INSTABILITY AND ITS EFFECTS ON THE FAMILY LIVELIHOODS IN MACHAKOS COUNTY, KENYA.

MUSAU JACKSON MASUA BE’D (Arts), MA (Population Geography)

REG.NO.C82/22574/2011

A THESIS SUBMITTED IN FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (POPULATION GEOGRAPHY) IN THE SCHOOL OF HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES

OF KENYATTA UNIVERSITY

DECLARATION

This thesis is my original work and has never been presented for a degree in any other university

Signature ……….. Date……….. JACKSON MASUA MUSAU

DEPARTMENT OF GEOGRAPHY KENYATTA UNIVERSITY

DECLARATION BY SUPERVISORS

This thesis has been submitted for review with our approval as University supervisors

Signature……… Date……….. PROF.LEONARD M. KISOVI

DEPARTMENT OF GEOGRAPHY KENYATTA UNIVERSITY

Signature………. Date……… DR.SAMUEL C.J OTOR

DEDICATION

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

TABLE OF CONTENTS

DECLARATION... ii

DEDICATION... iii

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ... iv

TABLE OF CONTENTS ... v

LIST OF TABLES ... xii

LIST OF FIGURES ... xv

LIST OF BOXES ... xvii

ABREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ... xviii

ABSTRACT ... xx

CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION ... 1

1.1 Overview ... 1

1.2 Background to the Study ... 1

1.3 Statement of the Problem ... 7

1.4 Research Questions ... 8

1.5 Objectives of the Study ... 9

1.6 Hypotheses of the Study ... 9

1.7 Justification of the Study ... 10

1.8 Scope and Limitations... 13

1.9 Operational Definitions of Key Terms ... 15

1.10 Ethical Consideration ... 21

1.11 Summary ... 21

CHAPTER TWO: LITERATURE REVIEW ... 22

2.1 Introduction ... 22

2.2 Empirical Studies ... 22

2.2.1 Demographic Factors ... 23

2.2.1.1 Age at First Marriage ... 23

2.2.1.3 Age of Children...27

2.2.1.4 Premarital/Marital Birth ...27

2.2.1.5Remarriage ...28

2.2.2 Spatial-Temporal Factors ... 29

2.2.2.1 Marriage Duration ... 29

2.2.2.2 Living Arrangements ... 29

2.2.2.3 Premarital Cohabitation ...30

2.2.3 Family Background ... 32

2.2.3.1 Parents Socio-Economic Status ...33

2.2.3.2 Parental Separation ... 35

2.2.4 Respondent’s Socio-Economic Factors ... 36

2.2.4.1 Education ...37

2.2.4.2 Economic Circumstances ...38

2.2.4.3 Women’s Employment in Paid Work ...40

2.2.4.4 Religiosity ...41

2.2.4.5 Previous Experience of Partnership Dissolution ...41

2.2.5 Attitudes to Divorce ... 42

2.3 Marital Instability Levels Worldwide ... 43

2.4 Divorce Levels in Africa ... 50

2.5 Theoretical Framework ... 61

2.5.1 Introduction ... 61

2.5.2 Economic theory ... 61

2.5.3 Social Exchange Theory ... 65

2.5.4 Behavioural Theory ... 67

2.5.5 Crisis Theory ... 69

2.5.6 Vulnerability-Stress-Adaptation Model ... 70

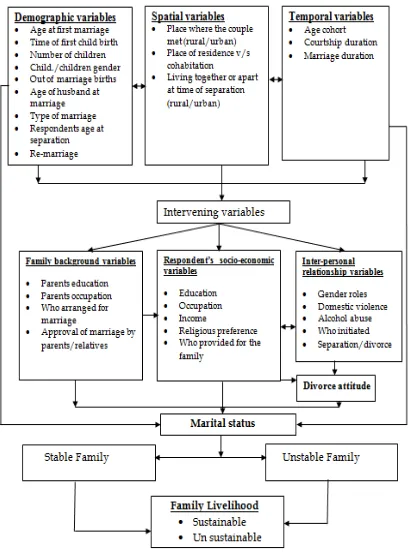

2.6 Conceptual Framework ... 72

CHAPTER THREE: RESEARCH METHODOLOGY ... 76

3.1 Introduction ... 76

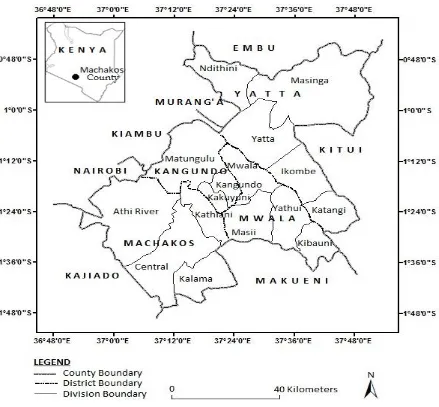

3.2 Study Area ... 76

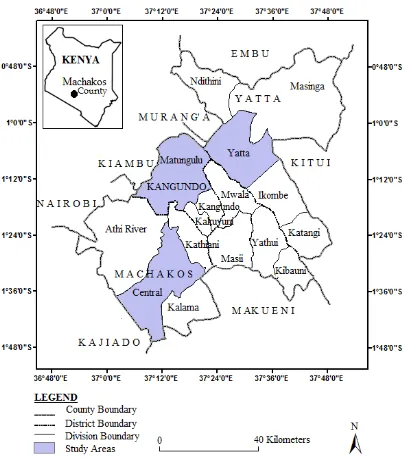

3.3 Research Design and Sampling Techniques ...80

3.3.1 Research Design...80

3.3.2 Sampling Techniques ... 80

3.4 Data Types ... 86

3.4.1 Primary Data ... 86

3.4.2 Secondary Data ... 86

3.5 Data Collection Methods ... 86

3.5.1 Qualitative Data Collection Methods... 87

3.5.1.1 Focus Group Discussions (FGD’S) ... 87

3.5.1.2 Key Informant Interview... 88

3.5.2 Quantitative Data Collection Method ... 89

3.6 Data Collection Instruments ... 89

3.7 Variables ... 90

3.7.1 Dependent Variables ... 90

3.7.2 Independent Variables ... 90

3.8 Training of Research Assistants... 92

3.9 Pilot Study ... 92

3.10 Reliability of the Collected Data ... 95

3.11 Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria ... 95

3.12 Data Analysis ... 95

3.12.1 Chi-square Test (χ2) ... 96

3.12.2 Pearson’s Product Moment Correlation Coefficient( r ) ... 97

3.12.3 Logistic Regression Analysis ... 98

CHAPTER FOUR: RESULTS OF THE DEMOGRAPHIC AND

SPATIAL-TEMPORAL FACTORS ... 101

4.1 Introduction ... 101

4.1.1 Respondents Age at First Marriage... 101

4.1.2 Age of Husband at Marriage ... 107

4.1.3 Type of Marriage ... 109

4.1.4 Time at First Child Birth ... 111

4.1.5 Number of Children (Fertility)... 112

4.1.6 Child/Children Gender ... 115

4.1.7 Non-Marital Births ... 116

4.1.8 Respondents Age at Separation ... 118

4.2 Spatial Variables ... 121

4.2.1 Place Where the Couple Met ... 121

4.2.2 Cohabitation and Place of Residence Before Marriage ... 123

4.2.2.1 Factors Associated with Cohabitation Before Marriage ... 126

4.2.3 Living Together or Apart Before Separation ... 128

4.3 Temporal Variables ... 130

4.3.1: Courtship Duration ... 130

4.3.2 Duration of Marriage ... 133

4.4 Summary ... 137

CHAPTER FIVE: RESPONDENT’S FAMILY BACKGROUND, SOCIO-ECONOMIC AND INTERPERSONAL RELATIONSHIP CHARACTERISTICS 139 5.1 Introduction ... 139

5.2 Family Background ... 140

5.2.1 Parents Education ... 140

5.2.2 Parents’ Occupation ... 142

5.2.3 Decision for Marriage ... 143

5.2.4 Approval of Marriage by Parents/Relatives ... 144

5.3 Respondents’ Socio-Economic Characteristics ... 150

5.3.1 Respondents’ Education Level ... 150

5.3.2 Spouses’ Occupation at the Time of Marriage ... 153

5.3.3 Household Income ... 157

5.3.4 Wife/Husband Religious Preference ... 159

5.4 Interpersonal Relationship Variables ... 162

5.4.1 Gender Roles ... 162

5.4.2 Effects of Domestic Violence on Marital Instability ... 164

5.4.2.1 Sexual Assaults ... 165

5.4.2.2 Physical Assault ... 166

5.4.2.3 Emotional Abuse ... 170

5.4.3 Alcohol and Drug Use ... 171

5.5 Challenges Faced by Women in Addressing Domestic Violence ... 172

5.6 Decision for Separation/ Who Initiated Separation ... 174

5.7 Divorce Attitude... 177

5.8 Summary ... 181

CHAPTER SIX: RESULTS ON THE NATURE OF MARITAL STATUS AND ITS EFFECTS ON THE FAMILY LIVELIHOODS ... 182

6.1 Introduction ... 182

6.2 Nature of Marital Status ... 182

6.3 Remarriage ... 184

6.4 Parents Marital Status ... 187

6.5 Reported Major Reasons for Marital Instability ... 188

6.6 Effects of Marital Instability on the Family Livelihoods... 197

6.6.1 Husbands/Wives Occupation at Separation and After Separation ... 198

6.6.2 Other Sources of Income for Separated Women ... 202

6.6.3 Association Between Marital Status and Respondents livelihood options ... 203

6.6.4 Socio-economic Changes/ Challenges Faced by Separated Women ... 205

6.6.4.1 Respondent Place of Residence After Separation ... 208

6.6.4.3 Children Age at Separation ... 211

6.6.3.4 Children level of Education ... 212

6.6.3.5 Perceptions on the Quality of Life After Marriage Dissolution ... 217

CHAPTER SEVEN: SUMMARY, CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS ... 220

7.1 Summary ... 220

7.2 Conclusion ... 227

7.3 Recommendations ... 228

7.4 Avenues for Further Research ... 234

REFERENCES ... 236

APPENDICES ... 253

Appendix 1: Research Instrument (Questionnaire)... 253

Appendix 2: Focus Group Discussion/Key informants Interview Guide ... 265

Appendix 3: Percentage Distributions of Household Heads by Marital Status and Counties. ... 266

Appendix 4: Distribution of Household Headship by Gender and Poverty Status ... 267

Appendix 5: Cross Tabulation Result of Demographic Variables by Age Cohort ... 268

Appendix 6: Cross Tabulation Result of Spatial-Temporal Variables by Age Cohort ... 270

Appendix 7: Cross Tabulation Result of Family Background Variables and Age Cohort ... 271

Appendix 8: Cross tabulation Result of Respondents Socio-economic Variables Across the Age Cohort ... 272

Appendix 9: Cross Tabulation Result of Interpersonal Variables and Age Cohorts ... 273

Appendix 10: Cross Tabulation Result of the Nature of Marital Status Across the Age Cohort ... 275

Appendix 11: Cross Tabulation Result of Effects of Marital Instability Across the Age Cohort ... 276

Appendix 13: Cross Tabulation Results of Respondents Education & Parents Education Level. ... 283 Appendix 14: Cross Tabulation Results of Respondents Education & Parents Occupation. ... 284 Appendix 15: Cross Tabulation Results of Cohabitation & Place of Residence. ... 285 Appendix 16: Cross Tabulation Results of Marital Instability & Interpersonal

Relationship Variables. ... 286 Appendix 17: Chi-square Results on the Relationship Between the Number of Children,

their Age, Gender & Marital Instability. ... 287 Appendix 18: Cross Tabulation Result of the Number of School Going and Non-School

LIST OF TABLES

Table 2.1: General Divorce Rates (Number of Divorce per 1000 Population Aged 15+), in

Various Countries and Regions, 1980-2005. ... 46

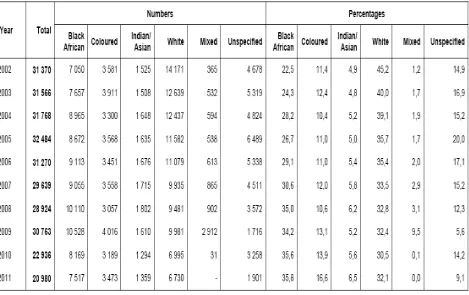

Table 2.2: Number of Published Divorces in South Africa by Population Group, 2002-2011 ... 52

Table 2.3: Percentage Distribution of Women and Men Aged 15-49 by Current Marital Status; 2008/09 in Kenya ... 54

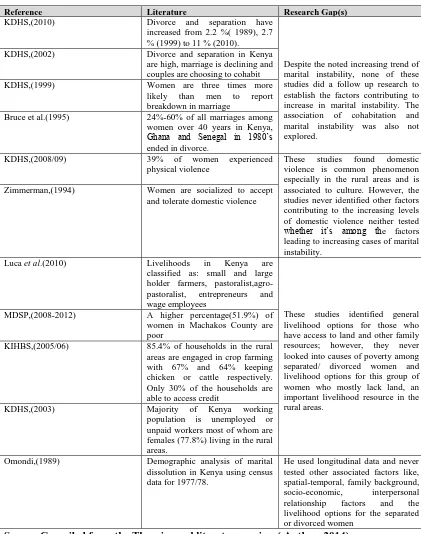

Table 2.4: Summary of Literature Review and Identified Research Gaps ... 60

Table 3.1: Population size, Number of Households, Area, Density and Districts in Machakos County ... 77

Table 3.2: Sampling Procedure for the Respondents in the Area of Study ... 83

Table 3.3: Number of Respodents per District by Age Cohorts ... 85

Table 3.4: The Independent Variables of the Study ... 91

Table 3.5: Number of Respondents’ who Responded During Pilot Study ... 93

Table 3.6: A Summary of Study Objectives, Data Collected and Methods of Data Analysis. ... 99

Table 4.1: Respondents Age at First Marriage Across the Age Cohorts. ... 103

Table 4.2 : Couples Age at First Marriage ... 104

Table 4.3: Factors Influencing Age at First Marriage ... 104

Table 4.4: Association Between Various Variables and Age at First Marriage ... 106

Table 4.5: Distribution of Husbands by Age at Marriage ... 107

Table 4.6: Time When the Respondents Got Their First Child. ... 111

Table 4.7: Total Number of Children per Respondent ... 113

Table 4.8: Number of Children from this Marriage ... 114

Table 4.9: Number of Non-Marital Births Before/After Separation... 116

Table 4.10: Number of Sons/ Daughters Before Marriage and After Separation ... 117

Table 4.11: Demographic Variables & their Effects on Marital Instability. ... 119

Table 4.12: Logistic Regression Model on Demographic Variables ... 121

Table 4.13: Place Where the Couple Met ... 122

Table 4.15: Association Between Marital Instability & Spatial Variables; ... 129

Table 4.16: Logistic Regression Model on the Spatial Variables ... 130

Table 4.17: Duration of Marriage Across Age Cohorts ... 134

Table 4.18 : Factors Influencing the Duration of Marriage ... 136

Table 4.19: Association Between Marital Instability and Temporal Variables. ... 136

Table 4.20: Logistic Regression Model on Temporal Variables ... 137

Table 5.1: Parents Level of Education ... 140

Table 5.2: Parents’ Occupation ... 142

Table 5.3: Decision for Marriage ... 143

Table 5.4: Marriage Approved by: ... 144

Table 5.5: Association of Marital Instability & Family Background Variables. ... 148

Table 5.6: Logistic Regression Results of Respondents Family Background Characteristics. ... 149

Table 5.7: Employment Status of the Couple at the Time of Marriage. ... 154

Table 5.8: Spouses’ Occupation Before Marriage ... 154

Table 5.9: Who Provided for the Family ... 158

Table 5.10: The Couples Religious Preference... 160

Table 5.11: Association Between Marital Instability and Respondents Socio-Economic Variables ... 161

Table 5.12: Gender Role Ideas... 163

Table 5.13: Reasons for Sexual Assault ... 165

Table 5.14: Frequency of Sexual Assault ... 166

Table 15: Relationship Between Husbands Threats and Other types of Domestic Violence ... 168

Table 5.16: The level of Physical Assault in the Community ... 168

Table 5.17: Reported Reasons for Physical Assaults Among the Women in the Community ... 169

Table 5.18: Reasons Behind Respondents Fathers Abuse to Their Mothers ... 170

Table 5.19: Reported Sources of Help to Victims of Physical Sexual Assaults ... 172

Table 5.20: Challenges Faced by Women in Addressing Domestic Violence ... 173

Table 5.22: Association of Marital Status with Physical, Sexual and Emotional Assault. 176

Table 5.23: Effects of Overall Domestic Assault on Marital instability. ... 177

Table 5.24: Effects of Individual Domestic Assault on Marital instability ... 177

Table 5.25: Divorce Attitude ... 178

Table 6.1: Distribution of Remarriage Across the Age Cohorts ... 185

Table 6.2: Distribution of Marital Status of the Husbands After Separation ... 186

Table 6.3: Parents Marital Status ... 187

Table 6.4: Distribution of Reported Major Reasons for Marital Instability ... 189

Table 6.5: Reasons for Marital Breakdown of the Respondents Parents ... 191

Table 6.6: Reasons for Relationship Breakdown Before Marriage ... 192

Table 6.7: Factors Influencing Separation and Divorce ... 193

Table 6.8: Association Between Separation/Divorce Trend and the Current Respondent Marital Status. ... 197

Table 6.9: Association Between Livelihood Options & Marital Instability at Separation/ After Separation ... 202

Table 6.10: Distribution of Other Sources of Income for Separated Women ... 203

Table 6.11: Multiple Regression Results on the Effects of Overall livelihood Status on Marital instability ... 204

Table 6.12: Respondents Place of Residence After Separation ... 208

Table 6.13: Children’s Place of Residence After Separation of their Parents ... 210

Table 6.14: Distribution of Respondents Children by Age at Separation ... 211

Table 6.15: Number of Children by Education Attainment per Respondent ... 213

Table 6.16: School Dropout Rates ... 215

LIST OF FIGURES

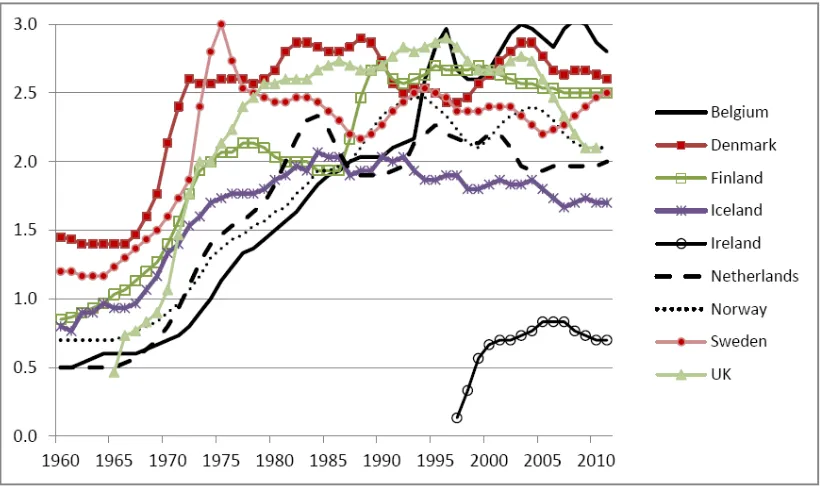

Figure 2.1: Crude Divorce Rates in North Europe Countries, 1960 -2011 ... 48

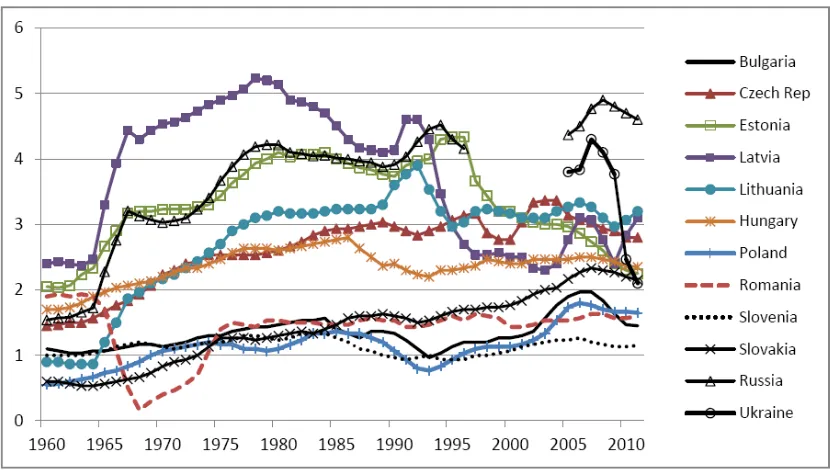

Figure 2.2: Crude Divorce Rates in Central and Southern Europe Countries, 1960 -2011 48 Figure 2.3: Crude Divorce Rates in Eastern Europe Countries, 1960 -2011 ... 49

Figure 2.4: Crude Divorce Rates in Other Industrialized Countries, 1960 -2011 ... 49

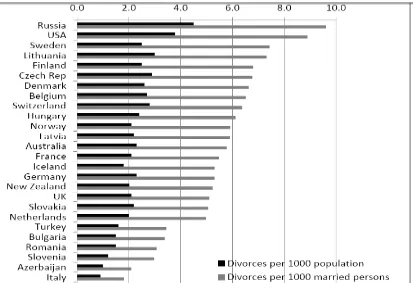

Figure 2.5: Crude Divorce Rate and Divorce per 1000 Married Women in 26 Countries in 2009. ... 50

Figure 2.6: Number of Divorces by Age Group (Males), in South Africa, 2011 ... 53

Figure 2.7: Number of Divorces by Age Group and Population Group, (Females) in South Africa, 2011. ... 53

Figure 2.8: Stress-Vulnerability-Adaptation Model ...71

Figure 2.9 Conceptual Model on the Demographic and Spatial-Temporal Dimensions of Marital Instability in Machakos County ... 74

Figure 3.1: Machakos County Districts/ Divisions. ...78

Figure 3.2: Sampled Divisions in Machakos County. ...84

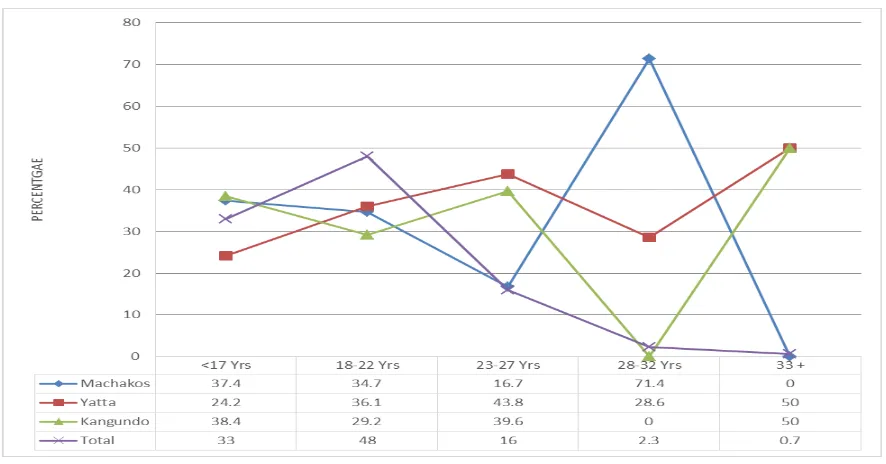

Figure 4.1: Distribution of Respondents in Each District by Age at Marriage ... 104

Figure 4.2: Distribution of Respondents Husband Age at Marriage in Each District. ... 108

Figure 4.3: Distribution of Respondents by the Type of Marriage ... 109

Figure 4.4: Distribution of Respondents by Time at First Child Birth per District ... 112

Figure 4.5: Number of Sons/Daughters from this Marriage ...115

Figure 4.6: Distribution of Non-Marital Births Across the Sampled Districts ... 117

Figure 4.7: Distribution of Respondent by Age at Separation ... 118

Figure 4.8: Lived with a Man Before Marriage ...123

Figure 4.9: Distribution of Respondents by Duration of Cohabitation Across The Sampled Districts ... 125

Figure 4.10: Distribution of Respondent’s by Courtship Duration...131

Figure 4.11: Distribution of Respondents by Courtship Duration, and District ... 133

Figure 4.12: Distribution of Respondents by Marriage Duration, by Sampled Districts .. 135

Figure 5.1: The Level of Education of the Respondent and Her Husband ...151

Figure 5.3: Distribution of Respondents Income Across the Sampled Districts ... 158

Figure 5.4: Distribution of Respondents by who initiated separation/Divorce ... 174

Figure 5.5: Distribution of Respondents Feeling of Re-uniting with Spouse ...180

Figure 6.1: Distributions of Respondents by the Nature of Marital Status. ...183

Figure 6.2: Distributions of Respondents by the Nature of Marital Status Across the Districts. ...184

Figure 6.3: Major Reasons for Separation/ divorce across the Sampled Districts. ... 190

Figure 6.4: Reported Socio-Economic Challenges Faced by Separated Women. ... 205

LIST OF BOXES

Box 4.1: Case Reporting on Courtship Duration ... 132 Box 5.1: Report on the Level of Social Stigma in Machakos County ... 146 Box 5.2: Key Informant Report on Social Stigma by Local Administration Officers ... 146 Box 5.3: Respondents Attitude on Challenges Facing Women in Addressing Domestic Violence ... 173 Box 6.1: Key Informant Report on a Case of Remarriage in Machakos County. ... 186

ABREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS

EU : European Union

CBS : Central Bureau of Statistics

FGD’s : Focus Group Discussions

GO’s : Governmental Organizations

H H : Household Head

KDHS : Kenya Demographic Health Survey

KIHBS : Kenya Integrated Household Budget Survey

KNBS : Kenya National Bureau of Statistics

LDC’s : Less Developed Countries

MDC’s : Most Developed Countries

MDDP : Machakos District Development Plan

MDSP : Machakos District Strategic Plan

MDG’s : Millennium Development Goals

NCST : National Council for Science and Technology

NGO’s : Non-Governmental Organizations

OECD : Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development

SHSS : School of Humanities and Social Sciences

SPSS : Statistical Package for Social Sciences

UN : United Nations

WFS : World Fertility Survey

ABSTRACT

CHAPTER ONE

INTRODUCTION

1.1 Overview

This chapter gives an overview of the background to the study, statement of the research problem, study objectives, research questions, research hypotheses, justification and significance as well as the scope and limitations.

1.2 Background to the Study

Marriage and family life have undergone major changes during the past few decades globally, Kenya included. As a result, in the last two decades, the family has become more dynamic in structure and prone to changes (Haskey, 1997). According to Mbiti (2006) , marriage has been elementary in the foundation of every family. Past studies suggest that, traditionally, marriage was socially necessary as a norm, and for legitimizing sexual relationships and procreation. Most communities, took marriage as a lifelong responsibility (Coltrane, 1996). Women’s role in the family was closely bound up with childbearing/ motherhood which was commonly valued by the family and the society. Inability to procreate was socially looked down upon and a barren woman was restrained by socially imposed norms and often discarded by husband and made to accept co-wives (Kilbride, 1994). Among the Kamba community, the man married a co-wife or allowed the woman to marry another woman (“Iweto”) if she could not give birth for the sole purpose of enhancing procreation and liveage.

(Mbiti,2006).The main purpose of patriarchal system is to enhance/maintain overall subordination of women and dominance of men (Kilbride,1994) .Today, however, marriages are not keeping up with the traditional norms, values and processes. Cohabitation which was not socially ( Traditionally) accepted for unmarried couples is gaining popularity as more couples are choosing to live together either prior to or in lieu of marriage (KDHS, 2008/09).

The change with the most effects to family stability is the increase in divorce and separation. Traditionally, divorce was uncommon and was viewed as a sin or an “accident” in a marital relationship. In the African situation, what constituted a divorce was viewed against the fact that, marriage is a “process” and the process is incomplete until the entire dowry has been paid. However, temporal separations between husband and wife were common than divorce (Mbiti, 2006).

counterparts and the median age at first marriage has increased dramatically as education and wealth levels increase.

According to the KDHS (2003), in the country, marriage instability is high and marriage is on decline with couples choosing to cohabit. Divorce and separation are thus seen as acceptable for those in unhappy marriage and the social stigma attached to this is inexistent. Polygamy is declining with thirteen percent of currently married women living in polygamous unions. This is common in the rural than in urban areas and is inversely related to the education levels (KDHS, 2008/09). The traditional family norms and roles are no longer functional in the 21st century and in the modern society.

The socio-economic dynamics in the rural and urban areas have increasingly disempowered men reducing them to figureheads of households (Connell, 1995). Scholars argue that, the increase in marital instabilities is as a result of the increase in economic opportunities for women (Cherlin, 1992). In the past, women who lacked sustainable means of economic income or livelihood were trapped in bad marriages. With increase in female wage-labour opportunities, women have been increasingly able to separate or divorce and live on their own or are becoming less dependent on their husbands. Thus, the rising economic power of women has undermined patriarchal authority and destabilized marriages.

The economic view of traditional marriages has greatly changed and the frequencies of divorce and separation increased. According to Oppenheimer (1994), this has resulted from the impacts of declining economic opportunities for men. A study by Ruggles (1997) concluded that, the increasing trend of female employment in non-farm jobs is linked to the increase in separation and divorce in Most Developed Countries. In essence, the increase in individualistic value is viewed to have contributed to rising female labour participation and marital instability in the first world Countries (Gagnon and Parker, 1995).

factor to marital instability in many societies. In spite of the many initiatives that have been put in place to address domestic violence, Kenyan communities are yet to significantly reduce cases of gender violence. Studies indicate that couples in the country experience various forms of abuse by their spouses; yet many people remain in abusive relationships citing different reasons such as the children, pressure from relatives and religious values of the family (KDHS, 2003). Male dominance and women surbodination is historical and its purpose and manifestations change overtime. In Kenya, women in most communities are socialized to accept, tolerate and rationalize domestic assaults and to remain silent about such experiences (Zimmerman, 1994). According to KDHS, 2008/09, 39% of women have experienced physical assault. Violence against women in Kenya is characterized by physical, sexual or emotional assaults or threats of such acts. Currently, domestic assault constitutes the most common form of violence in Kenya with men being the main perpetrators (KDHS, 1999).

they are socially stigmatized even by their own kins (Joshi et al, 1995). They are also faced by financial crisis especially when they move back to live with their parents after separation or divorce. Most of them are partially dependent on their husbands on livelihood; moreover, women and children are more vulnerable than men to poverty after separation/divorce, and on average, they suffer significant decline in household income following separation or divorce. This increases pressure on them to engage in economic activities to maintain their families.

On the other hand, divorced/ separated women headed households are believed to be vulnerable to poverty, which is characterized by the inability of the affected women households to acquire and retain sustainable livelihoods. The effect is not as a result of climate change, population growth or environmental degradation, but due to existing socio-economic situations and lack of land an important livelihood resource in the rural areas, which is not only crucial for food production but also for settling the family. Poor/ low income households employ a number of coping and adaptive strategies to survive and thus the need to understand the driving factors of each livelihood options by separated/ divorced women in order to improve on their security to food, poverty and general wellbeing.

1.3 Statement of the Problem

equity in access; control and participation in resource distribution for improving livelihoods of women; and reviewing the national gender and development policy. Despite these goals and policies, Kenya is still faced with the problem of increase in marital instabilities and there is little information available about the causes of this trend, its effect on the family institution and the effectiveness and appropriateness of the existing policies and programmes in curbing the problem. Past studies indicate that, the incidence of separation and divorce have been increasing among women and women are three times more likely, than men, to report a divorce or instability in family, (Ayiemba;1990, KIHBS,2005/06; KDHS,1989, KDHS,1999 and KNBS,2010) The levels have increased from 2.2% ( 1989), 2.7% ( 1999) to 11% ( 2009) . Thus, this study sought to bridge this existing gap in literature by focusing on the demographic, spatial-temporal dimensions of marital instability, factors leading to the increasing marital instability, the intergenerational variations, and the effects of marital instability to the livelihoods of the affected households in Machakos County.

1.4 Research Questions

The following research questions sort to address the issues that emerge from the background of the problem:

1) What demographic and spatial-temporal dimensions/trends of marital instability are evident in Machakos County?

2) What socio-economic and intergenerational differentials and similarities exist among women experiencing marital instability in Machakos County?

4) What is the trend, hence the major causes of marital instability in Machakos County?

5) To what extent does marital instability affect women livelihoods in the County?

1.5 Objectives of the Study

The general objective of this study was to study the demographic and spatial-temporal dimensions of marital instability and its effects on family livelihoods in Machakos County, Kenya.

In order to achieve the general objectives, the following specific objectives were designed to guide the study:

1) To investigate the demographic and spatial-temporal dimensions/trends of marital instability in Machakos County.

2) To identify socio-economic and intergenerational differences and similarities among women experiencing marital instabilities in the County.

3) To examine whether those who separate or divorce, experienced physical, emotional and sexual abuse during their marriage life.

4) To evaluate the trend and the major causes of marital instability in Machakos County.

5) To investigate the effects of marital instability on women livelihoods in Machakos County.

1.6 Hypotheses of the Study

H01: There is no significant relationship between the demographic and women’s

spatial- temporal dimensions/trends and family instability in Machakos County. H02: There is no significant difference between women’s socio-economic

backgrounds and marital instability through separation or divorce.

H03: Separated or Divorced women of Machakos County do not experience physical, sexual or emotional abuse during marriage life.

H04: There is no significant difference between the pattern of marital instability

among women of different age cohorts and the causal factor(s).

H05: There is no significant difference between marital instability and women livelihood options in Machakos County.

1.7 Justification of the Study

Research on marital instability in Kenya is virtually lacking. The existing research by KDHS, (1998, 2002), KNBS, (2010), and KIHBS (2005/06) revealed that marital instabilities are increasingly becoming common. However, important issues such as the factors associated with this trend and their effects to the family livelihoods were left out. This study thus uncovers the existing real scenarios leading to marital instabilities. It also advances literature on the topic in demography/population geography, economics, anthropology, gender and sociological studies.

which could affect marital stability. Thus this study involved four generational cohorts, aiming at studying the intergenerational differences and similarities on the factors leading to marital instability. It is important to have a comprehensive understanding on the factors associated with this phenomenon with a view of coming up with appropriate interventions to address the need of couples who may be at risk of experiencing marital instabilities. This is because, female-headed households are prone to poverty and are likely to head impoverished families ( Machakos District Strategic Plan (MDSP), 2008-2012). Thus, the vulnerability of the affected female- households to poverty has threatened existence of a family as a social structure.

Family is an integral part of development process in a country. However, marital instabilities bring changes in family structure which may have impact on human capital development in the affected region/country. Thus, necessary concerns should be taken into account on research on the topic to have an updated detailed statistics on changing socio-economic aspects of this vulnerable group and for the wellbeing of this pivotal social institution, in order to promote successful parenthood after marital instability and maintain human capital necessary for economic development in the county and the country in general.

In Kenya, the few existing demographic research work has focused on marriage/nuptiality and especially on determinants of nuptiality (Njenga,1979; Barasa,1993; Dilnesahu,1999 ), marriage and religion (James,1989), estimation of nuptiality levels (Mabel,1985; Aganda, 1989); determinants of age at first marriage (Makheti, 2008); Marriage and first birth (Mulwa,2009); and socializing women into marital responsibility (Naomi,2013) and extended family conflicts and social capital dynamics (Mkok,2012). It is only Omondi (1989), who did research on demographic analysis of marital dissolution in Kenya. Most of these studies were based on longitudinal or secondary data from census reports. This study however, used cross-sectional empirical data to explore the real life scenario of the phenomenon in the region.

1.8 Scope and Limitations

This study focused on the determinants of marital instability and its effects on the livelihoods of the affected women. Despite of its significance, this study had some limitations. The data collection were restricted to only three districts in Machakos County, thus the sample may not have been wholly representative since people experiences and response may vary because of regional differences in terms of resources and neighbourhood environment. However, the study assumed that since the sample was subjected to similar socio-economic aspects and almost similar environment, the results findings can be generalized to all the affected women based on this aspect.

During the interviewing process, the researcher faced problems in explaining the question regarding monthly household income. It was hard to justify how households’ income can be measured effectively because it was hard for the women to account since the income varied depending on the available job or the nature of business done during different period/season of the year. The question on household income might have been affected because of false expectations of assistance by respondents, despite a repeated explanation regarding the purpose of the study. There might have been under-reporting of income by some of the respondents. However, each respondent was asked to explain the nature of jobs done by the couple on monthly basis for the last four months and the wage paid. An average amount of wage for both the husband and the wife was computed and indicated as their household income. The question on husband’s monthly income was dropped because most of the women never had an idea of how much their husbands earned for those who had husbands employed in public or private sector. In other instances, the women could not provide estimates of their husband’s monthly income due to the fact that their jobs were seasonal.

1.9 Operational Definitions of Key Terms

In this study, a number of terms and concepts have been used and their operational definitions in this study are necessary. These are:

Population: Is the group to which a researcher would like the results of a study to be generalizable. It has a unique characteristic that differentiates it from other groups. In this study, population referred to the separated, divorced or deserted women aged between 15 years and 49 years in Machakos County.

Marriage: Is a legal, social and religious union between two adult’s individuals that unites their lives legally, gives legitimacy to sexual relationship and reproduction for legitimate children. The legality of the union may be established by civil, religious or other means as recognized by the laws of each Country or area.

Marriage Rate: The number of marriages in a given year per 1,000 people in the population.

Remarriage: Is a legal and social arrangement between two persons, one of which has previously been married.

indicated by separation, desertion or divorce. Thus it excludes family instabilities as a result of death of a spouse. Separation/ divorce are also examined to establish whether they lead to family instabilities in the County after marriage breakdown.

Marginalized: Are a group or a class of people who are accorded lesser importance such that issues affecting them are not well taken care of. It is mostly a social phenomenon by which a minority or sub-group is excluded and their needs, desires and expectations, almost ignored by the Government and the society concerned. In this study, the separated, divorced or deserted women were referred to as the marginalized.

Desertion: Is the failure to make adequate provision for the maintenance of a spouse and or children by separation from the family unit.

refers to a marriage which is legally dissolved and the parties given the rights to remarry under civil, religious and or other provisions according to the laws of each country.

Divorce Rate: Is the number of divorce cases per 1000 married women in a Country.

Family/Household: A family is a group of persons who live in a common household and are related to specific degree by birth, marriage or adoption. At times household is taken to be synonymous with family. In third world Countries, household is commonly used than family. A household can have more than one family living together; it may also have only one person while a family must have at least two members.

Household Head: Is the most responsible man or woman in a household who makes key decisions in the household on a day-to-day basis and his/her authority is respected and honored by all members of the household.

Vulnerability: Is the degree to which a person is exposed or susceptible to or unable to cope with family changes. In this study, it refers to the high degree of exposure to risk and stress of marital instability and proneness to poverty when livelihood is unsustainable or insecure.

Livelihood: Are ways/ means of gaining living. It comprises people, their capabilities, assets (including both material and social resources) and activities required for a means of living.

Livelihood Strategies: Are the combination of activities that people choose to undertake in order to achieve their livelihood goals. Sustainable Livelihood: This is the ability of the means of gaining living of the

( a key livelihood resource in the rural areas), and their level of satisfaction with their current living standards.

Woman: The concept, woman, in this study is associated with the ladies who are victims of marital instability due to separation, desertion or divorce by their husbands.

Marital Violence: Is violence perpetrated by partners in a marital union.

Gender-Based Violence: Is any physical, sexual or psychological assaults that occurs within the family. This study only covers domestic violence that occurs within the household.

Age Cohort: Signifies a group of people born in a specified time period. Age cohorts of <24, 25-34, 35-44 and 45-49 years were used in this study to measure the intergenerational trend of marital instability.

due to the exposure to similar education, communication, transportation and economic production (Dekerseredy et al., 2004; Fisher, 1995). Moreover, rural areas have greatly been influenced by external, cultural, economic and social forces depending on their proximity to cities (Donnermeryer et al ,2006).

Urban: Refers to towns and cities whose main activities include: trade, commerce, industry, among others; and has a population of 2000 and above. In this study, definition of urban areas includes Cities, Municipalities, Town Councils and Urban Councils.

Unemployed: In this study, unemployed person is anyone who does not have any source of income in form of salaries, wage or from any family asset (Livestock or crop farming).

Resilience: Is the ability of the household to maintain a certain level of wellbeing to make a living and its ability to handle risks depending on those households’ available options.

1.10 Ethical Consideration

This study followed the official procedure for research with human subjects. When cases for the study were identified, they were informed that participation in the study was voluntary. Before the voluntary respondents were interviewed, a clear explanation of the study’s purpose and objectives was done. The anonymity of the participants was also guaranteed before their consent was sought at the start of the individual interview. Questioning was implemented only when privacy was obtained to provide assurance to the voluntary respondent that no one-else could know about the nature/type of questions the respondent was asked. No financial gifts/incentives were offered to the participants and they were also informed that their participation was to be key contribution to their future welfare and policy intervention.

1.11 Summary

CHAPTER TWO

LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1 Introduction

This chapter explores a wide range of literature on specific factors focusing mainly on marital instability that is: Demographic factors and spatial-temporal factors, family background, socio-economic issues, interpersonal relationship behaviour and women perceptions based on attitudes and beliefs towards separation/ divorce. Understanding the spatial-temporal dimensions of how these factors are differently associated with marital instability, provides a better understanding of why some marriages breakdown and others remain intact. Literature was reviewed in this chapter together with theories associated with marital dissolution to gain insights of this phenomenon. Based on the theories and the literature, a conceptual framework was developed to show the interrelationships between the different factors associated with the risk of marital instability and how they may contribute to livelihood options for the affected families.

2.2 Empirical Studies

2.2.1 Demographic Factors

2.2.1.1 Age at First Marriage

Studies in Most Developed Countries have found age at first marriage to be a major predictor of marital instability (Karney and Bradbury, 1995). In Australia, it has been revealed that, young age in marriage increases the likelihood of marital separation/ divorce especially to those who marry under age of 25 years (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2000). According to Becker( 1991); Hoem and Hoem,1992; South, 1995; Kalmijn and Poortman (2006), those who marry while young rush into marriage and in the process they make poor mate selection. According to Booth and Edwards (1985), this is attributed to lack of role models, failure of the couples to seek approval from family members and friends. Others scholars argue that, such marriages face greater risk because the couples are less likely to have developed the maturity and social skills required to negotiate a long term marital relationship and often do not have access to adequate socio-economic and financial resources (Wolcott and Hughes,1999). Age difference is associated with separation/ divorce especially in cases where the husband is more than three years more older than the wife (Tzeng,1992). It is also argued that individuals marrying at a young age may be less compatible with one another, less prepared for marriage, and lack economic resources( Oppenheimer, 1994;Booth and Edward,1985).

socio-economic changes in the society. In United States, since the 1950’s the median age at first marriage has risen for both men and women , increasing from 23 for men and 20 for women in 1950 to 28 for men and 26 for women in 2009 (US Household Economic Studies,2009).This is attributed to changing male and female opportunities, the growth of cohabitation and an emerging view of formal marriage as a transition to be postponed until financial security has been attained (Cherlin,2004).

In England and Wales, divorce registration data indicate that, among the women who married in 1984, 35% of those who married while young divorced within ten years compared to 22% of those who married in their early twenties and 15% of those who married later (Haskey,1996). In the year 2011, The report also indicated that, at young ages there were more women than men separating/divorcing while at older ages, more men than women divorced. This pattern reflects the differences seen in age at marriage of men and women. The mean age for men marrying in 2010 was 36.2 years compared with 33.6 for women. In 2011, the number of divorces was highest among men and women aged 40 to 44(National statistics, 2012). About 8% of males divorcing and 5% of females divorcing were aged 60 years and over. Women in their twenties had the highest divorce rates of all female age groups with 23.9 females divorcing per thousand married women aged 25 to 29 in 2011.The median age at first marriage was 25.8% for women and 28.3% for men (Casey at el, 2012).

Namibia, the age at first marriage is rising (Harwood, 2001). According to United Nations (2009), age at marriage is earliest in Savannah West Africa and in Eastern Zaire and Eastern Angola and those who married before 20 years are mostly found in Chad (86%) and Niger(85%). This is attributed to low level of female education and small per capita incomes.

Other countries where at least 75% of women in this cohort were married before age 20 are Bangladesh and Burkina Faso, Guinea, Mali, Mozambique, Nepal and Uganda. Countries with the lowest proportion of women married as teenagers are Namibia and South Africa at 20 and 14%, respectively (Charles , 2003). According to UN (2009) the oldest median age at marriage for men 30-34 is 30 years in Senegal and the youngest is 22.3 years in Uganda. In Kenya, about 10% of men marry before their 20th birthday and nearly half marry before age 25 (KDHS, 2010).The median age at marriage among men aged 30 and above is 25.1 years and has remained unchanged since 2003. According to KNBS, (2010), half of all women enter marriage before their 20th birth day and the median age at first marriage for women aged 25-49 is 20 years, which indicates a slight increase when compared with the median of 19.7 years in 2003. Generally, all these studies show variations in age at marriage in different regions; however most of the mean ages at marriage for the separated/divorced are not computed as per the age structure of marriage. The age at marriage for different marriage cohorts is assumed to be the same and the results do not show variations in separate or divorce in the different age cohorts. This study aimed at showing the separation/divorce rates for women married at different ages.

2.2.1.2 Number of Children

A family study in Denmark found that, children do not increase marital stability but rather raises the probability of separation/divorce (Svayer and verner, 2008). Contrary to these findings, research in Britain by Berrington and Diamond, (1997); in Canada by Hall and Zhao, (1995) and in United States by Lillard et al, (1995) revealed that, separation/divorce is more common among childless couples. The analysis of Swedish Fertility Survey (Trussell et al.1992) found the opposite. This could be explained by the fact that, childbearing couples are likely to stay together for the "sake of the children" or that couples who are unsure about their marriage may put off childbearing (Becker et al., 1977). Previous studies in Britain (Murphy,1985), Sweden (Anderson, 1997) and United States (Becker et al., 1977) found a different trend that, couples with more than three children are likely to separate/ divorce than those with fewer children.

2.2.1.3 Age of Children

Research findings in Australia by Bracher et al.,(1993), suggest that, the age of children within the marriage can independently have effects on the risk of separation/divorce.This results concur with study findings in France by Toulemon (1994); in Sweden by Anderson(1997); and in United States by Becker t al.,( 1977). This suggests that, younger children have a stabilizing influence in a marriage. According to Waite et al. (1985) research findings from United States, a first birth significantly decreases the risk of marital instability for the subsequent two years. The age of the children in a marriage may not independently influence marital instability because childbearing is part of marriage life and therefore this study looked at the association of children age and other intervening factors on marital instabilities.

2.2.1.4 Premarital/Marital Birth

non-marital births who were married before 1976 (Murphy, 1985). Children born within marriage reduces the likelihood of divorce (Bracher et al., 1993; Ono, 1998), this is because the birth of children within marriage increases commitment to the marriage and increases its stability (De Maris and Rao, 1992; Sayer and Bianchi, 2000). However, this depends on the gender of the child (Morgan et al., 1988). A study by Devine and Forehand ( 1996) found that, parents of girls are more likely to divorce than parents of boys. This findings reflect the existing traditional preference for sons in a marriage than girls which was also tested in this study.

2.2.1.5Remarriage

2.2.2 Spatial-Temporal Factors 2.2.2.1 Marriage Duration

The risk of divorce is expected to decrease with an increase in marriage duration (Thornton and Rodgers, 1987). The risk of divorce theorized to increase during the first three years of marriage, and over one-third of divorces occur within the first five years (National Centre For Health Statistics, 1991). According to the European Statistics Year Book (2009), the mean duration of each marriage exceeds 10 years in every member state, rising to nearly 17 years in Italy. In Spain, marriages last for 13.8 years; 12.9 years in Netherlands, 10.4 years in Germany, 9.4 years in Austria and 10.9 in United Kingdom and Hungary. According to Becker (1991), early separation/divorces in marriage are as a result of changes in ones perception about the other partner especially after gathering negative information about the spouse after marriage. On the other hand, separation/divorce later in marriage arises due to changes in partners character like being promiscuous and/or other life events such as growing apart and lack of family cohensiveness that affects the couple relationship (Amato and Previti,2003), whereas those in short-term marriages cited personality differences and basic incompatibility. These studies show the average marriage duration in the stated countries without showing the variations across age groups which has been looked into in this study. The current study also looked into the factors influencing marriage duration.

2.2.2.2 Living Arrangements

Britain by Kiernan, (1986), and in United States by South, (1995). Studies in Britain between 1960’s to 1970’s found that those who married and started marriage life in rented houses as opposed to the owner occupier experienced an increase in divorce risk by two thirds with those starting life in local authority housing having intermediate risks( Bracher et al. ,1993). It is likely that place of residence may contribute to marital instabilities probably due to financial aspects. However, in the rural areas land is available and most of the couples at least have a rural home. Therefore in this study, living arrangement was tested on the basis of whether the couple was living in urban center, in the peri-urban, or in the rural home and how the stated place of residence affected their marriage leading to marital instability. The study also looked into the place of resident after separation or divorce as a way of establishing their livelihoods because land is an important livelihood asset in the rural areas.

2.2.2.3 Premarital Cohabitation

States (Axinn and Thornton,1992; Lillard, et al.,1995) indicate that couples who cohabit prior to marriage have a higher risk of marital instability. The actual risk varies between different studies. Kiernan (2002) found that, indirect marriages did not pose any greater risk of marital dissolution than direct marriages in Sweden, Norway, Finland and Austria, but in France, Switzerland and Germany, indirect marriage was associated with greater instability .

Couples who live together before marriage are believed to have been in a relationship longer than those who do not cohabit, thus they have longer exposure to the risk of relationship instability which explains in part the higher rates of instabilities evident for marriages preceded by cohabitation. In United States, the percentage of women who were cohabiting rose from 3.0% in 1982 to 11% in 2006-2010. It was higher in some groups, including Hispanic groups, and the less educated. Among the women, 68% of unions formed in 1997-2001 began as cohabitation rather as marriage (Casey et al, 2012). The extend of differences found between union types varies depending on the cultural background. In a study of European countries, Hamplova (2009) found that cohabitation became more common in a particular society, marriage and cohabitation become more similar in terms of their characteristics. Given the place of cohabitation in contemporary union formation, it is important not to assume that the role of premarital cohabitation is the same in all countries. In regions where premarital cohabitation is less accepted or has not become normative, contemporary cohabitation may still be associated with enhanced risk of subsequent marital instability. Thus this study aimed at establishing the associations between premarital cohabitation, marital instabilities and other associated factors since those who cohabit have other demographic, spatial-temporal and socio-economic characteristics which put them at a higher risk of marital breakdown. These factors may be partly responsible for the different patterns.

2.2.3 Family Background

2.2.3.1 Parents Socio-Economic Status

Several studies have emphasized the effects of family structure in perpetuation of family instability across generations (Carson and England, 2011; Murphy, 2013; Liefbroer and Elzinga, 2012). Fasang and Raab (2014) showed that, other than strong intergenerational transmission, other systematic patterns exist between parental and filial formation. Family socio-economic background is hypothesized to influence marriage instability in two ways. First, people from more prosperous and educated family backgrounds may have more stable marital histories because; they have been exposed to less hardships and turmoil while growing up (Wolfinger, 1999).

instability since several studies have found a strong positive association (Lyngstad, 2006).

2.2.3.2 Parental Separation

It has been theorize that, changes in the family structure, especially parental separation, can have negative impacts on a child’s future development (Amato and Anthony, 2014). It is also argued that, couples whose parents have divorced are more prone to divorce. Evidence from the United States and Britain suggest that the risk of divorce is higher among those who experience the instabilities of their parent’s marriage. This phenomenon has been labeled the intergenerational transmission of divorce risk (Amato, 1996; Kiernan, 1997; Beck-Gernsheim, 2002).

Studies in United States by Amato (1996), based on longitudinal data found that, intergenerational transmission of divorce was as a result of increased likelihood of children from broken families to exhibit behaviours that interfere with the maintenance of mutually rewarding intimate relationships. It was further found that, parental divorce is associated with an increase in problems among offspring’s due to jealous, promiscuity, bad habits, misuse of money and drinking/drug abuse (Pope and Mueller, 1976; Glenn and Kramer, 1987; Bumpass et al. 1991; Berrington and Diamond, 2000; Kiernan, 1997). Similar studies In Australian by Burns and Dunlop (2000), examined effects of personal qualities of children of divorced parents reported by parents and the children themselves to the quality of their early adult relationships. The results suggested that children from broken families had more behavioural problems than children of intact families, which in turn negatively affect the quality of their intimate relationships 10 years later.

indicate that, low parental contral/supervision leads to early entry into marriage of children from broken families, mostly as a result of premarital conception. The research findings also suggest that, children from broken families lack successful role models on marital interaction and communication. As a result the children may find marriage less attractive, and their ability to deal with marital stress may be jeopardized (Pope and Mueller, 1976; McLanahan and Bumpass, 1988; Amato, 1996).

Generally, experience of parental divorce may lower commitment to marriage (Glenn and Kramer, 1987), and encourage more liberal attitudes to marital instability, thus providing lower barriers to dissolution (Amato, 1996; Axinn and Thornton, 1996).Children who have experienced parental separation/divorce have been shown to be more likely to separate (Lyngstad and Jalovaara, 2010), since the risk of union breakdown depends on the prevalent union behaviour within specific setting (Reinhold, 2010). Although there may be some relationship between parents and their children separation/divorce, this study went deeper and examined whether children have a higher probability to experience the same family formation pattern or whether there are other intervening factors because parental divorce is very different experience even for children in the same family. Moreover, the children also have different life experiences that they do not share.

2.2.4 Respondent’s Socio-Economic Factors

socio-economic characteristics will affect the risk of dissolution directly and indirectly through their impact on marital factors. For example, level of education may affect the risk of dissolution through its effect on attitudes towards traditional family norms, but will be associated indirectly with divorce through the relationship between lower levels of education and young age at marriage.

2.2.4.1 Education

Most of the studies in the United States have suggested that the risk of divorce is significantly higher among those with lower levels of education (Teachman and Polonko, 1990; Greenstein, 1995; South, 1995).Studies in China (Hymowitz,2006) found education to be positively related to marital stability with high education related to lower likelihood of divorce or separation. In Canada and Australia, studies found little difference in the risk of marital instability and educational attainment (Bracher et al., 1993; Balakrishnan et al., 1987).

divorce are lower if the husband is in a higher educational category than his wife; than they are among couple of the same educational status (Bumpass et al., 1991; Heaton, 2002) and are highest if the wife is in a higher educational category than her husband.

In regards to subjective accounts, individuals with higher levels of education are more likely to cite incompatibility as the cause of divorce (Amato and Priviti, 2003).Studies by Blossfeld et al. (1993) in Italy which have more traditional family settings found that, educated women have more liberal views on marriage and divorce and are able to cope with the socio-economic consequences of divorce. In general, although most of the results findings to these studies are inconsistent, they commonly looked at education on its own as a determining factor to marital instabilities. In this study, education tends to serve as a link to other demographic, spatial-temporal, socio-economic and family background variables which are hypothesized to lead to marital instability. It has also been used to establish whether it’s a contributing factor to livelihood options before or after marital instability.

2.2.4.2 Economic Circumstances

highly associated to risk of separation/divorce; and that, divorce was greater when wives contributed about half of the total family income.

Research in other American regions found no relationship between the husband’s income and risk of divorce (Greenstein, 1995; Amato, 1996). In terms of employment, rates of divorce are elevated among couples in which the husband or both husband and wife are unemployed during the first year of marriage (Bumpass et al., 1991; Tzeng, 1992). Studies in Australia suggest that, the husbands unemployment influences marital dissolution (Bracher et al., 1993), while in Britain unemployment has been found to have a complex associations with an increased risk of marital instability.

2.2.4.3 Women’s Employment in Paid Work

whether the role of part-time or full-time jobs as a way of livelihood can led to marital instabilities in families.

2.2.4.4 Religiosity

Research in Britain (Murphy, 1985; Haskey, 1987) revealed higher levels of marital instability in marriages legalized in civil courts as opposed to religious ceremonies. Many Australian religious groups view marriage as sacred bond and emphasizes on remaining married thus reducing the likelihood of marriage instability to the believers (Waite and Lehrer, 2003). Studies in Australia (Bracher et al, 1993); Britain (Berrington and Diamond, 1997), United States (Bumpass et al., 1991) and Canada (Balakrishnan et al., 1987) found that religiosity is less associated with marital instability because people who have higher levels of religiosity, have a strong negative association with marital instability (Rogers and Amato, 2000) . Low religious participation is associated with a greater risk of marital instability (Heaton, 2002). According to Amato and Priviti, (2003), more religious individuals were more likely to cite infidelity as a cause of divorce and less likely to blame incompatibility. They stressed that this does not indicate that, religious individuals are more likely to experience infidelity; rather, it may demonstrate that highly religious individuals divorce only under extreme conditions. This study tested respondent religion affiliation, and how religion has influenced decision making on separation/ divorce across the age cohorts.

2.2.4.5 Previous Experience of Partnership Dissolution

experienced partnership dissolution prio to their first marriage. The rates were also high among couples where one or both partners were previously married( Harskey,1996). This indicates a lack of knowledge/skill in suitable partner selection or in staying married( Bracher et al ,1993). To Levinger (1976), divorced persons view separation/divorce as a better solution to marital conflicts and thus more acceptable. Besides, separation/divorce risk increases when conmbined with other characteristics such as cohabitation prio to marriage, non-marital births and more contemporary attitudes towards marriage and separation/divorce(Berrington and Diamond, 1997).

2.2.5 Attitudes to Divorce

2.3 Marital Instability Levels Worldwide

Divorce and separation rates have been increasing throughout the world, a pattern that have been uneven, occurring at different times in different countries. In the western societies, these changes are attributed to: changes in gender roles and increase in married women’s labour market activities (Kalmjin, 2007; Cherlin, 2009), declining economic fortunes for men in these countries (Ozean and Been, 2012); dynamic cultural and family attitudes towards gender equality (Cherlin, 2009). Religiosity, secularization (Kalmjin, 2010), inter marriages which resulted to cultural differences among the couple (Dribe and Lundh, 2012) and liberalization of divorce laws (Legal reforms) in most of the western countries especially, Sweden (1974), Italy (1981), Ireland (1997), Mata (2011), among others (Gonzalez and Viitanen, 2009), also contributed much to these changes. The other factors included, increase in levels of literacy/education, income, out of wedlock cohabitation (Lyngstand and Jalovaara, 2010) and increase in international migration where migrant groups landed in societies where marriage and divorce rates differ from those of their homeland countries (Charsley and Shaw, 2012; Lyngstand and Jalovaara, 2010).

According to Goldstein (1999), this leveling was as a result of the following: The aging of the baby boomers which increased the average duration of intact marriages, the increase in age at first marriages which has lessened the number of young brides and grooms; a possible end to the rise in remarriages which historically have had higher dissolution rates and the increase in cohabitation which may have siphoned away some of the couples most likely to divorce. According to the European Statistics Year Book (2009), the average number of divorces in EU-27 member states grew rapidly and exceeded one million a year in 2005, which corresponds to 42 divorces per 100 marriages. Countries like Denmark, Belgium and Germany, have high divorce rates with rising levels; while others like Hungary, Sweden, Luxembourg, Hungary, Austria, and Finland have considerably high divorce rates that have remained relatively constant over time (Stevenson and Wolfers,2007). Studies show, separation or divorce rates are below 40% in the EU and 50% in the US (Eurostat,2007; Cherlin,2005). Although the real cause of this trend is not well known, this trend is largely associated with increase in women labour force participation (Stevenson and Wolfers,2007).

level with Central and Northern Europe states (Lee, 2006). Divorce laws in Spain changed in 2005 when new socialist government came up with express divorce law. The divorce rates increased in 2004 from 127,000 in 2007 before declining to 100,000 per year by the end of the decade. Low levels were found in Eastward Ex-communist countries especially, Bulgaria, Romania, Slovenia and Poland (Goode, 1993). In Russia, divorce was low in early 1960’s (< 2 per 1000 population, (Figure. 2.3), but later doubled in a period of fifteen years and remained high up to date (Adveev and Monnier, 2000). China had low divorce rates in the 1960’s and 1970’s during the chaotic Cultural Revolution era (Zeng and Wu, 2000). The freeing up of divorce regulation in 2001 and 2003 led to a sharp increase in the rates between 2000 and 2005 periods (Lee, 2006).

Table 2.1: General Divorce Rates (Number of Divorce per 1000 Population Aged 15+), in Various Countries and Regions, 1980-2005.

Countries Years

OECDCountries 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 2005

Australia 3.6 3.3 3.2 3.5 3.3 3.2

France 2.0 2.5 2.3 2.5 2.4 3.1

Germany 1.9 2.5 2.0 2.5 2.8 2.8

United kingdom 3.8 4.0 3.6 3.6 3.2 3.4

United states 6.7 6.3 5.9 5.6 n.a n.a

Russian federation 4.7 4.5 4.9 5.7 5.2 4.9

Asian countries

Hong Kong n.a 1.0 1.2 1.9 2.42 2.5

Japan 1.6 1.8 1.6 1.9 3.2 2.4

South Korea 0.9 1.3 1.3 1.6 1.3 3.3

China n.a n.a 1.0 1.3 1.3 1.7

Thailand 0.8 0.9 1.2 1.3 n.a n.a

Singapore 1.0 1.0 1.6 1.5 1.3 1.9

Iran 1.1 1.5 1.2 1.0 1.2 1.7

Syria 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 0.7 1.4

Turkey 0.6 0.6 0.7 0.7 2.9 1.8

Jordan 2.4 2.6 2.9 2.5 1.6 2.9

Bahrain 3.0 1.6 1.8 1.7 2.0

Other Muslim Countries

Egypt 2.7 2.8 2.3 1.8 1.6 1.3

Libya 2.2 n.a 1.1 0.4 0.4 0.5

Tunisia 1.9 1.4 2.4 1.3 1.4 n.a

Source: Gavin w, (2010)