while legitimizing and

normalizing a family’s possible

financial concerns. Examples of scripts for HCPs are included in Table 4.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we examined parent preferences for discussing their child’s health care costs in the inpatient setting. Parents in our study reported that cost discussions were rare, and the desirability of cost discussions varied on the basis of their unique values and preferences. They felt these discussions should be optional and should ideally occur with a financial counselor or social worker rather than a physician. Parents suggested the content of these discussions should primarily consist of reviewing their expected out-of-pocket costs. Parents of children with and without chronic conditions shared similar

preferences except for their recommendations regarding the preferred content and timing of cost discussions.

Results of our study support previous research that suggests patient-HCP communication about health care costs occurs infrequently. However, unlike previous studies, participants in this study prefer that physicians serve as facilitators who connect parents to other resources for more in-depth discussions around cost. This is consistent with recently published online

cost-of-care modules suggesting that physicians should attempt to screen all families for their desire to discuss health care costs.21

Parents expressed dissatisfaction around the lack of transparency for the cost of services and out-of-pocket expenses. Currently, there are few pediatric-specific cost Web sites, and most provide estimates rather than individualized information.22,23 In this study, participants suggested a combination of in-person cost discussions as well as easy-to-access individualized cost information, either in writing or online. One potential practical application of this could include providing parents with a hospital-specific orientation packet on admission. Included in these materials could be information that alerts families tofinancial resources and experts who can provide patient-specific insurance and cost

information. Hospitals should also ensure that staff members with expertise in billing are easily accessible to families.

In this study, we identified important factors explaining the absence of cost discussions at children’s hospitals. Some parents were afraid that their child would receive suboptimal care; for example, their child’s physician might avoid obtaining a necessary test because of the physician’s perception that a family could not pay or rush to discharge a child before they were medically ready.

TABLE 4Examples of HCP Scripts That Can Be Used To Introduce Cost Discussions With Parents

Illustrative Quotations Parent

“When you’re getting closer to discharge, would you like someone from ourfinancial department to come and talk to you?” B.14 “We want you to focus on your child and not worry about thefinances. We want every kid to have a roof over their head when they leave here.” A.8

“I tell everyone this. I’m not just singling you out because you can or can’t afford it.” B.8

“We’re looking at really high costs because of the nature of the care that your child needs. So, we want to make sure that we’re doing all we can to both mitigate and give you the opportunity to be as informed as possible about what you might be facing and what resources are out there for you.”

A.22

“It would be great if they could help us get a better understanding of our insurance coverage so that they can tell us‘This is how much you will have to pay at the end.’Again, I don’t think physicians have time to do that; it’s probably somebody else that’s running those numbers and compiling all of that information for us.”

B.10

“If you have any questions about any of the billing on all this, we can have someone come talk with you. That’s not my job, but if you have concerns, let me know and I can have someone talk to you.”

B.15

This fear of cost conversations resulting in harm is in contrast to adult studies in which adults more openly want to have cost discussions with their HCPs. When serving as a proxy in medical decisions for another person, people experience different emotional responses regarding the prospect of causing harm to another versus

themselves.15In addition, responsibility may make people analyze decisions differently, such as minimizing the importance of cost implications and placing more weight on other components of the decision.24,25

Although parents were concerned that cost conversations may result in their child receiving inappropriate care, parents repeatedly expressed a high degree of trust that their physicians did not provide unnecessary care. Although

researchers indicate that physicians frequently order unnecessary tests,26,27parents’awareness may be limited because of the fact that value-based discussions rarely occur at the bedside with families.28,29 Although parents in our study generally did not want physicians to conduct discussions about cost, physicians can still help support a patient’s understanding of health care value. Physicians can engage in open and transparent discussions about which diagnostic tests are truly necessary, what the potential benefits are to their child, and what downstream harms can occur from overuse. This level of discussion can help better prepare families when they engage in discussions about cost withfinancial counselors. Engaging parents in value-based discussions in this way may ultimately allow for the integration of costs into the shared decision-making process in the future.

Participants in our study suggested HCPs should consider using language to introduce cost discussions that

parallel HCP scripts for obtaining other sensitive pieces of history, such as a sexual history (Table 4). Using normalizing language is consistent with other published work that aims to diminish embarrassment when initiating potentially sensitive discussions.30Faculty development programs and trainee workshops could incorporate these scripts to promote best practices for eliciting parent interest in having cost discussions.

Despite the desire of our participants for cost discussions to not be led by physicians, there may be times when physician involvement is necessary.31,32For example, physicians may need to discuss whether to order a test in the inpatient setting versus the

outpatient setting or whether to use a generic versus a brand-name medication, or, when cost concerns are raised, physicians may need to provide reassurance that the patient is receiving the appropriate level of care. Therefore, although physicians may primarily serve in a triage role, physicians will likely be called on to engage in discussions about costs and should be prepared to have these discussions.

We recognize this study has limitations. First, there is potential for response bias among our participants, particularly among the parents from our family advisory council. Participants from this group represent a voluntary, self-selected group of parents who may have been more adept in navigating the health care system, and thus their

perspectives may be atypical. Although generalizability to wider populations may be limited, we attempted to minimize this limitation by including parents of children without chronic conditions who are likely to have different perspectives and preferences around cost discussions, as our study revealed. Given that discussion

aroundfinances can be impacted by cultural differences, we acknowledge that only including English-speaking families is another limitation. Next, we interviewed most parents before they received their child’s hospital bill. Their perspectives may have differed had we interviewed them after they had received the bill. Lastly, our hospital has a robust uncompensated care fund that may affect some of the participants because a majority of their care is fully covered. Children who are hospitalized at nontertiary care sites and community settings without robust care funds may have differing views. Future studies are needed to elucidate whether thesefindings are generalizable in other settings and populations, potentially with administration of a survey that incorporates our studyfindings.

CONCLUSIONS

Parents of children who are hospitalized want to engage in cost discussions. However, these

discussions should be tailored to the needs and preferences of each family. Because of a concern that cost discussions may negatively impact the care of their child, families preferred that physicians introduce rather than conduct these

discussions. Our studyfindings may be used by HCPs and hospital administrators to initiate and improve on cost discussions with families during inpatient encounters.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Dr Christopher Moriartes for his thoughtful review of this article.

ABBREVIATION

Address correspondence to Jimmy Beck, MD, MEd, Department of Pediatrics, Seattle Children’s Hospital, 4800 Sandpoint Way NE, M/S FA.2.115, Seattle, WA 98105. E-mail: jimmy.beck@seattlechildrens.org

PEDIATRICS (ISSN Numbers: Print, 0031-4005; Online, 1098-4275).

Copyright © 2019 by the American Academy of Pediatrics

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE:The authors have indicated they have nofinancial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

FUNDING:Supported by the 2017 Beryl Institute’s Patient Experience grant, Seattle Children’s Center for Clinical and Translational Research Faculty Research Support Fund, and the Institute of Translational Health Science Early Investigator Catalyst Award at the University of Washington. Dr Desai was supported by grant

K08HS024299 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. These funding sources have no involvement in the study design, data collection, analysis, writing of the article, or decision to submit for publication.

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST:The authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

1. Schoen C, Collins SR, Kriss JL, Doty MM. How many are underinsured? Trends among U.S. adults, 2003 and 2007.

Health Aff (Millwood). 2008;27(4):

w298–w309

2. Himmelstein DU, Thorne D, Warren E, Woolhandler S. Medical bankruptcy in the United States, 2007: results of a national study.Am J Med. 2009;122(8): 741–746

3. Moriates C, Shah NT, Arora VM. First, do no (financial) harm.JAMA. 2013;310(6): 577–578

4. Hunter WG, Ubel PA. The black box of out-of-pocket cost communication. A path toward illumination.Ann Am

Thorac Soc. 2014;11(10):1608–1609

5. Meisenberg BR, Varner A, Ellis E, et al. Patient attitudes regarding the cost of illness in cancer care.Oncologist. 2015; 20(10):1199–1204

6. Bullock AJ, Hofstatter EW, Yushak ML, Buss MK. Understanding patients’ attitudes toward communication about the cost of cancer care.J Oncol Pract. 2012;8(4):e50–e58

7. Kelly RJ, Forde PM, Elnahal SM, Forastiere AA, Rosner GL, Smith TJ. Patients and physicians can discuss costs of cancer treatment in the clinic.

J Oncol Pract. 2015;11(4):308–312

8. Alexander GC, Casalino LP, Tseng CW, McFadden D, Meltzer DO. Barriers to patient-physician communication about out-of-pocket costs.J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(8):856–860

9. Bestvina CM, Zullig LL, Rushing C, et al. Patient-oncologist cost communication, financial distress, and medication

adherence.J Oncol Pract. 2014;10(3): 162–167

10. Irwin B, Kimmick G, Altomare I, et al. Patient experience and attitudes toward addressing the cost of breast cancer care.Oncologist. 2014;19(11): 1135–1140

11. Galbraith AA, Sinaiko AD, Soumerai SB, Ross-Degnan D, Dutta-Linn MM, Lieu TA. Some families who purchased health coverage through the Massachusetts Connector wound up with highfinancial burdens.Health Aff (Millwood). 2013; 32(5):974–983

12. Bui AL, Dieleman JL, Hamavid H, et al. Spending on children’s personal health care in the United States, 1996-2013.

JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171(2):181–

189

13. Cohen E, Friedman J, Nicholas DB, Adams S, Rosenbaum P. A home for medically complex children: the role of hospital programs.J Healthc Qual. 2008;30(3):7–15

14. Berry JG, Hall M, Neff J, et al. Children with medical complexity and Medicaid: spending and cost savings.Health Aff

(Millwood). 2014;33(12):2199–

2206

15. Zikmund-Fisher BJ, Sarr B, Fagerlin A, Ubel PA. A matter of perspective: choosing for others differs from choosing for yourself in making treatment decisions.J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(6):618–622

16. Committee on Hospital Care and Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care. Patient- and family-centered care and the pediatrician’s

role.Pediatrics. 2012;129(2):394– 404

17. Sofaer S. Qualitative methods: what are they and why use them?Health Serv Res. 1999;34(5 pt 2):1101–1118

18. Hunter WG, Hesson A, Davis JK, et al. Patient-physician discussions about costs: definitions and impact on cost conversation incidence estimates.BMC

Health Serv Res. 2016;16:108

19. Angen MJ. Evaluating interpretive inquiry: reviewing the validity debate and opening the dialogue.Qual Health Res. 2000;10(3):378–395

20. Guest G, MacQueen KM, Namey EE.

Applied Thematic Analysis. Thousand

Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications; 2012:3–20

21. Costs of Care. Value conversations modules. 2017. Available at: http:// costsofcare.org/value-conversations-modules/. Accessed August 14, 2018

22. Faherty LJ, Wong CA, Feingold J, et al. Pediatric price transparency: still opaque with opportunities for improvement.Hosp Pediatr. 2017;7(10): 565–571

23. Racimo AR, Talathi NS, Zelenski NA, Wells L, Shah AS. How much will my child’s operation cost? Availability of consumer prices from US hospitals for a common pediatric orthopaedic surgical procedure.J Pediatr Orthop. 2018;38(7):e411–e416

24. Jonas E, Schulz-Hardt S, Frey D. Giving advice or making decisions in someone else’s place: the influence of

25. Kray L, Gonzalez R. Differential weighting in choice versus advice: I’ll do this, you do that.J Behav Decis Mak. 1999;12(3):207–218

26. Sedrak MS, Patel MS, Ziemba JB, et al. Residents’self-report on why they order perceived unnecessary inpatient laboratory tests.J Hosp Med. 2016; 11(12):869–872

27. Koch C, Roberts K, Petruccelli C, Morgan DJ. The frequency of unnecessary testing in hospitalized patients.Am

J Med. 2018;131(5):500–503

28. Beck JB, McDaniel CE, Bradford MC, et al. Prospective observational study on high-value care topics discussed on multidisciplinary rounds.Hosp Pediatr. 2018;8(3):119–126

29. Patel MS, Reed DA, Smith C, Arora VM. Role-modeling cost-conscious care–a national evaluation of perceptions of faculty at teaching hospitals in the united states.J Gen Intern Med. 2015; 30(9):1294–1298

30. Piette JD, Heisler M, Wagner TH. Cost-related medication underuse: do

patients with chronic illnesses tell their doctors?Arch Intern Med. 2004;164(16): 1749–1755

31. Henrikson NB, Shankaran V. Improving price transparency in cancer care.J Oncol Pract. 2016;12(1):44– 47

32. Hunter WG, Zafar SY, Hesson A, et al. Discussing health care expenses in the oncology clinic: analysis of cost conversations in outpatient encounters.

J Oncol Pract. 2017;13(11):e944–

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2018-4029 originally published online July 3, 2019;

2019;144;

Pediatrics

Nora B. Henrikson and Arti D. Desai

Jimmy Beck, Julia Wignall, Elizabeth Jacob-Files, Michael J. Tchou, Alan Schroeder,

Inpatient Setting

Parent Attitudes and Preferences for Discussing Health Care Costs in the

Services

Updated Information &

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/144/2/e20184029 including high resolution figures, can be found at:

References

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/144/2/e20184029#BIBL This article cites 30 articles, 12 of which you can access for free at:

Subspecialty Collections

ent_safety:public_education_sub

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/patient_education:pati Patient Education/Patient Safety/Public Education

b

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/hospital_medicine_su Hospital Medicine

following collection(s):

This article, along with others on similar topics, appears in the

Permissions & Licensing

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/Permissions.xhtml in its entirety can be found online at:

Information about reproducing this article in parts (figures, tables) or

Reprints

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2018-4029 originally published online July 3, 2019;

2019;144;

Pediatrics

Nora B. Henrikson and Arti D. Desai

Jimmy Beck, Julia Wignall, Elizabeth Jacob-Files, Michael J. Tchou, Alan Schroeder,

Inpatient Setting

Parent Attitudes and Preferences for Discussing Health Care Costs in the

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/144/2/e20184029

located on the World Wide Web at:

The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/suppl/2019/06/20/peds.2018-4029.DCSupplemental Data Supplement at:

by the American Academy of Pediatrics. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 1073-0397.